Association Between Quality of Discharge Teaching and Post-Discharge Coping Difficulty in Postoperative Lung Cancer Patients: A Chain Mediation Model

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Study Design and Participants

2.2. Measurements and Instruments

2.2.1. Demographic and Disease-Related Data Questionnaire

2.2.2. Post-Discharge Coping Difficulty Scale

2.2.3. Quality of Discharge Teaching Scale

2.2.4. General Self-Efficacy Scale

2.2.5. Readiness for Hospital Discharge Scale

2.3. Procedure

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Participants’ Characteristics

3.2. The Level of Post-Discharge Coping Difficulty

3.3. Correlation Analysis

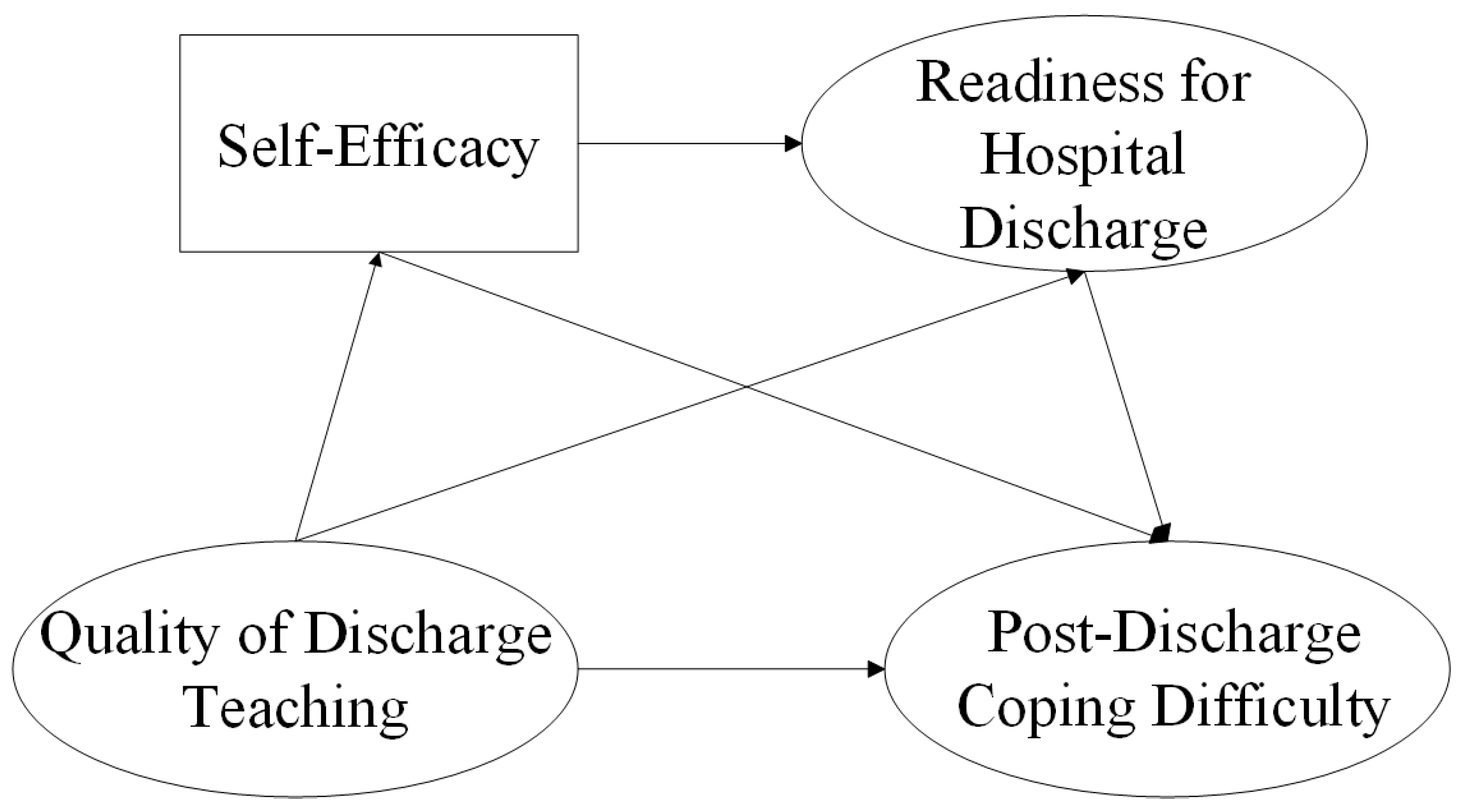

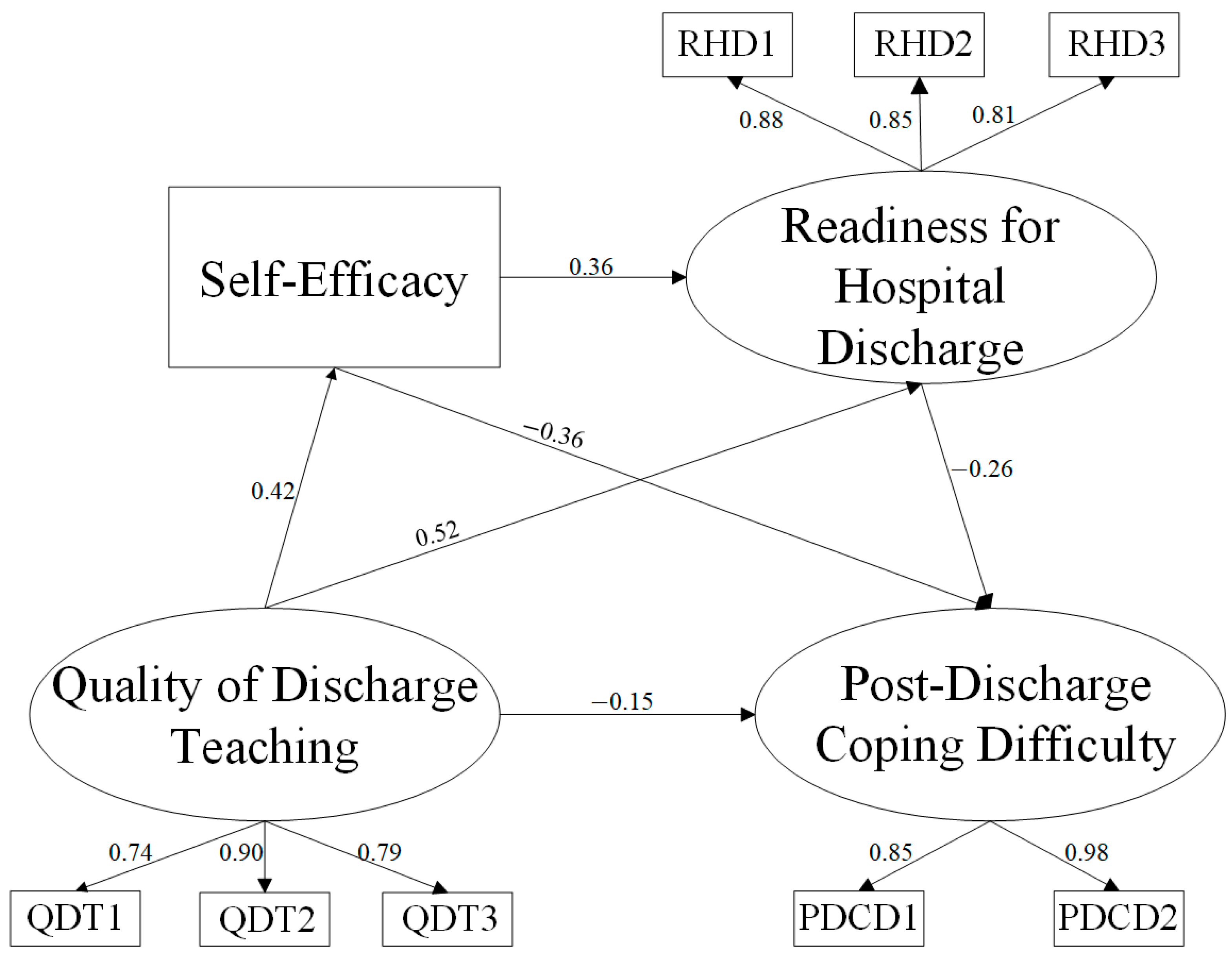

3.4. Structural Equation Model and Mediation Effect Analysis

4. Discussion

4.1. Clinical Implications

4.2. Limitations and Future Direction

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Han, B.; Zheng, R.; Zeng, H.; Wang, S.; Sun, K.; Chen, R.; Li, L.; Wei, W.; He, J. Cancer Incidence and Mortality in China, 2022. J. Natl. Cancer Cent. 2024, 4, 47–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gierada, D.S.; Black, W.C.; Chiles, C.; Pinsky, P.F.; Yankelevitz, D.F. Low-Dose CT Screening for Lung Cancer: Evidence from 2 Decades of Study. Radiol. Imaging Cancer 2020, 2, e190058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johanson, H.; Okereke, I. The Importance of Clinical Decision-Making in Surgical Planning for Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2022, 29, 1509–1510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, A.; Feng, X.; Qiu, C. Discharge Teaching, Readiness for Hospital Discharge and Post-Discharge Outcomes in Cataract Patients: A Structural Equation Model Analysis. J. Nurs. Manag. 2021, 29, 543–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitzgerald Miller, J.; Piacentine, L.B.; Weiss, M. Coping Difficulties After Hospitalization. Clin. Nurs. Res. 2008, 17, 278–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marsall, M.; Hornung, T.; Bäuerle, A.; Weiss, M.E.; Teufel, M.; Weigl, M. Coping Difficulties after Inpatient Hospital Treatment: Validity and Reliability of the German Version of the Post-Discharge Coping Difficulty Scale. J. Patient Rep. Outcomes 2024, 8, 125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Chen, X.; Pan, X.; Tang, X.; Fan, J.; Li, Y. The Unmet Needs of Patients in the Early Rehabilitation Stage after Lung Cancer Surgery: A Qualitative Study Based on Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs Theory. Support. Care Cancer 2023, 31, 677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bouabdallah, I.; Pauly, V.; Viprey, M.; Orleans, V.; Fond, G.; Auquier, P.; D’Journo, X.B.; Boyer, L.; Thomas, P.A. Unplanned Readmission and Survival after Video-Assisted Thoracic Surgery and Open Thoracotomy in Patients with Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer: A 12-Month Nationwide Cohort Study. Eur. J. Cardiothorac. Surg. 2021, 59, 987–995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pu, L.; Dhupar, R.; Meng, X. Predicting Postoperative Lung Cancer Recurrence and Survival Using Cox Proportional Hazards Regression and Machine Learning. Cancers 2025, 17, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, Y. The Impact of the Maternal Quality of Discharge Teaching on Post-Discharge Coping Difficulties: The Chain Mediating Effect of Psychological Resilience and Readiness for Discharge. Master’s Thesis, TUTCM, Tianjin, China, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Chen, R.; Zhang, L.; Li, H.; Gong, Y.; Hang, Y.; Cao, J.; Zhang, H. Relationships Between Quality of Discharge Teaching, Readiness for Hospital Discharge, Self-Efficacy and Self-Management in Patients With First-Episode Stroke: A Cross-Sectional Study. J. Clin. Nurs. 2025, 34, 2830–2839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trivedi, S.P.; Corderman, S.; Berlinberg, E.; Schoenthaler, A.; Horwitz, L.I. Assessment of Patient Education Delivered at Time of Hospital Discharge. JAMA Intern. Med. 2023, 183, 417–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. Self-Efficacy: Toward a Unifying Theory of Behavioral Change. Psychol. Rev. 1977, 84, 191–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Liu, J.; Li, M.; Zhang, H.; Gong, J.; Zhang, J.; Zhu, Y. The Mediating Effects of Parenting Self-Efficacy between Readiness for Hospital Discharge and Post-Discharge Coping Difficulty among Mothers of Preterm Infants. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 19404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Q.; He, L.; Zhong, J.; Zhang, J. Readiness for Hospital Discharge and Its Association with Post-Discharge Outcomes among Oesophageal Cancer Patients after Oesophagectomy: A Prospective Observational Study. J. Clin. Nurs. 2024, 33, 3969–3978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kralik, D.; Visentin, K.; Van Loon, A. Transition: A Literature Review. J. Adv. Nurs. 2006, 55, 320–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meleis, A.I.; Sawyer, L.M.; Im, E.-O.; Hilfinger Messias, D.K.; Schumacher, K. Experiencing Transitions: An Emerging Middle-Range Theory. Adv. Nurs. Sci. 2000, 23, 12–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Elm, E.; Altman, D.G.; Egger, M.; Pocock, S.J.; Gøtzsche, P.C.; Vandenbroucke, J.P. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) Statement: Guidelines for Reporting Observational Studies. Lancet 2007, 370, 1453–1457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, B.; Wang, J. Chinese Medical Association guideline for clinical diagnosis and treatment of lung cancer (2024 edition). Chin. J. Oncol. 2024, 46, 805–843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicolaou, A.I.; Masoner, M.M. Sample Size Requirements in Structural Equation Models under Standard Conditions. Int. J. Acc. Inf. Sy 2013, 14, 256–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Shi, Y.; Wang, J.; Xiang, X.; Xiong, S. The Reliability and Structural Validity of the Chinese Version of the Coping Ability Scale after Discharge. Nurs. Sci. 2021, 10, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiss, M.E.; Piacentine, L.B.; Lokken, L.; Ancona, J.; Archer, J.; Gresser, S.; Holmes, S.B.; Toman, S.; Toy, A.; Vega-Stromberg, T. Perceived Readiness for Hospital Discharge in Adult Medical-Surgical Patients. Clin. Nurse Spec. 2007, 21, 31–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Wang, H.; Yang, C. Reliability and validity of the Chinese version of the Quality of Discharge Teaching Scale. Chin. J. Nurs. 2016, 51, 752–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwarzer, R.; Bäßler, J.; Kwiatek, P.; Schröder, K.; Zhang, J.X. The Assessment of Optimistic Self-Beliefs: Comparison of the German, Spanish, and Chinese Versions of the General Self-Efficacy Scale. Appl. Psychol. 1997, 46, 69–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Hu, Z.; Liu, Y. Evidences for Reliability and Validity of the Chinese Version of General Self-Efficacy Scale. J. Appl. Psychol. 2001, 37–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiss, M.E.; Piacentine, L.B. Psychometric Properties of the Readiness for Hospital Discharge Scale. J. Nurs. Meas. 2006, 14, 163–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.; Gao, J.; Huang, A.; Ji, M.; Zhou, F. Reliability and validity testing of the Chinese version of the Hospital Discharge Preparation Scale. J. Nurs. 2014, 61, 56–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, J.; Li, Z.; He, Y.; Gao, H.; Li, J.; Tao, J. Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Breathing Exercises Effects on Lung Function and Quality of Life in Postoperative Lung Cancer Patients. J. Thorac. Dis. 2024, 16, 4295–4309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williamson, T.J.; Kwon, D.M.; Riley, K.E.; Shen, M.J.; Hamann, H.A.; Ostroff, J.S. Lung Cancer Stigma: Does Smoking History Matter? Ann. Behav. Med. 2020, 54, 535–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Q.; Wang, M.; Liu, F.; Liu, F.; Yue, H.; Cui, J.; Lin, y. Research progress on continuous care for lung cancer patients after surgery. J. Mod. Clin. Med. 2024, 50, 354–356, 360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, J.; Shukla, H.S. Trajectories of Depression, Anxiety, and Stress among Breast Cancer Patients: Assessment at 1st Year of Diagnosis. Indian. J. Palliat. Care 2025, 31, 192–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freak-Poli, R.; Htun, H.L.; Teshale, A.B.; Kung, C. Understanding Loneliness after Widowhood: The Role of Social Isolation, Social Support, Self-Efficacy, and Health-Related Factors. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2025, 129, 105692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, J.; Du, S.; Dong, X. Associations of Education Level With Survival Outcomes and Treatment Receipt in Patients With Gastric Adenocarcinoma. Front. Public. Health 2022, 10, 868416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enogieru, I.; Osazuwa-Peters, O.L.; Vin-Raviv, N.; Wang, F.; Benitez, J.A.; Akinyemiju, T. Racial and Ethnic Differences in 60-Day Hospital Readmissions for Patients with Breast, Colorectal, Lung, and Prostate Cancer. J. Racial Ethn. Health Disparities 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saw, S.P.L.; Ong, B.-H.; Chua, K.L.M.; Takano, A.; Tan, D.S.W. Revisiting Neoadjuvant Therapy in Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer. Lancet Oncol. 2021, 22, e501–e516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, J.; Huang, T.; Xu, J.; Xiao, J.; Chen, Q.; Zhang, L. Effect of Nursing Method of Psychological Intervention Combined with Health Education on Lung Cancer Patients Undergoing Chemotherapy. J. Healthc. Eng. 2022, 2022, 2438612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variables | Groups | N (%) | t/F | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | Female | 184 (51.4) | 33.65 ± 10.27 | 0.708 | 0.401 |

| Male | 174 (48.6) | 35.03 ± 9.69 | |||

| Age | 18–40 | 35 (9.8) | 25.86 ± 9.63 | 19.018 | <0.001 |

| 41–65 | 223 (62.3) | 34.27 ± 9.40 | |||

| ≥66 | 100 (27.9) | 37.40 ± 9.79 | |||

| Marital status | Unmarried | 15 (4.2) | 26.73 ± 10.16 | 6.243 | 0.002 |

| Married | 310 (86.6) | 34.35 ± 9.82 | |||

| Divorced or widowed | 33 (9.2) | 37.58 ± 10.05 | |||

| Educational degree | Primary or below | 134 (37.4) | 36.93 ± 9.33 | 13.486 | <0.001 |

| Junior or senior high school | 172 (48.0) | 33.97 ± 9.78 | |||

| College or above | 52 (14.5) | 28.79 ± 10.15 | |||

| Employment | Employed | 204 (57.0) | 33.64 ± 10.70 | 1.354 | 0.259 |

| Retired | 80 (22.3) | 35.78 ± 10.03 | |||

| Unemployed | 74 (20.7) | 34.64 ± 7.64 | |||

| Living alone | Yes | 59 (16.5) | 35.54 ± 10.54 | 1.342 | 0.247 |

| No | 299 (83.5) | 34.08 ± 9.89 | |||

| Monthly household income | ≤CNY 2000 (a) | 15 (4.2) | 39.73 ± 11.05 | 3.248 | 0.022 |

| CNY 2001–4000 (b) | 116 (32.4) | 35.53 ± 9.51 | |||

| CNY 4001–6000 (c) | 114 (31.8) | 34.12 ± 9.81 | |||

| ≥CNY 6001 (d) | 113 (31.6) | 32.58 ± 10.25 | |||

| Type of medical insurance | URRBMI | 227 (63.4) | 34.86 ± 9.92 | 0.639 | 0.424 |

| UEBMI | 131 (36.6) | 33.40 ± 10.12 | |||

| Primary caregiver | Family caregiver | 314 (87.7) | 33.87 ± 9.83 | 0.957 | 0.329 |

| Care worker or without a caregiver | 44 (12.3) | 37.55 ± 10.66 | |||

| Postoperative length of stay | ≤5 days | 254 (70.9) | 33.59 ± 9.90 | 0.037 | 0.849 |

| ≥6 days | 104 (29.1) | 36.13 ± 10.08 | |||

| Pain score at discharge | 0 | 162 (45.3) | 34.01 ± 10.54 | 0.195 | 0.823 |

| 1 | 91 (25.4) | 34.35 ± 9.99 | |||

| 2 | 105 (29.3) | 34.79 ± 9.21 | |||

| TNM staging | I | 112 (31.3) | 28.92 ± 9.78 | 46.104 | <0.001 |

| II | 172 (48.0) | 34.65 ± 8.44 | |||

| III | 74 (20.7) | 41.74 ± 8.73 | |||

| Occurrence of pre-discharge complications | Yes | 29 (8.1) | 34.72 ± 10.01 | 0.000 | 0.991 |

| No | 329 (91.9) | 34.29 ± 10.02 |

| Item | Average Score () | Affiliated Dimension |

|---|---|---|

| 1. How would you describe your current level of life stress? | 4.48 ± 1.51 | emotional management |

| 2. What difficulties have you encountered during your recovery process? | 4.59 ± 1.62 | emotional management |

| 3. What challenges have you faced while taking care of yourself? | 4.87 ± 1.76 | living management |

| 4. What obstacles have you experienced in the treatment of your illness? (For example: financial issues, choices in medical care, effectiveness of recovery, etc.) | 4.82 ± 1.66 | living management |

| 5. What difficulties have your relatives or other close individuals felt during your discharge from the hospital? | 4.94 ± 1.62 | living management |

| 6. To what extent do you require assistance to take care of yourself adequately? | 4.92 ± 1.78 | living management |

| 7. What level of emotional support do you need during this period of your discharge from the hospital? | 5.71 ± 1.91 | living management |

| QDT | QDT1 | QDT2 | QDT3 | GSE | RHD | RHD1 | RHD2 | RHD3 | PDCD | PDCD1 | PDCD2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| QDT | 1 | |||||||||||

| QDT1 | 0.865 ** | 1 | ||||||||||

| QDT2 | 0.886 ** | 0.724 ** | 1 | |||||||||

| QDT3 | 0.878 ** | 0.601 ** | 0.690 ** | 1 | ||||||||

| GSE | 0.399 ** | 0.285 ** | 0.323 ** | 0.429 ** | 1 | |||||||

| RHD | 0.568 ** | 0.448 ** | 0.482 ** | 0.564 ** | 0.523 ** | 1 | ||||||

| RHD1 | 0.556 ** | 0.438 ** | 0.485 ** | 0.537 ** | 0.498 ** | 0.863 ** | 1 | |||||

| RHD2 | 0.459 ** | 0.364 ** | 0.392 ** | 0.462 ** | 0.475 ** | 0.904 ** | 0.697 ** | 1 | ||||

| RHD3 | 0.523 ** | 0.414 ** | 0.429 ** | 0.526 ** | 0.442 ** | 0.857 ** | 0.640 ** | 0.661 ** | 1 | |||

| PDCD | −0.447 ** | −0.349 ** | −0.392 ** | −0.433 ** | −0.575 ** | −0.522 ** | −0.474 ** | −0.475 ** | −0.469 ** | 1 | ||

| PDCD1 | −0.379 ** | −0.303 ** | −0.343 ** | −0.363 ** | −0.477 ** | −0.474 ** | −0.423 ** | −0.437 ** | −0.426 ** | 0.906 ** | 1 | |

| PDCD2 | −0.446 ** | −0.348 ** | −0.386 ** | −0.434 ** | −0.581 ** | −0.514 ** | −0.470 ** | −0.468 ** | −0.460 ** | 0.985 ** | 0.822 ** | 1 |

| β | SE | Bias-Corrected95% | p | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | ||||

| Standardized Direct Effect | |||||

| QDTS→PDCDS | −0.154 | 0.076 | −0.307 | −0.001 | <0.05 |

| QDTS→GSES | 0.420 | 0.051 | 0.315 | 0.516 | <0.001 |

| QDTS→RHDS | 0.520 | 0.058 | 0.406 | 0.631 | <0.001 |

| GSES→RHDS | 0.361 | 0.054 | 0.248 | 0.460 | <0.001 |

| GSES→PDCDS | −0.356 | 0.051 | −0.449 | −0.246 | 0.001 |

| RHDS→PDCDS | −0.264 | 0.084 | −0.434 | −0.102 | <0.05 |

| Standardized Indirect Effect | |||||

| QDTS→GSES→PDCDS | −0.150 | 0.028 | −0.208 | −0.098 | <0.001 |

| QDTS→RHDS→PDCDS | −0.137 | 0.048 | −0.252 | −0.057 | 0.001 |

| QDTS→GSES→RHDS→PDCDS | −0.040 | 0.014 | −0.073 | −0.017 | 0.001 |

| Standardized Total indirect effect | −0.327 | 0.060 | −0.469 | −0.226 | <0.001 |

| Standardized Total Effect | −0.481 | 0.049 | −0.574 | −0.382 | <0.001 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wang, M.; Tu, H.; Hong, J. Association Between Quality of Discharge Teaching and Post-Discharge Coping Difficulty in Postoperative Lung Cancer Patients: A Chain Mediation Model. Curr. Oncol. 2025, 32, 468. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol32080468

Wang M, Tu H, Hong J. Association Between Quality of Discharge Teaching and Post-Discharge Coping Difficulty in Postoperative Lung Cancer Patients: A Chain Mediation Model. Current Oncology. 2025; 32(8):468. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol32080468

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Minghui, Hailing Tu, and Jingfang Hong. 2025. "Association Between Quality of Discharge Teaching and Post-Discharge Coping Difficulty in Postoperative Lung Cancer Patients: A Chain Mediation Model" Current Oncology 32, no. 8: 468. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol32080468

APA StyleWang, M., Tu, H., & Hong, J. (2025). Association Between Quality of Discharge Teaching and Post-Discharge Coping Difficulty in Postoperative Lung Cancer Patients: A Chain Mediation Model. Current Oncology, 32(8), 468. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol32080468