Using Invitation Letters to Increase HPV Vaccination Among Adult Women

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Group Selection

- Have had zero doses of an approved HPV vaccine;

- At least 20 years old and born in 1997 or later;

- Female sex, as registered with Manitoba Health;

- Valid Manitoba health insurance coverage and a complete Manitoba mailing address.

- Have received one or more doses of an approved HPV vaccine;

- Have had cervical cancer;

- Have had a hysterectomy;

- In active colposcopy treatment.

2.2. Mail-Outs

2.3. Assessing Intervention Response

3. Results

3.1. Cohort Demographics

3.2. Six-Month HPV Vaccine Uptake

3.3. Twelve-Month HPV Vaccine Uptake

3.4. HPV Vaccine Uptake by Geographic Region

4. Discussion

4.1. Main Findings

4.2. Strengths and Limitations

4.3. Future Directions

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- National Advisory Committee on Immunization. Updated Recommendations on Human Papillomavirus (HPV) Vaccines: 9-Valent HPV Vaccine and Clarification of Minimum Intervals Between Doses in the HPV Immunization Schedule; Public Health Agency of Canada: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Canadian Cancer Society. Compare Study. The Attributable Risk of Cancer in Canada. Available online: https://prevent.cancer.ca/ (accessed on 3 July 2024).

- Statistics Canada. Manitoba Population and Dwelling Counts. Focus on Geography Series, 2021 Census of Population. Available online: https://www12.statcan.gc.ca/census-recensement/2021/as-sa/fogs-spg/index.cfm (accessed on 3 July 2024).

- Manitoba Health and Seniors Care. Manitoba’s School Immunization Program: Questions & Answers for Health Care Providers. Government of Manitoba. Available online: https://www.gov.mb.ca/health/publichealth/factsheets/mb_school_imms.pdf (accessed on 3 July 2024).

- Province of Manitoba. Manitoba’s Immunization Program: Vaccines Offered Free-of-Charge. Available online: https://www.gov.mb.ca/health/publichealth/cdc/vaccineeligibility.html (accessed on 3 July 2024).

- Canadian Partnership Against Cancer. Eliminating Cervical Cancer in Canada: Improving HPV Vaccination Rates. Canadian Partnership Against Cancer. Available online: https://www.partnershipagainstcancer.ca/topics/eliminating-cervical-cancer/hpv-vaccination/ (accessed on 3 July 2024).

- Manitoba Health. Annual Report of Immunization Surveillance: Public Health Information Management System. In Manitoba. Available online: https://www.gov.mb.ca/health/publichealth/surveillance/immunization/index.html (accessed on 3 July 2024).

- Canadian Partnership Against Cancer. Eliminating Cervical Cancer in Canada: Progress on HPV vaccination in Canada. Canadian Partnership Against Cancer. Available online: https://www.partnershipagainstcancer.ca/topics/eliminating-cervical-cancer/hpv-vaccination/progress/ (accessed on 8 April 2025).

- CancerCare Manitoba. HPV Vaccine Data in CervixCheck Registry; Unpublished Data; CancerCare Manitoba: Winnipeg, MB, Canada, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Bonfill, X.; Marzo, M.; Pladevall, M.; Martí, J.; Emparanza, J.I. Strategies for increasing women participation in community breast cancer screening. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2001, 1, CD002943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferroni, E.; Camilloni, L.; Jimenez, B.; Furnari, G.; Borgia, P.; Guasticchi, G.; Rossi, P.G. How to increase uptake in oncologic screening: A systematic review of studies comparing population-based screening programs and spontaneous access. Prev. Med. 2012, 55, 587–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jager, M.; Demb, J.; Asghar, A.; Selby, K.; Marquez Mello, E.; Heskett, K.M.; Lieverman, A.J.; Geng, Z.; Bharti, B.; Singh, S.; et al. Mailed Outreach Is Superior to Usual Care Alone for Colorectal Cancer Screening in the USA: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Dig. Dis. Sci. 2019, 64, 2489–2496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Staley, H.; Shiraz, A.; Shreeve, N.; Bryant, A.; Martin-Hirsch, P.P.; Gajjar, K. Interventions targeted at women to encourage the uptake of cervical screening. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2021, 2021, 1465–1858. [Google Scholar]

- Dougherty, M.K.; Brenner, A.T.; Crockett, S.D.; Gupta, S.; Wheeler, S.B.; Coker-Schwimmer, M.; Cubillos, L.; Malo, T.; Reuland, D.S. Evaluation of Interventions Intended to Increase Colorectal Cancer Screening Rates in the United States: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. JAMA Intern. Med. 2018, 178, 1645–1658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Camilloni, L.; Ferroni, E.; Cendales, B.J.; Pezzarossi, A.; Furnari, G.; Borgia, P.; Guasticchi, G.; Rossi, P.G.; the Methods to increase participation Working Group. Methods to increase participation in organised screening programs: A systematic review. BMC Public Health 2013, 13, 464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vann, J.C.J.; Jacobson, R.M.; Coyne-Beasley, T.; Asafu-Adjei, J.K.; Szilagyi, P.G. Patient reminder and recall interventions to improve immunization rates. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2018, 2018, CD003941. [Google Scholar]

- Szilagyi, P.G.; Bordley, C.; Vann, J.C.; Chelminski, A.; Kraus, R.M.; Margolis, P.A.; Rodewald, L.E. Effect of Patient Reminder/Recall Interventions on Immunization Rates: A Review. JAMA 2000, 284, 1820–1827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Cervical Cancer Elimination Initiative. World Health Organization. Available online: https://www.who.int/initiatives/cervical-cancer-elimination-initiative (accessed on 3 July 2024).

| Control Group (No Study-Specific Letters) | Intervention Group I: Invitation Letter | Intervention Group II: Invitation Letter and Reminder Letter | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Average age Age range | 23.1 years 20–26 years | 23.1 years 20–26 years | 23.2 years 20–26 years |

| Living in a rural region of the province | 23.4% | 24.4% | 25.5% |

| Unscreened for cervical cancer * | 72.8% | 74.3% | 72.7% |

| Control Group (No Study-Specific Letters) | Intervention Group I: Invitation Letter | Intervention Group II: Invitation Letter and Reminder Letter | |

|---|---|---|---|

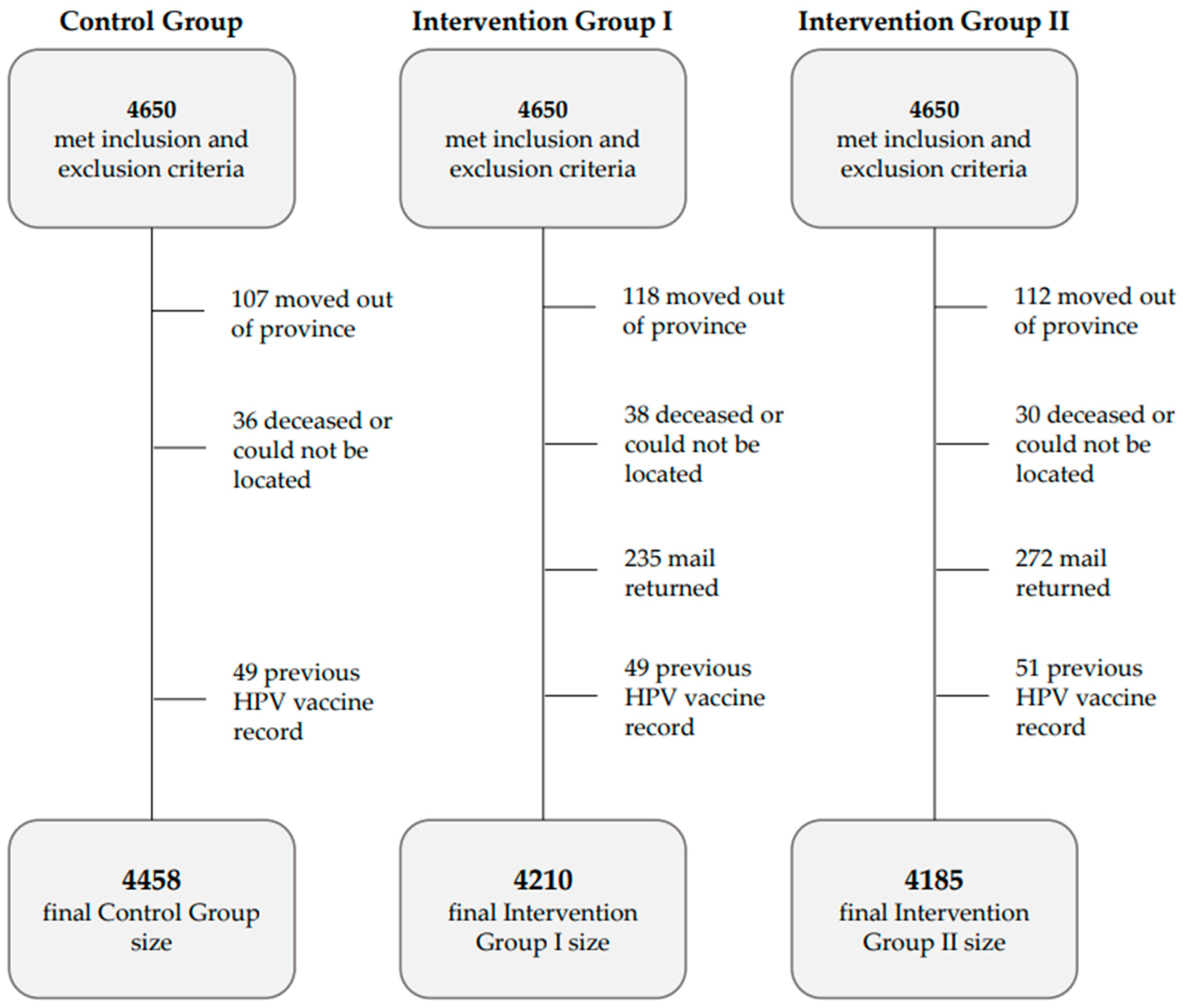

| Group size (met inclusion and exclusion criteria over six months of follow-up) | 4458 | 4210 | 4185 |

| Received one dose of the HPV vaccine within six months of invitation sent date | 38 (0.9%) | 107 (2.5%) | 168 (4.0%) |

| 95% confidence interval | 0.6–1.1% | 2.1–3.0% | 3.4–4.6% |

| p-value | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 |

| Control Group vs. Intervention group I: Invitation Letter | Control Group vs. Intervention Group II: Invitation and Reminder Letters | |

|---|---|---|

| Odds ratio estimates | 3.0 | 4.9 |

| 95% Wald confidence limits | 2.1–4.4 | 3.4–6.9 |

| p-value | <0.0001 | <0.0001 |

| Control Group (No Study-Specific Letters) | Intervention Group I: Invitation Letter | Intervention Group II: Invitation Letter and Reminder Letter | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Group size (met inclusion and exclusion criteria) over 12 months of follow-up | 4430 | 4191 | 4167 |

| Received one dose of the HPV vaccine within twelve months of invitation sent date | 74 (1.7%) | 157 (3.7%) | 215 (5.2%) |

| 95% confidence interval | 1.3–2.1% | 3.2–4.3% | 4.5–5.8% |

| p-value | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 |

| Control Group vs. Intervention Group I: Invitation Letter | Control Group vs. Intervention Group II: Invitation and Reminder Letters | |

|---|---|---|

| Odds ratio estimates | 2.3 | 3.2 |

| 95% Wald confidence limits | 1.7–3.0 | 2.5–4.2 |

| p-value | <0.0001 | <0.0001 |

| Within 6 Months of Invitation | Control Group (No Study-Specific Letters) | Intervention Group I: Invitation Letter | Intervention Group II: Invitation Letter and Reminder Letter |

|---|---|---|---|

| Urban residents | 3417 | 3183 | 3117 |

| Received one dose of the HPV vaccine within 6 months of invitation | 33 (1.0%) | 89 (2.8%) | 147 (4.7%) |

| Rural residents | 1041 | 1027 | 1068 |

| Received one dose of the HPV vaccine within 6 months of invitation | 5 (0.5%) | 18 (1.8%) | 21 (2.0%) |

| p-value | 0.1358 | 0.0647 | <0.0001 |

| Within 12 months of invitation | Control Group (No Study-Specific Letters) | Intervention Group I: Invitation Letter | Intervention Group II: Invitation Letter and Reminder Letter |

| Urban residents | 3392 | 3168 | 3104 |

| Received one dose of the HPV vaccine within 12 months of invitation | 63 (1.9%) | 127 (4.0%) | 178 (5.7%) |

| Rural residents | 1038 | 1023 | 1063 |

| Received one dose of the HPV vaccine within 12 months of invitation | 11 (1.1%) | 30 (2.9%) | 37 (3.5%) |

| p-value | 0.0794 | 0.1150 | 0.0041 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bunzeluk, K.; Coulter, L.; Turner, D.; Jeong, C.; Krueger, C.; Hill, A. Using Invitation Letters to Increase HPV Vaccination Among Adult Women. Curr. Oncol. 2025, 32, 216. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol32040216

Bunzeluk K, Coulter L, Turner D, Jeong C, Krueger C, Hill A. Using Invitation Letters to Increase HPV Vaccination Among Adult Women. Current Oncology. 2025; 32(4):216. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol32040216

Chicago/Turabian StyleBunzeluk, Kelly, Laura Coulter, Donna Turner, Chaeyoon Jeong, Carla Krueger, and Austin Hill. 2025. "Using Invitation Letters to Increase HPV Vaccination Among Adult Women" Current Oncology 32, no. 4: 216. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol32040216

APA StyleBunzeluk, K., Coulter, L., Turner, D., Jeong, C., Krueger, C., & Hill, A. (2025). Using Invitation Letters to Increase HPV Vaccination Among Adult Women. Current Oncology, 32(4), 216. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol32040216