Iron Surveillance and Management in Gastro-Intestinal Oncology Patients: A National Physician Survey †

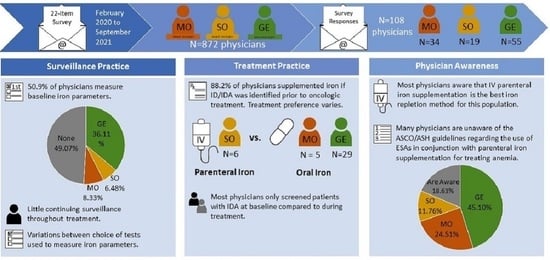

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Study Design and Population

2.2. Data Collection and Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Physician Characteristics

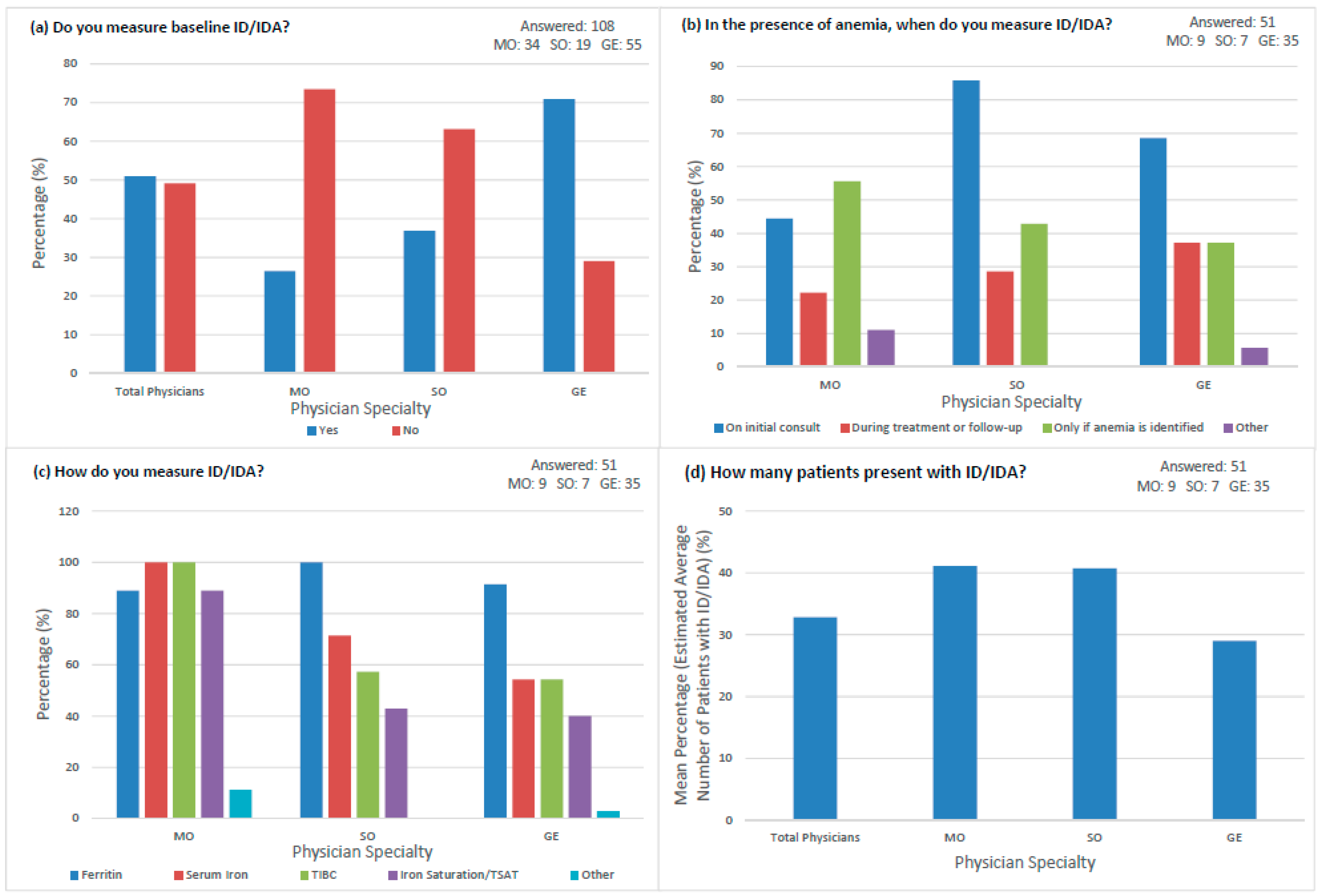

3.2. Surveillance Practices

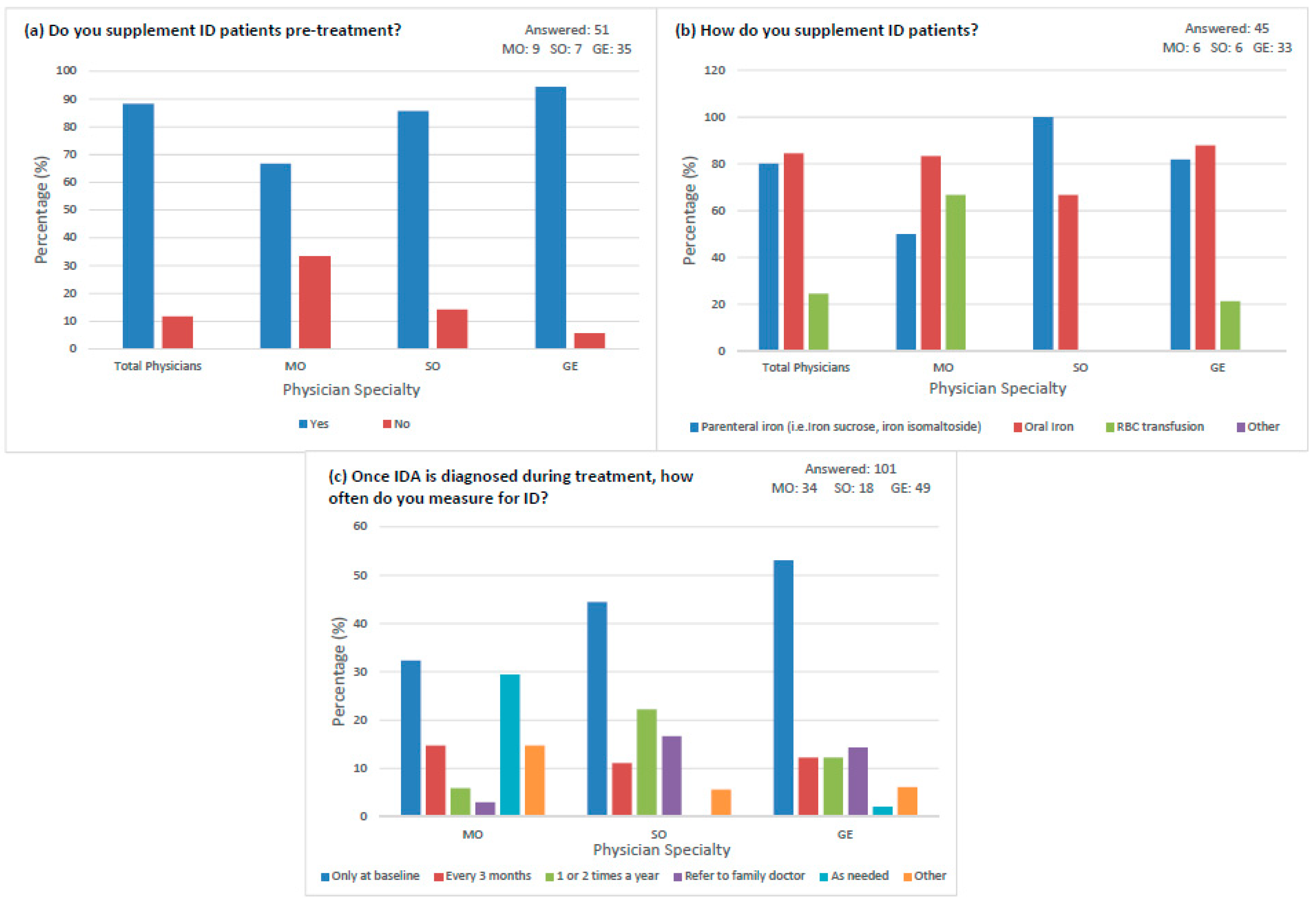

3.3. Treatment Practices

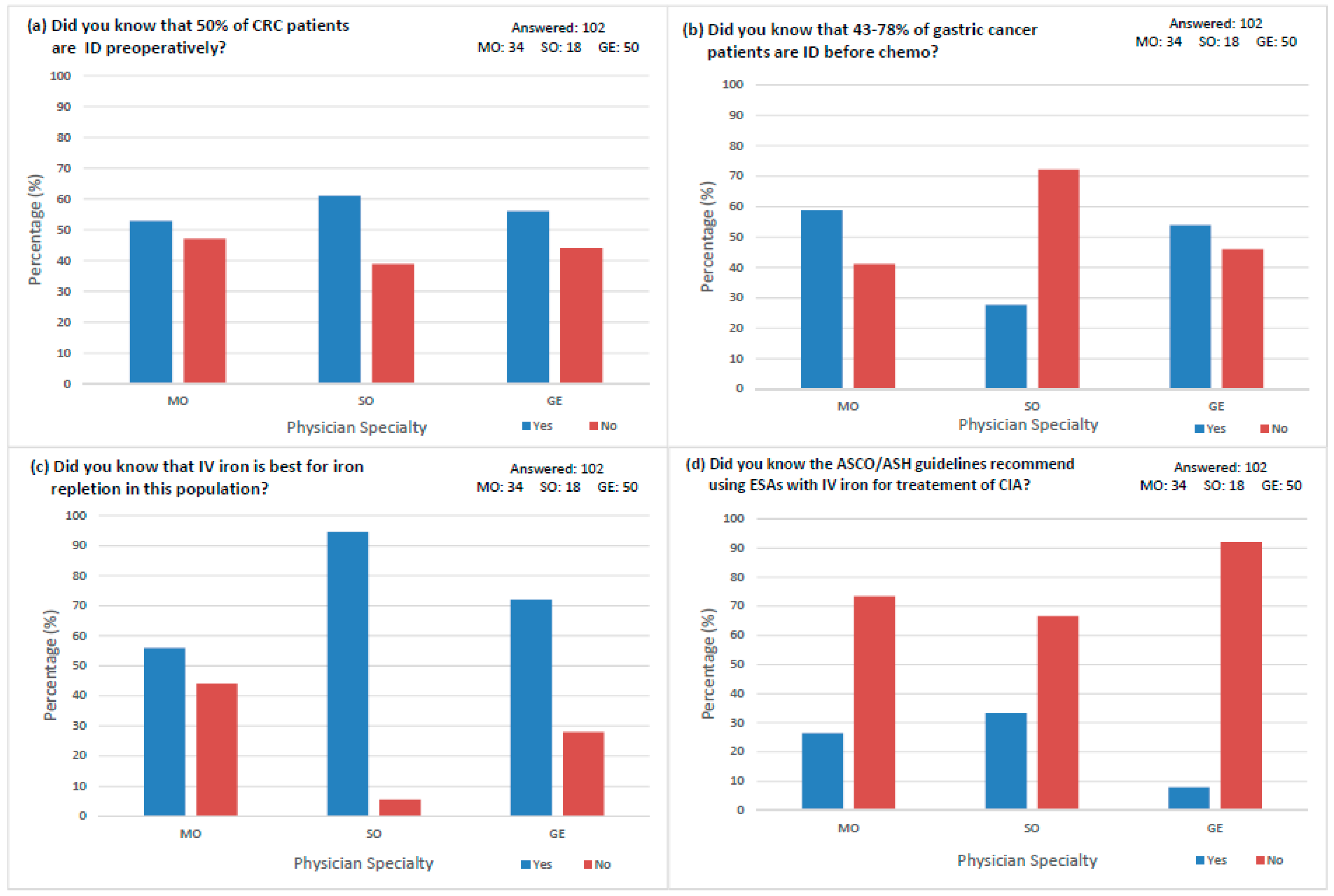

3.4. Physician Awareness

4. Discussion

4.1. Lack of Adequate Iron Surveillance

4.2. Lack of Evidence-Based IDA Treatment

4.3. Self-Selection Bias

4.4. Lack of Physician Awareness

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Term | Definition |

|---|---|

| Absolute iron deficiency (AID) | Iron deficiency that occurs when iron reserves are depleted. |

| American Society of Clinical Oncology/American Society of Hematology (ASCO/ASH) | Societies that establish guidelines with recommendations of treatment and care methods for clinicians. |

| Chemotherapy-induced anemia (CIA) | Development of acute anemia in relation to initiation of myelosuppressive chemotherapy. |

| Colorectal cancer (CRC) | Type of cancer affecting the colon and/or rectum. |

| Erythropoiesis stimulating agents (ESA) | Synthetic proteins used to increase the production of red blood cells. |

| Functional iron deficiency (FID) | Iron deficiency that occurs when there is a lack of biologically available iron due to cancer associated cytokine release. |

| Gastroenterologists (GE) | Physicians trained to diagnose and treat problems in the gastrointestinal tract and liver. |

| Gastrointestinal (GI) | The gastrointestinal tract refers to the stomach, colon, and rectum. |

| Hemoglobin (Hb) | Protein located in red blood cells responsible for carrying oxygen. |

| Intravenous (IV) | Medical technique used to inject formulated fluids directly into a vein. |

| Iron deficiency (ID) | Decrease in total iron content in the body. |

| Iron deficiency anemia (IDA) | Iron deficiency defined by a decreased total amount of hemoglobin or decreased number of red blood cells. |

| Medical oncologists (MO) | Physicians specialized in the diagnoses, treatment, and prevention of cancer. |

| Quality of Life (QoL) | An individual’s perception of their overall well-being assessed in the context of personal health in this study. |

| Red blood cells (RBC) | Cells that carry oxygen from the lungs to be delivered all over the body. |

| Red blood cell (RBC) transfusion | Procedure involving the donation of blood through an intravenous line. |

| Standard Deviation (SD) | Measure demonstrating the amount of variation from a mean. |

| Sucrosomial iron (SI) | Innovative method of oral iron supplementation in which ferric pyrophosphate is protected by a phospholipid bilayer and a sucrester matrix (sucrosome). |

| Surgical oncologists (SO) | Physicians focused on the treatment of cancer using surgical methods. |

| Total iron binding capacity (TIBC) | Blood test used to measure the ability of blood to bind to iron and transport it throughout the body. |

| Transferrin saturation (TSAT) | Ratio of serum iron to total iron binding capacity. Also referred to as iron saturation. |

References

- Lee, S. Colorectal Cancer Statistics. Canadian Cancer Society. Available online: https://cancer.ca/en/cancer-information/cancer-types/colorectal/statistics (accessed on 28 March 2023).

- Lee, S. Stomach Cancer Statistics. Canadian Cancer Society. Available online: https://cancer.ca/en/cancer-information/cancer-types/stomach/statistics (accessed on 28 March 2023).

- Ludwig, H.; Müldür, E.; Endler, G.; Hübl, W. Prevalence of iron deficiency across different tumors and its association with poor performance status, disease status and anemia. Ann Oncol. 2013, 24, 1886–1892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verraes, K.; Prenen, H. Iron deficiency in gastrointestinal oncology. Ann. Gastroenterol. 2015, 28, 19–24. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Beale, A.L.; Penney, M.D.; Allison, M.C. The prevalence of iron deficiency among patients presenting with colorectal cancer. Color. Dis. 2005, 7, 398–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ludwig, H.; Van Belle, S.; Barrett-Lee, P.; Birgegård, G.; Bokemeyer, C.; Gascón, P.; Kosmidis, P.; Krzakowski, M.; Nortier, J.; Olmi, P.; et al. The European Cancer Anaemia Survey (ECAS): A large, multinational, prospective survey defining the prevalence, incidence, and treatment of anaemia in cancer patients. Eur. J. Cancer 2004, 40, 2293–2306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Busti, F.; Marchi, G.; Ugolini, S.; Castagna, A.; Girelli, D. Anemia and Iron Deficiency in Cancer Patients: Role of Iron Replacement Therapy. Pharmaceuticals 2018, 11, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naoum, F.A. Iron deficiency in cancer patients. Rev. Bras. Hematol Hemoter. 2016, 38, 325–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ludwig, H.; Evstatiev, R.; Kornek, G.; Aapro, M.; Bauernhofer, T.; Buxhofer-Ausch, V.; Fridrik, M.; Geissler, D.; Geissler, K.; Gisslinger, H.; et al. Iron metabolism and iron supplementation in cancer patients. Wien. Klin. Wochenschr. 2015, 127, 907–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bermejo, F.; Garcia-Lopez, S. A guide to diagnosis of iron deficiency and iron deficiency anemia in digestive diseases. World J. Gastroenterol. 2009, 15, 4638–4643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groopman, J.E.; Itri, L.M. Chemotherapy-induced anemia in adults: Incidence and treatment. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 1999, 91, 1616–1634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Xu, L.; Page, J.H.; Cannavale, K.; Sattayapiwat, O.; Rodriguez, R.; Chao, C. Incidence of anemia in patients diagnosed with solid tumors receiving chemotherapy, 2010–2013. Clin. Epidemiol. 2016, 8, 61–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harper, P.; Littlewood, T. Anaemia of cancer: Impact on patient fatigue and long-term outcome. Oncology 2005, 69, 2–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caro, J.J.; Salas, M.; Ward, A.; Goss, G. Anemia as an independent prognostic factor for survival in patients with cancer: A systemic, quantitative review. Cancer 2001, 91, 2214–2221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, H.; Pallister, C.J. The impact of anaemia on outcome in cancer. Clin. Lab. Haematol. 2005, 27, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson-Wimbley, T.D.; Graham, D.Y. Diagnosis and management of iron deficiency anemia in the 21st century. Therap. Adv. Gastroenterol. 2011, 4, 177–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borstlap, W.A.A.; Buskens, C.J.; Tytgat, K.M.A.J.; Tuynman, J.B.; Consten, E.C.J.; Tolboom, R.C.; Heuff, G.; van Geloven, N.; van Wagensveld, B.A.; Wientjes, C.A.; et al. Multicentre randomized controlled trial comparing ferric (III) carboxymaltose infusion with oral iron supplementation in the treatment of preoperative anaemia in colorectal cancer patients. BMC Surg. 2015, 1, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Litton, E.; Xiao, M.H.; Ho, K.M. Safety and efficacy of intravenous iron therapy in reducing requirement for allogeneic blood transfusion: Systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised clinical trials. Bmj 2013, 347, f4822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bloor, S.R.; Schutte, R.; Hobson, A.R. Oral iron supplementation—Gastrointestinal side effects and the impact on the gut microbiota. Microbiol. Res. 2021, 12, 491–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marik, P.E.; Corwin, H.L. Efficacy of red blood cell transfusion in the critically ill: A systematic review of the literature. Crit. Care Med. 2008, 36, 2667–2674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Whitehead, L. Managing Chemotherapy-Induced Anemia with Erythropoiesis Stimulating Agents Plus Iron. Am. J. Nurs. 2017, 117, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mhaskar, R.; Wao, H.; Miladinovic, B.; Kumar, A.; Djulbegovic, B. The role of iron in the management of chemotherapy-induced anemia in cancer patients receiving erythropoiesis-stimulating agents. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2016, 2, CD009624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohlius, J.; Bohlke, K.; Castelli, R.; Djulbegovic, B.; Lustberg, M.B.; Martino, M.; Mountzios, G.; Peswani, N.; Porter, L.; Tanaka, T.N.; et al. Management of cancer-associated anemia with erythropoiesis stimulating agents: ASCO/ASH clinical practice guideline update. J. Clin. Oncol. 2019, 37, 1336–1351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, C.H.; Kim, S.W.; Kim, W.C.; Kim, J.S.; Cho, Y.K.; Park, J.M.; Lee, I.S.; Choi, M.G.; Song, K.Y.; Jeon, H.M.; et al. Anemia after gastrectomy for early gastric cancer: Long-term follow-up observational study. World J. Gastroenterol. 2012, 18, 6114–6119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ludwig, H.; Aapro, M.; Bokemeyer, C.; Glaspy, J.; Hedenus, M.; Littlewood, T.J.; Österborg, A.; Rzychon, B.; Mitchell, D.; Begiun, Y. A European patient record study on diagnosis and treatment of chemotherapy-induced anaemia. Support. Care Cancer 2014, 22, 2197–2206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muñoz, M.; Acheson, A.G.; Auerbach, M.; Besser, M.; Habler, O.; Kehlet, H.; Liumbruno, G.M.; Lasocki, S.; Meybohm, P.; Rao Baikady, R.; et al. International consensus statement on the peri-operative management of anaemia and iron deficiency. Anaesthesia 2017, 72, 233–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchrits, S.; Itzhaki, O.; Avni, T.; Raanani, P.; Gafter-Gvili, A. Intravenous iron supplementation for the treatment of chemotherapy-induced anemia: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 4156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gómez-Ramírez, S.; Brilli, E.; Tarantio, G.; Muñoz, M. Sucrosomial® Iron: A New Generation Iron for Improving Oral Supplementation. Pharmaceuticals 2018, 11, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giordano, G.; Napolitano, M.; Di Battista, V.; Lucchesi, A. Oral high-dose sucrosomial iron vs intravenous iron in sideropenic anemia patients intolerant/refractory to iron sulfate: A multicentric randomized study. Randomized Control. Trial. 2021, 100, 2173–2179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ning, S.; Zeller, M.P. Management of iron deficiency. Hematol. Am. Soc. Hematol. Educ. Program 2019, 1, 315–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choosing Wisely Canada. Transfusion Medicine. Available online: https://choosingwiselycanada.org/recommendation/transfusion-medicine/ (accessed on 28 March 2023).

- Wilson, M.J.; Dekker, J.W.T.; Harlaar, J.J.; Jeekel, J.; Schipperus, M.; Zwaginga, J.J. The role of preoperative iron deficiency in colorectal cancer patients: Prevalence and treatment. Int. J. Color. Dis. 2017, 32, 1617–1624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, G.H.; Hart, R.; Sholzberg, M.; Brezden-Masley, C. Iron deficiency anemia in gastric cancer: A Canadian retrospective review. Eur. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2018, 30, 1497–1501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cappellini, M.D.; Musallam, K.M.; Taher, A.T. Iron deficiency anaemia revisited. J. Intern. Med. 2019, 287, 153–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kam, P.M.; Chu, C.W.; Chan, E.M.; Liu, O.; Kwok, K. Use of intravenous iron therapy in colorectal cancer patient with iron deficiency anemia: A propensity-score matched study. Int. J. Color. Dis. 2020, 35, 521–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dale, W.; Williams, G.R.; MacKenzie, A.R.; Soto-Perez-de-Celis, E.; Maggiore, R.J.; Merrill, J.K.; Katta, S.; Smith, K.T.; Klepin, H.D. How Is Geriatric Assessment Used in Clinical Practice for Older Adults with Cancer? A Survey of Cancer Providers by the American Society of Clinical Oncology. JCO Oncol. Pract. 2021, 17, 336–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilson, M.J.; Koopman-van Gemert, A.W.M.M.; Harlaar, J.J.; Keekel, J.; Zwaginga, J.J.; Schipperus, M. Patient blood management in colorectal cancer patients: A survey among Dutch gastroenterologists, surgeons, and anesthesiologists. Transfusion 2018, 58, 2345–2351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tinmouth, A.; Lett, R.; Musuka, C.; Pavenski, K.; Petraszko, T.; Rad, T.; Whitman, L.; Smith, T.; Skaff, R.; Kahlon, H. NAC Position Statement on Patient Blood Management. National Advisory Committee on Blood and Blood Products. Available online: https://nacblood.ca/en/resource/nac-patient-blood-management-statement (accessed on 24 September 2023).

| Medical Oncologists n = 34 | Surgical Oncologists n = 19 | Gastroenterologists n = 55 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender, Male | 19 (55.9%) | 8 (42.1%) | 38 (69.1%) |

| Years of Practice (mean ± SD) | 13.2 ± 11.0 | 14.0 ± 10.2 | 13.4 ± 8.9 |

| 0–5 | 9 (28.1%) | 4 (21.1%) | 10 (19.2%) |

| 6–10 | 6 (18.8%) | 5 (26.3%) | 14 (26.9%) |

| 11–20 | 11 (34.4%) | 7 (36.8%) | 18 (34.6%) |

| >20 | 6 (18.8%) | 3 (15.8%) | 10 (19.2%) |

| Province of Practice | |||

| ON | 24 (70.6%) | 15 (78.9%) | 32 (59.3%) |

| QC | 3 (8.8%) | 1 (5.3%) | 3 (5.6%) |

| NS | 2 (5.9%) | 0 (0.0%) | 2 (3.7%) |

| NB | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| NL | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (5.3%) | 1 (1.9%) |

| PE | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| MB | 2 (5.9%) | 1 (5.3%) | 4 (7.4%) |

| AB | 1 (2.9%) | 0 (0.0%) | 8 (14.8%) |

| SK | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (5.3%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| BC | 2 (5.9%) | 0 (0.0%) | 4 (7.4%) |

| NU | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| YT | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| NT | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Institution Type | |||

| Academic/Teaching | 27 (79.4%) | 12 (63.2%) | 37 (68.5%) |

| Community | 7 (20.6%) | 7 (36.8%) | 16 (29.6%) |

| Private | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (1.9%) |

| Number of luminal GI tumor patients/month (mean ± SD) + | 33.9 ± 36.0 | 12.1 ± 40.3 | 16.8 ± 28.7 |

| 0–5 | 5 (14.7%) | 11 (57.9%) | 34 (61.8%) |

| 6–10 | 6 (17.6%) | 3 (15.8%) | 15 (27.3%) |

| 11–20 | 7 (20.6%) | 2 (10.5%) | 3 (5.5%) |

| 21–40 | 7 (20.6%) | 1 (5.3%) | 2 (3.6%) |

| 41–60 | 4 (11.8%) | 1 (5.3%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| 60+ | 5 (14.7%) | 1 (5.3%) | 1 (1.8%) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Richard, E.S.; Hrycyshyn, A.; Salman, N.; Remtulla Tharani, A.; Abbruzzino, A.; Smith, J.; Kachura, J.J.; Sholzberg, M.; Mosko, J.D.; Chadi, S.A.; et al. Iron Surveillance and Management in Gastro-Intestinal Oncology Patients: A National Physician Survey. Curr. Oncol. 2023, 30, 9836-9848. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol30110714

Richard ES, Hrycyshyn A, Salman N, Remtulla Tharani A, Abbruzzino A, Smith J, Kachura JJ, Sholzberg M, Mosko JD, Chadi SA, et al. Iron Surveillance and Management in Gastro-Intestinal Oncology Patients: A National Physician Survey. Current Oncology. 2023; 30(11):9836-9848. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol30110714

Chicago/Turabian StyleRichard, Emilie S., Adriyan Hrycyshyn, Noor Salman, Alliya Remtulla Tharani, Alexandria Abbruzzino, Janet Smith, Jacob J. Kachura, Michelle Sholzberg, Jeffrey D. Mosko, Sami A. Chadi, and et al. 2023. "Iron Surveillance and Management in Gastro-Intestinal Oncology Patients: A National Physician Survey" Current Oncology 30, no. 11: 9836-9848. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol30110714

APA StyleRichard, E. S., Hrycyshyn, A., Salman, N., Remtulla Tharani, A., Abbruzzino, A., Smith, J., Kachura, J. J., Sholzberg, M., Mosko, J. D., Chadi, S. A., Burkes, R. L., Pankiw, M., & Brezden-Masley, C. (2023). Iron Surveillance and Management in Gastro-Intestinal Oncology Patients: A National Physician Survey. Current Oncology, 30(11), 9836-9848. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol30110714