Abstract

A Variant of Uncertain Significance (VUS) is a difference in the DNA sequence with uncertain consequences for gene function. A VUS in a hereditary cancer gene should not change medical care, yet some patients undergo medical procedures based on their VUS result, highlighting the unmet educational needs among patients and healthcare providers. To address this need, we developed, evaluated, and refined novel educational materials to explain that while VUS results do not change medical care, it remains important to share any personal or family history of cancer with family members given that their personal and family medical history can guide their cancer risk management. We began by reviewing the prior literature and transcripts from interviews with six individuals with a VUS result to identify content and design considerations to incorporate into educational materials. We then gathered feedback to improve materials via a focus group of multidisciplinary experts and multiple rounds of semi-structured interviews with individuals with a VUS result. Themes for how to improve content, visuals, and usefulness were used to refine the materials. In the final round of interviews with an additional 10 individuals with a VUS result, materials were described as relatable, useful, factual, and easy to navigate, and also increased their understanding of cancer gene VUS results.

1. Introduction

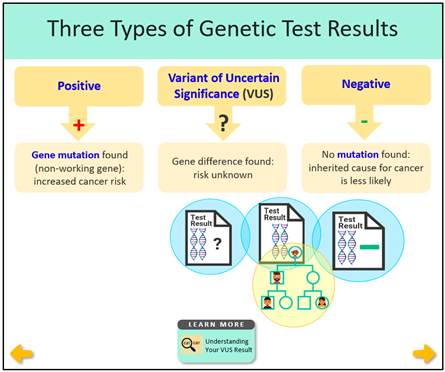

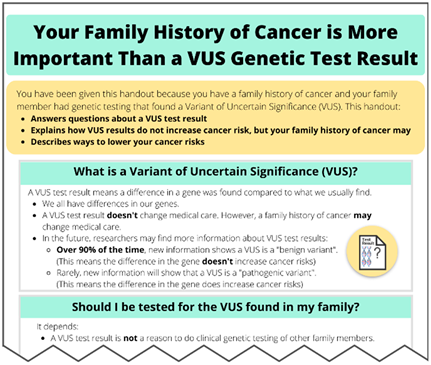

Approximately 5% of all colorectal cancers and 5 to 10% of breast cancers are caused by hereditary cancer predisposition syndromes that result from inheriting a germline pathogenic or likely pathogenic variant (GPV) in any one of several cancer risk genes [1,2]. Improvements in access to genetic testing and the ability to test for many genes simultaneously at a similar cost as testing for one or two genes have led to a higher number of patients identified as having a Variant of Uncertain Significance (VUS) result. Unlike GPVs, which are known to increase cancer risk, a VUS result has an uncertain impact on gene function and cancer risks. In a large study, 90% of VUS results were eventually downgraded to a negative result [3]. Based on several guidelines, including the American College of Medical Genetics (ACMG) and the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN), a VUS in a hereditary cancer gene should not change a patient’s medical management, and it is vital for patients to understand these guidelines to prevent unnecessary medical interventions [4,5].

While a VUS should not influence medical management, it remains important to discuss any personal and family history of cancer to guide cancer risk management among those with a VUS, similar to what is advised for those with negative genetic test results. For example, individuals who have a first-degree relative with certain types of cancer, such as breast or colorectal cancer, are at a higher risk for cancer themselves, and changes in cancer risk management, such as heightened cancer surveillance, may be warranted based on this familial risk [6,7,8,9,10].

While family history may justify increased cancer surveillance, misinterpretation of VUS results may result in risk-reducing surgeries in some patients [11]. This illustrates the need to educate both patients and healthcare providers about VUS results, while simultaneously using the opportunity to highlight the ongoing importance of considering familial cancer risks. Through this study, we sought to develop, evaluate, and refine novel educational materials to explain VUS results and educate individuals on how sharing information about a personal or family history of cancer remains useful as it can guide cancer risk management among family members.

2. Methods

We utilized an iterative process that began with an educational needs assessment to inform the development of VUS educational materials. This was followed by a three-step evaluation of the materials interspersed with several rounds of revisions. Our methods were determined to constitute an evaluation of educational materials by the University of South Florida’s Institutional Review Board (IRB) rather than human subjects research. Nevertheless, all individuals who provided feedback as part of our process received an informational sheet (similar to an informed consent document) and consented to reviewing the materials and answering questions while being recorded.

2.1. Educational Needs Assessment and Materials Development

The primary goal of our needs assessment was to identify common misconceptions, key information, or messages that might be useful in designing VUS educational materials. To achieve this goal, we reviewed the relevant VUS literature and analyzed de-identified interview transcripts from six women with a VUS in a hereditary breast cancer risk gene that had been conducted during a prior research effort to understand cancer risk management and genetic test results disclosure [12].

Themes and supporting examples from both the literature and interview transcripts were independently extracted by two team members (DC and MK) with expertise in health education and behavior. Findings were then combined, categorized, and discussed with the assistance of additional evaluation from team members, including experts in health communication, genetics, and anthropology. The team revised and recategorized themes until an agreement was reached. Team members subsequently used findings from the needs assessment to modify an existing audio/visual tool and to create additional educational materials.

2.2. Materials Evaluation

The three-step evaluation process included an assessment of materials based on criteria from an established evaluation rubric, followed by two rounds of feedback elicited from individuals with a VUS, as well as behavioral scientists and genetics experts who were not involved in development. First, team members used the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Clear Communication Index (CCI) Score Sheet [13] to assess the materials’ main messages, language level, information design, and behavioral recommendations [13]. A score of 1 was given when the material met criteria for each of the various aspects in the checklist. A score of 0 was assigned when the material did not meet the criteria. Scores of 90 and above were considered passing.

In addition to evaluating the materials using the CCI, team members solicited two rounds of feedback. The first round of feedback on the materials was elicited during semi-structured interviews and a focus group. Semi-structured interviews were conducted with two individuals from the Inherited Cancer Registry (ICARE) [14] who were confirmed to have a VUS and with one genetic counselor recruited from the National Society of Genetic Counselors (NSGC) website. A subsequent focus group to collect additional feedback was conducted among four individuals, including a genetic counselor, clinical geneticist, and two PhD-level scientists with expertise in public health, behavioral science, and hereditary cancer. The first round of feedback was used to improve the acceptability, clarity, and appropriateness of the educational materials, and revisions were made (as outlined in Section 3. Results and Refinement of Educational Materials). Subsequently, to evaluate the revisions to the materials, a second round of feedback was elicited during interviews with 10 different individuals from ICARE who were confirmed to have a VUS result in a cancer risk gene. This additional feedback supported earlier changes made to the materials and was used to finalize and provide preliminary support for the potential efficacy of the materials, as described in Section 3. Results and Refinement of Educational Materials.

Interviews for both rounds of feedback, as well as the focus group, were conducted via virtual video conferencing to allow participants to review the materials and describe their impressions in real-time. After participants provided initial feedback throughout the materials review, questions were asked to elicit more feedback on the material’s understandability, appropriateness, and acceptability. Specific to the second round of feedback, additional questions were asked to assess the usefulness of materials in sharing information with family members and to determine if participants’ perceptions changed regarding a VUS or cancer risks. Individual interviews and the focus group were recorded, and responses were coded and summarized into Microsoft Excel documents that included a list of recommendations for what to change or fix, as well as other emergent themes. Specific to the second round of feedback, themes were further organized into categories and subcategories with several exemplary quotes being extracted from interview recordings to illustrate key findings.

3. Results and Refinement of Educational Materials

This section summarizes findings from each step in the development and subsequent evaluation process and provides a few examples of changes and refinements made to the materials.

3.1. Findings from the Educational Needs Assessment and Materials Development

First, no published research studies were identified that detailed the development or evaluation of educational materials designed specifically for patients with a VUS in a cancer risk gene. However, an online tool was identified to help family members of a patient with a VUS understand VUS results, with the goal of recruiting family members into variant interpretation research studies [15]. This online tool did not describe the development of their information, nor did it include materials designed to increase family sharing of cancer risk information and cancer screening.

In general, the literature review findings highlighted difficulties patients have in understanding their VUS result and their struggle to accept the lack of healthcare recommendations [6,7,8,9,10]. Studies report how some non-genetics providers have misinterpreted VUS results and, in some cases, even recommended inappropriate medical interventions, such as a prophylactic mastectomy, for VUS results that were eventually reclassified as benign [16,17]. Patients also tend to misinterpret their own VUS results and may communicate inappropriate or confusing messages to family members [18,19]. When patients’ explanations are less reassuring and clear, it is more likely that their family members will perceive cancer in the family as hereditary, and the VUS as being associated with higher cancer risks [20].

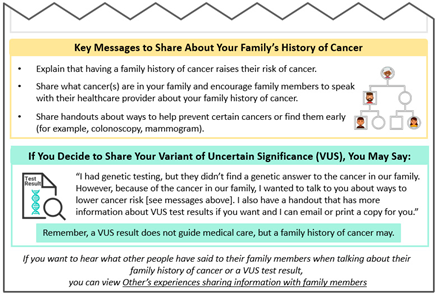

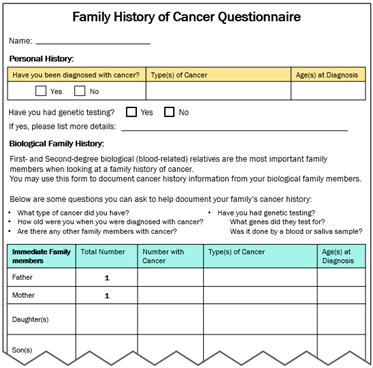

Second, findings from our analysis of de-identified interview transcripts were also used to develop VUS educational materials (see Supplemental Table S1 for characteristics of the six participants with a VUS who had consented previously). Some participants expressed initial confusion over their VUS results, which then turned into frustration due to the lack of impact these results have on medical management. In contrast, other patients seemed to understand that although the results do not change anything now, it might be important for family members to know about a VUS in the event that more information is found about the VUS in the future. These findings informed messages included in our “VUS Video: Understanding your VUS Test Result” and “Key Messages to Share (VUS/Family History)” educational materials.

When prompted to offer advice to other individuals who might receive a VUS result, one participant recommended disseminating risk information throughout the family in steps, starting with the family members perceived to be the most supportive. Although one patient expressed that sharing VUS results should be considered a necessity, another described how they will only share their VUS with family members if it is reclassified as a GPV. Finally, interview transcripts revealed that hearing about others’ experiences may be helpful. As such, we created educational materials entitled “Others’ Experiences with VUS Test Results” and “Experiences with Sharing Cancer Family History.”

Together the literature review findings and the analysis of interview transcripts with patients who have a VUS provided a rationale for developing VUS educational materials (see column entitled “Rationale to Inform Intervention Components” in Table 1) and informed the content of materials (see Table 1 for descriptions of the materials and screenshots).

Table 1.

Variant of Uncertain Significance (VUS) educational intervention components.

3.2. Evaluation: Clear Communication Index (CCI) Results and Revision

When evaluated, the educational materials initially scored 60% according to the CCI. Reasons for point deductions include the materials having three main messages as opposed to a single main message, and the call-to-action was listed in the passive voice. Points were also lost because some unfamiliar terms were only defined but not further explained and because some numbers were presented in only one way; for example, lifetime risks for cancer in various scenarios were listed only as percentages.

The materials scored high in clarity and communication because they included a call-to-action promoting family sharing of cancer risk information, used whole numbers when describing the efficacy of mammograms and colonoscopies, and explained how a family history of cancer can increase cancer risks even when no genetic cause is found. Points were also assigned because materials acknowledged the benefits associated with the recommended behavior.

Several changes were incorporated into the materials to improve the CCI, resulting in a score of 90%. This score was considered to be acceptable since some of the points were lost because risks of mammograms and colonoscopies were not explained to keep these respective handouts to one page. Points were also lost because the intervention included materials about VUS results as well as cancer screening based on family history, and the landing page helped guide individuals to the different resources rather than containing the main messages for each of the key materials. Points were not deducted for following the requests of participants to add a number to one of the handouts. This number was stated in the video and was included in a visual there, but the audience believed it was straightforward and enabled the handout to remain within one page.

3.3. Evaluation: Feedback and Materials Refinement (Round One)

Both of the patients and the genetic counselor who provided initial feedback reported overall satisfaction with the materials, but they also offered a few minor critiques concerning the language used and the design of the materials. For example, one patient shared the importance of having a primary care physician organize, interpret, and manage screenings, given that it is difficult for patients to be solely responsible. Another patient expressed some initial confusion about the VUS result, but after viewing our VUS educational video, she accurately described why her VUS did not explain her strong family history of cancer. The genetic counselor’s feedback focused on the benefit of educational materials regarding modifiable risk factors for cancer (e.g., tobacco use, excessive sun exposure), which they suggested could be incorporated into the video’s “Learn More” sections.

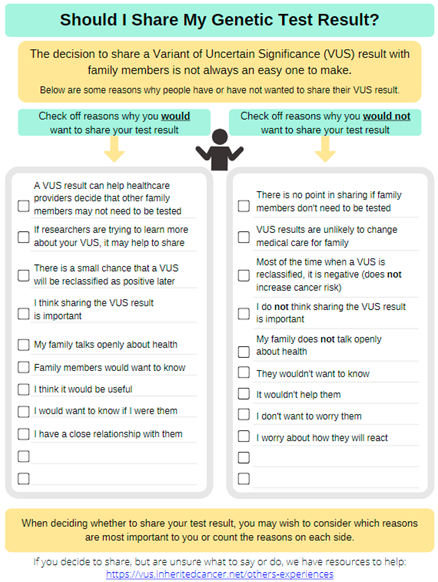

Focus group members appreciated the simple language used and overall material intent. A large portion of the focus group discussion centered on the decisional balance handout that listed “pros” and “cons” of sharing information about a family history of cancer. The group liked the use of this same decisional balance approach for material on sharing VUS results, because VUS results are not clinically actionable; however, they were concerned that the “cons” of sharing information about a family history of cancer may create more hesitancy in communicating cancer risk information. Given that a family history of certain cancers may change medical care for close relatives, the group felt it was important to promote family sharing while still acknowledging the concerns people may have.

Multiple changes were made to address both minor and major constructive feedback from these interviews and the focus group (see Supplemental Table S2). As one example, the “Sharing family history information” handout was made into a checklist of reasons for sharing, and the considerations (or potential cons) were included as part of others’ experiences illustrating ways to respond to family member reactions.

3.4. Evaluation: Results and Materials Refinement (Round Two)

The second round of feedback primarily uncovered minor improvements or edits from the 10 interviewees in round two of the evaluation (see Supplemental Table S3 for participant demographics). The video format was preferred by five participants, though three preferred the handout format (Supplemental Figure S1). All 10 interviewees commented on how the material was “concise”, “succinct”, “straight-to-the-point”, and “only tells you what you need to know”.

Overall, interview participants described the material as effective at improving their understanding about their VUS results. As one participant shared, “…These materials would have changed my perception and knowledge of a VUS when I first got my result”. Furthermore, some interviewees stated that the materials clarified their confusion when they received their initial VUS results. One participant said “It’s a clear description of a VUS that clears up the confusion and ambiguity associated with a VUS result”. Another interviewee shared “I have been confused as to what all that [referring to their VUS result] meant. I did not know that and just learned that from this [referring to VUS materials]”.

Interview participants also described the VUS materials as “empowering” and provided clear action steps, which reduced fear. For example, one participant said, “I now know what to do and that makes it not so scary”. Additionally, several interviewees noted the different reasons provided in the “Sharing your family’s history of cancer” handout and the quotes in the “Others’ experiences” section reflected how they felt or was similar to their own situation when talking with family members, with one participant saying “[The patient experience where] he mentioned a family history of cancer three times and his brother finally got his colonoscopy, it sounds exactly like my experiences”.

Participants reported that the materials would be helpful in sharing information about a VUS result, as well as sharing information about one’s family history of cancer. For instance, one participant shared, “I think people really struggle with what to say, and if you spoon-feed them, then that’s going to make it so much easier for them to share this information”. Indeed, several interviewees expressed that they wished the materials were more persuasive in sharing a VUS result; however, the main purpose of the intervention was to make it clear that sharing a VUS result is an individual preference, and it does not impact their family’s medical care (unlike a GPV). One participant noted that we achieved this goal by stating the material is “pretty unbiased” and “doesn’t seem like it’s trying to push you in any direction”. Last, all 10 interviewees indicated they would share these materials.

Although the feedback was predominantly positive (see Supplemental Table S4), there were some constructive comments (see Supplemental Table S5). For example, some interviewees expressed negative feelings evoked by a graphic of a scale (or balance) that was used to represent the weighing of the pros and cons on the “Deciding about Sharing Your Genetic Test Result” handout. That image was subsequently replaced by another image of a human silhouette shrugging. Furthermore, interview participants had mixed feelings on the intervention’s color scheme.

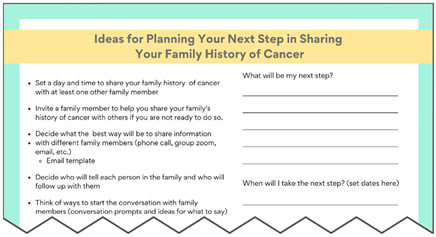

Several minor changes were implemented based on feedback from round two (noted in Supplemental Table S5). For example, we added guidance on which family members are the most important to talk to and offer additional “action items” to give patients directions/next steps they can take after learning about their VUS result. Due to the inability to garner consensus, the research team voted to keep the original color scheme.

4. Discussion

Through our study, we describe a systematic multi-step approach to the development, evaluation, and refinement of materials designed to educate patients and healthcare providers that a VUS result does not change medical care yet it remains important to share personal and family cancer information with family members. Comments from the final round of evaluation suggest these materials can fulfill the need to help patients with VUS results understand their results [21] and improve communication about cancer risks, as well as screening and prevention options between and among family members [6,7,8,9,10]. Additionally, our educational materials not only utilize but also extend prior research in multiple ways.

First, we addressed known misconceptions leading to inappropriate medical decisions. Patients struggle to understand their VUS results and thus often believe their cancer risks remain high because of the result [19,22]. The ambiguity inherent in a VUS result means that it should not be used to alter medical care. However, the lack of clear action steps also creates uncertainty for patients and healthcare providers [11,23,48], which can result in inappropriate medical decisions [21,25]. Our materials emphasized that a VUS result should not be used to change medical care, but rather medical management should be based on a family history of cancer. The potential efficacy of these materials to educate patients about VUS results for cancer genes is evidenced by the respondents’ ability to relay back messaging that the VUS result would not impact medical management screening, treatments, and other health risks.

Second, we included two decision-making support resources to help patients who have a VUS result—(1) to consider the pros and cons of sharing their VUS result and (2) to identify their own reasons for sharing their personal and family history of cancer with family members. These two separate resources should help distinguish between these decisions and reflect how the benefits of sharing a VUS result are less clear than the benefits of sharing family history information. Thus, sharing a VUS result should be based on the patients’ preferences when considering pros and cons together as part of a decisional balance exercise. In contrast, considering the benefits of sharing a family history of cancer first and then reviewing patients’ experiences (for anyone who has concerns) should help motivate participants to share this information, while also addressing ways to overcome the reservations they may have (illustrated by patients’ experiences). Participants throughout the evaluation believed that these resources would be useful and extant research also notes that sharing genetic test results with family members is an effective coping strategy [24].

Third, as alluded to above, we included patients’ experiences with sharing VUS results, as well as sharing their family history of cancer. Integrating patient narratives such as quotes provides psychosocial information that resonates with patients, helping them to process and manage information [44] and may motivate them to adopt certain health behaviors [45]. Specific quotes that illustrate different coping responses can demonstrate appropriate cancer risk management decisions and forecast possible reactions that family members may have if patients share information [46,49]. A novel aspect of this section in our intervention is the use of real patients’ quotes from extant research [44], as well as interviews from our prior study. Importantly, our participants who evaluated the educational materials reported that the patients’ quotes resonated with their personal experiences when sharing their VUS result and/or family history of cancer with family members.

Strengths and Limitations

Our study has several strengths, including the purposeful utilization of the relevant literature and patients’ VUS experiences and a clear demonstration in Table 1 explicating how we developed our intervention’s educational materials. As noted earlier, no research studies were found explaining not only the development, but also the evaluation of educational materials for patients with a VUS in a cancer risk gene. Another strength is the iterative evaluation process. We sought out not only feedback from patients with a VUS result, but also other important stakeholders including experts in genetics and public health and behavioral science. Despite these strengths, there remain some limitations including the fact that the participants in this study had already shared information about their VUS result and/or family history of cancer; thus, we may be missing perspectives from patients who are hesitant or resistant to sharing. Second, the views may not be representative given that participants included only one male and three individuals who identified as racial/ethnic minorities.

5. Conclusions

This study reports on the development, evaluation, and refinement of novel educational materials that explain that VUS results should not change medical care and educates patients on how sharing information about a personal or family history of cancer may be useful to family members. By addressing known misconceptions about VUS results, providing decision making support for sharing information, and integrating patients’ experiences, the goal of our educational intervention is to help patients with VUS results manage their uncertainty, understand their cancer risks, and facilitate communication with family members. While recognizing that these educational materials were designed for patients, we believe that these materials may also assist healthcare providers in explaining VUS results and promote appropriate cancer risk management decisions. Future studies are now needed to test whether these materials are useful for ensuring accurate information is shared with family members.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/curroncol31060256/s1, Figure S1: Material format preference from second round of interviews; Table S1: Demographics of the six interview participants from the needs assessment; Table S2: Feedback from the needs assessment interviews and focus group; Table S3: Demographics of interview participants from materials’ validation; Table S4: Positive feedback organized by category and subcategory with supportive illustrative quotes; Table S5: Constructive feedback organized by category and subcategory with supportive illustrative quotes and description of changes made.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.C., M.D., D.B., M.K., G.H., A.W., P.H. and T.P.; Data curation, D.B., M.K. and P.H.; Formal analysis, D.B., M.K. and P.H.; Funding acquisition, D.C. and T.P.; Investigation, D.B. and M.K.; Methodology, D.C., M.D., M.K. and T.P.; Project administration, D.C., M.D., A.W., P.H. and T.P.; Resources, D.C., M.K. and T.P.; Supervision, D.C., M.D., G.H. and T.P.; Writing—original draft, D.C. and M.D.; Writing—review and editing, D.C., M.D., D.B., M.K., G.H., A.W., P.H. and T.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health through funding from the National Cancer Institute (U01CA254832).

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of South Florida (STUDY001784, 2 December 2020).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets presented in this article are not readily available because the data are part of an ongoing study. Requests to access the datasets should be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funder had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analysis, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

| VUS | Variant of Uncertain Significance |

| IRB | Institutional Review Board |

| CDC | Centers for Disease Control and Prevention |

| CCI | Clear Communication Index |

| ICARE | Inherited Cancer Registry |

| NSGC | National Society of Genetic Counselors |

| COM-B | Capability, Opportunity, Motivation-Behavior |

| GPV | Germline Pathogenic or Likely Pathogenic Variant |

References

- Sehgal, R.; Sheahan, K.; O’Connell, P.R.; Hanly, A.M.; Martin, S.T.; Winter, D.C. Lynch Syndrome: An Updated Review. Genes 2014, 5, 497–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Apostolou, P.; Fostira, F. Hereditary Breast Cancer: The Era of New Susceptibility Genes. Biomed. Res. Int. 2013, 2013, 747318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mersch, J.; Brown, N.; Pirzadeh-Miller, S.; Mundt, E.; Cox, H.C.; Brown, K.; Aston, M.; Esterling, L.; Manley, S.; Ross, T. Prevalence of Variant Reclassification Following Hereditary Cancer Genetic Testing. JAMA 2018, 320, 1266–1274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Richards, S.; Aziz, N.; Bale, S.; Bick, D.; Das, S.; Gastier-Foster, J.; Grody, W.W.; Hegde, M.; Lyon, E.; Spector, E.; et al. Standards and Guidelines for the Interpretation of Sequence Variants: A Joint Consensus Recommendation of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics and the Association for Molecular Pathology. Genet. Med. 2015, 17, 405–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- NCCN. Genetic/Familial High-Risk Assessment: Breast, Ovarian, and Pancreatic. In NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology (NCCN Guidelines); National Comprehensive Cancer Network: Plymouth Meeting, PA, USA, Version 1; 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Bowen, D.J.; Hay, J.L.; Harris-Wai, J.N.; Meischke, H.; Burke, W. All in the Family? Communication of Cancer Survivors with Their Families. Fam. Cancer 2017, 16, 597–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinney, A.Y.; Boonyasiriwat, W.; Walters, S.T.; Pappas, L.M.; Stroup, A.M.; Schwartz, M.D.; Edwards, S.L.; Rogers, A.; Kohlmann, W.K.; Boucher, K.M.; et al. Telehealth Personalized Cancer Risk Communication to Motivate Colonoscopy in Relatives of Patients with Colorectal Cancer: The Family CARE Randomized Controlled Trial. J. Clin. Oncol. 2014, 32, 654–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eijzenga, W.; de Geus, E.; Aalfs, C.M.; Menko, F.H.; Sijmons, R.H.; de Haes, H.C.J.M.; Smets, E.M.A. How to Support Cancer Genetics Counselees in Informing At-Risk Relatives? Lessons from a Randomized Controlled Trial. Patient Educ. Couns. 2018, 101, 1611–1619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wiseman, M.; Dancyger, C.; Michie, S. Communicating Genetic Risk Information within Families: A Review. Fam. Cancer 2010, 9, 691–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chivers Seymour, K.; Addington-Hall, J.; Lucassen, A.M.; Foster, C.L. What Facilitates or Impedes Family Communication Following Genetic Testing for Cancer Risk? A Systematic Review and Meta-Synthesis of Primary Qualitative Research. J. Genet. Couns. 2010, 19, 330–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurian, A.W.; Li, Y.; Hamilton, A.S.; Ward, K.C.; Hawley, S.T.; Morrow, M.; McLeod, M.C.; Jagsi, R.; Katz, S.J. Gaps in Incorporating Germline Genetic Testing Into Treatment Decision-Making for Early-Stage Breast Cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2017, 35, 2232–2239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dean, M.; Tezak, A.L.; Johnson, S.; Weidner, A.; Almanza, D.; Pal, T.; Cragun, D.L. Factors That Differentiate Cancer Risk Management Decisions among Females with Pathogenic/Likely Pathogenic Variants in PALB2, CHEK2, and ATM. Genet. Med. 2023, 25, 100945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CDC. The CDC Clear Communication Index. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/ccindex/index.html (accessed on 26 March 2024).

- Pal, T.; Radford, C.; Weidner, A.; Tezak, A.L.; Cragun, D.; Wiesner, G.L. The Inherited Cancer Registry (ICARE) Initiative: An Academic-Community Partnership for Patients and Providers. Oncol. Issues 2018, 33, 54–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrett, L.T.; Hickman, N.; Jacobson, A.; Bennett, R.L.; Amendola, L.M.; Rosenthal, E.A.; Shirts, B.H. Family Studies for Classification of Variants of Uncertain Classification: Current Laboratory Clinical Practice and a New Web-Based Educational Tool. J. Genet. Couns. 2016, 25, 1146–1156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, M.L.; Cerrato, F.; Bennett, R.L.; Jarvik, G.P. Follow-up of Carriers of BRCA1 and BRCA2 Variants of Unknown Significance: Variant Reclassification and Surgical Decisions. Genet. Med. 2011, 13, 998–1005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Macklin, S.K.; Jackson, J.L.; Atwal, P.S.; Hines, S.L. Physician Interpretation of Variants of Uncertain Significance. Fam. Cancer 2019, 18, 121–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reuter, C.; Chun, N.; Pariani, M.; Hanson-Kahn, A. Understanding Variants of Uncertain Significance in the Era of Multigene Panels: Through the Eyes of the Patient. J. Genet. Couns. 2019, 28, 878–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medendorp, N.M.; van Maarschalkerweerd, P.E.A.; Murugesu, L.; Daams, J.G.; Smets, E.M.A.; Hillen, M.A. The Impact of Communicating Uncertain Test Results in Cancer Genetic Counseling: A Systematic Mixed Studies Review. Patient Educ. Couns. 2020, 103, 1692–1708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vos, J.; Jansen, A.M.; Menko, F.; Van Asperen, C.J.; Stiggelbout, A.M.; Tibben, A. Family Communication Matters: The Impact of Telling Relatives about Unclassified Variants and Uninformative DNA-Test Results. Genet. Med. 2011, 13, 333–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bramanti, S.M.; Trumello, C.; Lombardi, L.; Cavallo, A.; Stuppia, L.; Antonucci, I.; Babore, A. Uncertainty Following an Inconclusive Result from the BRCA1/2 Genetic Test: A Review about Psychological Outcomes. World J. Psychiatry 2021, 11, 189–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eccles, D.M.; Mitchell, G.; Monteiro, A.N.A.; Schmutzler, R.; Couch, F.J.; Spurdle, A.B.; Gómez-García, E.B. ENIGMA Clinical Working Group BRCA1 and BRCA2 Genetic Testing-Pitfalls and Recommendations for Managing Variants of Uncertain Clinical Significance. Ann. Oncol. 2015, 26, 2057–2065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makhnoon, S.; Shirts, B.H.; Bowen, D.J. Patients’ Perspectives of Variants of Uncertain Significance and Strategies for Uncertainty Management. J. Genet. Couns. 2019, 28, 313–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Solomon, I.; Harrington, E.; Hooker, G.; Erby, L.; Axilbund, J.; Hampel, H.; Semotiuk, K.; Blanco, A.; Klein, W.M.P.; Giardiello, F.; et al. Lynch Syndrome Limbo: Patient Understanding of Variants of Uncertain Significance. J. Genet. Couns. 2017, 26, 866–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vos, J.; Otten, W.; van Asperen, C.; Jansen, A.; Menko, F.; Tibben, A. The Counsellees’ View of an Unclassified Variant in BRCA1/2: Recall, Interpretation, and Impact on Life. Psychooncology 2008, 17, 822–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, S.-T.; Sun, S.; Lie, D.; Met-Domestici, M.; Courtney, E.; Menon, S.; Lim, G.H.; Ngeow, J. Factors Influencing the Decision to Share Cancer Genetic Results among Family Members: An in-Depth Interview Study of Women in an Asian Setting. Psychooncology 2018, 27, 998–1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cypowyj, C.; Eisinger, F.; Huiart, L.; Sobol, H.; Morin, M.; Julian-Reynier, C. Subjective Interpretation of Inconclusive BRCA1/2 Cancer Genetic Test Results and Transmission of Information to the Relatives. Psychooncology 2009, 18, 209–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frost, C.J.; Venne, V.; Cunningham, D.; Gerritsen-McKane, R. Decision Making with Uncertain Information: Learning from Women in a High Risk Breast Cancer Clinic. J. Genet. Couns. 2004, 13, 221–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elwyn, G.; Frosch, D.; Rollnick, S. Dual Equipoise Shared Decision Making: Definitions for Decision and Behaviour Support Interventions. Implement. Sci. 2009, 4, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petersen, J.; Koptiuch, C.; Wu, Y.P.; Mooney, R.; Elrick, A.; Szczotka, K.; Keener, M.; Pappas, L.; Kanth, P.; Soisson, A.; et al. Patterns of Family Communication and Preferred Resources for Sharing Information among Families with a Lynch Syndrome Diagnosis. Patient Educ. Couns. 2018, 101, 2011–2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brewer, H.R.; Jones, M.E.; Schoemaker, M.J.; Ashworth, A.; Swerdlow, A.J. Family History and Risk of Breast Cancer: An Analysis Accounting for Family Structure. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2017, 165, 193–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butterworth, A.S.; Higgins, J.P.T.; Pharoah, P. Relative and Absolute Risk of Colorectal Cancer for Individuals with a Family History: A Meta-Analysis. Eur. J. Cancer 2006, 42, 216–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ochs-Balcom, H.M.; Kanth, P.; Cannon-Albright, L.A. Early-Onset Colorectal Cancer Risk Extends to Second- and Third-Degree Relatives. Cancer Epidemiol. 2021, 73, 101973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsai, M.-H.; Xirasagar, S.; Li, Y.-J.; de Groen, P.C. Colonoscopy Screening Among US Adults Aged 40 or Older With a Family History of Colorectal Cancer. Prev. Chronic Dis. 2015, 12, E80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miller, W.R.; Rollnick, S. Motivational Interviewing: Helping People Change, 3rd ed.; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2013; ISBN 978-1-60918-227-4. [Google Scholar]

- Dean, M.; Rauscher, E.A. Men’s and Women’s Approaches to Disclosure About BRCA-Related Cancer Risks and Family Planning Decision-Making. Qual. Health Res. 2018, 28, 2155–2168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meppelink, C.S.; Smit, E.G.; Buurman, B.M.; van Weert, J.C.M. Should We Be Afraid of Simple Messages? The Effects of Text Difficulty and Illustrations in People With Low or High Health Literacy. Health Commun. 2015, 30, 1181–1189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houts, P.S.; Doak, C.C.; Doak, L.G.; Loscalzo, M.J. The Role of Pictures in Improving Health Communication: A Review of Research on Attention, Comprehension, Recall, and Adherence. Patient Educ. Couns. 2006, 61, 173–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tea, M.-K.M.; Tan, Y.Y.; Staudigl, C.; Eibl, B.; Renz, R.; Asseryanis, E.; Berger, A.; Pfeiler, G.; Singer, C.F. Improving Comprehension of Genetic Counseling for Hereditary Breast and Ovarian Cancer Clients with a Visual Tool. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0200559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailey, R.R. Goal Setting and Action Planning for Health Behavior Change. Am. J. Lifestyle Med. 2017, 13, 615–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daly, M.B.; Montgomery, S.; Bingler, R.; Ruth, K. Communicating Genetic Test Results within the Family: Is It Lost in Translation? A Survey of Relatives in the Randomized Six-Step Study. Fam. Cancer 2016, 15, 697–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seiffert, K.; Thoene, K.; Eulenburg, C.Z.; Behrens, S.; Schmalfeldt, B.; Becher, H.; Chang-Claude, J.; Witzel, I. The Effect of Family History on Screening Procedures and Prognosis in Breast Cancer Patients—Results of a Large Population-Based Case-Control Study. Breast 2020, 55, 98–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pengchit, W.; Walters, S.T.; Simmons, R.G.; Kohlmann, W.; Burt, R.W.; Schwartz, M.D.; Kinney, A.Y. Motivation-Based Intervention to Promote Colonoscopy Screening: An Integration of a Fear Management Model and Motivational Interviewing. J. Health Psychol. 2011, 16, 1187–1197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conley, C.C.; Davidson, L.G.; Scherr, C.L.; Dean, M. Developing Theory-Driven Narrative Messages with Personal Stories: A Step-by-Step Guide. Psycho-Oncology 2022, 31, 2113–2121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Graaf, A.; Hoeken, H.; Sanders, J.; Beentjes, J.W.J. Identification as a Mechanism of Narrative Persuasion. Commun. Res. 2012, 39, 802–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montgomery, S.V.; Barsevick, A.M.; Egleston, B.L.; Bingler, R.; Ruth, K.; Miller, S.M.; Malick, J.; Cescon, T.P.; Daly, M.B. Preparing Individuals to Communicate Genetic Test Results to Their Relatives: Report of a Randomized Control Trial. Fam. Cancer 2013, 12, 537–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dean, M.; Tezak, A.L.; Johnson, S.; Pierce, J.K.; Weidner, A.; Clouse, K.; Pal, T.; Cragun, D. Sharing Genetic Test Results with Family Members of BRCA, PALB2, CHEK2, and ATM Carriers. Patient Educ. Couns. 2021, 104, 720–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Makhnoon, S.; Bowen, D.J.; Shirts, B.H.; Fullerton, S.M.; Meischke, H.W.; Larson, E.B.; Ralston, J.D.; Leppig, K.; Crosslin, D.R.; Veenstra, D.; et al. Relationship between Genetic Knowledge and Familial Communication of CRC Risk and Intent to Communicate CRCP Genetic Information: Insights from FamilyTalk eMERGE III. Transl. Behav. Med. 2021, 11, 563–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cragun, D.; Beckstead, J.; Farmer, M.; Hooker, G.; Dean, M.; Matloff, E.; Reid, S.; Tezak, A.; Weidner, A.; Whisenant, J.G.; et al. IMProving Care After Inherited Cancer Testing (IMPACT) Study: Protocol of a Randomized Trial Evaluating the Efficacy of Two Interventions Designed to Improve Cancer Risk Management and Family Communication of Genetic Test Results. BMC Cancer 2021, 21, 1099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).