Competency-Based Workforce Development and Education in Global Oncology

Abstract

1. Introduction

Current Status of Competency-Based Medical Education

- Competencies—These are the essential attitudes, skills and knowledge required to carry out specific tasks in sequential grades of expertise [13]. However, medical practice requires the physician to independently integrate competencies from several competency domains in multiple combinations to suit the needs of individual patients [18]

- Entrustable professional activities (EPAs)—These are globally accepted specific professional tasks the public expects all physicians to be able to carry out independently upon graduating and consist of real-life physician tasks and which have measurable outcomes [14]. EPAs are increasingly being defined for training in individual health professional specialties [15] and have recently been defined for newly graduated physicians [19]

- Essential Professional Duties—These are groups of EPAs directed at carrying out a particular recognized professional duty effectively in a specified location [20,21], i.e., locally relevant professional activities of international standard that represent identifiable outcomes against which the effectiveness of professionals in a specific community can be measured to ensure social responsiveness and accountability.

- (1)

- Clearly articulated outcome competencies required for practice

- (2)

- Sequenced progression of competencies and their developmental markers

- (3)

- Tailored learning experiences that facilitate the acquisition of competencies

- (4)

- Competency-focused instruction that promotes the acquisition of competencies

- (5)

- Programmatic assessment

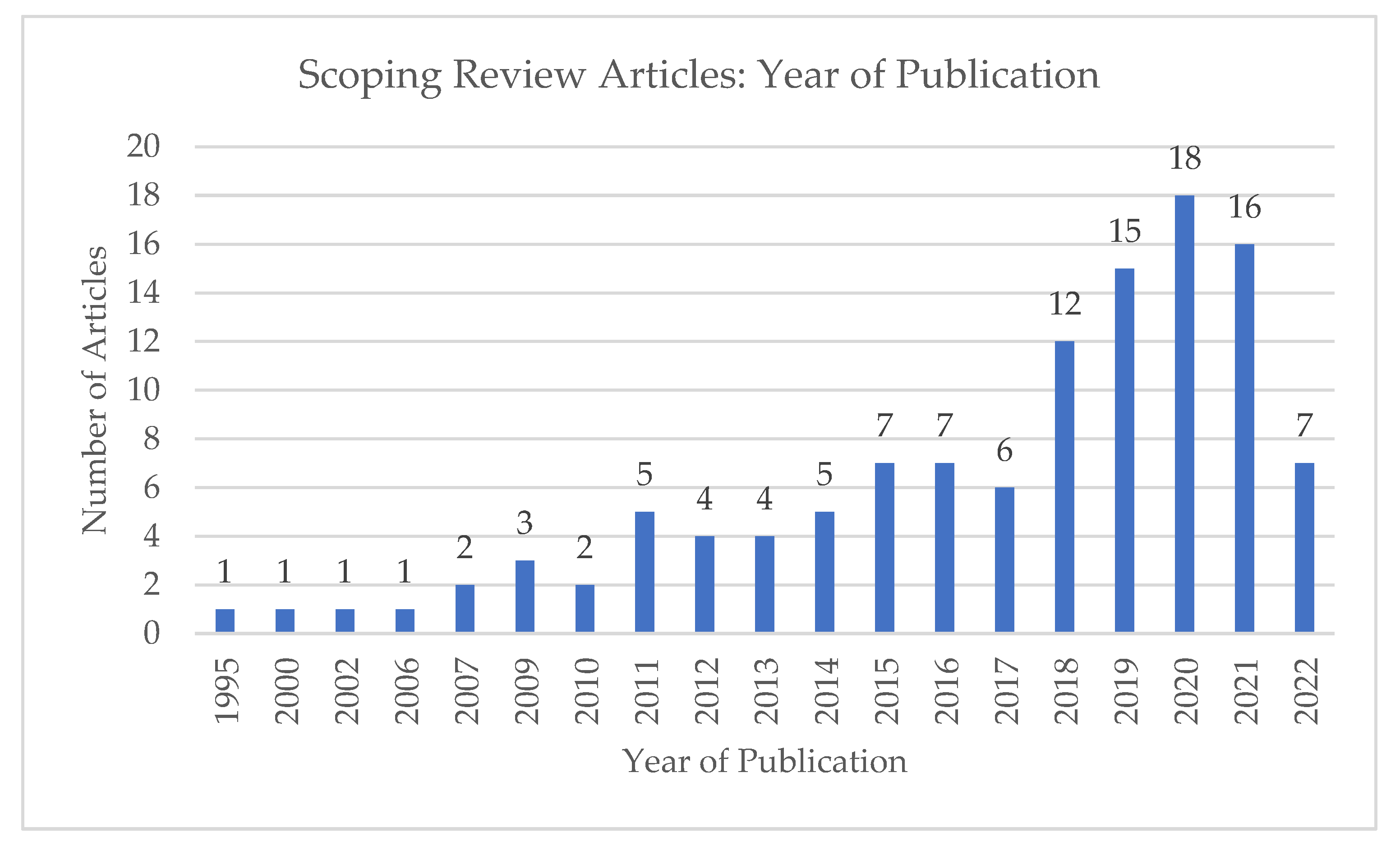

2. Scoping Review: Competency-Based Medical Education (CBME) in Oncology

3. Implementation and Evaluation

3.1. Importance of Faculty and Learner Development

3.2. Logistical and Other Obstacles

3.3. Importance of Program Structure

3.4. Opportunities for Change

3.5. Competencies in Global Oncology

4. Critical Competencies Addressing Challenges of Cancer Care in Both HIC and LMIC

4.1. Value-Based Care

4.2. Integrative Oncology

4.3. Technology-Enhanced Education

4.4. Leadership

4.5. Health Equity

5. Relevance for LMICs

6. Opportunities for Collaboration and Way Forward

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Framework for Developing a CBME Curriculum

Appendix B. Scoping Review Strategy

Appendix C. Scoping Review PRISMA Diagram

Appendix D. Table of Selected Available CBME Curricula in Medical Oncology and Clinical Oncology

| Associations | Target Audience | Competency Framework | Integrated into Curriculum? | Implementation and Assessment |

| Joint Royal College of Physicians Training Board [62] | Medical Oncology the UK 2017 | General Medical Council (GMC) Good Medical Practice (GMP) and Medical Leadership Competency Framework | Yes | UK |

| Clinical Oncology [63] | Royal College of Radiologists | Generic Professional capabilities. Rather than competencies: Capabilities in practice (CiP) GPC | Yes | UK |

| Medical Oncology Ireland: Royal College of Physicians of Ireland (RCPI): Irish Committee on Higher Medical Training version 2018 [64] | Medical oncology | Good Medical Practice (GMP) | Yes | Ireland |

| ASCO/ACGME medical oncology training [65] | Medical oncology 2021 | ACGME competencies | Yes | USA and programs in other countries accredited by ACGME International |

| The Royal Australian College of Physicians Australia [66] | Medical Oncology 2013 | The Professional Qualities Curriculum (PQC) In addition to Specific medical oncology domains and expected outcomes | Yes | Australia |

References

- World Health Organization. Transforming and Scaling up Health Professionals’ Education and Training: World Health Organization Guidelines 2013; World Health Organization: Geneva, The Switzerland, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Aggarwal, A.; Lievens, Y.; Sullivan, R.; Nolte, E. What Really Matters for Cancer Care-Health Systems Strengthening or Technological Innovation? Clin. Oncol. 2022, 34, 430–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kwizera, E.; Iputo, J. Addressing social responsibility in medical education: The African way. Med. Teach. 2011, 33, 649–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boelen, C. Building a socially accountable health professions school: Towards unity for health. Educ. Health 2004, 17, 223–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kiguli-Malwadde, E.; Omaswa, F.; Olapade-Olaopa, E.O.; Kiguli, S.; Chen, C.; Sewankambo, N.K.; Ogunniyi, A.O.; Mukwaya, S. Competency-based medical education in two Sub-Saharan African medical schools. Adv. Med. Educ. Pract. 2014, 5, 483–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmboe, E.S.; Sherbino, J.; Englander, R.; Snell, L.; Frank, J.R.; Collaborators, O.B.O.T.I. A call to action: The controversy of and rationale for competency-based medical education. Med. Teach. 2017, 39, 574–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC). Available online: https://www.aamc.org/what-we-do/mission-areas/medical-education/cbme (accessed on 6 May 2022).

- Frank, J.R.; Mungroo, R.; Ahmad, Y.; Wang, M.; De Rossi, S.; Horsley, T. Toward a definition of competency-based education in medicine: A systematic review of published definitions. Med. Teach. 2010, 32, 631–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGaghie, W.C.; Sajid, A.W.; Miller, G.E.; Telder, T.V.; Lipson, L.; World Health Organization. Competency-Based Curriculum Development in Medical Education: An Introduction; with the assistance of Laurette Lipson; World Health Organization: Geneva, The Switzerland, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Englander, R.; Flynn, T.; Call, S.; Carraccio, C.; Cleary, L.; Fulton, T.B.; Garrity, M.J.; Lieberman, S.A.; Lindeman, B.; Lypson, M.L.; et al. Toward Defining the Foundation of the MD Degree: Core Entrustable Professional Activities for Entering Residency. Acad. Med. 2016, 91, 1352–1358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrison, K.; MacNeily, A. Core competencies in surgery: Evaluating the goals of urology residency training in Canada. Can. J. Surg. 2006, 49, 259–266. [Google Scholar]

- van Houwelingen, C.T.; Moerman, A.H.; Ettema, R.G.; Kort, H.S.; Ten Cate, O. Competencies required for nursing telehealth activities: A Delphi-study. Nurse Educ. Today 2016, 39, 50–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frenk, J.; Chen, L.C.; Chandran, L.; Groff, E.O.H.; King, R.; Meleis, A.; Fineberg, H.V. Challenges and opportunities for educating health professionals after the COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet 2022, 400, 1539–1556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, M.L.; Aagaard, E.M.; Caverzagie, K.J.; Chick, D.A.; Holmboe, E.; Kane, G.; Smith, C.D.; Iobst, W. Charting the road to competence: Developmental milestones for internal medicine residency training. J. Grad. Med. Educ. 2009, 1, 5–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kogan, J.R.; Holmboe, E.; Hauer, K. Tools for direct observation and assessment of clinical skills of medical trainees: A systematic review. JAMA 2009, 302, 1316–1326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hauer, K.E.; Kohlwes, J.; Cornett, P.; Hollander, H.; Cate, O.T.; Ranji, S.R.; Soni, K.; Iobst, W.; O’Sullivan, P. Identifying entrustable professional activities in internal medicine training. J. Grad. Med. Educ. 2013, 5, 54–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olapade-Olaopa, E.O.; Fasola, A.O.; Agunloye, A.M.; Ogunbiyi, A.O.; Odukogbe, A.A.; Ogunniyi, A.O. Revising a 60-Year Old Medical and Dental Curriculum in a Medical School in Sub-Saharan Africa [Manuscript accepted for publication January 25, 2022]. Afr. J. Med. Med. Sci. 2022. Available online: https://ojshostng.com/index.php/ajmms/issue/view/107 (accessed on 4 August 2022).

- ten Cate, O.; Snell, L.; Carraccio, C. Medical competence: The interplay between individual ability and the health care environment. Med. Teach. 2010, 32, 669–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sule, H.; Lamba, S.; Wilson, B.; Natal, B.; Anana, M.; Nagurka, R. A suggested emergency medicine boot camp curriculum for medical students based on the mapping of Core Entrustable Professional Activities to Emergency Medicine Level 1 milestones. Adv. Med. Educ. Pract. 2016, 7, 115–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujihara, H.; Koinuma, M.; Yumoto, T.; Maeda, T.; Kamite, M.; Kawahara, E.; Soeda, S.; Takimoto, A.; Tamura, K.; Nakamura, M.; et al. Expected Duties of Pharmacists and Potential Needs of Physicians and Nurses on a Kaifukuki Rehabilitation Ward. YAKUGAKU ZASSHI 2015, 135, 969–975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olapade-Olaopa, E.O.; Sewankambo, N.; Iputo, J.E.; Rugarabamu, P.; Amlak, A.H.; Mipando, M. Essential professional duties for the sub-Saharan medical/dental graduate: An Association of Medical Schools of Africa initiative. Afr. J. Med. Med. Sci. 2016, 45, 221–227. [Google Scholar]

- Van Melle, E.; Frank, J.R.; Holmboe, E.S.; Dagnone, D.; Stockley, D.; Sherbino, J. A Core Components Framework for Evaluating Implementation of Competency-Based Medical Education Programs. Acad. Med. 2019, 94, 1002–1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons. CanMEDS Framework. 2022. Available online: https://www.royalcollege.ca/rcsite/canmeds/canmeds-framework-e (accessed on 1 July 2022).

- Arora, R.; Kazemi, G.; Hsu, T.; Levine, O.; Basi, S.K.; Henning, J.W.; Sussman, J.; Mukherjee, S.D. Implementing changes to a residency program curriculum before competency-based medical education: A survey of Canadian medical oncology program directors. Curr. Oncol. 2020, 27, e614–e620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomiak, A.; Braund, H.; Egan, R.; Dalgarno, N.; Emack, J.; Reid, M.-A.; Hammad, N. Exploring How the New Entrustable Professional Activity Assessment Tools Affect the Quality of Feedback Given to Medical Oncology Residents. J. Cancer Educ. 2020, 35, 165–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomiak, A.; Linford, G.; McDonald, M.; Willms, J.; Hammad, N. Implementation of Competency-Based Medical Education in a Canadian Medical Oncology Training Program: A First Year Retrospective Review. J. Cancer Educ. 2020, 37, 852–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moideen, N.; de Metz, C.; Kalyvas, M.; Soleas, E.; Egan, R.; Dalgarno, N. Aligning Requirements of Training and Assessment in Radiation Treatment Planning in the Era of Competency-Based Medical Education. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 2020, 106, 32–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Safavi, A.H.; Sienna, J.; Strang, B.K.; Hann, C. Competency-Based Medical Education in Canadian Radiation Oncology Residency Training: An Institutional Implementation Pilot Study. J. Cancer Educ. 2023, 38, 274–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turner, S.; Seel, M.; Berry, M. Radiation Oncology Training Program Curriculum developments in Australia and New Zealand: Design, implementation and evaluation—What next? J. Med. Imaging Radiat. Oncol. 2015, 59, 728–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ndlovu, N.; Ndarukwa, S.; Nyamhunga, A.; Musiwa-Mba, P.; Nyakabau, A.M.; Kadzatsa, W.; Mushonga, M. Education and training of clinical oncologists-experience from a low-resource setting in Zimbabwe. Ecancermedicalscience 2021, 15, 1208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chinula, L.; Hicks, M.; Chiudzu, G.; Tang, J.H.; Gopal, S.; Tomoka, T.; Kachingwe, J.; Pinder, L.; Hicks, M.; Sahasrabuddhe, V.; et al. A tailored approach to building specialized surgical oncology capacity: Early experiences and outcomes in Malawi. Gynecol. Oncol. Rep. 2018, 26, 60–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petz, W.; Spinoglio, G.; Choi, G.S.; Parvaiz, A.; Santiago, C.; Marecik, S.; Giulianotti, P.C.; Bianchi, P.P. Structured training and competence assessment in colorectal robotic surgery. Results of a consensus experts round table. Int. J. Med. Robot. 2016, 12, 634–641. [Google Scholar]

- Rodin, D.; Yap, M.L.; Grover, S.; Longo, J.M.; Balogun, O.; Turner, S.; Eriksen, J.G.; Coleman, C.N.; Giuliani, M. Global Health in Radiation Oncology: The Emergence of a New Career Pathway. Semin. Radiat. Oncol. 2017, 27, 118–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, T.; De Angelis, F.; Al-Asaaed, S.; Basi, S.K.; Tomiak, A.; Grenier, D.; Hammad, N.; Henning, J.-W.; Berry, S.; Song, X.; et al. Ten ways to get a grip on designing and implementing a competency-based medical education training program. Can. Med. Educ. J. 2021, 12, e81–e87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turner, S.; Seel, M.; Trotter, T.; Giuliani, M.; Benstead, K.; Eriksen, J.G.; Poortmans, P.; Verfaillie, C.; Westerveld, H.; Cross, S.; et al. Defining a Leader Role curriculum for radiation oncology: A global Delphi consensus study. Radiother. Oncol. 2017, 123, 331–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoffman, J.M. Overcoming the barriers to implementation of competence-based medical education in post-graduate medical education: A narrative literature review. Med. Educ. Online 2022, 27, 2112012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dittrich, C.; Kosty, M.; Jezdic, S.; Pyle, D.; Berardi, R.; Bergh, J.; El-Saghir, N.; Lotz, J.-P.; Österlund, P.; Pavlidis, N.; et al. ESMO/ASCO Recommendations for a Global Curriculum in Medical Oncology Edition 2016. ESMO Open 2016, 1, e000097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. WHO Report on Cancer; W.H.O.: Geneva, The Switzerland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Schnipper, L.E.; Davidson, N.E.; Wollins, D.S.; Blayney, D.W.; Dicker, A.P.; Ganz, P.A.; Hoverman, J.R.; Langdon, R.; Lyman, G.H.; Meropol, N.J.; et al. Updating the American Society of Clinical Oncology Value Framework: Revisions and Reflections in Response to Comments Received. J. Clin. Oncol. 2016, 34, 2925–2934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cherny, N.I.; Dafni, U.; Bogaerts, J.; Latino, N.J.; Pentheroudakis, G.; Douillard, J.-Y.; Tabernero, J.; Zielinski, C.; Piccart, M.J.; de Vries, E.G.E. ESMO-Magnitude of Clinical Benefit Scale version 1. 1. Ann. Oncol. 2017, 28, 2340–2366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pramesh, C.S.; Chaturvedi, H.; Reddy, V.A.; Saikia, T.; Ghoshal, S.; Pandit, M.; Babu, K.G.; Ganpathy, K.V.; Savant, D.; Mitera, G.; et al. “Choosing Wisely” for Cancer Care in India. Indian J. Surg. Oncol. 2020, 11, 4–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rubagumya, F.; Mitera, G.; Ka, S.; Manirakiza, A.; Decuir, P.; Msadabwe, S.C.; Ifè, S.A.; Nwachukwu, E.; Oti, N.O.; Borges, H.; et al. Choosing Wisely Africa: Ten Low-Value or Harmful Practices That Should Be Avoided in Cancer Care. JCO Glob. Oncol. 2020, 6, 1192–1199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Moraes, F.Y.; Marta, G.N.; Mitera, G.; Forte, D.N.; Pinheiro, R.N.; Vieira, N.F.; Gadia, R.; Caleffi, M.; Kauer, P.C.; de Camargo Barros, L.H.; et al. Choosing Wisely for oncology in Brazil: 10 recommendations to deliver evidence-based cancer care. Nat. Med. 2022, 28, 1738–1739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ting, F.I.; Uy, C.D.; Bebero, K.G.; Sacdalan, D.B.; Abarquez, H.S.; Nilo, G.; Ramos, B., Jr.; Sacdalan, D.L.; Uson, A.J. Choosing Wisely Philippines: Ten low-value or harmful practices that should be avoided in cancer care. Ecancermedicalscience 2022, 16, 1424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karim, S.; Benn, R.; Carlson, L.; Fouladbakhsh, J.; Greenlee, H.; Harris, R.; Henry, N.; Jolly, S.; Mayhew, S.; Spratke, L.; et al. Integrative Oncology Education: An Emerging Competency for Oncology Providers. Curr. Oncol. 2021, 28, 853–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roumeliotis, M.; Morrison, H.; Conroy, L.; Becker, N.; Logie, N.; Grendarova, P.; Thind, K.; McNiven, A.; Hilts, M.; Quirk, S. Competency-Based Medical Education in Radiation Therapy Treatment Planning. Pract. Radiat. Oncol. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Fernandez, C.; Croke, J.; Alfieri, J.; Golden, D.W. A guide to curriculum inquiry for brachytherapy simulation-based medical education. Brachytherapy 2020, 19, 749–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naghi, M.; Salem, M.R. A Modified Delphi Study for the Development of a Leadership Curriculum for Pediatric Oncology. Asian Pac. J. Cancer Prev. 2021, 22, 1659–1665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, E.Y.; Chuang, J.; Frakes, J.M.; Dilling, T.; Quinn, J.F.; Rosenberg, S.; Johnstone, P.; Harrison, L.; Hoffe, S.E. Developing a Dedicated Leadership Curriculum for Radiation Oncology Residents. J. Cancer Educ. 2021, 37, 1446–1453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aggarwal, R.; Swanwick, T. Clinical leadership development in postgraduate medical education and training: Policy, strategy, and delivery in the UK National Health Service. J. Healthc. Leadersh. 2015, 7, 109–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turner, S.; Chan, M.-K.; McKimm, J.; Dickson, G.; Shaw, T. Discipline-specific competency-based curricula for leadership learning in medical specialty training. Leadersh. Health Serv. 2018, 31, 152–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenblatt, E.; Ben Prajogi, G.; Barton, M.; Fidarova, E.; Eriksen, J.G.; Haffty, B.; Millar, B.A.; Bustam, A.; Zubizarreta, E.; Abdel-Wahab, M. Need for Competency-Based Radiation Oncology Education in Developing Countries. Creat. Educ. 2017, 8, 66–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jalan, D.; Rubagumya, F.; Hopman, W.M.; Vanderpuye, V.; Lopes, G.; Seruga, B.; Booth, C.M.; Berry, S.; Hammad, N. Training of oncologists: Results of a global survey. Ecancermedicalscience 2020, 14, 1074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Best, L.R.; Sengupta, A.; Murphy, R.J.; de Metz, C.; Trotter, T.; Loewen, S.K.; Ingledew, P.-A.; Sargeant, J. Transition to practice in radiation oncology: Mind the gap. Radiother. Oncol. 2019, 138, 126–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khader, J.; Al-Mousa, A.; Al Khatib, S.; Wadi-Ramahi, S. Successful Development of a Competency-Based Residency Training Program in Radiation Oncology: Our 15-Year Experience from within a Developing Country. J. Cancer Educ. Off. J. Am. Assoc. Cancer Educ. 2020, 35, 1011–1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International, A. Where We Are. Available online: https://www.acgme-i.org/about-us/where-we-are/ (accessed on 10 August 2022).

- ICBME. ICBME Collaborators—Roster. 2018 [Cited 2022 August 10]. Available online: https://gocbme.org/icbme-site/roster.html (accessed on 4 August 2022).

- World Health Organization Regional Office for Africa. Core Competencies for the Eye Health Workforce in the WHO African Region; World Health Organization, Regional Office for Africa: Brazzaville, Republic of the Congo, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Republic of Kenya Ministry of Health. Report of the Taskforce on Training of Medical Specialists; Republic of Kenya Ministry of Health: Nairobi, Kenya, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Rashid, M.A. Hyperglobalist, sceptical, and transformationalist perspectives on globalization in medical education. Med. Teach. 2022, 44, 1023–1031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Global Strategy on Human Resources for Health: Workforce 2030; World Health Organization: Geneva, The Switzerland, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Pramesh, C.S.; Badwe, R.A.; Bhoo-Pathy, N.; Booth, C.M.; Chinnaswamy, G.; Dare, A.J.; de Andrade, V.P.; Hunter, D.J.; Gopal, S.; Gospodarowicz, M.; et al. Priorities for cancer research in low- and middle-income countries: A global perspective. Nat. Med. 2022, 28, 649–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joint Royal Colleges of Physicians Training Board. Specialty Training Curriculum for Medical Oncology; Joint Royal Colleges of Physicians Training Board: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Royal College of Radiologists, Clinical Oncology Specialty Training Curriculum. 2021. [Cited 2022 August 10]. Available online: https://www.rcr.ac.uk/sites/default/files/clinical_oncology_curriculum_2021.pdf (accessed on 4 August 2022).

- Royal College of Physicians of Ireland Institute of Medicine, Higher Specialist Training in Medical Oncology, Farrington, K. Editor. Royal College of Physicians of Ireland, Ireland. 2022. [Cited 2022 August 10]. Available online: https://rcpi-live-cdn.s3.amazonaws.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/HST-Medical-Oncology-Curriculum-2022.pdf (accessed on 4 August 2022).

- The Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education, Hematology and Medical Oncology Milestones. 2019. The Royal Australasian College of Physicians, Physician Readiness for Expert Practice (PREP) Training Program: Medical Oncology Advanced Training Curriculum, The Royal Australian College of Physicians (RACP), Editor. First edition 2010 (Revised 2013). [Cited 2022 August 10]. Available online: https://www.racp.edu.au/docs/default-source/trainees/advanced-training/medical-oncology/medical-oncology-adult-medicine-advanced-training-curriculum.pdf?sfvrsn=75222c1a_8 (accessed on 4 August 2022).

| Category | Number of Included Articles (%) |

|---|---|

| Competency Outlines | 64 (54.7) |

| Program Evaluation | 28 (23.9) |

| Needs Assessment | 25 (21.4) |

| Professional Category *Note: Oncology nursing was counted as “nursing” | Number of Included Articles (%) |

| Oncology-Related Medical Disciplines | 63 (53.8) |

| Clinical Oncology | 3 (2.6) |

| General Oncology | 12 (10.3) |

| Global Oncology | 1 (0.9) |

| Gynecologic Oncology | 2 (1.7) |

| Medical Oncology | 4 (3.4) |

| Neuro-Oncology | 1 (0.9) |

| Pediatric Oncology | 4 (3.4) |

| Psychosocial Oncology | 1 (0.9) |

| Radiation Oncology | 27 (23.1) |

| Surgical Oncology | 5 (4.3) |

| Hematology | 3 (2.6) |

| Nursing | 37 (31.6) |

| Medical Physics | 6 (5.1) |

| General Medicine | 4 (3.4) |

| Community/Public Health | 2 (1.7) |

| Palliative Care | 2 (1.7) |

| Research | 2 (1.7) |

| Genomics | 1 (0.9) |

| Massage Therapy | 1 (0.9) |

| Multiple | 1 (0.9) |

| Patient Educators | 1 (0.9) |

| Pharmacy | 1 (0.9) |

| Specialty | Author(s) | Country | Study Type | Size | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Medical Oncology | Arora 2020 et al. [24] | Canada | National Pre-CBME Implementation Survey | 14/15 Program Directors |

Describes major structural and curricular changes while transitioning to CBME including

|

| Tomiak 2020 et al. [25] | Canada | Single Institution Mixed Methods Pre CBME Implementation Pilot | 17 workplace-based assessments Resident Focus Group (n = 4) Faculty Interviews (n = 5) | Identified 9 lessons learned during implementation in Canadian Med Onc Program (1) faculty and resident development and engagement; (2) sharing the work of CBME; (3) collaboration and communication; (4) global assessment; (5) assessment plan challenges; (6) burden of CBME; (7) limitations of e- portfolio; (8) importance of early tracking of resident progress; and (9) culture change | |

| Tomiak 2020 et al. [26] | Canada | Single Institution Retrospective Review of First Year of CBME Implementation | 157 Assessments by 9 Faculty | Six main findings: (1) Verbal feedback is preferred over written; (2) Providing both written and verbal feedback is important; (3) Effective feedback was seen as timely, specific, and actionable; (4) The process was conceptualized as coaching rather than high stakes; (5) There were logistical concerns about the WBAs, and additional clarification about the WBA tools is needed. | |

| Radiation Oncology | Moideen 2019 et al. [27] | Canada | Single Institution Qualitative Study | 11 Radiation Oncologists 7 Residents 7 Dosimetrists | 3 Themes: (1) Strengths of treatment planning in CBME: Challenges of treatment planning in CBME, Competency-based assessments enrich student learning, Increased engagement in the feedback process will act as a catalyst for more useful and frequent feedback. (2) Challenges of treatment planning in CBME Workload demands, Clear expectations for competency at each training stage, Need for systemic cultural change (3) Opportunities for change Development of a library of cases, Structured formative treatment planning assessments, Innovative teaching and learning strategies to support the development of quality treatment plans |

| Safavi 2021 et al. [28] | Canada | Single Institution Mixed Methods Implementation Pilot | 7 Radiation Oncologists 6 Residents | Three Themes: (1) Direct observation is the most challenging aspect of CBD to implement; (2) feedback content can be improved; and (3) staff attitude, clinical workflow, and inaccessibility of assessment forms are the primary barriers to completing assessments | |

| Turner 2015 et al. [29] | Australia New Zealand | National External Independent Mixed Methods Evaluation | 35/45 Training Sites 200 Faculty Interviews 119 Faculty Survey Respondents 80 Faculty Interviews 38 Faculty Survey Respondents | Over 90% responding that it ‘provided direction in attaining competencies’. Most (87/107; 81%) said it ‘promotes regular, productive interaction between trainees and supervisors’. Adequacy of feedback to trainees was rated as only ‘average’ by trainees/trainers in one-third of cases. Consultations revealed this was more common where trainers were less familiar with curriculum tools. Half of training directors/supervisors felt better supported. Nearly two-third of all responders (58/92; 63%) stated that clinical service requirements could be met during training; 17/92 (18.5%) felt otherwise. When asked about ‘work-readiness’, 59/90 (66%) respondents, including trainees, felt this was improved. | |

| Clinical Oncology | Ndlovu 2021 et al. [30] | Zimbabwe | National Description of the CO programme and its progression from knowledge-based to competency-based | Not applicable | The curriculum is being reviewed working towards standardizing it across the African context and including domains of competency skills such as: clinical decision-making, communication, knowledge, attitude required for the above appropriately. |

| Specific surgical skills training in cervical cancer treatment | Chinula 2018 et al. [31] | Malawi | National A description of a narrow, specific competency-based skills training for performing radical abdominal hysterectomy and bilateral pelvic lymphadenectomy in a relatively short period of time | Performed at Kamuzu Central Hosp, a 1000-bed teaching hospital in Lilongwe. Board certified Malawian ObGyns trained by two US-board certified gyn-oncology master trainers. | Self-directed learning; Onsite training; Intraop assessment of tech skills; Continued E-learning with master trainer. During first 24 months of programme 28 patients underwent surgery by one trainee. During the first 5-day practicum 7 cases operated on by trainee and master trainer; 8th case performed exclusively by unsupervised trainee on the last day; 20 cases operated on independently by trainee over the course of 24 months. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hammad, N.; Ndlovu, N.; Carson, L.M.; Ramogola-Masire, D.; Mallick, I.; Berry, S.; Olapade-Olaopa, E.O. Competency-Based Workforce Development and Education in Global Oncology. Curr. Oncol. 2023, 30, 1760-1775. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol30020136

Hammad N, Ndlovu N, Carson LM, Ramogola-Masire D, Mallick I, Berry S, Olapade-Olaopa EO. Competency-Based Workforce Development and Education in Global Oncology. Current Oncology. 2023; 30(2):1760-1775. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol30020136

Chicago/Turabian StyleHammad, Nazik, Ntokozo Ndlovu, Laura Mae Carson, Doreen Ramogola-Masire, Indranil Mallick, Scott Berry, and E. Oluwabunmi Olapade-Olaopa. 2023. "Competency-Based Workforce Development and Education in Global Oncology" Current Oncology 30, no. 2: 1760-1775. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol30020136

APA StyleHammad, N., Ndlovu, N., Carson, L. M., Ramogola-Masire, D., Mallick, I., Berry, S., & Olapade-Olaopa, E. O. (2023). Competency-Based Workforce Development and Education in Global Oncology. Current Oncology, 30(2), 1760-1775. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol30020136