Progress toward Health System Readiness for Genome-Based Testing in Canada

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Canada

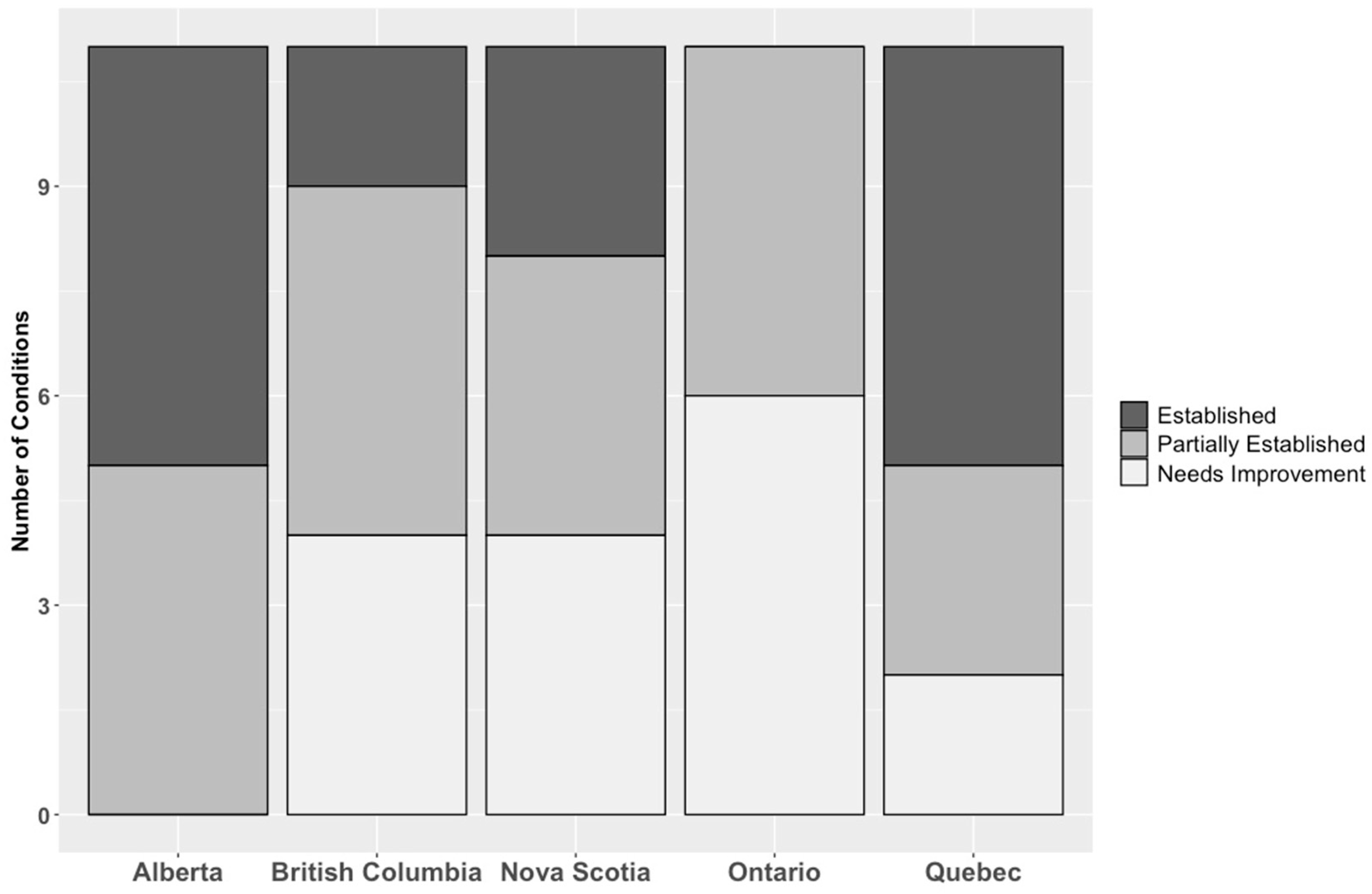

3.1.1. Alberta

- Established conditions—Alberta has established conditions related to resource planning, informatics, a single-entry point for innovation, a coordinated service model, the integration of innovation and healthcare delivery, and regulation.

- Partially established conditions—Alberta still requires broader engagement with stakeholders beyond care providers and patients; a more transparent evaluation function; improved tools for care navigation; a more comprehensive and transparent finance approach that considers the associated costs of development, capital infrastructure, and human resources; and province-wide standards for education and training.

- Conditions requiring significant improvement—none.

3.1.2. British Columbia (BC)

- Established conditions—British Columbia has established conditions related to resource planning and regulation.

- Partially established conditions—British Columbia still requires broader engagement with stakeholders beyond the clinical community, an open application process for innovation proposals, a more coordinated service model, further integration of innovation and healthcare delivery, and a more comprehensive finance approach.

- Conditions requiring significant improvement—British Columbia has yet to establish linked laboratory information systems, a transparent evaluation function, improved tools for care navigation, and province-wide standards for education and training.

3.1.3. Ontario

- Established conditions—Ontario has not yet fully established any of the necessary conditions required for health system readiness.

- Partially established conditions—Ontario still requires broader engagement with stakeholders beyond care providers and patients, ongoing resource planning, a more coordinated service model, better integration of innovation with mainstream healthcare delivery, and province-wide analytic standards (regulation).

- Conditions requiring improvement—Ontario has yet to establish linked laboratory information systems; create a single-entry point for innovation; a single, fit-for-purpose evaluation function; tools for care navigation; province-wide standards for education and training; and a more comprehensive finance approach. Some of these are currently being planned for development.

3.1.4. Nova Scotia

- Established conditions—Nova Scotia has established conditions related to resource planning, a coordinated service model, and the integration of innovation with mainstream healthcare delivery.

- Partially established conditions—Nova Scotia still requires broader engagement with innovation stakeholders, an improved financing approach, and province-wide analytic standards (regulation). Nova Scotia has taken some steps to aid care navigation (i.e., test directory and ongoing communication to providers), but not all tests (e.g., oncology) are listed.

- Conditions requiring improvement—Nova Scotia has yet to establish linked laboratory information systems; create a single-entry point for innovation; a single, fit-for-purpose evaluation function; and standards for education and training.

3.1.5. Quebec

- Established conditions—Through the DBBM, Quebec has established conditions related to resource planning, a more robust finance approach, and standards for analysis, accreditation, and proficiency (regulation). It also has an established evaluation function (with INESSS) and linked information systems.

- Partially established conditions—Quebec still requires broader engagement with stakeholders beyond care providers. While it has a single-entry point for innovation, it is closed to commercial innovators. It similarly lacks standards for education and training, but these are being developed. While it has created a coordinated service model, there are still further opportunities to improve the coordination and timing of testing.

- Conditions requiring improvement—Quebec still does not fully integrate investigational testing into mainstream care. Awareness and navigational tools for care providers and patients is lacking; not all available tests are published on its test list (‘repertoire’).

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Interview Guide

- It will help identify current challenges with the uptake and routine delivery of advanced diagnostic testing

- To explore what conditions are necessary and desirable for creating robust systems of advanced diagnostic testing (either in your region or generally)

- Do you feel the current testing services offered are sufficient to keep up with the current and future demand for advanced testing?

- What are the current challenges with the uptake and routine delivery of advanced diagnostic testing?

- Do you have any cases that exemplify these challenges?

- Do these challenges differ depending on whether testing is intended for diagnosis, therapeutic decisions, or hereditary testing?

- What do you feel needs to change in order to keep up with current/future demand and address these challenges?

- Who are the key decision makers, organizers and administrators of advanced testing that are currently involved?

- Who else needs to be involved?

- Are there any proposed changes currently?

- Do you have any further thoughts on what needs to change to support a more nimble approach to the awareness, acceptance, and adoption of advanced testing?

- Permission to Use Name, Interviewee demographics.

References

- Sikka, R.; Morath, J.M.; Leape, L. The Quadruple Aim: Care, Health, Cost and Meaning in Work. BMJ Qual. Saf. 2015, 24, 608–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ginsburg, G.S. Realizing the Opportunities of Genomics in Health Care. JAMA 2013, 309, 1463–1464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sperber, N.R.; Carpenter, J.S.; Cavallari, L.H.; Damschroder, L.J.; Cooper-DeHoff, R.M.; Denny, J.C.; Ginsburg, G.S.; Guan, Y.; Horowitz, C.R.; Levy, K.D.; et al. Challenges and Strategies for Implementing Genomic Services in Diverse Settings: Experiences from the Implementing GeNomics In PracTicE (IGNITE) Network. BMC Med. Genom. 2017, 10, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Skivington, K.; Matthews, L.; Simpson, S.A.; Craig, P.; Baird, J.; Blazeby, J.M.; Boyd, K.A.; Craig, N.; French, D.P.; McIntosh, E.; et al. A New Framework for Developing and Evaluating Complex Interventions: Update of Medical Research Council Guidance. BMJ 2021, 374, n2061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Husereau, D.; Steuten, L.; Muthu, V.; Thomas, D.M.; Spinner, D.S.; Ivany, C.; Mengel, M.; Sheffield, B.; Yip, S.; Jacobs, P.; et al. Effective and Efficient Delivery of Genome-Based Testing-What Conditions Are Necessary for Health System Readiness? Healthcare 2022, 10, 2086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mateo, J.; Steuten, L.; Aftimos, P.; André, F.; Davies, M.; Garralda, E.; Geissler, J.; Husereau, D.; Martinez-Lopez, I.; Normanno, N.; et al. Delivering Precision Oncology to Patients with Cancer. Nat. Med. 2022, 28, 658–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- NHS England. NHS Genomic Medicine Service Alliances to Help Embed Genomics into Patient Care Pathways. Available online: https://www.england.nhs.uk/blog/nhs-genomic-medicine-service-alliances-to-help-embed-genomics-into-patient-care-pathways/ (accessed on 23 June 2022).

- Kim, H.; Sefcik, J.S.; Bradway, C. Characteristics of Qualitative Descriptive Studies: A Systematic Review. Res. Nurs. Health 2017, 40, 23–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neergaard, M.A.; Olesen, F.; Andersen, R.S.; Sondergaard, J. Qualitative Description–the Poor Cousin of Health Research? BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2009, 9, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laboratories, A.P. Home. Available online: https://www.albertaprecisionlabs.ca/ (accessed on 6 April 2023).

- Laboratories, A.P. Lab Formulary Intake Request. Available online: https://www.albertaprecisionlabs.ca/tc/Page13931.aspx (accessed on 6 April 2023).

- Welcome|Alberta Diagnostic Ecosystem Platform for Translation. Available online: https://www.albertalabdiagnostics.ca (accessed on 6 April 2023).

- Submit a Suggestion for a Health Technology Assessment Topic-Health Quality Ontario (HQO). Available online: https://hqontario.ca/Evidence-to-Improve-Care/Health-Technology-Assessment/Submit-a-Suggestion-for-a-Health-Technology-Assessment-Topic (accessed on 6 April 2023).

- Home. Available online: https://pebc.healthsci.mcmaster.ca/ (accessed on 6 April 2023).

- Advisory Council|CHEO NSO. Available online: https://www.newbornscreening.on.ca/en/advisory-council (accessed on 6 April 2023).

- Jorge GSO Home. Available online: https://gsontario.ca/ (accessed on 6 April 2023).

- À Propos-Biovigilance-Professionnels de La Santé-MSSS. Available online: https://www.msss.gouv.qc.ca/professionnels/soins-et-services/biovigilance/ (accessed on 6 April 2023).

- INESSS. Available online: http://www.inesss.qc.ca/ (accessed on 6 April 2023).

- Greenhalgh, T.; Robert, G.; Macfarlane, F.; Bate, P.; Kyriakidou, O. Diffusion of Innovations in Service Organizations: Systematic Review and Recommendations. Milbank Q. 2004, 82, 581–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robert, G.; Greenhalgh, T.; Macfarlane, F.; Peacock, R. Adopting and Assimilating New Non-Pharmaceutical Technologies into Health Care: A Systematic Review. J. Health Serv. Res. Policy 2010, 15, 243–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Office of the Auditor General of Ontario Laboratory Services in the Health Sector 2017. Available online: https://www.auditor.on.ca/en/content/news/17_summaries/2017AR%20summary%203.07.pdf (accessed on 4 May 2023).

- Barwell, J.; Snape, K.; Wedderburn, S. The New Genomic Medicine Service and Implications for Patients. Clin. Med. 2019, 19, 273–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, O.M.; Bates, J.; Chanfreau-Coffinier, C.; Naglich, M.; Kelley, M.J.; Meyer, L.J.; Icardi, M.; Vassy, J.L.; Sriram, P.; Heise, C.W.; et al. Veterans Affairs Pharmacogenomic Testing for Veterans (PHASER) Clinical Program. Pharmacogenomics 2021, 22, 137–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garfield, S.; Polisena, J.; Spinner, D.S.; Postulka, A.; Lu, C.Y.; Tiwana, S.K.; Faulkner, E.; Poulios, N.; Zah, V.; Longacre, M. Health Technology Assessment for Molecular Diagnostics: Practices, Challenges, and Recommendations from the Medical Devices and Diagnostics Special Interest Group. Value Health 2016, 19, 577–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Drummond, M.F.; Schwartz, J.S.; Jönsson, B.; Luce, B.R.; Neumann, P.J.; Siebert, U.; Sullivan, S.D. Key Principles for the Improved Conduct of Health Technology Assessments for Resource Allocation Decisions. Int. J. Technol. Assess. Health Care 2008, 24, 244–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kristensen, F.B.; Husereau, D.; Huić, M.; Drummond, M.; Berger, M.L.; Bond, K.; Augustovski, F.; Booth, A.; Bridges, J.F.P.; Grimshaw, J.; et al. Identifying the Need for Good Practices in Health Technology Assessment: Summary of the ISPOR HTA Council Working Group Report on Good Practices in HTA. Value Health 2019, 22, 13–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oortwijn, W.; Husereau, D.; Abelson, J.; Barasa, E.; Bayani, D.D.; Canuto Santos, V.; Culyer, A.; Facey, K.; Grainger, D.; Kieslich, K.; et al. Designing and Implementing Deliberative Processes for Health Technology Assessment: A Good Practices Report of a Joint HTAi/ISPOR Task Force. Value Health 2022, 25, 869–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Faghfoury, H.; Guerin, A. Ensuring Timely Genetic Diagnosis in Adults. CMAJ 2023, 195, E413–E414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rubin, H.J.; Rubin, I.S. Qualitative Interviewing: The Art of Hearing Data, 2nd ed.; Sage Publications, Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

| Health System Challenge | Condition(s) Required | Good Practice Description |

|---|---|---|

| Care interruptions, wait times, and unsustainable care | (1) Resource planning | Frequent and systematic resource planning |

| (2) Finance model | Nimble, value-based funding formula (i.e., payment that accounts for development and human resource costs and benefits) | |

| Inequitable care delivery | (3) Creating communities of practice and healthcare system networks | Engagement with all stakeholders, including administrators, information and communications technology professionals, implementation and genome scientists, and public and private sector innovators |

| Uncoordinated or duplicative care | (4) Informatics | Integrated laboratory information systems and electronic health records |

| (5) Tools for awareness and care navigation | Available, up-to-date information and navigation support | |

| (6) Tools for education and training | Educational standards that address continuing professional development, knowledge updates, and transfer and quality improvement | |

| Technology creep or failure to keep up with pace of innovation | (7) Single entry/exit point for innovation proposals | Application process open to all stakeholders with explicit timelines |

| (8) Integration of innovation and healthcare delivery | Integration of future testing; private/public sector partnerships | |

| Inequitable or inefficient care | (9) Evaluative function | Consistent and adherent to key HTA principles such as timeliness and transparency |

| (10) Service model | System-wide care coordination | |

| Legal liability, low care quality | (11) Regulation | System-wide analytic standards and regulation that addresses human resource qualifications and training, documentation of records, quality control processes, and proficiency testing |

| (12) Data privacy and security | System-wide privacy standards |

| Province | Population (M)/Area (1000 km2) | Testing Centres * | Strengths | Weaknesses | Rank ** |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alberta | 4.3/661.8 | 5 |

|

| 1 |

| Quebec | 8.5/1542.0 | 7 |

|

| 2 |

| British Columbia | 5.0/944.7 | 4 |

|

| 3 |

| Nova Scotia | 0.97/55 | 2 |

|

| |

| Ontario | 14.2/1076.4 | 19 |

|

| 4 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Husereau, D.; Villalba, E.; Muthu, V.; Mengel, M.; Ivany, C.; Steuten, L.; Spinner, D.S.; Sheffield, B.; Yip, S.; Jacobs, P.; et al. Progress toward Health System Readiness for Genome-Based Testing in Canada. Curr. Oncol. 2023, 30, 5379-5394. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol30060408

Husereau D, Villalba E, Muthu V, Mengel M, Ivany C, Steuten L, Spinner DS, Sheffield B, Yip S, Jacobs P, et al. Progress toward Health System Readiness for Genome-Based Testing in Canada. Current Oncology. 2023; 30(6):5379-5394. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol30060408

Chicago/Turabian StyleHusereau, Don, Eva Villalba, Vivek Muthu, Michael Mengel, Craig Ivany, Lotte Steuten, Daryl S. Spinner, Brandon Sheffield, Stephen Yip, Philip Jacobs, and et al. 2023. "Progress toward Health System Readiness for Genome-Based Testing in Canada" Current Oncology 30, no. 6: 5379-5394. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol30060408

APA StyleHusereau, D., Villalba, E., Muthu, V., Mengel, M., Ivany, C., Steuten, L., Spinner, D. S., Sheffield, B., Yip, S., Jacobs, P., Sullivan, T., & Arshoff, L. (2023). Progress toward Health System Readiness for Genome-Based Testing in Canada. Current Oncology, 30(6), 5379-5394. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol30060408