Atypical Cystic Primary Hepatic GIST: A Case Report of Rare Presentation and Long-Term Survival

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Case Report

2.1. Timeline Presentation

- Month 0

- Diagnosis of primary hepatic gastrointestinal stromal tumour (PHGIST).

- Month 1

- First surgical intervention to confirm diagnosis and perform reductive tumourectomy.

- Month 3

- Initiation of first-line treatment with imatinib (400 mg/day).

- Month 64

- Second surgical intervention for cystic tumour in the left hepatic lobe, followed by third surgical intervention involving atypical segment III hepatectomy.

- Month 65

- Initiation of second-line treatment with sunitinib (50 mg/day).

- Month 72

- CT evaluation shows stable hepatic disease; side effects noted.

- Month 85

- New cystic lesion detected in segment VII, raising concerns about treatment resistance.

- Month 96

- Patient’s death recorded, 8 years post-diagnosis.

2.2. Initial Diagnosis

2.3. First Surgical Intervention

- Segment VII: Two target-like (bull’s-eye) images with a hypoechoic/transonic peripheral rim and a heterogeneous hyperechoic central zone, with maximum diameters of 3.1 cm and 1.8 cm.

- Portal vein: Measured 8 mm; the common bile duct (CBD) was 5 mm with heterogeneous content.

- Gallbladder: Compressed gallbladder, non-identifiable.

- Peripheral hepatic parenchyma: Exhibited steatosis.

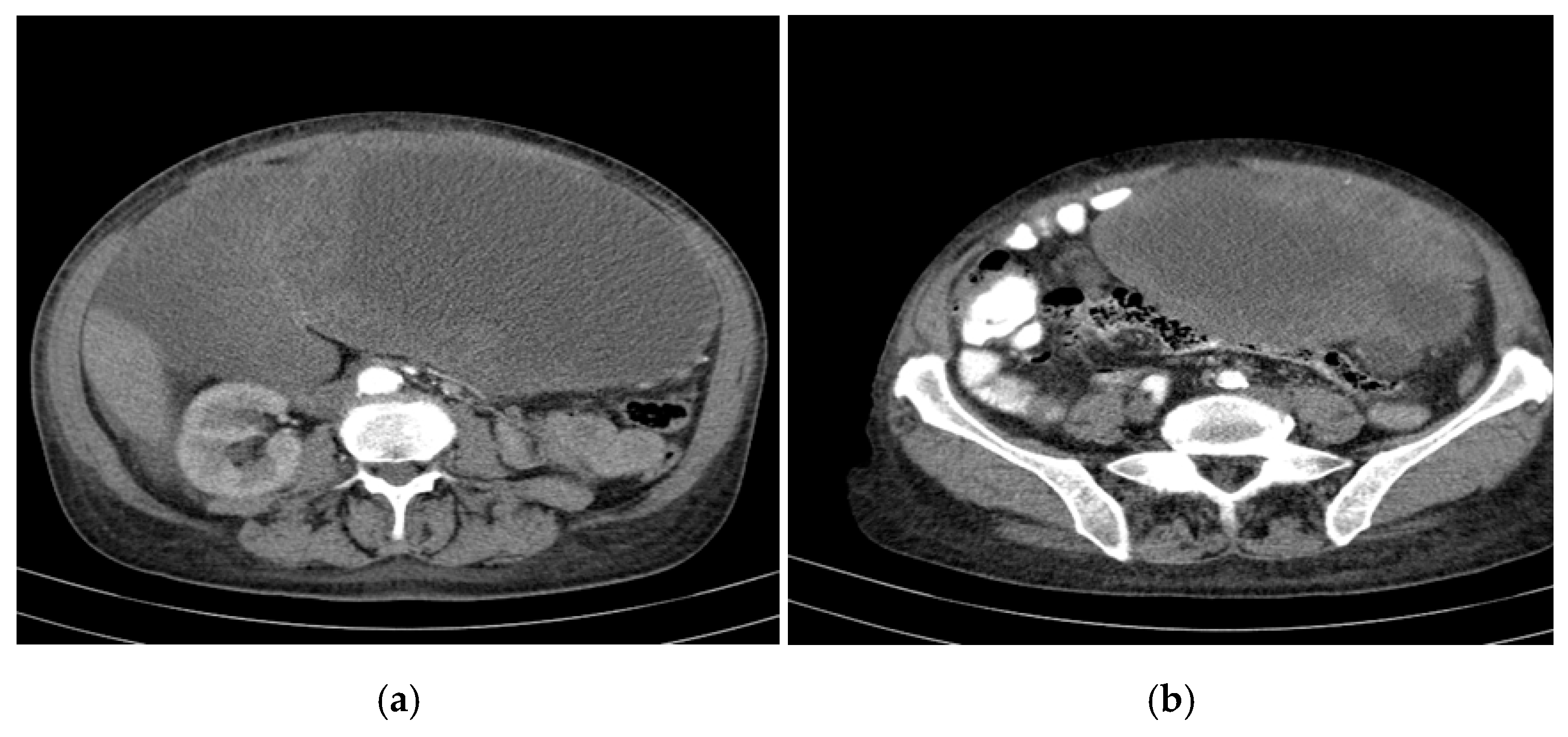

- Large cystic formations: Occupying the right hypochondrium and flank, epigastrium, left hypochondrium, and left flank, with a transonic appearance, thickened heterogeneous wall (up to 3 cm), and irregular hyperechoic septations, some possibly vascularized.

- Largest transonic formation: Located in the left abdomen with a heterogeneous circumferential wall (up to 8.3 in thickness); contained heterogeneous fluid with multiple echogenic/hyperechoic echoes, which were mobile upon compression (Figure 2).

2.4. Histopathological Examination

2.5. Immunohistochemical Analysis

- CD117, VIMENTIN, PDGFR-Alpha, CD34, DOG1—Positive in tumour cells.

- ACTININ—Negative in tumour cells, positive in blood vessels.

- Ki67—Positive, with a proliferation index of 25% in tumour cells.

- S100—Negative.

2.6. First-Line Treatment with Imatinib (Total Duration: 55 Months)

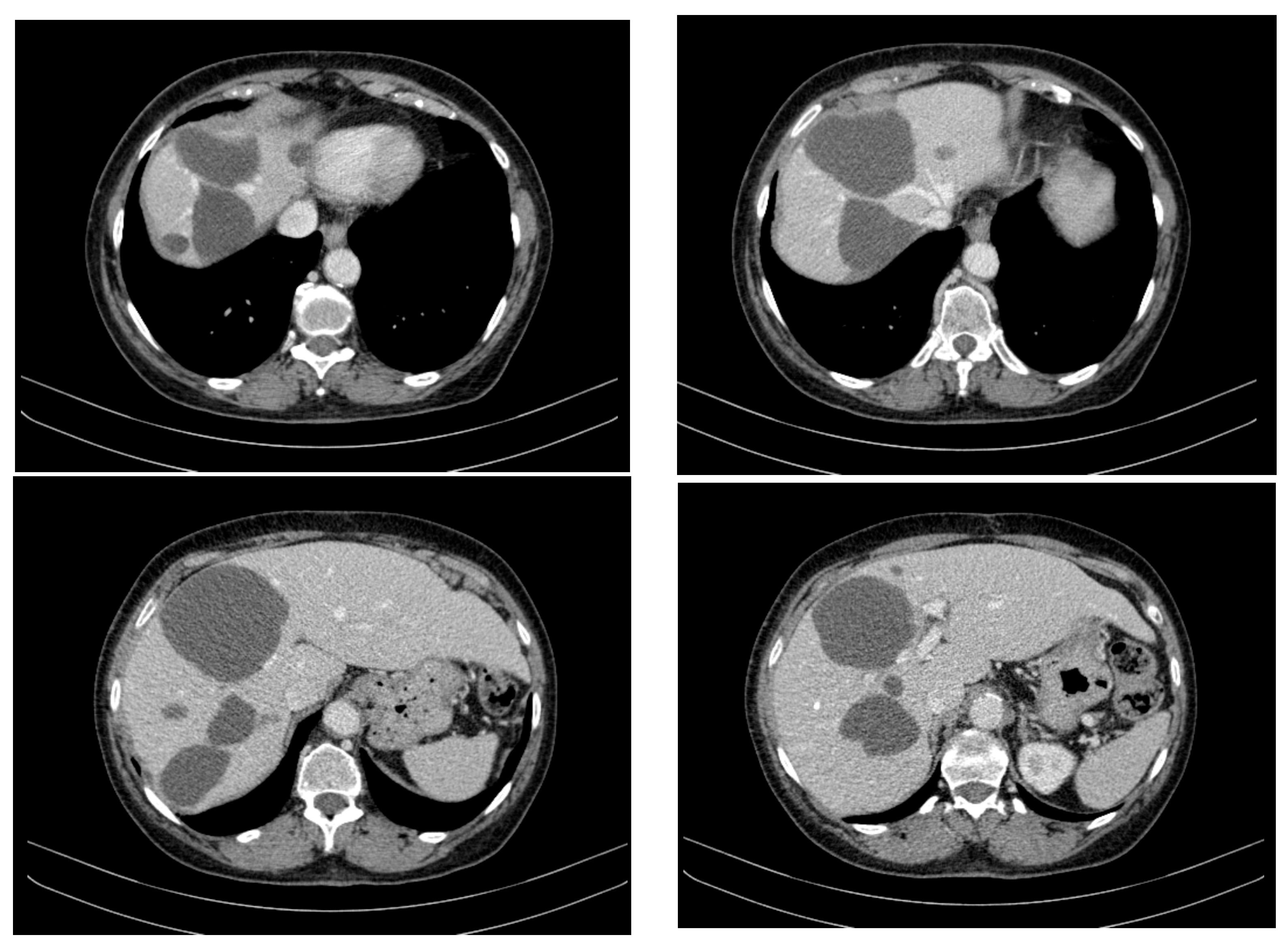

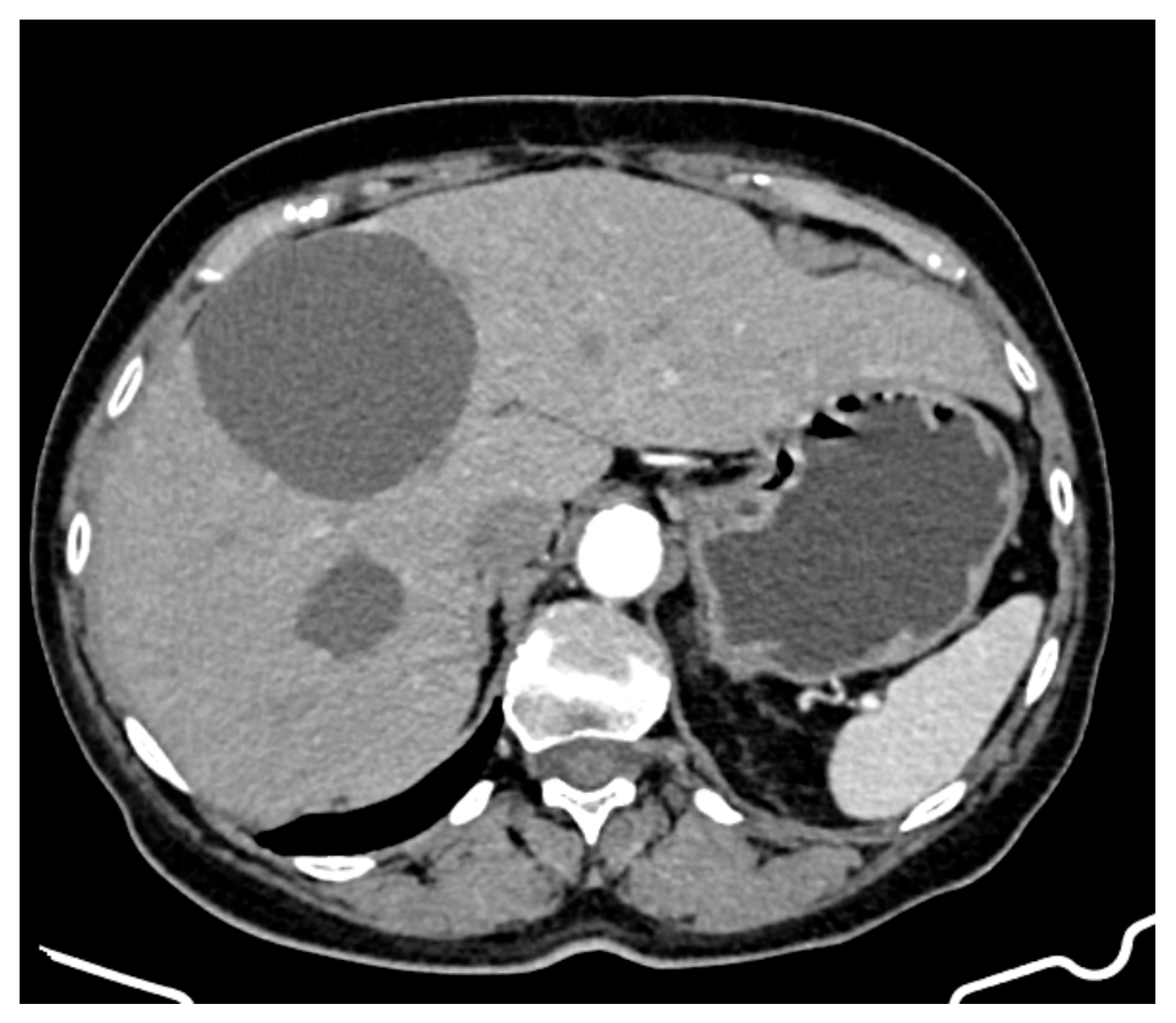

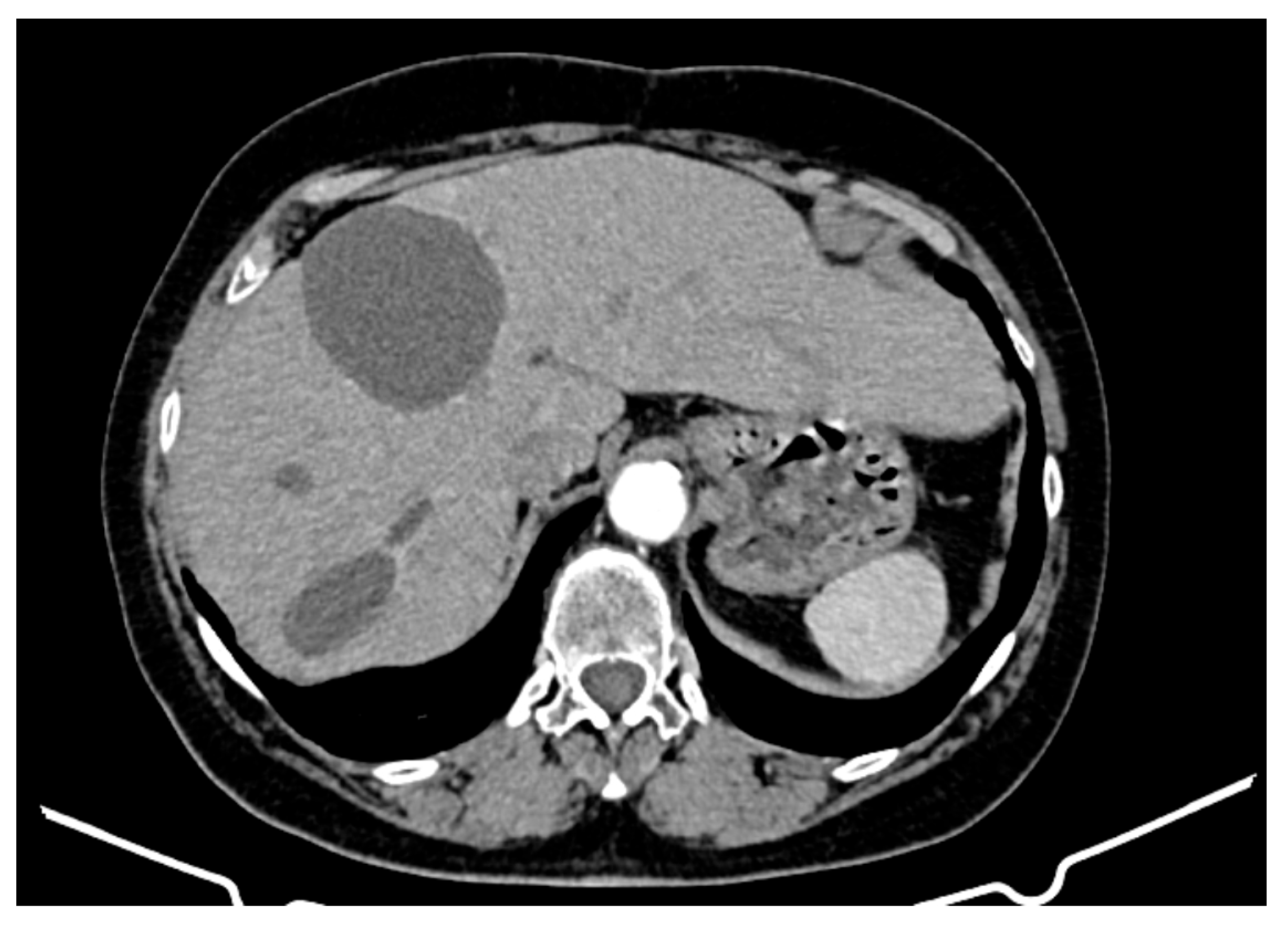

- Hepatic tumour stability: Multiple large cystic hepatic lesions remained stable in size throughout the monitoring period, with no significant new secondary lesions developing. The largest hepatic cystic tumours persisted in segments IV, VI, and VIII, with maximum dimensions of ~8 cm, without major structural changes.

- Regression of extrahepatic lesions: Initial gastric and peritoneal lesions, including a cystic formation in the anterior gastric wall and ascitic fluid, regressed significantly by month 14 and did not reappear in later scans. The left inguinal hernia, although noted consistently, remained unchanged, without complications.

- Emergence of new findings without aggressive progression: A subcapsular nodule (3.5 × 2 cm) in Morrison’s space was identified during month 41, remaining stable without concerning enhancement patterns. A pseudo-nodular perfusion anomaly in segment VIII was noted but was attributed to pressure from the large cystic tumour rather than neoplastic progression. Mild gastric antral wall thickening developed later (by month 49), with a maximum thickness of 14 mm, but remained stable thereafter, with no associated adenopathy or signs of malignant transformation.

- Absence of significant distant metastases or new systemic involvement: Throughout the entire monitoring period, there were no newly detected secondary metastatic lesions in the thoracic, abdominal, or pelvic regions; no significant adenopathy was identified; and there was no recurrence of ascitic fluid beyond a mild amount in the early monitoring phases.

- New large cystic tumour formation;

- Previously known lesions remaining stable;

- An absence of metastatic progression.

2.7. Second Surgical Intervention

2.8. Third Surgical Intervention

2.9. Second-Line Treatment with Sunitinib (Total Duration: 30 Months)

2.10. Summary of Clinical–Pathological Data

- Initial Presentation

- Age: At diagnosis, 71.5 years.

- Symptoms: Loss of appetite, fatigue, weight loss, abdominal pain, dyspnoea, cough.

- Biochemical Evaluation: Moderate anaemia, thrombocytosis, mild hepatic cytolysis, anicteric cholestasis syndrome, significant inflammatory syndrome.

- Imaging: Abdominopelvic CT showed numerous cystic liver lesions (1 cm to 18 cm), mostly in the right hepatic lobe. Largest cysts in segments IVb and III of the left hepatic lobe.

- First Surgical Intervention

- Findings: Large cystic formations with a transonic appearance and thickened heterogeneous walls. Portal vein measured 8 mm; CBD 5 mm with heterogeneous content.

- Histopathology: Spindle cells with vacuolated cytoplasm and oval nuclei. Low mitotic activity (3 mitoses/50 HPF).

- Immunohistochemistry: Positive for CD117, VIMENTIN, PDGFR-Alpha, CD34, and DOG1; Ki67 proliferation index of 25%.

- Treatment with Imatinib (55 months)

- Dosage: 400 mg/day.

- Response: Rapid improvement, reduced drainage, stable disease course with partial regression of lesions.

- Side Effects: Muscle spasms, sporadic vomiting.

- Second Surgical Intervention

- Procedure: Addressed cystic tumour in the left hepatic lobe.

- Third Surgical Intervention

- Procedure: Atypical segment III hepatectomy for a large cystic tumour.

- Treatment with Sunitinib (30 months)

- Side Effects: Hypertension, neutropenia, nail bed dekeratinization in all toes, alopecia, persistent anaemia.

- Disease Progression and Outcome

- Survival: Eight years post-diagnosis.

- Final Symptoms: Abdominal distension, pain, paraesthesia in limbs.

2.11. Disease Progression and Outcome

3. Discussion

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CBD | Common bile duct |

| CT | Computer tomograph |

| GIST | Gastrointestinal stromal tumour |

| IHC | Immunohistochemistry |

| PHGIST | Primary hepatic gastrointestinal stromal tumour |

| TKIs | Tyrosine kinase inhibitors |

References

- Becker, E.C.; Ozcan, G.; Wu, G.Y. Primary Hepatic Extra-gastrointestinal Stromal Tumors: Molecular Pathogenesis, Immunohistopathology, and Treatment. J. Clin. Transl. Hepatol. 2023, 11, 942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holthuis, E.I.; Slijkhuis, V.; van der Graaf, W.T.A.; Drabbe, C.; van Houdt, W.J.; Schrage, Y.M.; Olde Hartman, T.C.; Uijen, A.; Steeghs, N.; Bos, I.; et al. The Prediagnostic General Practitioners’ Pathway of Gastrointestinal Stromal Tumor Patients: A Real-World Data Study. Cancers 2025, 17, 1391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manuel-Vázquez, A.; Latorre-Fragua, R.; de la Plaza-Llamas, R.; Ramia, J.M. Hepatic gastrointestinal stromal tumor: Systematic review of an exceptional location. World J. Meta Anal. 2019, 7, 224–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Tian, Y.; Liu, S.; Xu, G.; Guo, M.; Lian, X.; Fan, D.; Zhang, H.; Feng, F. Clinicopathological feature and prognosis of primary hepatic gastrointestinal stromal tumor. Cancer Med. 2016, 5, 2268–2275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matsumoto, K.; Terao, Y.; Hoshino, T. Advanced imaging techniques for the evaluation of gastrointestinal stromal tumors: A review of current practices and future directions. Eur. J. Radiol. 2023, 154, 110449. [Google Scholar]

- Nishida, T.; Blay, J.-Y.; Hirota, S.; Kitagawa, Y.; Kang, Y.-K.; Nishida, T.; Blay, J.-Y.; Hirota, S.; Kitagawa, Y.; Kang, Y.-K. The standard diagnosis, treatment, and follow-up of gastrointestinal stromal tumors based on guidelines. Gastric Cancer 2015, 19, 3–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qian, X.-H.; Yan, Y.-C.; Gao, B.-Q.; Wang, W.-L. Prevalence, diagnosis, and treatment of primary hepatic gastrointestinal stromal tumors. World J. Gastroenterol. 2020, 26, 6195–6206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, Y. The role of neoadjuvant and adjuvant therapies in the management of gastrointestinal stromal tumors: A comprehensive review. Oncol. Rep. 2023, 49, 32–40. [Google Scholar]

- Rîmbu, M.C.; Popescu, L.; Mihăilă, M.; Sandulovici, R.C.; Cord, D.; Mihăilescu, C.-M.; Gălățanu, M.L.; Panțuroiu, M.; Manea, C.-E.; Boldeiu, A.; et al. Synergistic Effects of Green Nanoparticles on Antitumor Drug Efficacy in Hepatocellular Cancer. Biomedicines 2025, 13, 641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Béchade, D. Clinical Utility of Endoscopic Ultrasound (EUS) and Endobronchial Ultrasound (EBUS) in the Evaluation of Mediastinal Lymphadenopathy. Diagnostics 2025, 15, 349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Demetri, G.D.; Reichardt, P.; Kang, Y.-K.; Blay, J.-Y.; Rutkowski, P.; Gelderblom, H.; Hohenberger, P.; Leahy, M.; Mehren, M.v.; Joensuu, H.; et al. Efficacy and safety of regorafenib for advanced gastrointestinal stromal tumours after failure of imatinib and sunitinib (GRID): An international, multicentre, randomised, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet 2013, 381, 295–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joensuu, H.; Wardelmann, E.; Sihto, H.; Eriksson, M.; Hall, K.S.; Reichardt, A.; Hartmann, J.T.; Pink, D.; Cameron, S.; Hohenberger, P.; et al. KIT and PDGFRA Mutations in Patients With Gastrointestinal Stromal Tumor. JAMA Oncol. 2017, 3, 602–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohammadi, M.; Roets, E.; Bleckman, R.F.; Oosten, A.W.; Grunhagen, D.; Desar, I.M.E.; Bonenkamp, H.; Reyners, A.K.L.; van Etten, B.; Hartgrink, H.; et al. Impact of Mutation Profile on Outcomes of Neoadjuvant Therapy in GIST. Cancers 2025, 17, 634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schöffski, P.; Reichardt, P.; Blay, J.Y.; Dumez, H.; Morgan, J.A.; Ray-Coquard, I.; Hollaender, N.; Jappe, A.; Demetri, G.D. A phase I-II study of everolimus (RAD001) in combination with imatinib in patients with imatinib-resistant gastrointestinal stromal tumors. Ann. Oncol. 2010, 21, 1990–1998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Catalano, F.; Cremante, M.; Dalmasso, B.; Pirrone, C.; Lagodin D’Amato, A.; Grassi, M.; Comandini, D. Molecular Tailored Therapeutic Options for Advanced Gastrointestinal Stromal Tumors (GISTs): Current Practice and Future Perspectives. Cancers 2023, 15, 2074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Demetri, G.D.; Oosterom, A.T.v.; Garrett, C.R.; Blackstein, M.E.; Shah, M.H.; Verweij, J.; McArthur, G.; Judson, I.R.; Heinrich, M.C.; Morgan, J.A.; et al. Efficacy and safety of sunitinib in patients with advanced gastrointestinal stromal tumour after failure of imatinib: A randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2006, 368, 1329–1338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Handra, C.M.; Chirila, M.; Smarandescu, R.A.; Ghita, I. Near Missed Case of Occupational Pleural Malignant Mesothelioma, a Case Report and Latest Therapeutic Options. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 14763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ryu, M.H.; Kim, S.H. Surgical Management of Gastrointestinal Stromal Tumors: A Review of Current Evidence. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2020, 27, 2290–2296. [Google Scholar]

- Ran, P.; Zhou, H.; Li, J.; Tan, T.; Yang, H.; Li, J.; Zhang, J. Improving Outcomes in the Advanced Gastrointestinal Stromal Tumors: The Role of the Multidisciplinary Team Discussion Intervention. J. Pers. Med. 2023, 13, 417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cicala, C.M.; Bauer, S.; Heinrich, M.C.; Serrano, C. Gastrointestinal Stromal Tumor: Current Approaches and Future Directions in the Treatment of Advanced Disease. Hematol. Oncol. Clin. N. Am. 2025, 39, 773–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rimbu, M.C.; Ungureanu, F.D.; Moldovan, C.; Toba, M.E.; Chirila, M.; Truta, E.; Cord, D. Atypical Cystic Primary Hepatic GIST: A Case Report of Rare Presentation and Long-Term Survival. Curr. Oncol. 2025, 32, 383. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol32070383

Rimbu MC, Ungureanu FD, Moldovan C, Toba ME, Chirila M, Truta E, Cord D. Atypical Cystic Primary Hepatic GIST: A Case Report of Rare Presentation and Long-Term Survival. Current Oncology. 2025; 32(7):383. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol32070383

Chicago/Turabian StyleRimbu, Mirela Claudia, Florin Dan Ungureanu, Cosmin Moldovan, Madalina Elena Toba, Marinela Chirila, Elena Truta, and Daniel Cord. 2025. "Atypical Cystic Primary Hepatic GIST: A Case Report of Rare Presentation and Long-Term Survival" Current Oncology 32, no. 7: 383. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol32070383

APA StyleRimbu, M. C., Ungureanu, F. D., Moldovan, C., Toba, M. E., Chirila, M., Truta, E., & Cord, D. (2025). Atypical Cystic Primary Hepatic GIST: A Case Report of Rare Presentation and Long-Term Survival. Current Oncology, 32(7), 383. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol32070383