1. Introduction

A central challenge in patient education is readability. Only about 12% of adults demonstrate proficient health literacy, while most medical information materials are written at a complexity exceeding readability level recommended by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and American Medical Association (AMA), i.e., sixth or eighth grade reading levels [

1]. Individuals with lower educational attainment face disproportionate barriers in comprehending complex health information, which may contribute to inequities in shared decision-making [

2]. This issue is particularly critical in urooncology, where high clarity in communication is demanded by the rapid emergence of novel therapeutic evidence, surveillance protocols and the profound consequences that miscommunication could carry in cancer care. Although recent work suggests that LLMs can simplify complex language and thereby enhance the readability of patient education materials, evidence from real-world clinical settings is heterogeneous [

3].

Studies consistently show that patient education materials (PEMs) for urological cancers exceed recommended reading level thresholds. The Flesch–Kincaid Reading Ease (FRE) is a readability metric ranging from 0 to 100 that estimates the school grade level required to understand a given text, with higher scores indicating simpler text and improved accessibility [

4]. For example, a score between 70 and 80 is equivalent to school grade level 8. Rodler et al. demonstrated that most urooncological PEMs fail to reach an FRE-Score ≥ 70 [

2]. Similarly, Pruthi et al. reported average readability levels of grade 11.7 for online urooncology resources [

5]. These findings underscore a substantial gap between current and recommended standards in PEMs.

Large language models (LLMs) in the form of chatbots are increasingly investigated as conversational tools for patient education, including applications in urooncology [

6]. By allowing natural language queries and generating contextualized answers, LLMs are positioned to complement or even replace traditional search engines as a primary source of medical information for patients [

7,

8]. Moreover, LLMs are dynamic and can be adapted to the specific needs of the user when prompted, offering the potential for personalized and accurate health communication. Recent evaluations suggest that patients prefer chatbots over search engines for user-friendliness and quality of information [

9].

However, the challenge of subpar readability extends to LLM-generated PEMs. Prior work has assessed the quality and readability of such materials in controlled or in-silico settings. For example, Hershenhouse et al. found that LLM outputs on prostate cancer often exceeded typical comprehension levels [

10,

11]. This challenge can be addressed as exemplified by two recent studies. Ganjavi et al. recently presented the first randomized controlled trial showing that LLMs can simplify scientific abstracts, and Rodler et al. reported that GPT-4 can significantly improve the objective readability of PEMs with the use of evidence-based reference knowledge and prompt engineering [

12,

13].

Building on this line of research, the Interaction of Patients with Large Language Models (IPaLLM) study was designed to evaluate chatbot use in a clinical setting [

9,

14,

15]. Here, urological patients engaged in unscripted conversations with a speech-based GPT-4 chatbot during routine care visits. The aim of this study is to assess the correlation between objective and perceived readability of outputs generated by a GPT-4-based LLM in response to patient inquiries. Patients interacted with a chatbot in unscripted conversations to obtain medical information. In addition, we report descriptive data on the conversation transcripts and demographic characteristics of the participants. We hypothesize that the conversational, speech-to-speech delivery of information by the chatbot may enhance perceived readability, even when the objectively measured readability levels remain comparatively complex.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Participants

This explorative analysis was conducted using data collected as part of the prospective clinical trial IPaLLM (Interaction of Patients with Large Language Models), officially registered with the German Clinical Trial Registry (DRKS-ID: 00034906, registered on 16 of August 2024). The trial prospectively enrolled adult patients attending urological consultation at the University Medical Center Mannheim, excluding those with cognitive impairments or psychiatric conditions. Eligible participants engaged in conversation-like interactions with a speech-to-speech LLM-powered chatbot (GPT-4, OpenAI) and subsequently completed a survey. This work shares a unified study design and methodology with previously published parts of the clinical trial, which examined patients’ confidence in LLM capabilities as well as their perceptions of usefulness, quality, and empathy when interacting with a chatbot for medical information-seeking [

9,

14,

15].

The current study specifically investigates chatbot–patient transcripts with regard to objective readability metrics and perceived readability, thus extending our prior research that predominantly assessed the patient’s perspective. This evaluation was approved by the institutional ethics review board of the Medical Faculty Mannheim, Ruprecht-Karls University of Heidelberg (proposal number: 2023-687, approval date: 27 February 2024) and adhered to the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki.

2.2. Study Procedure

After providing informed consent, participants received an introduction to LLMs and then interacted with a GPT-4 powered chatbot on a tablet, asking any medical question relevant to their current situation. No specific prompt engineering was undertaken to increase readability. The chatbot session was followed by a structured post-interventional survey, including the assessment of the perception of output readability. Demographic data, including age and educational attainment, were non-mandatory items collected at the end of the procedure. This analysis evaluated objective readability (FRE/LIX/WSF) and patient-reported perceived readability. Clinical correctness (relative to guideline statements or local protocols) was not assessed. Conversations were conducted immediately prior to the clinical encounter, allowing the treating physician to review and correct information as needed.

2.3. Questionnaire Development

The survey instrument used in this study was developed based on the existing literature and refined through six semi-structured expert interviews, comprising both patients and board-certified urologists. The resulting questionnaire was tested in a pilot study involving 20 medical students. The survey assessed perceived readability across four items: “understandability of technical language” and “content” as well as “clarity” and “explanation sufficiency”. Agreement for items was captured using a Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree), survey items are displayed in

Table 1.

2.4. Conversation Analysis

First, transcripts of chatbot–patient conversations were evaluated descriptively. Conversations were classified by discussed topics (e.g., disease, procedure and general medical theme if applicable) as well as analyzed for total word and sentence count. Secondly, readability was assessed objectively using three established indices: Flesch Reading Ease (FRE) [

4], Lesbarkeitsindex (LIX) [

16], and Wiener Sachtextformel (WSF) [

17]. Given that all interviews were conducted in German, the adapted formula FRE

German for the German language was employed [

18]. In addition, the LIX and WSF readability indices were selected as complementary measures. Their results were later compared to those obtained from the FRE

German analysis.

2.5. Readability Indices

This section outlines the calculation formulas of the readability indices applied in this study.

The FRE

German is calculated as FRE

German = 180 − ASL − (58.5 × ASW), where ASL denotes the average sentence length in words and ASW the average number of syllables per word [

18]. Higher values indicate greater ease of reading, with scores above 80 reflecting easy-to-read texts and values below 30 denoting very difficult academic-level text. Throughout this manuscript, FRE

German is hereafter referred to as FRE. Both NIH and AMA recommend an FRE of ≥70 for PEMs.

The LIX formula is LIX = (A/B) + (C × 100/A), where A represents the total number of words, B the number of sentences, and C the number of long words with more than six letters [

16]. Here, higher scores correspond to more complex texts, with values above 60 considered very difficult, between 40 and 50 easy, and below 40 very easy.

The WSF is defined as WSF1 = 0.1935 × MS + 0.1672 × SL + 0.1297 × IW − 0.0327 × ES − 0.875, where MS denotes the percentage of words with three or more syllables, SL the average sentence length in words, IW the percentage of words longer than six letters, and ES the percentage of monosyllabic words [

17]. As with LIX, higher WSF1 values indicate greater complexity, with scores between 7 and 10 representing well understandable content and values above 12 considered difficult to very difficult.

2.6. Statistical Analysis

We first conducted a descriptive evaluation of chatbot–patient conversations.

Readability of chatbot outputs was quantified using FRE, LIX and WSF1. To explore differences in readability across conversation topics (disease, procedure, theme), we applied Kruskal–Wallis rank sum tests. This non-parametric approach was selected due to the non-normal distribution of readability scores and unequal group sizes. Results are reported with corresponding effect measures, 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs) and p-values.

Perceived readability was assessed using four Likert-scale items. Although single items are ordinal, aggregation into a composite score with good internal consistency (Cronbach’s α = 0.75) allows treatment as an interval-scaled variable. Also, an exploratory factor analysis (EFA) was conducted to further examine the dimensionality of the scale.

Correlations between objective readability indices and perceived readability were estimated using Spearman’s rank correlation coefficients. These analyses were defined a priori, and results are reported with ρ-coefficient, 95% CIs and p-values.

Lastly, we explored the potential influence of patient characteristics on perceived readability. A multiple linear regression model was fitted including the composite perceived readability score as the dependent variable. Age and educational level were included as predictors, as they were considered potentially influential on health literacy. Regression results are reported with coefficients (β), 95% CIs and p-values.

All statistical analyses were performed using RStudio (Version 2025.05.0 + 496, Posit Software, PBC, Boston, MA, USA). A significance level of 0.05 was applied throughout. Only the main results are reported within the manuscript, for a detailed view of the comprehensive results we refer to the

Supplementary Materials.

3. Results

3.1. Conversation Content Analysis

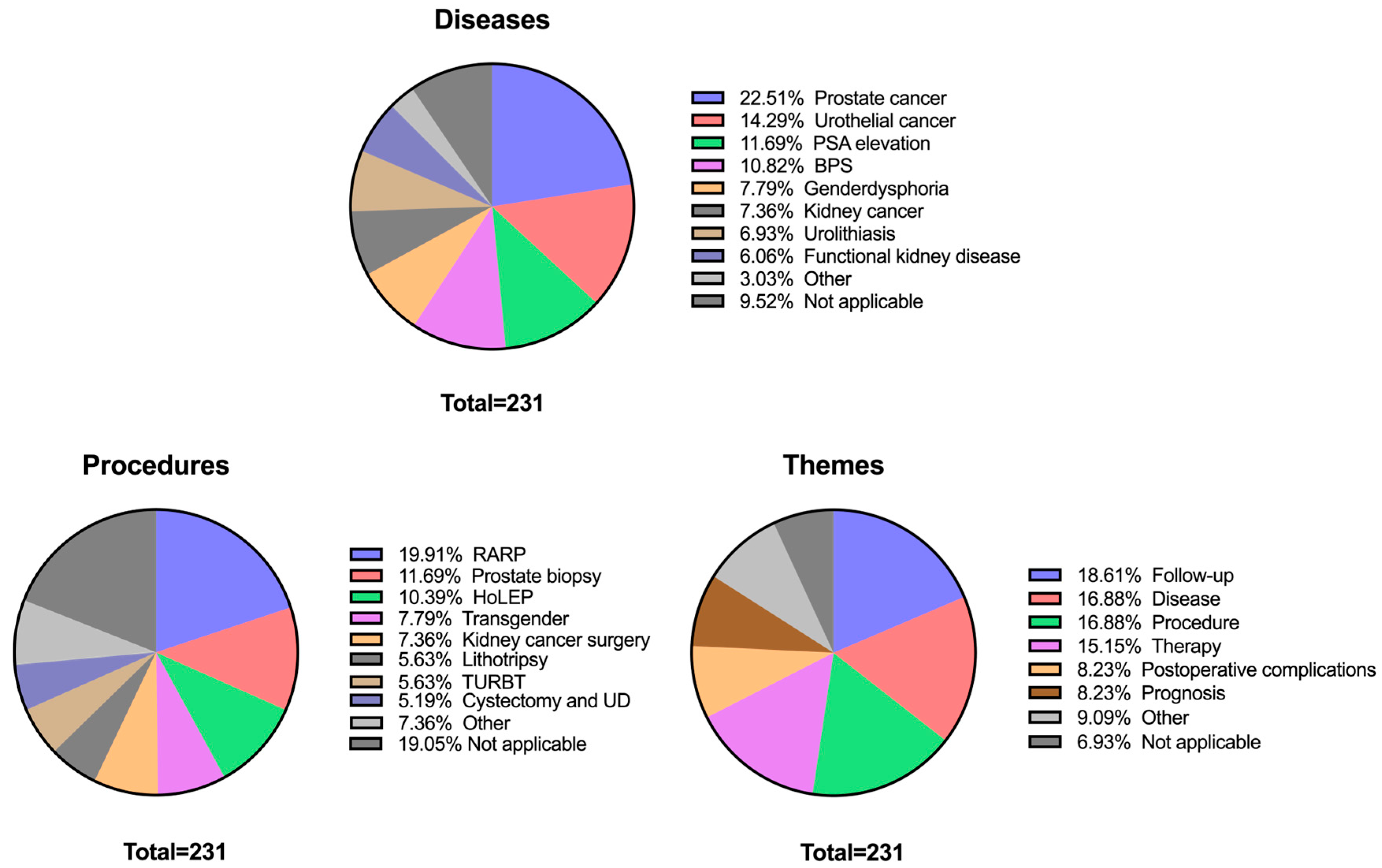

To contextualize patient–chatbot interactions beyond readability metrics, we performed a qualitative analysis of the conversation content. A total of 231 chatbot–patient conversations were analyzed and categorized according to the discussed topics: disease, procedure, and overarching theme.

Regarding disease-related topics, the most frequently discussed conditions included prostate cancer (52/231; 22.5%), urothelial cancer (33/231; 14.3%), and suspicious PSA elevation (27/231; 11.7%). Procedural discussions were led by robotic-assisted radical prostatectomy (RARP, 46/231; 19.9%), prostate biopsy (27/231; 11.7%), and Holmium Laser Enucleation of the Prostate (HoLEP, 24/231; 10.4%). Conversations also covered a diverse range of interventions, including kidney cancer surgery (17/231; 7.4%), lithotripsy procedures (13/231; 5.6%) and radical cystectomy with urinary diversion (12/231; 5.2%). However, 44 of 231 (19.1%) transcripts were not applicable to a specific procedure, because they were either focused on a specific disease or on overarching medical themes (e.g., follow-up, prognosis).

When categorized into overarching themes, questions about follow-up (43/231; 18.6%), disease biology (39/231; 16.9%) and procedural steps (39/231; 16.9%) dominated. General therapy related questions constituted 35 of 231 (15.2%) of conversations, while postoperative complications (19/231; 8.2%) and prognostic concerns (19/231; 8.2%) were also recurrent themes. A comprehensive overview of discussed topics is provided in

Figure 1.

3.2. Conversation Readability Analysis

To complement the qualitative assessment of conversational topics, we next examined quantitative transcript metrics, including word and sentence counts as well as readability indices (FRE, LIX, WSF). This analysis was aimed at evaluating both pooled and grouped (by topics) readability of chatbot outputs.

Across all transcripts, the average language was classified as difficult according to the FRE (43.07; SD 9.06), while LIX indicated a difficult level (52.82; SD 6.17), and WSF corresponded to an upper-secondary reading level (11.20; SD 1.63). On average, responses contained 175 words (SD 54) distributed across approximately 15 sentences (mean 14.74; SD 6.52).

Readability indices (FRE, LIX, WSF) did not differ meaningfully with respect to disease, procedure or overarching theme discussed (all

p ≥ 0.5; all ε

2 small with 95% CIs spanning near zero). A single nominally significant finding (procedure–LIX,

p = 0.031, ε

2 = 0.05) would not remain significant after correcting for multiple comparisons. Word and sentence counts differed across thematic categories (words:

p = 0.007; sentences:

p = 0.004), yet effect sizes are not tabulated, since exploratory analyses revealed no meaningful or robust group differences between topic categories and readability indices. Detailed results of readability indices stratified by topic categories are provided in

Supplementary Tables S3–S5.

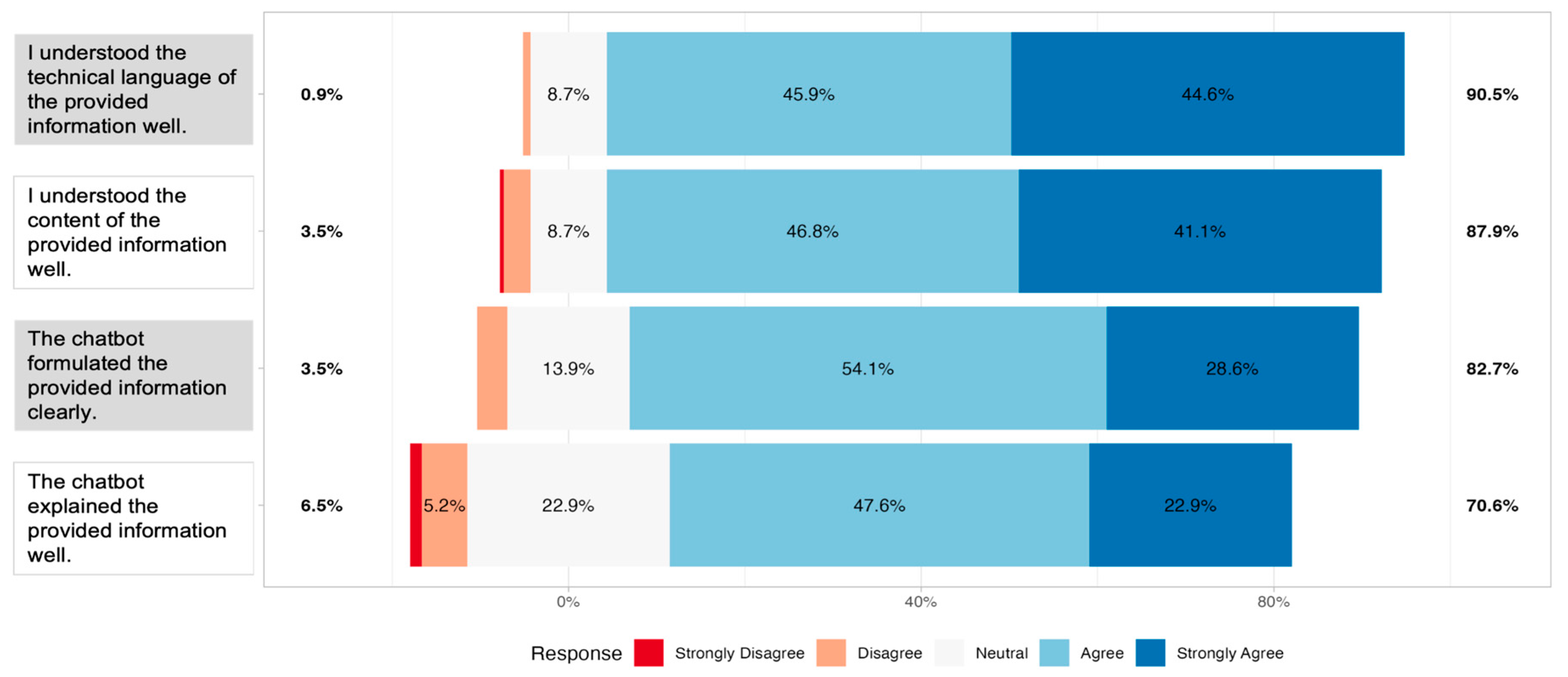

3.3. Perceived Readability

Next, we examined patients’ subjective evaluations of chatbot output readability. Survey responses showed that most participants perceived the outputs as readable across all four items. For the statement on understanding the technical language of the provided information, 90.5% of respondents agreed or strongly agreed, with only 1% reporting strong disagreement. Similarly, 87.9% agreed or strongly agreed to have “understood the content of the provided information well”. The statement “the chatbot formulated the provided information clearly” was endorsed positively by 82.7% of participants. The lowest level of agreement was observed for the item “The chatbot explained the provided information well”; however, 70.6% still agreed or strongly agreed (

Figure 2).

Together, these findings demonstrate that, despite objectively difficult readability levels, patients largely perceived the responses of the chatbot as clear, understandable and explanations as appropriate.

An exploratory factor analysis (maximum likelihood extraction, oblimin rotation) was conducted on the four readability items. Internal consistency was acceptable (Cronbach’s α = 0.75). A two-factor solution accounted for 77% of the variance. Factor 1 (ML1) was defined by the H-items, with loadings of 0.80 (H1) and 1.00 (H2). Factor 2 (ML2) was defined by the E-items, with loadings of 1.00 (E2) and 0.60 (E4). The two factors were moderately correlated (r = 0.30).

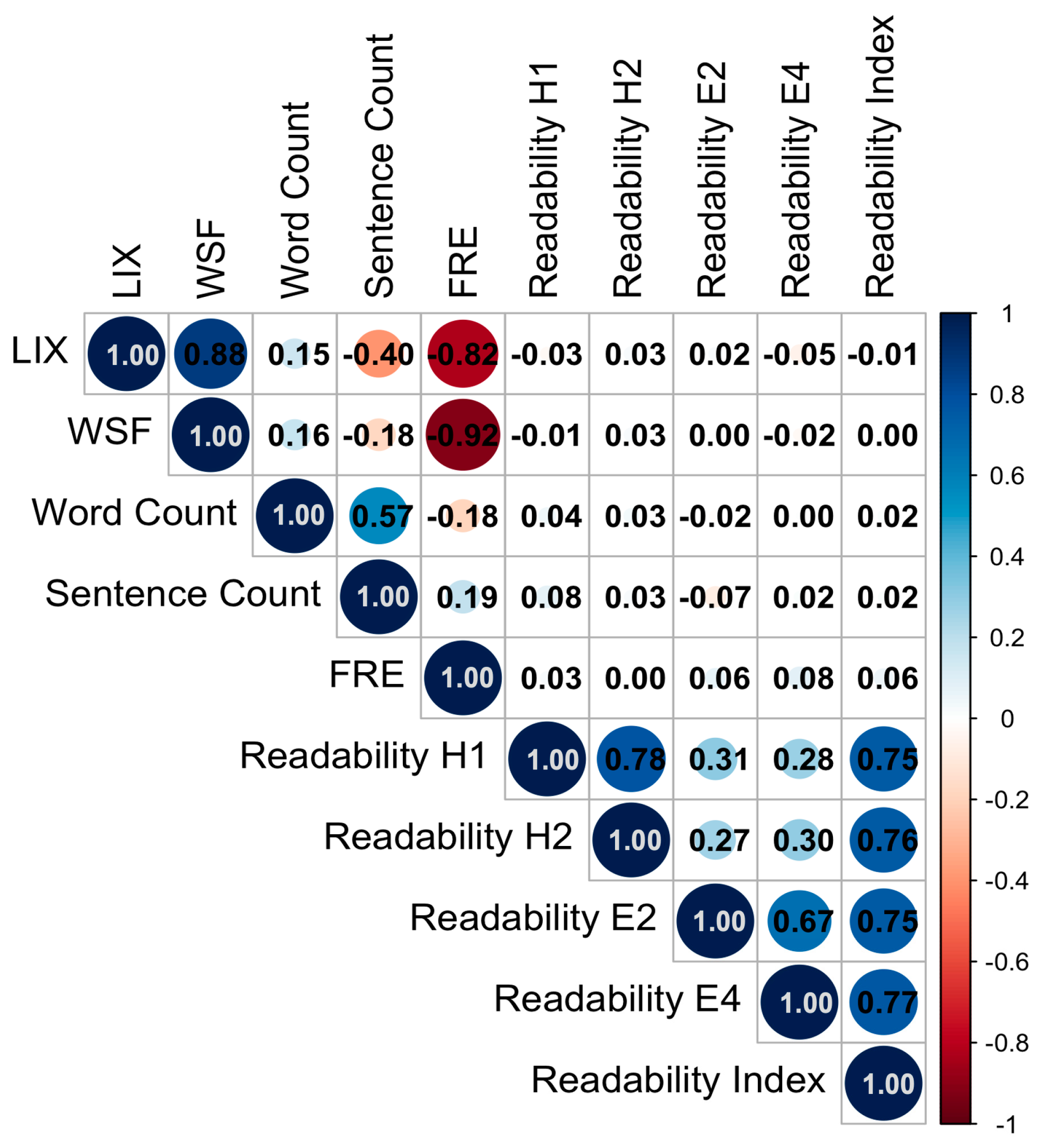

3.4. Correlation Analysis

Strong positive correlations were observed between the LIX and WSF readability indices (ρ = 0.88; p < 0.001; 95%CI = 0.82–0.90), while both showed strong negative correlations with the FRE index (FRE vs. LIX: ρ = −0.82; p < 0.001; 95%CI = −0.85–0.74; FRE vs. WSF: ρ = −0.92; p < 0.001; 95%CI = −0.92−0.87), reflecting the inverse scaling of these measures. Word count correlated moderately with the number of sentences (ρ = 0.57; p < 0.001; 95%CI = 0.46–0.64), but only weakly with readability metrics. In total, the German-specific indices LIX and WSF correlated strongly with FRE, indicating internal validity of the applied metrics.

Interestingly, no notable correlations were observed between objective readability indices (FRE, LIX, WSF) and perceived readability items directly (see

Figure 3).

3.5. Demographic

In total 230 of 231 participants provided demographic data. Participants were recruited primarily during pre-admission consultations for upcoming urological interventions, potentially yielding a sample that was more digitally engaged than typical outpatient populations. The mean age was 60.97 years (SD 15.91), most participants were senior or elderly (190/230, 83%). Over the past year, the majority reported frequent healthcare contact: 65% (148/229) visited a physician more than five times and 35% (80/229) reported 1–5 visits. Most respondents had used the internet for medical information (195/229, 85%), evenly distributed across age strata. More than half used the internet daily for medical questions (119/229, 52%), while 33% used it weekly and 15% monthly. Google was the predominant information source (181/214, 85%), followed by Wikipedia and official patient forums (each 8/214, 3.7%); other sources were rare. Prior use of an LLM for medical questions was reported by only 9.0% (20/222), with a clear age gradient (young adults 15%, adults 25%, seniors 8.5%, elderly 5.4%; p = 0.029). Among LLM users, ChatGPT was most frequently named (19/22, 86%). The sample was predominantly male (167/226, 74%), representing the distribution of a real-world urological cohort. Educational attainment was reported by 193 of the 231 participants. Among these, 26 patients (13%) were classified as ISCED level 1, 68 (35%) as ISCED level 2, 31 (16%) as ISCED level 3 and 68 (35%) as ISCED level 4. Educational attainment was unknown for 37 patients (16%). Patients were distributed ranging from vocational training to higher academic degrees.

Furthermore, the potential influence of demographic factors (age and educational level) on perceived readability outcomes was explored. Neither age nor educational level showed statistically significant associations with perceived readability outcomes (all

p > 0.15). The effect estimates were small, and confidence intervals crossed zero throughout, indicating no meaningful relationship. Thus, perceived readability appeared independent of participants’ age and educational attainment within the current evaluation. Tabulated results of the regression are displayed in

Supplementary Table S6.

4. Discussion

The present study aimed to evaluate how patients experience the readability of chatbot-generated health information in urological care. By analyzing 231 transcripts from a speech-mediated GPT-4 chatbot, we assessed both: objective readability using established indices, and patients’ perceived readability through reported outcomes. We found that although chatbot responses were objectively written at a higher-than-recommended level, patients generally perceived them as understandable.

This work extends prior research which primarily surveyed patient perceptions of LLMs. Earlier analyses focused on user-reported outcomes such as informational quality, user-friendliness, empathy, self-disclosure and trust in medical decision-making when comparing chatbots, search engines, and physicians [

9,

14,

15]. In contrast, the present analysis examines the conversations themselves, enabling the first direct comparison between objective readability metrics and patients’ subjective evaluations.

Notably, participants rated the information as highly clear and understandable despite the objectively complex reading levels. Perceived readability did not vary with age or education, and there was no association between topic complexity and subjective clarity. Several factors may explain this phenomenon. First, participants interacted with the chatbot through speech while concurrently reading the transcribed answers. This multimodal information intake may have enhanced comprehension by engaging multiple sensory channels and allowing patients to process content at their own pace. A meta-analysis of 30 studies found an overall benefit of reading while listening versus reading only, supporting the plausibility of our multimodal explanation [

19]. Second, the conversational format permitted patients to steer discussions toward personally relevant questions. Such dynamic, interest-driven engagement likely increased motivation and cognitive focus, making lengthy explanations easier to follow. Third, the answers of the chatbot were verbose. Although verbosity inflates readability scores, elaboration may provide additional explanations. Together, we showed that there is a dissonance between readability indices and reported readability suggesting that readability indices may not fully capture the cognitive processes involved in interactive, speech-based learning.

A further aspect to consider is the potential influence of the Dunning–Kruger effect on our subjective readability ratings. The Dunning–Kruger effect is a cognitive bias whereby individuals with limited knowledge or skill overestimate their own competence [

20]. In the context of health literacy, research has shown that respondents with objectively low health literacy reported as much or more confidence in their health knowledge than those with higher literacy, despite engaging in more problematic health behaviors and failing to recognize their informational deficits [

21]. Moreover, studies highlight that health literacy is generally low in the population and that people are unrealistically optimistic about their health risks [

22]. This effect appears to be particularly pronounced among male individuals [

23], who constitute approximately two-thirds of the urological patient population. Applied to our cohort, these findings raise the possibility that some participants, particularly those with lower health literacy or who are male, may have overestimated their understanding of the explanation of the chatbot.

Additionally, response biases such as social desirability may further inflate perceived readability. Social desirability bias refers to a pervasive response bias in which individuals tailor their answers to align with perceived social norms or to present themselves in a favorable light. Acquiescent response sets have also been shown to upwardly bias satisfaction scores when items are positively worded [

24]. Experimental evidence from patient satisfaction surveys demonstrates that positively framed statements yield markedly higher satisfaction than the same items presented negatively [

25], while demographic factors like older age and lower education are associated with higher satisfaction regardless of content [

26]. These observations indicate that subjective readability ratings may partly reflect response tendencies and social expectations rather than genuine comprehension.

LLM outputs were objectively demanding, yet showed no significant differences in readability across diseases, procedures, or overarching themes. Procedure-related questions ranged from simple interventions such as prostate biopsy to complex procedures like radical cystectomy, yet objective readability metrics remained uniformly high across categories. The absence of statistically significant differences in FRE, LIX or WSF between simple and complex topics suggests that the model produces text at a relatively stable level of linguistic complexity. That level consistently exceeds recommended sixth-grade thresholds, mirroring findings in other specialties where unmodified ChatGPT outputs for otosclerosis, chemotherapy cardiotoxicity or prostate cancer information required college-level comprehension [

11,

27,

28]. In a study by Thia et al., chatbot-generated urological explanations demonstrated poor Flesch–Kincaid performance, but readability markedly improved once the prompt was adapted to generate content suitable for a 16-year-old audience [

29]. This finding aligns with other studies demonstrating that targeted prompting strategies enabled GPT-4 to generate lay summaries and rewrite complex materials into simpler formats without compromising accuracy. This underscores that employing alternative prompting strategies, such as adding more descriptive context or explicitly targeting lower reading levels, may be crucial for optimizing readability outcomes [

2,

12]. Such approaches are particularly relevant for patient-facing oncology materials and conversational agents, where clarity and accessibility are critical for informed decision-making [

11,

30].

This study has limitations. Most importantly, only objective readability measures and participants’ perceived subjective readability were assessed. The study design did not account for specific knowledge retention. Because conversations were open-ended and covered diverse topics, it was not feasible to develop a standardized knowledge test. Our analysis is limited to GPT-4, acknowledging that different LLMs might vary in complexity and output readability. Nevertheless, ChatGPT powered by GPT-4 is among the most widely adopted proprietary models in clinical and public use. Additionally, there is a chance for selection bias by including only patients who agreed to participate. Individuals who declined may systematically differ in their attitudes toward AI due to higher levels of skepticism or rejection. In the present study, this potential selection bias could inflate perceived readability [

31]. Another limitation is that participants were recruited during their pre-admission consultations for planned urological interventions. As many participants presented with urooncological conditions, many had recently received a diagnosis and may have used the Internet more intensively. This selection may have contributed to the high perceived readability observed in our study.

Going forward, longitudinal studies incorporating objective knowledge tests, cross-model comparisons, and more diverse participant groups will be essential to fully understand the effect of AI chatbots in patient education.