A Goal Without a Plan Is Just a Wish—Creating a Personalized Aftercare Plan for Breast Cancer Patients Supported by the Breast Cancer Aftercare Decision Aid

Abstract

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

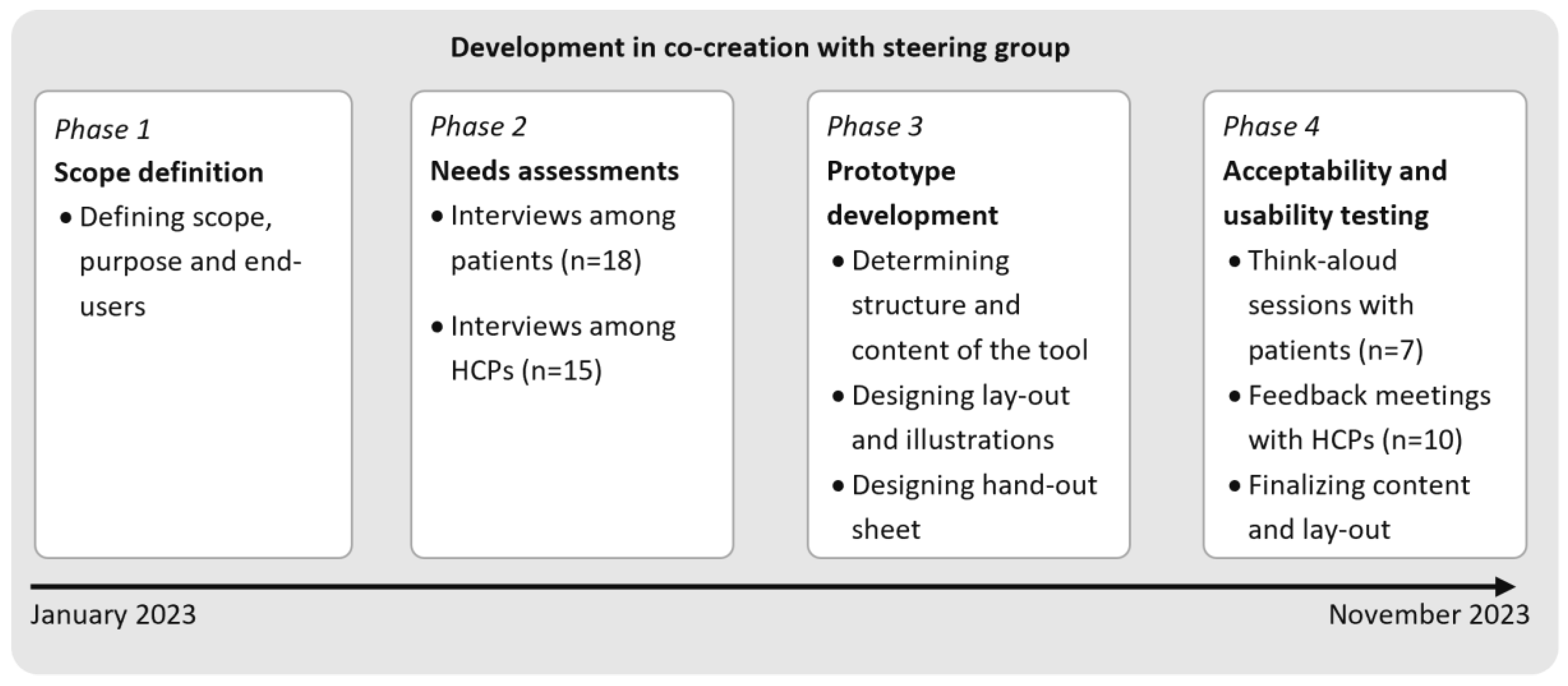

2. Materials and Methods

- Phase 1: Scope definition

- Phase 2: Needs assessments among patients and HCPs

- Phase 3: Prototype development

- Phase 4: Usability and acceptability testing

3. Results

- Phase 1: Scope definition

- Phase 2: Needs assessments among patients and HCPs

- Phase 2.1. Needs and wishes of patients

- Phase 2.2. Needs and wishes of HCPs

- Phase 2.3. Potential barriers and facilitators for implementation of the PtDA

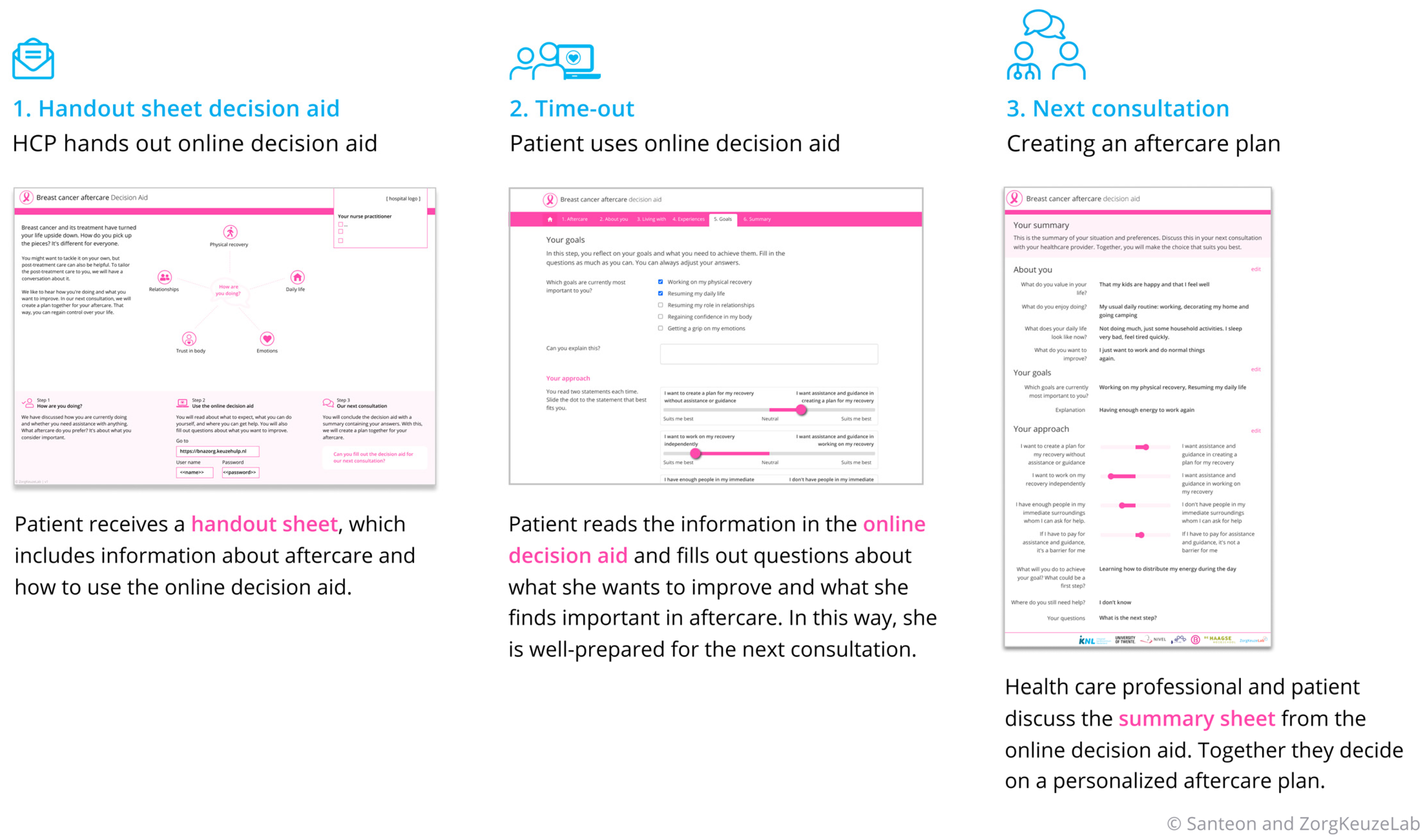

- Phase 3: Prototype development

- Component 1: handout sheet

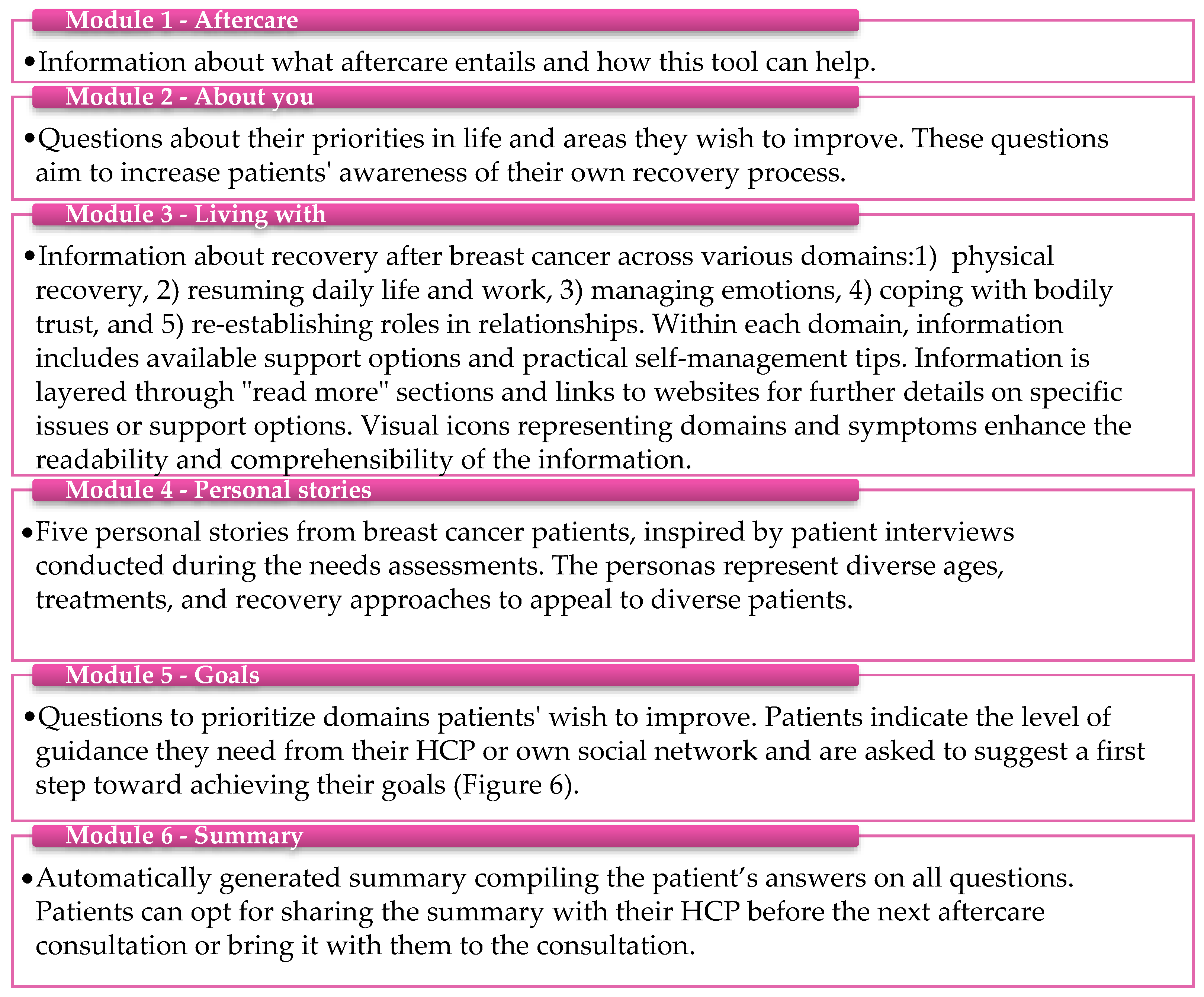

- Component 2: Online tool

- Component 3: The summary sheet

- Phase 4: Acceptability and usability testing

- Phase 4.1. Perceptions of patients

- Phase 4.2. Perceptions of HCPs

4. Discussion

Practical Implications

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| BC-ADA | Breast Cancer Aftercare Decision Aid |

| HCP | Healthcare professional |

| NP | Nurse practitioner |

| NS | Nurse specialist |

| PtDA | Patient decision aid |

| SDM | Shared decision-making |

Appendix A. Interview Scheme for Healthcare Professionals

Part 1: Assessment of care needs

There are also various tools to assess complaints and care needs, such as the Distress Thermometer, mini-PROMs, and the spider web of positive health.

Interviewer explains: In aftercare, patients typically receive various information from healthcare providers, such as common complaints, available care and support in the hospital, assistance outside the hospital, etc.

Interviewer explains: The guidelines recommend using an aftercare plan: an overview containing aftercare information and agreements that the patient can easily keep at hand. At the beginning of aftercare, the patient can collaborate with the healthcare provider to create such a plan. For example, they might decide together what additional support is needed, what ongoing concerns should be addressed, and what follow-up consultations are required.

Interviewer explains: To support the personalization of aftercare, we could develop a tool. This tool could be introduced to the patient by the healthcare provider, after which the patient would use it at home. In the tool, the patient could, for example, read information and answer questions about their care needs. The tool could then generate a summary of the patient’s responses. This summary could be used in the next aftercare conversation to collaboratively develop a personalized aftercare plan with the patient.

|

References

- Rosenberg, J.; Butow, P.N.; Shaw, J.M. The untold story of late effects: A qualitative analysis of breast cancer survivors’ emotional responses to late effects. Support. Care Cancer 2022, 30, 177–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smedsland, S.K.; Falk, R.S.; Reinertsen, K.V.; Kiserud, C.E.; Brekke, M.; Bøhn, S.H.; Dahl, A.A.; Vandraas, K.F. Burden of late effects in a nationwide sample of long-term breast cancer survivors. Cancer 2024, 130, 140–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Springer, F.; Mehnert-Theuerkauf, A.; Gebhardt, C.; Stolzenburg, J.U.; Briest, S. Unmet supportive care needs among cancer patients: Exploring cancer entity-specific needs and associated factors. J. Cancer. Res. Clin. Oncol. 2024, 150, 190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, J.D.; Young, J.M.; Price, M.A.; Butow, P.N.; Solomon, M.J. What are the unmet supportive care needs of people with cancer? A systematic review. Support. Care Cancer 2009, 17, 1117–1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiszer, C.; Dolbeault, S.; Sultan, S.; Brédart, A. Prevalence, intensity, and predictors of the supportive care needs of women diagnosed with breast cancer: A systematic review. Psychooncology 2014, 23, 361–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Ligt, K.M.; de Rooij, B.H.; Walraven, I.; Heins, M.J.; Verloop, J.; Siesling, S.; Korevaar, J.C.; van de Poll-Franse, L.V. Varying severities of symptoms underline the relevance of personalized follow-up care in breast cancer survivors: Latent class cluster analyses in a cross-sectional cohort. Support. Care Cancer 2022, 30, 7873–7883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mayer, D.K.; Nasso, S.F.; Earp, J.A. Defining cancer survivors, their needs, and perspectives on survivorship health care in the USA. Lancet Oncol. 2017, 18, e11–e18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vaz-Luis, I.; Masiero, M.; Cavaletti, G.; Cervantes, A.; Chlebowski, R.T.; Curigliano, G.; Felip, E.; Ferreira, A.R.; Ganz, P.A.; Hegarty, J.; et al. ESMO Expert Consensus Statements on Cancer Survivorship: Promoting high-quality survivorship care and research in Europe. Ann. Oncol. 2022, 33, 1119–1133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kvale, E.A.; Huang, C.H.S.; Meneses, K.M.; Demark-Wahnefried, W.; Bae, S.; Azuero, C.B.; Rocque, G.B.; Bevis, K.S.; Ritchie, C.S. Patient-centered support in the survivorship care transition: Outcomes from the Patient-Owned Survivorship Care Plan Intervention. Cancer 2016, 122, 3232–3242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hua, A.; Sesto, M.E.; Zhang, X.; Wassenaar, T.R.; Tevaarwerk, A.J. Impact of Survivorship Care Plans and Planning on Breast, Colon, and Prostate Cancer Survivors in a Community Oncology Practice. J. Cancer Educ. 2020, 35, 249–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brennan, M.E.; Gormally, J.F.; Butow, P.; Boyle, F.M.; Spillane, A.J. Survivorship care plans in cancer: A systematic review of care plan outcomes. Br. J. Cancer 2014, 111, 1899–1908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van de Poll-Franse, L.V.; Nicolaije, K.A.H.; Ezendam, N.P.M. The impact of cancer survivorship care plans on patient and health care provider outcomes: A current perspective. Acta Oncol. 2017, 56, 134–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, D.K.; Birken, S.A.; Check, D.K.; Chen, R.C. Summing it up: An integrative review of studies of cancer survivorship care plans (2006–2013). Cancer 2015, 121, 978–996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NABON Borstkanker. 2017. Available online: https://richtlijnendatabase.nl/richtlijn/borstkanker/startpagina_-_borstkanker.html (accessed on 18 September 2025).

- van Maaren, M.C.; van Hoeve, J.C.; Korevaar, J.C.; van Hezewijk, M.; Siemerink, E.J.M.; Zeillemaker, A.M.; Klaassen-Dekker, A.; van Uden, D.J.P.; Volders, J.H.; Drossaert, C.H.C.; et al. The effectiveness of personalised surveillance and aftercare in breast cancer follow-up: A systematic review. Support Care Cancer 2024, 32, 323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dekker-Klaassen, A.; Drossaert, C.H.C.; Zeillemaker, A.M.; Wiegersma, J.; Korevaar, J.C.; Siesling, S. Towards Personalized Surveillance and Aftercare After Breast Cancer: Opportunities for Improvements. 2025; in press. [Google Scholar]

- Dekker-Klaassen, A.; Drossaert, C.H.C.; Folkert, L.S.; Van der Lee, M.L.; Guerrero-Paezm, C.; Claassen, S.; Korevaar, J.C.; Siesling, S. Different needs ask for different care: Breast cancer patients’ preferences regarding assessment of care needs and information provision in personalized aftercare. Eur. J. Oncol. Nurs. 2025, 76, 102873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elkefi, S.; Matthews, A.K. Exploring Health Information-Seeking Behavior and Information Source Preferences Among a Diverse Sample of Cancer Survivors: Implications for Patient Education. J. Cancer Educ. 2024, 39, 650–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lubberding, S.; van Uden-Kraan, C.F.; Te Velde, E.A.; Cuijpers, P.; Leemans, C.R.; Verdonck-de Leeuw, I.M. Improving access to supportive cancer care through an eHealth application: A qualitative needs assessment among cancer survivors. J. Clin. Nurs. 2015, 24, 1367–1379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stiggelbout, A.M.; Pieterse, A.H.; De Haes, J.C.J.M. Shared decision making: Concepts, evidence, and practice. Patient Educ. Couns. 2015, 98, 1172–1179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elwyn, G.; Frosch, D.; Thomson, R.; Joseph-Williams, N.; Lloyd, A.; Kinnersley, P.; Cording, E.; Tomson, D.; Dodd, C.; Rollnick, S.; et al. Shared decision making: A model for clinical practice. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2012, 27, 1361–1367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stacey, D.; Légaré, F.; Lewis, K.; Barry, M.J.; Bennett, C.L.; Eden, K.B.; Holmes-Rovner, M.; Llewellyn-Thomas, H.; Lyddiatt, A.; Thomson, R.; et al. Decision aids for people facing health treatment or screening decisions. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2017, CD001431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ke, Y.; Zhou, H.; Chan, R.J.; Chan, A. Decision aids for cancer survivors’ engagement with survivorship care services after primary treatment: A systematic review. J. Cancer Surviv. 2024, 18, 288–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klaassen, L.A.; Dirksen, C.D.; Boersma, L.J.; Hoving, C.; Portz, M.J.G.; Mertens, P.M.G.; Janssen-Engelen, I.L.E.; Lenssen, A.M.M.R.N.; Marais, M.B.; Starren-Goessens, C.M.J.; et al. A novel patient decision aid for aftercare in breast cancer patients: A promising tool to reduce costs by individualizing aftercare. Breast 2018, 41, 144–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ankersmid, J.W.; Siesling, S.; Strobbe, L.J.A.; Bode-meulepas, J.M.; van Riet, Y.E.A.; Engels, N.; Prick, J.C.M.; The, R.; Velting, M.; van Uden-kraan, C.F.; et al. Supporting shared decision making about personalised surveillance after breast cancer: The development of a patient decision aid integrating personalised recurrence risk calculations. JMIR Cancer 2022, 8, e38088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coulter, A.; Stilwell, D.; Kryworuchko, J.; Mullen, P.D.; Ng, C.J.; Van Der Weijden, T. A systematic development process for patient decision aids. BMC Med. Inform. Decis. Mak. 2013, 13, S2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Civilotti, C.; Acquadro Maran, D.; Santagata, F.; Varetto, A.; Stanizzo, M.R. The use of the Distress Thermometer and the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale for screening of anxiety and depression in Italian women newly diagnosed with breast cancer. Support. Care Cancer 2020, 28, 4997–5004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Egdom, L.S.E.; Oemrawsingh, A.; Verweij, L.M.; Lingsma, H.F.; Koppert, L.B.; Verhoef, C.; Klazinga, N.S.; Hazelzet, J.A. Implementing Patient-Reported Outcome Measures in Clinical Breast Cancer Care: A Systematic Review. Value Health 2019, 22, 1197–1226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, S. A Comparative study of Usability Evaluation Methods. Int. J. Comput. Trends Technol. 2015, 22, 103–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klaassen-Dekker, A.; Drossaert, C.H.C.; Van Maaren, M.C.; Van Leeuwen-Stok, A.E.; Retel, V.P.; Korevaar, J.C.; Siesling, S. Personalized surveillance and aftercare for non-metastasized breast cancer: The NABOR study protocol of a multiple interrupted time series design. BMC Cancer 2023, 23, 1112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huber, M.; Jung, H.P.; van den Brekel-Dijkstra, K. Positive Health in practice. In Handbook Positive Health in Primary Care; Bohn Stafleu van Loghum: Houten, The Netherlands, 2022; pp. 133–178. Available online: https://link.springer.com/content/pdf/10.1007/978-90-368-2729-4.pdf (accessed on 30 September 2025).

- Casellas-Grau, A.; Font, A.; Vives, J. Positive psychology interventions in breast cancer. A systematic review. Psychooncology 2014, 23, 9–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coleman, E.A.; Min, S.-J. Home Health Care Services Quarterly Patients’ and Family Caregivers’ Goals for Care During Transitions Out of the Hospital. Home Health Care Serv. Q. 2015, 34, 173–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osborne, R.H.; Batterham, R.W.; Elsworth, G.R.; Hawkins, M.; Buchbinder, R. The grounded psychometric development and initial validation of the Health Literacy Questionnaire (HLQ). BMC Public Health 2013, 13, 658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Discipline | Number |

|---|---|

| Surgical oncologist | 3 |

| Nurse specialist | 4 |

| Nurse practitioner | 1 |

| Radiologist | 2 |

| Psychologist | 1 |

| General practitioner | 2 |

| Patient representative | 2 |

| Researcher | 4 |

| Web developer | 2 |

| According to Patients | N | Example Quote |

|---|---|---|

| Prepares for consultation | 8 | “Before you see her [HCP], that you fill in the tool. For me, that would be easier than having to lay everything out on the table at that moment.” |

| Provides specific information | 7 | “That you can click directly on the topic and know where to look, because searching can take a long time.” |

| Easy access to reliable information | 3 | “You can Google a lot, but you find so much that isn’t true. So, if you have it all in one place where you know it’s reliable information, I would have appreciated that.” |

| Information for family | 2 | “That I can tell my children: ‘Guys, here you can read what this does to me or what I’m struggling with. That way, you might better understand how I feel’” |

| According to HCPs | ||

| Prioritizes patients’ main care needs | 8 | “Self-reflection is naturally more beneficial than if I gave them a symptom checklist to fill out on the spot. So, I can definitely see some value in that preparatory step” |

| Activates patients to engage in their own recovery | 8 | “If the patient has considered for themselves, ‘This is something I would like to work on,’ you have a much higher chance of success than if we recommend something” |

| Information consolidated into one tool | 6 | “It’s especially important to have one place or website where patients can find all information, so that you can easily refer them to a single source” |

| Information normalizes and reassures patients’ experiences | 2 | “That patients read that these things are actually normal and not necessarily a problem that requires intervention. That alone reduces anxiety or stress, and consequently, reduces hospital visits” |

| Information prevents future health problems | 3 | “Education can have a very preventive effect on health problems, even in the future” |

| Aftercare plan facilitates communication with the GP * | 4 | “It’s certainly beneficial if, when they go to a GP, the GP is informed about what has occurred and what is ongoing” |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Dekker-Klaassen, A.; Drossaert, C.H.C.; Thé, R.; Zeillemaker, A.M.; van Hezewijk, M.; De Keulenaar-Suiker, I.M.; Knottnerus, B.J.; Honkoop, A.; van der Lee, M.L.; Korevaar, J.C.; et al. A Goal Without a Plan Is Just a Wish—Creating a Personalized Aftercare Plan for Breast Cancer Patients Supported by the Breast Cancer Aftercare Decision Aid. Curr. Oncol. 2025, 32, 552. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol32100552

Dekker-Klaassen A, Drossaert CHC, Thé R, Zeillemaker AM, van Hezewijk M, De Keulenaar-Suiker IM, Knottnerus BJ, Honkoop A, van der Lee ML, Korevaar JC, et al. A Goal Without a Plan Is Just a Wish—Creating a Personalized Aftercare Plan for Breast Cancer Patients Supported by the Breast Cancer Aftercare Decision Aid. Current Oncology. 2025; 32(10):552. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol32100552

Chicago/Turabian StyleDekker-Klaassen, A., C. H. C. Drossaert, R. Thé, A. M. Zeillemaker, M. van Hezewijk, I. M. De Keulenaar-Suiker, B. J. Knottnerus, A. Honkoop, M. L. van der Lee, J. C. Korevaar, and et al. 2025. "A Goal Without a Plan Is Just a Wish—Creating a Personalized Aftercare Plan for Breast Cancer Patients Supported by the Breast Cancer Aftercare Decision Aid" Current Oncology 32, no. 10: 552. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol32100552

APA StyleDekker-Klaassen, A., Drossaert, C. H. C., Thé, R., Zeillemaker, A. M., van Hezewijk, M., De Keulenaar-Suiker, I. M., Knottnerus, B. J., Honkoop, A., van der Lee, M. L., Korevaar, J. C., Siesling, S., & on behalf of the NABOR Project Group. (2025). A Goal Without a Plan Is Just a Wish—Creating a Personalized Aftercare Plan for Breast Cancer Patients Supported by the Breast Cancer Aftercare Decision Aid. Current Oncology, 32(10), 552. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol32100552