Implementation of Organ Preservation for Locally Advanced Rectal Cancer in Canada: A National Survey of Clinical Practice

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Study Design and Setting

2.2. Sample Characteristics

2.3. Data Collection Methods

2.4. Survey Administration

2.5. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Respondent Characteristics

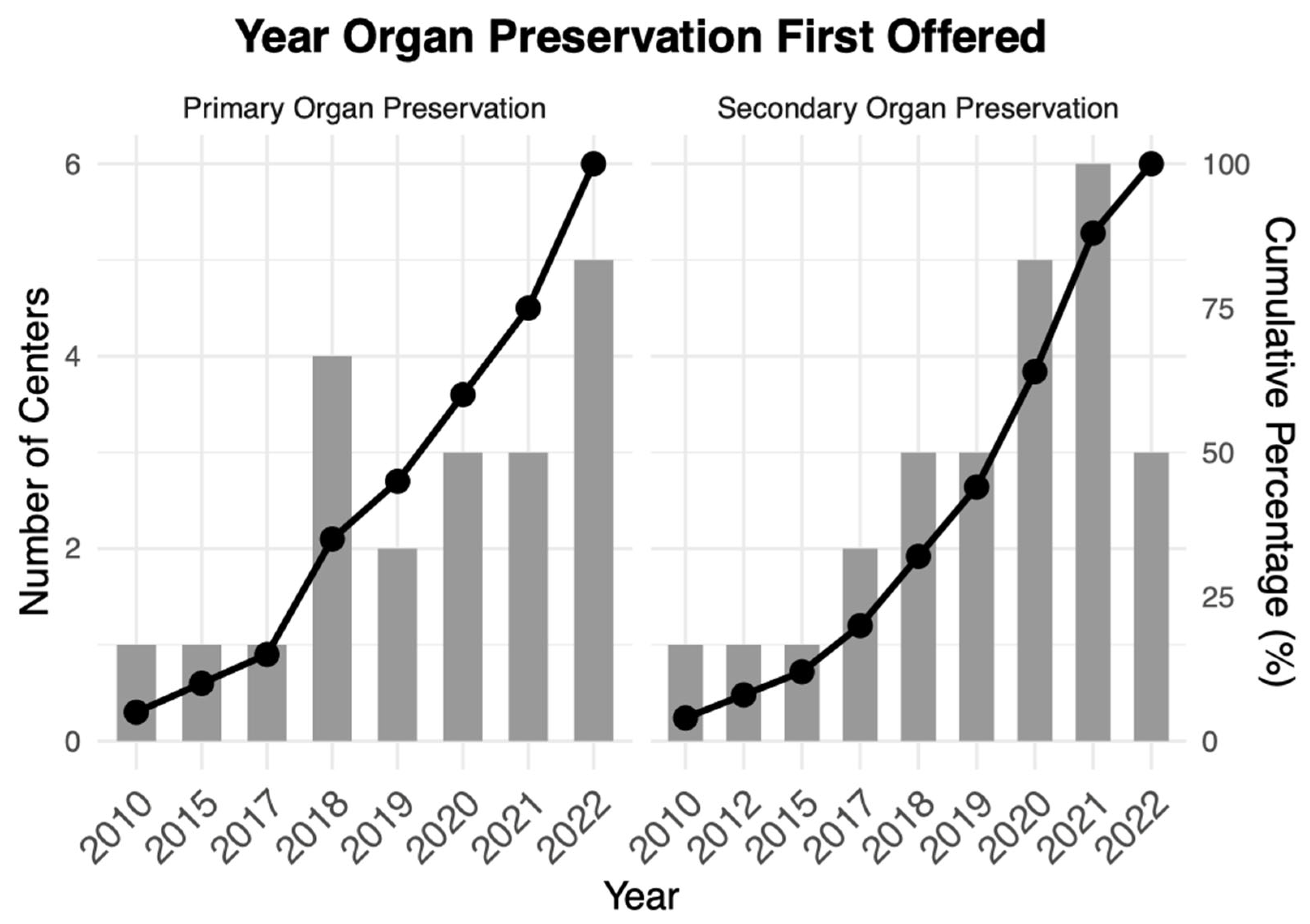

3.2. Implementation of Organ Preservation

3.3. Variability in Patient Selection for Organ Preservation

3.4. Variability in Neoadjuvant Treatment Strategies in Organ Preservation

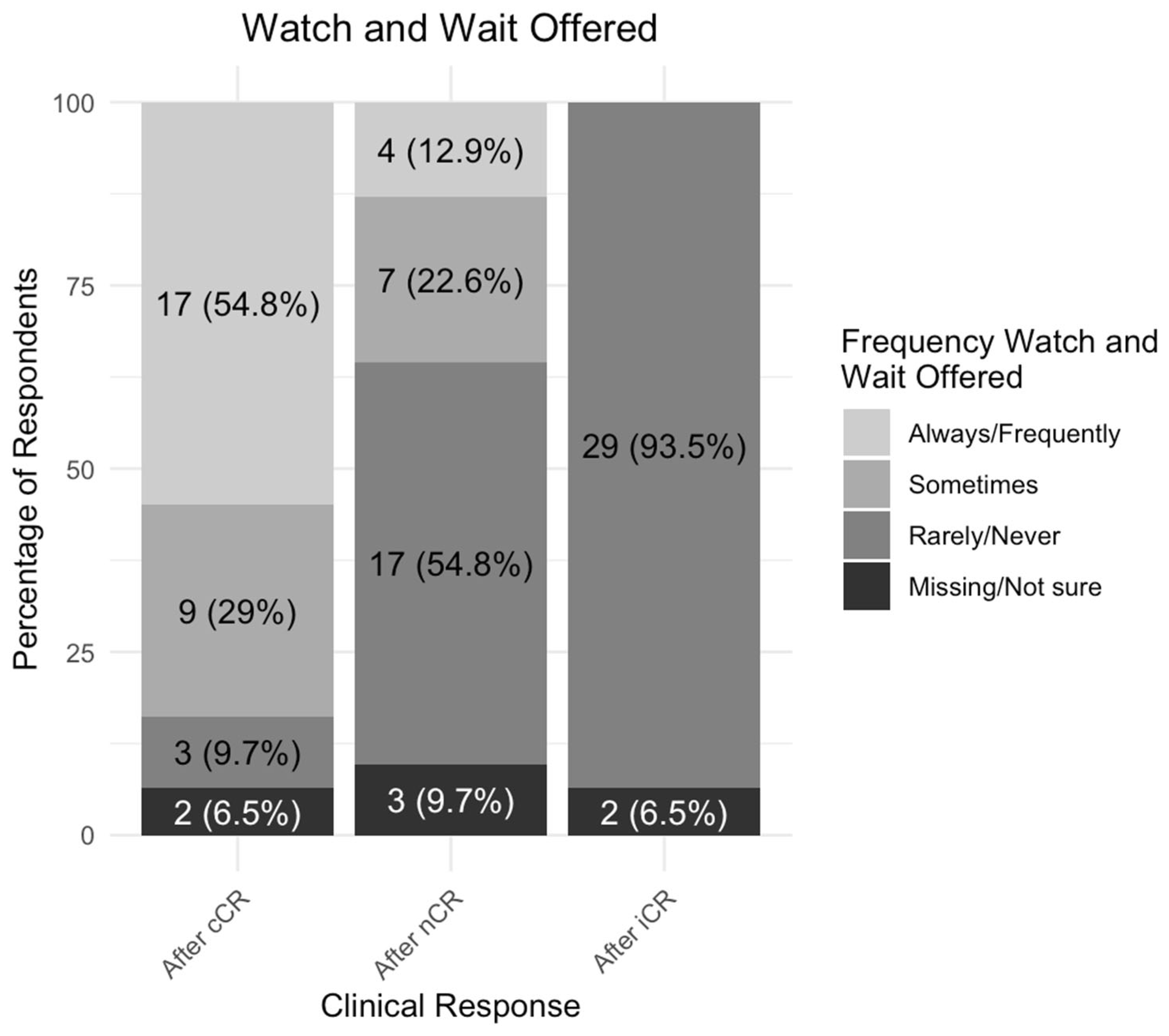

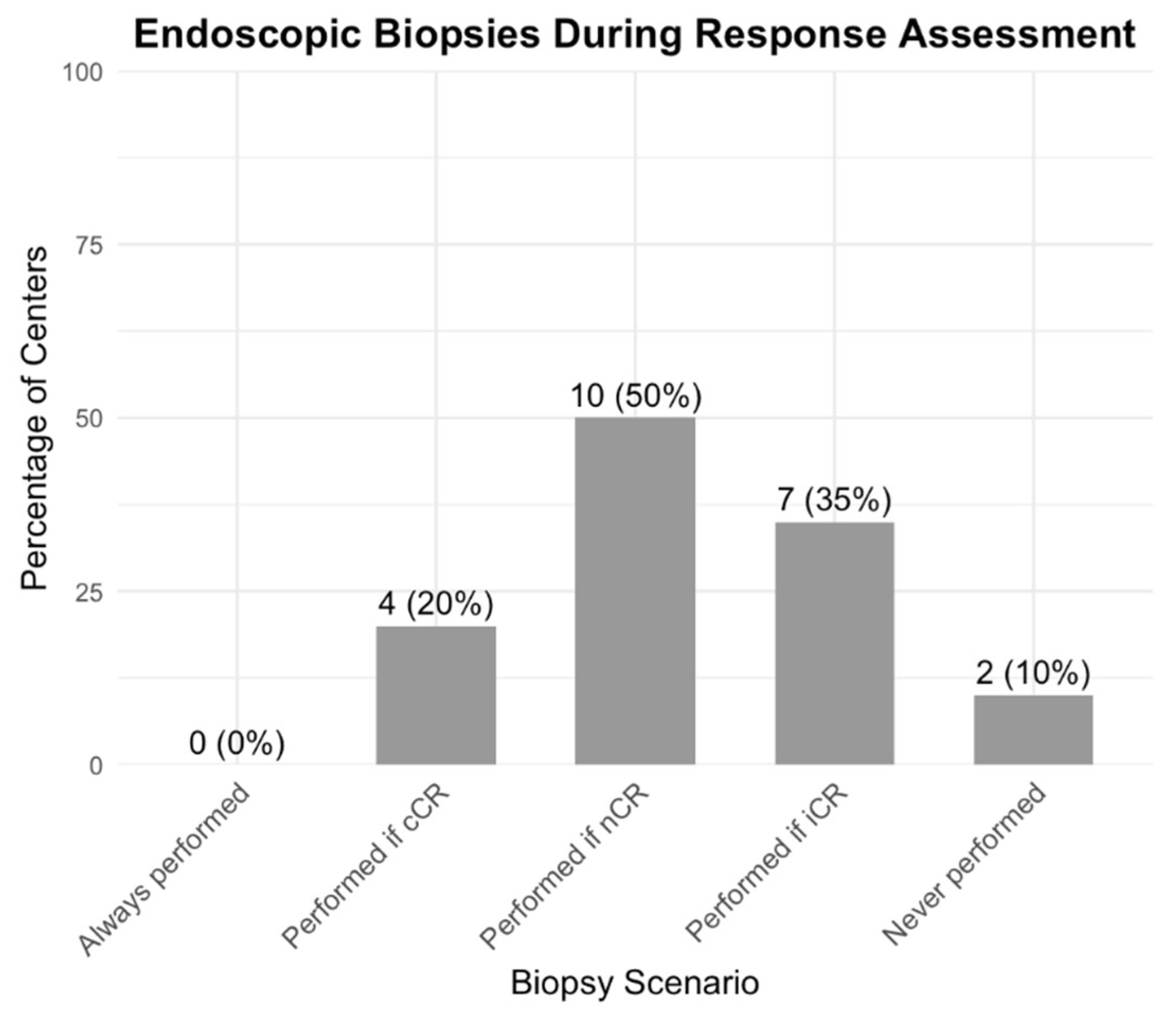

3.5. Variability in the Assessment of Tumor Response and Watch-and-Wait Surveillance

3.6. Variability in Resources for Quality Assurance for Organ Preservation

3.7. Challenges and Areas for Improvement

4. Discussion

5. Limitations

6. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Key Term | Definition |

|---|---|

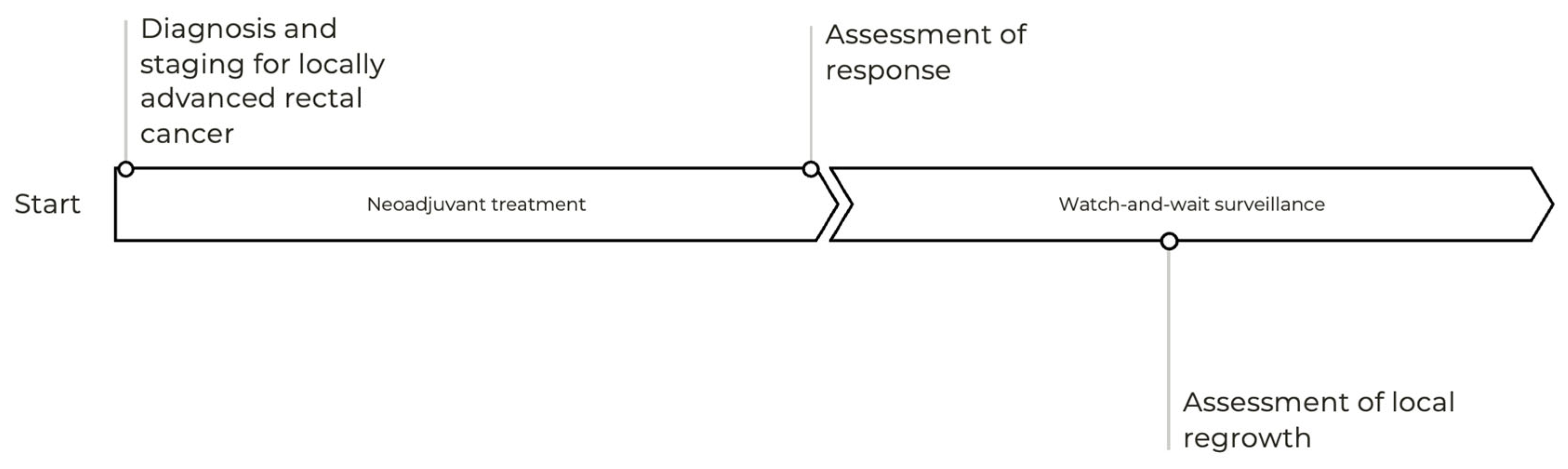

| Assessment of response | The use of clinical, radiological and/or pathological investigations after completion of therapy in primary organ preservation to determine their eligibility for watch-and-wait surveillance vs. surgical management |

| Clinical complete response | No residual disease, as determined through clinical, endoscopic, and radiological assessments |

| Clinical incomplete response | Minimal or no response to treatment, with clear evidence of residual tumor in the bowel wall or mesorectal nodes. |

| Clinical near-complete response | Substantial treatment response that does not fully meet the criteria for a clinical complete response. |

| Locally advanced rectal cancer | Stage II/III, T1-2N+ or T3/4N any |

| Primary organ preservation | A treatment strategy where neoadjuvant therapy is administered with the explicit goal of achieving a clinical complete or near-complete response, thereby avoiding total mesorectal excision |

| Secondary organ preservation | A treatment strategy where neoadjuvant therapy is administered and a complete clinical response or near-complete clinical response is achieved, thereby avoiding total mesorectal excision, despite the primary aim of neoadjuvant treatment being to proceed with surgery |

| Watch and wait surveillance | A strict surveillance protocol following a clinical complete or near-complete response, applicable to both primary and secondary organ preservation |

References

- Kasi, A.; Abbasi, S.; Handa, S.; Al-Rajabi, R.; Saeed, A.; Baranda, J.; Sun, W. Total Neoadjuvant Therapy vs Standard Therapy in Locally Advanced Rectal Cancer. JAMA Netw. Open 2020, 3, e2030097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cho, J.R.; Jeong, S.-Y.; Oh, J.H.; Ahn, S.; Choi, S.; Kim, D.-W.; Lee, B.H.; Youk, E.G.; Park, S.C.; Heo, S.C.; et al. Quality of life after sphincter preservation surgery or abdominoperineal resection for low rectal cancer (ASPIRE): A long-term prospective, multicentre, cohort study. Lancet Reg. Heal.—West. Pac. 2021, 6, 100087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maas, M.; Nelemans, P.J.; Valentini, V.; Das, P.; Rödel, C.; Kuo, L.-J.; A Calvo, F.; García-Aguilar, J.; Glynne-Jones, R.; Haustermans, K.; et al. Long-term outcome in patients with a pathological complete response after chemoradiation for rectal cancer: A pooled analysis of individual patient data. Lancet Oncol. 2010, 11, 835–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- You, Y.N.; Hardiman, K.M.; Bafford, A.; Poylin, V.; Francone, T.D.; Davis, K.; Paquette, I.M.; Steele, S.R.; Feingold, D.L. The American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons Clinical Practice Guidelines for the Management of Rectal Cancer. Dis. Colon Rectum 2020, 63, 1191–1222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fokas, E.; Appelt, A.; Glynne-Jones, R.; Beets, G.; Perez, R.; Garcia-Aguilar, J.; Rullier, E.; Smith, J.J.; Marijnen, C.; Peters, F.P.; et al. International consensus recommendations on key outcome measures for organ preservation after (chemo)radiotherapy in patients with rectal cancer. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2021, 18, 805–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofheinz, R.-D.; Fokas, E.; Benhaim, L.; Price, T.J.; Arnold, D.; Beets-Tan, R.; Guren, M.G.; Hospers, G.A.P.; Lonardi, S.; Nagtegaal, I.D.; et al. Localised rectal cancer: ESMO Clinical Practice Guideline for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann. Oncol. 2025, in press. [CrossRef]

- Langenfeld, S.J.; Davis, B.R.; Vogel, J.D.; Davids, J.S.; Temple, L.K.; Cologne, K.G.; Hendren, S.; Hunt, S.; Aguilar, J.G.; Feingold, D.L.; et al. The American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons Clinical Practice Guidelines for the Management of Rectal Cancer 2023 Supplement. Dis. Colon Rectum 2023, 67, 18–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, A.J.; Kennedy, E.B.; Berlin, J.; Brown, G.; Chalabi, M.; Cho, M.T.; Cusnir, M.; Dorth, J.; George, M.; Kachnic, L.A.; et al. Management of Locally Advanced Rectal Cancer: ASCO Guideline. J. Clin. Oncol. 2024, 42, 3355–3375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Comprehensive Cancer Network NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology (NCCN Guidelines®) Rectal Cancer. 2025. Available online: https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/rectal.pdf (accessed on 30 May 2025).

- López-Campos, F.; Martín-Martín, M.; Fornell-Pérez, R.; García-Pérez, J.C.; Die-Trill, J.; Fuentes-Mateos, R.; López-Durán, S.; Domínguez-Rullán, J.; Ferreiro, R.; Riquelme-Oliveira, A.; et al. Watch and wait approach in rectal cancer: Current controversies and future directions. World J. Gastroenterol. 2020, 26, 4218–4239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A.; Duc, N.T.M.; Thang, T.L.L.; Nam, N.H.; Ng, S.J.; Abbas, K.S.; Huy, N.T.; Marušić, A.; Paul, C.L.; Kwok, J.; et al. A Consensus-Based Checklist for Reporting of Survey Studies (CROSS). J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2021, 36, 3179–3187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pahwa, M.; Cavanagh, A.; Vanstone, M. Key Informants in Applied Qualitative Health Research. Qual. Heal. Res. 2023, 33, 1251–1261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caycedo-Marulanda, A.; Patel, S.V.; Verschoor, C.P.; Uscategui, J.P.; Chadi, S.A.; Moeslein, G.; Chand, M.; Maeda, Y.; Monson, J.R.T.; Wexner, S.D.; et al. A Snapshot of the International Views of the Treatment of Rectal Cancer Patients, a Multi-regional Survey: International Tendencies in Rectal Cancer. World J. Surg. 2020, 45, 302–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keyworth, C.; Epton, T.; Goldthorpe, J.; Calam, R.; Armitage, C.J. Acceptability, reliability, and validity of a brief measure of capabilities, opportunities, and motivations (“COM-B”). Br. J. Heal. Psychol. 2020, 25, 474–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maxwell, J.; Roberts, A.; Cil, T.; Somogyi, R.; Osman, F. Current Practices and Barriers to the Integration of Oncoplastic Breast Surgery: A Canadian Perspective. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2016, 23, 3259–3265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panje, C.M.; Glatzer, M.; Von Rappard, J.; Rothermundt, C.; Hundsberger, T.; Zumstein, V.; Plasswilm, L.; Putora, P.M. Applied Swarm-based medicine: Collecting decision trees for patterns of algorithms analysis. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2017, 17, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reames, B.N.; Blair, A.B.; Krell, R.W.; Groot, V.P.; Gemenetzis, G.; Padussis, J.C.; Thayer, S.P.; Falconi, M.; Wolfgang, C.L.; Weiss, M.J.; et al. Management of Locally Advanced Pancreatic Cancer. Ann. Surg. 2019, 273, 1173–1181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steffen, T.; Eden, J.; Bijelic, L.; Glatzer, M.; Glehen, O.; Goéré, D.; de Hingh, I.; Li, Y.; Moran, B.; Morris, D.; et al. Patient Selection for Hyperthermic Intraperitoneal Chemotherapy in Patients With Colorectal Cancer: Consensus on Decision Making Among International Experts. Clin. Color. Cancer 2020, 19, 277–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, T.C.; Sanford, N.N.; Anand, S.; Chu, F.-I.; Wo, J.Y.; Raldow, A.C. Current Practice Patterns in Locally Advanced Rectal Cancer at Academic Institutions: A National Survey Among Radiation Oncologists, Medical Oncologists, and Colorectal Surgeons. Clin. Color. Cancer 2022, 21, 309–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yahya, J.; Herzig, D.; Farrell, M.; Degnin, C.; Chen, Y.; Holland, J.; Brown, S.; Binder, C.; Jaboin, J.; Tsikitis, V.L.; et al. Survey results of US radiation oncology providers’ contextual engagement of watch-and-wait beliefs after a complete clinical response to chemoradiation in patients with local rectal cancer. J. Gastrointest. Oncol. 2018, 9, 1127–1132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glasgow, R.E.; Vogt, T.M.; Boles, S.M. Evaluating the public health impact of health promotion interventions: The RE-AIM framework. Am. J. Public Health 1999, 89, 1322–1327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffmann, T.C.; Glasziou, P.P.; Boutron, I.; Milne, R.; Perera, R.; Moher, D.; Altman, D.G.; Barbour, V.; Macdonald, H.; Johnston, M.; et al. Better reporting of interventions: Template for intervention description and replication (TIDieR) checklist and guide. BMJ 2014, 348, g1687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burns, K.E.; Duffett, M.; Kho, M.E.; Meade, M.O.; Adhikari, N.K.; Sinuff, T.; Cook, D.J. For the ACCADEMY Group A guide for the design and conduct of self-administered surveys of clinicians. Can. Med Assoc. J. 2008, 179, 245–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Habr-Gama, A.; Perez, R.O.; Nadalin, W.; Sabbaga, J.; Ribeiro, U., Jr.; Silva e Sousa, A.H., Jr.; Campos, F.G.; Kiss, D.R.; Gama-Rodrigues, J. Operative Versus Nonoperative Treatment for Stage 0 Distal Rectal Cancer Following Chemoradiation Therapy: Long-term results. Ann. Surg. 2004, 240, 711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gani, C.; Gani, N.; Zschaeck, S.; Eberle, F.; Schaeffeler, N.; Hehr, T.; Berger, B.; Fischer, S.G.; Claßen, J.; Zipfel, S.; et al. Organ Preservation in Rectal Cancer: The Patients’ Perspective. Front. Oncol. 2019, 9, 318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Couwenberg, A.M.; Intven, M.P.M.; Burbach, J.P.M.; Emaus, M.J.M.; van Grevenstein, W.M.M.; Verkooijen, H.M.M. Utility Scores and Preferences for Surgical and Organ-Sparing Approaches for Treatment of Intermediate and High-Risk Rectal Cancer. Dis. Colon Rectum 2018, 61, 911–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smits, L.J.H.; van Lieshout, A.S.; Debets, S.; Spoor, S.; Moons, L.M.G.; Peeters, K.C.M.J.; van Oostendorp, S.E.; Damman, O.C.; Janssens, R.J.P.A.; Lameris, W.; et al. Patients’ perspectives and the perceptions of healthcare providers in the treatment of early rectal cancer; a qualitative study. BMC Cancer 2023, 23, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jessop, J.; Beagley, C.; Heald, R.J. The Pelican Cancer Foundation and The English National MDT-TME Development Programme. Color. Dis. 2006, 8, 1–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moran, B.J.; Holm, T.; Brannagan, G.; Chave, H.; Quirke, P.; West, N.; Brown, G.; Glynne-Jones, R.; Sebag-Montefiore, D.; Cunningham, C.; et al. The English National Low Rectal Cancer Development Programme: Key messages and future perspectives. Color. Dis. 2013, 16, 173–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dayal, S.; Moran, B.; Thompson, C.; Williams, J.G.; Myint, A.S.; Carter, P.; Hershman, M.J.; Maslekar, S.; Anwar, S. LOREC: The English Low Rectal Cancer National Development Programme. Br. J. Hosp. Med. 2013, 74, 377–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maas, M.; Lambregts, D.M.J.; Nelemans, P.J.; Heijnen, L.A.; Martens, M.H.; Leijtens, J.W.A.; Sosef, M.; Hulsewé, K.W.E.; Hoff, C.; Breukink, S.O.; et al. Assessment of Clinical Complete Response After Chemoradiation for Rectal Cancer with Digital Rectal Examination, Endoscopy, and MRI: Selection for Organ-Saving Treatment. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2015, 22, 3873–3880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Duan, B.; Liu, R.; Zhu, M.; Zhao, G.; Guan, N.; Wang, Y. Enhancing Clinical Complete Response Assessment in Rectal Cancer: Integrating Transanal Multipoint Full-Layer Puncture Biopsy Criteria: A Systematic Review. Front Oncol. 2024, 14, 1428583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ko, H.M.; Choi, Y.H.; Lee, J.E.; Lee, K.H.; Kim, J.Y.; Kim, J.S. Combination Assessment of Clinical Complete Response of Patients With Rectal Cancer Following Chemoradiotherapy With Endoscopy and Magnetic Resonance Imaging. Ann. Coloproctology 2019, 35, 202–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kokaine, L.; Gardovskis, A.; Gardovskis, J. Evaluation and Predictive Factors of Complete Response in Rectal Cancer after Neoadjuvant Chemoradiation Therapy. Medicina 2021, 57, 1044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Felder, S.I.; Patil, S.; Kennedy, E.; Garcia-Aguilar, J. Endoscopic Feature and Response Reproducibility in Tumor Assessment after Neoadjuvant Therapy for Rectal Adenocarcinoma. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2021, 28, 5205–5223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verheij, F.S.; Omer, D.M.; Williams, H.; Lin, S.T.; Qin, L.-X.; Buckley, J.T.; Thompson, H.M.; Yuval, J.B.; Kim, J.K.; Dunne, R.F.; et al. Long-Term Results of Organ Preservation in Patients with Rectal Adenocarcinoma Treated with Total Neoadjuvant Therapy: The Randomized Phase II OPRA Trial. J. Clin. Oncol. 2024, 42, 500–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baron, D.; Loscos, T.P.; Schiappa, R.; Barbet, N.; Dost, E.; Ben Dhia, S.; Soltani, S.; Mineur, L.; Martel, I.; Horn, S.; et al. A phase III randomised trial on the addition of a contact X-ray brachytherapy boost to standard neoadjuvant chemo-radiotherapy for organ preservation in early rectal adenocarcinoma: 5 year results of the OPERA trial. Ann. Oncol. 2024, 36, 208–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ESTRO 2025—Abstract Book. Available online: https://user-swndwmf.cld.bz/ESTRO-2025-Abstract-Book/12/ (accessed on 31 May 2025).

- Garant, A.; Vasilevsky, C.-A.; Boutros, M.; Khosrow-Khavar, F.; Kavan, P.; Diec, H.; Groseilliers, S.D.; Faria, J.; Ferland, E.; Pelsser, V.; et al. MORPHEUS Phase II–III Study: A Pre-Planned Interim Safety Analysis and Preliminary Results. Cancers 2022, 14, 3665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bach, S.P. The STAR-TREC Collaborative Can we Save the rectum by watchful waiting or TransAnal surgery following (chemo)Radiotherapy versus Total mesorectal excision for early REctal Cancer (STAR-TREC)? Protocol for the international, multicentre, rolling phase II/III partially randomized patient preference trial evaluating long-course concurrent chemoradiotherapy versus short-course radiotherapy organ preservation approaches. Color. Dis. 2022, 24, 639–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wurschi, G.W.; Rühle, A.; Domschikowski, J.; Trommer, M.; Ferdinandus, S.; Becker, J.-N.; Boeke, S.; Sonnhoff, M.; Fink, C.A.; Käsmann, L.; et al. Patient-Relevant Costs for Organ Preservation versus Radical Resection in Locally Advanced Rectal Cancer. Cancers 2024, 16, 1281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bunjo, Z.; Bunjo, Z.; Seow, W.; Seow, W.; Murshed, I.; Murshed, I.; Bedrikovetski, S.; Bedrikovetski, S.; Thomas, M.; Thomas, M.; et al. Economic Evaluation of ‘Watch and Wait’ Following Neoadjuvant Therapy in Locally Advanced Rectal Cancer: A Systematic Review. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2024, 32, 137–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bibi, S.; Edilbe, M.; Rao, C. The Cost-effectiveness of Watch and Wait for Rectal Cancer. Clin. Oncol. 2022, 35, 132–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loria, A.; Ramsdale, E.E.; Aquina, C.T.; Cupertino, P.; Mohile, S.G.; Fleming, F.J. From Clinical Trials to Practice: Anticipating and Overcoming Challenges in Implementing Watch-and-Wait for Rectal Cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2024, 42, 876–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nasim, B.W.; Murphy, S.; Yracheta, J.; Clark, A.L.; Veluri, S.L.; Katabathina, V.; Parikh, A.; Campi, H.D.; Feferman, Y.; Russell, T.A.; et al. Barriers to Offering Organ Preservation for Rectal Cancer in a Predominantly Hispanic Safety Net Hospital. J. Surg. Oncol. 2024, 131, 183–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gani, C.; Bonomo, P.; Zwirner, K.; Schroeder, C.; Menegakis, A.; Rödel, C.; Zips, D. Organ preservation in rectal cancer—Challenges and future strategies. Clin. Transl. Radiat. Oncol. 2017, 3, 9–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palinkas, L.A.; Horwitz, S.M.; Green, C.A.; Wisdom, J.P.; Duan, N.; Hoagwood, K. Purposeful Sampling for Qualitative Data Collection and Analysis in Mixed Method Implementation Research. Adm. Policy Ment. Health Ment. Health Serv. Res. 2015, 42, 533–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristics | n (%) or Median (IQR) |

|---|---|

| Geographical Region | |

| Atlantic (NFL, PEI, NS, NB) | 4 (10.0%) |

| Quebec | 10 (25.0%) |

| Ontario | 15 (37.5%) |

| Prairies (MB, SK, AB) | 5 (12.5%) |

| British Columbia | 6 (15.0%) |

| Type of Radiation Center | |

| Non-university-affiliated community center | 3 (7.5%) |

| University-affiliated community center | 16 (40.0%) |

| University-affiliated tertiary/quaternary center | 21 (52.5%) |

| Specialty | |

| Medical oncology | 3 (7.5%) |

| Radiation oncology | 24 (60.0%) |

| Surgery | 13 (32.5%) |

| Clinical Experience | |

| Years in practice | 8 (5–15) |

| Year started practice at current institution | 2015 (2008–2018) |

| Number of rectal cancer consults per month | 4 (3–6) |

| Resources for Managing Locally Advanced Rectal Cancer | |

| MRI | 40 (100.0%) |

| CT | 40 (100.0%) |

| Endoscopy | 39 (97.5%) |

| EUS | 8 (20.0%) |

| PET Scan | 6 (15.0%) |

| GI-specialized pathology | 30 (75.0%) |

| GI-specialized medical oncology | 39 (97.5%) |

| GI-specialized radiation oncology | 39 (97.5%) |

| Rectal cancer clinical trials | 19 (47.5%) |

| AYA program | 1 (2.5%) |

| Psychosocial oncology program | 17 (42.5%) |

| Laparoscopy | 32 (80.0%) |

| Robotic | 2 (5.0%) |

| MCC Frequency | |

| Every two weeks | 14 (35.0%) |

| Weekly | 26 (65.0%) |

| Patients with Locally Advanced Rectal Cancer Discussed at MCC Before Neoadjuvant Treatment | |

| 0–20% | 2 (5.0%) |

| 21–40% | 5 (12.5%) |

| 41–60% | 2 (5.0%) |

| 61–80% | 8 (20.0%) |

| 81–100% | 23 (57.5%) |

| Patients with Locally Advanced Rectal Cancer Discussed at MCC After Neoadjuvant Treatment and Before Surgery | |

| 0–20% | 20 (50.0%) |

| 21–40% | 2 (5.0%) |

| 41–60% | 6 (15.0%) |

| 61–80% | 6 (15.0%) |

| 81–100% | 4 (10.0%) |

| Missing | 2 (5.0%) |

| Status of Organ Preservation | |

| Primary and secondary organ preservation are offered | 20 (50.0%) |

| Secondary organ preservation is offered only | 11 (27.8%) |

| Organ preservation is not offered | 8 (20.0%) |

| Missing | 1 (2.5%) |

| Year Organ Preservation First Offered | |

| Primary and secondary organ preservation | 2020 (2018–2022) |

| Secondary organ preservation | 2020 (2018–2021) |

| Category | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Before Neoadjuvant Treatment | |

| 0–20% | 1 (5.0%) |

| 21–40% | 2 (10.0%) |

| 41–60% | 2 (10.0%) |

| 61–80% | 3 (15.0%) |

| 81–100% | 12 (60.0%) |

| After Assessment of Response | |

| 0–20% | 5 (25.0%) |

| 21–40% | 1 (5.0%) |

| 41–60% | 3 (15.0%) |

| 61–80% | 1 (5.0%) |

| 81–100% | 10 (50.0%) |

| Perceived Challenges (Select All That Apply) | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Access to MRI | 21 (52.5%) |

| Clinic time/space for the number of required assessments | 18 (45.0%) |

| Access to timely surgery if required | 16 (40.0%) |

| Lack of comfort/familiarity with long-term outcomes of supporting evidence | 15 (37.5%) |

| Staff capacity for the number of required assessments | 14 (35.0%) |

| Access to endoscopy | 13 (32.5%) |

| Lack of comfort/familiarity with the strength of supporting evidence | 13 (32.5%) |

| Access to the cancer center | 12 (30.0%) |

| Lack of comfort/familiarity with the clinical and radiological assessment and surveillance protocols | 11 (27.5%) |

| Suboptimal coordination among multidisciplinary team | 10 (25.0%) |

| Lack of comfort/familiarity with the necessary treatment protocols | 7 (17.5%) |

| Missing | 2 (5.0%) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Delisle, M.; Ivankovic, V.; Goubran, D.; Paglicauan, E.Y.; Alsobaei, M.; Alcasid, N.; Farnand, M.; Dennis, K. Implementation of Organ Preservation for Locally Advanced Rectal Cancer in Canada: A National Survey of Clinical Practice. Curr. Oncol. 2025, 32, 341. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol32060341

Delisle M, Ivankovic V, Goubran D, Paglicauan EY, Alsobaei M, Alcasid N, Farnand M, Dennis K. Implementation of Organ Preservation for Locally Advanced Rectal Cancer in Canada: A National Survey of Clinical Practice. Current Oncology. 2025; 32(6):341. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol32060341

Chicago/Turabian StyleDelisle, Megan, Victoria Ivankovic, Doris Goubran, Eliane Yvonne Paglicauan, Mariam Alsobaei, Nicole Alcasid, Mary Farnand, and Kristopher Dennis. 2025. "Implementation of Organ Preservation for Locally Advanced Rectal Cancer in Canada: A National Survey of Clinical Practice" Current Oncology 32, no. 6: 341. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol32060341

APA StyleDelisle, M., Ivankovic, V., Goubran, D., Paglicauan, E. Y., Alsobaei, M., Alcasid, N., Farnand, M., & Dennis, K. (2025). Implementation of Organ Preservation for Locally Advanced Rectal Cancer in Canada: A National Survey of Clinical Practice. Current Oncology, 32(6), 341. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol32060341