Primary Anastomosis Versus Hartmann’s Procedure in Obstructing Colorectal Cancer: A Retrospective Cohort Study

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

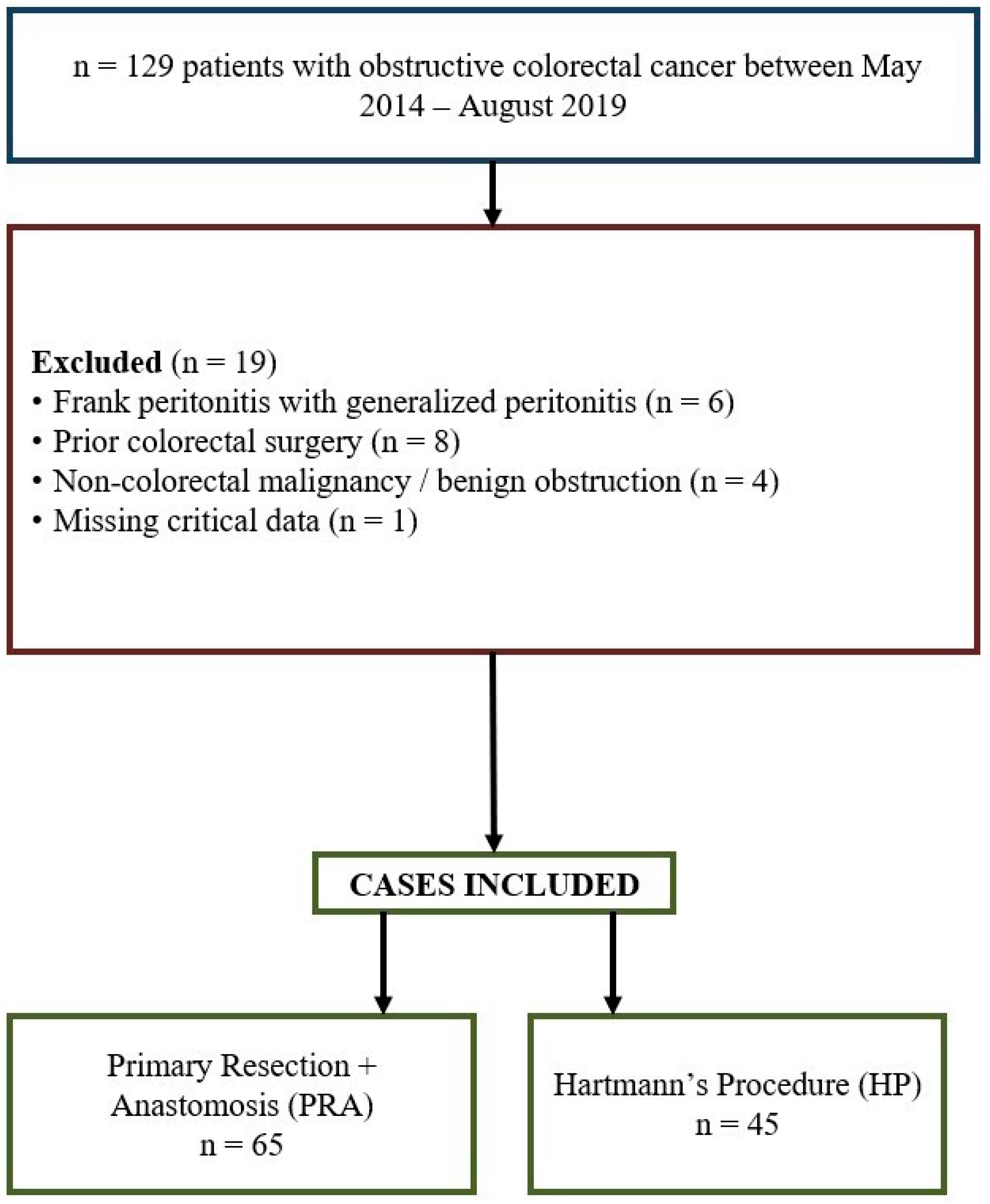

2. Methods

3. Surgical Procedures

4. Statistical Analysis

5. Results

5.1. Demographic Characteristics and Perioperative Outcomes

5.2. Comparison of PRA Cases with and Without Diverting Ostomy

5.3. Outcomes Based on Tumor Localization

5.4. Comparison of Subgroup Outcomes

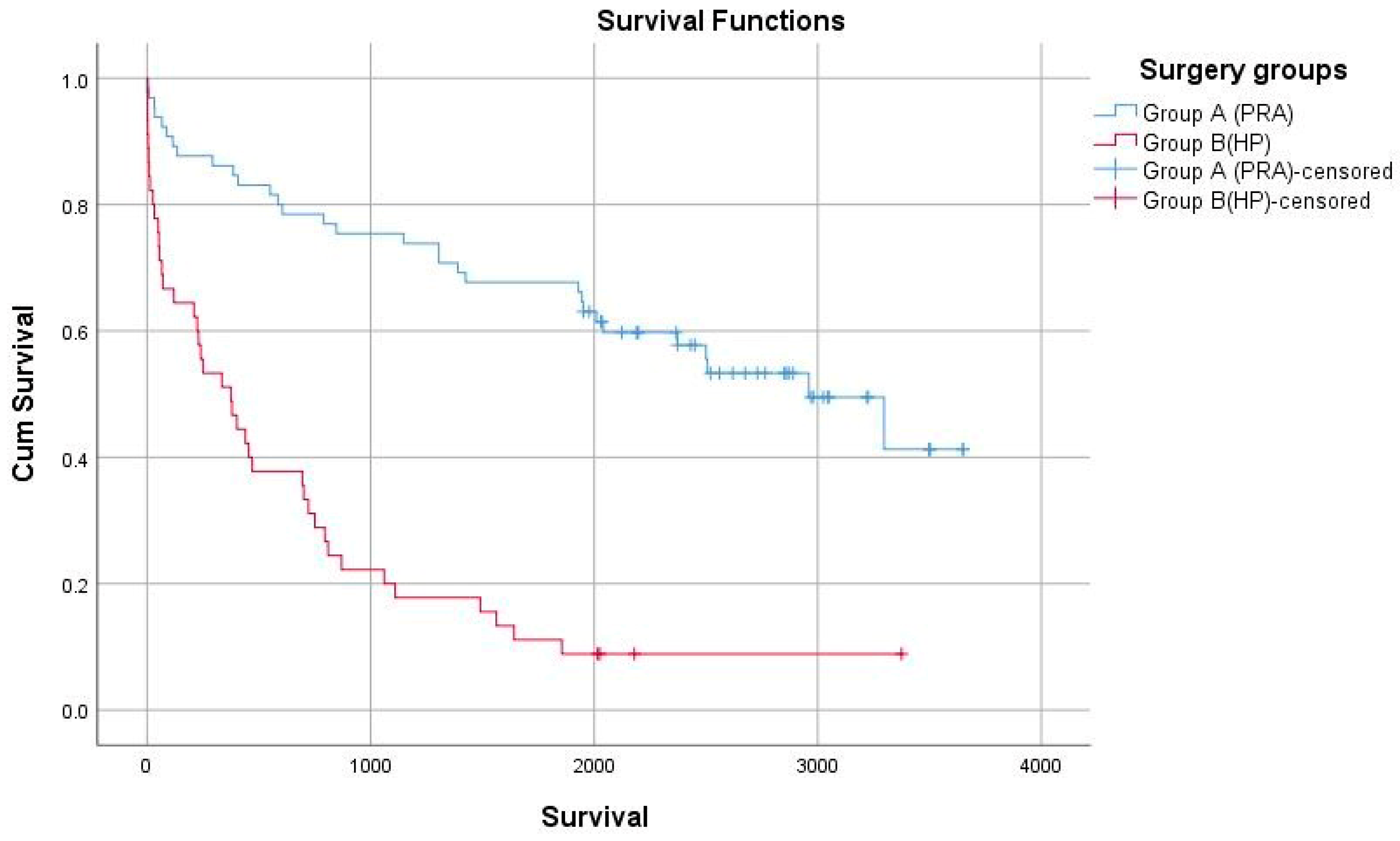

5.5. Long-Term Oncologic Outcomes

6. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Siegel, R.; Desantis, C.; Jemal, A. Colorectal cancer statistics, 2014. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2014, 64, 104–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siegel, R.L.; Giaquinto, A.N.; Jemal, A. Cancer statistics, 2024. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2024, 74, 12–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, R.-N.; Cho, H.-M.; Kye, B.-H. Management of obstructive colon cancer: Current status, obstacles, and future directions. World J. Gastrointest. Oncol. 2021, 13, 1850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McArdle, C.S.; McMillan, D.C.; Hole, D.J. The impact of blood loss, obstruction and perforation on survival in patients undergoing curative resection for colon cancer. Br. J. Surg. 2006, 93, 483–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulle, C.B.; Sengun, B.; Gok, A.F.K.; Ozgur, I.; Bayraktar, A.; Ertekin, C.; Deniz, A.B.; Keskin, M. Clinical outcomes of obstructive colorectal cancer patients during the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic. Turk. J. Trauma Emerg. Surg. 2023, 29, 663–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brillantino, A.; Skokowski, J.; Ciarleglio, F.A.; Vashist, Y.; Grillo, M.; Antropoli, C.; Herrera Kok, J.H.; Mosca, V.; De Luca, R.; Polom, K. Inferior mesenteric artery ligation level in rectal cancer surgery beyond conventions: A review. Cancers 2023, 16, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekinci, O.; Gapbarov, A.; Erol, C.I.; Beyazadam, D.; Eren, T.; Alimoglu, O. Resection and Primary Anastomosis versus Hartmann’s Operation in Emergency Surgery for Acute Mechanical Obstruction due to Left-Sided Colorectal Cancer. Indian J. Surg. 2021, 83, 428–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niemelainen, S.; Huhtala, H.; Ehrlich, A.; Kossi, J.; Jamsen, E.; Hyoty, M. Surgical and functional outcomes and survival following Colon Cancer surgery in the aged: A study protocol for a prospective, observational multicentre study. BMC Cancer 2021, 21, 698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dindo, D.; Demartines, N.; Clavien, P.A. Classification of surgical complications: A new proposal with evaluation in a cohort of 6336 patients and results of a survey. Ann. Surg. 2004, 240, 205–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makela, J.T.; Kiviniemi, H.; Laitinen, S. Risk factors for anastomotic leakage after left-sided colorectal resection with rectal anastomosis. Dis. Colon Rectum 2003, 46, 653–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDermott, F.D.; Heeney, A.; Kelly, M.E.; Steele, R.J.; Carlson, G.L.; Winter, D.C. Systematic review of preoperative, intraoperative and postoperative risk factors for colorectal anastomotic leaks. Br. J. Surg. 2015, 102, 462–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gomes, S.L.; Santos, P.M.D.d.; Costa Pereira, J.; Martins, S.F. Ileocolic anastomosis dehiscence in colorectal cancer surgery. Gastrointest. Disord. 2023, 5, 273–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, R.-N.; Mun, J.-Y.; Cho, H.-M.; Kye, B.-H.; Kim, H.-J. Assessment of colorectal anastomosis with intraoperative colonoscopy: Its role in reducing anastomotic complications. Biomedicines 2023, 11, 1162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallotta, V.; Palmieri, L.; Santullo, F.; Certelli, C.; Lodoli, C.; Abatini, C.; El Halabieh, M.A.; D’Indinosante, M.; Federico, A.; Rosati, A. Robotic Rectosigmoid resection with totally Intracorporeal colorectal anastomosis (TICA) for recurrent ovarian Cancer: A case series and description of the technique. J. Pers. Med. 2024, 14, 1052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carannante, F.; Piozzi, G.N.; Miacci, V.; Bianco, G.; Melone, G.; Schiavone, V.; Costa, G.; Caricato, M.; Khan, J.S.; Capolupo, G.T. Quadruple assessment of colorectal anastomosis after laparoscopic rectal resection: A retrospective analysis of a propensity-matched cohort. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 5092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frago, R.; Ramirez, E.; Millan, M.; Kreisler, E.; del Valle, E.; Biondo, S. Current management of acute malignant large bowel obstruction: A systematic review. Am. J. Surg. 2014, 207, 127–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van de Velde, C.J.; Boelens, P.G.; Tanis, P.J.; Espin, E.; Mroczkowski, P.; Naredi, P.; Pahlman, L.; Ortiz, H.; Rutten, H.J.; Breugom, A.J.; et al. Experts reviews of the multidisciplinary consensus conference colon and rectal cancer 2012: Science, opinions and experiences from the experts of surgery. Eur. J. Surg. Oncol. 2014, 40, 454–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elferink, M.A.; de Jong, K.P.; Klaase, J.M.; Siemerink, E.J.; de Wilt, J.H. Metachronous metastases from colorectal cancer: A population-based study in North-East Netherlands. Int. J. Color. Dis. 2015, 30, 205–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gujral, S.; Avery, K.N.; Blazeby, J.M. Quality of life after surgery for colorectal cancer: Clinical implications of results from randomised trials. Support Care Cancer 2008, 16, 127–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, Z.; Jiang, L.; Lu, A.; He, X.; Zuo, Y.; Yang, J. Living with a permanent ostomy: A descriptive phenomenological study on postsurgical experiences in patients with colorectal cancer. BMJ Open 2024, 14, e087959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ugai, T.; Akimoto, N.; Haruki, K.; Harrison, T.A.; Cao, Y.; Qu, C.; Chan, A.T.; Campbell, P.T.; Berndt, S.I.; Buchanan, D.D.; et al. Prognostic role of detailed colorectal location and tumor molecular features: Analyses of 13,101 colorectal cancer patients including 2994 early-onset cases. J. Gastroenterol. 2023, 58, 229–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breitenstein, S.; Rickenbacher, A.; Berdajs, D.; Puhan, M.; Clavien, P.A.; Demartines, N. Systematic evaluation of surgical strategies for acute malignant left-sided colonic obstruction. Br. J. Surg. 2007, 94, 1451–1460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hsu, T.C. Comparison of one-stage resection and anastomosis of acute complete obstruction of left and right colon. Am. J. Surg. 2005, 189, 384–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, E.M.; Park, J.H.; Kim, B.C.; Son, I.T.; Kim, J.Y.; Kim, J.W. Self-expandable metallic stents as a bridge to surgery in obstructive right-and left-sided colorectal cancer: A multicenter cohort study. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee-Kong, S.; Lisle, D. Surgical Management of Complicated Colon Cancer. Clin. Colon Rectal Surg. 2015, 28, 228–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omoto, R. Comparison Between Primary Anastomosis Without Diverting Stoma and Hartmann’s Procedure for Colorectal Perforation: A Retrospective Observational Study. Cureus 2024, 16, e58402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shigeta, K.; Baba, H.; Yamafuji, K.; Kaneda, H.; Katsura, H.; Kubochi, K. Outcomes for patients with obstructing colorectal cancers treated with one-stage surgery using transanal drainage tubes. J. Gastrointest. Surg. 2014, 18, 1507–1513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variables | Group A (PRA) n = 65 | Group B (HP) n = 45 | p | Effect Size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean ± SD | Mean ± SD | |||

| Age [year] | 57.06 ± 16.6 | 65.09 ± 16.5 | 0.560 | 0.49 |

| Survival [day] | 1969 ± 1113 | 626 ± 759 | 0.001 | 1.38 |

| Hospitalization days | 8.7 ± 4.1 | 11.2 ± 15.2 | 0.020 | 0.55 |

| Laboratory parameters | Mean ± SD | Mean ± SD | p | |

| WBC [×103/μL] | 9.79 ± 3.51 | 9.31 ± 4.77 | 0.546 | 0.12 |

| Hb [g/dL] | 12.24 ± 2.29 | 12.44 ± 2.37 | 0.660 | 0.09 |

| Alb | 3.40 ± 0.765 | 3.01 ± 0.871 | 0.105 | 0.48 |

| CA 19-9 | 25.33 ± 43.06 | 216.11 ± 440.721 | 0.004 | 0.67 |

| CEA | 9.06 ± 17.84 | 204.07 ± 507.27 | 0.009 | 0.56 |

| CRP [mg/L] | 58.29 ± 51.48 | 64.87 ± 73.78 | 0.619 | 0.11 |

| Creatinine | 0.81 ± 0.21 | 0.92 ± 0.37 | 0.317 | 0.38 |

| Urea | 33.51 ± 16.67 | 43.04 ± 22.37 | 0.024 | 0.49 |

| ASA Score | (n%) | (n%) | ||

| I-II | 42 (64%) | 15 (33%) | 0.040 | 3.65 |

| III-IV | 23 (36%) | 30 (66%) | ||

| Tumor localization | (n%) | (n%) | ||

| Right sided | 20 (30%) | 3 (6%) | 0.002 | 6.22 |

| Left sided | 45 (70%) | 42 (93%) | ||

| Number of metastasis | (n%) | (n%) | ||

| 1 organ | 19 (29.2%) | 14 (31.1%) | 0.967 | 0.90 |

| 2 or more organs | 4 (6.2%) | 3 (6.7%) | ||

| Need for repeat surgery | 16 (24.6%) | 20 (44.4%) | 0.029 | 0.41 |

| Complications | 22 (33%) | 30 (66%) | 0.003 | 0.26 |

| Gender [M/F] n/% | [31/34, (48%/52%) | 25/20, (56%/44%) | 0.650 | 0.73 |

| Surgery Time | 122.37 ± 37.10 | 99.67 ± 45.56 | 0.003 | 0.56 |

| Adjuvant therapy | ||||

| Present | 36 (55.4%) | 17 (37.8%) | 0.069 | 2.04 |

| Absent | 29 (44.6%) | 28 (62.2%) |

| Outcomes Value | PRA Case with Ostomy n = 4 | PRA Case Without Ostomy n = 61 |

|---|---|---|

| Mean ± SD | Mean ± SD | |

| Age, years | 62 ± 16.9 | 56.7 ± 16.2 |

| Hemoglobin | 14.77 ± 1.75 | 12.07 ± 2.24 |

| Albumin | 2.60 ± 1.69 | 3.47 ± 0.67 |

| CRP | 84.57 ± 68.84 | 55.95 ± 49.99 |

| Hospitalization days | 10.2 ± 3.1 | 7.1 ± 2.1 |

| ASA Score | n (%) | n (%) |

| I-II | 4 (100%) | 38 (62%) |

| III-IV | 0 | 23 (38%) |

| Tumor localization | ||

| Right-sided | 0 | 20 (32%) |

| Left-sided | 4 (100%) | 41 (67%) |

| Complications | ||

| Surgical site infection | 0 | 5 (8.2%) |

| Multiorgan failure | 0 | 0 |

| Anastomosis leakage | 0 | 5 (8.2%) |

| Re-operation | 3 (75%) | 13 (21.3%) |

| Mortality | 0 | 2 (3.3%) |

| Variable | Group A1 | Group A2 | Group B1 | Group B2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hospitalization day, [Mean ± SD] | 8.89 ± 4.18 | 7 ± 2.5 | 16.6 ± 9.6 | 6.04 ± 6.35 |

| Recurrence [n (%)] | 2 (3.3%) | 0 | 1 (4.5%) | 2 (8.7%) |

| Metastasis rates [n (%)] | 23 (37.7%) | 0 | 6 (27.3%) | 11 (47.8%) |

| Complications [n (%)] | 19 (31.1%) | 3 (75%) | 19 (86%) | 11 (47.8%) |

| Need for repeat surgery [n (%)] | 13 (21.3%) | 3 (75%) | 13 (59.1%) | 7 (30.4%) |

| Tumor localization [Right sided, n (%)] | 20 (32.8%) | 0 | 2 (9.1%) | 1 (4.3%) |

| Tumor localization [Left sided, n (%)] | 41 (67.2%) | 4 (100%) | 20 (90.9%) | 22 (95.7%) |

| Co-morbidities [n (%)] | 14 (22.9%) | 0 | 4 (18%) | 7 (30.4%) |

| Surgical site infection [n (%)] | 5 (8.2%) | 0 | 3 (13.6%) | 2 (8.7%) |

| 1-Year survival rate (%) | 80.32% | 100% | 77.2% | 65.2% |

| 5-Year survival rate (%) | 40.9% | 25% | 36.3% | 26% |

| Variables | Group A (PRA) n = 65 | Group B (HP) n = 45 | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | n (%) | ||

| Recurrence | 2 (3.1%) | 3 (6.7%) | 0.370 |

| Metastasis rates | 23 (35%) | 17 (37%) | 0.960 |

| Survival | % | % | p |

| 30-day survival rate | 96.9 | 91.1 | 0.460 |

| 1-Year survival rate | 84.6 | 66.6 | 0.001 |

| 5-Year survival rate | 33.8 | 22.2 | 0.003 |

| Variable | B | SE | p Value | HR | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Surgery groups (PRA vs. HP) | −1.102 | 0.382 | 0.004 | 0.332 | 0.157–0.702 |

| ASA score | −0.013 | 0.225 | 0.953 | 0.987 | 0.635–1.533 |

| CEA | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.523 | 1.000 | 0.999–1.002 |

| CA 19-9 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.976 | 1.000 | 0.998–1.002 |

| Tumor localization | 0.368 | 0.421 | 0.382 | 1.445 | 0.633–3.298 |

| Age | 0.016 | 0.012 | 0.174 | 1.016 | 0.993–1.039 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Aras, A. Primary Anastomosis Versus Hartmann’s Procedure in Obstructing Colorectal Cancer: A Retrospective Cohort Study. Curr. Oncol. 2025, 32, 636. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol32110636

Aras A. Primary Anastomosis Versus Hartmann’s Procedure in Obstructing Colorectal Cancer: A Retrospective Cohort Study. Current Oncology. 2025; 32(11):636. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol32110636

Chicago/Turabian StyleAras, Abbas. 2025. "Primary Anastomosis Versus Hartmann’s Procedure in Obstructing Colorectal Cancer: A Retrospective Cohort Study" Current Oncology 32, no. 11: 636. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol32110636

APA StyleAras, A. (2025). Primary Anastomosis Versus Hartmann’s Procedure in Obstructing Colorectal Cancer: A Retrospective Cohort Study. Current Oncology, 32(11), 636. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol32110636