Abstract

Due to new treatment options, the number of patients living longer with advanced cancer is rapidly growing. While this is promising, many long-term responders (LTRs) face difficulties adapting to life with cancer due to persistent uncertainty, feeling misunderstood, and insufficient tools to navigate their “new normal”. Using the Person-Based Approach, this study developed and evaluated a website in co-creation with LTRs, healthcare professionals, and service providers, offering evidence-based information and tools for LTRs. We identified the key issues (i.e., living with uncertainty, relationships with close others, mourning losses, and adapting to life with cancer) and established the website’s main goals: acknowledging and normalizing emotions, difficulties, and challenges LTRs face and providing tailored information and practical tools. The prototype was improved through repeated feedback from a user panel (n = 9). In the evaluation phase (n = 43), 68% of participants rated the website’s usability as good or excellent. Interview data indicated that participants experienced recognition through portrait videos and quotes, valued the psycho-education via written text and (animated) videos, and made use of the practical tools (e.g. conversation aid), confirming that the main goals were achieved. Approximately 90% of participants indicated they would recommend the website to other LTRs. The Dutch website—Doorlevenmetkanker (i.e., continuing life with cancer) was officially launched in March 2025 in the Netherlands.

1. Introduction

Long-term responders (LTRs) are patients with advanced (i.e., unresectable metastatic) cancer who obtain durable survival rates due to effective treatment with new medical therapies such as immunotherapy or targeted therapy [1,2]. While it is good news that treatment is effective in prolonging life, living long-term with an uncertain prognosis comes with challenges. Approximately half of these patients report heightened levels of distress or fear of worsening of their disease [3,4]. LTRs often feel misunderstood by their social environment because most people live under the impression that individuals either recover or die from cancer rather than living with advanced cancer for an extended period [1]. Due to their uncertain life perspective, LTRs go back and forth between feeling like a patient or feeling healthy. The persistent uncertainty about the potential recurrence or progression of cancer makes it difficult for LTRs to make future plans. Consequently, many LTRs struggle to adapt to life with advanced cancer [1] and report multiple unmet needs [2,5,6].

To help them adapt, there is a need for support that is specifically tailored to LTRs because they find no recognition in the existing information for curative or palliative-treated patients [1]. As a result, one of the most pressing unmet needs reported by LTRs is the need for more tailored information [2,5,6]. We would like to offer LTRs easily accessible and evidence-based information and practical tools to acknowledge that living with cancer comes with many challenges and to help them manage the continuing stressors and uncertainty they are facing. Providing readily accessible support via a website can potentially prevent psychological problems and reduce the need for psychological care. As the LTR group is expected to grow in the coming years [7], placing additional strain on the healthcare system, a website designed for LTRs to use independently–requiring no support from healthcare providers–could help alleviate this burden.

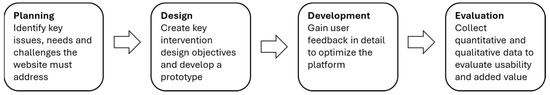

There is widespread consensus in the eHealth research community that eliciting and addressing the needs and perspectives of the intended user is a vital part of good intervention development to ensure (at a minimum) that the website is usable and engaging. This has been confirmed by previous studies in which web-based interventions were developed in co-creation with (advanced) cancer patients and healthcare professionals, showing that the co-creation process provided unique insight into the requirements of the intervention, offering a strong foundation to aid further development (e.g., [8,9,10]). In turn, patients positively evaluate these co-created interventions, indicating good usability, strong functionality, and added value. Since fully anticipating user priorities and needs is challenging, the Person-Based Approach by Yardley and colleagues provides a structured way to improve user experience and strengthen theory- and evidence-based intervention developments (see Figure 1) [11]. It involves qualitative research with LTRs and psychologists carried out at every stage of intervention development. Insights from this process are used to anticipate and interpret website usage and outcomes and, most importantly, to modify the website to make it more feasible and relevant to LTRs. The aim of this study is to develop a psychosocial support website for long-term responders in co-creation with patients, psychologists, and service providers and evaluate the feasibility and usability of this website using the Person-Based Approach [11].

Figure 1.

Person-Based Approach.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design

Within the IMPRESS project, we developed and evaluated a psychological support website for LTRs using the Person-Based Approach [8], which consisted of (1) planning, (2) design, (3) development, and (4) evaluation phases. In the planning phase, we identified the key issues, needs, and challenges the website must address. In the design phase, we established the main goals of the website and developed a prototype. In the development phase, feedback from a user panel was gained to make changes to the website. In the evaluation phase, we assessed the usability and added value of the website among LTRs using a pre-post design (see Figure 1).

2.2. Participants

For the development phase and evaluation phase, participants were recruited at one mental healthcare institute for those affected by cancer (Helen Dowling Institute), two academic medical centers (UMC Utrecht, Radboudumc), and through the social media channels of patient associations. Participants were considered eligible when diagnosed with advanced cancer with a confirmed response or long-term stable disease while on immunotherapy or targeted therapy. At least a third control scan after starting immunotherapy or targeted therapy should have confirmed the response to treatment. Participants needed to be adults, able to sufficiently use and understand the Dutch language and have internet access.

2.3. Procedures

2.3.1. Planning

First, we examined the knowledge we gained from our earlier qualitative research and ecological momentary assessment studies in LTRs [1,12]. In our qualitative studies, we found that LTRs faced challenges in redefining their identity. They often felt caught between not identifying as patients yet not feeling entirely healthy, contributing to them going back and forth between hope and despair due to ongoing uncertainties. They were frequently confronted with an uncertain life perspective during medical check-ups. Upon realizing that returning to their pre-diagnosis life was impossible, they had to adjust to a new normal [1]. In response, LTRs are proactively seeking ways to regain control, shift their perspective, and realign their lives with value [12]. Exploratory findings from our Ecological Momentary Assessment study into the resilience shown in the daily lives of LTRs suggested that optimism, illness acceptance, mindfulness, and positive emotions, in general, are supportive factors to help LTRs manage stressors in daily life [13].

To elicit LTRs’ views on what key issues the website needs to address, we participated in the volunteer day of the patient association Longkanker Nederland. A brainstorming session with volunteers (including LTRs and their close others) highlighted peer support, communication between LTRs and their close others, and work-related issues as key topics. Despite their best efforts, close others often struggled to find the best ways to support LTRs and take care of themselves. Additionally, the accessibility of the website emerged as a crucial topic, emphasizing the need to provide LTRs with information through various formats (e.g., text, video, or animation). Lastly, we also consulted psychologists who have specific experience with treating metastatic cancer patients responding to immunotherapy or targeted therapy and other (international) researchers in the field of psycho-oncology to help us identify the issues and needs the website should address.

We presented all input to the scientific advisory board of the IMPRESS project, which comprised a patient (n = 1), patient representatives (n = 2), an oncologist (n = 1), researchers (n = 2), and researchers who also worked as psychologist (n = 3) in the field of psycho-oncology. The main topics that emerged during the group discussion included living with uncertainty, closeness to others, mourning one’s losses, acknowledging death and dying, and adapting to life with cancer.

2.3.2. Website Design

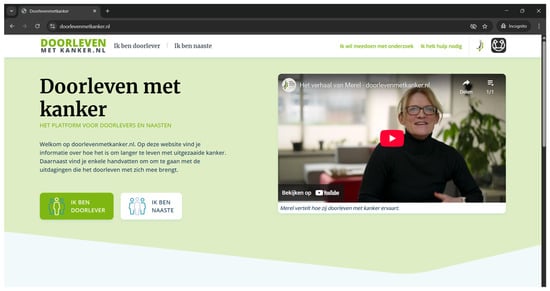

Together with the scientific advisory board, we created the main goals of the website: (1) acknowledging difficulties and challenges that LTRs have to live with; (2) normalizing feelings induced by these difficulties and challenges; and (3) providing LTRs with tailored information and practical tools. We identified the primary objectives for the intervention design, which are based on the key issues highlighted in phase 1: living with uncertainty, relationships with close others, mourning losses, and adapting to life with cancer. Next, we outlined the essential features of the website required to meet these objectives. Specifically, we discussed and decided upon which themes should be covered on the website and the formats through which they should be presented (see Table 1). Together with a software provider, we created the design and structure of the website. With feedback from LTRs, the patient association Longkanker Nederland, and healthcare professionals, we created psycho-education texts. In collaboration with service providers and with feedback from healthcare professionals, we created therapist videos, LTR interview videos, and animation videos. We selected quotes describing how LTRs experience obtaining a long-term response from our previous interview studies [1,9]. Together with healthcare professionals, we developed exercises for the website. Lastly, we added links to other relevant websites. Eventually, this resulted in the prototype of the website (see Figure 2).

Table 1.

Overview of website features.

Figure 2.

Homepage of the website.

2.3.3. Development

To test the prototype of the website, a user panel was assembled. The therapist, physician, or nurse practitioner identified eligible patients and provided them with relevant information. When patients were interested, the physician or research nurse informed the researcher, who then contacted them to explain the study procedure in more detail. After providing informed consent, participants completed a digital questionnaire via SurveyMonkey to provide sociodemographic and clinical characteristics. During the initial use of the prototype, an online think-aloud interview was conducted to gather concrete feedback for website improvement. Participants shared their screens, the online meetings were recorded, and notes were taken by the interviewer. Participants were instructed to verbalize their thoughts regarding the website’s appearance, usability, and content. No specific guidance was provided on which elements to examine, allowing participants to navigate and evaluate the website by themselves. A comprehensive list of feedback was compiled, leading to website adjustments. After two weeks of prototype use, feedback interviews on participants’ overall impressions of the website and their experiences with its content were conducted via telephone or online using Microsoft Teams. Key areas of discussion included appealing aspects of the website, suggestions for improvement, the perceived usefulness of the information provided and tools, and whether participants were utilizing these resources. The feedback from these interviews was used to further refine the prototype, and participants were consulted again until no significant improvements were needed. Additionally, a therapist and a nurse practitioner reviewed the prototype and provided feedback during an interview, which led to several improvements.

2.3.4. Evaluation

For the evaluation of the website, the same recruitment procedures and criteria as those used during the development phase were applied. However, patients were not allowed to participate in both the development and evaluation phases. Upon providing written or digital informed consent, participants completed a set of baseline questionnaires via SurveyMonkey. They were then asked to use the website for one month. Six weeks after completing the baseline questionnaires, participants filled out follow-up questionnaires. In addition, a subsample of participants was interviewed about their experiences with the website.

2.4. Measures

One week before accessing the website (baseline) and six weeks after (follow-up), participants completed the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) and the Brief Resilience Scale (BRS). We used these scales to describe the study population and to see if these variables were stable over time. We did not expect changes from baseline to follow-up.

Psychological distress was measured using the HADS [14]. It consists of 14 items examining anxiety and depression symptoms. An example item from the anxiety subscale is: “I feel tense”, with response options ranging from 0 (“Not at all”) to 3 (“Most of the time”). The HADS shows good psychometric properties in Dutch cancer patients, including reliability, validity, and internal consistency [15].

Resilience was measured with the BRS, which consisted of six items rated on a 5-point Likert scale (from 1 = totally disagree to 5 = totally agree), exploring the extent to which patients generally recovered quickly from adverse events [16]. An example item is the following: “I tend to bounce back quickly after hard times.” The Dutch version of the BRS showed good psychometric properties [17].

Usability (i.e., the ease with which users can effectively and efficiently interact with the website to achieve their goals) was assessed via the System Usability Scale (SUS) [18], which is often used to assess the usability of websites and online interventions, and categorizes them as either poor, okay, good, or excellent. This scale consisted of 10 items, such as “I think that I would like to use this system frequently.” This is rated on a 5-point Likert scale (from 1 = totally disagree to 5 = totally agree). The Dutch version of the SUS is a reliable and valid tool for assessing the usability of healthcare innovations [19].

Three open-ended questions assessed the feasibility of the website. We asked what participants found most appealing, what they missed, and whether and why they would (or would not) recommend the website to other LTRs.

Two research assistants conducted semi-structured interviews to gather additional information about the website’s usability and feasibility (see Table 2 for the topic guide). Both participants who were positive and negative about the website, as indicated by the questionnaires, were invited to the interview to gain the broadest possible insight into the website’s use and usefulness. The research assistants were not involved in the development of the website to avoid potential bias and ensure that the interviewees felt free to comment.

Table 2.

Topic guide for semi-structured interviews.

2.5. Analysis

2.5.1. Power Analysis

We used a pre- and post-intervention design to evaluate the website. Following the recommendation of sample sizes of at least 30 participants in feasibility studies and a median sample size of 43 participants in publicly funded feasibility studies, we aimed to include at least 43 participants in our study [20].

2.5.2. Quantitative Analysis

Paired-sample t-tests were used to examine whether patients’ psychological distress and resilience levels changed from baseline to six weeks after gaining access to the website. Participants with missing data were excluded from the analysis.

Descriptive statistics of the SUS provided an indication of how patients assessed the usage of the website. The website was considered feasible when the majority of participants rated the website as good or excellent.

2.5.3. Qualitative Analysis

Data from the open-ended questions and semi-structured interviews were analyzed with the constant comparative method of the thematic analysis approach [21] using Atlas.ti (version 25) software. Data analysis started as soon as the follow-up questionnaires were completed, and the first interview was transcribed verbatim by the research assistants. Two researchers independently coded the open-ended questions and interviews and constantly compared coding schemes until they reached consensus. After all data were analyzed and consensus was reached, the research team grouped the codes referring to the same topic into subthemes and grouped the subthemes into themes.

3. Results

3.1. Development

3.1.1. User Panel

Between May and July 2024, twelve patients were enrolled in the user panel. Three patients dropped out after receiving instructions due to illness progression (n = 1) and unknown reasons (n = 2). Ultimately, nine participants were included in the analysis, with ages ranging from 40 to 66 years (M = 56.00, SD = 7.42). Five participants were identified as women. All participants had at least an intermediate level of education, with four having attended university. Eight participants were diagnosed with metastatic lung cancer, and one participant was diagnosed with metastatic melanoma. The majority of participants were treated with immunotherapy (n = 6). The time since diagnosis varied from 25 to 88 months (M = 53.00, SD = 19.93). Two participants withdrew after the think-aloud interview due to adversities in their personal life. The data retrieved from the think-aloud interviews of these participants were used in the analysis.

The user panel was completed with a healthcare psychologist and nurse practitioner (author J.v.d.S). In June 2024, they also reviewed the website and provided feedback. The healthcare psychologist worked at the Helen Dowling Institute and had expertise in psychological treatment for cancer patients and, in particular, LTRs for four years. The nurse practitioner worked for 10 years at the Department of Respiratory Diseases, University Medical Centre Utrecht, with extensive experience in treating LTRs.

3.1.2. Feedback on Design and Usability

While some participants felt that the website’s design was somewhat impersonal, for example, because the colors (i.e., different shades of blue and green) reminded them of the clinical environment of hospitals, the majority believed that the calm design was appealing and fitting for the website. Having numerous headings above the text helped participants understand what information they could find on the page.

A key area for improvement regarding design and usability was the excessive click-through options, which caused some participants to lose track of their progress. They reported not always knowing which pages they had already viewed. Consequently, we decreased the number of click-through options and highlighted the current page in the menu bar. Some pages initially appeared too similar, so we ensured the differences were more noticeable, for example, by incorporating different images on each page.

3.1.3. Feedback on Feasibility

In terms of content, the conversation aid was helpful for users as it highlighted the significance of communication with those around them and encouraged deeper contemplation of the themes presented on the website. Presenting experiences from other LTRs through videos and quotes throughout the website significantly distinguished it from other websites, according to the user panel. Participants particularly appreciated the videos and quotes for their strong sense of recognition. The user panel specifically noted that the page on actively taking a role in your own medical care was very helpful as it provided LTRs with a sense of control amidst the uncertainty.

3.1.4. Prototype Modification

Based on the feedback, several content modifications were made to improve the website. First of all, it was recommended to avoid providing information that could vary significantly for each LTR. For example, the text “At first, you may have a check-up scan every month. Later, this may be every 3 months, 6 months, or a year” was suggested to be removed and state that the time between scans may vary during the disease process. Secondly, it was noted that technical terms should be used with caution. For example, the term “illness progression” caused confusion among participants, as “progression” typically implies “positive advancement” in daily life. This was replaced by “illness worsening”. Thirdly, participants expressed a desire for specific information on, for example, supporting one’s children, nutrition and exercise, dealing with work, and psychosocial support and care. Consequently, we added references to specific websites providing information on these topics.

3.2. Evaluation

3.2.1. Study Sample

From September to November 2024, 53 patients joined the evaluation panel. In total, 10 participants withdrew for the following reasons: a lack of access to the website (n = 4), disease worsening (n = 3), a lack of connection to the study (n = 1), technical errors preventing the completion of the follow-up questionnaire (n = 1), or unspecified reasons (n = 1).

Ultimately, 43 participants were included in the quantitative analysis, and 15 participants were included in the qualitative analysis. The 43 participants were aged from 24 to 73 years (M = 57.23, SD = 8.75), and the majority identified as women (n = 29, 67.44%). Most participants were diagnosed with lung cancer (n = 25, 58.14%) and treated with immunotherapy (n = 25). Time since diagnosis varied from 6 to 168 months (M = 45.56, SD = 32.70). Table 3 provides the sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of the participants.

Table 3.

Clinical and sociodemographic characteristics of the evaluation panel.

3.2.2. Psychological Distress and Resilience

In line with our expectations, the results indicated that psychological distress did not change from baseline (M = 13.42, SD = 6.85) to follow-up (M = 13.58, SD = 5.92). The same applied to the ability to manage adversities, which also did not change from baseline (M = 3.66, SD = 0.56) to follow-up (M = 3.50, SD = 0.63).

3.2.3. Design and Usability

One participant did not fully complete the SUS and was, therefore, excluded from the analysis. The average score on the SUS was 70.38. Of the 42 participants, 10 (23.8%) rated the website’s usability as “excellent”, 18 (42.9%) rated the website as “good”, 10 (23.8%) rated the website as “moderate”, and 4 (9.5%) rated the website as “poor”.

Qualitative analysis of open-ended questions and semi-structured interviews also revealed that participants’ opinions on usability were divided in terms of design, user-friendliness, and tone (see Table 4 for an overview of themes and quotes). Regarding design, some participants mentioned that they found the use of colors and illustrations calm and appropriate for the topic, while a few expressed a desire for more color and found the illustrations somewhat childish. User-friendliness was supported by the clear organization of the relevant main themes, although the numerous click-through options sometimes caused participants to lose track of where they were. In terms of the use of language, most participants indicated that the tone and language used on the website were accessible, concise, and personal, while some noted that it occasionally came across as impersonal and directive.

Table 4.

Themes and subthemes divided into positive feedback and suggestions for improvement, and quotes regarding the usability and feasibility of the website.

3.2.4. Feasibility

Qualitative analysis of the open-ended questions and semi-structured interviews revealed four main themes regarding the feasibility of the website that were similar to the guiding principles of the website: (1) acknowledgment and normalization; (2) tailored information; (3) tools; and (4) recommendations to fellow LTRs. Please see Table 4 for themes, subthemes, and quotes.

Acknowledgment and normalization. Participants experienced a strong sense of recognition with themes such as feeling healthy and ill and ongoing uncertainty. Peer experiences, for example, in the form of quotes and portrait videos, made participants feel less alone.

Several areas for improvement regarding recognition and normalization were mentioned by the evaluation panel. For example, in response to the information about the importance of monitoring one’s body, participants desired more acknowledgment. They reported that, due to various physical complaints, it can sometimes be very difficult to monitor your body or notice any changes occurring. Additionally, despite the added referrals as a result of feedback from the user panel, recognition was lacking for the emotions and challenges experienced by LTRs with (young) children. Although participants appreciated the availability of some information, specifically for their close others on the website, they indicated that much more information would be valued.

Tailored information. The referrals, references to research, texts on relevant themes, and animation videos provided the evaluation panel with tailored and relevant information. They noted that the website, through its referrals, had become a repository of information pertinent to LTRs and could be seen as a guide for LTRs. The references to research allowed participants to understand the basis of the website’s information. Specifically, participants mentioned that texts on the psychological impact of a long-term response to treatment, the idea that making practical arrangements about end-of-life care can actually create space to continue living, and the considerations around the ability or desire to work were particularly informative. The animation videos were helpful in conveying information concisely and prompted participants to reflect on their own situation.

Participants noted that certain information could sometimes seem confronting. For example, some participants with an optimistic outlook or those who were doing well preferred not to read about the potential challenges and end-of-life issues. They expressed a desire for information that focused more on living. Additionally, participants indicated a need for more specific information, such as details on medical treatments, sexuality, work, and insurance, information specifically for young LTRs, when and how a psychologist can help, and managing relationships with children. Furthermore, the need for information specifically aimed at close others was again emphasized.

Tools. The website features various practical tools, such as conversation aids, mindfulness exercises, the value task, and tips from psychologists or psychiatrists, which participants greatly appreciated and were eager to use. The existence of the website itself was also seen as supportive, as it provided hope that there were increasing numbers of LTRs living long lives, which helped broaden their perspective and foster an optimistic outlook. LTRs also wanted to use the website to inform their close others about their complex situation. The relevant themes offered LTRs input for reflection or discussion. Some participants mentioned that the website helped them face their reality, whereas they had previously tended to downplay the severity of their situation.

Participants missed the opportunity to interact on the website, such as a forum. They expressed a desire to use the website to connect with fellow LTRs. Additionally, they mentioned that it would be helpful to have a chat function, allowing them to ask questions to various healthcare providers.

Recommending the website to fellow LTRs. In total, 38 participants (88.37%) noted that they would recommend the website to other LTRs. Out of 43 participants, 5 (11.63%) responded with “no comment” or “not applicable”. Five participants (11.63%) cautiously recommended the website, citing concerns that the website might unsettle users by addressing themes (e.g., end-of-life) that users are currently not focused on. The majority, 33 participants (76.74%), stated they would highly recommend the website to other LTRs, highlighting the wealth of information and practical tips that could serve as a guide amidst uncertainty.

Some participants suggested that the website should be made available soon after diagnosis, especially when there is a chance that the patient may become an LTR because the website can serve as a valuable guide through their disease process. Moreover, participants who were LTRs for many years indicated that they had already discovered how to manage these challenges by themselves and did not find the website particularly useful. Yet, others stated that the website could be appropriate at various times, as LTRs engage with different themes at different stages, allowing them to seek out information on the website that meets their needs at any given moment.

3.2.5. Final Adaptations

Based on the comprehensive evaluation, we discussed within the research team which adaptations needed to be made before we officially launched the website. To improve usability, the number of clickable options was further reduced, and various topics were organized into colored sections to enhance the website’s clarity and ease of navigation. All videos on the website were subtitled to improve accessibility. We decided not to provide additional information, for example, about dealing with children, as the website already referred to a center with expertise in this area, and the creators of the website lacked this specific knowledge. Due to privacy legislation and the unavailability of moderators for the website, it was decided not to implement a forum or chat function. After these final adjustments and decisions, the website was officially launched in March 2025.

4. Discussion

The aim of this study was to develop and evaluate an online website with evidence-based information for advanced cancer patients who have obtained a durable response to immunotherapy or targeted therapy in co-creation with patients, psychologists, and service providers according to the Person-Based Approach [11]. Following the planning, design, and development phases, the website underwent a positive evaluation. Participants’ levels of psychological distress and resilience remained stable while using the website. The usability of the website was evaluated as good, and its content was deemed of additional value. The majority of participants indicated they would recommend the website to other LTRs.

As expected, we found no effects of using the website on psychological distress and resilience. This is in line with a meta-analysis, including 23 studies, which found no effect of web-based interventions for advanced cancer patients on anxiety or depression symptoms [22]. They reported that this was possibly due to a lack of personal informatics (i.e., tools that help people collect personally relevant information) [22,23]. Another potential explanation might be the relatively short time frame between website usage and completing the questionnaire. While the website provides various tools aimed at enhancing coping strategies, LTRs need to practice and incorporate these strategies into their daily lives. Although initial learning may take place during website use, applying these techniques may take longer [24]. Furthermore, the lack of psychosocial guidance for website users may hinder their ability to effectively integrate the strategies provided into their daily lives. Research indicates that unguided online interventions are often less effective compared to those that include guidance [25].

In terms of usability, the majority of participants rated the website as good. On average, websites or digital interventions have a similar rating (i.e., an average score of 68 on the System Usability Scale) [26]. For example, research on the creation of a website tailored for end-of-life planning for advanced cancer patients [27] and a study on a recovery application designed for lung cancer patients [10] received a comparable evaluation.

The website was developed based on the principles of acknowledging the challenges faced by LTRs, normalizing their feelings, and providing tailored information and practical tools. Our evaluation indicated that the website acknowledged the psychological impact of living long-term with cancer for LTRs, validating both negative and positive emotions that come with a long-term response, as described in earlier research [1,28]. Additionally, our study highlighted the need to acknowledge the challenges and burdens experienced by close others, confirming findings from a qualitative study showing that partners tend to sacrifice their own needs, impacting their wellbeing and increasing their anxiety [29].

Regarding tailored information, our study showed that LTRs experience ambivalent emotions towards information about end-of-life care and preparation on the website. Similarly to the literature, some LTRs preferred to focus on life instead of the end of life, while others recognized that making arrangements in advance could be helpful [12,30]. Previous studies showed that talking about the end of life improved cancer patients’ quality of life by helping them understand their prognosis and treatment options and, in turn, reduced uncertainty and fear [31]. This underscores the importance of discussing end-of-life matters and ensuring they are handled with sensitivity and care.

Our study demonstrated that LTRs use the website as a tool to explain their complex situations to close others. This aligns with research indicating that LTRs often feel misunderstood [1]. Friends and family often struggle to understand LTRs’ conditions, partly due to the misconception that cancer is either curable or terminal. The fact that LTRs do not always look ill exacerbates these challenges [2]. In addition, the attention of close others often decreases as LTRs live longer, while they still feel a great need for social support [5]. Showing the website to close others helped LTRs explain the challenges they faced were common for their situation, hopefully increasing understanding and support.

4.1. Strengths and Limitations

Our study demonstrates several strengths. Most notably, the website is grounded in extensive prior research conducted by the authors on LTRs [1,12]. Additionally, the website was developed by a multidisciplinary team comprising patients, relatives, patient representatives, therapists, oncologists, and nurse practitioners. This collaborative approach ensured that researchers had a clear understanding of the wishes and needs of LTRs throughout the entire research and development process.

Our results should also be viewed in light of some limitations. Initially, the researchers planned to analyze (1) technical data during the website evaluation, such as the frequency of website visits, button clicks, and video views, and (2) data from a custom-made questionnaire about the extent to which certain topics were adequately covered and tools were offered to help manage related challenges. However, due to incorrect technical settings, the amount of technical data that could be retrieved was limited and unreliable. Moreover, due to programming errors, the quantitative data of the custom-made questionnaire could not be interpreted. As a result, conclusions about the website’s usability had to rely solely on the System Usability Scale scores and qualitative data.

4.2. Implications for Clinical Practice and Research

During brainstorming sessions, feedback discussions with LTRs and therapists, and the evaluation of the website, it became clear that LTRs hoped that the website could facilitate contact with other members. As noted, this feature was not included in the website due to complications with privacy legislation and security. For example, research highlighted the importance of active moderators in creating a secure and supportive environment for individuals to share their personal experiences [9]. This contrasted with our aim to ensure that the website remained accessible and sustainable, requiring minimal manpower to reduce the pressure on healthcare. Nevertheless, the needs of LTRs cannot be ignored, and it is necessary to facilitate more peer contact among LTRs.

The section of the website designed for LTRs is grounded in thorough research. In contrast to this, a significant gap in research remains regarding the coping mechanisms and challenges faced by the close others of LTRs. In the first phase of our study, it already became clear that close others would also need tailored information and support. Conducting further research, such as an interview study, could offer deeper insights and serve as a foundation for refining the section of the website tailored to close others to better align with their wishes and needs.

In the future, there are still challenges in the implementation of the website. It is important to keep healthcare providers, patient associations, and other initiatives informed about the existence of the website. Regularly adding new content may help with this, ensuring that visitors continue to return to the website.

5. Conclusions

Due to new treatment options, the group of patients who live longer with cancer is rapidly growing [7]. While this is promising, many LTRs find it difficult to move forward with their lives after obtaining a long-term response [1,6,12]. To address these challenges, we developed the Dutch website www.doorlevenmetkanker.nl in collaboration with LTRs, healthcare professionals, researchers, and service providers. We identified the key issues (i.e., living with uncertainty, relationships with close others, mourning losses, and adapting to life with cancer) and established the website’s main goals: acknowledging and normalizing the emotions, difficulties, and challenges LTRs face and providing tailored information and practical tools. Through repeated feedback from a user panel, the prototype was further optimized. The usability was largely rated as good to excellent. Interview data indicated that participants experienced recognition through portrait videos and quotes, valued the psycho-education provided via written text and (animated) videos, and made use of the practical tools (e.g., conversation aid and mindfulness exercise), confirming that the main goals of the website were achieved. Following this positive evaluation and some final adjustments, the website was officially launched in March 2025 in the Netherlands.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/curroncol32050284/s1.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.C.Z., M.L.v.d.L., and M.P.J.S.; Methodology, L.C.Z., M.L.v.d.L., and M.P.J.S.; Formal Analysis, L.C.Z. and M.P.J.S.; Investigation, L.C.Z., J.J.K., J.v.d.S., and K.P.M.S.; Resources, M.L.v.d.L. and M.P.J.S.; Data Curation, L.C.Z.; Writing—Original Draft Preparation, L.C.Z.; Writing—Review and Editing, L.C.Z., M.L.v.d.L., J.J.K., J.v.d.S., and M.P.J.S.; Visualization, L.C.Z.; Supervision, M.P.J.S.; Project Administration, L.C.Z.; Funding Acquisition, M.P.J.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The study is part of the IMPRESS project, funded by Dutch Cancer Society, grant-number 12932.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Medical Research Ethics Committee Brabant, the Netherlands: NL85889.028.23 on 19 March 2024.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in this study. Written informed consent was obtained from the patient(s) to publish this paper.

Data Availability Statement

A minimal dataset is available in the Supplementary Material. The qualitative data presented in this study are available upon request from the corresponding author due to the privacy of participants’ information.

Acknowledgments

We thank the scientific advisory board of the IMPRESS project for providing valuable input throughout all development phases. The authors acknowledge all participants. We thank the therapist Annelieke Fleuren for reviewing the website. We thank the Department of Pulmonary Diseases of Radboudumc Nijmegen and the therapists of the Helen Dowling Institute for their assistance in the recruitment of participants. We thank Anke Geerts and Melissa Linders for their assistance in conducting, transcribing, and coding the interviews.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| LTRs | Long-term responders |

| PE | Psycho-education |

| HADS | Hospital Anxiety Depression Scale |

| BRS | Brief Resilience Scale |

| SUS | System Usability Scale |

References

- Zwanenburg, L.C.; Suijkerbuijk, K.P.M.; van Dongen, S.I.; Koldenhof, J.J.; van Roozendaal, A.S.; van der Lee, M.L.; Schellekens, M.P.J. Living in the twilight zone: A qualitative study on the experiences of patients with advanced cancer obtaining long-term response to immunotherapy or targeted therapy. J. Cancer Surviv. 2022, 18, 750–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kolsteren, E.E.M.; Deuning-Smit, E.; Chu, A.K.; van der Hoeven, Y.C.W.; Prins, J.B.; van der Graaf, W.T.A.; van Herpen, C.M.L.; van Oort, I.M.; Lebel, S.; Thewes, B.; et al. Psychosocial Aspects of Living Long Term with Advanced Cancer and Ongoing Systemic Treatment: A Scoping Review. Cancers 2022, 14, 3889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunn, J.; Watson, M.; Aitken, J.F.; Hyde, M.K. Systematic review of psychosocial outcomes for patients with advanced melanoma. Psycho-Oncology 2017, 26, 1722–1731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farland, D.C. New lung cancer treatments (immunotherapy and targeted therapies) and their associations with depression and other psychological side effects as compared to chemotherapy. Gen. Hosp. Psychiatry 2019, 60, 148–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lai-Kwon, J.; Heynemann, S.; Flore, J.; Dhillon, H.; Duffy, M.; Burke, J.; Briggs, L.; Leigh, L.; Mileshkin, L.; Solomon, B.; et al. Living with and beyond metastatic non-small cell lung cancer: The survivorship experience for people treated with immunotherapy or targeted therapy. J. Cancer Surviv. 2021, 15, 392–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kamminga, N.C.; van der Veldt, A.A.; Joosen, M.C.; de Joode, K.; Joosse, A.; Grünhagen, D.J.; Nijsten, T.E.; Wakkee, M.; Lugtenberg, M. Experiences of resuming life after immunotherapy and associated survivorship care needs: A qualitative study among patients with metastatic melanoma. Br. J. Dermatol. 2022, 187, 381–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haslam, A.; Gill, J.; Prasad, V. Estimation of the percentage of US patients with cancer who are eligible for immune checkpoint inhibitor drugs. JAMA Netw. Open 2020, 3, e200423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marshall-McKenna, R.; Kotronoulas, G.; Kokoroskos, E.; Gil Granados, A.; Papachristou, P.; Papachristou, N.; Collantes, G.; Petridis, G.; Billis, A.; Bamidis, P.D.; et al. A multinational investigation of healthcare needs, preferences, and expectations in supportive cancer care: Co-creating the LifeChamps digital platform. J. Cancer Surviv. 2023, 17, 1094–1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timmerman, J.G.; Tönis, T.M.; Weering, M.G.H.D.-V.; Stuiver, M.M.; Wouters, M.W.J.M.; van Harten, W.H.; Hermens, H.J.; Vollenbroek-Hutten, M.M.R. Co-creation of an ICT-supported cancer rehabilitation application for resected lung cancer survivors: Design and evaluation. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2016, 16, 155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olsson, M.; Eliasson, I.; Kautsky, S.; Segerstad, Y.H.A.; Nilsson, S. Co-creation of a digital platform for peer support in a community of adolescent and young adult patients during and after cancer. Eur. J. Oncol. Nurs. 2024, 70, 102589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yardley, L.; Morrison, L.; Bradbury, K.; Muller, I. The Person-Based Approach to Intervention Development: Application to Digital Health-Related Behavior Change Interventions. J. Med. Internet Res. 2015, 17, e30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zwanenburg, L.C.; van der Lee, M.L.; Koldenhof, J.J.; Suijkerbuijk, K.P.M.; Schellekens, M.P.J. What patients with advanced cancer experience as helpful in navigating their life with a long-term response: A qualitative study. Support. Care Cancer 2024, 32, 222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zwanenburg, L.C.; van Roekel, E.; Suijkerbuijk, K.P.M.; Koldenhof, J.J.; Schuurbiers-Siebers, O.C.J.; van der Stap, J.; van der Lee, M.L.; Schellekens, M.P.J. Resilience in advanced cancer patients who obtain a long-term response to immunotherapy or targeted therapy: An Ecological Momentary Assessment study. Ann. Beh. Med. 2025; in press. [Google Scholar]

- Zigmond, A.S.; Snaith, R.P. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 1983, 67, 361–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spinhoven, P.; Ormel, J.; Sloekers, P.P.A.; Kempen, G.I.J.M.; Speckens, A.E.M.; Van Hemert, A.M. A validation study of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) in different groups of Dutch subjects. Psychol. Med. 1997, 27, 363–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, B.W.; Dalen, J.; Wiggins, K.; Tooley, E.; Christopher, P.; Bernard, J. The brief resilience scale: Assessing the ability to bounce back. Int. J. Behav. Med. 2008, 15, 194–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leontjevas, R.; de Beek, W.; Lataster, J.; Jacobs, N. Brief Resilience Scale-Dutch Version [database record]. APA PsycTests 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bangor, A.; Kortum, P.T.; Miller, J.T. An Empirical Evaluation of the System Usability Scale. Int. J. Hum. Comput. Interact. 2008, 24, 574–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ensink, C.J.; Keijsers, N.L.W.; Groen, B.E. Translation and validation of the System Usability Scale to a Dutch version: D-SUS. Disabil. Rehabil. 2024, 46, 395–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Billingham, S.A.; Whitehead, A.L.; Julious, S.A. An audit of sample sizes for pilot and feasibility trials being undertaken in the United Kingdom registered in the United Kingdom Clinical Research Network database. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2013, 13, 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Thematic Analysis: A Practical Guide; SAGE Publications: London, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Kamalumpundi, V.; Saeidzadeh, S.; Chi, N.-C.; Nair, R.; Gilbertson-White, S. The efficacy of web or mobile-based interventions to alleviate emotional symptoms in people with advanced cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Support. Care Cancer 2022, 30, 3029–3042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, Y.A.; Hossain, M.M.; Chou, W.S. Digital interventions to facilitate patient-provider communication in cancer care: A systematic review. Psycho-Oncology 2020, 29, 591–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamama-Raz, Y.; Pat-Horenczyk, R.; Perry, S.; Ziv, Y.; Bar-Levav, R.; Stemmer, S.M. The Effectiveness of Group Intervention on Enhancing Cognitive Emotion Regulation Strategies in Breast Cancer Patients. Integr. Cancer Ther. 2016, 15, 175–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Helmondt, S.J.; van der Lee, M.L.; van Woezik, R.A.M.; Lodder, P.; de Vries, J. No effect of CBT-based online self-help training to reduce fear of cancer recurrence: First results of the CAREST multicenter randomized controlled trial. Psycho-Oncology 2020, 29, 86–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyzy, M.; Bond, R.; Mulvenna, M.; Bai, L.; Dix, A.; Leigh, S.; Hunt, S. System Usability Scale Benchmarking for Digital Health Apps: Meta-analysis. JMIR mHealth uHealth 2022, 10, e37290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walsh, C.A.; Miller, S.J.; Smith, C.B.; Prigerson, H.G.; McFarland, D.; Yarborough, S.; Santos, C.D.L.; Thomas, R.; Czaja, S.J.; RoyChoudhury, A.; et al. Acceptability and usability of the Planning Advance Care Together (PACT) website for improving patients’ engagement in advance care planning. PEC Innov. 2024, 4, 100245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burgers, V.W.G.; Bent, M.J.v.D.; Rietjens, J.A.C.; Roos, D.C.; Dickhout, A.; Franssen, S.A.; Noordoek, M.J.; van der Graaf, W.T.A.; Husson, O. “Double awareness”—Adolescents and young adults coping with an uncertain or poor cancer prognosis: A qualitative study. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 1026090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolsteren, E.E.M.; Deuning-Smit, E.; Prins, J.B.; van der Graaf, W.T.A.; Kwakkenbos, L.; Custers, J.A.E. Perspectives of patients, partners, primary and hospital-based health care professionals on living with advanced cancer and systemic treatment. J. Cancer Surviv. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arantzamendi, M.; García-Rueda, N.; Carvajal, A.; Robinson, C.A. People With Advanced Cancer: The Process of Living Well With Awareness of Dying. Qual. Health Res. 2020, 30, 1143–1155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayashi, Y.; Sato, K.; Ogawa, M.; Taguchi, Y.; Wakayama, H.; Nishioka, A.; Nakamura, C.; Murota, K.; Sugimura, A.; Ando, S. Association Among End-Of-Life Discussions, Cancer Patients’ Quality of Life at End of Life, and Bereaved Families’ Mental Health. Am. J. Hosp. Palliat. Med. 2022, 39, 1071–1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).