Prognostic Value of the PET/CT-Derived Maximum Standardized Uptake Value Combined with the Neutrophil–Lymphocyte Ratio in Patients with Hepatocellular Carcinoma Undergoing Hepatectomy

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

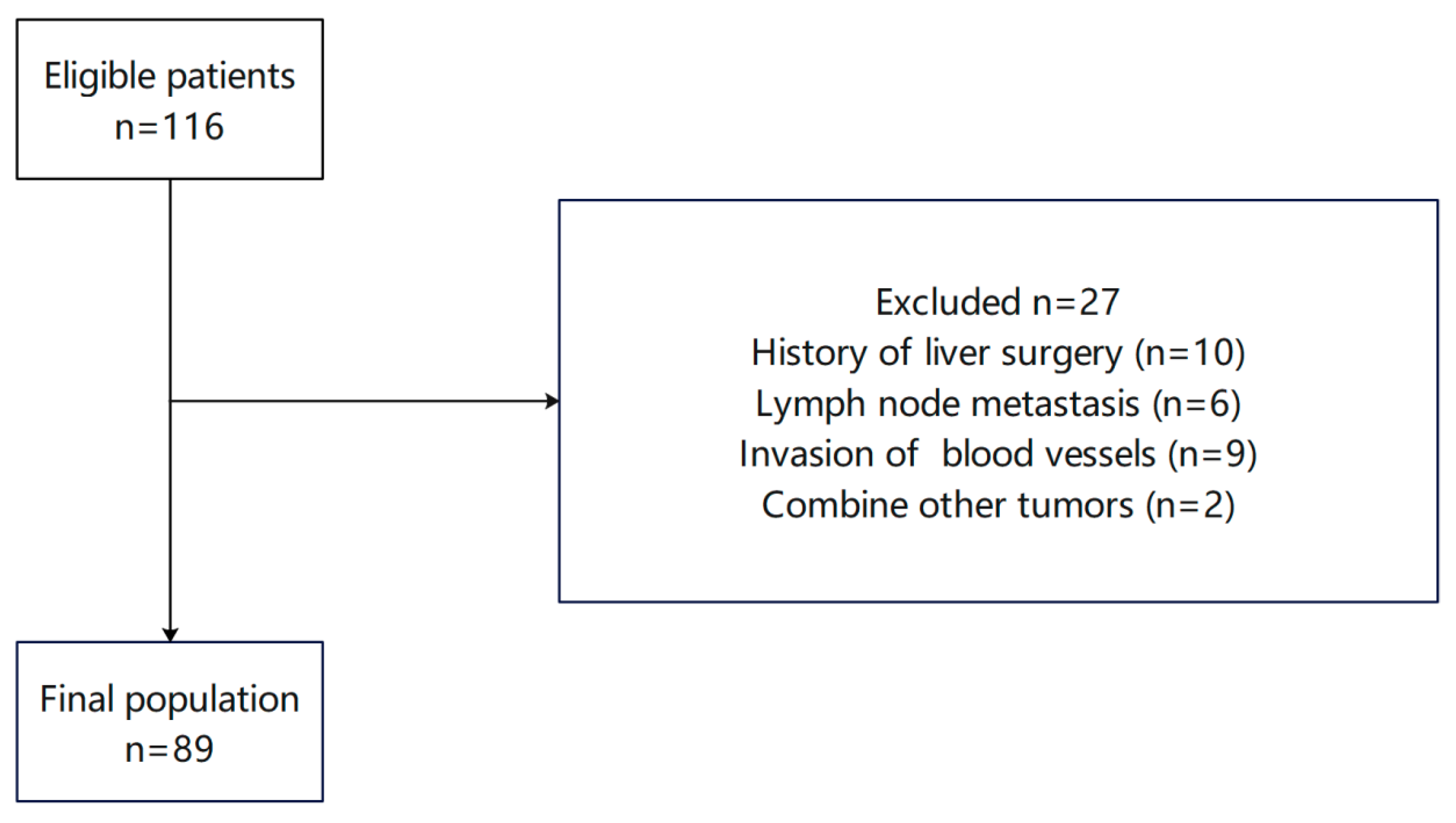

2.1. Case Data and Inclusion/Exclusion Criteria

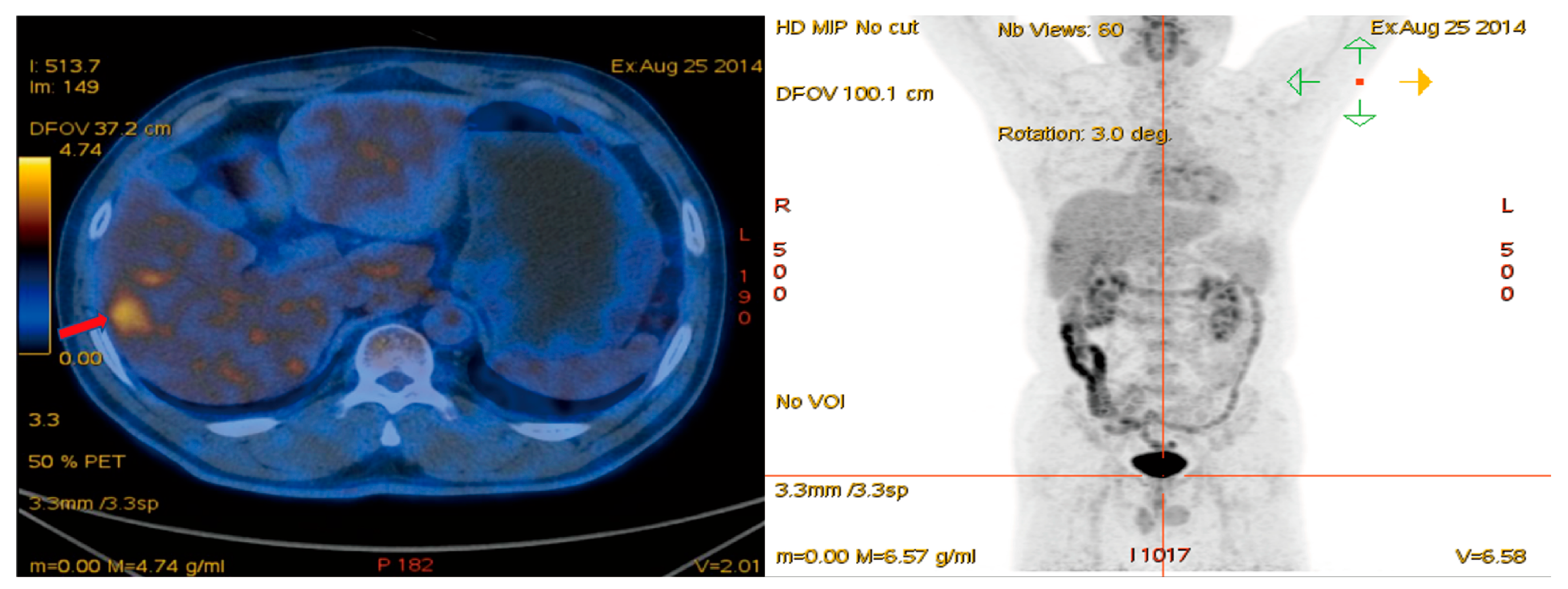

2.2. PET/CT and Research Indicators

2.3. Follow-Up

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Baseline Characteristics of Patients

3.2. Analysis of Correlations Between TLR, NLR, and Tumor Differentiation

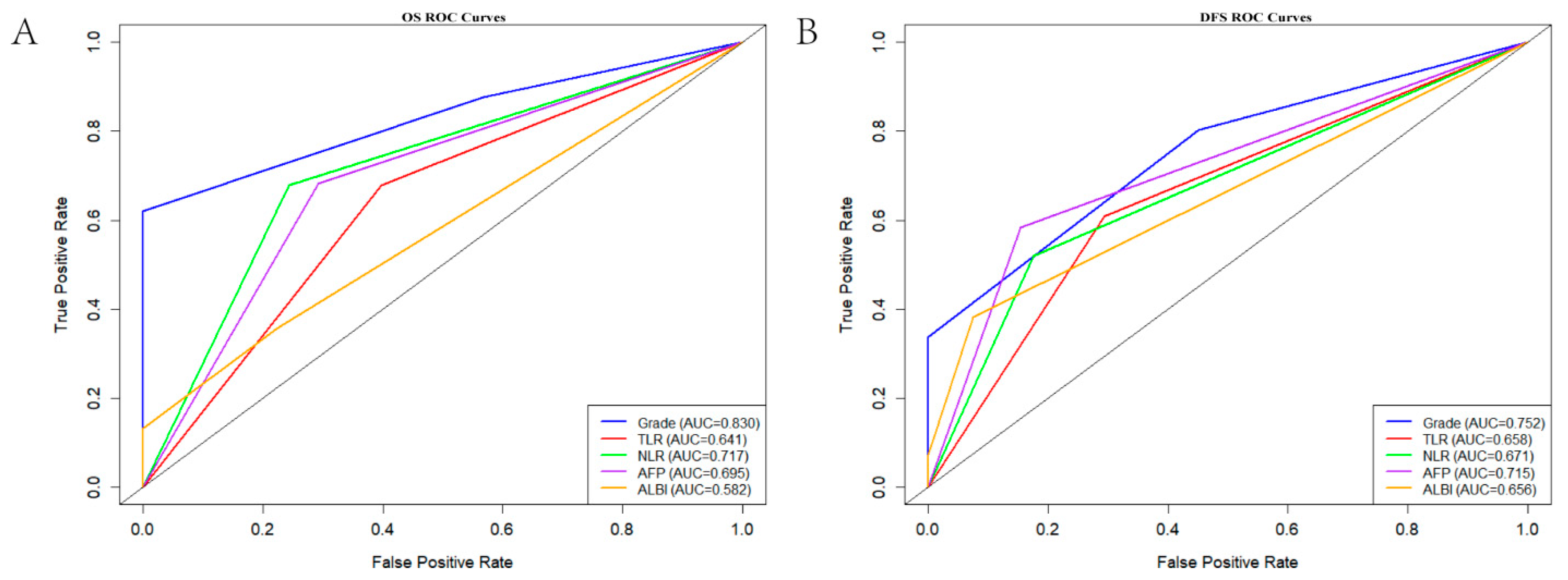

3.3. ROC Curve Analysis

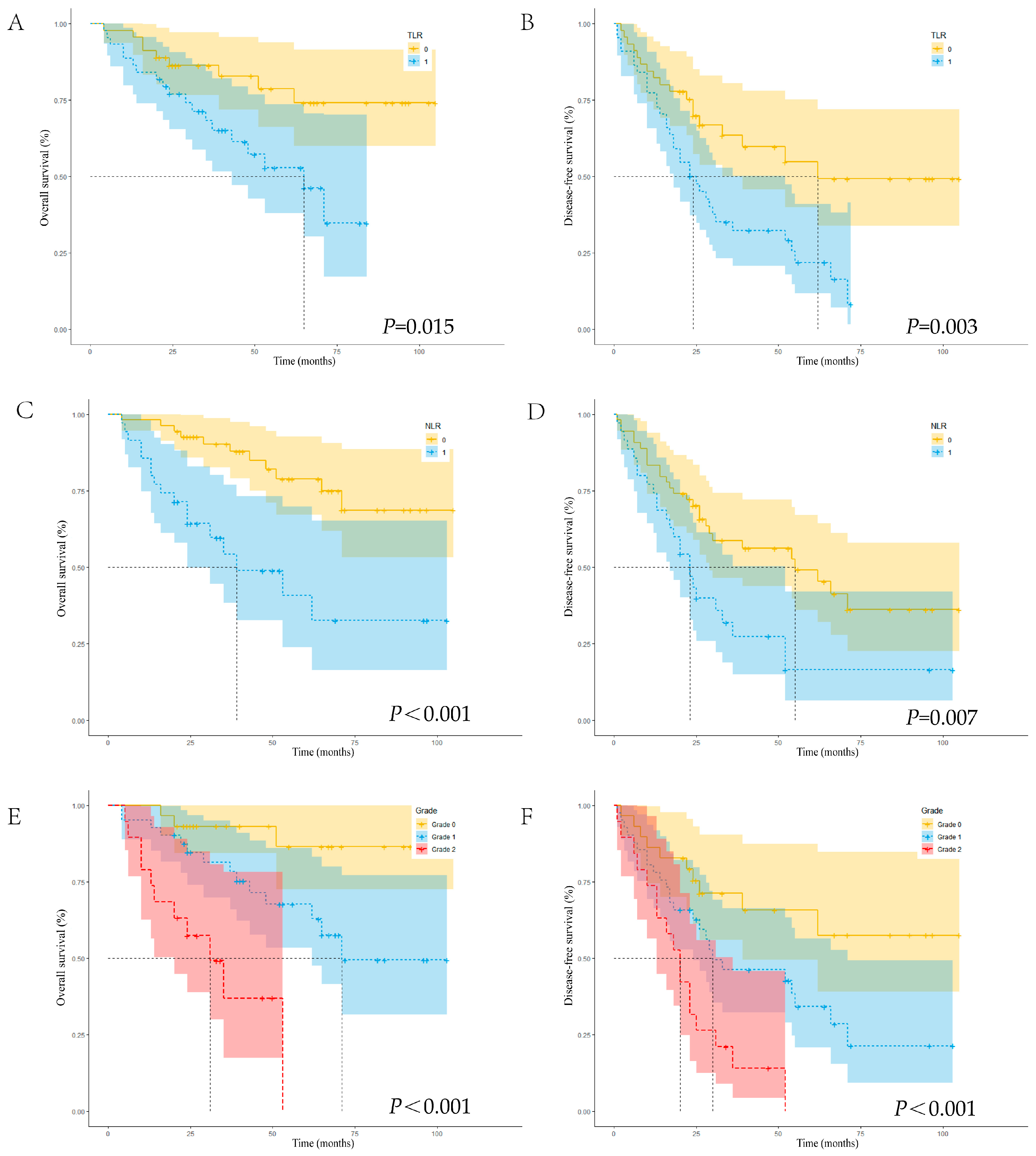

3.4. Cox Regression Analysis and Post-Surgical Survival Curves of OS and DFS

3.5. Assessment of the Performance of the Novel Scoring System for Predicting OS Before Surgery in Patients with HCC

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AFP | Alpha fetoprotein |

| ALBI | Albumin–bilirubin |

| AUC | Area under the curve |

| CI | Confidence interval |

| CT | Computed tomography |

| DFS | Disease-free survival |

| HCC | Hepatocellular carcinoma |

| HR | Hazard ratio |

| LSUVmean | Mean standardized uptake value of liver tissue |

| MASLD | Metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease |

| MELD | Model for End-stage Liver Disease |

| NLR | Neutrophil–lymphocyte ratio |

| OS | Overall survival |

| PET | Positron emission tomography |

| ROC | Receiver operating characteristic |

| SUV | Standardized uptake value |

| SUVmax | Maximum standardized uptake value |

| SUVmean | Mean standardized uptake value |

| TLR | Tumor-to-liver ratio |

| TSUVmax | Maximum standardized uptake value of tumor tissue |

| VIF | Variance inflation factor |

References

- Rumgay, H.; Arnold, M.; Ferlay, J.; Lesi, O.; Cabasag, C.J.; Vignat, J.; Laversanne, M.; McGlynn, K.A.; Soerjomataram, I. Global burden of primary liver cancer in 2020 and predictions to 2040. J. Hepatol. 2022, 77, 1598–1606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GBD 2021 Causes of Death Collaborators. Global burden of 288 causes of death and life expectancy decomposition in 204 countries and territories and 811 subnational locations, 1990–2021: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021. Lancet 2024, 403, 2100–2132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sung, H.; Ferlay, J.; Siegel, R.L.; Laversanne, M.; Soerjomataram, I.; Jemal, A.; Bray, F. Global cancer statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2021, 71, 209–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radosevic, A.; Quesada, R.; Serlavos, C.; Sánchez, J.; Zugazaga, A.; Sierra, A.; Coll, S.; Busto, M.; Aguilar, G.; Flores, D.; et al. Microwave versus radiofrequency ablation for the treatment of liver malignancies: A randomized controlled phase 2 trial. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kudo, M.; Ueshima, K.; Ikeda, M.; Torimura, T.; Tanabe, N.; Aikata, H.; Izumi, N.; Yamasaki, T.; Nojiri, S.; Hino, K.; et al. Randomised, multicentre prospective trial of transarterial chemoembolisation (TACE) plus sorafenib as compared with TACE alone in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma: TACTICS trial. Gut 2020, 69, 1492–1501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gordan, J.D.; Kennedy, E.B.; Abou-Alfa, G.K.; Beal, E.; Finn, R.S.; Gade, T.P.; Goff, L.; Gupta, S.; Guy, J.; Hoang, H.T.; et al. Systemic therapy for advanced hepatocellular carcinoma: ASCO guideline update. J. Clin. Oncol. 2024, 42, 1830–1850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, D.Q.; Singal, A.G.; Kanwal, F.; Lampertico, P.; Buti, M.; Sirlin, C.B.; Nguyen, M.H.; Loomba, R. Hepatocellular carcinoma surveillance—Utilization, barriers and the impact of changing aetiology. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2023, 20, 797–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Liu, L.; Zhang, R.; Hong, J.; Wang, Y.; Wang, J.; Zuo, J.; Zhang, J.; Chen, J.; Hao, H. IL-8 mediates a positive loop connecting increased neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs) and colorectal cancer liver metastasis. J. Cancer 2020, 11, 4384–4396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khandia, R.; Munjal, A. Interplay between inflammation and cancer. Adv. Protein Chem. Struct. Biol. 2020, 119, 199–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eiro, N.; González, L.; Martínez-Ordoñez, A.; Fernandez-Garcia, B.; González, L.O.; Cid, S.; Dominguez, F.; Perez-Fernandez, R.; Vizoso, F.J. Cancer-associated fibroblasts affect breast cancer cell gene expression, invasion and angiogenesis. Cell. Oncol. 2018, 41, 369–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grivennikov, S.I.; Greten, F.R.; Karin, M. Immunity, inflammation, and cancer. Cell 2010, 140, 883–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeNardo, D.G.; Andreu, P.; Coussens, L.M. Interactions between lymphocytes and myeloid cells regulate pro- versus anti-tumor immunity. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2010, 29, 309–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishida, A.; Andoh, A. The Role of Inflammation in Cancer: Mechanisms of Tumor Initiation, Progression, and Metastasis. Cells 2025, 14, 488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geh, D.; Leslie, J.; Rumney, R.; Reeves, H.L.; Bird, T.G.; Mann, D.A. Neutrophils as potential therapeutic targets in hepatocellular carcinoma. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2022, 19, 257–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, K.; Wang, C.; Shi, F.; Huang, Y.; Ma, L.; Li, M.; Song, Y. Combined prognostic value of the SUVmax derived from FDG-PET and the lymphocyte–monocyte ratio in patients with stage IIIB-IV non-small cell lung cancer receiving chemotherapy. BMC Cancer 2021, 21, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, Y.; Oh, D.Y.; Park, H.; Kim, T.Y.; Lee, K.H.; Han, S.W.; Im, S.A.; Kim, T.Y.; Bang, Y.J. More accurate prediction of metastatic pancreatic cancer patients’ survival with prognostic model using both host immunity and tumor metabolic activity. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0145692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Association for the Study of the Liver. EASL Clinical Practice Guidelines: Management of hepatocellular carcinoma. J. Hepatol. 2018, 69, 182–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Wang, H.; Chen, R.; Zhang, H.; Xu, Y.; Zhang, B.; Li, Y.; Zhang, C.; Yang, Y.; Wang, X.; et al. Outcomes and recurrence patterns following curative hepatectomy for hepatocellular carcinoma patients with different China liver cancer staging. Am. J. Cancer Res. 2022, 12, 907–921. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Sun, L.Y.; Cen, W.J.; Tang, W.T.; Deng, L.; Wang, F.; Ji, X.M.; Yang, J.J.; Zhang, R.J.; Zhang, X.H.; Du, Z.M. Alpha–fetoprotein ratio predicts alpha-fetoprotein positive hepatocellular cancer patient prognosis after hepatectomy. Dis. Markers 2022, 2022, 7640560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reig, M.; Forner, A.; Rimola, J.; Ferrer-Fàbrega, J.; Burrel, M.; Garcia-Criado, Á.; Kelley, R.K.; Galle, P.R.; Mazzaferro, V.; Salem, R.; et al. BCLC strategy for prognosis prediction and treatment recommendation: The 2022 update. J. Hepatol. 2022, 76, 681–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, P.J.; Berhane, S.; Kagebayashi, C.; Satomura, S.; Teng, M.; Reeves, H.L.; O’Beirne, J.; Fox, R.; Skowronska, A.; Palmer, D.; et al. Assessment of liver function in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma: A new evidence-based approach-the ALBI grade. J. Clin. Oncol. 2015, 33, 550–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Wang, H.; Yu, S.; Li, X.; Jiang, D.; Wu, Y.; Ren, S.; Qin, L.; Guan, Y.; Lu, L.; et al. Prognostic and diagnostic value of [18F]FDG, 11C-acetate, and [68Ga]Ga-FAPI-04 PET/CT for hepatocellular carcinoma. Eur. Radiol. 2025, 35, 4121–4131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ochi, H.; Hirooka, M.; Hiraoka, A.; Koizumi, Y.; Abe, M.; Sogabe, I.; Ishimaru, Y.; Furuya, K.; Miyagawa, M.; Kawasaki, H.; et al. 18F-FDG-PET/CT predicts the distribution of microsatellite lesions in hepatocellular carcinoma. Mol. Clin. Oncol. 2014, 2, 798–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, R.; Long, X.; Chen, X.; Wang, Y.; Chen, D.; Zhou, R. The Value of Machine Learning-based Radiomics Model Characterized by PET Imaging with 68Ga-FAPI in Assessing Microvascular Invasion of Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Acad. Radiol. 2025, 32, 2233–2246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, X.; Li, Y.; Chao, F.; Mei, X.; Han, X.; Wang, R. Diagnostic significance of fluorine-18-fluorodeoxyglucose-positron emission tomography/computed tomography in differentiating Edmondson grade II and III hepatocellular carcinoma. World J. Gastrointest. Surg. 2025, 17, 107301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, M.J.; Bae, S.H.; Lee, S.W.; Song, D.S.; Kim, H.Y.; Yoo, I.R.; Choi, J.I.; Lee, Y.J.; Chun, H.J.; Lee, H.G.; et al. 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose PET/CT predicts tumour progression after transarterial chemoembolization in hepatocellular carcinoma. Eur. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging 2013, 40, 865–873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hatano, E.; Ikai, I.; Higashi, T.; Teramukai, S.; Torizuka, T.; Saga, T.; Fujii, H.; Shimahara, Y. Preoperative positron emission tomography with fluorine-18-fluorodeoxyglucose is predictive of prognosis in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma after resection. World J. Surg. 2006, 30, 1736–1741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elinav, E.; Nowarski, R.; Thaiss, C.A.; Hu, B.; Jin, C.; Flavell, R.A. Inflammation-induced cancer: Crosstalk between tumours, immune cells and microorganisms. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2013, 13, 759–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, R.; Zhang, Q.; Cao, Q.; Kong, R.; Xiang, X.; Liu, H.; Feng, M.; Wang, F.; Cheng, J.; Li, Z.; et al. Liver tumour immune microenvironment subtypes and neutrophil heterogeneity. Nature 2022, 612, 141–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, S.; Mak, L.; Yuen, M.; Seto, W. Mechanisms of hepatocellular carcinoma and cirrhosis development in concurrent steatotic liver disease and chronic hepatitis B. Clin. Mol. Hepatol. 2025, 31, S182–S195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hung, H.C.; Lee, J.C.; Cheng, C.H.; Wu, T.H.; Wang, Y.C.; Lee, C.F.; Wu, T.J.; Chou, H.S.; Chan, K.M.; Lee, W.C. Impact of neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio on survival for hepatocellular carcinoma after curative resection. J. Hepato-Biliary Pancreat. Sci. 2017, 24, 559–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morand, G.B.; Broglie, M.A.; Schumann, P.; Huellner, M.W.; Rupp, N.J. Histometabolic tumor imaging of hypoxia in oral cancer: Clinicopathological correlation for prediction of an aggressive phenotype. Front. Oncol. 2020, 10, 1670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Werner, J.; Strobel, K.; Lehnick, D.; Rajan, G.P. Overall neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio and SUVmax of nodal metastases predict outcome in head and neck cancer before chemoradiation. Front. Oncol. 2021, 11, 679287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwilas, A.R.; Donahue, R.N.; Tsang, K.Y.; Hodge, J.W. Immune consequences of tyrosine kinase inhibitors that synergize with cancer immunotherapy. Cancer Cell Microenviron. 2015, 2, e677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kubota, R.; Yamada, S.; Kubota, K.; Ishiwata, K.; Tamahashi, N.; Ido, T. Intratumoral distribution of fluorine-18-fluorodeoxyglucose in vivo: High accumulation in macrophages and granulation tissues studied by microautoradiography. J. Nucl. Med. 1992, 33, 1972–1980. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Fuster-Anglada, C.; Mauro, E.; Ferrer-Fàbrega, J.; Caballol, B.; Sanduzzi-Zamparelli, M.; Bruix, J.; Fuster, J.; Reig, M.; Díaz, A.; Forner, A. Histological predictors of aggressive recurrence of hepatocellular carcinoma after liver resection. J. Hepatol. 2024, 81, 995–1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Characteristics | n (%) or Mean ± SD |

|---|---|

| Age (years), mean | 57.40 ± 11.93 |

| Sex (male), n (%) | 71 (79.8) |

| Underlying disease, n (%) | |

| Hepatitis B | 75 (84.3) |

| Hepatitis C | 4 (4.5) |

| Hepatitis B and C | 4 (4.5) |

| Alcohol-related infection | 3 (3.4) |

| Other | 3 (3.4) |

| Cirrhosis | 55 (61.8) |

| MASLD | 14 (15.7) |

| Lymphocyte count (109/L), mean | 1.59 ± 0.61 |

| Platelet count (109/L), mean | 163.55 ± 64.18 |

| Neutrophil count (109/L), mean | 3.19 ± 1.14 |

| Total bilirubin (μmol/L), mean | 15.31 ± 11.32 |

| Albumin (g/L), mean | 41.56 ± 4.85 |

| ALBI grade, mean | −2.81 ± 0.46 |

| TSUVmax, mean | 6.04 ± 3.08 |

| LSUVmean, mean | 2.42 ± 0.47 |

| AFP (ng/mL), mean | 2034.98 ± 8558.89 |

| Tumor size (cm), mean | 5.71 ± 3.54 |

| Number of tumors, mean | 1.24 ± 0.60 |

| Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer stage, n (%) | |

| A | 79 (88.8) |

| B | 10 (11.2) |

| China Liver Cancer stage, n (%) | |

| IA | 41 (46.1) |

| IB | 38 (42.7) |

| IIA | 7 (7.9) |

| IIB | 3 (3.4) |

| Edmondson–Steiner grade, n (%) | |

| Grade I | 24 (26.9) |

| Grade II | 50 (56.2) |

| Grade III | 15 (16.9) |

| Variables | OS | DFS | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Univariate HR (95% CI) | p | Multivariate HR (95% CI) | p | Univariate HR (95% CI) | p | Multivariate HR (95% CI) | p | |

| Age (≥60 years) | 1.981 (0.926–4.239) | 0.078 | 1.562 (0.902–2.707) | 0.112 | ||||

| Sex (male) | 0.568 (0.250–1.292) | 0.177 | 0.475 (0.259–0.871) | 0.016 | 0.647 (0.333–1.258) | 0.199 | ||

| ALBI grade | 0.031 | 0.020 | 0.341 | |||||

| Grade 1 | Reference | Reference | Reference | |||||

| Grade 2 | 0.942 (0.376–2.361) | 0.899 | 0.552 (0.209–1.458) | 0.231 | 1.187 (0.627–2.249) | 0.598 | ||

| Grade 3 | 5.063 (1.470–17.442) | 0.010 | 4.689 (1.268–17.339) | 0.021 | 2.680 (0.808–8.890) | 0.107 | ||

| Viral hepatitis | 0.43 (0.129–1.434) | 0.170 | 0.642 (0.229–1.795) | 0.398 | ||||

| Cirrhosis | 1.208 (0.546–2.676) | 0.641 | 1.133 (0.642–1.997) | 0.667 | ||||

| MASLD | 1.209 (0.490–2.983) | 0.680 | 1.198 (0.615–2.334) | 0.596 | ||||

| NLR (>2.29) | 3.896 (1.802–8.420) | 0.001 | 4.800 (2.045–11.263) | <0.001 | 2.101 (1.206–3.658) | 0.009 | 2.115 (1.155–3.875) | 0.015 |

| TLR (>2.19) | 2.592 (1.167–5.760) | 0.019 | 2.946 (1.281–6.774) | 0.011 | 2.337 (1.315–4.152) | 0.004 | 2.061 (1.106–3.842) | 0.023 |

| AFP (>100 ng/mL) | 3.103 (1.428–6.739) | 0.004 | 2.515 (1.125–5.623) | 0.025 | 2.700 (1.544–4.719) | <0.001 | 2.031 (1.096–3.766) | 0.024 |

| Number of tumors | 1.081 (0.571–2.049) | 0.811 | 1.046 (0.665–1.644) | 0.847 | ||||

| Tumor size (>5 cm) | 1.548 (0.728–3.289) | 0.256 | 1.798 (1.020–3.171) | 0.043 | 1.046 (0.551–1.987) | 0.890 | ||

| Differentiation | 1.321 (0.921–1.894) | 0.130 | 1.054 (0.818–1.358) | 0.686 | ||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Zhou, T.; Dai, C. Prognostic Value of the PET/CT-Derived Maximum Standardized Uptake Value Combined with the Neutrophil–Lymphocyte Ratio in Patients with Hepatocellular Carcinoma Undergoing Hepatectomy. Curr. Oncol. 2026, 33, 13. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol33010013

Zhou T, Dai C. Prognostic Value of the PET/CT-Derived Maximum Standardized Uptake Value Combined with the Neutrophil–Lymphocyte Ratio in Patients with Hepatocellular Carcinoma Undergoing Hepatectomy. Current Oncology. 2026; 33(1):13. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol33010013

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhou, Tianyi, and Chaoliu Dai. 2026. "Prognostic Value of the PET/CT-Derived Maximum Standardized Uptake Value Combined with the Neutrophil–Lymphocyte Ratio in Patients with Hepatocellular Carcinoma Undergoing Hepatectomy" Current Oncology 33, no. 1: 13. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol33010013

APA StyleZhou, T., & Dai, C. (2026). Prognostic Value of the PET/CT-Derived Maximum Standardized Uptake Value Combined with the Neutrophil–Lymphocyte Ratio in Patients with Hepatocellular Carcinoma Undergoing Hepatectomy. Current Oncology, 33(1), 13. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol33010013