The Extent to Which Artificial Intelligence Can Help Fulfill Metastatic Breast Cancer Patient Healthcare Needs: A Mixed-Methods Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

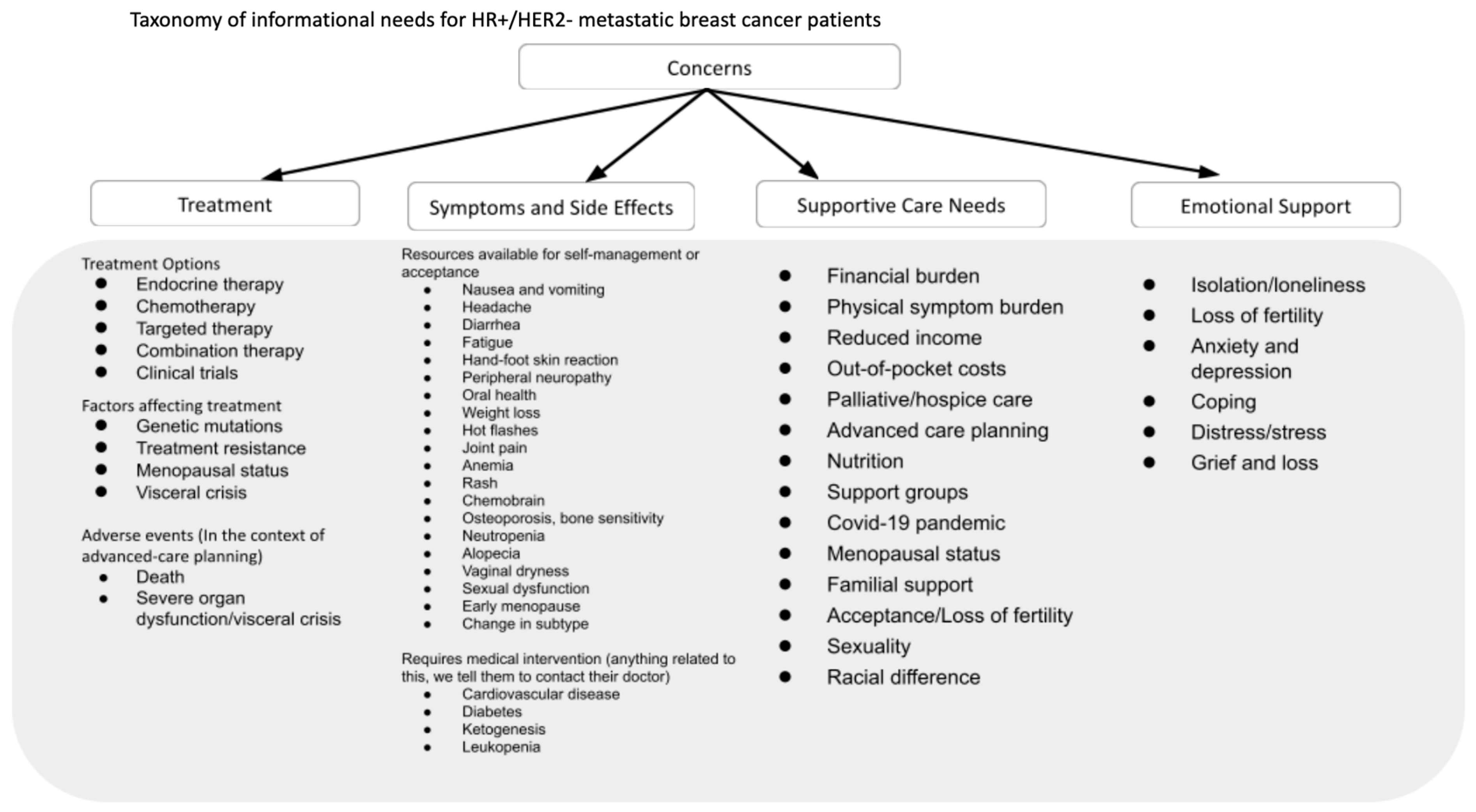

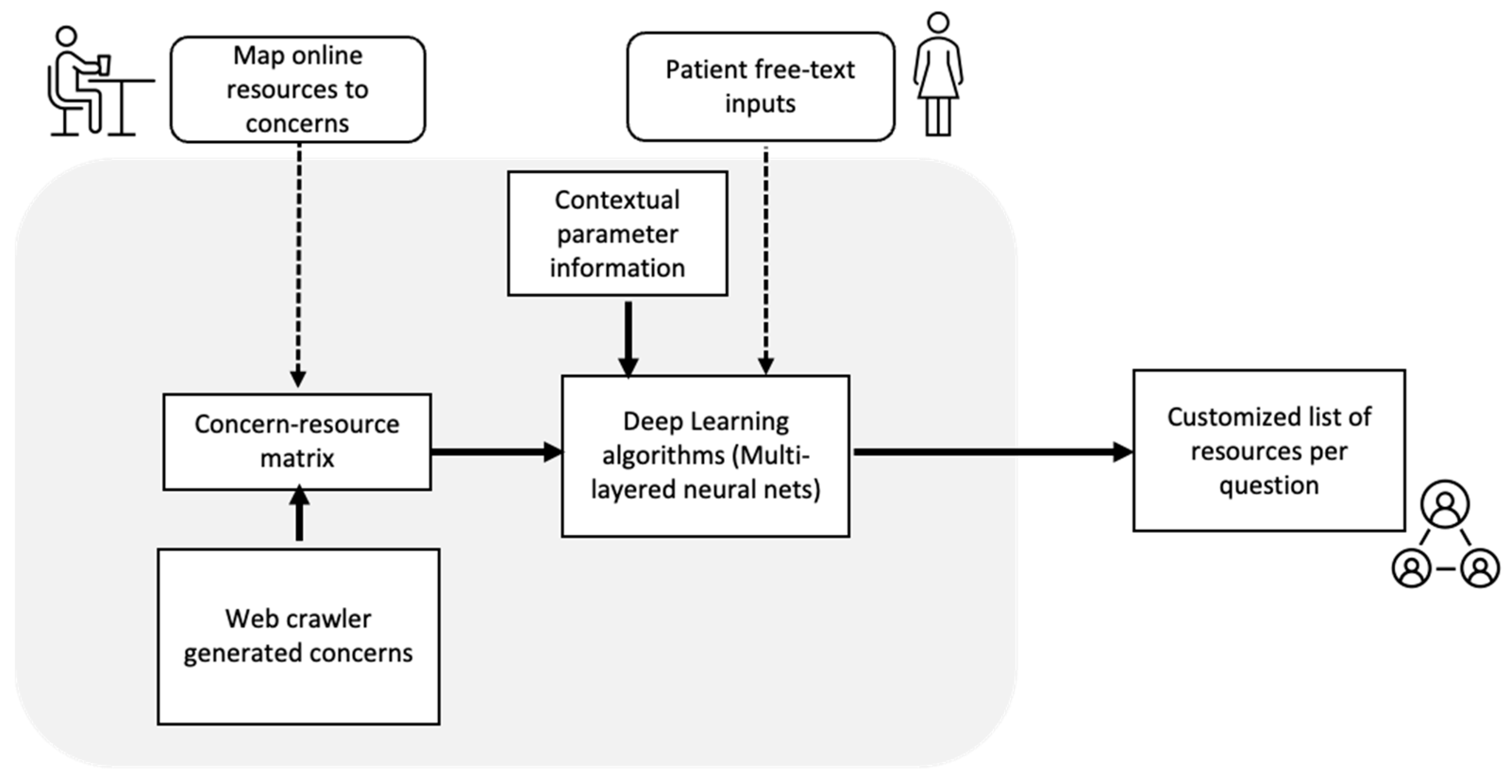

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

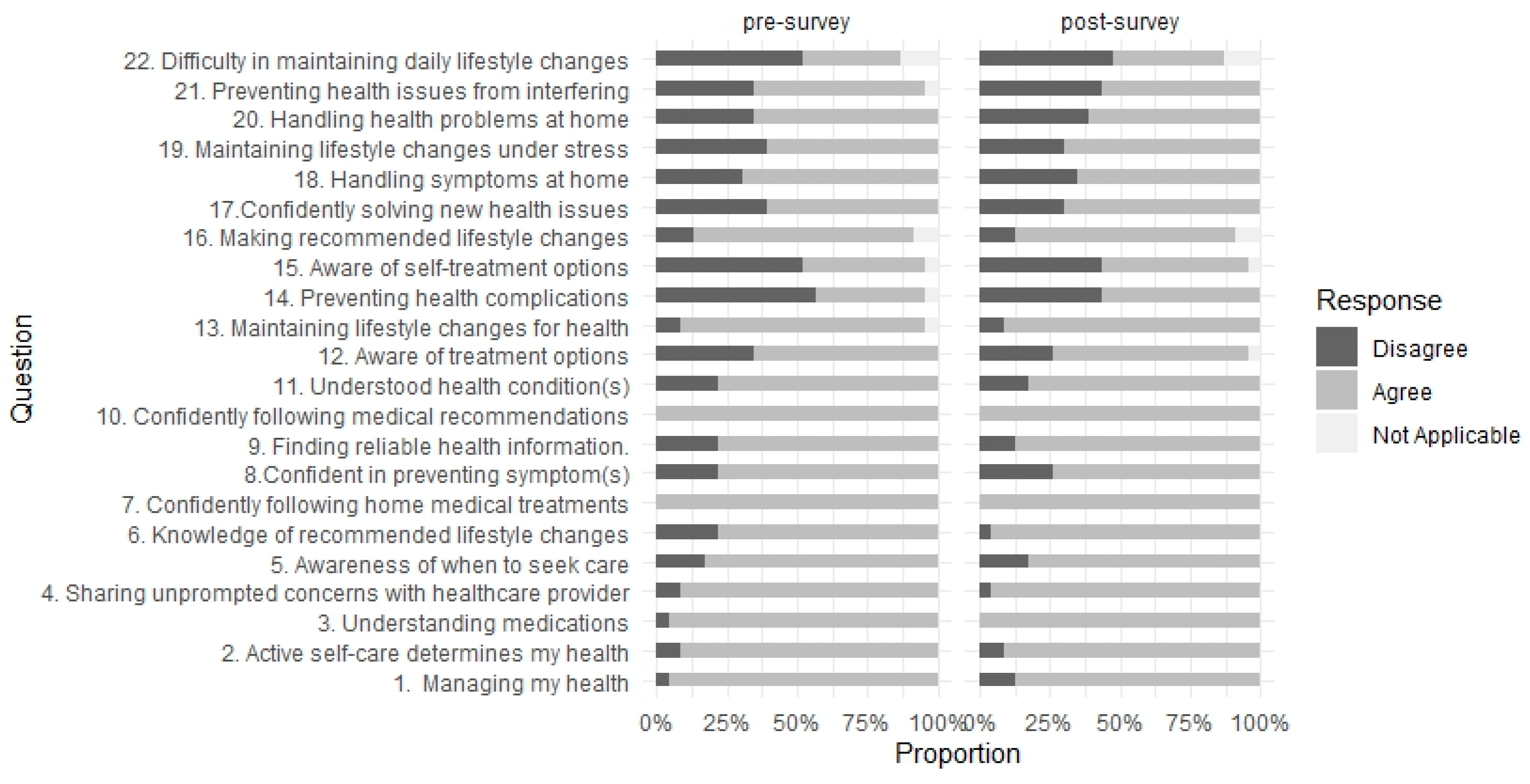

3.1. Quantitative Findings

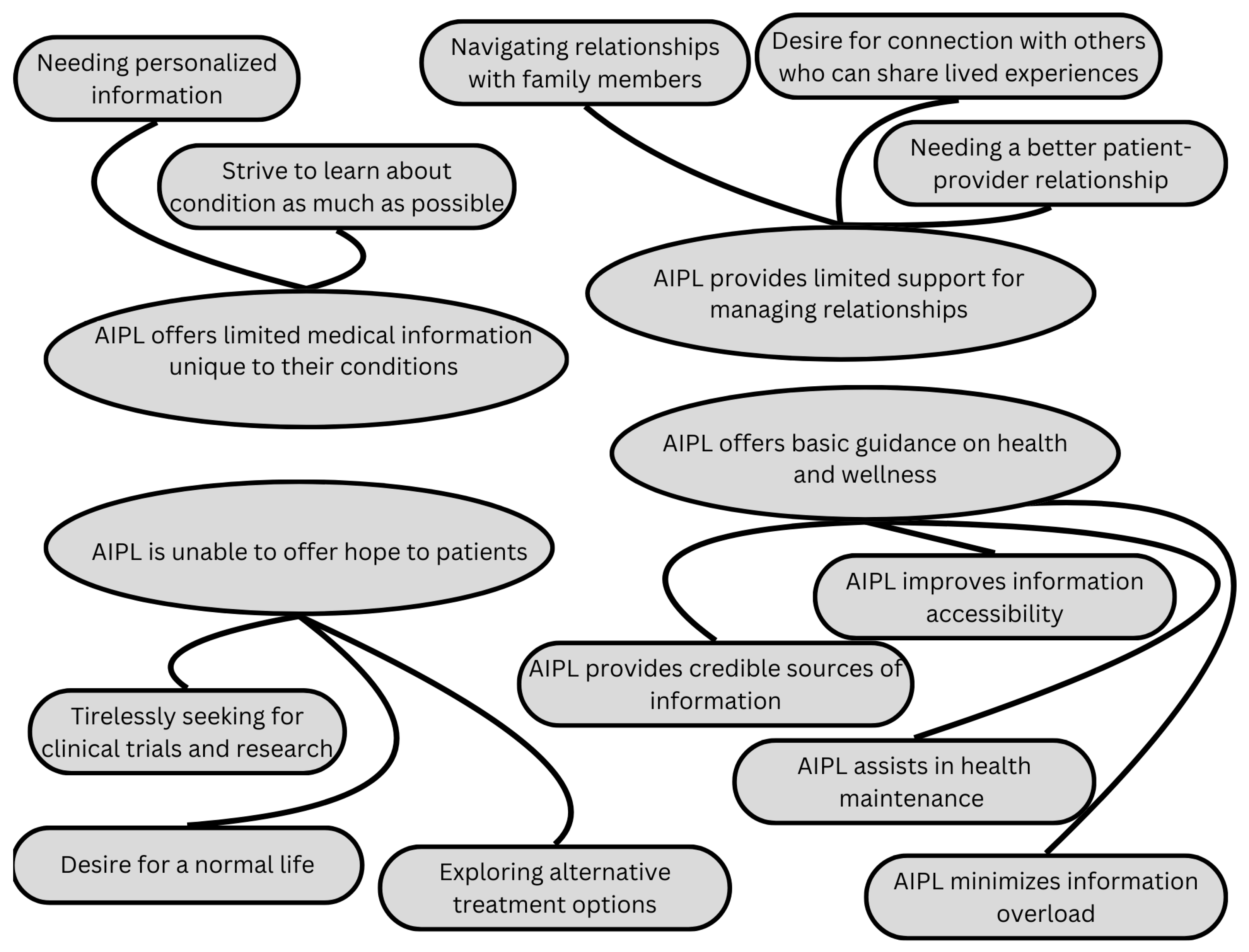

3.2. Qualitative Findings

3.2.1. AIPL Offers Basic Guidance on Wellness and Health

“What I think is the best thing is that it is vetted information. Nowadays on the web, you can find anything and you don’t know if it’s a reliable source. So coming from you, you know that it’s already been reviewed and that it is correct and scientific and that it’s approved and current information…like I think the thing with the chatbot is like, you choose to investigate that topic, so it’s not like it’s forced up on you” (Participant ID 24).

“I was looking at stats a lot when I was first diagnosed and wanted to know the prognosis and how common this is and that…To have something like this is a great resource, to look things up when you need to…I would use it more when first diagnosed than now just because a lot of the stuff that I ran into I already know…I was diagnosed 8 years ago…” (Participant ID 35).

“I remember thinking I was happy…I think I mentioned to you that one of the categories I was really happy to see was the one on spiritual care…just being able to talk about things…When I was in the hospital, I had spiritual people visit me a couple of times and it was just very soothing. I ran into one of them last week, actually Princess Margaret…and it was just great to reconnect with her…Anyway, anything like that, spiritual, and it doesn’t have to be religious, but just the idea of talking about things on a broader perspective is very helpful” (Participant ID 35).

“I was also searching, I’ve been having like serious sleep issues. So I typed in some insomnia and it gave me some information and then said, cognitive behavioural therapy, there’s a manual click here for the manual using the link” (Participant ID 34).

“…expanding on some of the questions…intimacy and sex after breast cancer…for a lot of women that are put into chemically induced menopause and also vaginal atrophy and decreased libido. Generally speaking, we have treatment that is hormone-based, lubricant, or even taking hormones, and many of us are not able to do that…I know this is a really really big hot topic and also about body comfort too” (Participant ID 24).

3.2.2. AIPL Provides Limited Support for Managing Relationships

“The reference to organizations like Wellspring, I was really happy to see because they really were a lifesaver to me when I was just diagnosed” (Participant ID 35).

“If the chatbot can provide a list of lesser-known support groups or if a chatbot could offer me transcripts or online forum…” (Participant ID 29).

“…how to handle people in your life that are dealing with you, caregivers and friends…they’re so upset still, but my mother is just flipped out of the smallest little thing. So I’m not telling her. More support in that area…” (Participant ID 35).

“And for years afterward, I went to a relaxation session every Friday for about 5–6 years. And then they closed the downtown location…It’s a bit of a pain to get there, but the woman who runs the session, she’s just amazing. I can’t say enough about her, so I would follow her anywhere” (Participant ID 35).

“Obviously you should talk to your doctor, but not everybody wants to talk to the doctor first…they don’t know how to initiate it…So they might want the information first because they don’t want to talk to the doctor until they at least have specific questions or made a choice” (Participant ID 24).

“Here’s an example: When I go to my oncologist and I say, what can I do? He says nothing. This is the drug you are taking. Then I go to a naturopath or dietitian and ask what can I do? Okay, you can take this food. You can try this. And that is licensed as well. So between nothing and doing something, we all prefer to do something because we are in control in this case” (Participant ID 11).

“But for me…I would want to see a chat where people can, If I want to chat and say, ‘Has anyone experience example of sleep insomnia’, and then [someone] comes up and say ‘ohh yes’ and then I can talk to someone who might have the same experience as I and in the same illness…as right now I’m single at home” (Participant ID 59).

“I think in the chatbot there could be something about some anecdotal. Could people say their experiences like that? So people can have a frame of reference. You wonder what other people are experiencing? How are they dealing with their thing? So I started going to chat groups…that’s how I learned, what everyone else is dealing with that helped me…That’s what people are looking for when they’re first diagnosed, a frame of reference…What’s normal, what’s not?…What can I expect?” (Participant ID 35).

3.2.3. AIPL Offers Limited Medical Information Unique to Patient Conditions

“The chatbot has a lot of information, but honestly, people like me that like to research, we know it because you go to the sites and to all the resources that we have in this journey. So it was nothing new that I learned…I didn’t find it especially useful because I’ve already knew most of what it answered. It didn’t go beyond what I know…” (Participant ID 45).

“I find I’m a little bit of an outlier everywhere because my situation seems different from everybody else’s…I was told only 3% of the people have a de novo diagnosis, and I have been sent all kinds of possible studies and I never qualify because I’ve not had these other treatments…I’m a bit relieved I didn’t have these very harsh treatments” (Participant ID 29).

3.2.4. AIPL Is Unable to Bring Hope or Excitement to Patients

“I guess what I search for and couldn’t find is anything about clinical trials…I’d like to know what’s next? What’s available…is it something that’s rolled out already FDA approved? Is it something that’s still in trial? What are those trails? How do you know what kind? How effective are those?…I think it’s important to give people with metastatic cancer a little bit of hope that there are the next generation of drugs that are coming out that could be helpful” (Participant ID 34).

“All of a sudden there is a brand new treatment that’s just been approved for my cancer. Luckily, my doctor told me but I might have found out earlier with the chatbot, which is really exciting news because it’s proving to be really effective—just the last two times she [the doctor] has told me about new studies and new trials and they’re really relevant to me because they are about drugs that I’m on…” (Participant ID 25).

“But then maybe we can get that type of drug, it’s for that mutation, for that type of cancer. That is the side effects, it can be the progression, survival, whatever those kinds of things will be very helpful because this is what we are expecting, unfortunately, we are living with this disease. what we want is more treatments to live…the more we know and find out about what is available out there, it’s better you know?” (Participant ID 45).

“And for me having a normal life before you know, I was diagnosed a year ago and I wanted to travel. That was in my cards. I want to travel. I don’t know what I can do and so just ordinary lifestyle topics…I don’t have kids, but if you have children, what are the things you need to…How do you talk to your kids about this? Can you travel safely? Travel tips for example. So I do my own research, but if you’re looking for something that’s a one stop then maybe adding these topics” (Participant ID 34).

“On one level, little things don’t bother me anymore, like being stuck in a lineup. Little things that people experience on a daily basis, nothing like that bothers me at all now. But if something goes wrong, even the slightest problem (related to the disease)…I’m just in a panic…it’s crazy. I think anything to do with anxiety and alleviating anxiety is just wonderful” (Participant ID 35).

“And I think what I love about your idea is that some of that is just basic things for a day-to-day living perspective…they are practical considerations…if I’m doing something that isn’t good for me, I would love to know that and if somebody asked me why…then provide me with an alternative that is good for me…” (Participant ID 25).

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

References

- Willis, K.; Lewis, S.; Ng, F.; Wilson, L. The Experience of Living With Metastatic Breast Cancer—A Review of the Literature. Health Care Women Int. 2015, 36, 514–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kadravello, A.; Tan, S.-B.; Ho, G.-F.; Kaur, R.; Yip, C.-H. Exploring Unmet Needs from an Online Metastatic Breast Cancer Support Group: A Qualitative Study. Med. Kaunas. Lith. 2021, 57, 693. [Google Scholar]

- Krigel, S.; Myers, J.; Befort, C.; Krebill, H.; Klemp, J. “Cancer changes everything!” Exploring the lived experiences of women with metastatic breast cancer. Int. J. Palliat. Nurs. 2014, 20, 334–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Widmark-Jensen, E.; Bernhardsson, S.; Eriksson, M.; Hallberg, H.; Jepsen, C.; Jivegård, L.; Liljegren, A.; Petzold, M.; Svensson, M.; Wärnberg, F.; et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis of risks and benefits with breast reduction in the public healthcare system: Priorities for further research. BMC Surg. 2021, 21, 343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundquist, D.M.; Berry, D.L.; Boltz, M.; DeSanto-Madeya, S.A.; Grace, P.J. Wearing the Mask of Wellness: The Experience of Young Women Living With Advanced Breast Cancer. Oncol. Nurs. Forum. 2019, 46, 329–337. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Wang, T.; Molassiotis, A.; Chung, B.P.M.; Tan, J.-Y. Unmet care needs of advanced cancer patients and their informal caregivers: A systematic review. BMC Palliat. Care 2018, 17, 96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corn, B.W.; Feldman, D.B.; Wexler, I. The science of hope. Lancet Oncol. 2020, 21, e452–e459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ginter, A.C. “The day you lose your hope is the day you start to die”: Quality of life measured by young women with metastatic breast cancer. J. Psychosoc. Oncol. 2020, 38, 418–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gheisari, M.; Ghaderzadeh, M.; Li, H.; Taami, T.; Fernández-Campusano, C.; Sadeghsalehi, H.; Abbasi, A.A. Mobile Apps for COVID-19 Detection and Diagnosis for Future Pandemic Control: Multidimensional Systematic Review. JMIR mHealth uHealth 2024, 12, e44406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghaderzadeh, M.; Shalchian, A.; Irajian, G.; Sadeghsalehi, H.; Zahedi Bialvaei, A.; Sabet, B. Artificial Intelligence in Drug Discovery and Development Against Antimicrobial Resistance: A Narrative Review. Iran. J. Med. Microbiol. 2024, 18, 135–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shortliffe, E.H.; Sepúlveda, M.J. Clinical Decision Support in the Era of Artificial Intelligence. JAMA 2018, 320, 2199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaix, B.; Guillemassé, A.; Nectoux, P.; Delamon, G.; Brouard, B. Vik: A Chatbot to Support Patients with Chronic Diseases. Health 2020, 12, 804–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siglen, E.; Vetti, H.H.; Lunde, A.B.F.; Hatlebrekke, T.A.; Strømsvik, N.; Hamang, A.; Hovland, S.T.; Rettberg, J.W.; Steen, V.M.; Bjorvatn, C. Ask Rosa—The making of a digital genetic conversation tool, a chatbot, about hereditary breast and ovarian cancer. Patient Educ. Couns. 2022, 105, 1488–1494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greer, S.; Ramo, D.; Chang, Y.-J.; Fu, M.; Moskowitz, J.; Haritatos, J. Use of the Chatbot “Vivibot” to Deliver Positive Psychology Skills and Promote Well-Being Among Young People Afteaar Cancer Treatment: Randomized Controlled Feasibility Trial. JMIR mHealth uHealth 2019, 7, e15018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leung, Y.; Ng, S.; Duan, L.; Lam, C.; Chan, K.; Gancarz, M.; Rennie, H.; Trachtenberg, L.; Chan, K.P.; Adikari, A.; et al. Building an Artificial Intelligence Based Co-Facilitator (AICF) for Cancer Online Support Groups: Therapist Feedback and Implications for Adoption. JMIR Cancer 2023, 9, e40113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hibbard, J.H.; Stockard, J.; Mahoney, E.R.; Tusler, M. Development of the Patient Activation Measure (PAM): Conceptualizing and Measuring Activation in Patients and Consumers: Development of the Patient Activation Measure (PAM). Health Serv. Res. 2004, 39, 1005–1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roesel, I.; Froehlich, D.; Joos, S.; Valentini, J.; Mauch, H.; Martus, P. The Patient Activation Measure-13 (PAM-13) in an oncology patient population: Psychometric properties and dimensionality evaluation. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2024, 22, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cella, D.F.; Tulsky, D.S.; Gray, G.; Sarafian, B.; Linn, E.; Bonomi, A.; Silberman, M.; Yellen, S.B.; Winicour, P.; Brannon, J. The Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy Scale: Development and Validation of the General Measure. J. Clin. Oncol. Off. J. Am. Soc. Clin. Oncol. 2023, 41, 5335–5344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyzy, M.; Bond, R.; Mulvenna, M.; Bai, L.; Dix, A.; Leigh, S.; Hunt, S. System Usability Scale Benchmarking for Digital Health Apps: Meta-analysis. JMIR mHealth uHealth 2022, 10, e37290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrne, D. A worked example of Braun and Clarke’s approach to reflexive thematic analysis. Qual. Quant. 2022, 56, 1391–1412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghazavi-Khorasgani, Z.; Ashrafi-Rizi, H.; Mokarian, F.; Afshar, M. Health information seeking behavior of female breast cancer patients. J. Educ. Health Promot. 2018, 7, 138. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Lewi, M.; De Pelsmacker, P.; Cauberghe, V. Women’s information preferences, information needs and online interactive information portal engagement in a breast cancer early diagnosis context. J. Commun. Healthc. 2018, 11, 114–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luoma, M.-L.; Hakamies-Blomqvist, L. The meaning of quality of life in patients being treated for advanced breast cancer: A qualitative study. Psychooncology 2004, 13, 729–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- European Comission. Living Guidelines on the Responsible Use of Generative AI in Research [Internet]. 2024. Available online: https://research-and-innovation.ec.europa.eu/document/download/2b6cf7e5-36ac-41cb-aab5-0d32050143dc_en?filename=ec_rtd_ai-guidelines.pdf (accessed on 9 December 2024).

- Mitsi, C.; Tzintziropoulou, E.; Panagiotopoulou, L. My Alma: A Digital App Supporting Metastatic Breast Cancer Patients in Greece. J. Glob. Oncol. 2018, 4, 98s. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tzelves, L.; Manolitsis, I.; Varkarakis, I.; Ivanovic, M.; Kokkonidis, M.; Useros, C.S.; Kosmidis, T.; Muñoz, M.; Grau, I.; Athanatos, M.; et al. Artificial intelligence supporting cancer patients across Europe—The ASCAPE project. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0265127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristics | ||

|---|---|---|

| Age range (years) | n | % |

| 18–39 | 3 | 7.1 |

| 40–64 | 26 | 61.9 |

| 65+ | 2 | 4.8 |

| Do not want to disclose | 11 | 26.1 |

| Mean | SD | |

| Patient Activation Measure (PAM) raw score | 59.33 | 5.19 |

| Normalized PAM score | 78.49 | 16.74 |

| Pre-survey IES-R | 25.69 | 16.75 |

| PRE-survey FACT-B subscales | ||

| Physical well-being (PWB) | 20.22 | 4.81 |

| Social/family well-being (SWB) | 17.97 | 5.55 |

| Emotional well-being (EWB) | 14.30 | 4.13 |

| Functional well-being (FWB) | 16.22 | 5.86 |

| Post-survey System Usability Scale (SUS) | 72.90 | 14.3 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Leung, Y.W.; So, J.; Sidhu, A.; Asokan, V.; Gancarz, M.; Gajjar, V.B.; Patel, A.; Li, J.M.; Kwok, D.; Nadler, M.B.; et al. The Extent to Which Artificial Intelligence Can Help Fulfill Metastatic Breast Cancer Patient Healthcare Needs: A Mixed-Methods Study. Curr. Oncol. 2025, 32, 145. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol32030145

Leung YW, So J, Sidhu A, Asokan V, Gancarz M, Gajjar VB, Patel A, Li JM, Kwok D, Nadler MB, et al. The Extent to Which Artificial Intelligence Can Help Fulfill Metastatic Breast Cancer Patient Healthcare Needs: A Mixed-Methods Study. Current Oncology. 2025; 32(3):145. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol32030145

Chicago/Turabian StyleLeung, Yvonne W., Jeremiah So, Avneet Sidhu, Veenaajaa Asokan, Mathew Gancarz, Vishrut Bharatkumar Gajjar, Ankita Patel, Janice M. Li, Denis Kwok, Michelle B. Nadler, and et al. 2025. "The Extent to Which Artificial Intelligence Can Help Fulfill Metastatic Breast Cancer Patient Healthcare Needs: A Mixed-Methods Study" Current Oncology 32, no. 3: 145. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol32030145

APA StyleLeung, Y. W., So, J., Sidhu, A., Asokan, V., Gancarz, M., Gajjar, V. B., Patel, A., Li, J. M., Kwok, D., Nadler, M. B., Cuthbert, D., Benard, P. L., Kumar, V., Cheng, T., Papadakos, J., Papadakos, T., Truong, T., Lovas, M., & Wong, J. (2025). The Extent to Which Artificial Intelligence Can Help Fulfill Metastatic Breast Cancer Patient Healthcare Needs: A Mixed-Methods Study. Current Oncology, 32(3), 145. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol32030145