Validation of the Canadian Version of the Shame and Stigma Scale for Head and Neck Cancer Patients

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Population and Procedure

2.2. Measures

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Description of the Study Population

3.2. Factor Analysis of the Shame and Stigma Scale

3.3. Descriptive Statistics for the Subscales and Items of the SSS

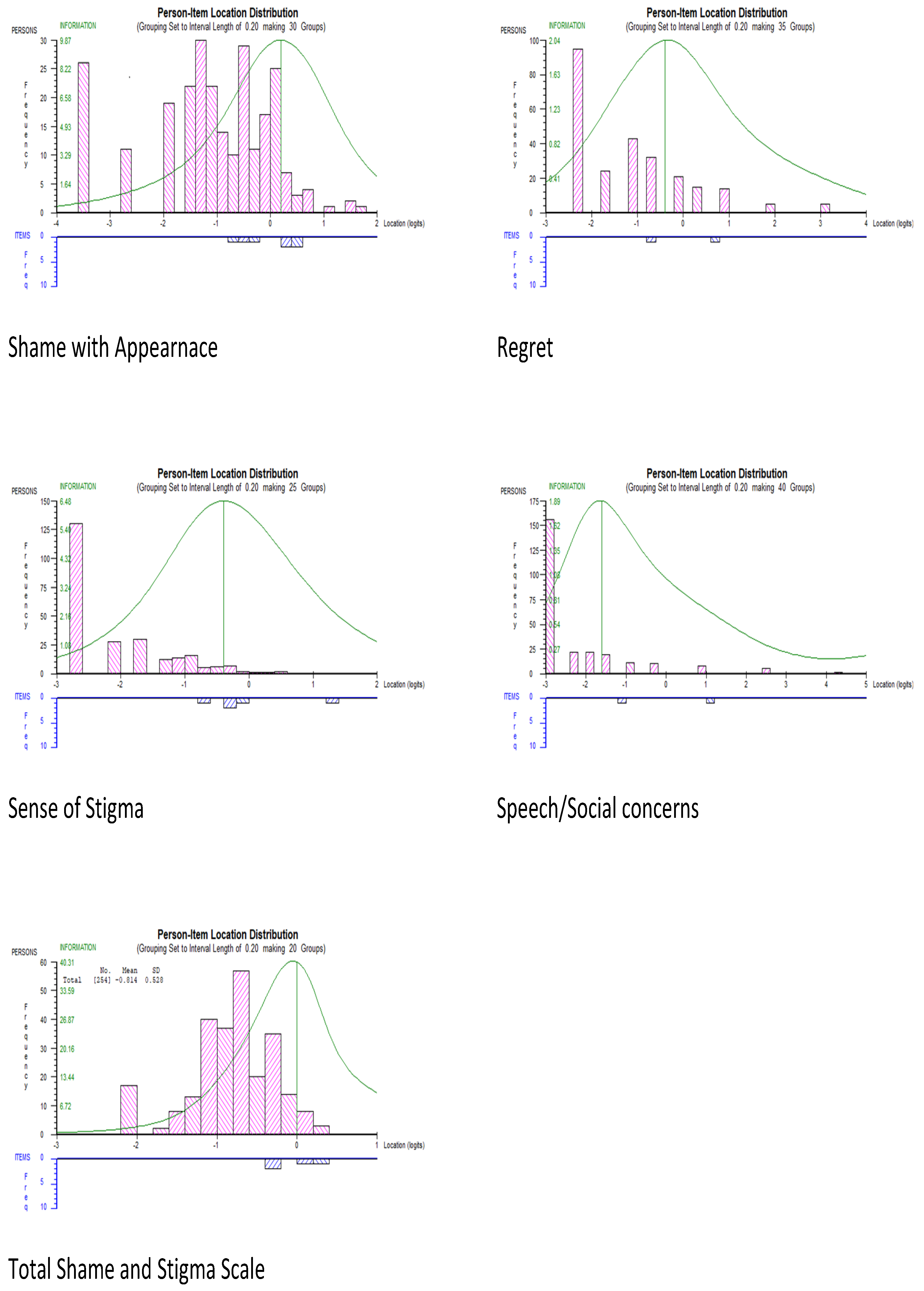

3.4. Rasch Analysis

4. Discussion

Strengths and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Never | Seldom | Sometimes | Often | All the Time | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. I like my appearance | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 2. I avoid looking at myself in the mirror | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 3. I am ashamed of my appearance | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 4. I am happy with how my face or neck looks | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 5. I feel people stare at me | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 6. I avoid meeting people because of my looks | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 7. I enjoy going out in public | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 8. I am embarrassed when I tell people my diagnosis | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 9. I feel ashamed for having developed cancer | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 10. People avoid me because of my cancer | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 11. I have an urge to keep my cancer a secret | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 12. I sense that others feel strained when around me | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 13. I have a strong feeling of regret | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 14. I would do many things differently if given a second chance | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 15. I am embarrassed by the change in my voice | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 16. I avoid talking with others | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

References

- Adams, R.J.; Wu, M.L.; Wilson, M. The Rasch rating model and the disordered threshold controversy. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 2012, 72, 547–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alias, A.; Henry, M. Psychosocial effects of head and neck cancer. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. Clin. N. Am. 2018, 30, 499–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andrich, D.; Sheridan, B.; Luo, G. RUMM2030 Software and Manuals; University of Western Australia: Perth, Australia, 2011; Available online: http://www.rummlab.com.au (accessed on 8 February 2023).

- Bjelland, I.; Dahl, A.A.; Haug, T.T.; Neckelmann, D. The validity of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale: An updated literature review. J. Psychosom. Res. 2002, 52, 69–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bjordal, K.; Kaasa, S. Psychological distress in head and neck cancer patients 7–11 years after curative treatment. Br. J. Cancer 1995, 71, 592–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bond, T.G.; Fox, C.M. Applying the Rasch Model: Fundamental Measurement in the Human Sciences; Psychology Press: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Buss, A.H.; Perry, M. The aggression questionnaire. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1992, 63, 452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cai, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Cao, W.; Hou, F.; Xin, M.; Guo, V.Y.; Deng, Y.; Wang, S.; You, X.; Li, J. Preliminary validation of the Chinese version of the Shame and Stigma Scale among patients with facial disfigurement from nasopharyngeal carcinoma. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0279290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cash, T.F.; Santos, M.T.; Williams, E.F. Coping with body-image threats and challenges: Validation of the Body Image Coping Strategies Inventory. J. Psychosom. Res. 2005, 58, 190–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cella, D.F.; Tulsky, D.S.; Gray, G.; Sarafian, B.; Linn, E.; Bonomi, A.; Silberman, M.; Yellen, S.B.; Winicour, P.; Brannon, J. The Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy scale: Development and validation of the general measure. J. Clin. Oncol. 1993, 11, 570–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Graeff, A.; De Leeuw, J.; Ros, W.; Hordijk, G.; Blijham, G.; Winnubst, J. A prospective study on quality of life of patients with cancer of the oral cavity or oropharynx treated with surgery with or without radiotherapy. Oral Oncol. 1999, 35, 27–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dearing, R.L.; Stuewig, J.; Tangney, J.P. On the importance of distinguishing shame from guilt: Relations to problematic alcohol and drug use. Addict. Behav. 2005, 30, 1392–1404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devins, G.M. Using the illness intrusiveness ratings scale to understand health-related quality of life in chronic disease. J. Psychosom. Res. 2010, 68, 591–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devins, G.M.; Binik, Y.M.; Hutchinson, T.A.; Hollomby, D.J.; Barré, P.E.; Guttmann, R.D. The emotional impact of end-stage renal disease: Importance of patients’ perceptions of intrusiveness and control. Int. J. Psychiatry Med. 1984, 13, 327–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diamond, P.M.; Magaletta, P.R. The short-form Buss-Perry Aggression questionnaire (BPAQ-SF) a validation study with federal offenders. Assessment 2006, 13, 227–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dropkin, M.J. Anxiety, coping strategies, and coping behaviors in patients undergoing head and neck cancer surgery. Cancer Nurs. 2001, 24, 143–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellis, M.A.; Sterba, K.R.; Brennan, E.A.; Maurer, S.; Hill, E.G.; Day, T.A.; Graboyes, E.M. A systematic review of patient-reported outcome measures assessing body image disturbance in patients with head and neck cancer. Otolaryngol. -Head Neck Surg. 2019, 160, 941–954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, D.G.; Fick, C. Measuring social desirability: Short forms of the Marlowe-Crowne social desirability scale. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 1993, 53, 417–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flora, D.B.; Curran, P.J. An empirical evaluation of alternative methods of estimation for confirmatory factor analysis with ordinal data. Psychol. Methods 2004, 9, 466–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gamba, A.; Romano, M.; Grosso, L.M.; Tamburini, M.; Cantú, G.; Molinari, R.; Ventafridda, V. Psychosocial adjustment of patients surgically treated for head and neck cancer. Head Neck 1992, 14, 218–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goffman, E. Stigma: Notes on the Management of Spoiled Identity; Simon and Schuster: New York, NY, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez, B.D.; Jacobsen, P.B. Depression in lung cancer patients: The role of perceived stigma. Psycho-Oncol. 2012, 21, 239–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goyal, A.K.; Bakshi, J.; Panda, N.K.; Kapoor, R.; Vir, D.; Kumar, K.; Aneja, P. Assessment of Shame and Stigma in Head and Neck Cancer: A Meta-Analysis. J. Maxillofac. Oral Surg. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henry, M.; Albert, J.G.; Frenkiel, S.; Hier, M.; Zeitouni, A.; Kost, K.; Mlynarek, A.; Black, M.; MacDonald, C.; Richardson, K.; et al. Body image concerns in patients with head and neck cancer: A longitudinal study. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 816587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hopwood, P.; Fletcher, I.; Lee, A.; Al Ghazal, S. A body image scale for use with cancer patients. Eur. J. Cancer 2001, 37, 189–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kissane, D.W.; Patel, S.G.; Baser, R.E.; Bell, R.; Farberov, M.; Ostroff, J.S.; Li, Y.; Singh, B.; Kraus, D.H.; Shah, J.P. Preliminary evaluation of the reliability and validity of the Shame and Stigma Scale in head and neck cancer. Head Neck 2012, 35, 172–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, H.B. Shame and guilt in neurosis. Psychoanal. Rev. 1971, 58, 419–438. [Google Scholar]

- Linacre, J.M. Sample Size and Item Calibration Stability. Rasch Meas. Trans. 1994, 7, 328. Available online: http://www.rasch.org/rmt/rmt74m.htm (accessed on 8 February 2023).

- Linacre, J.M. Optimizing rating scale category effectiveness. J. Appl. Meas. 2002, 3, 85–106. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Linacre, J.M. Rasch model estimation: Further topics. J. Appl. Meas. 2004, 5, 95–110. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- List, M.A.; D’Antonio, L.L.; Cella, D.F.; Siston, A.; Mumby, P.; Haraf, D.; Vokes, E. The performance status scale for head and neck cancer patients and the functional assessment of cancer therapy-head and neck scale: A study of utility and validity. Cancer 1996, 77, 2294–2301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marais, I.; Andrich, D. Formalizing dimension and response violations of local independence in the unidimensional Rasch model. J. Appl. Meas. 2008, 9, 200–215. [Google Scholar]

- Masters, G.N. A Rasch model for partial credit scoring. Psychometrika 1982, 47, 149–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melissant, H.C.; Jansen, F.; Eerenstein, S.; Cuijpers, P.; Laan, E.; Lissenberg-Witte, B.I.; Schuit, A.S.; Sherman, K.A.; Leemans, C.R.; Verdonck-de Leeuw, I.M. Body image distress in head and neck cancer patients: What are we looking at? Support. Care Cancer 2021, 29, 2161–2169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostroff, J.S.; Jacobsen, P.B.; Moadel, A.B.; Spiro, R.H.; Shah, J.P.; Strong, E.W.; Kraus, D.H.; Schantz, S.P. Prevalence and predictors of continued tobacco use after treatment of patients with head and neck cancer. Cancer 1995, 75, 569–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pallant, J.F.; Tennant, A. An introduction to the Rasch measurement model: An example using the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS). Br. J. Clin. Psychol. 2007, 46, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pruyn, J.; De Jong, P.; Bosman, L.; Van Poppel, J.; van Den Borne, H.; Ryckman, R.; De Meij, K. Psychosocial aspects of head and neck cancer–a review of the literature. Clin. Otolaryngol. Allied Sci. 1986, 11, 469–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Radloff, L.S. The CES-D scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Appl. Psychol. Meas. 1977, 1, 385–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasch, G. Probabilistic Models for Some Intelligence and Achievement Tests; Danish Institute for Educational Research: Copenhagen, Denmark, 1960. [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds, W.M. Development of reliable and valid short forms of the Marlowe-Crowne Social Desirability Scale. J. Clin. Psychol. 1982, 38, 119–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhoten, B.A.; Murphy, B.; Ridner, S.H. Body image in patients with head and neck cancer: A review of the literature. Oral Oncol. 2013, 49, 753–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez, A.M.; Frenkiel, S.; Desroches, J.; De Simone, A.; Chiocchio, F.; MacDonald, C.; Black, M.; Zeitouni, A.; Hier, M.; Kost, K.; et al. Development and validation of the McGill body image concerns scale for use in head and neck oncology (MBIS-HNC): A mixed-methods approach. Psycho-Oncol. 2019, 28, 116–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shunmuga Sundaram, C.; Dhillon, H.M.; Butow, P.N.; Sundaresan, P.; Rutherford, C. A systematic review of body image measures for people diagnosed with head and neck cancer (HNC). Support. Care Cancer 2019, 27, 3657–3666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- StataCorp. Stata Statistical Software: Release 17; StataCorp LLC: College Station, TX, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Tam, T. Addressing Stigma: Towards a More Inclusive Health System; Public Health Agency of Canada: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2019; Available online: https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/corporate/publications/chief-public-health-officer-reports-state-public-health-canada/addressing-stigma-toward-more-inclusive-health-system.html (accessed on 8 February 2023).

- Tennant, A.; Conaghan, P.G. The Rasch measurement model in rheumatology: What is it and why use it? When should it be applied, and what should one look for in a Rasch paper? Arthritis Care Res. 2007, 57, 1358–1362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tseng, W.-T.; Lee, Y.; Hung, C.-F.; Lin, P.-Y.; Chien, C.-Y.; Chuang, H.-C.; Fang, F.-M.; Li, S.-H.; Huang, T.-L.; Chong, M.-Y. Validation of the Chinese Version of the Shame and Stigma Scale in Patients with Head and Neck Cancer. Cancer Manag. Res. 2019, 11, 10297–10305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vallerand, R.J. Vers une méthodologie de validation trans-culturelle de questionnaires psychologiques: Implications pour la recherche en langue française. Can. Psychol./Psychol. Can. 1989, 30, 662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Azman, N.; Eyu, H.T.; Jaafar, N.R.N.; Sahimi, H.M.S.; Yunus, M.R.M.; Shariff, N.M.; Hami, R.; Mansor, N.S.; Lu, P.; et al. Validation of the Malay Version of the Shame and Stigma Scale among Cancer Patients in Malaysia. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 14266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zigmond, A.S.; Snaith, R.P. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 1983, 67, 361–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Items | Factor 1 Sense of Stigma | Factor 2 Shame with Appearance | Factor 3 Regret | Factor 4 Social/Speech Concerns |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. I like my appearance | 0.63 | 0.71 | ||

| 2. I avoid looking at myself in the mirror | 0.45 | 0.41 | ||

| 3. I am ashamed of my appearance | 0.49 | |||

| 4. I am happy with how my face or neck looks | 0.74 | |||

| 5. I feel people stare at me | 0.52 | |||

| 6. I avoid meeting people because of my looks | 0.51 | 0.50 | ||

| 7. I enjoy going out in public | 0.57 | |||

| 8. I am distressed by the changes in my face or neck | 0.57 | |||

| 9. I feel others consider me responsible for my cancer | 0.44 | |||

| 10. I am embarrassed when I tell people my diagnosis | 0.68 | |||

| 11. I feel ashamed for having developed cancer | 0.55 | |||

| 12. People avoid me because of my cancer | 0.41 | 0.49 | ||

| 13. I have an urge to keep my cancer a secret | 0.74 | |||

| 14. I sense that others feel strained when around me | 0.35 | 0.35 | ||

| 15. I have a strong feeling of regret | 0.64 | |||

| 16. I would do many things differently if given a second chance | 0.78 | |||

| 17. I feel sorry about things I have done in the past | 0.75 | |||

| 18. I am embarrassed by the change in my voice | 0.77 | |||

| 19. I avoid talking with others | 0.66 | |||

| 20. I am able to join conversations | 0.42 |

| No. of Items | % with 0 Scores | Max. Possible Score | Median (IQR) | Mean (SD) | Cronbach’s α | Test–Retest (Spearman’s Rho) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Shame with Appearance | 8 | 10.5% | 32 | 6.0 (3.0–11.0) | 7.5 (6.2) | 0.82 | 0.68 * |

| Sense of Stigma | 6 | 47.2% | 24 | 1.0 (0.0–4.0) | 2.3 (3.4) | 0.76 | 0.73 * |

| Regret | 3 | 28.0% | 12 | 3.0 (0.0–5.0) | 3.2 (3.0) | 0.79 | 0.60 * |

| Social/Speech Concerns | 3 | 35.1% | 12 | 2.0 (0.0–4.0) | 2.6 (2.6) | 0.52 | 0.57 * |

| Total Scale | 20 | 2.9% | 80 | 12.0 (6.0–22.0) | 15.4 (11.9) | 0.88 | 0.72 * |

| Item | % with 0 Scores | % Scoring ≥ 3 | Corrected Correlation with Total Scale | Corrected Correlation with Subscale |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Shame with Appearance | ||||

| 1. I like my appearance | 25.5 | 17.6 | 0.61 | 0.71 |

| 2. I avoid looking at myself in the mirror | 63.9 | 9.8 | 0.56 | 0.65 |

| 3. I am ashamed of my appearance | 69.0 | 5.1 | 0.60 | 0.66 |

| 4. I am happy with how my face or neck looks | 26.1 | 29.3 | 0.56 | 0.69 |

| 5. I feel people stare at me | 56.3 | 11.4 | 0.59 | 0.65 |

| 6. I avoid meeting people because of my looks | 75.0 | 3.1 | 0.66 | 0.69 |

| 7. I enjoy going out in public | 41.0 | 19.9 | 0.56 | 0.64 |

| 8. I am distressed by the changes in my face or neck | 64.1 | 7.0 | 0.62 | 0.71 |

| Sense of Stigma | ||||

| 9. I feel others consider me responsible for my cancer | 79.7 | 4.3 | 0.49 | 0.57 |

| 10. I am embarrassed when I tell people my diagnosis | 76.2 | 3.9 | 0.61 | 0.81 |

| 11. I feel ashamed for having developed cancer | 79.4 | 4.0 | 0.59 | 0.75 |

| 12. People avoid me because of my cancer | 86.5 | 3.6 | 0.52 | 0.59 |

| 13. I have an urge to keep my cancer a secret | 74.4 | 6.7 | 0.46 | 0.67 |

| 14. I sense that others feel strained when around me | 71.6 | 3.2 | 0.63 | 0.69 |

| Regret | ||||

| 15. I have a strong feeling of regret | 62.6 | 8.7 | 0.68 | 0.81 |

| 16. I would do many things differently if given a second chance | 40.9 | 22.5 | 0.57 | 0.88 |

| 17. I feel sorry about things I have done in the past | 40.6 | 12.6 | 0.55 | 0.83 |

| Social/Speech Concerns | ||||

| 18. I am embarrassed by the change in my voice | 69.8 | 12.3 | 0.57 | 0.77 |

| 19. I avoid talking with others | 70.6 | 4.0 | 0.71 | 0.74 |

| 20. I am able to join conversations | 43.9 | 21.7 | 0.24 | 0.69 |

| BICSI Appearance Fixing | BICSI Avoidance | BIS | HADS Depression | HADS Anxiety | CES-D | IIRS | FACT-G | FACT H&N | BPAQ | MCSD | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Shame with Appearance | 0.54 | 0.51 | 0.63 | 0.54 | 0.52 | 0.52 | 0.45 | −0.65 | −0.52 | 0.28 | −0.32 |

| Sense of Stigma | 0.48 | 0.48 | 0.50 | 0.41 | 0.48 | 0.43 | 0.45 | −0.42 | −0.42 | 0.36 | −0.33 |

| Regret | 0.43 | 0.36 | 0.42 | 0.43 | 0.41 | 0.37 | 0.41 | −0.40 | −0.41 | 0.32 | −0.32 |

| Social/Speech Concerns | 0.23 | 0.26 | 0.37 | 0.39 | 0.32 | 0.39 | 0.30 | −0.50 | −0.50 | 0.18 | −0.15 |

| Total Scale | 0.58 | 0.55 | 0.66 | 0.57 | 0.60 | 0.58 | 0.52 | −0.69 | −0.61 | 0.35 | −0.36 |

| Analysis | Item Residual Mean (SD) | Person Residual Mean (SD) | χ2 | p | PSI | α | Unidimensionality % Significant t-Tests (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Shame with Appearance (8 items) DIF for item 5 and item 8 for language. | 0.80 (1.01) | −1.14 (1.15) | 21.37 | 0.165 | 0.73 | 0.82 | 7.09 (4.41–9.76) |

| Final (7 items): Item 8 removed due to DIF. No remining DIF for any items after item 8 removed. | 0.98 (0.62) | −0.37 (1.10) | 28.08 | 0.014 | 0.72 | 0.79 | 7.48 (4.79–10.16) |

| Sense of Stigma (6 items) | −0.29(0.98) | −1.88 (0.80) | 19.85 | 0.003 * | 0.21 | 0.76 | 0 |

| Final (5 items): Item 9 not included due to model misfit and not loading on appropriate factor. | −0.14 (0.74) | −0.32 (1.08) | 12.41 | 0.03 | 0.22 | 0.77 | 0 |

| Regret (3 items) | 0.35 (0.76) | −0.40 (0.97) | 4.36 | 0.225 | 0.56 | 0.79 | 0.79 (−1.89–3.46) |

| Final (2 items): Item 17 deleted due to DIF | 0.36(0.55) | −0.50 (1.06) | 5.03 | 0.081 | 0.37 | 0.71 | 0 |

| Social/Speech Concerns (3 items) Misfit in item 20. | 0.73 (1.44) | −0.11 (0.90) | 93.24 | 0.000 * | −0.16 | 0.52 | 0.39 (−2.29–3.07) |

| Final (2 items): Item 20 removed | 0.63 (1.04) | −0.29 (0.82) | 4.92 | 0.085 | 0.48 | 0.79 | 0.39 (−2.29–3.07) |

| Total Scale (16 items) (With four subscales and items 8, 9, 17, 20 deleted) | −0.47 (1.27) | −0.32 (0.82) | 25.55 | 0.012 | 0.62 | 0.70 | 2.36 (−0.318–5.04) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bobevski, I.; Kissane, D.W.; Desroches, J.; De Simone, A.; Henry, M. Validation of the Canadian Version of the Shame and Stigma Scale for Head and Neck Cancer Patients. Curr. Oncol. 2023, 30, 7553-7565. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol30080548

Bobevski I, Kissane DW, Desroches J, De Simone A, Henry M. Validation of the Canadian Version of the Shame and Stigma Scale for Head and Neck Cancer Patients. Current Oncology. 2023; 30(8):7553-7565. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol30080548

Chicago/Turabian StyleBobevski, Irene, David W. Kissane, Justin Desroches, Avina De Simone, and Melissa Henry. 2023. "Validation of the Canadian Version of the Shame and Stigma Scale for Head and Neck Cancer Patients" Current Oncology 30, no. 8: 7553-7565. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol30080548

APA StyleBobevski, I., Kissane, D. W., Desroches, J., De Simone, A., & Henry, M. (2023). Validation of the Canadian Version of the Shame and Stigma Scale for Head and Neck Cancer Patients. Current Oncology, 30(8), 7553-7565. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol30080548