Precision Care for Hereditary Urologic Cancers: Genetic Testing, Counseling, Surveillance, and Therapeutic Implications

Simple Summary

Abstract

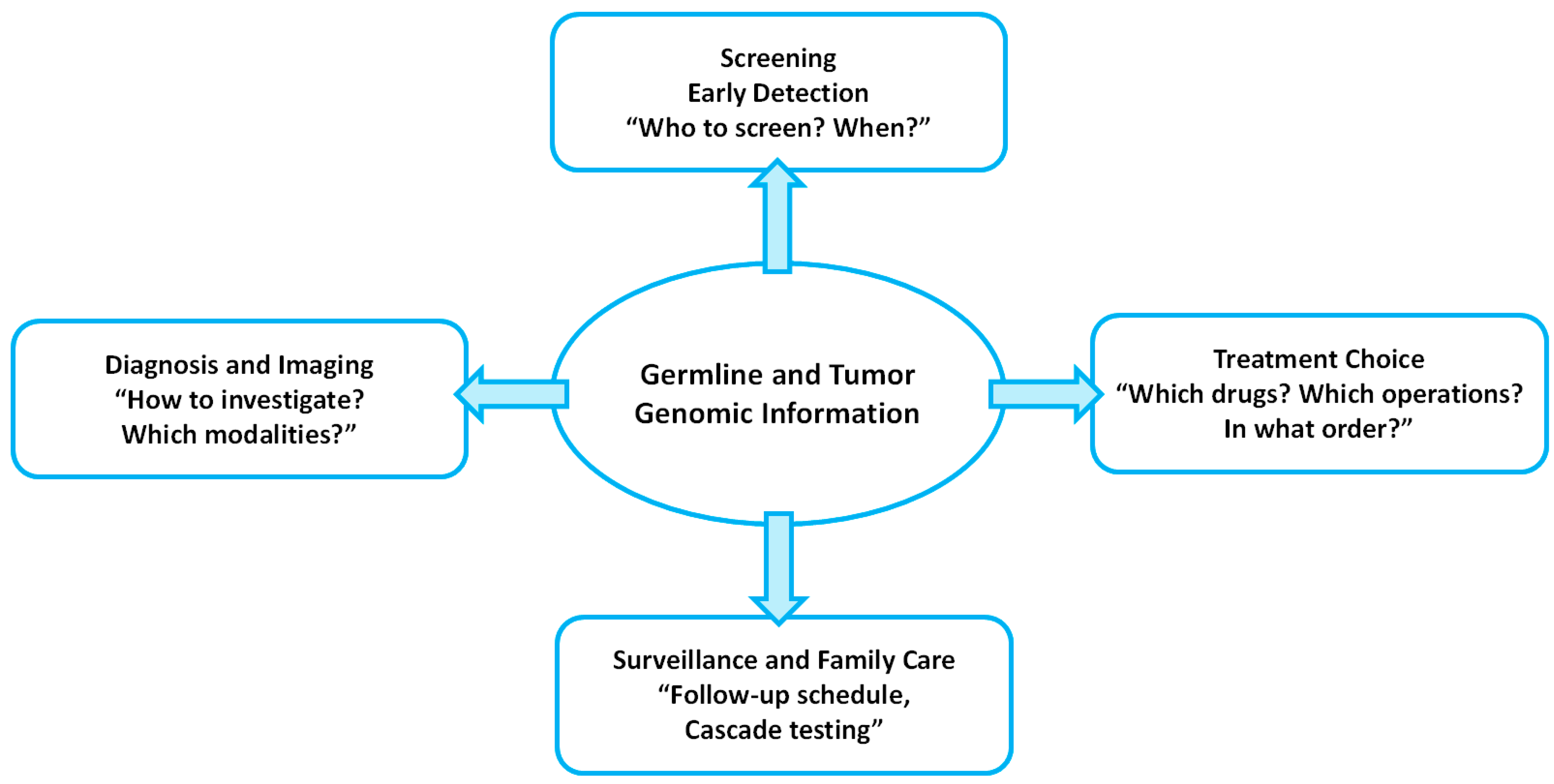

1. Introduction

2. Prostate Cancer

2.1. Genetic Predisposition and Testing Guidelines

2.2. Surveillance and Counseling for Carriers

2.3. Therapeutic Implications

3. RCC and Renal Tumor Predisposition Syndrome (RTPS)

3.1. Overview of Hereditary RCC and RTPS

3.2. Major Hereditary RCC Syndromes and TSC

3.3. Surveillance Strategies for Mutation Carriers

3.4. Treatment Considerations

4. Urothelial Carcinoma (UC)

4.1. UTUC

4.2. Bladder Cancer

5. Pheochromocytoma and Paraganglioma (PPGL)

6. Adrenocortical Carcinoma (ACC)

7. Testicular Germ Cell Tumor (TGCT)

8. Genetic Testing and Counseling in Hereditary Urologic Cancers

8.1. Overview of Germline Testing Technologies and Test Selection

8.2. Pre-Test Counseling Principles

8.3. Post-Test Counseling and Result-Specific Management

8.4. Implementation Strategies for Mainstreaming and Equity

9. Limitations and Future Directions

10. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ACC | adrenocortical carcinoma |

| AML | angiomyolipoma |

| BAP1-TPDS | BAP1 tumor predisposition syndrome |

| BHD | Birt-Hogg-Dubé |

| CNV | Copy-number variant |

| dMMR | deficient mismatch repair |

| EAU | European Association of Urology |

| EMR | electronic medical record |

| GCT | germ cell tumor |

| HLRCC | Hereditary Leiomyomatosis and Renal Cell Carcinoma |

| HPRC | Hereditary Papillary Renal Cell Carcinoma |

| KS | Klinefelter syndrome |

| LAM | lymphangioleiomyomatosis |

| LFS | Li-Fraumeni syndrome |

| MEN2 | Multiple Endocrine Neoplasia type 2 |

| MIBG | metaiodobenzylguanidine |

| MMR | mismatch repair |

| NGS | next-generation sequencing |

| mCRPC | metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer |

| MSI | microsatellite instability |

| OS | overall survival |

| PD-1 | programmed cell death-1 |

| PPGL | pheochromocytoma and paraganglioma |

| PRRT | peptide receptor radionuclide therapy |

| PSA | prostate-specific antigen |

| RCC | renal cell carcinoma |

| rPFS | radiographic progression-free survival |

| SSTR | somatostatin receptor |

| TGCTs | testicular germ cell tumors |

| UC | urothelial carcinoma |

| UTUC | upper tract urothelial carcinoma |

| WES | whole-exome sequencing |

| WGS | whole-genome sequencing |

| VHL | von Hippel–Lindau |

References

- Mucci, L.A.; Hjelmborg, J.B.; Harris, J.R.; Czene, K.; Havelick, D.J.; Scheike, T.; Graff, R.E.; Holst, K.; Möller, S. Nordic Twin Study of Cancer (NorTwinCan) Collaboration. Familial Risk and Heritability of Cancer Among Twins in Nordic Countries. JAMA 2016, 315, 68–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harper, H.L.; McKenney, J.K.; Heald, B.; Stephenson, A.; Campbell, S.C.; Plesec, T.; Magi-Galluzzi, C. Upper tract urothelial carcinomas: Frequency of association with mismatch repair protein loss and lynch syndrome. Mod. Pathol. 2017, 30, 146–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loveday, C.; Law, P.; Litchfield, K.; Levy, M.; Holroyd, A.; Broderick, P.; Kote-Jarai, Z.; Dunning, A.M.; Muir, K.; Peto, J.; et al. Large-scale Analysis Demonstrates Familial Testicular Cancer to have Polygenic Aetiology. Eur. Urol. 2018, 74, 248–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spratt, D.E.; Srinivas, S.; Adra, N.; Ahmed, B.; An, Y.; Bitting, R.; Chapin, B.; Cheng, H.H.; Cho, S.Y.; D’aMico, A.V.; et al. Prostate Cancer, Version 3.2026, NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines In Oncology. J. Natl. Compr. Cancer Netw. 2025, 23, 469–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlo, M.I.; Mukherjee, S.; Mandelker, D.; Vijai, J.; Kemel, Y.; Zhang, L.; Knezevic, A.; Patil, S.; Ceyhan-Birsoy, O.; Huang, K.-C.; et al. Prevalence of Germline Mutations in Cancer Susceptibility Genes in Patients With Advanced Renal Cell Carcinoma. JAMA Oncol. 2018, 4, 1228–1235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Bono, J.; Mateo, J.; Fizazi, K.; Saad, F.; Shore, N.; Sandhu, S.; Chi, K.N.; Sartor, O.; Agarwal, N.; Olmos, D.; et al. Olaparib for Metastatic Castration-Resistant Prostate Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 382, 2091–2102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, D.T.; Uram, J.N.; Wang, H.; Bartlett, B.R.; Kemberling, H.; Eyring, A.D.; Skora, A.D.; Luber, B.S.; Azad, N.S.; Laheru, D.; et al. PD-1 Blockade in Tumors with Mismatch-Repair Deficiency. N. Engl. J. Med. 2015, 372, 2509–2520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antar, R.M.; Fawaz, C.; Gonzalez, D.; Xu, V.E.; Drouaud, A.P.; Krastein, J.; Pio, F.; Murdock, A.; Youssef, K.; Sobol, S.; et al. The Evolving Molecular Landscape and Actionable Alterations in Urologic Cancers. Curr. Oncol. 2024, 31, 6909–6937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shevach, J.W.; Candelieri-Surette, D.; Lynch, J.A.; Hubbard, R.A.; Alba, P.R.; Glanz, K.; Parikh, R.B.; Maxwell, K.N. Racial Differences in Germline Genetic Testing Completion Among Males With Pancreatic, Breast, or Metastatic Prostate Cancers. J. Natl. Compr. Cancer Netw. 2024, 22, 237–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilkens, E.P.; Freije, D.; Xu, J.; Nusskern, D.R.; Suzuki, H.; Isaacs, S.D.; Wiley, K.; Bujnovsky, P.; Meyers, D.A.; Walsh, P.C.; et al. No evidence for a role of BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations in Ashkenazi Jewish fam-ilies with hereditary prostate cancer. Prostate 1999, 39, 280–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ewing, C.M.; Ray, A.M.; Lange, E.M.; Zuhlke, K.A.; Robbins, C.M.; Tembe, W.D.; Wiley, K.E.; Isaacs, S.D.; Johng, D.; Wang, Y.; et al. Germline Mutations in HOXB13 and Prostate-Cancer Risk. N. Engl. J. Med. 2012, 366, 141–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, Z.; Zhu, S.; Zhang, H.; Li, L.; Niu, Y. Germline Homeobox B13 (HOXB13) G84E Mutation and Prostate Cancer Risk in European Descendants: A Meta-analysis of 24 213 Cases and 73 631 Controls. Eur. Urol. 2013, 64, 173–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalampokis, N.; Zabaftis, C.; Spinos, T.; Karavitakis, M.; Leotsakos, I.; Katafigiotis, I.; van der Poel, H.; Grivas, N.; Mitropoulos, D. Review on the Role of BRCA Mutations in Genomic Screening and Risk Stratification of Prostate Cancer. Curr. Oncol. 2024, 31, 1162–1169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacInnis, R.J.; Severi, G.; Baglietto, L.; Dowty, J.G.; Jenkins, M.A.; Southey, M.C.; Hopper, J.L.; Giles, G.G. Population-Based Estimate of Prostate Cancer Risk for Carriers of the HOXB13 Missense Mutation G84E. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e54727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schaeffer, E.M.; Srinivas, S.; Adra, N.; An, Y.; Barocas, D.; Bitting, R.; Bryce, A.; Chapin, B.; Cheng, H.H.; D’aMico, A.V.; et al. Prostate Cancer, Version 4.2023, NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. J. Natl. Compr. Cancer Netw. 2023, 21, 1067–1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, J.T.; Barocas, D.; Carlsson, S.; Coakley, F.; Eggener, S.; Etzioni, R.; Fine, S.W.; Han, M.; Kim, S.K.; Kirkby, E.; et al. Early Detection of Prostate Cancer: AUA/SUO Guideline Part II: Considerations for a Prostate Biopsy. J. Urol. 2023, 210, 54–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pritchard, C.C.; Mateo, J.; Walsh, M.F.; De Sarkar, N.; Abida, W.; Beltran, H.; Garofalo, A.; Gulati, R.; Carreira, S.; Eeles, R.; et al. Inherited DNA-Repair Gene Mutations in Men with Metastatic Prostate Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2016, 375, 443–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicolosi, P.; Ledet, E.; Yang, S.; Michalski, S.; Freschi, B.; O’leary, E.; Esplin, E.D.; Nussbaum, R.L.; Sartor, O. Prevalence of Germline Variants in Prostate Cancer and Implications for Current Genetic Testing Guidelines. JAMA Oncol. 2019, 5, 523–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bancroft, E.K.; Page, E.C.; Castro, E.; Lilja, H.; Vickers, A.; Sjoberg, D.; Assel, M.; Foster, C.S.; Mitchell, G.; Drew, K.; et al. Targeted Prostate Cancer Screening in BRCA1 and BRCA2 Mutation Carriers: Results from the Initial Screening Round of the IMPACT Study. Eur. Urol. 2014, 66, 489–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, E.C.; Bancroft, E.K.; Brook, M.N.; Assel, M.; Hassan Al Battat, M.; Thomas, S.; Taylor, N.; Chamberlain, A.; Pope, J.; Ni Raghallaigh, H.; et al. Interim Results from the IMPACT Study: Evidence for Prostate-specific Antigen Screening in BRCA2 Mutation Carriers. Eur. Urol. 2019, 76, 831–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, H.B.; Helfand, B.; Mamawala, M.; Wu, Y.; Landis, P.; Yu, H.; Wiley, K.; Na, R.; Shi, Z.; Petkewicz, J.; et al. Germline Mutations in ATM and BRCA1/2 Are Associated with Grade Reclassification in Men on Active Surveillance for Prostate Cancer. Eur. Urol. 2019, 75, 743–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiorentino, V.; Martini, M.; Dell’aquila, M.; Musarra, T.; Orticelli, E.; Larocca, L.M.; Rossi, E.; Totaro, A.; Pinto, F.; Lenci, N.; et al. Histopathological Ratios to Predict Gleason Score Agreement between Biopsy and Radical Prostatectomy. Diagnostics 2020, 11, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, J.T.; Barocas, D.; Carlsson, S.; Coakley, F.; Eggener, S.; Etzioni, R.; Fine, S.W.; Han, M.; Kim, S.K.; Kirkby, E.; et al. Early Detection of Prostate Cancer: AUA/SUO Guideline Part I: Prostate Cancer Screening. J. Urol. 2023, 210, 46–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Englman, C.; Barrett, T.; Moore, C.M.; Giganti, F. Active Surveillance for Prostate Cancer. Radiol. Clin. N. Am. 2023, 62, 69–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carll, J.; Bonaddio, J.; Lawrentschuk, N. PSMA PET as a Tool for Active Surveillance of Prostate Can-cer-Where Are We at? J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 3580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bardoscia, L.; Sardaro, A.; Quattrocchi, M.; Cocuzza, P.; Ciurlia, E.; Furfaro, I.; Gilio, M.A.; Mignogna, M.; Detti, B.; Ingrosso, G. The Evolving Landscape of Novel and Old Biomarkers in Localized High-Risk Prostate Cancer: State of the Art, Clinical Utility, and Limitations Toward Precision Oncology. J. Pers. Med. 2025, 15, 367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fallah, J.; Xu, J.; Weinstock, C.; Brave, M.H.; Bloomquist, E.; Fiero, M.H.; Schaefer, T.; Pathak, A.; Abukhdeir, A.; Bhatnagar, V.; et al. FDA Approval Summary: Olaparib in Combination With Abiraterone for Treatment of Patients With BRCA-Mutated Metastatic Castration-Resistant Prostate Cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2024, 42, 605–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, N.; A Azad, A.; Carles, J.; Fay, A.P.; Matsubara, N.; Heinrich, D.; Szczylik, C.; De Giorgi, U.; Joung, J.Y.; Fong, P.C.C.; et al. Talazoparib plus enzalutamide in men with first-line metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer (TALAPRO-2): A randomised, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet 2023, 402, 291–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mateo, J.; Carreira, S.; Sandhu, S.; Miranda, S.; Mossop, H.; Perez-Lopez, R.; Nava Rodrigues, D.; Robinson, D.; Omlin, A.; Tunariu, N.; et al. DNA-Repair Defects and Olaparib in Metastatic Prostate Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2015, 373, 1697–1708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro, E.; Romero-Laorden, N.; del Pozo, A.; Lozano, R.; Medina, A.; Puente, J.; Piulats, J.M.; Lorente, D.; Saez, M.I.; Morales-Barrera, R.; et al. PROREPAIR-B: A Prospective Cohort Study of the Impact of Germline DNA Repair Mutations on the Outcomes of Patients With Metastatic Castration-Resistant Prostate Cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2019, 37, 490–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powles, T.; Albiges, L.; Bex, A.; Comperat, E.; Grünwald, V.; Kanesvaran, R.; Kitamura, H.; McKay, R.; Porta, C.; Procopio, G.; et al. Renal cell carcinoma: ESMO Clinical Practice Guideline for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann. Oncol. 2024, 35, 692–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, M.; Jackson-Spence, F.; Beltran, L.; Day, E.; Suarez, C.; Bex, A.; Powles, T.; Szabados, B. Renal cell carcinoma. Lancet 2024, 404, 476–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Northrup, H.; Aronow, M.E.; Bebin, E.M.; Bissler, J.; Darling, T.N.; de Vries, P.J.; Frost, M.D.; Fuchs, Z.; Gosnell, E.S.; Gupta, N.; et al. Updated International Tuberous Sclerosis Complex Diagnostic Criteria and Surveillance and Management Recommendations. Pediatr. Neurol. 2021, 123, 50–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN). NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology: Kidney Cancer; Version 2. 2025. Available online: https://www.nccn.org (accessed on 2 December 2025).

- Bratslavsky, G.; Mendhiratta, N.; Daneshvar, M.; Brugarolas, J.; Ball, M.W.; Metwalli, A.; Nathanson, K.L.; Pierorazio, P.M.; Boris, R.S.; Singer, E.A.; et al. Genetic risk assessment for hereditary renal cell carcinoma: Clinical consensus statement. Cancer 2021, 127, 3957–3966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Motzer, R.J.; Jonasch, E.; Agarwal, N.; Alva, A.; Bagshaw, H.; Baine, M.; Beckermann, K.; Carlo, M.I.; Choueiri, T.K.; Costello, B.A.; et al. NCCN Guidelines® Insights: Kidney Cancer, Version 2.2024. J. Natl. Compr. Cancer Netw. 2024, 22, 4–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Henske, E.P.; Cornejo, K.M.; Wu, C.-L. Renal Cell Carcinoma in Tuberous Sclerosis Complex. Genes 2021, 12, 1585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binderup, M.L.M.; Smerdel, M.; Borgwadt, L.; Nielsen, S.S.B.; Madsen, M.G.; Møller, H.U.; Kiilgaard, J.F.; Friis-Hansen, L.; Harbud, V.; Cortnum, S.; et al. von Hippel-Lindau disease: Updated guideline for diagnosis and surveillance. Eur. J. Med. Genet. 2022, 65, 104538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, Y.; Kong, W.; Cao, M.; Wang, J.; Wang, Z.; Zheng, L.; Wu, X.; Cheng, R.; He, W.; Yang, B.; et al. Genomic Profiling and Response to Immune Checkpoint Inhibition plus Tyrosine Kinase Inhibition in FH-Deficient Renal Cell Carcinoma. Eur. Urol. 2022, 83, 163–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forde, C.; Lim, D.H.; Alwan, Y.; Burghel, G.; Butland, L.; Cleaver, R.; Dixit, A.; Evans, D.G.; Hanson, H.; Lalloo, F.; et al. Hereditary Leiomyomatosis and Renal Cell Cancer: Clinical, Molecular, and Screening Features in a Cohort of 185 Affected Individuals. Eur. Urol. Oncol. 2020, 3, 764–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, L.S.; Linehan, W.M. Molecular genetics and clinical features of Birt–Hogg–Dubé syndrome. Nat. Rev. Urol. 2015, 12, 558–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lalloo, F.; Kulkarni, A.; Chau, C.; Nielsen, M.; Sheaff, M.; Steele, J.; van Doorn, R.; Wadt, K.; Hamill, M.; Torr, B.; et al. Clinical practice guidelines for the diagnosis and surveillance of BAP1 tumour predisposition syndrome. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 2023, 31, 1261–1269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; Tretiakova, M.S.; Troxell, M.L.; Osunkoya, A.O.; Fadare, O.; Sangoi, A.R.; Shen, S.S.; Lopez-Beltran, A.; Mehra, R.; Heider, A.; et al. Tuberous sclerosis-associated renal cell carcinoma: A clinicopathologic study of 57 separate carcinomas in 18 patients. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 2014, 38, 1457–1467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daniels, A.B.; Tirosh, A.; Huntoon, K.; Mehta, G.U.; Spiess, P.E.; Friedman, D.L.; Waguespack, S.G.; Kilkelly, J.E.; Rednam, S.; Pruthi, S.; et al. Guidelines for surveillance of patients with von Hippel-Lindau disease: Consensus statement of the International VHL Surveillance Guidelines Consortium and VHL Alliance. Cancer 2023, 129, 2927–2940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krueger, D.A.; Northrup, H.; Northrup, H.; Krueger, D.A.; Roberds, S.; Smith, K.; Sampson, J.; Korf, B.; Kwiatkowski, D.J.; Mowat, D.; et al. Tuberous Sclerosis Complex Surveillance and Management: Recommendations of the 2012 International Tuberous Sclerosis Complex Consensus Conference. Pediatr. Neurol. 2013, 49, 255–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jonasch, E.; Donskov, F.; Iliopoulos, O.; Rathmell, W.K.; Narayan, V.K.; Maughan, B.L.; Oudard, S.; Else, T.; Maranchie, J.K.; Welsh, S.J.; et al. Belzutifan for Renal Cell Carcinoma in von Hippel–Lindau Disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 2021, 385, 2036–2046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pezzicoli, G.; Ciciriello, F.; Musci, V.; Salonne, F.; Ragno, A.; Rizzo, M. Genomic Profiling and Molecular Characterization of Clear Cell Renal Cell Carcinoma. Curr. Oncol. 2023, 30, 9276–9290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choueiri, T.K.; Heng, D.Y.C.; Lee, J.L.; Cancel, M.; Verheijen, R.B.; Mellemgaard, A.; Ottesen, L.H.; Frigault, M.M.; L’hErnault, A.; Szijgyarto, Z.; et al. Efficacy of Savolitinib vs Sunitinib in Patients With MET-Driven Papillary Renal Cell Carcinoma. JAMA Oncol. 2020, 6, 1247–1255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, Y.; Keam, B.; Kim, M.; Yoon, S.; Kim, D.; Choi, J.G.; Seo, J.Y.; Park, I.; Lee, J.L. Bevacizumab Plus Erlotinib Combination Therapy for Advanced Hereditary Leiomyomatosis and Renal Cell Carcinoma-Associated Renal Cell Carcinoma: A Multicenter Retrospective Analysis in Korean Patients. Cancer Res. Treat. 2019, 51, 1549–1556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN). NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology: Genet-ic/Familial High-Risk Assessment: Colorectal, Endometrial, and Gastric; Version 1.2025, Updated 13 June 2025. Available online: https://www.nccn.org (accessed on 2 December 2025).

- Pivovarcikova, K.; Pitra, T.; Alaghehbandan, R.; Buchova, K.; Steiner, P.; Hajkova, V.; Ptakova, N.; Subrt, I.; Skopal, J.; Svajdler, P.; et al. Lynch syndrome-associated upper tract urothelial carcinoma frequently occurs in patients older than 60 years: An opportunity to revisit urology clinical guidelines. Virchows Arch. 2023, 483, 517–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Somoto, T.; Utsumi, T.; Ikeda, R.; Ishitsuka, N.; Noro, T.; Suzuki, Y.; Iijima, S.; Sugizaki, Y.; Oka, R.; Endo, T.; et al. Navigating Therapeutic Landscapes in Urothelial Cancer: From Chemotherapy to Pre-cision Immuno-Oncology. Cancers 2025, 17, 3367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masson-Lecomte, A.; Birtle, A.; Pradere, B.; Capoun, O.; Compérat, E.; Domínguez-Escrig, J.L.; Liedberg, F.; Makaroff, L.; Mariappan, P.; Moschini, M.; et al. European Association of Urology Guidelines on Upper Urinary Tract Urothelial Carcinoma: Summary of the 2025 Update. Eur. Urol. 2025, 87, 697–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seppälä, T.T.; Latchford, A.; Negoi, I.; Soares, A.S.; Jimenez-Rodriguez, R.; Sánchez-Guillén, L.; Evans, D.G.; Ryan, N.; Crosbie, E.J.; Dominguez-Valentin, M.; et al. European guidelines from the EHTG and ESCP for Lynch syndrome: An updated third edition of the Mallorca guidelines based on gene and gender. BJS 2020, 108, 484–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindner, A.K.; Schachtner, G.; Tulchiner, G.; Thurnher, M.; Untergasser, G.; Obrist, P.; Pipp, I.; Steinkohl, F.; Horninger, W.; Culig, Z.; et al. Lynch Syndrome: Its Impact on Urothelial Carcinoma. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Z.; Song, F.; Zhong, J. Urinary Biomarkers in Bladder Cancer: FDA-Approved Tests and Emerging Tools for Diagnosis and Surveillance. Cancers 2025, 17, 3425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiorentino, V.; Pizzimenti, C.; Franchina, M.; Rossi, E.D.; Tralongo, P.; Carlino, A.; Larocca, L.M.; Martini, M.; Fadda, G.; Pierconti, F. Bladder Epicheck Test: A Novel Tool to Support Urothelial Carcinoma Diagnosis in Urine Samples. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 12489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jaszek, N.; Bogdanowicz, A.; Siwiec, J.; Starownik, R.; Kwaśniewski, W.; Mlak, R. Epigenetic Biomarkers as a New Diagnostic Tool in Bladder Cancer—From Early Detection to Prognosis. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 7159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Der Post, R.S.; Kiemeney, L.A.; Ligtenberg, M.J.L.; Witjes, J.A.; De Kaa, C.A.H.-V.; Bodmer, D.; Schaap, L.; Kets, C.M.; Van Krieken, J.H.J.M.; Hoogerbrugge, N. Risk of urothelial bladder cancer in Lynch syndrome is increased, in particular among MSH2 mutation carriers. J. Med. Genet. 2010, 47, 464–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rouprêt, M.; Seisen, T.; Birtle, A.J.; Capoun, O.; Compérat, E.M.; Dominguez-Escrig, J.L.; Andersson, I.G.; Liedberg, F.; Mariappan, P.; Mostafid, A.H.; et al. European Association of Urology Guidelines on Upper Urinary Tract Urothelial Carcinoma: 2023 Update. Eur. Urol. 2023, 84, 49–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lonati, C.; Necchi, A.; Rivas, J.G.; Afferi, L.; Laukhtina, E.; Martini, A.; Ventimiglia, E.; Colombo, R.; Gandaglia, G.; Salonia, A.; et al. Upper Tract Urothelial Carcinoma in the Lynch Syndrome Tumour Spectrum: A Comprehensive Overview from the European Association of Urology-Young Academic Urologists and the Global Society of Rare Genitourinary Tumors. Eur. Urol. Oncol. 2022, 5, 30–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wakai, K.; Utsumi, T.; Yoneda, K.; Oka, R.; Endo, T.; Yano, M.; Fujimura, M.; Kamiya, N.; Sekita, N.; Mikami, K.; et al. Development and external validation of a nomogram to predict high-grade papillary bladder cancer before first-time transurethral resection of the bladder tumor. Int. J. Clin. Oncol. 2018, 23, 957–964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Utsumi, T.; Iijima, S.; Sugizaki, Y.; Mori, T.; Somoto, T.; Kato, S.; Oka, R.; Endo, T.; Kamiya, N.; Suzuki, H. Laparoscopic adrenalectomy for adrenal tumors with endocrine activity: Perioperative management pathways for reduced complications and improved outcomes. Int. J. Urol. 2023, 30, 818–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neumann, H.P.H.; Tsoy, U.; Bancos, I.; Amodru, V.; Walz, M.K.; Tirosh, A.; Kaur, R.J.; McKenzie, T.; Qi, X.; Bandgar, T.; et al. Comparison of Pheochromocytoma-Specific Morbidity and Mortality Among Adults With Bilateral Pheochromocytomas Undergoing Total Adrenalectomy vs Cortical-Sparing Adrenalectomy. JAMA Netw. Open 2019, 2, e198898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nölting, S.; Bechmann, N.; Taieb, D.; Beuschlein, F.; Fassnacht, M.; Kroiss, M.; Eisenhofer, G.; Grossman, A.; Pacak, K. Personalized Management of Pheochromocytoma and Paraganglioma. Endocr. Rev. 2021, 43, 199–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenders, J.W.M.; Duh, Q.-Y.; Eisenhofer, G.; Gimenez-Roqueplo, A.-P.; Grebe, S.K.G.; Murad, M.H.; Naruse, M.; Pacak, K.; Young, W.F., Jr. Pheochromocytoma and Paraganglioma: An Endocrine Society Clinical Practice Guideline. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2014, 99, 1915–1942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taïeb, D.; Nölting, S.; Perrier, N.D.; Fassnacht, M.; Carrasquillo, J.A.; Grossman, A.B.; Clifton-Bligh, R.; Wanna, G.B.; Schwam, Z.G.; Amar, L.; et al. Management of phaeochromocytoma and paraganglioma in patients with germline SDHB pathogenic variants: An international expert Consensus statement. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2023, 20, 168–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sukrithan, V.; Perez, K.; Pandit-Taskar, N.; Jimenez, C. Management of metastatic pheochromocytomas and paragangliomas: When and what. Curr. Probl. Cancer 2024, 51, 101116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkaissi, H.; Nazari, M.A.; Vanova, K.H.; Uher, O.; Gordon, C.M.; Talvacchio, S.; Diachenko, N.; Mukvich, O.; Wang, H.; Glod, J.; et al. Rapid Cardiovascular Response to Belzutifan in HIF2A-Mediated Paraganglioma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2024, 391, 1552–1555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fassnacht, M.; Dekkers, O.M.; Else, T.; Baudin, E.; Berruti, A.; de Krijger, R.R.; Haak, H.R.; Mihai, R.; Assie, G.; Terzolo, M. European Society of Endocrinology Clinical Practice Guidelines on the management of adrenocortical carcinoma in adults, in collaboration with the European Network for the Study of Adrenal Tumors. Eur. J. Endocrinol. 2018, 179, G1–G46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Genturis, T.E.R.N.; Frebourg, T.; Lagercrantz, S.B.; Oliveira, C.; Magenheim, R.; Evans, D.G. Guidelines for the Li–Fraumeni and heritable TP53-related cancer syndromes. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 2020, 28, 1379–1386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyts, E.R.-D.; A McGlynn, K.; Okamoto, K.; Jewett, M.A.S.; Bokemeyer, C. Testicular germ cell tumours. Lancet 2016, 387, 1762–1774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, L.A.; Pankratz, N.; Lane, J.; Krailo, M.; Roesler, M.; Richardson, M.; Frazier, A.L.; Amatruda, J.F.; Poynter, J.N. Klinefelter syndrome in males with germ cell tumors: A report from the Children’s Oncology Group. Cancer 2018, 124, 3900–3908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robson, M.E.; Bradbury, A.R.; Arun, B.; Domchek, S.M.; Ford, J.M.; Hampel, H.L.; Lipkin, S.M.; Syngal, S.; Wollins, D.S.; Lindor, N.M. American Society of Clinical Oncology Policy Statement Update: Genetic and Genomic Testing for Cancer Susceptibility. J. Clin. Oncol. 2015, 33, 3660–3667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richards, S.; Aziz, N.; Bale, S.; Bick, D.; Das, S.; Gastier-Foster, J.; Grody, W.W.; Hegde, M.; Lyon, E.; Spector, E.; et al. Standards and guidelines for the interpretation of sequence variants: A joint consensus recommendation of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics and the Association for Molecular Pathology. Genet. Med. 2015, 17, 405–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uhlmann, W.R.; McKeon, A.J.; Wang, C. Genetic counseling, virtual visits, and equity in the era of COVID-19 and beyond. J. Genet. Couns. 2021, 30, 1038–1045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghoreyshi, N.; Heidari, R.; Farhadi, A.; Chamanara, M.; Farahani, N.; Vahidi, M.; Behroozi, J. Next-generation sequencing in cancer diagnosis and treatment: Clinical applications and future directions. Discov. Oncol. 2025, 16, 578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durães, C.; Gomes, C.P.; Costa, J.L.; Quagliata, L. Demystifying the Discussion of Sequencing Panel Size in Oncology Genetic Testing. Eur. Med. J. 2022, 7, 68–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagger, F.O.; Borgwardt, L.; Jespersen, A.S.; Hansen, A.R.; Bertelsen, B.; Kodama, M.; Nielsen, F.C. Whole genome sequencing in clinical practice. BMC Med. Genom. 2024, 17, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nurchis, M.C.; Radio, F.C.; Salmasi, L.; Alizadeh, A.H.; Raspolini, G.M.; Altamura, G.; Tartaglia, M.; Dallapiccola, B.; Pizzo, E.; Gianino, M.M.; et al. Cost-Effectiveness of Whole-Genome vs Whole-Exome Sequencing Among Children With Suspected Genetic Disorders. JAMA Netw. Open 2024, 7, e2353514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stuppia, L.; Antonucci, I.; Palka, G.; Gatta, V. Use of the MLPA Assay in the Molecular Diagnosis of Gene Copy Number Alterations in Human Genetic Diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2012, 13, 3245–3276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerkhof, J.; Schenkel, L.C.; Reilly, J.; McRobbie, S.; Aref-Eshghi, E.; Stuart, A.; Rupar, C.A.; Adams, P.; Hegele, R.A.; Lin, H.; et al. Clinical Validation of Copy Number Variant Detection from Targeted Next-Generation Sequencing Panels. J. Mol. Diagn. 2017, 19, 905–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agiannitopoulos, K.; Pepe, G.; Tsaousis, G.N.; Potska, K.; Bouzarelou, D.; Katseli, A.; Ntogka, C.; Meintani, A.; Tsoulos, N.; Giassas, S.; et al. Copy Number Variations (CNVs) Account for 10.8% of Pathogenic Variants in Patients Referred for Hereditary Cancer Testing. Cancer Genom.-Proteom. 2023, 20, 448–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hemminki, K.; Kiemeney, L.A.; Morgans, A.K.; Ranniko, A.; Pichler, R.; Hemminki, O.; Culig, Z.; Mulders, P.; Bangma, C.H. Hereditary and Familial Traits in Urological Cancers and Their Underlying Genes. Eur. Urol. Open Sci. 2024, 69, 13–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Russo, J.; Giri, V.N. Germline testing and genetic counselling in prostate cancer. Nat. Rev. Urol. 2022, 19, 331–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loeb, S.; Vadaparampil, S.T.; Giri, V.N. Germline testing for prostate cancer: Current state and opportunities for enhanced access. EBioMedicine 2025, 116, 105705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leung, E.Y.L.; Robbins, H.L.; Zaman, S.; Lal, N.; Morton, D.; Dew, L.; Williams, A.P.; Wallis, Y.; Bell, J.; Raghavan, M.; et al. The potential clinical utility of Whole Genome Sequencing for patients with cancer: Evaluation of a regional implementation of the 100,000 Genomes Project. Br. J. Cancer 2024, 131, 1805–1813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witt, D.; Sturm, M.; Stäbler, A.; Menden, B.; Ruisinger, L.; Bosse, K.; Gruber, I.; Hartkopf, A.; Gauß, S.; Demidov, G.; et al. Clinical genome sequencing in patients with hereditary breast and ovarian cancer: Concept, implementation and benefits. Breast 2025, 82, 104505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szalai, C. Arguments for and against the whole-genome sequencing of newborns. Am. J. Transl. Res. 2023, 15, 6255–6263. [Google Scholar]

- Rahman, B.; Lanceley, A.; Kristeleit, R.S.; A Ledermann, J.; Lockley, M.; McCormack, M.; Mould, T.; Side, L. Mainstreamed genetic testing for women with ovarian cancer: First-year experience. J. Med. Genet. 2018, 56, 195–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bokkers, K.; Vlaming, M.; Engelhardt, E.G.; Zweemer, R.P.; van Oort, I.M.; Kiemeney, L.A.L.M.; Bleiker, E.M.A.; Ausems, M.G.E.M. The Feasibility of Implementing Mainstream Germline Genetic Testing in Routine Cancer Care—A Systematic Review. Cancers 2022, 14, 1059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vlaming, M.; Ausems, M.G.E.M.; Kiemeney, L.A.L.M.; Schijven, G.; van Melick, H.H.E.; Noordzij, M.A.; Somford, D.M.; van der Poel, H.G.; Wijburg, C.J.; Wijsman, B.P.; et al. Experience of urologists, oncologists and nurse practitioners with mainstream genetic testing in metastatic prostate cancer. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. 2024, 28, 789–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vrečar, I.; Hristovski, D.; Peterlin, B. Telegenetics: An Update on Availability and Use of Telemedicine in Clinical Genetics Service. J. Med. Syst. 2016, 41, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Husereau, D.; Villalba, E.; Muthu, V.; Mengel, M.; Ivany, C.; Steuten, L.; Spinner, D.S.; Sheffield, B.; Yip, S.; Jacobs, P.; et al. Progress toward Health System Readiness for Genome-Based Testing in Canada. Curr. Oncol. 2023, 30, 5379–5394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Childers, K.K.; Maggard-Gibbons, M.; Macinko, J.; Childers, C.P. National Distribution of Cancer Genetic Testing in the United States: Evidence for a Gender Disparity in Hereditary Breast and Ovarian Cancer. JAMA Oncol. 2018, 4, 876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Clinical Scenario/Syndrome | Key Genes (Typical Panel) | Candidates for Testing | Key Management Implications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Metastatic prostate cancer (any histology) | HRR genes (BRCA2, BRCA1, ATM, CHEK2, PALB2, RAD51D, etc.) | All men with metastatic hormone-sensitive or castration-resistant prostate cancer | Enables PARP inhibitor use and intensified systemic therapy; prompts cascade testing. |

| High-/very-high–risk or node-positive localized prostate cancer; strong family history | HRR genes ± HOXB13 | Men with high-/very-high–risk or node-positive disease; men ≤ 60 years or with multiple affected first-degree relatives | Supports tailored PSA screening and lower biopsy threshold in carriers; informs use or avoidance of conservative active surveillance. |

| Prostate cancer with features suggestive of Lynch syndrome | MMR genes (MLH1, MSH2, MSH6, PMS2, EPCAM) | Men with prostate cancer plus personal or family history suggestive of Lynch syndrome | Confirms need for colonoscopic and UTUC surveillance; may identify candidates for PD-1 blockade in dMMR/MSI-high disease. |

| Unaffected men from high-risk families | Same panel as proband | Adult male first-degree relatives in families with a known pathogenic variant | Enables predictive testing; supports earlier and risk-adapted PSA-based screening. |

| Trigger Category | Operational Criterion |

|---|---|

| Age at diagnosis | RCC < 46 years |

| Tumor number/laterality | Bilateral and/or multifocal RCC |

| Family history | ≥1 first- or second-degree relative with RCC |

| Histology suggestive of a syndrome | Non-clear-cell or hybrid oncocytic patterns |

| Syndromic/extra-renal features | Findings typical of a hereditary syndrome |

| Tumor pathology/genomics | IHC or sequencing indicating a germline pathway |

| Clinician judgment | Early onset with atypical features or multiple triggers |

| Syndrome (Gene) | Renal Imaging | Extra-Renal Screening | Intervention Threshold | Special Cautions |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| VHL (VHL) | Abdominal MRI every 12 months | Ophthalmology Brain/spine MRI Plasma/urine metanephrines | 3 cm (nephron-sparing) | Multidisciplinary protocol |

| HLRCC (FH) | Kidney MRI every 12 months from early adolescence (some start at 8–10 years) | Gynecology (uterine); Dermatology (cutaneous) | Early surgery, even <3 cm | Low threshold; rapid referral |

| HPRC (MET) | Kidney MRI every 12–24 months from ~age 30 (shorten if growth) Ultrasound not preferred | — | 3 cm (nephron-sparing) | Anticipate staged procedures |

| BHD (FLCN) | Kidney MRI every 1–2 years from ~age 20 Ultrasound if MRI unavailable | Baseline chest CT Pneumothorax risk education | 3 cm → nephron-sparing/ablation | Avoid diving/high-pressure exposure |

| BAP1-TPDS (BAP1) | Kidney MRI every 12 months from ~age 30 (shorten if lesions) Ultrasound if MRI unavailable | Dermatology (skin) Ophthalmology (uveal) Mesothelioma awareness | Lower threshold for intervention on enhancing solid mass; prioritize nephron-sparing | Aggressive biology; asbestos avoidance; coordinate care |

| TSC (TSC1/2) | Kidney MRI every 1–3 years lifelong Annual blood pressure and eGFR | Neurology Dermatology Screen LAM (women) | AML ≥ 3–4 cm or rapid growth → intervene | Hemorrhage risk; coordinate care |

| Context in Lynch Syndrome | Predominant Genes | Target Population | Surveillance Focus |

|---|---|---|---|

| UTUC | Mainly MSH2 (also MLH1, MSH6, PMS2) | Lynch syndrome carriers from ~30–35 years; particularly MSH2 carriers; patients with prior UTUC | Annual urinalysis (±cytology in MSH2 carriers); prompt CT/MR urography for any hematuria; after nephroureterectomy, contralateral upper-tract imaging at least annually for several years. |

| Bladder cancer | Mainly MSH2 | Lynch syndrome carriers, especially older men with MSH2 variants | Urine-based surveillance for UTUC usually detects many bladder tumors; cystoscopy triggered by hematuria, atypical cytology, or imaging findings; once diagnosed, follow standard NMIBC/MIBC guidelines. |

| Lynch syndrome without known UC | MMR genes (MLH1, MSH2, MSH6, PMS2, EPCAM) | All confirmed Lynch syndrome carriers | Counsel regarding UTUC as a sentinel cancer; yearly urinalysis; low threshold to investigate hematuria; coordinate with colorectal and gynecologic surveillance according to Lynch syndrome guidelines. |

| Domain | Clinician Notes (What to Cover) | Patient-Facing Phrasing (Plain Language) |

|---|---|---|

| Purpose & scope | Germline vs. tumor testing, panel, lab, turnaround time, possible extra sample | “This looks for inherited and tumor changes to guide your care and your family’s.” |

| Results & reclassification | P/LP, VUS, negative; lab reclassification policy | “Results may show a risk, be uncertain, or show none. We’ll update you if meanings change.” |

| Family impact (cascade) | Who to offer testing; logistics; letters for relatives | “If an inherited change is found, close relatives can get a simple test.” |

| Privacy, documentation & coverage | Data handling, EHR location, who can access, insurance/costs | “Your results are confidential. We’ll explain storage, access, and coverage.” |

| Pediatrics/minors policy | When to test children; consent/assent; childhood-onset vs. adult-onset | “Children are tested only if it affects care now, unless there’s a strong reason.” |

| After testing—if P/LP | No change for VUS; phenotype-driven care for negative; re-test options | “If uncertain or negative, we follow standard care and watch for updates.” |

| Recontact & support | How/when recontact happens; portal use; psychosocial resources | “We’ll contact you if things change or new options appear; support is available.” |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Somoto, T.; Utsumi, T.; Ikeda, R.; Ishitsuka, N.; Noro, T.; Suzuki, Y.; Iijima, S.; Sugizaki, Y.; Oka, R.; Endo, T.; et al. Precision Care for Hereditary Urologic Cancers: Genetic Testing, Counseling, Surveillance, and Therapeutic Implications. Curr. Oncol. 2025, 32, 698. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol32120698

Somoto T, Utsumi T, Ikeda R, Ishitsuka N, Noro T, Suzuki Y, Iijima S, Sugizaki Y, Oka R, Endo T, et al. Precision Care for Hereditary Urologic Cancers: Genetic Testing, Counseling, Surveillance, and Therapeutic Implications. Current Oncology. 2025; 32(12):698. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol32120698

Chicago/Turabian StyleSomoto, Takatoshi, Takanobu Utsumi, Rino Ikeda, Naoki Ishitsuka, Takahide Noro, Yuta Suzuki, Shota Iijima, Yuka Sugizaki, Ryo Oka, Takumi Endo, and et al. 2025. "Precision Care for Hereditary Urologic Cancers: Genetic Testing, Counseling, Surveillance, and Therapeutic Implications" Current Oncology 32, no. 12: 698. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol32120698

APA StyleSomoto, T., Utsumi, T., Ikeda, R., Ishitsuka, N., Noro, T., Suzuki, Y., Iijima, S., Sugizaki, Y., Oka, R., Endo, T., Kamiya, N., & Suzuki, H. (2025). Precision Care for Hereditary Urologic Cancers: Genetic Testing, Counseling, Surveillance, and Therapeutic Implications. Current Oncology, 32(12), 698. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol32120698