Listening in: Identifying Considerations for Integrating Complementary Therapy into Oncology Care Across Patient, Clinic, and System Levels—A Case Example of a Digital Meditation Tool

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Recruitment and Study Design

2.2. Survey Measures

2.3. Experience with Meditation

2.4. Sample Size

2.5. Data Analysis

3. Results

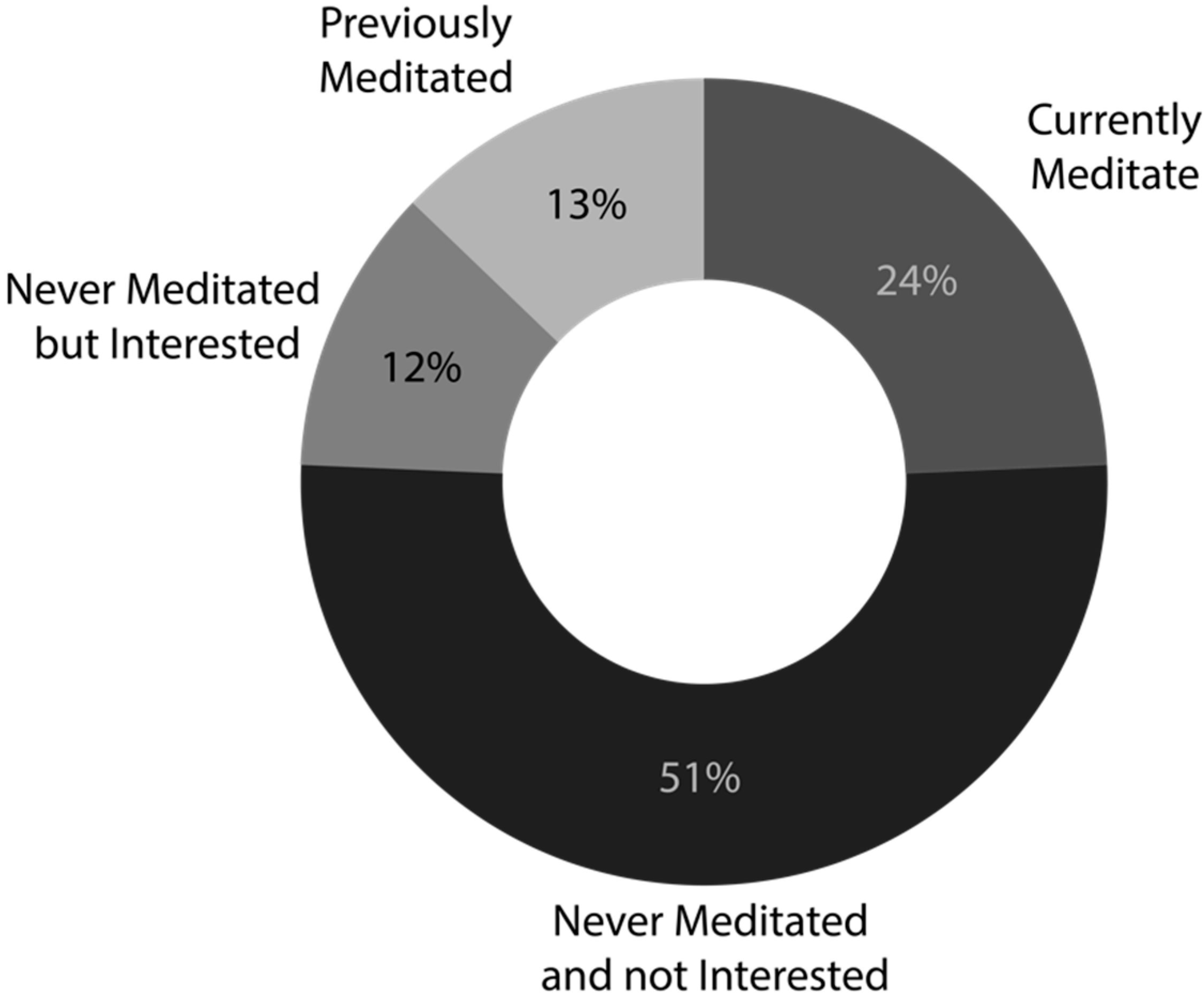

3.1. Experience and Interest in Meditation

3.2. Predictors of Interest in Meditation and a DMT

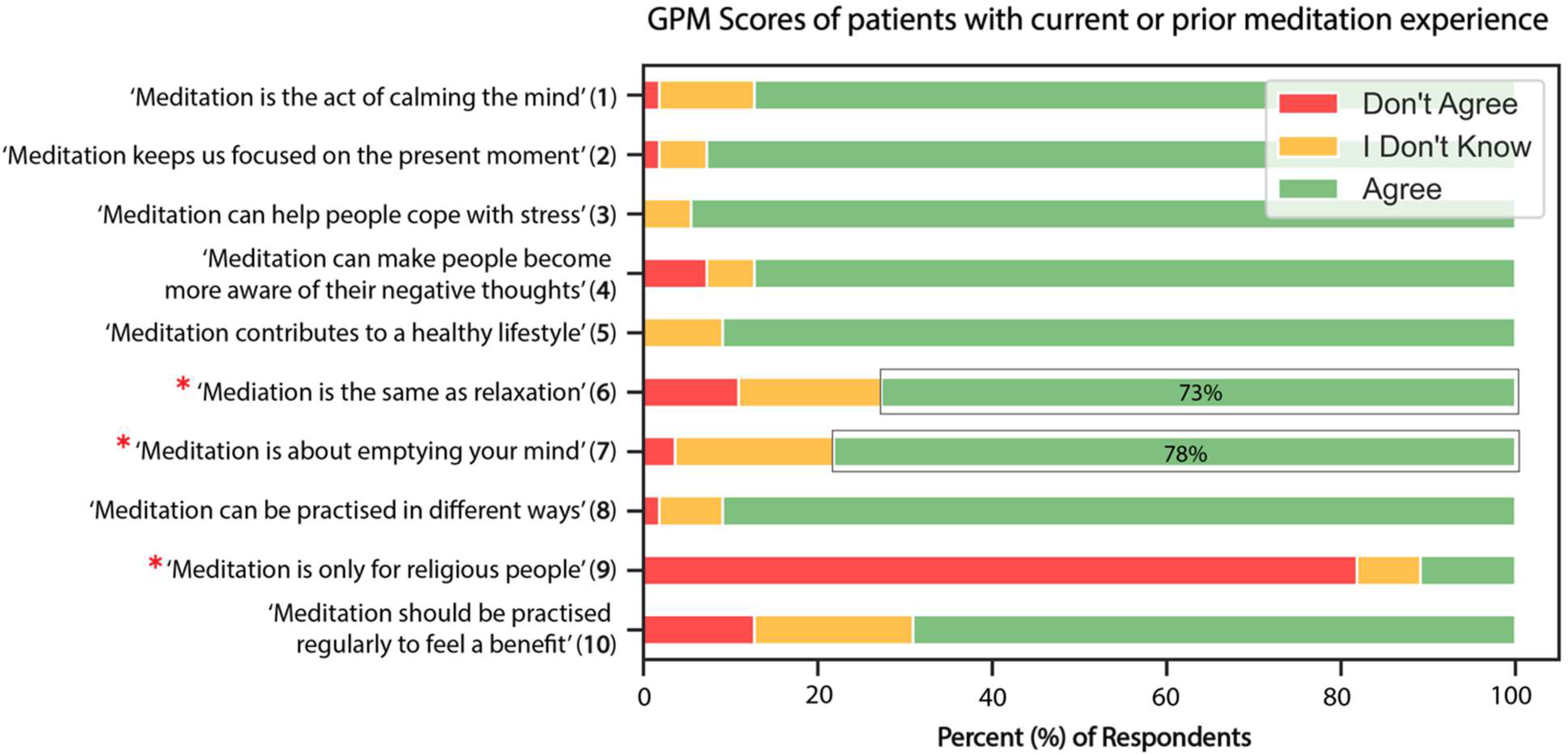

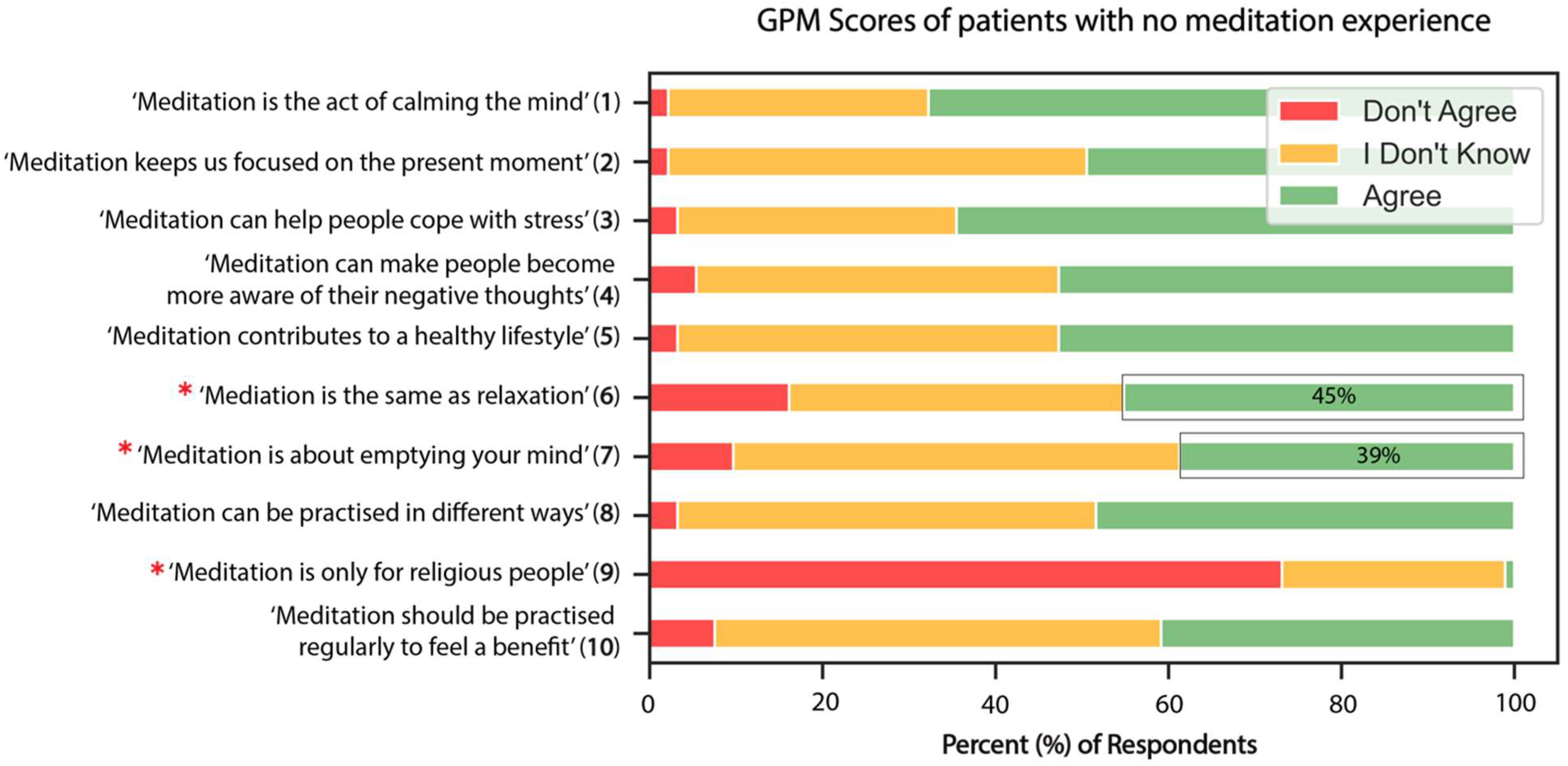

3.3. General Knowledge and Perceptions of Meditation

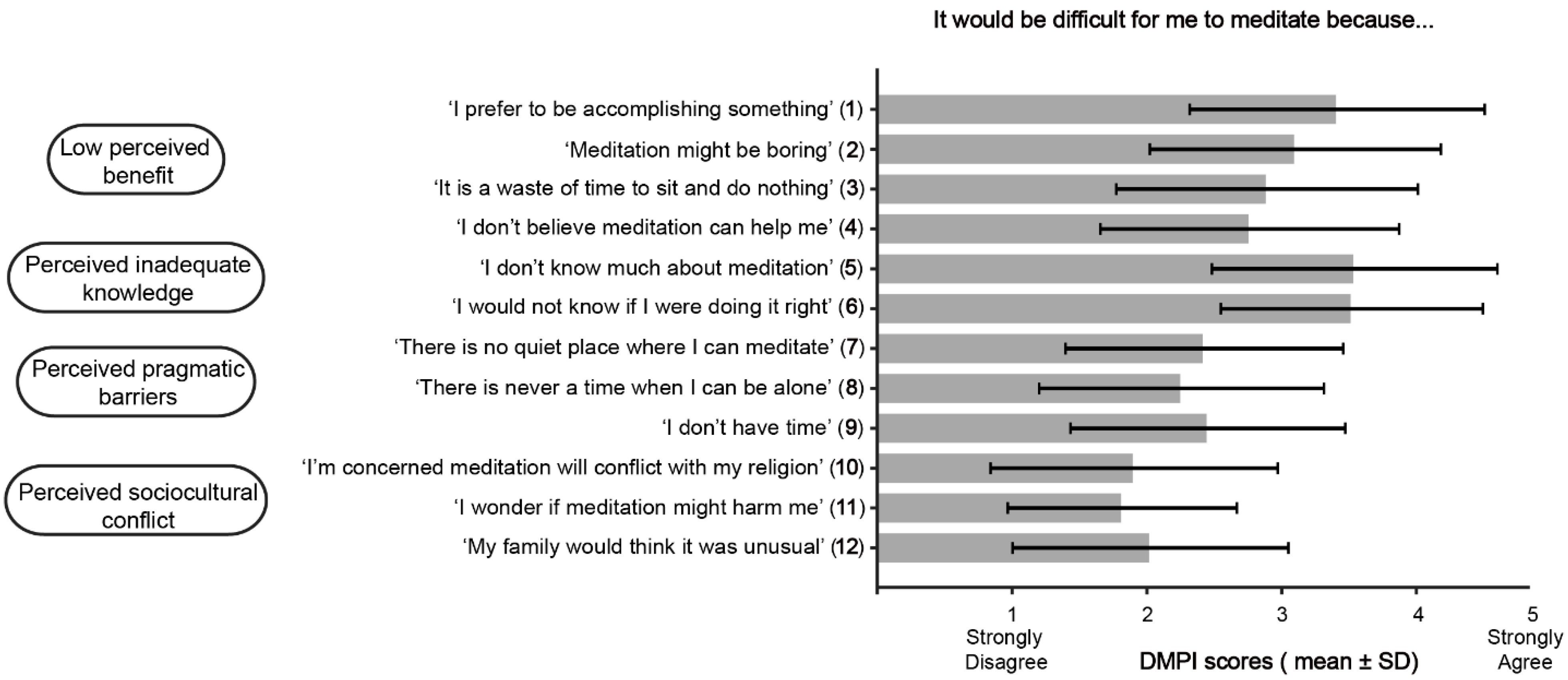

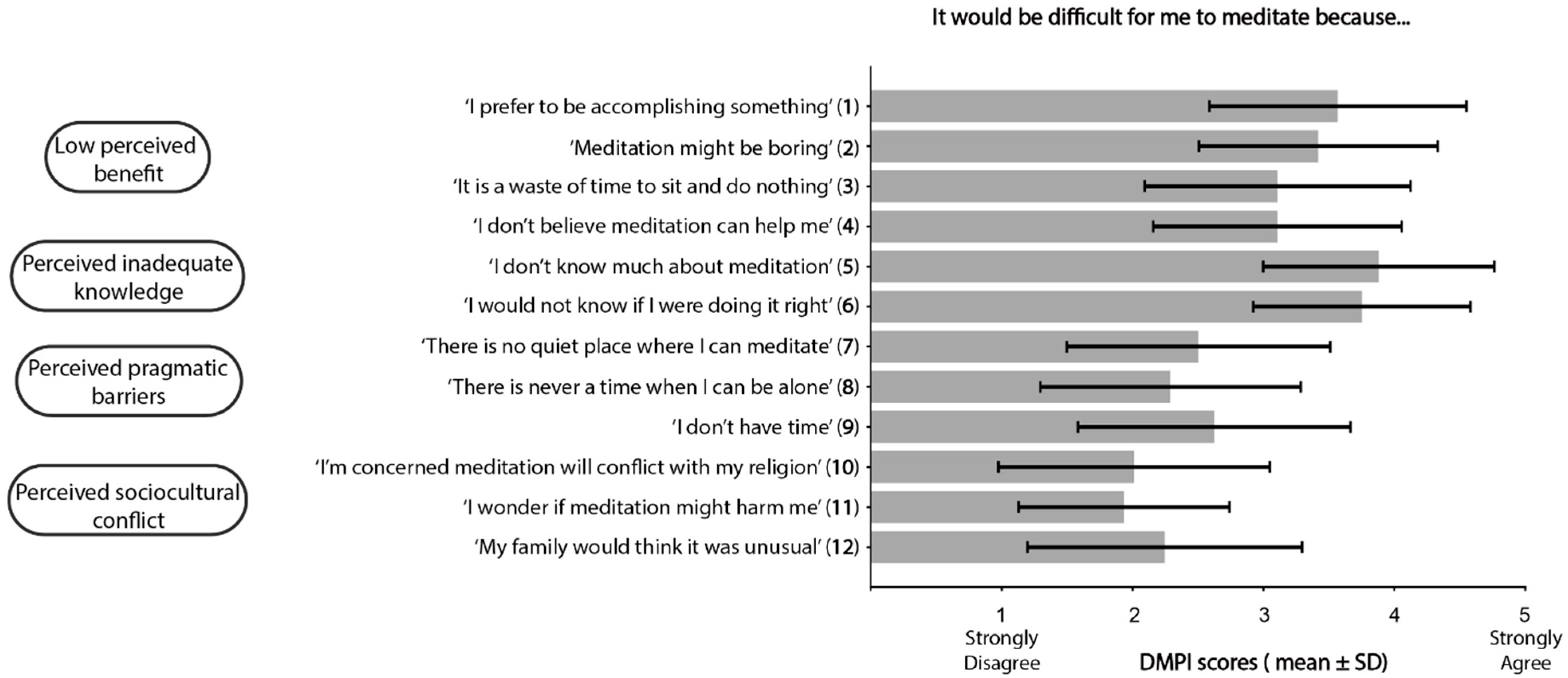

3.4. Barriers to Meditation

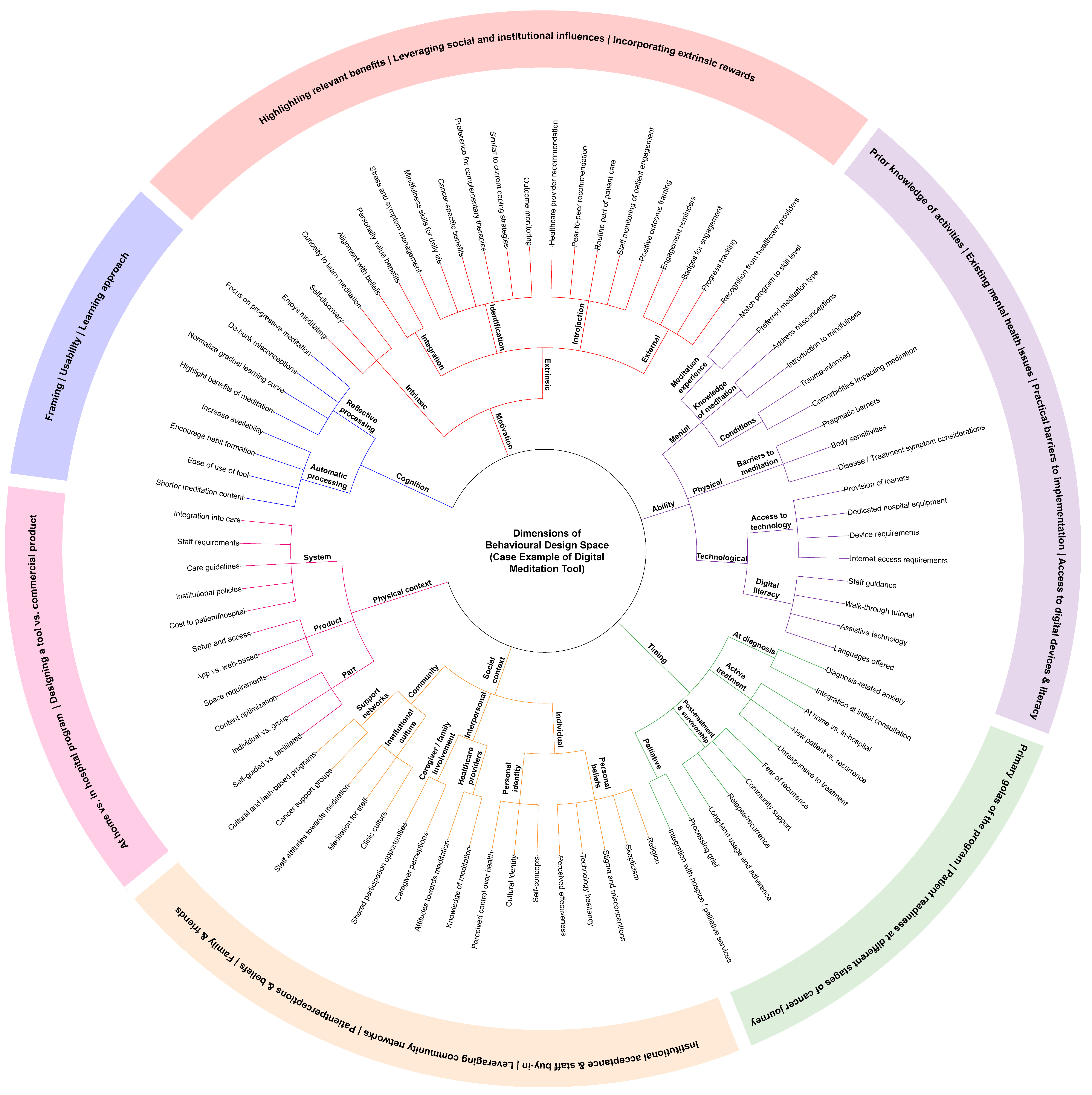

4. Discussion

4.1. Cognition

4.2. Motivation

4.3. Ability

4.4. Timing

4.5. Physical Context

4.6. Social Context

4.7. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Boele, F.; Harley, C.; Pini, S.; Kenyon, L.; Daffu-O’REilly, A.; Velikova, G. Cancer as a chronic illness: Support needs and experiences. BMJ Support. Palliat. Care 2019, 14, e710–e718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miller, K.D.; Nogueira, L.; Devasia, T.; Mariotto, A.B.; Yabroff, K.R.; Jemal, A.; Kramer, J.; Siegel, R.L. Cancer treatment and survivorship statistics, 2022. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2022, 72, 409–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buiting, H.M.; Botman, F.; van der Velden, L.-A.; Brom, L.; van Heest, F.; Bolt, E.E.; de Mol, P.; Bakker, T. Clinicians’ experiences with cancer patients living longer with incurable cancer: A focus group study in the Netherlands. Prim. Health Care Res. Dev. 2023, 24, e29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kvaale, K.; Lian, O.S.; Bondevik, H. ‘Beyond my control’: Dealing with the existential uncertainty of cancer in online texts. Illn. Crisis Loss 2024, 32, 192–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrington, C.B.; Hansen, J.A.; Moskowitz, M.; Todd, B.L.; Feuerstein, M. It’s not over when it’s over: Long-term symptoms in cancer survivors—A systematic review. Int. J. Psychiatry Med. 2010, 40, 163–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niedzwiedz, C.L.; Knifton, L.; Robb, K.A.; Katikireddi, S.V.; Smith, D.J. Depression and anxiety among people living with and beyond cancer: A growing clinical and research priority. BMC Cancer 2019, 19, 943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kirsch, J.L.; Roche, A.I.; Bronars, C.; Donovan, K.A.; Hassett, L.C.; Ehlers, S.L. Emotional distress and future healthcare utilization in oncology populations: A systematic review. Psycho-Oncology 2024, 33, e6322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabat-Zinn, J. Mindfulness-based interventions in context: Past, present, and future. Clin. Psychol. Sci. Pract. 2003, 10, 144–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matis, J.; Svetlak, M.; Slezackova, A.; Svoboda, M.; Šumec, R. Mindfulness-Based Programs for Patients With Cancer via eHealth and Mobile Health: Systematic Review and Synthesis of Quantitative Research. J. Med. Internet Res. 2020, 22, e20709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Lee, E.K.P.; Mak, E.C.W.; Ho, C.Y.; Wong, S.Y.S. Mindfulness-based interventions: An overall review. Br. Med. Bull. 2021, 138, 41–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huebner, J.; Prott, F.J.; Micke, O.; Muecke, R.; Senf, B.; Dennert, G.; Muenstedt, K.; on behalf of PRIO (Working Group Prevention and Integrative Oncology-German Cancer Society). Online Survey of Cancer Patients on Complementary and Alternative Medicine. Oncol. Res. Treat. 2014, 37, 304–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fung, J.; Lim, H.; Vongsirimas, N.; Klainin-Yobas, P. Effectiveness of eHealth mindfulness-based interventions on cancer-related symptoms among cancer patients and survivors: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Telemed. Telecare 2024, 30, 451–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godinho, A.; Dalmia, S.; Phadke, S.; Lalani, Y.; Wach, A.C.; Rana, P.; Wegier, P. Being Mindful of Our Ps and Qs: A Systematic-Narrative Review of the Parallels and Quality of Digital Mindfulness-Based Programs for Cancer Patients. Mindfulness 2025, 16, 2395–2417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, D.; Edwards, E.; Murray, P.; Langevin, H. Implementation Science Methodologies for Complementary and Integrative Health Research. J. Altern. Complement. Med. 2021, 27, S7–S13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damschroder, L.J.; Aron, D.C.; Keith, R.E.; Kirsh, S.R.; Alexander, J.A.; Lowery, J.C. Fostering implementation of health services research findings into practice: A consolidated framework for advancing implementation science. Implement. Sci. 2009, 4, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Michie, S.; van Stralen, M.M.; West, R. The behaviour change wheel: A new method for characterising and designing behaviour change interventions. Implement. Sci. 2011, 6, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wong, E.L.Y.; Nilsen, P.; Chung, V.C.H.; Tian, Y.; Yeoh, E.K. A scoping review of implementation science theories, models, and frameworks—An appraisal of purpose, characteristics, usability, applicability, and testability. Implement. Sci. 2023, 18, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, C.K.B.B.; Daalhuizen, J.; Cash, P.J. Defining the Behavioural Design Space. Int. J. Des. 2021, 15, 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Lalani, Y.; Godinho, A.; Ellison, K.; Joshi, K.; Wach, A.C.; Rana, P.; Wegier, P. Laying the foundation for iCANmeditate: A mixed methods study protocol for understanding patient and oncologist perspectives on meditation. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0290988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spitzer, R.L.; Kroenke, K.; Williams, J.B.W.; Löwe, B. A Brief Measure for Assessing Generalized Anxiety Disorder: The GAD-7. Arch. Intern. Med. 2006, 166, 1092–1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohen, S.; Williamson, G.M. Perceived Stress in a Probability Sample of the United States. In The Social Psychology of Health; Sage: Newbury Park, CA, USA, 1988; pp. 31–67. [Google Scholar]

- Feldman, G.; Hayes, A.; Kumar, S.; Greeson, J.; Laurenceau, J.P. Mindfulness and Emotion Regulation: The Development and Initial Validation of the Cognitive and Affective Mindfulness Scale-Revised (CAMS-R). J. Psychopathol. Behav. Assess. 2007, 29, 177–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russell, L.; Orellana, L.; Ugalde, A.; Milne, D.; Krishnasamy, M.; Chambers, R.; Livingston, P.M. Exploring Knowledge, Attitudes, and Practice Associated With Meditation Among Patients With Melanoma. Integr. Cancer Ther. 2017, 17, 237–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunt, C.A.; Hoffman, M.A.; Mohr, J.J.; Williams, A.L. Assessing Perceived Barriers to Meditation: The Determinants of Meditation Practice Inventory-Revised (DMPI-R). Mindfulness 2020, 11, 1139–1149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tversky, A.; Kahneman, D. Judgement under uncertainty: Heuristics and biases. Science 1974, 185, 1124–1131. [Google Scholar]

- Evans, J.S.B.T.; Stanovich, K.E. Dual-Process Theories of Higher Cognition: Advancing the Debate. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 2013, 8, 223–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanovich, K.E.; Toplak, M.E. Defining features versus incidental correlates of Type 1 and Type 2 processing. Mind Soc. 2012, 11, 3–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arıkan, F.; Uçar, M.A.; Kondak, Y.; Tekeli, A.; Kartöz, F.; Özcan, K.; Göksu, S.S.; Coşkun, H.Ş. Reasons for complementary therapy use by cancer patients, information sources and communication with health professionals. Complement. Ther. Med. 2019, 44, 157–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, S.; Janicki-Deverts, D. Who’s Stressed? Distributions of Psychological Stress in the United States in Probability Samples from 1983, 2006, and 2009. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2012, 46, 1320–1334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russell, L.; Ugalde, A.; Orellana, L.; Milne, D.; Krishnasamy, M.; Chambers, R.; Austin, D.W.; Livingston, P.M. A pilot randomised controlled trial of an online mindfulness-based program for people diagnosed with melanoma. Support. Care Cancer 2018, 27, 2735–2746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffman, C.; Baker, B. Effects of Mindful Self-Compassion Program on Psychological Well-being and Levels of Compassion in People Affected by Breast Cancer. Altern. Ther. Health Med. 2023, 29, 36–41. [Google Scholar]

- Chaturvedi, M.; Bajaj, M.K.; Singh, G.P.; Mitra, S. Positive well-being and usefulness of brief mindfulness-based intervention for pain in cancer. Int. J. Noncommun. Dis. 2023, 8, 137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, R.M.; Deci, E.L. Intrinsic and Extrinsic Motivations: Classic Definitions and New Directions. Contemp. Educ. Psychol. 2000, 25, 54–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gillison, F.B.; Rouse, P.; Standage, M.; Sebire, S.J.; Ryan, R.M. A meta-analysis of techniques to promote motivation for health behaviour change from a self-determination theory perspective. Health Psychol. Rev. 2019, 13, 110–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Radina, M.E.; Armer, J.M.; Stewart, B.R. Making Self-Care a Priority for Women At Risk of Breast Cancer–Related Lymphedema. J. Fam. Nurs. 2014, 20, 226–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCorkle, R.; Ercolano, E.; Lazenby, M.; Schulman-Green, D.; Schilling, L.S.; Lorig, K.; Wagner, E.H. Self-management: Enabling and empowering patients living with cancer as a chronic illness. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2011, 61, 50–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alsharif, F. Discovering the Use of Complementary and Alternative Medicine in Oncology Patients: A Systematic Literature Review. Evid.-Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2021, 2021, 6619243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruggeman-Everts, F.Z.; van der Lee, M.L.; de Jager Meezenbroek, E. Web-based individual Mindfulness-Based Cognitive Therapy for cancer-related fatigue—A pilot study. Internet Interv. 2015, 2, 200–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huberty, J.; Bhuiyan, N.; Neher, T.; Joeman, L.; Mesa, R.; Larkey, L. Leveraging a consumer-based product to develop a cancer-specific mobile meditation app: Prototype development study. JMIR Form. Res. 2022, 6, e32458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Humber River Health. Digital Equity in the ED: Q&A with Lead Researcher. 11 October 2024. Available online: https://www.hrh.ca/2024/10/11/digital-equity-in-the-ed/ (accessed on 9 May 2025).

- Mikolasek, M.; Witt, C.; Barth, J. Effects and Implementation of a Mindfulness and Relaxation App for Patients With Cancer: Mixed Methods Feasibility Study. JMIR Cancer 2021, 7, e16785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kubo, A.; Altschuler, A.; Kurtovich, E.; Hendlish, S.; Laurent, C.A.; Kolevska, T.; Li, Y.; Avins, A. A Pilot Mobile-Based Mindfulness Intervention for Cancer Patients and Their Informal Caregivers. Mindfulness 2018, 9, 1885–1894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dijkstra, K.; Pieterse, M.; Pruyn, A. Physical environmental stimuli that turn healthcare facilities into healing environments through psychologically mediated effects: Systematic review. J. Adv. Nurs. 2006, 56, 166–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iyendo, T.O.; Uwajeh, P.C.; Ikenna, E.S. The therapeutic impacts of environmental design interventions on wellness in clinical settings: A narrative review. Complement. Ther. Clin. Pract. 2016, 24, 174–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bronfenbrenner, U. Ecological systems theory. In Encyclopedia of Psychology; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2000; Volume 3, pp. 129–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | Participants (n = 148) |

| Demographic Characteristics | |

| Age, mean (SD) | 61.7 (12.6) |

| Female, % (n) | 51.4 (76) |

| Post-secondary education or higher, % (n) | 68.2 (101) |

| $30,000 income or more, % (n) * | 67.3 (76) |

| Married/common law, % (n) | 62.8 (93) |

| Part/Full Time Employed, % (n) | 39.9 (59) |

| Country of Birth, % (n) | |

| Canada | 28.4 (42) |

| Italy | 13.5 (20) |

| Philippines | 10.8 (16) |

| Jamaica | 10.1 (15) |

| India | 4.1 (6) |

| Other | 33.1 (49) |

| Christian, % (n) | 72.3 (107) |

| Clinical Characteristics | |

| Primary Cancer Diagnosis, % (n) | |

| Gastrointestinal cancer | 35.1 (52) |

| Breast cancer | 30.4 (45) |

| Blood cancer | 14.9 (22) |

| Respiratory cancer | 9.5 (14) |

| Genitourinary cancer | 8.1 (12) |

| Other | 2.0 (3) |

| Cancer Stage, % (n) | |

| I | 8.1 (12) |

| II | 14.9 (22) |

| III | 21.6 (32) |

| IV | 24.3 (36) |

| Unsure/don’t know | 31.1 (46) |

| Time Since Diagnosis, mean months (SD) | 26 (40) |

| First Diagnosis, % (n) | 83.1 (123) |

| PSS a, mean (SD) | 15.9 (7.1) |

| GAD b, mean (SD) | 5.4 (5.1) |

| CAMS c, mean (SD) | 29.7 (6.6) |

| Variables | ß (SE) | Odds Ratio (CI) | p |

| Model 1: Interest in Learning About Meditation (R2 * = 0.16) | |||

| Constant | 1.834 | 0.88 | 0.94 |

| Age | 0.016 | 0.98 (0.95–1.01) | 0.25 |

| PSS a | 0.043 | 0.99 (0.91–1.09) | 0.81 |

| GAD b | 0.052 | 1.05 (0.95–1.16) | 0.36 |

| CAMS c | 0.035 | 0.97 (0.90–1.03) | 0.33 |

| Number of Other Stress Activities | 0.13 | 1.33 (1.03–1.72) | 0.03 |

| Female | 0.409 | 2.06 (0.92–4.59) | 0.08 |

| Model 2: Interest in a DMT (R2 * = 0.23) | |||

| Constant | 1.77 | 0.91 | 0.96 |

| Age | 0.016 | 0.97 (0.94–1.00) | 0.05 |

| PSS a | 0.041 | 0.96 (0.88–1.04) | 0.30 |

| GAD b | 0.052 | 1.10 (1.00–1.22) | 0.06 |

| CAMS c | 0.033 | 1.01 (0.94–1.08) | 0.80 |

| Number of Other Stress Activities | 0.129 | 1.44 (1.12–1.86) | <0.01 |

| Female | 0.391 | 2.29 (1.06–4.93) | 0.03 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Godinho, A.; Dalmia, S.; Joshi, K.; Seo, C.; Laj, S.; Cacao, F.; Lun, L.; Wegier, P.; Rana, P. Listening in: Identifying Considerations for Integrating Complementary Therapy into Oncology Care Across Patient, Clinic, and System Levels—A Case Example of a Digital Meditation Tool. Curr. Oncol. 2025, 32, 682. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol32120682

Godinho A, Dalmia S, Joshi K, Seo C, Laj S, Cacao F, Lun L, Wegier P, Rana P. Listening in: Identifying Considerations for Integrating Complementary Therapy into Oncology Care Across Patient, Clinic, and System Levels—A Case Example of a Digital Meditation Tool. Current Oncology. 2025; 32(12):682. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol32120682

Chicago/Turabian StyleGodinho, Alexandra, Sanvitti Dalmia, Krutika Joshi, Christina Seo, Suzi Laj, Francis Cacao, Lisa Lun, Pete Wegier, and Punam Rana. 2025. "Listening in: Identifying Considerations for Integrating Complementary Therapy into Oncology Care Across Patient, Clinic, and System Levels—A Case Example of a Digital Meditation Tool" Current Oncology 32, no. 12: 682. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol32120682

APA StyleGodinho, A., Dalmia, S., Joshi, K., Seo, C., Laj, S., Cacao, F., Lun, L., Wegier, P., & Rana, P. (2025). Listening in: Identifying Considerations for Integrating Complementary Therapy into Oncology Care Across Patient, Clinic, and System Levels—A Case Example of a Digital Meditation Tool. Current Oncology, 32(12), 682. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol32120682