Management of Very Early Small Cell Lung Cancer: A Canadian Survey Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

4. Discussion

- Multidisciplinary discussion is important in cases where prospective evidence is limited. These cases should be discussed at multidisciplinary tumour boards to determine the most appropriate management strategy for each individual patient, based on their unique characteristics and care goals of care.

- Invasive mediastinal staging should be performed prior to deciding on a treatment strategy [9], as occult nodal disease is not uncommon in SCLC. Studies have shown that among patients who underwent surgery, those who had four or more lymph nodes removed had better outcomes than those with fewer than four nodes removed, likely due to more accurate staging prior to treatment [14].

- Surgery followed by adjuvant chemotherapy is a viable approach for medically operable patients, particularly for T1 lesions, as recommended by guidelines [9,11]. However, caution should be exercised for larger lesions. On subgroup analysis in one study evaluating the benefit of surgery for SCLC, T2 lesions had poorer survival and higher unresectability rates than T1 lesions [15].

- For patients who are not medically operable, SBRT followed by adjuvant chemotherapy may be considered [16]. The evidence for this recommendation is not strong, based on a few small retrospective studies. The largest of these, published by Verma et al., included 74 patients and showed overall survival rates comparable to those in previously published surgical series [17]. However, outcomes were worse with tumours larger than 2 cm, indicating that this approach is best suited for smaller (T1) lesions.

- MRI surveillance is a reasonable alternative to prophylactic cranial irradiation (PCI) in this population. The original meta-analysis regarding PCI in patients with SCLC [18] included older studies with less accurate staging. As a result, patients included were at higher risk, with over 10% having extensive-stage disease. In a retrospective review of patients with SCLC who underwent resection, PCI had survival benefits for stage II and stage III disease but not for stage I disease [19]. Given the relatively lower risk of brain metastasis in this population and the neurotoxic effects of cranial irradiation, the risk likely outweighs the benefit.

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

- 1

- What is your specialty?

- a

- Medical Oncologist

- b

- Radiation Oncologist

- c

- Other

- 2

- What percentage of your practice involves lung cancer patients?

- a

- Less than 25%

- b

- 25–50%

- c

- More than 50%

- 3

- Which region of the country do you practice in?

- a

- Eastern Canada (NB, PE, NS, NL)

- b

- Quebec

- c

- Ontario

- d

- Western Canada (BC, AB, SK, MB)

- 4

- What is the nature of your practice?

- a

- Majority (>50%) academic

- b

- Majority (>50%) community

- 5

- How long have you been in practice?

- a

- Less than 5 years

- b

- 5–10 years

- c

- 11–20 years

- d

- More than 20 years

- 6

- If you are a Medical Oncologist, does your centre have Radiation Oncology services?

- a

- Yes

- b

- No

- 1

- What is your usual recommendation for treating early limited-stage SCLC?

- a

- Chemoradiation

- b

- Surgery alone

- c

- Surgery followed by adjuvant chemotherapy

- d

- SBRT alone

- e

- SBRT followed by adjuvant chemotherapy

- f

- No standard, depends on the case

- 2

- Does your centre have an institutional policy regarding management of these cases?

- a

- Yes

- b

- No

- 3

- Are you aware of any guidelines regarding management of these cases?

- a

- Yes

- b

- No

- 4

- If yes, please indicate the guideline: ______________

- 5

- Approximately what proportion of your SCLC cases are these early (T1 or T2, N0) cases?

- a

- Less than 10%

- b

- 10–30%

- c

- 30–50%

- d

- Greater than 50%

- 6

- Do these patients get discussed at tumour boards?

- a

- Always or almost always

- b

- Sometimes

- c

- Rarely or never

- 7

- Do you pursue invasive mediastinal staging in these cases, if not already done?

- a

- Always or almost always

- b

- Sometimes

- c

- Rarely or never

- 8

- Does the size of the tumour (T1 vs. T2) influence how you manage these cases?

- a

- Yes

- b

- No

- 9

- If you offer SBRT, what fractionation do you use?

- a

- Same fractionation as NSCLC cases

- b

- Different fractionation than NSCLC cases

- 10

- Do you routinely offer these patients prophylactic cranial irradiation (PCI)?

- a

- Always or almost always

- b

- Sometimes

- c

- Rarely or never

- 11

- Do you routinely offer these patients chemotherapy in addition to local therapy, assuming no contraindications to systemic therapy?

- a

- Always or almost always

- b

- Sometimes

- c

- Rarely or never

- 1

- Would you recommend/pursue invasive mediastinal staging?

- a

- Yes

- b

- No

- 2

- The patient was seen by a surgeon and deemed to be medically operable. What is your recommended management?

- a

- Concurrent chemoradiation

- b

- Surgery alone

- c

- Surgery followed by adjuvant chemotherapy

- d

- SBRT alone

- e

- SBRT followed by adjuvant chemotherapy

- 3

- The patient was seen by a surgeon and was deemed medically inoperable. What is your recommended management?

- a

- Concurrent chemoradiation

- b

- SBRT alone

- c

- SBRT followed by adjuvant chemotherapy

- 4

- Would you offer the patient prophylactic cranial irradiation (PCI)?

- a

- Yes

- b

- No

- 1

- Would you recommend/pursue invasive mediastinal staging?

- a

- Yes

- b

- No

- 2

- The patient was seen by a surgeon and deemed to be medically operable. What is your recommended management?

- a

- Concurrent chemoradiation

- b

- Surgery alone

- c

- Surgery followed by adjuvant chemotherapy

- d

- SBRT alone

- e

- SBRT followed by adjuvant chemotherapy

- 3

- The patient was seen by a surgeon and was deemed medically inoperable. What is your recommended management?

- a

- Concurrent chemoradiation

- b

- SBRT alone

- c

- SBRT followed by adjuvant chemotherapy

- 4

- Would you offer the patient prophylactic cranial irradiation (PCI)?

- a

- Yes

- b

- No

- 1

- Would you recommend/pursue invasive mediastinal staging?

- a

- Yes

- b

- No

- 2

- The patient was seen by a surgeon and deemed to be medically operable. What is your recommended management?

- a

- Concurrent chemoradiation

- b

- Surgery alone

- c

- Surgery followed by adjuvant chemotherapy

- d

- SBRT alone

- e

- SBRT followed by adjuvant chemotherapy

- 3

- The patient was seen by a surgeon and was deemed medically inoperable. What is your recommended management?

- a

- Concurrent chemoradiation

- b

- SBRT alone

- c

- SBRT followed by adjuvant chemotherapy

- 4

- Would you offer the patient prophylactic cranial irradiation (PCI)?

- a

- Yes

- b

- No

References

- Canadian Cancer Society. Lung and Bronchus Cancer Statistics. 2023. Available online: https://cancer.ca/en/cancer-information/cancer-types/lung/statistics (accessed on 14 January 2023).

- Lung Cancer Canada. An Overview of Lung Cancer. 2023. Available online: https://www.lungcancercanada.ca/en-CA/Lung-Cancer.aspx (accessed on 14 January 2023).

- Micke, P.; Faldum, A.; Metz, T.; Beeh, K.M.; Bittinger, F.; Hengstler, J.G.; Buhl, R. Staging small cell lung cancer: Veterans Administration Lung Study Group versus International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer—What limits limited disease? Lung Cancer 2002, 37, 271–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Canadian Cancer Society. Survival Statistics for Small Cell Lung Cancer. 2023. Available online: https://cancer.ca/en/cancer-information/cancer-types/lung/prognosis-and-survival/small-cell-lung-cancer-survival-statistics (accessed on 14 January 2023).

- De Ruysscher, D.; Pijls-Johannesma, M.; Vansteenkiste, J.; Kester, A.; Rutten, I.; Lambin, P. Systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised, controlled trials of the timing of chest radiotherapy in patients with limited-stage, small-cell lung cancer. Ann. Oncol. 2006, 17, 543–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simone, C.B.; Bogart, J.A.; Cabrera, A.R.; Daly, M.E.; DeNunzio, N.J.; Detterbeck, F.; Faivre-Finn, C.; Gatschet, N.; Gore, E.; Jabbour, S.K.; et al. Radiation Therapy for Small Cell Lung Cancer: An ASTRO Clinical Practice Guideline. Pr. Radiat. Oncol. 2020, 10, 158–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sittenfeld, S.M.C.; Ward, M.C.; Tendulkar, R.D.; Videtic, G. Essentials of Clinical Radiation Oncology, 2nd ed.; Demos Medical: New York, NY, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Moreno, A.C.; Lin, S.H. The optimal treatment approaches for stage I small cell lung cancer. Transl. Lung Cancer Res. 2019, 8, 88–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ganti, A.K.P.; Loo, B.W.; Bassetti, M.; Blakely, C.; Chiang, A.; D’Amico, T.A.; D’Avella, C.; Dowlati, A.; Downey, R.J.; Edelman, M.; et al. Small Cell Lung Cancer, Version 2.2022, NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. J. Natl. Compr. Cancer Netw. 2021, 19, 1441–1464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stahl, J.M.; Corso, C.D.; Verma, V.; Park, H.S.; Nath, S.K.; Husain, Z.A.; Simone, C.B.; Kim, A.W.; Decker, R.H. Trends in stereotactic body radiation therapy for stage I small cell lung cancer. Lung Cancer 2017, 103, 11–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Früh, M.; De Ruysscher, D.; Popat, S.; Crinò, L.; Peters, S.; Felip, E.; ESMO Guidelines Working Group. Small-cell lung cancer (SCLC): ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann. Oncol. 2013, 24 (Suppl. 6), vi99–vi105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, A.; Durocher-Allen, L.; Ellis, P.; Ung, Y.; Goffin, J.; Ramchandar, K.; Darling, G. Guideline for the Initial Management of Small Cell Lung Cancer (Limited and Extensive Stage) and the Role of Thoracic Radiotherapy and First-line Chemotherapy. Clin. Oncol. 2018, 30, 658–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alberta Health Services. Clinical Practice Guideline. Small Cell Lung Cancer: Limited Stage. 2012. Available online: https://www.albertahealthservices.ca/assets/info/hp/cancer/if-hp-cancer-guide-lu006-lcsc-ltd-stage.pdf (accessed on 14 January 2023).

- Ahmed, Z.; Kujtan, L.; Kennedy, K.F.; Davis, J.R.; Subramanian, J. Disparities in the Management of Patients with Stage I Small Cell Lung Carcinoma (SCLC): A Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) Analysis. Clin. Lung Cancer 2017, 18, e315–e325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lad, T.; Piantadosi, S.; Thomas, P.; Payne, D.; Ruckdeschel, J.; Giaccone, G. A Prospective Randomized Trial to Determine the Benefit of Surgical Resection of Residual Disease Following Response of Small Cell Lung Cancer to Combination Chemotherapy. Chest 1994, 106, 320S–323S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Safavi, A.H.; Mak, D.Y.; Boldt, R.G.; Chen, H.; Louie, A.V. Stereotactic ablative radiotherapy in T1-2N0M0 small cell lung cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Lung Cancer 2021, 160, 179–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verma, V.; Simone, C.B.; Allen, P.K.; Gajjar, S.R.; Shah, C.; Zhen, W.; Harkenrider, M.M.; Hallemeier, C.L.; Jabbour, S.K.; Matthiesen, C.L.; et al. Multi-Institutional Experience of Stereotactic Ablative Radiation Therapy for Stage I Small Cell Lung Cancer. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 2017, 97, 362–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aupérin, A.; Arriagada, R.; Pignon, J.P.; Le Péchoux, C.; Gregor, A.; Stephens, R.J.; Kristjansen, P.E.; Johnson, B.E.; Ueoka, H.; Wagner, H.; et al. Prophylactic Cranial Irradiation for Patients with Small-Cell Lung Cancer in Complete Remission. Prophylactic Cranial Irradiation Overview Collaborative Group. N. Engl. J. Med. 1999, 341, 476–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, J.; Yang, H.; Fu, X.; Jin, B.; Lou, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, X.; Zhong, H.; Wang, H.; Wu, D.; et al. Prophylactic Cranial Irradiation for Patients with Surgically Resected Small Cell Lung Cancer. J. Thorac. Oncol. 2017, 12, 347–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Specialty (n = 77) | |

| Medical oncologist | 30 (39%) |

| Radiation oncologist | 46 (60%) |

| Other | 1 (1%) |

| Percentage of practice involving lung cancer patients (n = 77) | |

| <25% | 16 (21%) |

| 25–50% | 28 (36%) |

| >50% | 33 (43%) |

| Region of practice (n = 76) | |

| Eastern Canada (NB, NS, NL, PE) | 7 (9%) |

| Quebec (QC) | 22 (29%) |

| Ontario (ON) | 23 (30%) |

| Western Canada (BC, AB, SK, MB) | 24 (32%) |

| Nature of practice (n = 77) | |

| Majority (>50%) academic | 53 (69%) |

| Majority (>50%) community | 24 (31%) |

| Length of time in practice (n = 77) | |

| <5 years | 12 (16%) |

| 5–10 years | 19 (25%) |

| 11–20 years | 24 (31%) |

| >20 years | 22 (29%) |

| Presence of institutional policy regarding optimal management of this group (n = 76) | |

| Yes | 8 (11%) |

| No | 68 (89%) |

| Awareness of guidelines regarding optimal management of this group (n = 75) | |

| Yes | 24 (32%) |

| No | 51 (68%) |

| Are these patients discussed at tumour boards? (n = 76) | |

| Always or almost always | 41 (54%) |

| Sometimes | 29 (38%) |

| Rarely or never | 6 (8%) |

| Usual recommendation for management (n = 76) | |

| Concurrent chemoradiation | 23 (30%) |

| Surgery alone | 2 (3%) |

| Surgery with adjuvant chemotherapy | 29 (38%) |

| SBRT alone | 0 (0%) |

| SBRT with adjuvant chemotherapy | 3 (4%) |

| No standard, depends on the case | 19 (25%) |

| Does the size of the lesion (T1 vs. T2) affect your recommendation? (n = 75) | |

| Yes | 38 (51%) |

| No | 37 (49%) |

| Do you pursue invasive mediastinal staging? (n = 74) | |

| Always or almost always | 33 (45%) |

| Sometimes | 32 (43%) |

| Rarely or never | 9 (12%) |

| Do you offer prophylactic cranial irradiation? (n = 48) | |

| Always or almost always | 16 (33%) |

| Sometimes | 19 (40%) |

| Rarely or never | 13 (27%) |

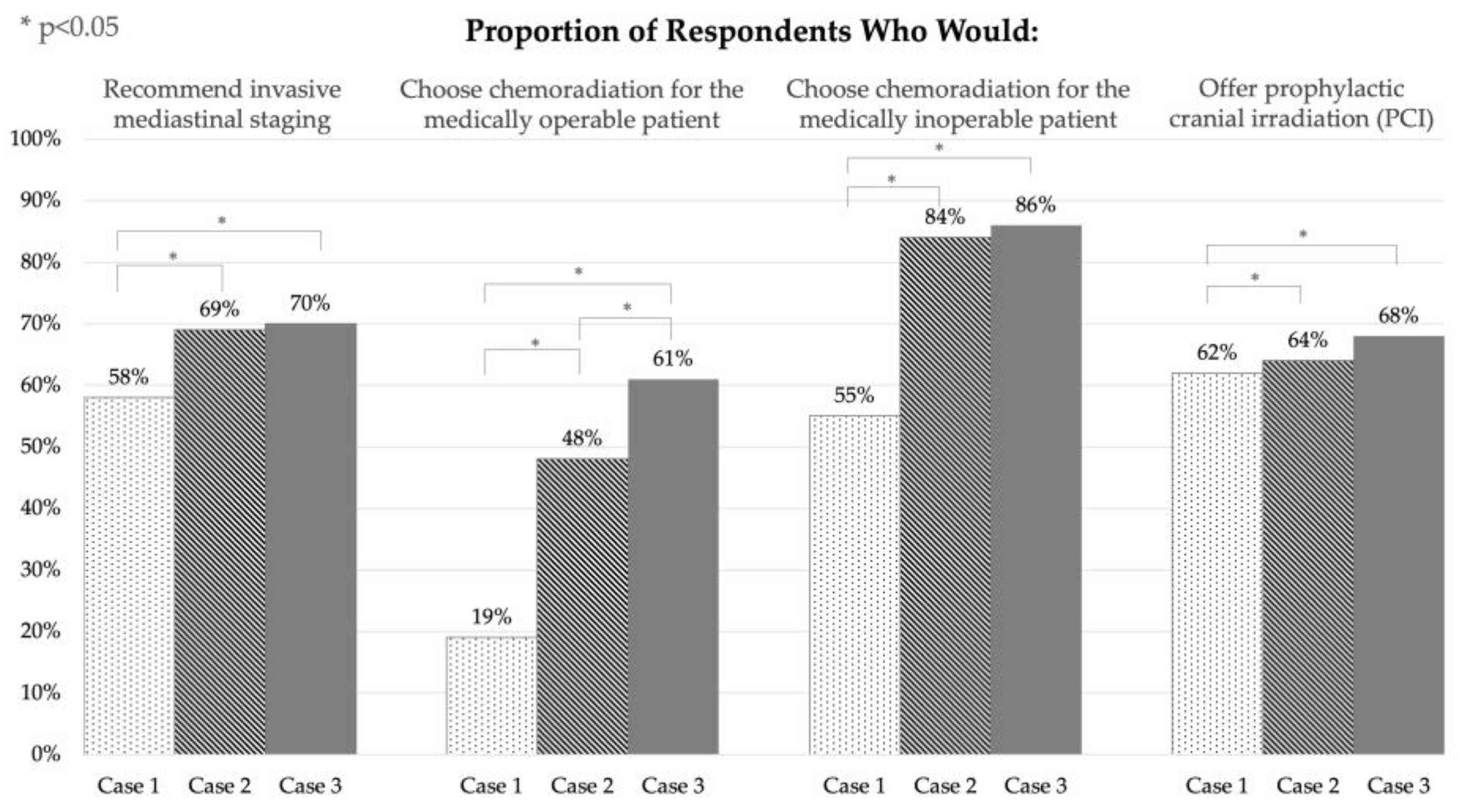

| Would you recommend/pursue invasive mediastinal staging? | |||

| Case 1—peripheral T1 (2 cm) lesion (n = 74) | Case 2—central T1 (2 cm) lesion (n = 74) | Case 3—peripheral T2 (4.5 cm) lesion (n = 74) | |

| Yes | 43 (58%) | 51 (69%) | 52 (70%) |

| No | 31 (42%) | 23 (31%) | 22 (30%) |

| The patient was deemed to be medically operable. What is your recommended management? | |||

| Case 1—peripheral T1 (2 cm) lesion (n = 73) | Case 2—central T1 (2 cm) lesion (n = 73) | Case 3—peripheral T2 (4.5 cm) lesion (n = 74) | |

| Concurrent chemoradiation | 14 (19%) | 35 (48%) | 45 (61%) |

| Surgery alone | 3 (4%) | 2 (3%) | 1 (1%) |

| Surgery with adjuvant chemotherapy | 52 (73%) | 34 (47%) | 27 (36%) |

| SBRT alone | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

| SBRT with adjuvant chemotherapy | 3 (4%) | 2 (3%) | 1 (1%) |

| The patient was deemed to be medically inoperable. What is your recommended management? | |||

| Case 1—peripheral T1 (2 cm) lesion (n = 74) | Case 2—central T1 (2 cm) lesion (n = 74) | Case 3—peripheral T2 (4.5 cm) lesion (n = 73) | |

| Concurrent chemoradiation | 41 (55%) | 62 (84%) | 63 (86%) |

| SBRT alone | 1 (1%) | 1 (1%) | 0 (0%) |

| SBRT and adjuvant chemotherapy | 32 (43%) | 11 (15%) | 10 (14%) |

| Would you offer prophylactic cranial irradiation (PCI)? | |||

| Case 1—peripheral T1 (2 cm) lesion (n = 73) | Case 2—central T1 (2 cm) lesion (n = 74) | Case 3—peripheral T2 (4.5 cm) lesion (n = 72) | |

| Yes | 45 (62%) | 47 (64%) | 49 (68%) |

| No | 28 (38%) | 27 (36%) | 23 (32%) |

| Physician Subgroup | Proportion Who Chose Concurrent Chemoradiation for the Medically Operable Patient | Proportion Who Chose Concurrent Chemoradiation for the Medically Inoperable Patient | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Case 1 | Case 2 | Case 3 | Case 1 | Case 2 | Case 3 | |

| Specialty | ||||||

| Medical oncologists | 27% | 50% | 67% | 60% | 83% | 93% |

| Radiation oncologists | 14% | 48% | 56% | 51% | 84% | 81% |

| p-value | 0.1906 | 0.8420 | 0.3512 | 0.4554 | 1.0000 | 0.1776 |

| Percentage of practice lung cancer | ||||||

| <25% | 27% | 53% | 80% | 60% | 80% | 87% |

| 25–50% | 14% | 44% | 61% | 54% | 93% | 86% |

| >50% | 20% | 48% | 52% | 55% | 77% | 87% |

| p-value | 0.6101 | 0.8566 | 0.1810 | 0.9184 | 0.2455 | 1.0000 |

| Region of practice | ||||||

| Eastern (NB, NS, NL, PE) | 14% | 33% | 71% | 71% | 71% | 86% |

| Quebec (QC) | 5% | 45% | 60% | 60% | 90% | 85% |

| Ontario (ON) | 9% | 35% | 44% | 30% | 70% | 77% |

| Western (BC, AB, SK, MB) | 39% | 65% | 74% | 70% | 96% | 96% |

| p-value | 0.0206 * | 0.1731 | 0.2041 | 0.0360 * | 0.0598 | 0.3067 |

| Nature of practice | ||||||

| Majority (>50%) academic | 20% | 45% | 59% | 51% | 84% | 88% |

| Majority (>50%) community | 17% | 55% | 65% | 65% | 83% | 83% |

| p-value | 1.0000 | 0.4585 | 0.6020 | 0.2541 | 1.0000 | 0.7153 |

| Length of time in practice | ||||||

| <5 years | 0% | 30% | 40% | 20% | 70% | 60% |

| 5–10 years | 5% | 37% | 63% | 47% | 74% | 79% |

| 11–20 years | 30% | 58% | 67% | 63% | 88% | 92% |

| >20 years | 29% | 55% | 62% | 71% | 95% | 100% |

| p-value | 0.0456 * | 0.2999 | 0.5286 | 0.0413 * | 0.1413 | 0.0091 * |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Malakouti-Nejad, B.; Moore, S.; Wheatley-Price, P.; Tiberi, D. Management of Very Early Small Cell Lung Cancer: A Canadian Survey Study. Curr. Oncol. 2023, 30, 6006-6018. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol30070449

Malakouti-Nejad B, Moore S, Wheatley-Price P, Tiberi D. Management of Very Early Small Cell Lung Cancer: A Canadian Survey Study. Current Oncology. 2023; 30(7):6006-6018. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol30070449

Chicago/Turabian StyleMalakouti-Nejad, Bayan, Sara Moore, Paul Wheatley-Price, and David Tiberi. 2023. "Management of Very Early Small Cell Lung Cancer: A Canadian Survey Study" Current Oncology 30, no. 7: 6006-6018. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol30070449

APA StyleMalakouti-Nejad, B., Moore, S., Wheatley-Price, P., & Tiberi, D. (2023). Management of Very Early Small Cell Lung Cancer: A Canadian Survey Study. Current Oncology, 30(7), 6006-6018. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol30070449