Supporting Employment After Cancer: A Mixed-Methods Evaluation of a Vocational Integration Programme for Childhood, Adolescent, and Young Adult Cancer Survivors

Abstract

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

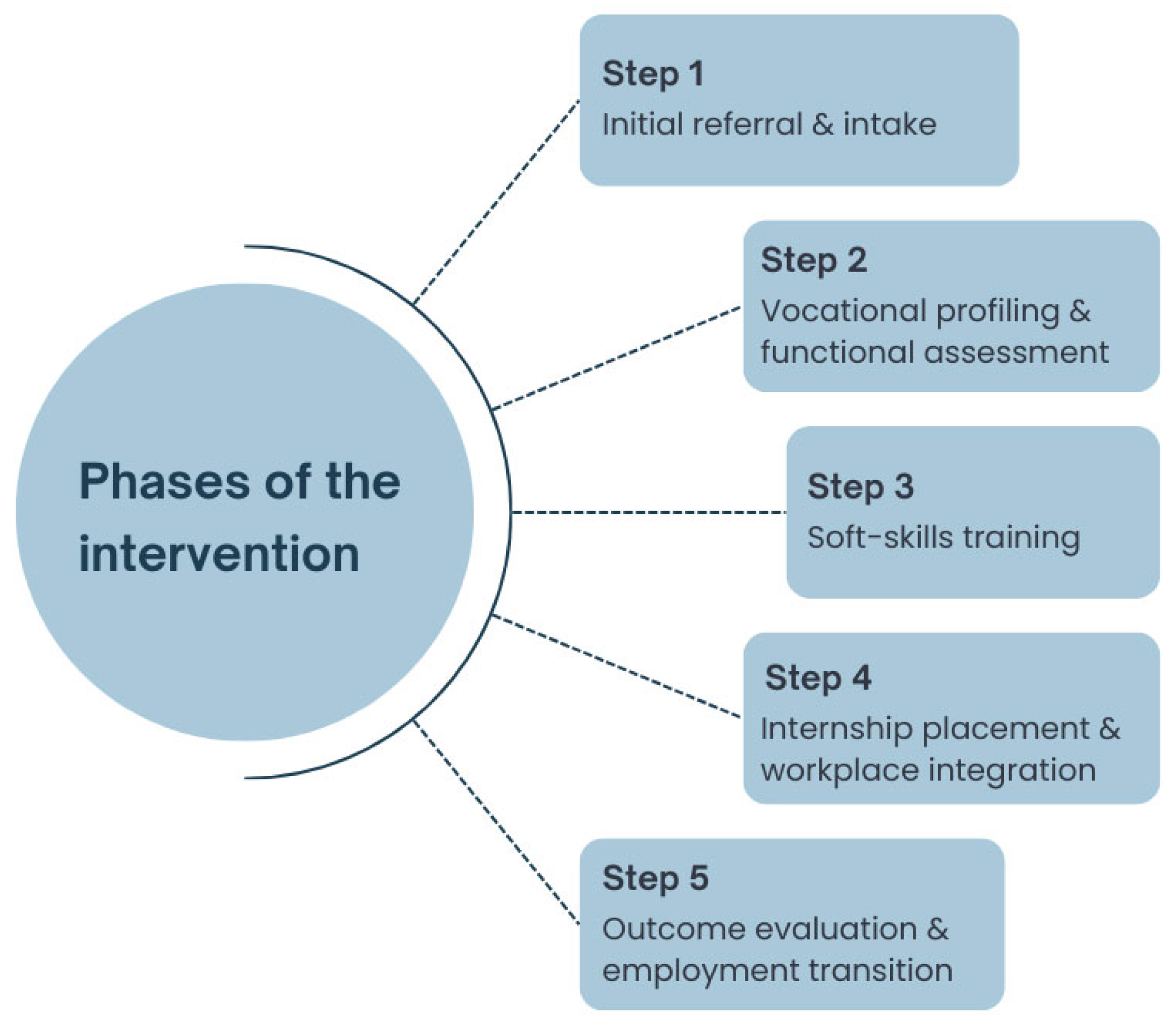

2.1. The Intervention

- Initial referral and Intake: The beneficiary is connected with the multidisciplinary team and referred to the designated Patchanka project manager.

- Vocational profiling and functional assessment: An initial assessment phase is conducted, involving individualised vocational guidance, curriculum vitae development, functional and disability evaluations, and mapping of skills, interests, and employment-related barriers.

- Soft-skills training: A subset of beneficiaries engages in group sessions through theatrical techniques via the JobAct® Method, aimed at enhancing soft skills such as communication, emotional regulation, and workplace self-efficacy [37].

- Internship Placement and Workplace Integration: Patchanka employment specialists identify host companies compatible with the physical, cognitive, and professional profiles of participants. They provide structured support throughout workplace integration, including onboarding facilitation and interpersonal mediation. The internship is remunerated and fully funded by UGI. Participants proceed autonomously while retaining access to the project manager for case-specific support.

- Outcome Evaluation and Employment Transition: Upon completion of the internship, outcome evaluations are performed. These may lead to an extension of the placement, direct employment, or the initiation of new job-matching procedures.

2.2. The Mixed-Methods Follow-Up Study

3. Results

3.1. Quantitative Findings

3.2. Overall Experience and Three-Words Reflection Task

3.3. Results of the Thematic Analysis

- Theme 1: Motivations and initial expectations

- Theme 2: The impact of cancer on workability

- Theme 3: Accessibility and task adequacy

- Theme 4: The importance of building self-esteem and self-efficacy

- Theme 5: The value of vocational support

- Theme 6: The power of relationships: social support and workplace integration

- Theme 7: The double-edged impact of peer and family support

- Theme 8: Critical aspects and the role of social support

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CAYAC | Childhood, adolescent, and young adult cancers |

| CNS | Central nervous system |

| RTW | Return to work |

| SWTP | School and Work Transitions Program |

| HRQoL | Health related quality of life |

| SF-12 | 12-Item Short Form Health Survey |

| PCS | Physical Component Summary |

| MCS | Mental Component Summary |

| LE | Late effect |

| CLME | Chronic and late medical health events |

| CTCAE | National Cancer Institute’s Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events |

| CV | Curriculum Vitae |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

| ICF | International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health |

References

- Suh, E.; Stratton, K.L. Late mortality and chronic health conditions in long-term survivors of early-adolescent and young adult cancers: A retrospective cohort analysis from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. Lancet Oncol. 2020, 21, 421–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Kalsbeek, R.J.; van der Pal, H.J.H. European PanCareFollowUp Recommendations for surveillance of late effects of childhood, adolescent, and young adult cancer. Eur. J. Cancer 2021, 154, 316–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Braun, I.; Friedrich, M. Changes, challenges and support in work, education and finances of adolescent and young adult (AYA) cancer survivors: A qualitative study. Eur. J. Oncol. Nurs. Off. J. Eur. Oncol. Nurs. Soc. 2023, 64, 102329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Winzig, J.; Inhestern, L. And what about today? Burden and support needs of adolescent childhood cancer survivors in long-term follow-up care—A qualitative content analysis. Child Care Health Dev. 2024, 50, e13207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudolf von Rohr, L.; Battanta, N. The Requirements for Setting Up a Dedicated Structure for Adolescents and Young Adults with Cancer—A Systematic Review. Curr. Oncol. 2025, 32, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egger-Heidrich, K.; Wolters, F. Long-term surveillance recommendations for young adult cancer survivors. Cancer Treat. Rev. 2025, 139, 102992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michel, G.; Mulder, R.L. Evidence-based recommendations for the organization of long-term follow-up care for childhood and adolescent cancer survivors: A report from the PanCareSurFup Guidelines Working Group. J. Cancer Surviv. Res. Pract. 2019, 13, 759–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buehlmann, L.; Otth, M. Longitudinal needs and cancer knowledge in Swiss childhood cancer survivors transitioning from pediatric to adult follow-up care: Results from the ACCS project. Discov. Oncol. 2024, 15, 450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hudson, M.M.; Ehrhardt, M.J. Approach for Classification and Severity Grading of Long-term and Late-Onset Health Events among Childhood Cancer Survivors in the St. Jude Lifetime Cohort. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 2017, 26, 666–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeVine, A.; Landier, W. The Children’s Oncology Group Long-Term Follow-Up Guidelines for Survivors of Childhood, Adolescent, and Young Adult Cancers: A Review. JAMA Oncol. 2025, 11, 544–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lown, E.A.; Phillips, F. Psychosocial Follow-Up in Survivorship as a Standard of Care in Pediatric Oncology. Pediatr. Blood Cancer 2015, 62 (Suppl. S5), S514–S584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Demoor-Goldschmidt, C.; Porro, B. Editorial: Young adults or adults who are survivors of childhood cancer: Psychosocial side effects, education, and employment. Front. Psychol. 2024, 15, 1510822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maas, A.; Maurice-Stam, H.; Feijen, E.A.M.; Teepen, J.C.; Delden, A.M.v.d.A.; Streefkerk, N.; Broeder, E.v.D.; Tissing, W.J.E.; Loonen, J.J.; van der Pal, H.J.H.; et al. Risk and Protective Factors of Psychosocial Functioning in Survivors of Childhood Cancer: Results of the DCCSS-LATER Study. Psycho-Oncology 2024, 33, e9313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miyagishima, K.; Ichie, K. The process of becoming independent while balancing health management and social life in adolescent and young adult childhood cancer survivors. Jpn. J. Nurs. Sci. 2023, 20, e12527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altherr, A.; Bolliger, C. Education, Employment, and Financial Outcomes in Adolescent and Young Adult Cancer Survivors—A Systematic Review. Curr. Oncol. 2023, 30, 8720–8762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirchhoff, A.C.; Leisenring, W. Unemployment Among Adult Survivors of Childhood Cancer. Med Care 2010, 48, 1015–1025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunnes, M.W.; Lie, R.T. Economic independence in survivors of cancer diagnosed at a young age: A Norwegian national cohort study. Cancer 2016, 122, 3873–3882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frederiksen, L.E.; Pedersen, C. Employment status and occupational positions of childhood cancer survivors from Denmark, Finland and Sweden: A Nordic register-based cohort study from the SALiCCS research programme. Lancet Reg. Health Eur. 2021, 12, 100258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dionisi-Vici, M.; Godono, A. Work Placement and Job Satisfaction in Long-Term Childhood Cancer Survivors: The Impact of Late Effects. Cancers 2022, 14, 3984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godono, A.; Felicetti, F. Employment among Childhood Cancer Survivors: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Cancers 2022, 14, 4586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devine, K.A.; Christen, S. Recommendations for the surveillance of education and employment outcomes in survivors of childhood, adolescent, and young adult cancer: A report from the International Late Effects of Childhood Cancer Guideline Harmonization Group. Cancer 2022, 128, 2405–2419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dumas, A.; Berger, C. Educational and occupational outcomes of childhood cancer survivors 30 years after diagnosis: A French cohort study. Br. J. Cancer 2016, 114, 1060–1068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Otth, M.; Michel, G. On Behalf Of The Swiss Pediatric Oncology Group Spog. Educational Attainment and Employment Outcome of Survivors of Pediatric CNS Tumors in Switzerland—A Report from the Swiss Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. Children 2022, 9, 411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- L’Hotta, A.J.; Randolph, S.B. Clinical practice guideline and expert consensus recommendations for rehabilitation among children with cancer: A systematic review. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2023, 73, 524–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhatt, N.S.; Goodman, P. Chronic Health Conditions and Longitudinal Employment in Survivors of Childhood Cancer. JAMA Netw. Open 2024, 7, e2410731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Signorelli, C.; Hart, N.H.; Mullen, L.; Nekhlyudov, L.; Travado, L.; Lam, W.W.T.; Henry, M.; Dégi, C.L.; Haywood, D.; Jefford, M. Aligning the World Health Organization’s (WHO) package of interventions for rehabilitation for cancer with the mission of the International Psycho-Oncology Society’s: Promoting psychosocial care for all people affected by cancer. J. Psychosoc. Oncol. Res. Pract. 2024, 6, 144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dionisi-Vici, M.; Giacoppo, I. Childhood, adolescent and young adult cancer survivors: Health promotion and wellbeing interventions. Curr. Opin. Epidemiol. Public Health 2025, 4, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Boer, A.G.; Taskila, T.K.; Tamminga, S.J.; Feuerstein, M.; Frings-Dresen, M.H.W.; Verbeek, J.H. Interventions to enhance return-to-work for cancer patients. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2011, 16, 1343. [Google Scholar]

- Arpaci, T.; Altay, N. Psychosocial interventions for childhood cancer survivors: Systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized control trials. Eur. J. Oncol. Nurs. Off. J. Eur. Oncol. Nurs. Soc. 2024, 69, 102541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peikert, M.L.; Inhestern, L. Psychosocial interventions for rehabilitation and reintegration into daily life of pediatric cancer survivors and their families: A systematic review. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0196151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradford, N.K.; Chan, R.J. Health promotion and psychological interventions for adolescent and young adult cancer survivors: A systematic literature review. Cancer Treat Rev. 2017, 55, 57–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tamminga, S.J.; de Boer, A.G. Return-to-work interventions integrated into cancer care: A systematic review. Occup. Environ. Med. 2010, 67, 639–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zegers, A.D.; Coenen, P. Tailoring work participation support for cancer survivors using the stages of change: Perspectives of (health care) professionals and survivors. J. Cancer Surviv. Res. Pract. 2023, 17, 706–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pole, J.D.; Williams, B. Measuring what gets done: Using goal attainment scaling in a vocational counseling program for survivors of childhood cancer. Cancer Med. 2023, 12, 8676–8689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UGI. Unione Genitori Italiani Contro il Tumore dei Bambini. Available online: https://ugi-torino.it/ (accessed on 20 August 2025).

- Patchanka. Available online: https://cooperativapatchanka.org/ (accessed on 20 August 2025).

- JobACT. Available online: https://www.projektfabrik.org/index.php/about-jobact.html (accessed on 18 July 2025).

- Hammarberg, K.; Kirkman, M. Qualitative research methods: When to use them and how to judge them. Hum. Reprod. 2016, 31, 498–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ware, J., Jr.; Kosinski, M. A 12-Item Short-Form Health Survey: Construction of scales and preliminary tests of reliability and validity. Med. Care 1996, 34, 220–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kallio, H.; Pietilä, A.M. Systematic methodological review: Developing a framework for a qualitative semi-structured interview guide. J. Adv. Nurs. 2016, 72, 2954–2965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Reflecting on reflexive thematic analysis. Qual. Res. Sport Exerc. Health 2019, 11, 589–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brignardello, E.; Felicetti, F. Endocrine health conditions in adult survivors of childhood cancer: The need for specialized adult-focused follow-up clinics. Eur. J. Endocrinol. 2013, 168, 465–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zucchetti, G.; Ciappina, S. The Creation of a Transition Protocol Survey for Childhood, Adolescent, and Young Adult Cancer Survivors in Transition from Pediatric to Adult Health Care in Italy. J. Adolesc. Young Adult Oncol. 2022, 11, 202–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Legge 104/1992; Legge-quadro per l’assistenza, l’integrazione sociale e i diritti delle persone handicappate. Gazzetta Ufficiale della Repubblica Italiana: Rome, Italy, 1992. Available online: https://www.gazzettaufficiale.it/eli/id/1992/02/17/092G0108/s (accessed on 18 July 2025).

- Legge 68/1999; Norme per il diritto al lavoro dei disabili. Gazzetta Ufficiale della Repubblica Italiana: Rome, Italy, 1999. Available online: https://www.gazzettaufficiale.it/eli/id/1999/03/23/099G0123/s (accessed on 18 July 2025).

- Ministero della Salute. Invalidità civile e riconoscimento dello stato di handicap. Available online: https://www.salute.gov.it/new/it/faq/faq-esenzioni-invalidita/?utm_source=chatgpt.com (accessed on 18 July 2025).

- World Health Organization. International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF). 2001. Available online: https://www.who.int/standards/classifications/international-classification-of-functioning-disability-and-health (accessed on 18 July 2025).

- Dionisi-Vici, M.; Felicetti, F. The impact of infertility and physical late effects on psycho-social well-being of long-term childhood cancer survivors: A cross-sectional study. EJC Paediatr. Oncol. 2023, 2, 100025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ketterl, T.G.; Syrjala, K.L. Lasting effects of cancer and its treatment on employment and finances in adolescent and young adult cancer survivors. Cancer 2019, 125, 1908–1917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brock, H.; Friedrich, M. Work ability and cognitive impairments in young adult cancer patients: Associated factors and changes over time-results from the AYA-Leipzig study. J. Cancer Surviv. Res. Pract. 2022, 16, 771–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goto, S.; Itani, Y. Impact of work-related changes on health related quality of life in adolescent and young adult cancer survivors. J. Psychosoc. Oncol. Res. Pract. 2024, 6, 126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, J.; Shao, L. The mediating role of self-efficacy in the relationship between social support and work withdrawal behavior: A cross-sectional study among young lung cancer survivors. Asia Pac. J. Oncol. Nurs. 2023, 10, 100207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| No. | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||

| Female | 6 | 46.2 |

| Male | 7 | 53.8 |

| Age at diagnosis | ||

| 0–4 | 2 | 15.4 |

| 5–9 | 0 | 0.0 |

| 10–14 | 6 | 46.2 |

| ≥15 | 5 | 38.4 |

| Age at the interview | ||

| 20–24 | 5 | 38.4 |

| 25–29 | 6 | 46.2 |

| 30–34 | 1 | 7.7 |

| ≥35 | 1 | 7.7 |

| Off-therapy | ||

| <2000 | 1 | 7.7 |

| 2000–2009 | 2 | 15.4 |

| 2010–2014 | 4 | 30.8 |

| ≥2015 | 6 | 46.2 |

| Education | ||

| Middle school | 4 | 30.8 |

| High school | 8 | 61.5 |

| University | 1 | 7.7 |

| Diagnosis | ||

| Acute Leukaemia (Myeloid or lymphoblastic) | 5 | 38.4 |

| CNS Tumours | 4 | 30.8 |

| Others * | 4 | 30.8 |

| Chemotherapy | 12 | 92.3 |

| Radiotherapy | 6 | 46.2 |

| Neurosurgery | 4 | 30.8 |

| Hematopoietic stem cell transplantation | 2 | 15.4 |

| Disease Relapse | 1 | 7.7 |

| Late effects ** | ||

| Patients with ≥ 1 LE | 12 | 92.3 |

| Grade 1 | 7 | 17.5 |

| Grade 2 | 25 | 62.5 |

| Grade 3 | 8 | 20.0 |

| Second Neoplasm | 2 | 15.4 |

| M | SD | Range | |

|---|---|---|---|

| SF-12 | |||

| PCS | 45.2 | 9.1 | 33.7–64.3 |

| MCS | 43.5 | 11.2 | 26.3–63.1 |

| 0–10 rating | 8.3 | 2.0 | 5.0–10.0 |

| Codes | Beneficial | Satisfying | Relational | Educational | Stimulating | Limiting | Demanding |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Categories | rewarding | stimulating | challenging | ||||

| Theme 1: Motivations and Expectations | |

| Category 1.1: Desire for autonomy and financial independence | Hoping to get hired and have a salary. (P1) The desire to leave my home and feel more independent (P2; P9)—to be useful to others. (P2) I wanted to be independent, to stop asking my parents for money. I wanted to work! (P3) |

| Category 1.2: Desire for employment and personal development | I didn’t have expectations about what I’d like to do, but they formed over time through these experiences. (P4) I made mistakes. Since it was my first real job, I didn’t behave at my best. (P6) I didn’t even know where to start looking for a job. (P6; P8) I was willing to do anything, within my limits. (P8) The desire to work, grow, learn new things, and to feel normal in a way. After being in the hospital context, doing heavy jobs isn’t ideal. (P12) |

| Theme 2: The impact of cancer on workability | |

| Category 2.1: Physical constraints on occupational choice | My career goals have changed a little bit. The doctor told me that certain jobs would be too demanding for me and my health, and suggested that office work would be better for me. (P2) I realized that the problems I had in the past are still affecting me: fatigue and physical health issues. I’ve always avoided and denied being limited by my illness, but then I realized I do have limitations. I’m cancer free, but I get tired very easily. (P3) I would have loved to attend a sports-focused high school, since I was really passionate about sports. Unfortunately, due to my physical conditions, I was told it wasn’t possible. (P5) I do have eye-related issues, and I think that it would affect any job. (P13) |

| Category 2.2: Employment loss due to physical impairments | Some jobs are hard if you are not healthy. I had to stop [a previous job] because of severe shoulder pain. They needed someone who could function every day. (P3) I had to stop [my internship] due to a surgery that kept me in the hospital for a month. After that they weren’t able to keep me on. (P5) |

| Category 2.3: Impact on emotional well-being | I always have anxiety about feeling unwell at work. (P3) A lot of us have our own struggles. (P7) Most things I’ve faced aren’t comparable to what I went through in the hospital—nothing was harder than that! (P12) |

| Theme 3: Accessibility and task adequacy | |

| Category 3.1: Previous work-related challenges | I found a job on my own as a construction worker for about a year, but it was very hard. Even though I earned money, I chose to quit because I wasn’t well. (P10) The shift working hours can be tough for someone with a medical past, even if it’s not physically demanding. I’d already worked in physically demanding jobs before, so I wanted to change the environment a bit. (P12) |

| Category 3.2: Successful alignment with workability | They did their best to arrange the internship. (P3) They had informed me that I’d be working at the register due to my physical limitations. Occasionally, I took on other tasks, but nothing too physically demanding. (P5) [The intervention] helped me find something more stable [work]. (P7). Now I sit at a desk and don’t have to exert myself physically. (P13) |

| Theme 4: The importance of building self-esteem and self-efficacy | |

| Category 4.1: Increasing self-esteem | I suffer a lot from anxiety—especially when I’m around people, or when I have to talk to many people at once, or juggle a lot of tasks. This job helped me manage that. (P5) Before, I saw everything negatively—like I wasn’t good at anything. Now, even if a [job] interview doesn’t go well, I treat it as experience and not as failure. (P8) [The intervention] was short, so I’m not sure about a full self-esteem shift, but it gave me more confidence to try things on my own. (P9) I didn’t imagine myself wearing a shirt every day. It’s a formal environment. My mindset has really changed. (P12) |

| Category 4.2: Enhancing self-efficacy | Now, that I’ve had a serious experience, I understand how the work world operates—how to behave with colleagues, how to collaborate with them and with managers. (P2) Now, I see my future in a more positive and autonomous way. I am definitely more autonomous in terms of work tasks. (P4) I’ve built up my skills, I feel confident and independent. I no longer need assistance. I developed skills, learning how to adapt different situations. (P5) I’ve changed for the better. Now I enjoy working, I’m active, my days are fuller, and I have a daily routine. (P10) |

| Category 4.3: Occupational embeddedness | I am very happy because they asked me to stay. Now I also work night shifts. It’s more demanding and I have more responsibilities. (P5) My supervisor wants to offer me a one-year contract. (P6) Especially now that they’ve offered me a contract, I know that a company might actually want me. (P13) |

| Theme 5: The value of vocational support | |

| Category 5.1: Enhancing general job skills | The CV writing session was really helpful—mine needed a lot of work—and [the career coaches] helped me in improving it. (P7) It was my first time. They help you to understand and guide you in what you might want to do, your options, the pros and cons. They helped me think about other paths, other possibilities through my CV. (P12) I’d written a CV before, but something was missing, so they helped me to structure it better. (P13) |

| Category 5.2: Perceived impact of the intervention | The project helped by connecting me with the right people and finding options that suited me. (P8) The tasks of the internship were aligned with what we had discussed during the individual interview. During the second interview, I got the chance to do an internship—that made it feel more concrete. The project helped me narrow things down and find what to specialize in. (P9) |

| Category 5.3: Focus on personal growth | It was definitely a stimulating experience. It helped me work through the anxiety I feel when speaking in front of others, facing large audiences, and juggling several tasks simultaneously. (P5) |

| Theme 6: The power of relationships: social support and workplace integration | |

| Category 6.1: Growth through social interactions | Interacting with customers helped me break out of my shell. I used to be shy and awkward, but I really came to enjoy those interactions. Now, I’m much more confident in conversations with people. (P8) The most pleasant moment was when they trusted me enough to leave me in charge of the structure. Working with people and being in contact with them, it’s fulfilling. (P12) |

| Category 6.2: Sense of belonging and motivation | My tutor used to stop by the office every morning and say that even if there was nothing to sign, she wanted to see my smile—it made her day better. (P2) I got along even better with my last manager than the previous one. She really taught me a lot, and I became very patient. (P3) One colleague in particular still offers help—even now that I’m working night shifts, I know I can rely on her if anything comes up. (P5) I felt supported and comfortable whenever I needed help. I think that finding good people at work makes a huge difference. One of the girls from Patchanka advocated for me, and that helped get my contract extended. (P7) My tutor is very kind and helpful, but she lets me handle things independently, too. She gives me general guidance and says ‘Go ahead, and I’ll review it.’ (P13) |

| Category 6.3: Peer feedback and support | I also made friends during the project, and I still keep in touch with them. I met a girl who became my best friend. (P5) Also, group activities taught me a lot about myself. I picked up on things I hadn’t noticed before, especially through feedback from others and moments shared during group work. I became especially close with my tutor. I also learned tailoring from a colleague, and we’re still friends. (P8) |

| Theme 7: The double-edged impact of family support | |

| Category 7.1: Family support as a facilitator | [Family support] helped very much. They were happy because they saw I was happy, too. (P2) I used to complain a lot, and my family encouraged me to join. They were very supportive. (P8) My family supported me, both emotionally and practically, like giving me rides when they can. They supported and motivated me throughout. (P9) Yes, my family has always supported me in general and also encouraged me to continue with these projects. Even during the tough times, my mother gave me strength. From when I got sick until now, she’s always stayed close to me. (P11) |

| Category 7.2: Family support as a barrier | They weren’t against it, but when I wasn’t feeling well, they advised me to stop if I wasn’t okay. (P3) My mom always worries I might be too tired, so I try to reassure her. Previous jobs were short and poorly paid. My brother wasn’t thrilled, but for me it was nevertheless a way to get out of my home. (P7) |

| Theme 8: Critical aspects and the role of social support | |

| Category 8.1: Critical reflections | I thought it would be more helpful in finding a job. It was useful as a personal experience—but not professionally. (P11) |

| Category 8.2: Importance of social support at the workplace | There wasn’t a specific person explaining things, so I asked different people in the stores. (P1) What truly made a difference was having someone help me at the beginning to understand what I needed to do. (P2) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Dionisi-Vici, M.; Schneider-Kamp, A.; Giacoppo, I.; Godono, A.; Biasin, E.; Varetto, A.; Arvat, E.; Felicetti, F.; Zucchetti, G.; Fagioli, F. Supporting Employment After Cancer: A Mixed-Methods Evaluation of a Vocational Integration Programme for Childhood, Adolescent, and Young Adult Cancer Survivors. Curr. Oncol. 2025, 32, 564. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol32100564

Dionisi-Vici M, Schneider-Kamp A, Giacoppo I, Godono A, Biasin E, Varetto A, Arvat E, Felicetti F, Zucchetti G, Fagioli F. Supporting Employment After Cancer: A Mixed-Methods Evaluation of a Vocational Integration Programme for Childhood, Adolescent, and Young Adult Cancer Survivors. Current Oncology. 2025; 32(10):564. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol32100564

Chicago/Turabian StyleDionisi-Vici, Margherita, Anna Schneider-Kamp, Ilenia Giacoppo, Alessandro Godono, Eleonora Biasin, Antonella Varetto, Emanuela Arvat, Francesco Felicetti, Giulia Zucchetti, and Franca Fagioli. 2025. "Supporting Employment After Cancer: A Mixed-Methods Evaluation of a Vocational Integration Programme for Childhood, Adolescent, and Young Adult Cancer Survivors" Current Oncology 32, no. 10: 564. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol32100564

APA StyleDionisi-Vici, M., Schneider-Kamp, A., Giacoppo, I., Godono, A., Biasin, E., Varetto, A., Arvat, E., Felicetti, F., Zucchetti, G., & Fagioli, F. (2025). Supporting Employment After Cancer: A Mixed-Methods Evaluation of a Vocational Integration Programme for Childhood, Adolescent, and Young Adult Cancer Survivors. Current Oncology, 32(10), 564. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol32100564