Machine Learning Model Based on Multiparametric MRI for Distinguishing HER2 Expression Level in Breast Cancer

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

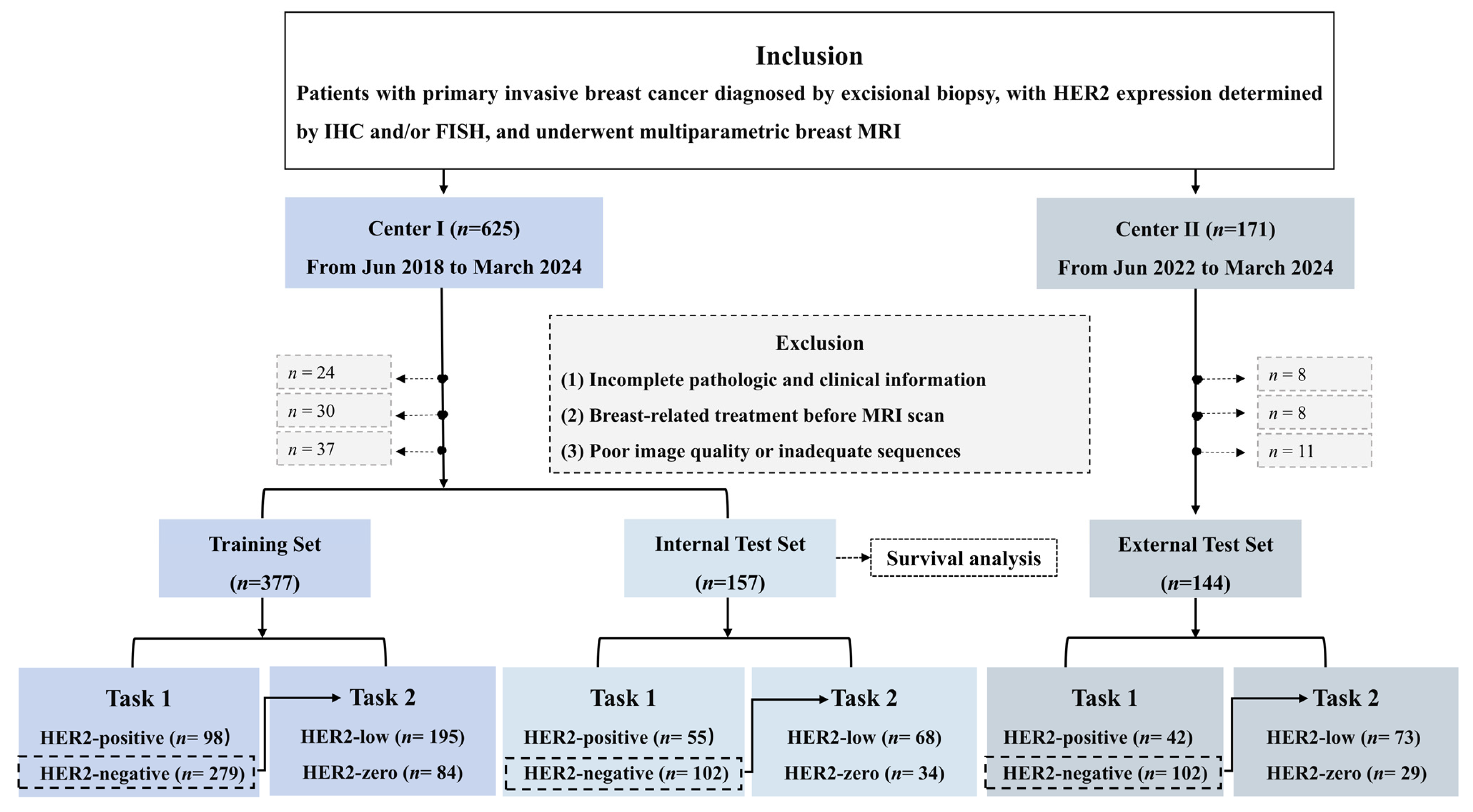

2.1. Study Sample

2.2. Clinicopathologic Data Collection

2.3. Breast MRI Acquisition

2.4. Conventional MRI Features Assessment

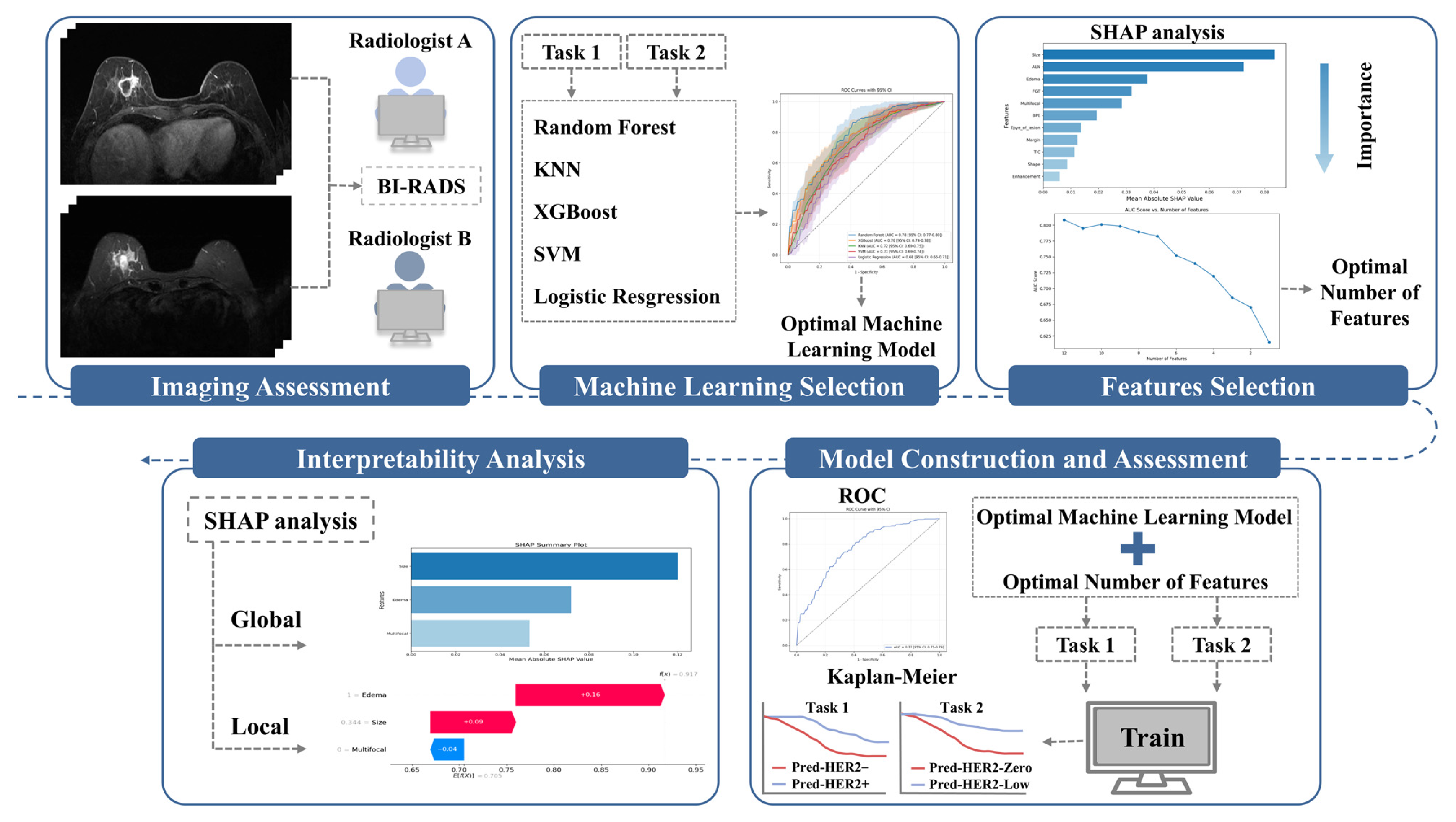

2.5. Model Construction and Evaluation

- Step 1: Five ML models were selected, including RF, support vector machine (SVM), extreme gradient boosting (XGBoost), K-nearest neighbors (K-NN), and logistic regression (LR). Before model construction, continuous variables were standardized. To mitigate class imbalance, SMOTE (Synthetic Minority Over-sampling Technique) was applied to the training data by generating synthetic samples for the minority class. Hyperparameters were optimized using a combination of grid search and manual fine-tuning. Each model was validated using 10-fold cross-validation, and the model with the highest mean AUC was selected for the next step.

- Step 2: Feature selection was based on the contribution of each feature in the selected ML model, ranking them by importance [24]. Features were progressively removed in ascending order of importance, with the AUC recalculated at each step. The process was halted when the AUC reduction became statistically significant compared to the model with all features, as determined by the DeLong test [24]. The number of features at this point was finalized for the model, balancing predictive performance and feature reduction.

- Step 3: Using the selected features from Step 2, the final ML model was developed and validated through 10-fold cross-validation. Performance was evaluated using several commonly applied metrics, including the area under the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve, accuracy (ACC), specificity (SPE), sensitivity (SEN), positive predictive value (PPV), and negative predictive value (NPV).

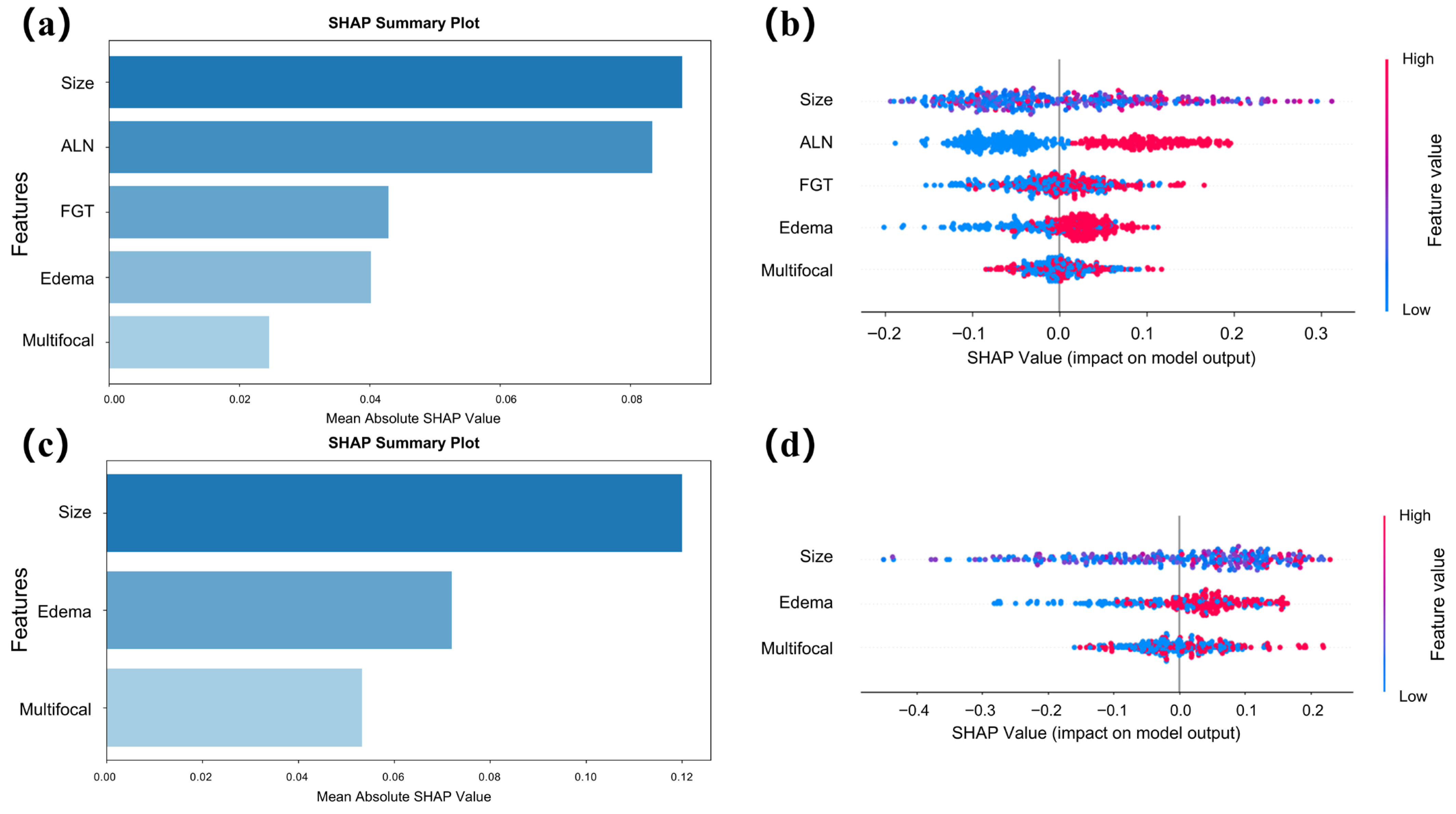

2.6. SHAP-Based Interpretability Analysis

2.7. Survival Analysis

2.8. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Patients

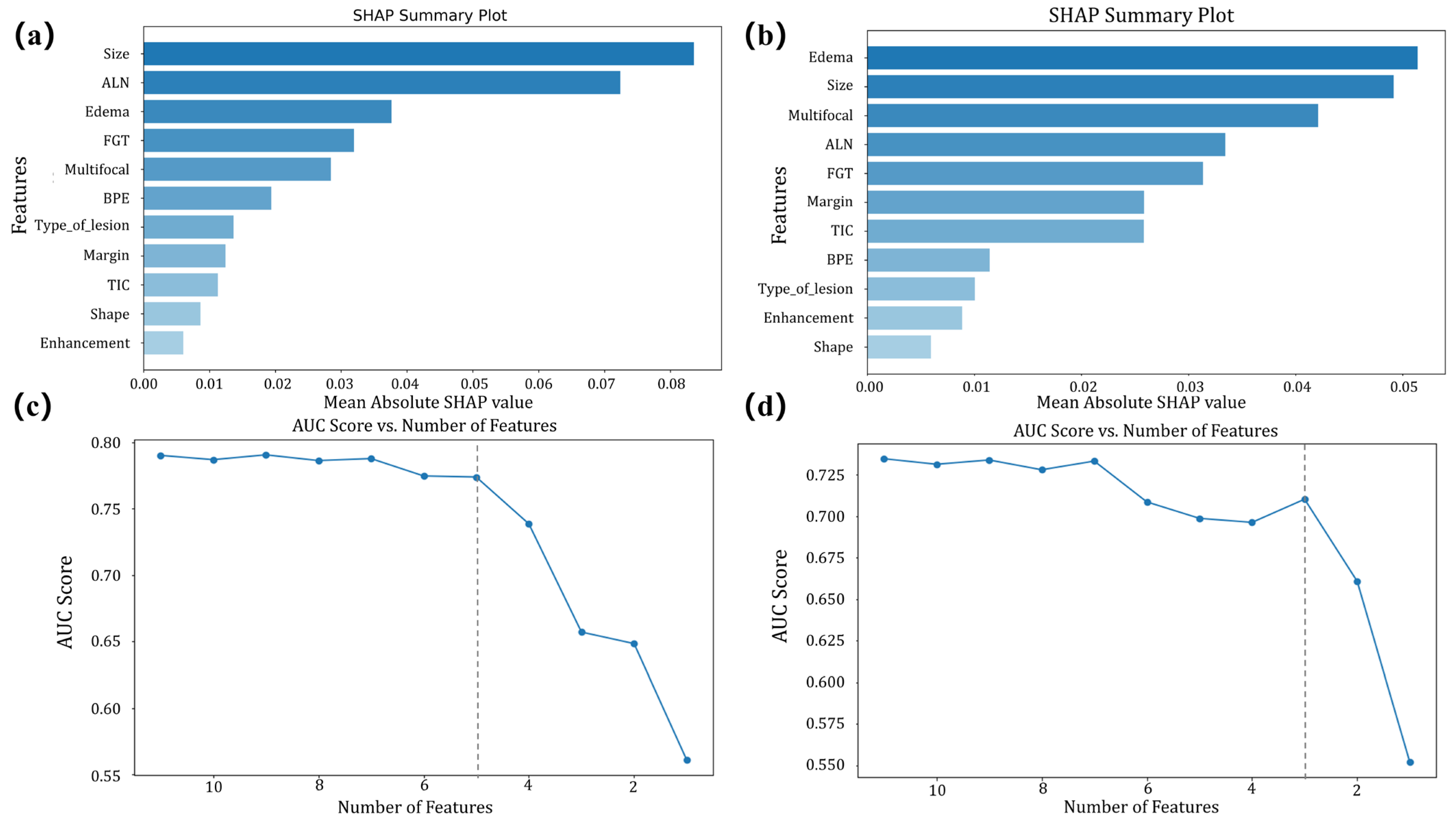

3.2. Model Construction

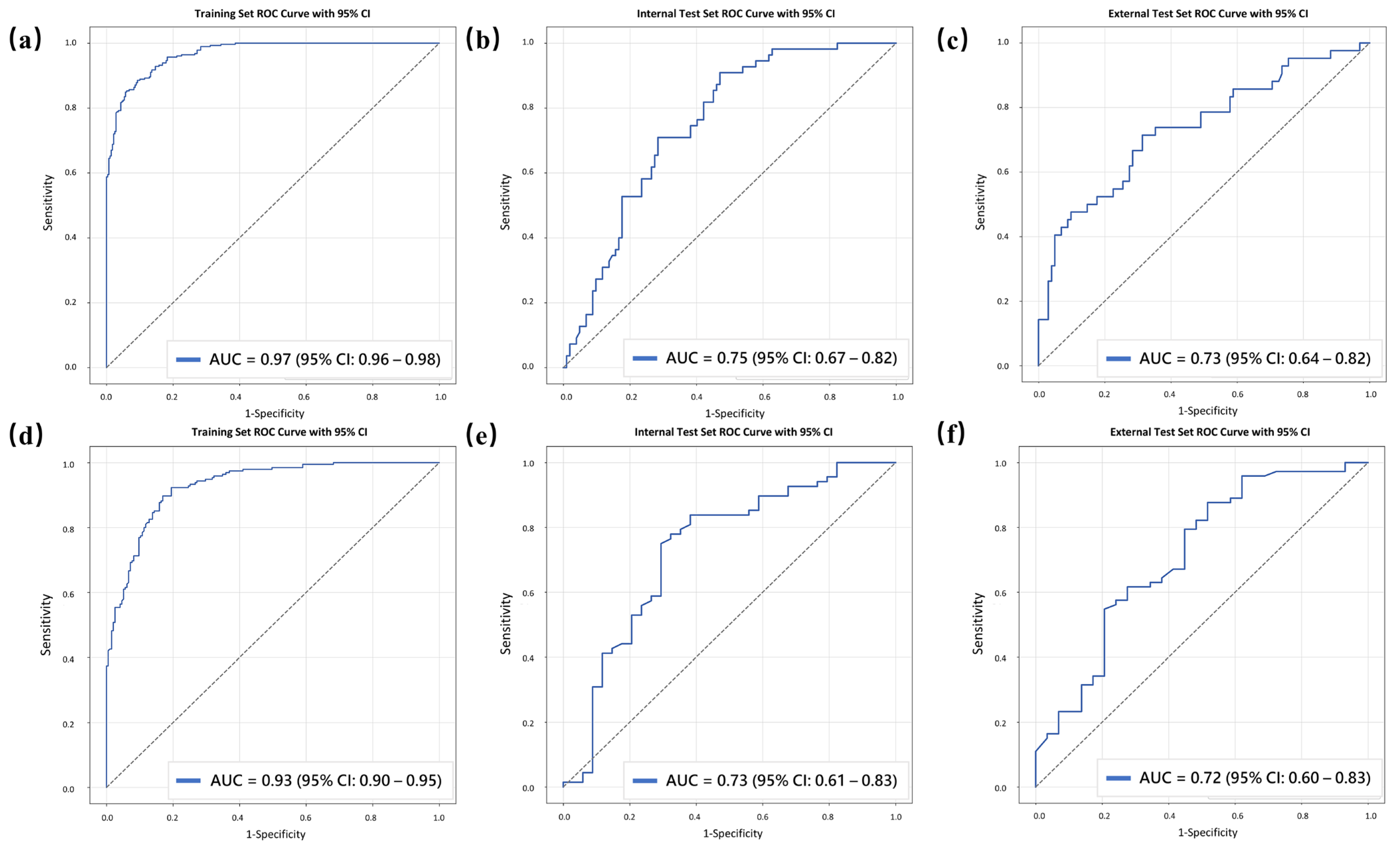

3.3. Model Performance

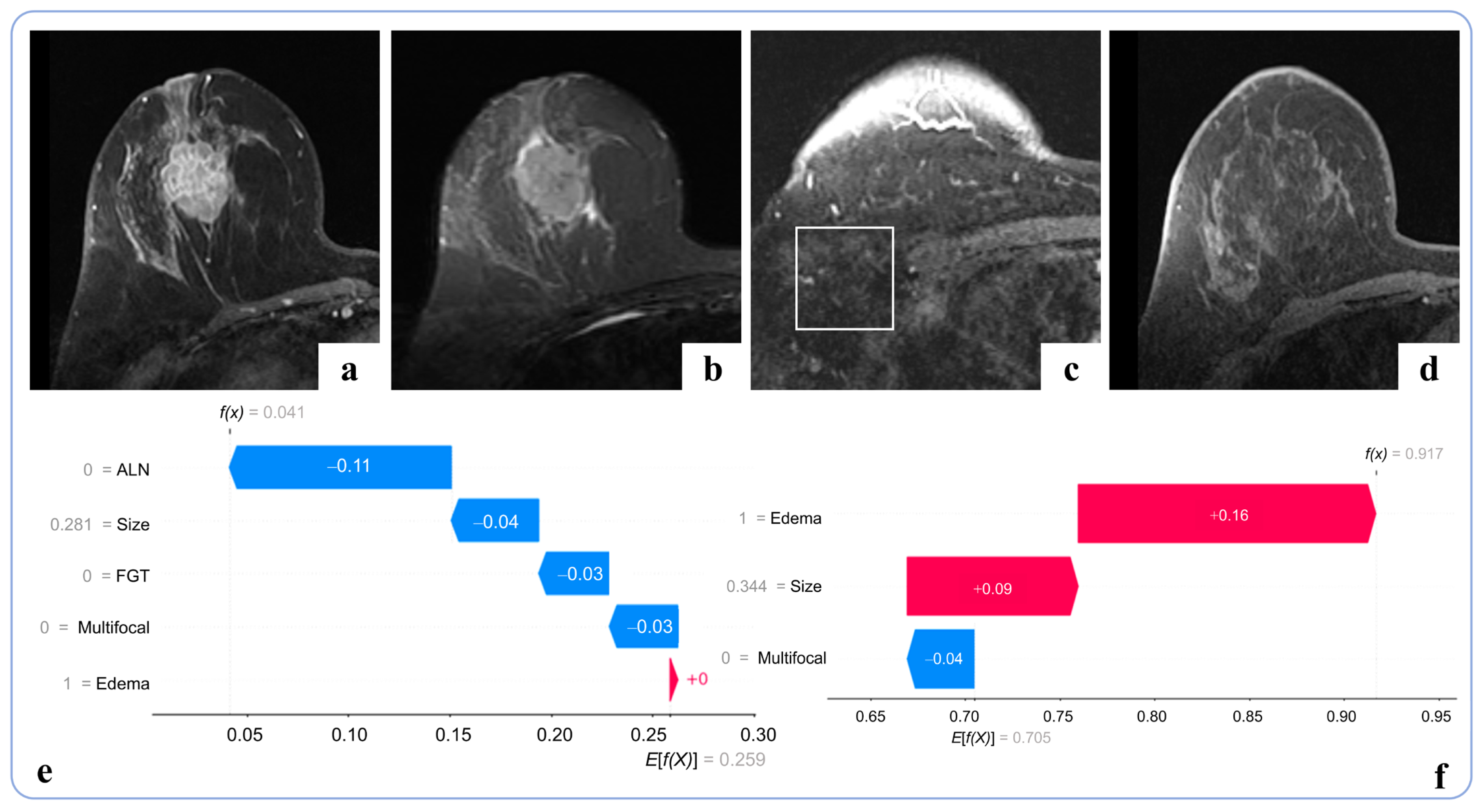

3.4. Interpretability Analysis

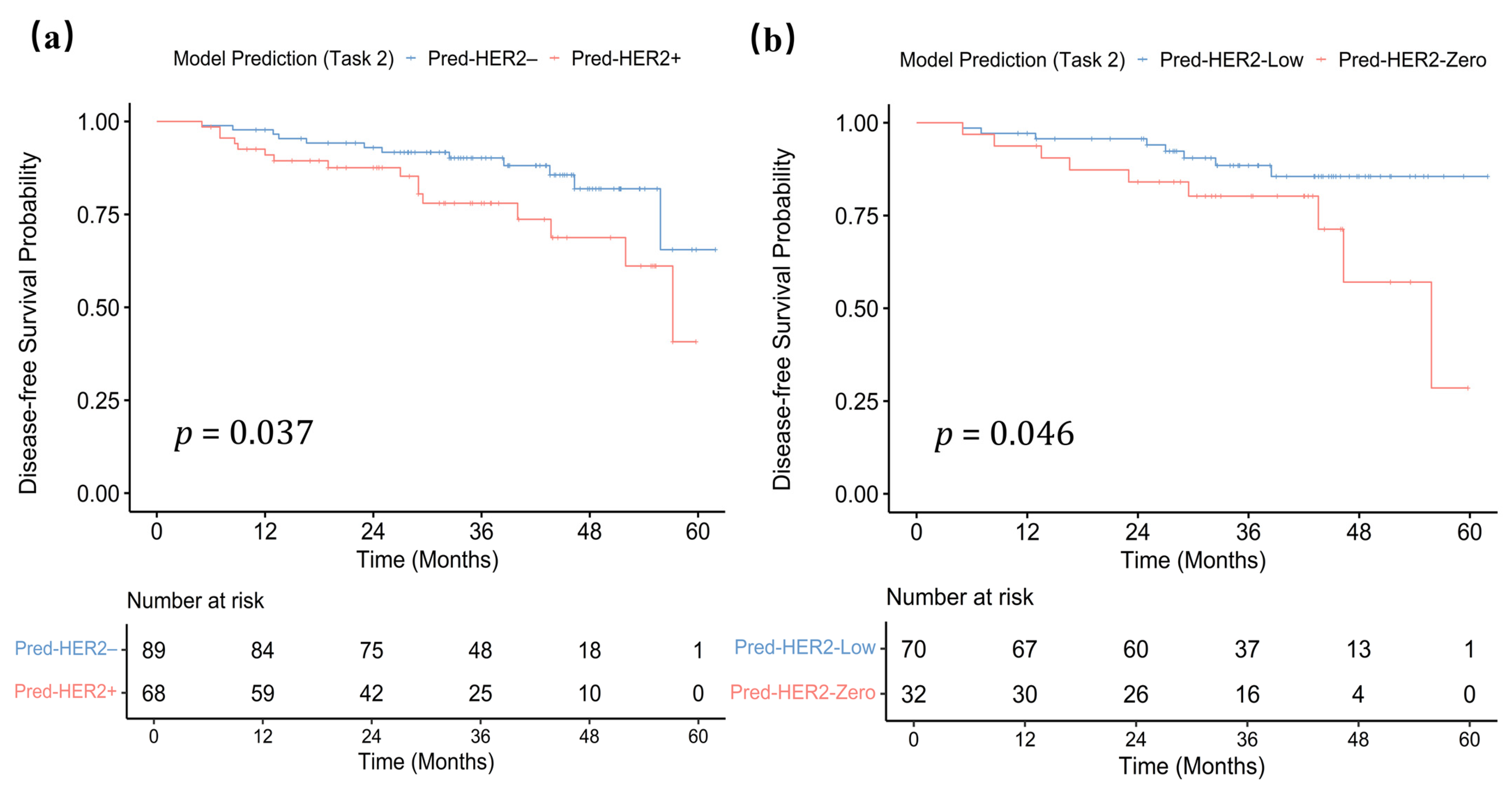

3.5. Task-Specific Survival Analysis

4. Discussion

4.1. Comparison with Prior Studies

4.2. Interpretability and Feature Relevance

4.3. Exploratory Survival Analysis

4.4. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| SHAP | SHapley Additive exPlanation |

| ML | machine learning |

| cMRI | conventional MRI |

| AUC | area under the curve |

| HER2 | human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 |

| IHC | immunohistochemistry |

| FISH | fluorescence in situ hybridization |

| CNB | core needle biopsy |

| MRI | magnetic resonance imaging |

| ER | estrogen receptor |

| PR | progesterone receptor |

| T1WI | T1-weighted images |

| T2WI | T2-weighted images |

| DCE | dynamic contrast-enhanced |

| FGT | fibroglandular tissue |

| BPE | background parenchymal enhancement |

| ALNs | axillary lymph nodes |

| RF | Random Forest |

| SVM | Support Vector Machine |

| XGBoost | eXtreme Gradient Boosting |

| K-NN | K-Nearest Neighbors |

| LR | Logistic Regression |

| ROC | the receiver operating characteristic |

| ACC | accuracy |

| SPE | specificity |

| SEN PPV NPV | sensitivity positive predictive value negative predictive value |

| DFS | disease-free survival |

| ICC | intraclass correlation coefficient |

References

- Cesca, M.G.; Vian, L.; Cristóvão-Ferreira, S.; Pondé, N.; de Azambuja, E. HER2-positive advanced breast cancer treatment in 2020. Cancer Treat. Rev. 2020, 88, 102033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, J.; Wu, Y.; Ma, F.; Kaklamani, V.; Xu, B. Advances in medical treatment of breast cancer in 2022. Cancer Innov. 2023, 2, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Modi, S.; Jacot, W.; Yamashita, T.; Sohn, J.; Vidal, M.; Tokunaga, E.; Tsurutani, J.; Ueno, N.T.; Prat, A.; Chae, Y.S.; et al. Trastuzumab Deruxtecan in Previously Treated HER2-Low Advanced Breast Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2022, 387, 9–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Modi, S.; Park, H.; Murthy, R.K.; Iwata, H.; Tamura, K.; Tsurutani, J.; Moreno-Aspitia, A.; Doi, T.; Sagara, Y.; Redfern, C.; et al. Antitumor Activity and Safety of Trastuzumab Deruxtecan in Patients with HER2-Low-Expressing Advanced Breast Cancer: Results from a Phase Ib Study. J. Clin. Oncol. Off. J. Am. Soc. Clin. Oncol. 2020, 38, 1887–1896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruening, W.; Fontanarosa, J.; Tipton, K.; Treadwell, J.R.; Launders, J.; Schoelles, K. Systematic review: Comparative effectiveness of core-needle and open surgical biopsy to diagnose breast lesions. Ann. Intern. Med. 2010, 152, 238–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolff, A.C.; Hammond, M.E.H.; Allison, K.H.; Harvey, B.E.; Mangu, P.B.; Bartlett, J.M.S.; Bilous, M.; Ellis, I.O.; Fitzgibbons, P.; Hanna, W.; et al. Human Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor 2 Testing in Breast Cancer: American Society of Clinical Oncology/College of American Pathologists Clinical Practice Guideline Focused Update. Arch. Pathol. Lab. Med. 2018, 142, 1364–1382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, Y.; Zhu, S.; Tong, Y.; Fei, X.; Jiang, W.; Shen, K.; Chen, X. HER2-Low Status Is Not Accurate in Breast Cancer Core Needle Biopsy Samples: An Analysis of 5610 Consecutive Patients. Cancers 2022, 14, 6200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Na, S.; Kim, M.; Park, Y.; Kwon, H.J.; Shin, H.C.; Kim, E.K.; Jang, M.; Kim, S.M.; Park, S.Y. Concordance of HER2 status between core needle biopsy and surgical resection specimens of breast cancer: An analysis focusing on the HER2-low status. Breast Cancer 2024, 31, 705–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, S.; Yang, Z.; Du, G.; Zhang, Y.; Jiang, C.; Xu, T.; Li, B.; Wang, D.; Qiu, Y.; Lin, D.; et al. Discrimination between HER2-overexpressing, -low-expressing, and -zero-expressing statuses in breast cancer using multiparametric MRI-based radiomics. Eur. Radiol. 2024, 34, 6132–6144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeng, Q.; Liu, L.; He, C.; Zeng, X.; Wei, P.; Xu, D.; Mao, N.; Yu, T. Early and noninvasive prediction of response to neoadjuvant therapy for breast cancer via longitudinal ultrasound and MR deep learning: A multicentre study. Acad. Radiol. 2025, 32, 1264–1273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, Y.; Xie, X.; Tang, W.; Chen, S.; Wang, M.; Fan, Y.; Lin, C.; Hu, W.; Yang, J.; Xiang, J.; et al. Noninvasive identification of HER2-low-positive status by MRI-based deep learning radiomics predicts the disease-free survival of patients with breast cancer. Eur. Radiol. 2024, 34, 899–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramtohul, T.; Djerroudi, L.; Lissavalid, E.; Nhy, C.; Redon, L.; Ikni, L.; Djelouah, M.; Journo, G.; Menet, E.; Cabel, L.; et al. Multiparametric MRI and Radiomics for the Prediction of HER2-Zero, -Low, and -Positive Breast Cancers. Radiology 2023, 308, e222646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bian, X.; Du, S.; Yue, Z.; Gao, S.; Zhao, R.; Huang, G.; Guo, L.; Peng, C.; Zhang, L. Potential Antihuman Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor 2 Target Therapy Beneficiaries: The Role of MRI-Based Radiomics in Distinguishing Human Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor 2-Low Status of Breast Cancer. J. Magn. Reson. Imaging JMRI 2023, 58, 1603–1614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.; Chen, S.; Tang, W.; Kong, Q.; Zhong, Z.; Yu, X.; Sui, Y.; Hu, W.; Jiang, X.; Guo, Y. Multiparametric MRI Radiomics with Machine Learning for Differentiating HER2-Zero, -Low, and -Positive Breast Cancer: Model Development, Testing, and Interpretability Analysis. AJR Am. J. Roentgenol. 2025, 224, e2431717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, C.; Hu, L.; Jiang, W.; Qiu, Y.; Yang, Z.; Liu, Y.; Wang, M.; Wang, D.; Su, Y.; Lin, J.; et al. Discrimination between human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2)-low-expressing and HER2-overexpressing breast cancers: A comparative study of four MRI diffusion models. Eur. Radiol. 2024, 34, 2546–2559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, W.; Yang, Y.; Wang, X.; Li, C.; Liu, C.; Li, X.; Wen, J.; Lin, X.; Qin, J. A Comprehensive Model Outperformed the Single Radiomics Model in Noninvasively Predicting the HER2 Status in Patients with Breast Cancer. Acad. Radiol. 2025, 32, 24–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, H.J.; Ren, J.L.; Mei Guo, L.; Liang Niu, J.; Song, X.L. MRI-based machine learning radiomics for prediction of HER2 expression status in breast invasive ductal carcinoma. Eur. J. Radiol. Open 2024, 13, 100592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cè, M.; Chiriac, M.D.; Cozzi, A.; Macrì, L.; Rabaiotti, F.L.; Irmici, G.; Fazzini, D.; Carrafiello, G.; Cellina, M. Decoding Radiomics: A Step-by-Step Guide to Machine Learning Workflow in Hand-Crafted and Deep Learning Radiomics Studies. Diagnostics 2024, 14, 2473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Truhn, D.; Schrading, S.; Haarburger, C.; Schneider, H.; Merhof, D.; Kuhl, C. Radiomic versus Convolutional Neural Networks Analysis for Classification of Contrast-enhancing Lesions at Multiparametric Breast MRI. Radiology 2019, 290, 290–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Zhang, Y.; Miao, H.; Yoon, G.Y.; Wang, J.; Lin, Y.; Wang, H.; Liu, Y.L.; Chen, J.H.; Pan, Z.; et al. Preoperative Differentiation of HER2-Zero and HER2-Low from HER2-Positive Invasive Ductal Breast Cancers Using BI-RADS MRI Features and Machine Learning Modeling. J. Magn. Reson. Imaging JMRI 2025, 61, 928–941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elshawi, R.; Al-Mallah, M.H.; Sakr, S. On the interpretability of machine learning-based model for predicting hypertension. BMC Med. Inform. Decis. Mak. 2019, 19, 146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petch, J.; Di, S.; Nelson, W. Opening the Black Box: The Promise and Limitations of Explainable Machine Learning in Cardiology. Can. J. Cardiol. 2022, 38, 204–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ejiyi, C.J.; Qin, Z.; Monday, H.; Ejiyi, M.B.; Ukwuoma, C.; Ejiyi, T.U.; Agbesi, V.K.; Agu, A.; Orakwue, C. Breast cancer diagnosis and management guided by data augmentation, utilizing an integrated framework of SHAP and random augmentation. BioFactors 2024, 50, 114–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; Xu, J.; Li, M.; Jiang, Z.; Mao, J.; Feng, L.; Miao, K.; Li, H.; Chen, J.; Bai, Z.; et al. Identification and validation of an explainable prediction model of acute kidney injury with prognostic implications in critically ill children: A prospective multicenter cohort study. EClinicalMedicine 2024, 68, 102409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, M.; Liu, R.; Wen, C.; Xu, W.; Xu, Z.; Wang, S.; Wu, J.; Pan, D.; Zheng, B.; Qin, G.; et al. Predicting the molecular subtype of breast cancer and identifying interpretable imaging features using machine learning algorithms. Eur. Radiol. 2022, 32, 1652–1662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Wang, X.; Cao, Y.; Li, M.; Li, L.; Chen, H.; Tang, S.; Lan, X.; Jiang, F.; Zhang, J. Multiparametric MRI model to predict molecular subtypes of breast cancer using Shapley additive explanations interpretability analysis. Diagn. Interv. Imaging 2024, 105, 191–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rominger, M.; Berg, D.; Frauenfelder, T.; Ramaswamy, A.; Timmesfeld, N. Which factors influence MRI-pathology concordance of tumour size measurements in breast cancer? Eur. Radiol. 2016, 26, 1457–1465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, J.M.; Leung, J.W.T.; Moy, L.; Ha, S.M.; Moon, W.K. Axillary Nodal Evaluation in Breast Cancer: State of the Art. Radiology 2020, 295, 500–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Şen, G.A.; Aydın, E.; Guliyev, M.; Öztaş, N.; Değerli, E.; Demirci, N.S.; Turna, Z.H.; Demirelli, F.H. The impact of HER2-low status on pathological complete response and disease-free survival in early-stage breast cancer. BMC Cancer 2024, 24, 1311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poulter, N.R.; Chang, C.L.; Farley, T.M.; Marmot, M.G. Reliability of data from proxy respondents in an international case-control study of cardiovascular disease and oral contraceptives. World Health Organization Collaborative Study of Cardiovascular Disease and Steroid Hormone Contraception. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 1996, 50, 674–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landis, J.R.; Koch, G.G. The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics 1977, 33, 159–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, Y.; Zhang, X.; Qiu, Y.; Li, B.; Yang, Z.; Huang, J.; Lin, J.; Zheng, C.; Hu, L.; Shen, J. Development and Validation of MRI Radiomics Models to Differentiate HER2-Zero, -Low, and -Positive Breast Cancer. AJR Am. J. Roentgenol. 2024, 222, e2330603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, W.; Liu, C.; Yang, Y.; Chen, Y.; Muhetaier, A.; Lin, Z.; Weng, Z.; Wang, X.; Zhang, P.; Qin, J. Combining conventional magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) parameters with clinicopathologic data for differentiation of the three-tiered human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2) status in breast cancer. Clin. Radiol. 2025, 86, 106955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Tsang, J.Y.; Tam, F.; Loong, T.; Tse, G.M. Comprehensive characterization of HER2-low breast cancers: Implications in prognosis and treatment. eBioMedicine 2023, 91, 104571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Ma, Y.; Li, Y.; Yu, Y.; Lu, B.; Liao, L.; Li, F.; Wen, Z.; Jiang, W.; Guo, P.; et al. Bioinformatics combined with clinical data to analyze clinical characteristics and prognosis in patients with HER2 low expression breast cancer. Gland. Surg. 2023, 12, 197–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schettini, F.; Chic, N.; Brasó-Maristany, F.; Paré, L.; Pascual, T.; Conte, B.; Martínez-Sáez, O.; Adamo, B.; Vidal, M.; Barnadas, E.; et al. Clinical, pathological, and PAM50 gene expression features of HER2-low breast cancer. npj Breast Cancer 2021, 7, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denkert, C.; Seither, F.; Schneeweiss, A.; Link, T.; Blohmer, J.U.; Just, M.; Wimberger, P.; Forberger, A.; Tesch, H.; Jackisch, C.; et al. Clinical and molecular characteristics of HER2-low-positive breast cancer: Pooled analysis of individual patient data from four prospective, neoadjuvant clinical trials. Lancet Oncol. 2021, 22, 1151–1161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Feature | Training Set (n = 377) | Internal Test Set (n = 157) | External Test Set (n = 144) | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (y), mean ± SD | 54.69 ± 11.12 | 54.85 ± 10.54 | 52.76 ± 10.18 | 0.811 |

| Menopausal status | 0.165 | |||

| Yes | 248 (65.78) | 105 (66.88) | 83 (57.64) | |

| No | 129 (34.22) | 52 (33.12) | 61 (42.36) | |

| Location | 0.377 | |||

| Left | 203 (53.85) | 77 (49.04) | 82 (56.94) | |

| Right | 174 (46.15) | 80 (50.96) | 62 (43.06) | |

| Histologic type | 0.135 | |||

| NST | 350 (92.84) | 145 (92.36) | 126 (87.50) | |

| ILC and other | 27 (7.16) | 12 (7.64) | 18 (12.50) | |

| HER2 expression | 0.286 | |||

| HER2-positive | 98 (25.99) | 55 (35.03) | 42 (29.17) | |

| HER2-low | 195 (51.72) | 68 (43.31) | 73 (50.69) | |

| HER2-zero | 84 (22.28) | 34 (21.66) | 29 (20.14) | |

| ER | 0.932 | |||

| Positive | 296 (78.51) | 121 (77.07) | 112 (77.78) | |

| Negative | 81 (21.49) | 36 (22.93) | 32 (22.22) | |

| PR | 0.539 | |||

| Positive | 270 (71.62) | 111 (70.70) | 96 (66.67) | |

| Negative | 107 (28.38) | 46 (29.30) | 48 (33.33) | |

| Ki67 | 0.489 | |||

| ≤14% | 294 (77.98) | 115 (73.25) | 109 (75.69) | |

| >14% | 83 (22.02) | 42 (26.75) | 35 (24.31) |

| Feature | Training Set (n = 377) | Internal Test Set (n = 157) | External Test Set (n = 144) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HER2- Positive (n = 98) | HER2- Negative (n = 279) | p | HER2- Positive (n = 55) | HER2- Negative (n = 102) | p | HER2- Positive (n = 42) | HER2- Negative (n = 102) | p | |

| Tumor size (mm) | 33.44 ± 17.40 | 28.99 ± 18.07 | 0.03 | 29.62 ± 12.61 | 24.42 ± 11.91 | 0.01 | 31.02 ± 12.11 | 25.59 ± 12.63 | 0.02 |

| FGT | 0.34 | 0.11 | 0.83 | ||||||

| Fatty/scattered | 43 (43.88) | 140 (50.18) | 19 (34.55) | 50 (49.02) | 17 (40.48) | 45 (44.12) | |||

| Heterogeneous/extremely dense | 55 (56.12) | 139 (49.82) | 36 (65.45) | 52 (50.98) | 25 (59.52) | 57 (55.88) | |||

| BPE | >0.99 | >0.99 | 0.14 | ||||||

| Minimal/mild | 80 (81.63) | 228 (81.72) | 48 (87.27) | 89 (87.25) | 36 (85.71) | 74 (72.55) | |||

| Moderate/marked | 18 (18.37) | 51 (18.28) | 7 (12.73) | 13 (12.75) | 6 (14.29) | 28 (27.45) | |||

| Multifocal | 0.20 | 0.10 | 0.12 | ||||||

| Single | 50 (51.02) | 165 (59.14) | 28 (50.91) | 67 (65.69) | 22 (52.38) | 69 (67.65) | |||

| Multiple | 48 (48.98) | 114 (40.86) | 27 (49.09) | 35 (34.31) | 20 (47.62) | 33 (32.35) | |||

| Tumor shape | 0.16 | >0.99 a | 0.72 a | ||||||

| Round/oval | 2 (2.04) | 18 (6.45) | 1 (1.82) | 2 (1.96) | 2 (4.76) | 8 (7.84) | |||

| Irregular | 96 (97.96) | 261 (93.55) | 54 (98.18) | 100 (98.04) | 40 (95.24) | 94 (92.16) | |||

| Tumor margin | 0.07 | 0.34 | 0.33 | ||||||

| Circumscribed | 7 (7.14) | 42 (15.05) | 4 (7.27) | 14 (13.73) | 3 (7.14) | 15 (14.71) | |||

| Not circumscribed | 91 (92.86) | 237 (84.95) | 51 (92.73) | 88 (86.27) | 39 (92.86) | 87 (85.29) | |||

| Mass internal enhancement | 0.58 | >0.99 a | 0.23 a | ||||||

| Homogeneous | 7 (7.14) | 27 (9.68) | 3 (5.45) | 7 (6.86) | 2 (4.76) | 13 (12.75) | |||

| Heterogeneous | 91 (92.86) | 252 (90.32) | 52 (94.55) | 95 (93.14) | 40 (95.24) | 89 (87.25) | |||

| Enhancement curve | 0.75 | 0.25 a | >0.99 | ||||||

| Ascendant and/or plateau | 186 (87.76) | 250 (89.61) | 48 (87.27) | 95 (93.14) | 36 (85.71) | 87 (85.29) | |||

| Washout | 12 (12.24) | 29 (10.39) | 7 (12.73) | 7 (6.86) | 6 (14.29) | 15 (14.71) | |||

| Nonmass enhancement | 0.15 | 0.48 | 0.16 | ||||||

| Absent | 70 (71.43) | 221 (79.21) | 39 (70.91) | 79 (77.45) | 31 (73.81) | 87 (85.29) | |||

| Present | 28 (28.57) | 58 (20.79) | 16 (29.09) | 23 (22.55) | 11 (26.19) | 15 (14.71) | |||

| Peritumoral edema | 0.02 | <0.001 | 0.002 | ||||||

| Absent | 23 (23.47) | 104 (37.28) | 7 (12.73) | 45 (44.12) | 7 (16.67) | 46 (45.10) | |||

| Present | 75 (76.53) | 175 (62.72) | 48 (87.27) | 57 (55.88) | 35 (83.33) | 56 (54.90) | |||

| Abnormal ALNs | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||||||

| Absent | 37 (37.76) | 181 (64.87) | 14 (25.45) | 57 (55.88) | 15 (35.71) | 74 (72.55) | |||

| Present | 61 (62.24) | 98 (35.13) | 41 (74.55) | 45 (44.12) | 27 (64.29) | 28 (27.45) | |||

| Feature | Training Set (n = 279) | Internal Test Set (n = 102) | External Test Set (n = 102) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HER2- Low (n = 195) | HER2- Zero (n = 84) | p | HER2- Low (n = 68) | HER2- Zero (n = 34) | p | HER2- Low (n = 73) | HER2- Zero (n = 29) | p | |

| Tumor size (mm) | 30.01 ± 19.10 | 26.62 ± 15.24 | 0.15 | 24.14 ± 11.34 | 24.98 ± 13.14 | 0.74 | 26.26 ± 13.24 | 23.90 ± 10.97 | 0.40 |

| FGT | 0.72 | 0.94 | 0.43 | ||||||

| Fatty/scattered | 96 (49.23) | 44 (52.38) | 34 (50.00) | 16 (47.06) | 34 (46.58) | 11 (37.93) | |||

| Heterogeneous/extremely dense | 99 (50.77) | 40 (47.62) | 34 (50.00) | 18 (52.94) | 39 (53.42) | 18 (62.07) | |||

| BPE | 0.96 | 0.76 | 0.99 | ||||||

| Minimal/mild | 160 (82.95) | 68 (80.95) | 60 (88.24) | 29 (85.29) | 53 (72.60) | 21 (72.41) | |||

| Moderate/marked | 35 (17.95) | 16 (19.05) | 8 (11.76) | 5 (14.71) | 20 (27.40) | 8 (27.59) | |||

| Multifocal | 0.31 | 0.34 | 0.11 | ||||||

| Single | 111 (56.92) | 54 (64.29) | 42 (61.76) | 25 (73.53) | 47 (64.38) | 23 (79.31) | |||

| Multiple | 84 (43.08) | 30 (35.71) | 26 (38.24) | 9 (26.47) | 26 (35.62) | 6 (20.69) | |||

| Tumor shape | >0.99 | 0.55 a | 0.22 a | ||||||

| Round/oval | 13 (6.67) | 5 (5.95) | 2 (2.94) | 0 (0.00) | 4 (5.48) | 4 (13.79) | |||

| Irregular | 182 (93.33) | 79 (94.05) | 66 (97.06) | 34 (100.00) | 69 (94.52) | 25 (86.21) | |||

| Tumor margin | 0.16 | >0.99 a | 0.76 a | ||||||

| Circumscribed | 25 (12.82) | 17 (20.24) | 9 (14.71) | 5 (14.71) | 10 (13.70) | 5 (17.24) | |||

| Not circumscribed | 170 (87.18) | 67 (79.76) | 59 (85.76) | 29 (85.29) | 63 (86.30) | 24 (82.76) | |||

| Mass internal enhancement | >0.99 | 0.42 a | >0.99 a | ||||||

| Homogeneous | 19 (9.74) | 8 (9.52) | 6 (8.82) | 1 (2.94) | 9 (12.33) | 3 (10.34) | |||

| Heterogeneous | 176 (90.26) | 76 (90.48) | 62 (91.18) | 33 (97.06) | 64 (87.67) | 26 (89.66) | |||

| Enhancement curve | 0.17 | >0.99 a | 0.06 a | ||||||

| Ascendant and/or plateau | 171 (87.69) | 79 (94.05) | 63 (92.65) | 32 (94.12) | 59 (80.82) | 28 (96.55) | |||

| Washout | 24 (12.31) | 5 (5.95) | 5 (7.35) | 2 (5.88) | 14 (19.18) | 1 (3.45) | |||

| Nonmass enhancement | 0.99 | 0.68 | 0.22 a | ||||||

| Absent | 155 (79.49) | 66 (78.57) | 54 (79.41) | 25 (73.53) | 60 (82.19) | 27 (93.10) | |||

| Present | 40 (20.51) | 18 (21.43) | 14 (20.59) | 9 (26.47) | 13 (17.81) | 2 (6.90) | |||

| Peritumoral edema | 0.052 | 0.83 | 0.08 | ||||||

| Absent | 65 (33.33) | 39 (46.43) | 29 (42.65) | 16 (47.06) | 29 (39.73) | 17 (58.62) | |||

| Present | 130 (66.67) | 45 (53.57) | 39 (57.35) | 18 (52.94) | 44 (60.27) | 12 (41.38) | |||

| Abnormal ALNs | 0.27 | 0.29 | 0.15 | ||||||

| Absent | 122 (62.56) | 59 (70.24) | 41 (60.29) | 16 (47.06) | 50 (68.49) | 24 (82.76) | |||

| Present | 73 (37.44) | 25 (29.76) | 27 (39.71) | 18 (52.94) | 23 (31.51) | 5 (17.24) | |||

| Task 1, Sets | AUC (95% CI) | ACC | SEN | SPE | PPV | NPV |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Training set | 0.97 (0.96–0.98) | 89.1 | 90.0 | 88.2 | 88.4 | 89.8 |

| Internal test set | 0.75 (0.67–0.82) | 71.3 | 70.9 | 71.6 | 57.4 | 82.0 |

| External test set | 0.73 (0.64–0.82) | 68.8 | 66.7 | 69.6 | 47.5 | 83.5 |

| Task 2, Sets | ||||||

| Training set | 0.93 (0.90–0.95) | 85.4 | 86.7 | 84.1 | 84.5 | 86.3 |

| Internal test set | 0.73 (0.61–0.83) | 76.5 | 83.8 | 61.8 | 81.4 | 65.6 |

| External test set | 0.72 (0.60–0.83) | 71.6 | 75.3 | 62.1 | 83.3 | 50.0 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Chen, Y.; Liu, W.; Tang, W.; Kong, Q.; Chen, S.; Liu, S.; Pan, L.; Guo, Y.; Jiang, X. Machine Learning Model Based on Multiparametric MRI for Distinguishing HER2 Expression Level in Breast Cancer. Curr. Oncol. 2026, 33, 53. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol33010053

Chen Y, Liu W, Tang W, Kong Q, Chen S, Liu S, Pan L, Guo Y, Jiang X. Machine Learning Model Based on Multiparametric MRI for Distinguishing HER2 Expression Level in Breast Cancer. Current Oncology. 2026; 33(1):53. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol33010053

Chicago/Turabian StyleChen, Yongxin, Weifeng Liu, Wenjie Tang, Qingcong Kong, Siyi Chen, Shuang Liu, Liwen Pan, Yuan Guo, and Xinqing Jiang. 2026. "Machine Learning Model Based on Multiparametric MRI for Distinguishing HER2 Expression Level in Breast Cancer" Current Oncology 33, no. 1: 53. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol33010053

APA StyleChen, Y., Liu, W., Tang, W., Kong, Q., Chen, S., Liu, S., Pan, L., Guo, Y., & Jiang, X. (2026). Machine Learning Model Based on Multiparametric MRI for Distinguishing HER2 Expression Level in Breast Cancer. Current Oncology, 33(1), 53. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol33010053