Towards Cervical Cancer Elimination: Insights from an In-Depth Regional Review of Patients with Cervical Cancer

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

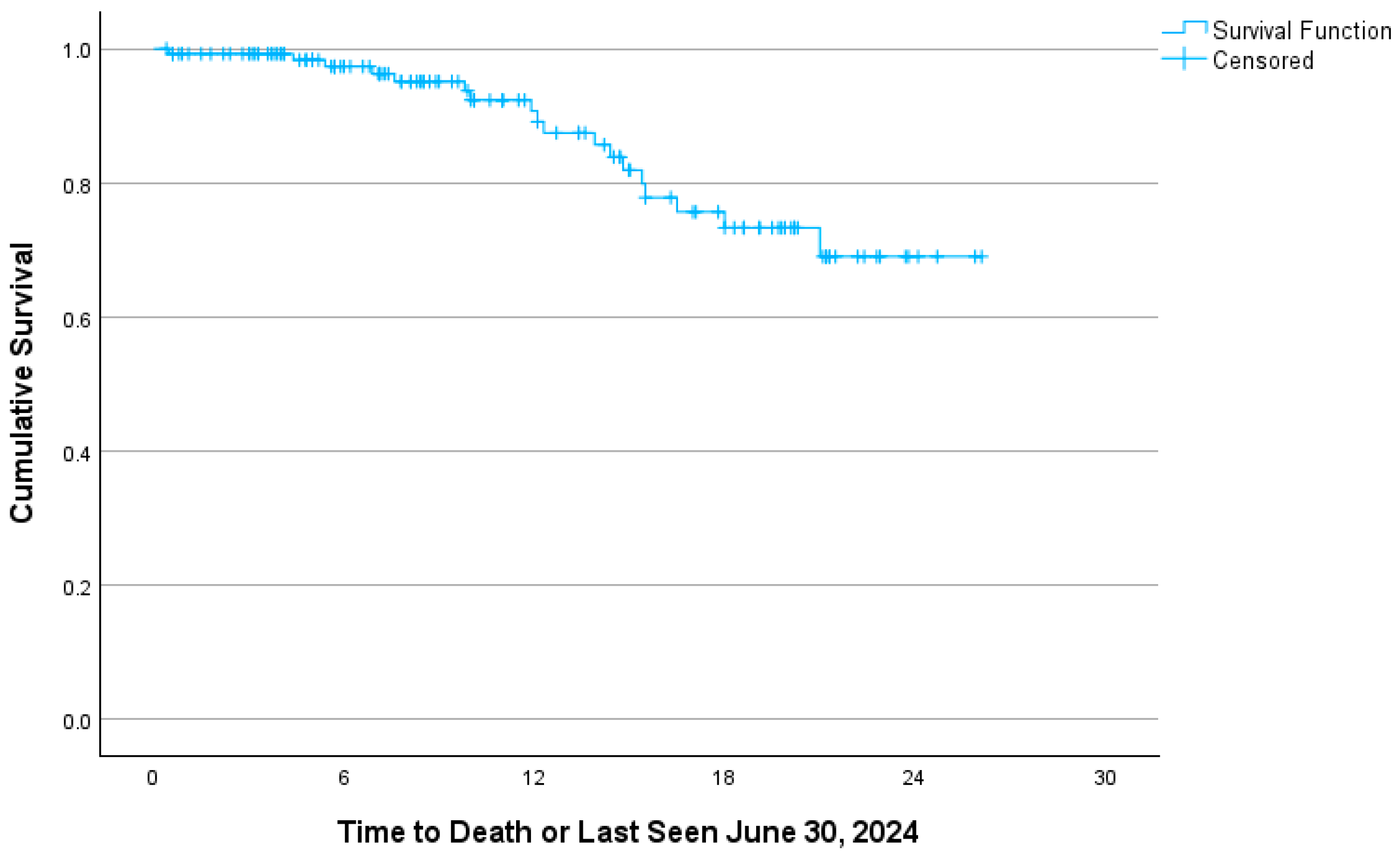

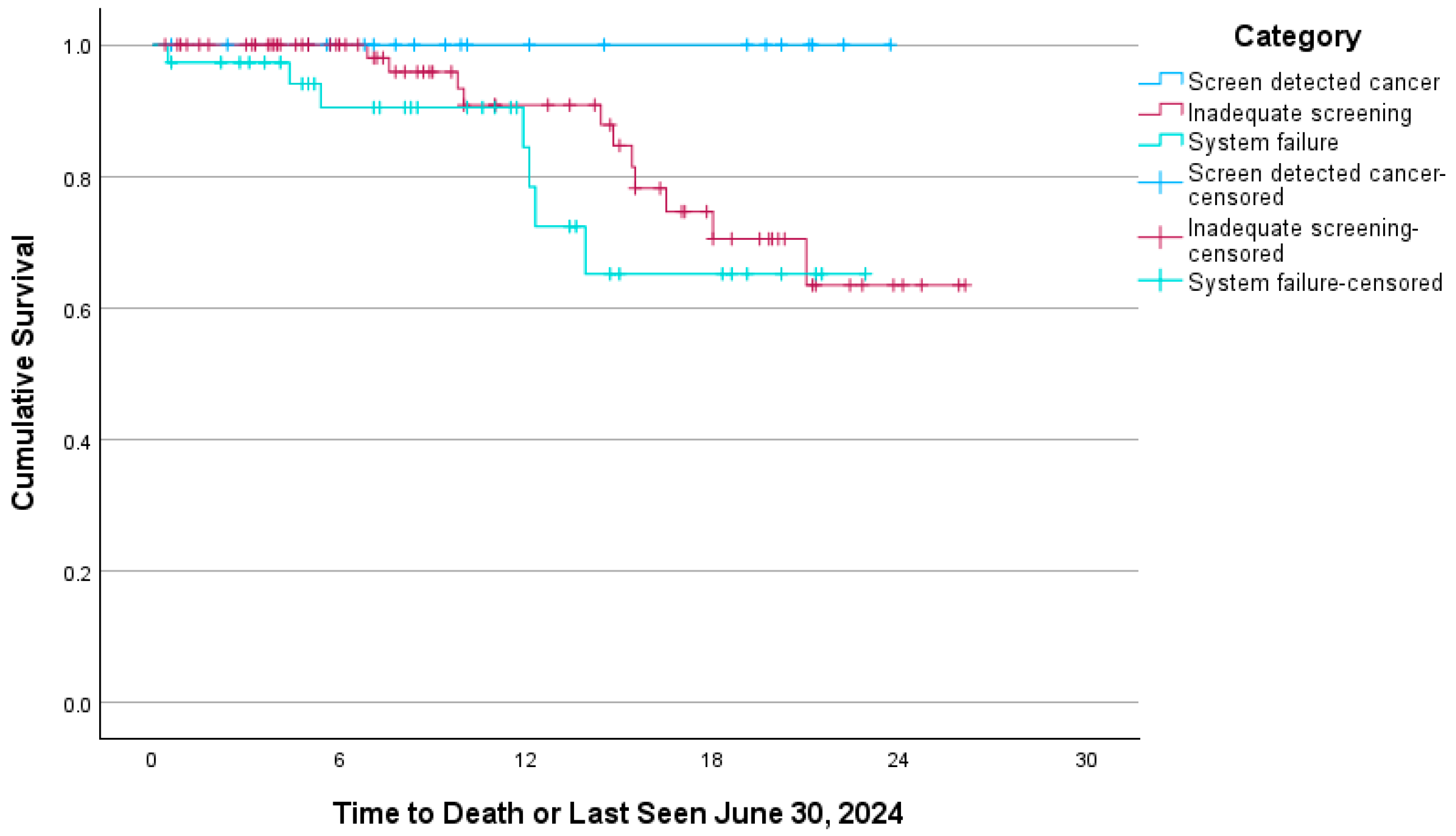

3. Results

4. Interpretation

- •

- Increase HPV vaccination.

- •

- Encourage smoking cessation.

- •

- Adopt the higher sensitivity HPV screening test.

- •

- Adopt HPV self-testing to address patient barriers to engagement, geography, and access to primary care.

- •

- Offer opportunities for cervical screening for unattached individuals.

- •

- Ensure access to cervical screening for new immigrants and refugees.

- •

- Consider equity-focused screening delivery to ensure uptake by populations underserved by current practices, i.e., psychiatric diagnoses, rural, and low socio-economic status.

- •

- Strengthen cervical screening registries.

- •

- Employ patient-specific electronic reminders to prompt engagement and decrease loss to follow-up.

- •

- Ensure transgender individuals receive appropriate screening.

- •

- Ensure ongoing screening of patients treated for cervical dysplasia who remain at elevated risk.

- •

- Ensure appropriate cessation of screening.

- •

- Consider extending screening beyond age 69, depending on the individual’s overall health and functional status, clinical history, and risk factors.

- •

- Implement opportunistic screening at medical touchpoints involving the cervix, including therapeutic abortions, IUD insertions, and pregnancy care.

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Guan, P.; Howell-Jones, R.; Li, N.; Bruni, L.; De Sanjosé, S.; Franceschi, S.; Clifford, G.M. Human papillomavirus types in 115,789 HPV-positive women: A meta-analysis from cervical infection to cancer. Int. J. Cancer 2012, 131, 2349–2359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falcaro, M.; Castañon, A.; Ndlela, B.; Checchi, M.; Soldan, K.; Lopez-Bernal, J.; Elliss-Brookes, L.; Sasieni, P. The effects of the national HPV vaccination programme in England, UK, on cervical cancer and grade 3 cervical intraepithelial neoplasia incidence: A register-based observational study. Lancet 2021, 398, 2084–2092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perkins, R.B.; Wentzensen, N.; Guido, R.S.; Schiffman, M. Cervical Cancer Screening: A Review. JAMA 2023, 330, 547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CPAC. Available online: https://www.partnershipagainstcancer.ca/topics/eliminating-cervical-cancer/ (accessed on 30 June 2025).

- Cancer Statistics. 2023. Available online: https://cdn.cancer.ca/-/media/files/research/cancer-statistics/2023-statistics/2023_PDF_EN.pdf (accessed on 30 June 2025).

- Nicolau, I.A.; Warkentin, M.T.; Graff, K.; Doll, C.; Bryant, H.; Brenner, D.R. Increasing Cervical Cancer Rates Among Women Age 35–54 Years in Canada: Age-Specific Cervical Cancer Incidence Trends in Canada, 1992–2022. JCO Oncol. Adv. 2025, 2, e2400101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caird, H.; Simkin, J.; Smith, L.; Van Niekerk, D.; Ogilvie, G. The Path to Eliminating Cervical Cancer in Canada: Past, Present and Future Directions. Curr. Oncol. 2022, 29, 1117–1122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canadian Task Force on Preventive Health Care. Recommendations on screening for cervical cancer. Can. Med. Assoc. J. 2013, 185, 35–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ogilvie, G.S.; Van Niekerk, D.; Krajden, M.; Smith, L.W.; Cook, D.; Gondara, L.; Ceballos, K.; Quinlan, D.; Lee, M.; Martin, R.E.; et al. Effect of Screening With Primary Cervical HPV Testing vs Cytology Testing on High-grade Cervical Intraepithelial Neoplasia at 48 Months: The HPV FOCAL Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA 2018, 320, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delpero, E.; Selk, A. Shifting from cytology to HPV testing for cervical cancer screening in Canada. Can. Med. Assoc. J. 2022, 194, E613–E615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saraiya, M.; Steben, M.; Watson, M.; Markowitz, L. Evolution of cervical cancer screening and prevention in United States and Canada: Implications for public health practitioners and clinicians. Prev. Med. 2013, 57, 426–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ogilvie, G.S.; Krajden, M.; Van Niekerk, D.J.; Martin, R.E.; Ehlen, T.G.; Ceballos, K.; Smith, L.W.; Kan, L.; Cook, D.A.; Peacock, S.; et al. Primary cervical cancer screening with HPV testing compared with liquid-based cytology: Results of round 1 of a randomised controlled trial—The HPV FOCAL Study. Br. J. Cancer 2012, 107, 1917–1924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cancer Care Ontario. Ontario Cervical Screening Program. Available online: https://www.cancercareontario.ca/en/cancer-care-ontario/programs/screening-programs/ontario-cervical (accessed on 18 June 2025).

- Ontario Marginalization Index (ON-Marg). Available online: https://www.publichealthontario.ca/en/Data-and-Analysis/Health-Equity/Ontario-Marginalization-Index (accessed on 30 May 2025).

- Learn More About the Rurality Index for Ontario Score. Available online: https://www.ontario.ca/document/northern-health-programs/learn-more-about-rurality-index-ontario-score (accessed on 30 May 2025).

- 2016 Census. Available online: https://www12.statcan.gc.ca/census-recensement/2016/dp-pd/prof/index.cfm?Lang=E (accessed on 12 May 2025).

- Ontario Cancer Statistics. 2024. Available online: https://www.cancercareontario.ca/en/statistical-reports/ontario-cancer-statistics-2024 (accessed on 30 June 2025).

- White Paper. Canada’s Strategy to Combat HPV-Related Consequences and Eliminate Cervical Cancer. Available online: https://hpvglobalaction.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/01/White-Report-Canadas-Strategy-to-Combat-HPV-Related-Consequences-and-Eliminate-Cervical-Cancer-1.pdf (accessed on 30 June 2025).

- Benard, V.B.; Jackson, J.E.; Greek, A.; Senkomago, V.; Huh, W.K.; Thomas, C.C.; Richardson, L.C. A population study of screening history and diagnostic outcomes of women with invasive cervical cancer. Cancer Med. 2021, 10, 4127–4137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Semenciw, R.; Mao, Y. Cervical cancer: The increasing incidence of adenocarcinoma and adenosquamous carcinoma in younger women. CMAJ Can. Med. Assoc. J. 2001, 164, 1151–1152. [Google Scholar]

- Ronco, G.; Dillner, J.; Elfström, K.M.; Tunesi, S.; Snijders, P.J.F.; Arbyn, M.; Kitchener, H.; Segnan, N.; Gilham, C.; Giorgi-Rossi, P.; et al. Efficacy of HPV-based screening for prevention of invasive cervical cancer: Follow-up of four European randomised controlled trials. Lancet 2014, 383, 524–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herbert, A.; Anshu; Culora, G.; Dunsmore, H.; Gupta, S.; Holdsworth, G.; Kubba, A.; McLean, E.; Sim, J.; Raju, K. Invasive cervical cancer audit: Why cancers developed in a high-risk population with an organised screening programme. BJOG Int. J. Obs. Gynaecol. 2010, 117, 736–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kirschner, B.; Poll, S.; Rygaard, C.; Wåhlin, A.; Junge, J. Screening history in women with cervical cancer in a Danish population-based screening program. Gynecol. Oncol. 2011, 120, 68–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spayne, J.; Ackerman, I.; Milosevic, M.; Seidenfeld, A.; Covens, A.; Paszat, L. Invasive cervical cancer: A failure of screening. Eur. J. Public Health 2007, 18, 162–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Champlain Screening Outreach Program. Available online: https://www.ottawahospital.on.ca/en/clinical-services/deptpgrmcs/programs/cancer-program/what-we-offer-our-programs-and-services/champlain-screening-outreach-program/ (accessed on 10 June 2025).

- Clarke, M.A.; Fetterman, B.; Cheung, L.C.; Wentzensen, N.; Gage, J.C.; Katki, H.A.; Befano, B.; Demarco, M.; Schussler, J.; Kinney, W.K.; et al. Epidemiologic Evidence That Excess Body Weight Increases Risk of Cervical Cancer by Decreased Detection of Precancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2018, 36, 1184–1191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferdous, M.; Lee, S.; Goopy, S.; Yang, H.; Rumana, N.; Abedin, T.; Turin, T.C. Barriers to cervical cancer screening faced by immigrant women in Canada: A systematic scoping review. BMC Women’s Health 2018, 18, 165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McDonald, J.T.; Kennedy, S. Cervical Cancer Screening by Immigrant and Minority Women in Canada. J. Immigr. Minor. Health 2007, 9, 323–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sand, F.L.; Frederiksen, K.; Munk, C.; Jensen, S.M.; Kjær, S.K. Long-term risk of cervical cancer following conization of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade 3—A Danish nationwide cohort study. Int. J. Cancer 2018, 142, 1759–1766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- HPV-Associated Cancers and Precancers. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/std/treatment-guidelines/hpv-cancer.htm#:~:text=After%20treatment%20for%20a%20high%2Dgrade%20precancer%20(moderate,6%2C%2012%2C%2018%2C%2024%2C%20and%2030%20months (accessed on 30 June 2025).

- Katki, H.A.; Schiffman, M.; Castle, P.E.; Fetterman, B.; Poitras, N.E.; Lorey, T.; Cheung, L.C.; Raine-Bennett, T.; Gage, J.C.; Kinney, W.K. Five-Year Risk of Recurrence After Treatment of CIN 2, CIN 3, or AIS: Performance of HPV and Pap Cotesting in Posttreatment Management. J. Low. Genit. Tract Dis. 2013, 17, S78–S84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arbyn, M.; Redman, C.W.E.; Verdoodt, F.; Kyrgiou, M.; Tzafetas, M.; Ghaem-Maghami, S.; Petry, K.-U.; Leeson, S.; Bergeron, C.; Nieminen, P.; et al. Incomplete excision of cervical precancer as a predictor of treatment failure: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Oncol. 2017, 18, 1665–1679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cooley, J.J.P.; Maguire, F.B.; Morris, C.R.; Parikh-Patel, A.; Abrahão, R.; Chen, H.A.; Keegan, T.H.M. Cervical Cancer Stage at Diagnosis and Survival among Women ≥65 Years in California. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 2023, 32, 91–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Edvardsson, H.; Strander, B.; Andrae, B.; Sparén, P.; Dillner, J. Long-term follow-up of cervical cancer incidence after normal cytological findings. Int. J. Cancer 2024, 154, 448–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Category | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Screen detected | Inadequate Screening | System failure | ||

| n = 22 (%) | n = 73 (%) | n = 37 (%) | ||

| Mean | p-value | |||

| Age | 44.4 | 53.8 | 47.9 | 0.014 |

| BMI | 22.0 | 25.2 | 24.5 | 0.151 |

| N | ||||

| BMI Underweight (<18.5) | 5 (22.7) | 10 (13.7) | 10 (27.0) | 0.196 |

| BMI Healthy weight (18.5–24.9) | 12 (54.5) | 29 (39.7) | 14 (37.8) | |

| BMI Overweight (25.0–29.9) | 3 (13.6) | 20 (27.4) | 4 (10.8) | |

| BMI Obese (30.0+) | 2 (9.1) | 14 (19.2) | 8 (21.6) | |

| Cases diagnosed after age 70 | 0 (0.0) | 10 (13.7) | 3 (8.1) | 0.170 |

| Ever smoker | 12 (54.5) | 39 (53.4) | 16 (43.2) | 0.637 |

| At least one comorbidity | 8 (36.4) | 36 (49.3) | 13 (35.1) | 0.223 |

| Pre-existing psychiatric diagnosis | 6 (27.3) | 23 (31.5) | 8 (21.6) | 0.550 |

| No primary care provider | 0 (0.0) | 17 (23.3) | 1 (2.7) | 0.001 |

| History of dysplasia treatment | 6 (27.3) | 12 (16.4) | 6 (16.2) | 0.480 |

| Rural | 6 (27.3) | 39 (53.4) | 14 (37.8) | 0.050 |

| ON-Marg High instability | 8 (36.4) | 31 (42.5) | 10 (27.0) | 0.316 |

| ON-Marg High deprivation | 5 (22.7) | 25 (34.2) | 4 (10.8) | 0.026 |

| ON-Marg High dependency | 9 (40.9) | 43 (58.9) | 18 (48.6) | 0.244 |

| ON-Marg High ethnic concentration | 4 (18.2) | 7 (9.6) | 2 (5.4) | 0.340 |

| No pap within 10 years of dx | 0 (0.0) | 36 (49.3) | 7 (18.9) | <0.001 |

| No pap with 42 months of dx | 1 (4.5) | 68 (93.3) | 14 (37.8) | <0.001 |

| Symptomatic presentation | 4 (18.2) | 52 (71.2) | 27 (73.0) | <0.001 |

| Diagnosed through the ED | 0 (0.0) | 21 (28.8) | 7 (18.9) | 0.006 |

| Stage > 1A | 3 (13.6) | 47 (64.4) | 30 (81.1) | <0.001 |

| Histology: Adenocarcinoma | 8 (36.4) | 17 (23.3) | 8 (21.6) | 0.573 |

| Squamous cell | 12 (54.5) | 52 (71.2) | 26 (70.3) | |

| Other | 2 (9.1) | 4 (5.5) | 3 (8.1) | |

| SCC: Adenocarcinoma ratio | 1.5 | 3.1 | 3.3 | NA |

| Palliative diagnosis | 0 (0.0) | 18 (24.7) | 13 (35.1) | 0.003 |

| Died by 30 June 2024 | 0 (0.0) | 11 (15.1) | 7 (18.9) | 0.075 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Wilkinson, A.N.; Wright, K.; Savage, C.; Pearl, D.; Park, E.; Hopman, W.; Baetz, T. Towards Cervical Cancer Elimination: Insights from an In-Depth Regional Review of Patients with Cervical Cancer. Curr. Oncol. 2026, 33, 52. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol33010052

Wilkinson AN, Wright K, Savage C, Pearl D, Park E, Hopman W, Baetz T. Towards Cervical Cancer Elimination: Insights from an In-Depth Regional Review of Patients with Cervical Cancer. Current Oncology. 2026; 33(1):52. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol33010052

Chicago/Turabian StyleWilkinson, Anna N., Kristin Wright, Colleen Savage, Dana Pearl, Elena Park, Wilma Hopman, and Tara Baetz. 2026. "Towards Cervical Cancer Elimination: Insights from an In-Depth Regional Review of Patients with Cervical Cancer" Current Oncology 33, no. 1: 52. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol33010052

APA StyleWilkinson, A. N., Wright, K., Savage, C., Pearl, D., Park, E., Hopman, W., & Baetz, T. (2026). Towards Cervical Cancer Elimination: Insights from an In-Depth Regional Review of Patients with Cervical Cancer. Current Oncology, 33(1), 52. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol33010052