1. Introduction

Hematological cancers affect nearly 7% of the global population diagnosed with cancer [

1]. Over recent years, the 5-year survival rate for these cancers has seen a remarkable rise, increasing by 20–50 percentage points [

2]. This significant improvement in survival can be attributed to groundbreaking advancements in medical care and treatments, particularly the innovations in cellular therapy (such as chimeric antigen receptor T-cell therapy (CAR-T)) and Hematopoietic Cell Transplantation (HCT) [

3,

4]. However, unlike individuals diagnosed with solid tumors, who often follow a more predictable disease course, those with hematological malignancies face a highly uncertain trajectory due to factors such as poor prognosis, high recurrence rates, and the complexity of treatments [

5,

6,

7].

Individuals diagnosed by hematological cancer often experience greater treatment-related toxicities, psychological distress, and a lower quality of life [

7,

8]. They also report more severe symptoms, higher hospitalization rates, and more frequent admissions to intensive care units [

9]. It is documented that this population faces numerous unmet needs at the end of care pathways, particularly related to emotions, fatigue, and concerns about cancer recurrence [

10,

11]. These individuals experience different and unique needs at various stages of the disease, as the episodic nature of cancer care and treatment evolves [

7,

12]. However, it is difficult for them to share their concerns including emotional, physical, and other personal needs, due to the psychological impact of cancer diagnosis and treatment [

13]. Many hide their emotions and needs from their families in effort to minimize distress and other psychological burdens on their loved ones [

14,

15]. They may struggle to meet their own needs due to the shock of diagnosis, the distress of hospitalization, and feeling lost both in the healthcare system and in their daily lives [

16]. Moreover, healthcare support in hematology-oncology often falls short in recognizing the unique experiences of these individuals and providing timely, personalized support [

17].

For cancer survivors, the lack of tailored support, combined with their frustration over unmet needs, diminishes their sense of control, adding an additional burden to their cancer journey [

13].

Nevertheless, accompanying patients (APs)—also known as peer supporters—who have personally experienced cancer, can help individuals diagnosed with cancer express their feelings more openly, strengthen their resilience, and alleviate common challenges such as depression and anxiety [

18,

19]. They can act as patient advisors, drawing on their firsthand knowledge of managing the disease, navigating healthcare services, and engaging with healthcare professionals (HCPs) [

20]. By sharing their experiences, they provide a valuable source of support for patients and HCPs, which not only strengthens their own well-being and confidence but also improves the health of patients currently undergoing cancer treatment [

20]. They can contribute across the entire cancer care continuum, promoting patient engagement at every stage, assisting with treatment adherence, and providing guidance to both patients and their families [

21,

22]. Therefore, the support of APs, which allows for authentic experience sharing, has become an indispensable resource in cancer care [

23].

Several challenges have hindered the widespread integration of APs in cancer care, including the diverse information needs of patients with different cancer types and the lack of structured guidance and training [

24,

25]. In this context, the Government of Quebec (Canada) has made patient partnership a strategic priority in its health and social services system, supported by concrete policy actions and legislative reforms aimed at restructuring healthcare institutions to foster its integration into clinical, organizational, and strategic practices [

26]. Building on this commitment, Province of Quebec has also emerged as a pioneer through the implementation of peer support programs such as PAROLE-Onco, which has developed and documented effective strategies for integrating APs into clinical oncology teams, particularly for specific cancer populations like individuals with breast cancer [

27]. However, this type of support has not yet been implemented or evaluated in hematological oncology, particularly in the context of cellular therapies such as HCT or CAR-T cells.

To fully engage APs in supporting cancer survivors, it is essential to develop a structured AP support system along with standardized guidance and information [

18,

24,

28]. Therefore, well-structured AP support and tailored guidance are needed to better understand and address the unmet needs of individuals affected by cancer, particularly those who have received CAR-T therapy or allogeneic HCT, as these treatments often lead to severe complications, prolonged hospitalizations and greater unmet needs.

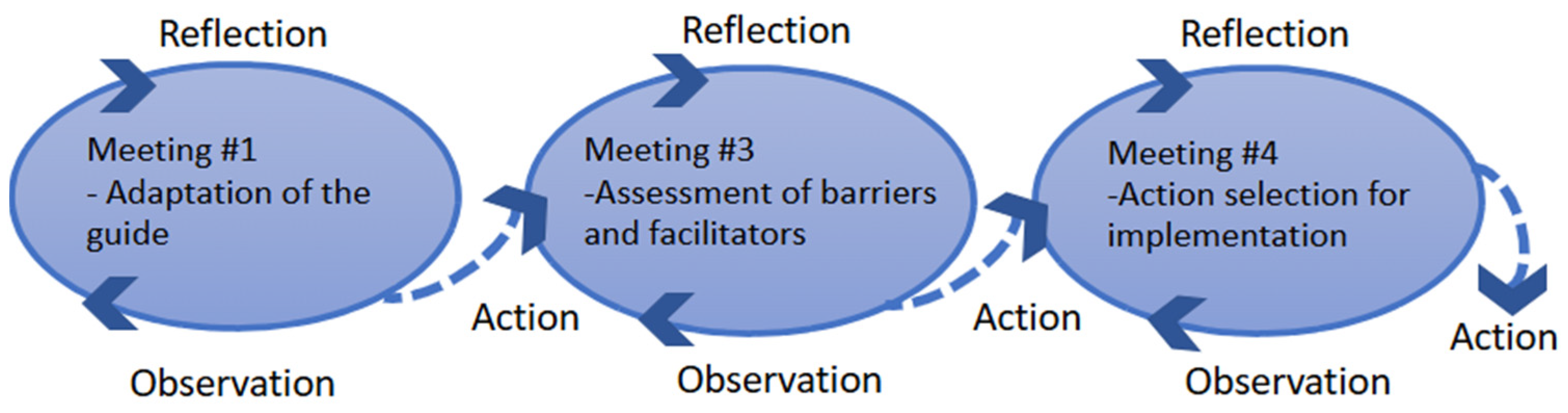

To address these challenges, our team has developed support guides to outlining two structured support pathways provided by trained APs during key stages of the care pathway (e.g., start of treatments/hospitalization, end of treatment). These pathways were co-designed in collaboration with key stakeholders—including APs, HCPs, and managers—to tailor the components of structured support tailored to the care pathways of CAR-T and allogeneic HCT. This paper reports on the anticipated needs to be addressed by an AP, the role of APs, and the key facilitators, challenges, and strategies for the implementation of structured support offered by an AP.

3. Results

A total of 16 individuals participated in the project, including individuals living beyond hematological cancer (n = 9), HCPs (n = 6), and one oncology manager (n = 1).

Among the 9 individuals living beyond hematological cancer, 4 had undergone allogeneic HCT, and 5 had received CAR-T therapy. The mean age was 50 years (median: 47.5, range: 37–67) for the allogeneic HCT group and 57 years (median: 64, range: 32–71) for the CAR-T group. All 5 APs in the CAR-T group had been diagnosed with lymphoma, while in the allogeneic HCT group, 3 had leukemia and 1 had aplastic anemia. The average time since diagnosis was 13.5 years (range: 6–31 years) for the allogeneic HCT group and 5 years (range: 4–7 years) for the CAR-T group.

The 6 HCPs represented four different professions: nurse navigators (

n = 3), hematologist (

n = 1), a psychologist (

n = 1), and a medical technologist (

n = 1). The average oncology work experience was 13.5 years (range: 4–22 years).

Table 3 and

Table 4 report all participants’ characteristics.

Group discussions highlighted the anticipated need that APs can help address throughout the CAR-T or allogeneic HCT care pathway. They also explored the role of the AP, identified both facilitators and challenges to implement this new support model, and proposed potential solutions. The following section describes these themes in detail.

3.1. Needs That APs Can Help Anticipate

Discussions revealed that APs can support a broad range of needs—practical, social, emotional, informational, and psychological.

Practical concerns were often related to self-management of the illness, returning to school or work, and financial issues. One participant emphasized the importance of discussing life after treatment:

“After the transplant, there is always something—either anti-rejection medications, maintenance chemotherapy, or other ongoing treatments. Some people experience side effects that persist over time, so this must be addressed.”

(P2)

Social concerns centered around the value of being heard, sharing experiences with others, and breaking isolation through peer interaction. Participants also stressed the importance of extending support to family members and relatives. One participant noted the absence of peer connection during their own experience and welcomed the opportunity this project offers:

“Right now, there isn’t really an option for patients to meet and get to know each other. What the patient-partner can bring is a way to fill that gap.”

(P3)

Informational concerns discussed included the sharing of lived experiences and knowledge gained by APs. In the CAR-T group, participants stressed the importance of conveying realistic expectations about treatment and avoiding overly optimistic or sharing “sugar-coated” stories.

Psychological concerns were also prominent. Participants noted that APs could help patients manage fears of recurrence, feelings of lost control, and the emotional adjustment to life changes brought on by cancer. One participant shared how their life was profoundly altered upon diagnosis:

“It was the day I got my diagnosis. The ER doctor told me, ‘Ma’am, your life has just changed from this day forward.’ That’s when I began to grieve and mentally prepare myself—because you have to come to terms with it.”

(P8)

3.2. AP Role and Benefits

The role of the AP is primarily perceived as one of support and referral, with an emphasis on maintaining clear boundaries concerning the responsibilities of HCPs. Participants also emphasized the importance of clearly establishing personal boundaries as part of the AP role, warning that failing to do so could lead to compassion fatigue. They also noted that APs often face fluctuating health conditions—such as fatigue and immunosuppression—which require adaptive approaches to the support they provide. While many expressed a willingness to help others, some acknowledged that not all APs may feel comfortable with every aspect of the role, and that levels of competence in areas such as reassurance, coaching, and encouragement can vary. These individual differences must be recognized and clearly defined from the outset.

Furthermore, the non-professional status of APs within the clinical care team imposes inherent limitations, as reflected in the following participant’s comment:

“Patients [receiving support] should also know that we do not claim to be doctors or nurses.”

(P3)

“We always remain within the boundaries of the patient-partner role.”

(P5)

Nonetheless, participants acknowledged several potential benefits of a structured support program. These include assistance provided to both patients and APs, improved continuity and complementarity of care in relation to the work of HCPs, and a reduction in the workload of clinical staff. The guidance offered to APs, along with structured tools such as an implementation guide, was viewed as essential for ensuring effective involvement. As one HCP participant observed:

“I see that [support from an AP] can be an added value for professionals. You know, right away, it’s an extra source of support. So personally, I see it as helpful in the long run. It will definitely lighten the workload of healthcare professionals.”

(P9)

3.3. Challenges and Strategies for Achieving Sustainable Implementation

Challenges were discussed within the groups (

Table 5) as well as their solutions (

Table 6). These results were framed across four key contexts: APs, patients, HCPs, and the healthcare organization.

3.3.1. AP Context

Participants noted that APs may feel pressure to help others, which could increase their risk of emotional exhaustion. To address this, they emphasized the importance of comprehensive training, external support, and practical tools. Participants also highlighted that APs should not independently identify patients to support; instead, they require guidance from the healthcare team. A further concern was the potential for APs to unintentionally share inaccurate information based on their personal experiences. To mitigate this, training and standardized tools—such as a shared lexicon—were identified as essential.

3.3.2. Patient Context

In relation to patients, participants stressed the need for APs to avoid overwhelming individuals with excessive information. They emphasized the importance of providing patients with personalized, accessible information that is relevant to their needs and delivered at a pace appropriate for them.

3.3.3. Healthcare Professional Context

Challenges in this context included the potential need for HCPs to reframe or clarify information provided by APs, especially to avoid misinterpretation or misinformation. Again, proper training and use of the support guide were highlighted as solutions. Participants also recommended regular reminders about each person’s role in maintaining clarity within the care team. Another challenge raised was determining the optimal timing for offering AP support to patients undergoing cellular therapy. Participants advocated for introducing AP support at multiple moments throughout the cancer care pathway.

3.3.4. Organizational Context

At the organizational level, concerns were raised about ensuring the support guide remains up to date after the research project concludes. Participants suggested involving APs in quality committees within the cancer program and holding regular meetings among APs to ensure continuity and improvement of the support program.

4. Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first initiative to integrate peer support (AP support) for individuals undergoing cellular therapies in Canada. Our findings underline that APs are uniquely positioned to address a wide range of unmet needs among patients who have undergone complex therapies such as CAR-T or HCT. In our study, participants, including individuals living beyond hematological cancer, HCPs, and managers, consistently emphasized the anticipated positive and tangible impact of APs’ presence. They highlighted that such support could help patients feel genuinely heard, emotionally supported, and better equipped to navigate the complexities of their care journey. This shared expectation underscores the perceived value of AP integration as a promising component of supportive care in hematological oncology context. These findings are consistent with the qualitative study by Amonoo et al. [

39] which documented how patients who had undergone HCT perceived the benefits of peer support, including emotional reassurance, assistance in managing expectations and uncertainty, and broader social support. Similarly, recent studies have also shown that APs can effectively respond to emotional, informational, cognitive, and navigational needs, thereby fostering patient empowerment in the context of breast cancer care [

23].

Our results underline that patients often struggle to process and retain the large volume of information they receive, confirming prior findings that patients can feel overwhelmed and unable to absorb critical medical content. In line with previous studies, our participants emphasized the need for information that is personalized, timely, and adapted to each patient’s rhythm, needs, and preferences [

40,

41]. As highlighted in a peer support project for individuals undergoing HCT, peers can help digest the large volume of information by translating it from their patient pocket documentation [

42]. This strategy not only improves the recall and relevance of information delivered but also enhances the overall quality of care and patient experience.

However, our results also highlighted challenges related to the integration of APs—most notably, the emotional burden they experience when role boundaries are unclear, as emphasized in previous initiatives [

43,

44]. The solutions proposed by participants, in our study align with the findings of Chudyk et al. [

45], who emphasized that the success and impact of peer support rely on clearly defined roles, appropriate training, and organizational support to prevent overstepping and compassion fatigue. In response to these challenges, our participants also recommended the use of structured tools—such as the support guide co-developed by the teams—to define roles and clarify expectations. They emphasized the importance of providing dedicated support to safeguard the well-being of both APs and patients. One example is the Cancer Partnership Hub [

46], implemented in the hospital where the project took place. This initiative provides structured support to a team of APs through a combination of dedicated guidance, specialized training, and community-building activities. A resource person and a committee of practice are available to answer questions, facilitate debriefing sessions, and offer ongoing follow-up, helping APs navigate their roles effectively and remain within scope. Mandatory and ongoing training sessions focus on the AP role and the patient partnership approach, ensuring clarity around responsibilities and boundaries. Weekly meetings are held to foster a sense of community and promote resilience among APs. All APs are enrolled as volunteers (no financial compensation) and undergo background checks prior to their involvement, as well as an informal interview. Patient–AP matching is conducted by a clerk, based on similarities in diagnosis or lived experience. In cases where a match is not optimal, a reassignment process is available, coordinated by the resource person to ensure a better fit and maintain the quality of support provided. The Cancer Partnership Hub also anticipates and accommodates changes in APs’ availability. Since several APs are part of the team, flexible options allow one or more members to take a temporary or permanent pause if they experience a recurrence or need to focus on personal treatment, while maintaining continuity of the service. These measures are designed to protect APs’ well-being and ensure they are not pressured to continue beyond their capacity. Despite the innovative nature of peer support, its success relies on willingness, organization, and governance, as outlined above.

Another challenge identified in our study relates to the risk of misinformation when APs lack adequate knowledge or training, a concern echoed by Holdren et al. [

47]. Consistent with the recommendations of previous studies, our findings underscore the need for APs to receive tailored training, access to evidence-based support guides and lexicons, and ongoing supervision to ensure the consistency, safety, and accuracy of the support they provide [

47,

48]. Once again, initiatives such as the Cancer Partnership Hub [

46] could play a key role in providing high-quality training and ongoing guidance for APs alongside resources and documentation developed through the pioneering PAROLE-Onco program.

Finally, our study raised organizational concerns—particularly regarding the sustainability of the AP program beyond the research phase—which mirror the reflections found in the study by Paillard-Brunet et al. [

49]. These authors highlight the importance of ethical and institutional oversight of partnership models to ensure that the contributions of APs are recognized, valued, and embedded in structured governance. In addition, Ferville et al. [

50] note that HCPs’ reluctance, lack of time, and established work routines can hinder the integration of APs into clinical routine. Therefore, implementation strategies must be planned to support the long-term sustainability of the AP role. The strategies proposed in our study—such as involving APs in quality committees and holding regular meetings—offer concrete ways to overcome barriers and contribute to the long-term sustainability of such initiatives. In this regard, the implementation guide of the PAROLE-Onco initiative provides structured tools and best-practice recommendations to support the implementation, evaluation, and improvement of peer support programs, and can be adapted to other cancer trajectories [

27]. This approach is fully in line with the principles of the Montreal Model of Partnership in Health [

51], which emphasizes the importance of involving patients in strategic quality committees to ensure their voices are heard and to facilitate meaningful change [

52].

The strength of this project lies in its co-development with both patients and HCPs. We successfully ensured the equal representation of both groups in each working session. This shared perspective enabled early negotiation of the content and boundaries of the APs’ support guides. Framing group discussions within an implementation science framework was an essential strategy to identifying potential barriers to the uptake of this innovative intervention.

However, several limitations should be acknowledged. First, one physician participated in the working group, which may influence the broader adoption of the intervention. Nonetheless, all relevant stakeholders were informed of the project and took part in informational sessions. Second, as the results are based on group discussions, quieter participants may have been less engaged or more likely to agree with the majority to avoid conflict. Lastly, these findings should be interpreted within the context of the Quebec (Canada) cancer care system, where specialized cancer services are publicly funded and accessible.

The next step in this project is to evaluate the implementation of structured support provided by APs. A multiple-case study is currently underway at a cellular therapy centre in the Montreal area. Data collection includes questionnaires, administrative data, and interviews with patients, APs, and HCPs. These results will inform the scalability and broader applicability of this promising initiative.