Identifying Barriers to Effective Cancer Pain Management in Oman: Implications for Palliative Care

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods and Study Design

2.1. Setting and Participants

2.2. Study Instruments

2.2.1. Demographic and Disease-Related Information Questionnaires

2.2.2. Barriers Questionnaire II-12 (BQII-12) (12 Items)

2.2.3. Patient Pain Questionnaire (PPQ) (16 Items)

2.2.4. Statistics

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Statistics

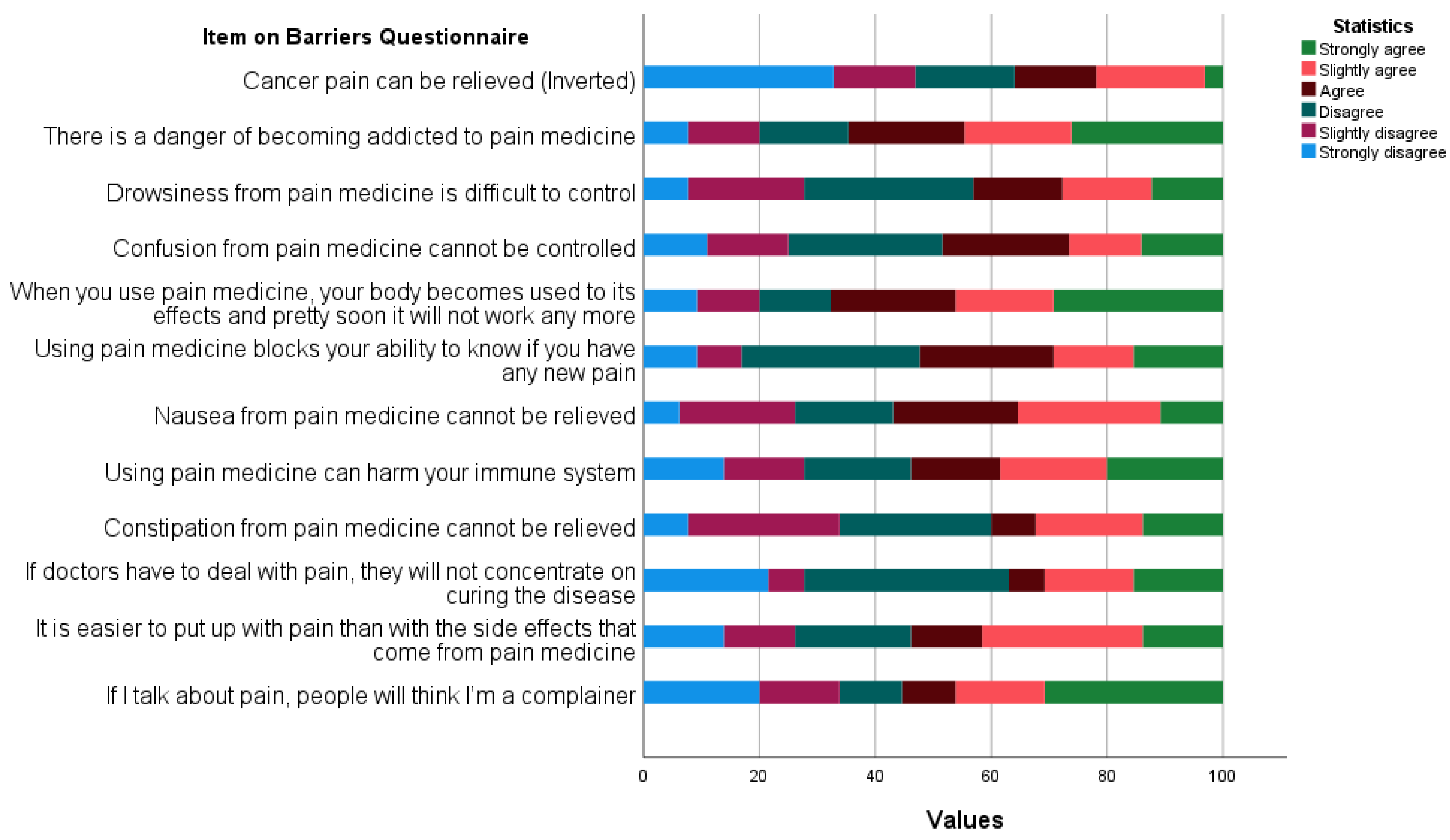

3.2. Response to Barriers Questionnaire

3.3. Relationship between the BQ Score and Other Variables

3.4. Response to the Patient Pain Questionnaire

4. Discussion

5. Limitations

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Van Den Beuken-Van Everdingen, M.H.J.; Hochstenbach, L.M.J.; Joosten, E.A.J.; Tjan-Heijnen, V.C.G.; Janssen, D.J.A. Update on Prevalence of Pain in Patients with Cancer: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Pain Symptom Manag. 2016, 51, 1070–1090.e9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nardelli, C.; Granata, I.; Nunziato, M.; Setaro, M.; Carbone, F.; Zulli, C.; Pilone, V.; Capoluongo, E.D.; De Palma, G.D.; Corcione, F.; et al. 16S rRNA of Mucosal Colon Microbiome and CCL2 Circulating Levels Are Potential Biomarkers in Colorectal Cancer. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faris, M.; Al-Bahrani, B.; Emam Khalifa, A.; Ahmad, N. Evaluation of the prevalence, pattern and management of cancer pain in Oncology Department, The Royal Hospital, Oman. Gulf J. Oncolog. 2007, 1, 23–28. [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez, C.; Ji, M.; Wang, H.L.; Padhya, T.; Mcmillan, S.C. Cancer Pain and Quality of Life. J. Hosp. Palliat. Nurs. 2019, 21, 116–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- te Boveldt, N.; Vernooij-Dassen, M.; Burger, N.; Ijsseldijk, M.; Vissers, K.; Engels, Y. Pain and its interference with daily activities in medical oncology outpatients. Pain Physician 2013, 16, 379–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raphael, J.; Hester, J.; Ahmedzai, S.; Barrie, J.; Farqhuar-Smith, P.; Williams, J.; Urch, C.; Bennett, M.I.; Robb, K.; Simpson, B.; et al. Cancer Pain: Part 2: Physical, Interventional and Complimentary Therapies; Management in the Community; Acute, Treatment-Related and Complex Cancer Pain: A Perspective from the British Pain Society Endorsed by the UK Association of Palliative Medicine and. Pain Med. 2010, 11, 872–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.C.; Chou, P.L.; Wu, S.L.; Chang, Y.C.; Lai, Y. Long-term effectiveness of a patient and family pain education program on overcoming barriers to management of cancer pain. Pain 2006, 122, 271–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobsen, R.; Møldrup, C.; Christrup, L.; Sjøgren, P. Patient-related barriers to cancer pain management: A systematic exploratory review. Scand. J. Caring Sci. 2009, 23, 190–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Qadire, M. Patient-related barriers to cancer pain management in Jordan. J. Pediatr. Hematol. Oncol. 2012, 34 (Suppl. S1), S28–S31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colak, D.; Oguz, A.; Yazilitas, D.; Imamoglu, I.G.; Altinbas, M. Morphine: Patient knowledge and attitudes in the central Anatolia part of Turkey. Asian Pacific J. Cancer Prev. 2014, 15, 4983–4988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makhlouf, S.M.; Pini, S.; Ahmed, S.; Bennett, M.I. Managing Pain in People with Cancer—A Systematic Review of the Attitudes and Knowledge of Professionals, Patients, Caregivers and Public. J. Cancer Educ. 2020, 35, 214–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ward, S.E.; Hernandez, L. Patient-related barriers to management of cancer pain in Puerto Rico. Pain 1994, 58, 233–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jacobsen, R.; Liubarskiene, Z.; Møldrup, C.; Christrup, L.; Sjøgren, P.; Samsanavièiene, J. Barriers to cancer pain management: A review of empirical research. Medicina 2009, 45, 427–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koller, A.; Jahn, P. Developing a Short Form of the German Barriers Questionnaire II: A Validation Study in Four Steps. J. Pain Symptom Manag. 2018, 55, 458–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- City of Hope The Patient Pain Questionnaire (PPQ). 2012. Available online: https://www.cityofhope.org/sites/www/files/2022-05/patient-pain-management.pdf (accessed on 20 March 2024).

- Al Zaabi, A.; Al Shehhi, A.; Sayed, S.; Al Adawi, H.; Al Faris, F.; Al Alyani, O.; Al Asmi, M.; Al-Mirza, A.; Panchatcharam, S.; Al-Shaibi, M. Early Onset Colorectal Cancer in Arabs, Are We Dealing with a Distinct Disease? Cancers 2023, 15, 889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Atiyyat, N.M.H.; Vallerand, A.H. Patient-related attitudinal barriers to cancer pain management among adult Jordanian patients. Eur. J. Oncol. Nurs. 2018, 33, 56–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alodhayani, A.; Almutairi, K.M.; Vinluan, J.M.; Alsadhan, N.; Almigbal, T.H.; Alonazi, W.B.; Batais, M.A. Gender Difference in Pain Management Among Adult Cancer Patients in Saudi Arabia: A Cross-Sectional Assessment. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 628223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Obaid, A.; Al Hroub, A.; Al Rifai, A.; Alruzzieh, M.; Radaideh, M.; Tantawi, Y. Barriers to Effective Cancer Pain Management, Comparing the Perspectives of Physicians, Nurses, and Patients. Pain Manag. Nurs. 2023, 24, 498–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lou, F.; Shang, S. Attitudes towards pain management in hospitalized cancer patients and their influencing factors. Chinese J. Cancer Res. 2017, 29, 75–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baǧçivan, G.; Tosun, N.; Kömürcü, Ş.; Akbayrak, N.; Özet, A. Analysis of Patient-Related Barriers in Cancer Pain Management in Turkish Patients. J. Pain Symptom Manag. 2009, 38, 727–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ward, S.E.; Goldberg, N.; Miller-McCauley, V.; Mueller, C.; Nolan, A.; Pawlik-Plank, D.; Robbins, A.; Stormoen, D.; Weissman, D.E. Patient-related barriers to management of cancer pain. Pain 1993, 52, 319–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ward, S.E.; Berry, P.E.; Misiewicz, H. Concerns about Analgesics among Patients and Family Caregivers in a Hospice Setting. Res. Nurs. Health 1996, 19, 205–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silbermann, M.; Hassan, E.A. Cultural perspectives in cancer care: Impact of Islamic traditions and practices in Middle Eastern Countries. J. Pediatr. Hematol. Oncol. 2011, 33 (Suppl. S2), 81–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mercadante, S.; Adile, C.; Tirelli, W.; Ferrera, P.; Penco, I.; Casuccio, A. Barriers and Adherence to Pain Management in Advanced Cancer Patients. Pain Pract. 2021, 21, 388–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, B.O.; Liu, Y.; Wang, Y.H.; Hsu, H.T.; Chen, C.L.; Chou, P.L.; Hsu, W.C. Mediating Effect of Family Caregivers’ Hesitancy to Use Analgesics on Homecare Cancer Patients’ Analgesic Adherence. J. Pain Symptom Manag. 2018, 56, e9–e17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meghani, S.H.; Wool, J.; Davis, J.; Yeager, K.A.; Mao, J.J.; Barg, F.K. When Patients Take Charge of Opioids: Self-Management Concerns and Practices Among Cancer Outpatients in the Context of Opioid Crisis. J. Pain Symptom Manag. 2020, 59, 618–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choong, K.A. Islam and palliative care. Glob. Bioeth. 2015, 26, 28–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torresan, M.M.; Garrino, L.; Borraccino, A.; Macchi, G.; De Luca, A.; Dimonte, V. Adherence to treatment in patient with severe cancer pain: A qualitative enquiry through illness narratives. Eur. J. Oncol. Nurs. 2015, 19, 397–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Item | n | Proportion (%) | Attitude Score on BQ | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | |||

| Gender | ||||

| Men | 21 | 30.88 | 2.41 | 0.73 |

| Women | 47 | 69.11 | 2.57 | 0.88 |

| Age (Years) | ||||

| ≤44 | 36 | 53.73 | 2.40 | 0.87 |

| 45–59 | 27 | 40.30 | 2.68 | 0.82 |

| ≥60 | 4 | 5.97 | 2.52 | 0.61 |

| Education level | ||||

| Read and write | 13 | 19.11 | 2.42 | 0.61 |

| Primary education | 7 | 10.29 | 2.30 | 1.05 |

| High school diploma | 37 | 54.41 | 2.54 | 0.91 |

| Bachelor’s degree | 8 | 11.76 | 2.77 | 0.82 |

| Higher education | 2 | 2.94 | 2.58 | 0.94 |

| Missing | 1 | 1.47 | - | - |

| Marital Status | ||||

| Single | 12 | 17.65 | 2.92 | 0.62 |

| Married | 49 | 72.05 | 2.44 | 0.87 |

| Divorced | 5 | 7.35 | 2.83 | 0.29 |

| Primary Tumor | ||||

| Breast cancer | 24 | 36.76 | 2.34 | 1.00 |

| Oral, nasopharyngeal, esophageal, and gastrointestinal cancers | 18 | 26.47 | 2.66 | 0.49 |

| Kidney, ureter, bladder, ovarian cervical and uterine cancers | 10 | 16.17 | 2.53 | 1.00 |

| Lung cancer | 2 | 2.94 | 2.67 | 1.30 |

| Liver, pancreatic, and lymphoma | 1 | 1.47 | 3.17 | - |

| Other | 11 | 16.17 | 2.62 | 0.67 |

| Metastasis | ||||

| No | 24 | 35.29 | 2.23 | 0.89 |

| Yes | 44 | 64.71 | 2.64 | 0.78 |

| Previous Surgeries | ||||

| No | 24 | 35.29 | 2.60 | 0.84 |

| Yes | 44 | 64.70 | 2.47 | 0.84 |

| Domains | Patient | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Score (Mean ± SD) | Rank | Cronbach’s α * | |

| Tolerance | 3.17 ± 1.68 | 1 | 0.30 |

| Addiction | 3.06 ± 1.65 | 2 | 0.45 |

| Be Good | 2.75 ± 1.92 | 3 | 0.46 |

| Immune | 2.63 ± 1.73 | 4 | 0.67 |

| Masking | 2.57 ± 1.68 | 5 | 0.60 |

| Symptoms | 2.48 ± 0.87 | 6 | 0.67 |

| Distraction | 1.95 ± 1.74 | 7 | 0.36 |

| Fatalism | 1.73 ± 1.57 | 8 | 0.04 |

| BQ Total | 2.52 ± 0.84 | - | 0.73 |

| Male | 2.41 ± 0.73 | ||

| Female | 2.57 ± 0.88 | ||

| Variable | Sum of Squares | df | Mean Square | F | Sig. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BQTotal | Between Groups | 1.517 | 2 | 0.759 | 1.100 | 0.340 |

| Within Groups | 40.687 | 59 | 0.690 | |||

| Total | 42.204 | 61 | ||||

| Symptoms | Between Groups | 3.411 | 2 | 1.705 | 2.308 | 0.108 |

| Within Groups | 44.326 | 60 | 0.739 | |||

| Total | 47.737 | 62 | ||||

| Tolerance | Between Groups | 13.850 | 2 | 6.925 | 2.599 | 0.083 |

| Within Groups | 162.509 | 61 | 2.664 | |||

| Total | 176.359 | 63 | ||||

| Masking | Between Groups | 11.763 | 2 | 5.882 | 2.140 | 0.126 |

| Within Groups | 167.674 | 61 | 2.749 | |||

| Total | 179.437 | 63 | ||||

| Fatalism | Between Groups | 14.942 | 2 | 7.471 | 3.169 | * 0.049 |

| Within Groups | 141.471 | 60 | 2.358 | |||

| Total | 156.413 | 62 | ||||

| Distraction | Between Groups | 2.340 | 2 | 1.170 | 0.373 | 0.691 |

| Within Groups | 191.597 | 61 | 3.141 | |||

| Total | 193.938 | 63 | ||||

| BeGood | Between Groups | 0.013 | 2 | 0.007 | 0.002 | 0.998 |

| Within Groups | 232.924 | 61 | 3.818 | |||

| Total | 232.937 | 63 | ||||

| Addiction | Between Groups | 2.592 | 2 | 1.296 | 0.465 | 0.630 |

| Within Groups | 170.017 | 61 | 2.787 | |||

| Total | 172.609 | 63 | ||||

| Dependent Variable | (I) Age Categorized | (J) Age Categorized | Mean Difference (I-J) | Std. Error | Sig. | 95% Confidence Interval | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower Bound | Upper Bound | ||||||

| Fatalism | ≤44 | 45–59 | −0.330 | 0.405 | 0.696 | −1.30 | 0.642 |

| ≥60 | −2.030 * | 0.811 | * 0.040 | −3.98 | −0.078 | ||

| 45–59 | ≤44 | 0.330 | 0.404 | 0.696 | −0.642 | 1.301 | |

| ≥60 | −1.700 | 0.826 | 0.108 | −3.687 | 0.287 | ||

| ≥60 | ≤44 | 2.030 * | 0.811 | * 0.040 | 0.0788 | 3.980 | |

| 45–59 | 1.700 | 0.826 | 0.108 | −0.287 | 3.687 | ||

| Dependent Variable | Levene’s Test for Equality of Variance | t-Test for Equality of Means | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F | Sig. | t | df | (Sig.) | Mean Difference | Std. Error Difference | 95% Confidence Interval of the Difference | |||

| Lower | Upper | |||||||||

| Tolerance | Equal variances assumed | 2.309 | 0.134 | 2.562 | 63 | 0.013 | 1.111 | 0.434 | 0.244 | 0.244 |

| Equal variances not assumed | 2.390 | 31.283 | 0.023 | 1.111 | 0.465 | 0.163 | 2.059 | |||

| Dependent Variable | Levene’s Test for Equality of Variance | t-Test for Equality of Means | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F | Sig. | t | df | Sig. | Mean Difference | Std. Error Difference | 95% Confidence Interval of the Difference | |||

| Lower | Upper | |||||||||

| Addiction | Equal variances assumed | 5.751 | 0.019 | 2.545 | 63 | 0.013 | 1.054 | 0.415 | 0.226 | 1.883 |

| Equal variances not assumed | 2.349 | 34.434 | 0.025 | 1.054 | 0.450 | 0.143 | 1.967 | |||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ali Alaswami, H.; Al Musalami, A.A.; Al Saadi, M.H.; AlZaabi, A.A. Identifying Barriers to Effective Cancer Pain Management in Oman: Implications for Palliative Care. Curr. Oncol. 2024, 31, 2963-2973. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol31060225

Ali Alaswami H, Al Musalami AA, Al Saadi MH, AlZaabi AA. Identifying Barriers to Effective Cancer Pain Management in Oman: Implications for Palliative Care. Current Oncology. 2024; 31(6):2963-2973. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol31060225

Chicago/Turabian StyleAli Alaswami, Husain, Atika Ahmed Al Musalami, Muaeen Hamed Al Saadi, and Adhari Abdullah AlZaabi. 2024. "Identifying Barriers to Effective Cancer Pain Management in Oman: Implications for Palliative Care" Current Oncology 31, no. 6: 2963-2973. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol31060225

APA StyleAli Alaswami, H., Al Musalami, A. A., Al Saadi, M. H., & AlZaabi, A. A. (2024). Identifying Barriers to Effective Cancer Pain Management in Oman: Implications for Palliative Care. Current Oncology, 31(6), 2963-2973. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol31060225