Enhancing the Cancer Care Journey for Indigenous Patients: A Guide for Oncology Nurses

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Background and Context

2.1. Inuit and the Cancer Care Journey

2.2. Local Context

3. Methods

3.1. Participants and Recruitment

3.2. Analysis

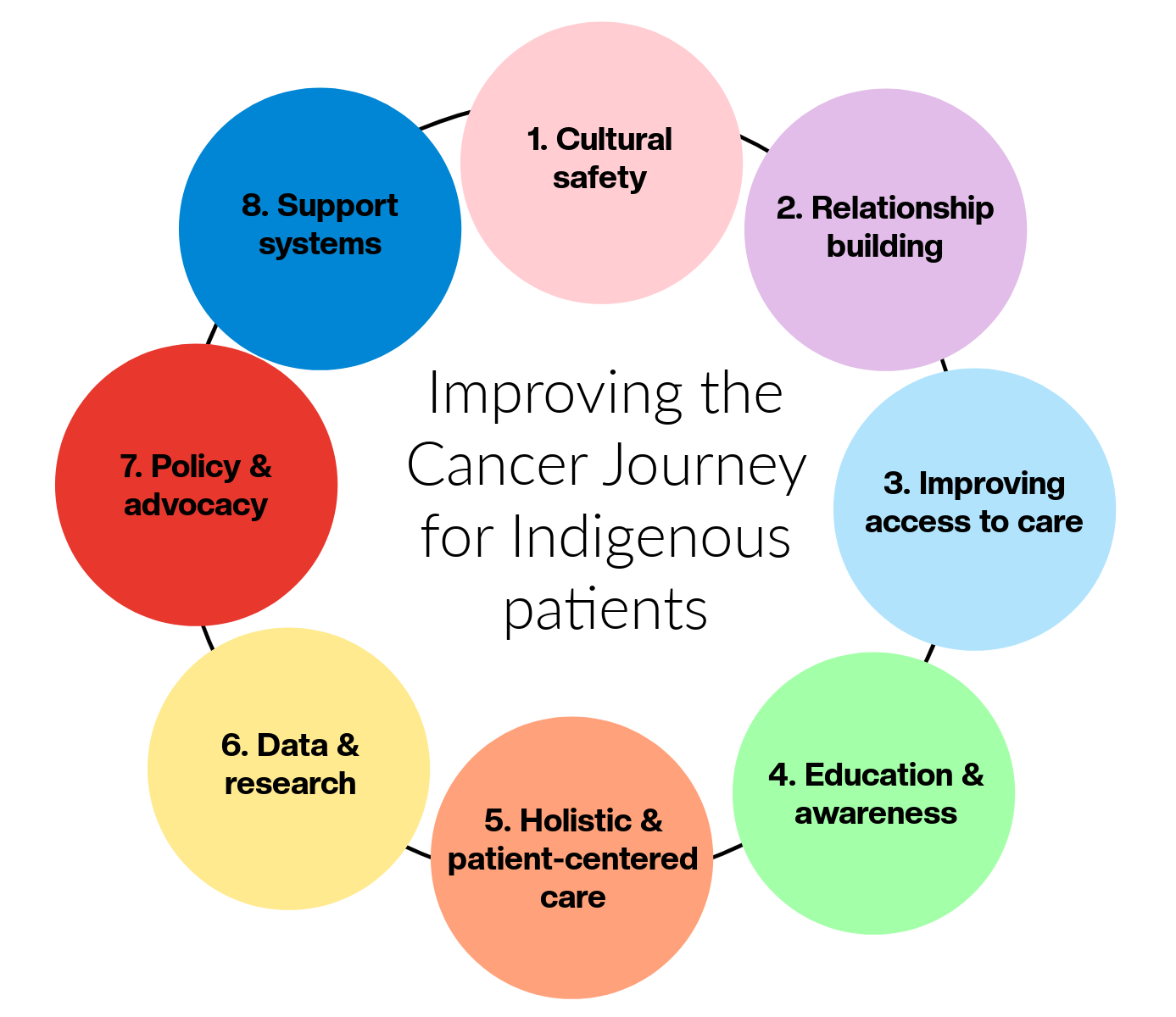

4. Improving the Cancer Care Journey for Indigenous Peoples

4.1. Cultural Competence and Safety

4.2. Building Trust and Relationships

4.3. Access to Care

4.4. Education and Awareness

4.5. Holistic and Patient-Centered Care

4.6. Data and Research

4.7. Policy and Advocacy

4.8. Support Systems

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Statistics Canada. Health of Canada. 2025. Available online: https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/82-570-x/82-570-x2024001-eng.pdf (accessed on 27 February 2025).

- Canadian Cancer Statistics Advisory Committee. Canadian Cancer Statistics 2023; Canadian Cancer Society: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2023; Available online: https://cdn.cancer.ca/-/media/files/research/cancer-statistics/2023-statistics/2023_PDF_EN.pdf (accessed on 27 February 2025).

- Canadian Cancer Statistics Advisory Committee. Canadian Cancer Statistics: A 2024 Special Report on the Economic Impact of Cancer in Canada; Canadian Cancer Society: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2024; Available online: https://cdn.cancer.ca/-/media/files/research/cancer-statistics/2024-statistics/2024-special-report/2024_pdf_en.pdf?rev=ca6616ddd26e4c15a25bdc68457d4c65&hash=5D5FF0B61F28198C7D4948A3D4D37B59 (accessed on 1 March 2025).

- Statistics Canada. Indigenous Peoples Technical Report Census of Population, 2021. 2024. Available online: https://www12.statcan.gc.ca/census-recensement/2021/ref/98-307/98-307-x2021001-eng.pdf (accessed on 4 March 2025).

- Elias, B.; Kliewer, E.V.; Hall, M.; Demers, A.A.; Turner, D.; Martens, P.; Hong, S.P.; Hart, L.; Chartrand, C.; Munro, G. The burden of cancer risk in Canada’s Indigenous population: A comparative study of known risks in a Canadian region. Int. J. Gen. Med. 2011, 4, 699–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Canadian Partnership Against Cancer. Inuit Cancer Control in Canada Baseline Report; Canadian Partnership Against Cancer: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2014; Available online: https://s22457.pcdn.co/wp-content/uploads/2018/12/inuit_cc_baseline_report_EN.pdf (accessed on 1 February 2025).

- Ahmed, S.; Shahid, R.K.; Episkenew, J.A. Disparity in cancer prevention and screening in Aboriginal populations: Recommendations for action. Curr. Oncol. 2015, 22, 417–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Beckett, M.; Cole, K.; White, M.R.; Chan, J.L.; McVicar, J.; Rodin, D.; Clemons, M.; Bourque, J. Decolonizing Cancer Care in Canada. J. Cancer Policy 2021, 30, 100309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, W.Q.; Gifford, W.; Phillips, J.C.; Coburn, V. Examining structural factors influencing cancer care experienced by Inuit in Canada: A scoping review. Int. J. Circumpolar Health 2023, 82, 2253604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beben, N.; Muirhead, N. Improving cancer control in First Nations, Inuit and Métis communities in Canada. Eur. J. Cancer 2016, 25, 219–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Kim, P.J. Social Determinants of Health Inequities in Indigenous Canadians Through a Life Course Approach to Colonialism and the Residential School System. HEQ 2019, 3, 378–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavoie, J.G.; Kaufert, G.; Browne, A.J.; O’Neil, J.D. Managing Matajoosh: Determinants of First Nations’ cancer care decisions. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2016, 16, 402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Grady, J.R.; Ferdus, J.; Leylachian, S.; Bolarinwa, Y.; Wagamese, J.; Ellison, L.K.; Siedule, C.; Batista, R.; Sheppard, A.J. Lung cancer in First Nations, Inuit, and Métis peoples in Canada—A scoping review. Int. J. Circumpolar Health 2024, 83, 2381879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horrill, T.; Lavoie, J.; Martin, D.; Schultz, A. Places & Spaces: A Critical Analysis of Cancer Disparities and Access to Cancer Care Among First Nations Peoples in Canada. Witn. Can. J. Crit. Nurs. Discourse 2020, 2, 104–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oosterveer, T.M.; Young, T.K. Primary health care accessibility challenges in remote Indigenous communities in Canada’s North. Int. J. Circumpolar Health 2015, 74, 29576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jull, J.; Sheppard, A.J.; Hizaka, A.; Barton, G.; Doering, P.; Dorschner, D.; Edgecombe, N.; Ellis, M.K.; Graham, I.D.; Habash, M.; et al. Experiences of Inuit in Canada who travel from remote settings for cancer care and impacts on decision making. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2021, 21, 328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Canadian Partnership Against Cancer. 2019–2029 Canadian Strategy for Cancer Control; Canadian Partnership Against Cancer: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2019; Available online: https://s22457.pcdn.co/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/Canadian-Strategy-Cancer-Control-2019-2029-EN.pdf (accessed on 1 February 2025).

- Chan, J.; Griffiths, K.; Turner, A.; Tobias, J.; Clarmont, W.; Delaney, G.; Hutton, J.; Olson, R.; Penniment, M.; Bourque, J.M.; et al. Radiation Therapy and Indigenous Peoples in Canada and Australia: Building Paths Toward Reconciliation in Cancer Care Delivery. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 2023, 116, 421–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Young, T.L.; Kelly, J.; Friborg, J.; Soininen, L.; Wong, K. Cancer among circumpolar populations: An emerging public health concern. Int. J. Circumpolar Health 2016, 75, 29787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gamelin, R.; Hébert, M.; Tratt, E.; Brassard, P. Ethnographic study of the barriers and facilitators to implementing human papillomavirus (HPV) self-sampling as a primary screening strategy for cervical cancer among Inuit women of Nunavik, Northern Quebec. Int. J. Circumpolar Health 2022, 81, 2032930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, J.; Lanier, A.P.; Santos, M.J.; Healey, S.; Louchini, R.; Friborg, J.; Young, K.; Ng, C. Cancer among the circumpolar Inuit, 1989–2003. II. Patterns and trends. Int. J. Circumpolar Health 2008, 67, 408–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lux, M. Separate Beds: A History of Indian Hospitals in Canada, 1920s–1980s; University of Toronto Press: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Hick, S. The Enduring Plague: How Tuberculosis in Canadian Indigenous Communities is Emblematic of a Greater Failure in Healthcare Equality. J. Epidemiol. Glob. Health 2019, 9, 89–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loppie, C.; Wien, F. Understanding Indigenous Health Inequities Through a Social Determinants Model. National Collaborating Centre for Indigenous Health. 2022. Available online: https://www.nccih.ca/Publications/Lists/Publications/Attachments/10373/Health_Inequalities_EN_Web_2022-04-26.pdf (accessed on 12 February 2025).

- Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami. Social Determinants of Inuit Health in Canada. 2014. Available online: https://www.itk.ca/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/ITK_Social_Determinants_Report.pdf (accessed on 12 February 2025).

- Healey, G. In Under-Served: Health Determinants of Indigenous, Inner-City, and Migrant Populations in Canada; Arya, A.N., Piggott, T., Eds.; Exploring the development of a health care model based on Inuit wellness concepts as part of self-determination and improving wellness in Northern communities. Canadian Scholars Press: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2018; pp. 92–104. ISBN 978-1773380582. [Google Scholar]

- Carr, T.; Arcand, L.; Roberts, R.; Sedgewick, J.; Ali, A.; Groot, G. The experiences of Indigenous people with cancer in Saskatchewan: A patient-oriented qualitative study using a sharing circle. CMAJ 2025, 8, E852–E859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada. Calls to Action. 2015. Available online: http://www.trc.ca/websites/trcinstitution/File/2015/Findings/Calls_to_Action_English2.pdf (accessed on 12 February 2025).

- Whiting, B. Community-led investigations of unmarked graves at Indian residential schools in Western Canada—Overview, status report and best practices. Archaeol. Prospect. 2024, 31, 403–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brascoupé, S.; Waters, C. Cultural Safety Exploring the Applicability of the Concept of Cultural Safety to Aboriginal Health and Community Wellness. IJIH 2009, 5, 6–41. [Google Scholar]

- Curtis, E.; Jones, R.; Tipene-Leach, D.; Walker, C.; Loring, B.; Paine, S.J.; Reid, P. Why cultural safety rather than cultural competency is required to achieve health equity: A literature review and recommended definition. Int. J. Equity Health 2019, 18, 174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witham, S.; Carr, T.; Badea, A.; Ryan, M.; Stringer, L.; Barreno, L.; Groot, G. Sâkipakâwin: Assessing Indigenous Cancer Supports in Saskatchewan Using a Strength-Based Approach. Curr. Oncol. 2022, 29, 132–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horrill, T.C.; Martin, D.E.; Lavoie, J.G.; Schultz, A.S.H. A critical exploration of nurses’ perceptions of access to oncology care among Indigenous peoples: Results of a national survey. Nurs. Inq. 2021, 29, 12446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Champ, S.; Dixon, C. Patient navigation in Canada: Directions from the North. Semin. Oncol. Nurs. 2024, 40, 151588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groot, G.; Marques Santos, J.D.; Witham, S.; Leeder, E.; Carr, T. “Somebody That can Meet you on Your Level:” Cancer Survivors’ Perspectives on the Role of Indigenous Patient Navigators in Cancer Care. Can. J. Nurs. Res. 2024, 56, 178–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, L.; Hatala, A.; Ijaz, S.; Courchene, E.D.; Bushie, E.B. Indigenous-led health care partnerships in Canada. CMAJ 2020, 192, E208–E216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyoon Achan, G.; Enib, R.; Kinewd, K.A.; Phillips-Beck, W.; Lavoie, J.G.; Katz, A. The Two Great Healing Traditions: Issues, Opportunities, and Recommendations for an Integrated First Nations Healthcare System in Canada. HS&R 2021, 7, e1943814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galica, J.; Alsius, A.; Sahi, S.; Holmes, J.; Kerr, H.; Bildfell, K.; Patton, L.; Sinasac, C.; Ross-White, A.; Crawford, J. Cancer-related care for rural and remote populations in Canada: A scoping review. CONJ 2025, 35, 3–25. Available online: https://www.canadianoncologynursingjournal.com/index.php/conj/article/view/1553/1244 (accessed on 1 March 2025). [CrossRef]

- The First Nations Information Governance Centre. Ownership, Control, Access and Possession (OCAP™): The Path to First Nations Information Governance Centre; The First Nations Information Governance Centre: Ottawa, OB, Canada, 2014; Available online: https://www.ktpathways.ca/system/files/resources/2019-02/ocap_path_to_fn_information_governance_en_final.pdf (accessed on 1 March 2025).

- Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami. National Inuit Strategy on Research. 2018. Available online: https://www.itk.ca/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/ITK-National-Inuit-Strategy-on-Research.pdf (accessed on 1 March 2025).

- National Aboriginal Health Organization (NAHO). Principles of Ethical Métis Research. 2010. Available online: https://ruor.uottawa.ca/server/api/core/bitstreams/b7376da9-64e7-42e7-a14d-b4101bfe086b/content (accessed on 1 March 2025).

- Horrill, T. Toward equitable access to oncology care for Indigenous Peoples in Canada: Implications for nursing. CONJ 2022, 32, 437–443. [Google Scholar]

- Santos Salas, A.; Bassah, N.; Pujadas Botey, A.; Robson, P.; Beranek, J.; Iyiola, I.; Kennedy, M. Interventions to improve access to cancer care in underserved populations in high income countries: A systematic review. Oncol. Rev. 2024, 18, 1427441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitzpatrick, K.M.; Ody, M.; Goveas, D.; Montesanti, S.; Campbell, P.; MacDonald, K.; Crowshoe, L.; Campbell, S.; Roach, P. Understanding virtual primary healthcare with Indigenous populations: A rapid evidence review. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2023, 23, 303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, K.; Nguyen, M.D.; Rouleau, G.; Azavedo, R.; Srinivasan, D.; Desveaux, L. Understanding how virtual care has shifted primary care interactions and patient experience: A qualitative analysis. J. Telemed. Telecare 2025, 31, 73–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Patient | Family/Caregivers | Healthcare Professionals |

|---|---|---|

| Have you ever participated in any screening initiatives before? | Do you (or have you) help care for someone with cancer? | What is your role in a patient’s cancer journey? |

| Are you aware of any screening tests available in your community? | Are you aware of the patient’s journey to diagnosis? | Are there any experiences you would like to share regarding in caring for a cancer patient? |

| How did you enter the healthcare system? | How were you involved with the patient leading up to a diagnosis? | What are two (2) things that you think works within the system? |

| Were you happy with the services and communication that were provided? | What are two (2) things worked well and that you were happy with? | What are two (2) things you would change to make the process better? |

| What are two (2) things worked well and that you were happy with? | What two (2) things would you have changed to help make the process better? | |

| What two (2) things would you have changed to help make the process better? | Please tell me about the journey. Include what you felt as well. | |

| What supports were available to you? (e.g., stress, uncertainty etc.…) | Is there anything else that you would like me to know? | |

| Is there anything else about your pre-diagnosis cancer journey that you would like me to know? |

| Improvement Area | Definition | Exemplary Quote |

|---|---|---|

| Prolonged investigation | Captures the drawn-out and often fragmented diagnostic journey experienced by Indigenous individuals prior to a formal cancer diagnosis. It encompasses delays, missed diagnoses, and systemic oversight, where patients often felt they were not being taken seriously or were navigating a system unequipped to recognize or address their concerns in a timely manner. | “So he takes this on himself this time to go to the clinic—“I threw up a couple of times and I don’t feel right”. Anyway, the nurse here was a really dedicated nurse…it went to the nurse first time sending him out because she felt there’s something on the go here…they send him back with a chest infection, before the pills run its course, then he encounters some throwing up, then the nurse sends him back out, they send him back with pneumonia…upon the second time he arrived home, six weeks later, we were standing in the church at his funeral. No more than a week after his funeral, the results of his second trip—the real results, I guess, all of them—came back. And one of the results was he had a huge tumor in his stomach. How can this go unnoticed?" |

| Communication | Highlights the role of interpersonal and systemic communication, including both barriers and facilitators. It includes experiences of language differences, medical jargon, stereotyping, and cultural misunderstandings, alongside moments where healthcare providers either enhanced or hindered understanding and trust | “With technology these days, that should not be an issue. They should have access even if it’s online to an interpreter to translate for the doctor and the patient. Just to ensure that the patient does understand because a lot of times the terminology and certain way things are said in context—in Inuktituk and English—are translated totally differently…And with the severity… when it’s imminent that you get the right translation, especially with cancer being that it’s a terminal disease, can be a terminal disease. And to ensure that the patient clearly understands what they’re going to face and what they’re facing. I don’t think there should be a question whether that patient understood.” |

| Travel | Relates to the physical and emotional toll of the travel required to access care. Many Indigenous patients must leave their communities, incurring costs, enduring disruption of family life, and facing logistical challenges that impact timely diagnosis and continuity of care. | “And the resources really need to be visited though because when you go away and there’s everything right there, and I know we’re isolated but we don’t have enough services. You got to go so far away even just to get an appointment for X-Ray. You can go days and days without your family and your work. People can go and get an X-Ray and be off for half an hour. We go away and we’re gone for three days, maybe longer. How come there are no resources on the ground and in the communities, and we are having to go away. Very important. Health care services alone.” |

| Fear and anxiety | Focuses on the emotional burden that precedes diagnosis, such as anticipatory grief, family history of cancer, and trauma linked to past experiences with healthcare. | “A lot floods back because we’ve survived a lot of cancer. And there’s so many more stories and it hasn’t changed a whole lot since I had cancer. And to see people who have been diagnosed terminally, you wonder what they are doing for them when even as survivors, we had to struggle with that and try to deal with it the best way you can. And it really does change who you are. For those that are fighting to the end, I can’t imagine how hard it must be for them. Even just to think of, “Okay I got cancer. What if it gets really bad? I might die from this.” |

| Be your own health advocate | Represents the individual resilience and proactive behaviours needed to navigate an often unresponsive or dismissive healthcare system. It includes recognizing one’s own symptoms, demanding attention, and persisting despite barriers. | “I find that…until you push, and say I’m not leaving here until something is done, then they dismiss you and say well come back in 6 months, if you’re still having the same symptoms, you know we’ll deal with it, we’ll do some more scans, but they don’t really get to the root of it unless you say I’m not leaving without something being done. And most of our people, our people like we don’t do that.” |

| Access and supports | Focuses on the structural availability of healthcare services, including gaps in local care, limited Indigenous-specific services, and navigation challenges. It also includes both the presence and absence of supportive roles, such as patient navigators and community advocates. | “The journey is hard because it’s like trying to navigate and trying to find supports and not knowing who to ask what to do, or what can I do to get better service, you look through all those things because when you try to refer yourself to someone, it comes back. They used to come back to me and say, “You can’t refer yourself. You’ve got to be referred out by a nurse or a doctor”. You can’t win, you couldn’t win at that time, even with something as serious as cancer going on. And my dad, he was in his 50s. They had diagnosed him with pneumonia and sent him out. He never came back. He had lung cancer. But he died after" |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Shea, J.M.; Buckle, T.; Doody, S.; Michelin, K. Enhancing the Cancer Care Journey for Indigenous Patients: A Guide for Oncology Nurses. Curr. Oncol. 2025, 32, 279. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol32050279

Shea JM, Buckle T, Doody S, Michelin K. Enhancing the Cancer Care Journey for Indigenous Patients: A Guide for Oncology Nurses. Current Oncology. 2025; 32(5):279. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol32050279

Chicago/Turabian StyleShea, Jennifer M., Tina Buckle, Sylvia Doody, and Kathy Michelin. 2025. "Enhancing the Cancer Care Journey for Indigenous Patients: A Guide for Oncology Nurses" Current Oncology 32, no. 5: 279. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol32050279

APA StyleShea, J. M., Buckle, T., Doody, S., & Michelin, K. (2025). Enhancing the Cancer Care Journey for Indigenous Patients: A Guide for Oncology Nurses. Current Oncology, 32(5), 279. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol32050279