Abstract

(1) Background: Recurrent and/or metastatic patients with head and neck squamous cell carcinoma show a poor prognosis, which has not changed significantly in 30 years. Preserving quality of life is a primary goal for this subset of patients; (2) Methods: A group of 19 physicians working in South Italy and daily involved in head and neck cancer care took an anonymous online survey aimed at revealing the level of knowledge and the application of communication techniques in daily patient care; (3) Results: Several specialists, 18 out 19 (95%), considered that patient participation in therapeutic choices is mandatory. The main obstacles to complete and reciprocate communication still consist of lack of time and staff, but also in the need for greater organization, which goes beyond the multidisciplinary strategy already used; (4) Conclusions: A greater impulse to training and updating on issues related to counseling can improve communication between the different clinicians involved in the treatment plan.

1. Introduction

Head and neck (H&N) cancers are a complex and heterogeneous group of malignancies that require multifaceted treatment strategies and the input of several specialties. Despite the advances in multimodal treatments, the prognosis remains poor due to the high rate of advanced disease at diagnosis and the high rate of recurrence. At least 50% of patients with locally advanced disease are likely to develop locoregional or distant relapses within the first 2 years of treatment [1]. For this subset of patients, improved patient–physician communication is essential in the context of serious and life-limiting illnesses, with clear effects of good communication on quality of care and quality of life (QoL). In addition, an ethical mandate by which patients are involved and participate in informed decisions about their care is also essential [2]. In advanced H&N cancer, inadequate communication about prognosis and treatment choices is frequent [3] and is associated with unrealistic patient expectations about curability and with an aggressive treatment proposal that is not consistent with patient preferences [4,5]. Within the hospital, critical conversations typically do not occur or occur shortly before the start of the treatment program. Most advanced cancer patients want to be actively involved in their care and request open and sensitive conversations about quality of life, prognosis, and treatment choices [6]. Patient participation in treatment decision improves patient satisfaction and treatment adherence, positively influencing oncological care [7]. Multimodal treatment with a multidisciplinary team has become the standard option with a positive impact on patient assessment and management, improving the survival of stage IV patients [8,9]. However, this approach can represent a barrier to the participation of real patients, because values and preferences are not acknowledged during multidisciplinary discussion, which has been described in the health care field as ‘in absentia’ [10].

Clinicians often feel unprepared to have conversations that can include emotional reactions and address challenging side effects related to treatment. These difficulties are greater in the setting of patients who need palliative care, and are independent of the experience of the doctors [11]. In clinical practice, clinicians frequently think they are better communicators than their colleagues or their patients’ opinion [12]; however, it represents only an illusion and often communication is not happening. The discussion of controversial topics, such as treatment complications and lifestyle outcomes, should be aimed with particular attention to feelings. Patients with advanced H&N cancers prefer that clinicians discuss the topic and expect that they do [13]. Among patients with head and neck cancer, those awaiting the start of palliative chemotherapy are expected to have the highest degree of distress. Long periods of treatment, repeated hospitalization, and side effects of chemotherapy can affect the psychological status of these patients and influence communication with specialists. The major problem with communication is the illusion that it has occurred. Knowledge of strengths such as the involvement of a family member or patient autonomy and weaknesses such as caregiver disagreement or time and reimbursement constraints with health professionals can facilitate the development of patient-centered care [14]. The purpose of this observational study was to investigate the level of knowledge of counseling among clinicians involved in the treatment of H&N cancer and to highlight the barriers and aspects of the doctor–patient and doctor–family relationships that need improvement.

2. Materials and Methods

Data were collected between January 2020 and March 2020, using an anonymous online survey administered to 19 specialist physicians, through the SurveyMonkey ® platform. The group of 19 physicians, working in South Italy and selected according to their daily involvement in H&N care, included oncologists and radiotherapists. We have included in the present study professional persons with consolidated experience in the specific field of at least 10 years All of them who had participated in a course on counseling dedicated to the patient with squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck (SSCHN). The affiliations of all the participants are as follows: S. B., Radiotherapy Unit Asp di Siracusa (Sicily); B. S., Radiotherapy Unit INT Pascale Naples (Campania); A.C., Radiotherapy UNIT Centro Aktis Marano (Campania); M.C., Radiotherapy UNIT Acerra ASLNA2NORD (Campania); A. M., Di Grazia Humanitas Oncology Unit CCO Catania (Sicily); I. D., Radiotherapy UNIT Ospedale del Mare Naples (Campania); F. D., Radiotherapy Unit Cen-tro Morrone Caserta; M.F., Oncology Unit AOU Vanvitelli Naples (Campania); I F, Unit on Clinic Radiotherapy Macchiarella Palermo (Sicily); D G, Oncology Unit AO San Pio Benevento (Campania); M.G., Oncology Unit spedale Oncologico “A. Businco” Cagliari (Sardegna); F. P. and S.C., Oncologia Clinica Sperimentale Testa-Collo INT Pascale Naples (Campania); T.P., UO Radioterapia AO San Pio Benevento (Campania); N.R., Oncology Unit Policlinico Vittorio Emanuele Cata-nia (Sicily); G.R., Oncologist Ospedale Vito Fazzi di Lecce (Puglia); A.S., Oncologist Ospedale del Mare Naples (Campania); R S, Radiotherapy istituto DAM Nocera Inferiore (Campania); M. S., Oncology Unit Ospedale Giglio Cefalù (Sicily); and G. T., Oncology Unit Sant Anna e San Se-bastiano Caserta (Campania).Written informed consent was obtained from all participants. All the investigators returned the questionnaire (ratio of acceptance 100%), marking only with initials, and were therefore included in the analysis. This survey was specifically organized to investigate the value and level of knowledge of shared communication and counseling in the management of cancer patients (Table 1).

Table 1.

The questionnaire proposed to clinicians involved in the treatment of patients with metastatic head and neck cancer.

Seventeen questions, including 14 multiple choice questions, were submitted to the participants. The first part of the survey, points 1 through 6, investigated the state of the art shared with patient suffering from H&N cancers and the role of counseling. In the remaining 9 questions, we investigated the needs and critical issues that hinder and limit shared communication.

3. Results

All physicians, clinical oncologists, and radiotherapists specialized in the treatment of H&N cancer who attended a meeting on the counseling of H&N cancer patients in Naples during November 2019 returned the questionnaire (rate of acceptance 100%) and therefore were included in the analysis. Most of the respondents to the first question, 8 out of 19, (40%) considered clear and complete communication as the foundation that strengthens a therapeutic alliance, also pointing out the need to have organized and efficient healthcare personnel. To confirm these data, 12 out of 19 medical doctors (65%) considered that investigating patient and caregiver expectations for the current visit and facing every point during the examination represents a priority to make communication between patient and health care practitioner (HCP) stronger and more efficient (data from question two). However, only five (25%) specialists considered patient participation in the care pathway to be the main strength of their unit to pursue patient-focused care (Table 2).

Table 2.

Distribution of the responses to question seven provided by the clinicians, oncologists, and radiotherapists involved in the online survey.

However, most of the interviewees, responding to Question four, aimed to improve dialogue skills and patient management (Table 3).

Table 3.

Distribution of the responses to question four provided by the clinicians, oncologists, and radiotherapists involved in the online survey.

However, replying to question five, most clinicians (10 out of 19) thought that overcrowding and lack of time represent the main weaknesses in seeking patient-focused care while doing daily work. Eight of nineteen physicians (40%) thought that staff and equipment shortages inhibit empathic communication with patients in daily practice (question six). Answering question eight, the lack of time represents the weakness of the unit to pursue a patient-focused care for 13 out 19 (70%) participants in the survey. Consequently, regarding question nine, 12 of the 19 (65%) doctors interviewed believed that the principal objectives not reached are: taking time listening to the patient more than talking, and the ability to investigate patient doubts and anxieties. Open multidisciplinary confrontation and dialogue skills with patients and caregivers represent an aspect that clinicians would like to improve during daily clinical practice, as evidenced by the responses provided in the questionnaire. Eleven out nineteen physicians (58%) have chosen this option in answering question ten. However, as requested in question one, only five (25%) specialists considered “open communication” to be the most relevant need for patients with metastatic and/or recurrent H&N cancer. Instead, the majority continue to consider as a priority the need for nutritional counseling and pain therapy. The counseling and effective communication with the multidisciplinary approach represented the most peculiar topics for almost all interviewees in relation to the treatment of H&N advanced cancer, as shown in the answers to question 12 of the questionnaire. Eleven (60%) respondents to question 11 continued to consider the multidisciplinary approach as the most relevant topic in H&N cancer therapy, but only a minority, 8 out 19, thought that this approach cannot be pursued without effective counseling and communication with the patient and their caregivers (question 13). Fourteen responders out of nineteen clinicians involved declared that they use counseling techniques more than enough in clinical practice in answering question 14. Fourteen out of nineteen (74%) of the interviewees considered themselves at least partially satisfied with their daily work in respect to the interaction with the patient.

4. Discussion

Squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck remains a challenging clinical problem, with half a million new cases annually worldwide. Despite the recent development of new therapeutic options such as immunotherapy, patients with advanced disease still have low chances of being cured with current therapies [15].

Several studies and research have established that H&N cancer care provided through an integrated multidisciplinary team (MDT) approach determines improved patient outcome and better survival rates [7,16]. This innovative approach could increase efficiency in care delivery, reduce costs, and shorten hospital stay [17,18]. This core of the approach is represented by the exchange of information and dialogue between the various professionals involved in the treatment pathway.

In this setting, showing respect for the patient’s preferences and ensuring a better quality of life represent today the first aims that the doctor must pursue. This should pass through a shared communication obtained by listening to the preferences and needs of the patient [19]. Effective communication for cancer patients can meet information needs, reduce caregiver burden, improve physical and mental health, and promote intimacy. However, cancer patients and/or caregivers have different communication needs in terms of target, content, style, and communication timing. Data have suggested that communication preferences are related to factors such as demographics and ethnic origin [20].

In recent decades, attention has focused on efforts to improve doctor–patient communication, believing that such improvements would improve quality of care and patient outcomes [21,22]. Almost all specialists who participated in the survey confirmed that they are knowledgeable about the techniques of counseling; however, they claim to apply these counseling skills only partially, attributing the greatest difficulty to the limited time available in daily clinical practice.

All participants recognized the importance and priority of the multidisciplinary approach for the treatment of these tumors. However, they confirmed the presence of a series of obstacles that actually limit its application, including some difficulties in open communication. The dialogue between physicians and patients is the core of quality health care. It is essential that patient values are respected, and it is important to obtain patient preferences and goals [23].

The results of a recent study highlight the importance of exploring the thoughts and needs of patients, in order to enhance patient-centered care. Patients with head and neck cancer found it important to receive information on their life expectancy [24]. Professionals with better communication and interpersonal skills provide better support to their patients. The current productivity-oriented practice environment also presents barriers to effective communication; the experts involved in this observational survey confirmed the presence of several obstacles that slow the adequate development and application of counseling techniques, such as overcrowding and lack of time, but also internal conflicts and lack of appropriate knowledge about counseling. These original results were obtained on a representative but limited sample of medical oncologists and radiotherapists operating in some centers of Southern Italy, who are daily involved in the treatment of patients with SSCHN. The limited number of professionals involved in the present survey was due to the absence in some regions in Southern Italy of specialistic centers with a consolidated experience in the management of SSCHN. In particular, frequently they do not have all the needed professional skills, and some of them do not have a decisional network to take care of patients. In other cases, the centers or the professionals involved have a recent and unconsolidated experience in this specific field of oncological care. However, this information cannot be considered statistically significant and confirmation is needed from an even greater number of clinicians.

5. Conclusions

The results of the present survey confirm that oncology physicians tend to have a good perception of the communication skills of their colleagues, and they are generally satisfied with their work in relation to communication with patients. Several improvements in H&N cancer treatment recall a greater expectation of collaborative decision making, with professionals and patients participating as partners to achieve an agreement on goals in accordance with personal beliefs, values, and attitudes.

The survey, although it involved a limited number of specialists, highlighted that there is a need for greater communication both by the patient and by the doctor. In this field, the need to have specific training to improve the level of empathy is clear. The participants underlined how clinical practice and excessive work take away precious time from honest and constructive communication. Lack of staff and lack of time still represent barriers not only for a multidisciplinary approach but also for communication. This survey confirmed that although head and neck doctors will spend decades in medical education and advanced training to learn interventions, communication skills and instructional sessions are generally not considered of similar value.

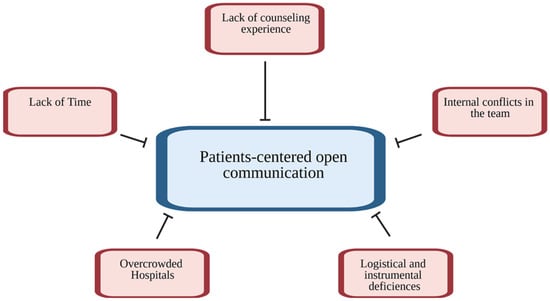

When talking about critical topics, such as advanced cancer, therapeutic options including immunotherapy or radiation therapy, and possible end-of-life decisions, patients want doctors to tell them honestly about their condition. Actual obstacles limit communication and make these decisions more difficult and often incomprehensible. However, the present survey showed that a frank and complete communication between doctor and patient continues to be hindered by various factors, only partially related to clinics (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Major barriers for patient-centered care.

For most of the clinicians involved, open communication objectively represented a purpose to be achieved from now on, avoiding the existing logistic and organizational barriers. This confirms the request for training and professional updates aiming to improve the relationship with patients to better define their expectations and legitimate requests. This request was clear from the answers to question 12, where all of the participants asked for more training and updating on counseling and effective communication.

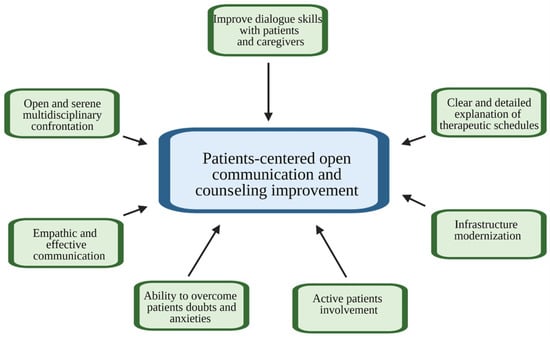

Several topical discussions must be improved with the sole goal of ensuring effective patient-centered communication. (Figure 2). Some of these elements are obtained only through complete communication between doctor and patient.

Figure 2.

Objectives to be chased to improve doctor–patient counseling.

The results of the questionnaires indicate that the lack of time represents a serious obstacle to the treatment of patients with head and neck cancer. Therefore, there is a need to implement solutions for the medical personnel involved in the treatment program for those patients in Southern Italy. The data confirm the importance of multidisciplinary confrontation and suggest the implementation of clear communication training with the stated aim of involving both the patient and their family in therapeutic choices.

This survey underlined how clinicians clearly understand the importance of involving the patient and their family in the treatment path with an active and leading role. To achieve this, the doctor cannot ignore the role of counseling for a clear and complete communication.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.A. (Raffaele Addeo) and R.A. (Raffaele Arigliani); methodology, R.A. (Raffaele Addeo); formal analysis, R.A. (Raffaele Addeo); investigation, R.A. (Raffaele Addeo); resources, R.A. (Raffaele Addeo), F.P., M.C., and M.F.; data collection, S.I.S.F., L.P., P.V., I.D.G., and M.F.; writing—original draft preparation, R.A. (Raffaele Addeo) and R.A. (Raffaele Arigliani); figure preparation, S.I.S.F.; writing—review and editing, R.A. (Raffaele Addeo), S.I.S.F., L.P., P.V., M.F., and F.P.; supervision, R.A. (Raffaele Addeo), R.A. (Raffaele Arigliani), and M.C.; project administration, R.A. (Raffaele Addeo) and M.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

The present study does not require formal ethic approval and/or acknowledgment by the local Ethics Committee ‘Comitato Etico Campania Centro’, in compliance with the Italian national regulation (“CIRCOLARE MINISTERIALE N. 6 DEL 2 SETTEMBRE 2002 pubblicata sulla G.U. n. 214 del 12 September 2002”). Written informed consent to participate was obtained from all participants.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- Argiris, A.; Karamouzis, M.V.; Raben, D.; Ferris, R.L. Head and neck cancer. Lancet 2008, 371, 1695–1709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schickedanz, A. Assessing and Improving Value in Cancer Care: Workshop Summary; The National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, S.M.; Clayton, J.M.; Hancock, K.; Walder, S.; Butow, P.N.; Carrick, S.; Currow, D.; Ghersi, D.; Glare, P.; Hagerty, R.; et al. A systematic review of prognostic/end-of-life communication with adults in the advanced stages of a life-limiting illness: Patient/caregiver preferences for the content, style, and timing of information. J. Pain Symptom Manag. 2007, 34, 81–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weeks, J.C.; Catalano, P.J.; Cronin, A.; Finkelman, M.D.; Mack, J.W.; Keating, N.L.; Schrag, D. Patients’ expectations about effects of chemotherapy for advanced cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2012, 367, 1616–1625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ribi, K.; Kalbermatten, N.; Eicher, M.; Strasser, F. Towards a novel approach guiding the decision-making process for anticancer treatment in patients with advanced cancer: Framework for systemic anticancer treatment with palliative intent. ESMO Open 2022, 7, 100496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hagerty, R.G.; Butow, P.N.; Ellis, P.M.; Dimitry, S.; Tattersall, M.H. Communicating prognosis in cancer care: A systematic review of the literature. Ann. Oncol. 2005, 16, 1005–1053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joosten, E.; de Weert, G.; Sensky, T.; van der Staak, C.; de Jong, C. Effect of shared decision-making on therapeutic alliance in addiction health care. Patient Prefer. Adherence 2008, 2, 277–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedland, P.L.; Bozic, B.; Dewar, J.; Kuan, R.; Meyer, C.; Phillips, M. Impact of multidisciplinary team management in head and neck cancer patients. Br. J. Cancer 2011, 104, 1246–1248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmid, M.; Giger, R.; Nisa, L.; Mueller, S.A.; Schubert, M.; Schubert, A.D. Association of Multiprofessional Preoperative Assessment and Information for Patients with Head and Neck Cancer with Postoperative Outcomes. JAMA Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2022, 148, 259–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hahlweg, P.; Hoffmann, J.; Harter, M.; Frosch, D.L.; Elwyn, G.; Scholl, I. In Absentia: An Exploratory Study of How Patients Are Considered in Multidisciplinary Cancer Team Meetings. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0139921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buss, M.K.; Lessen, D.S.; Sullivan, A.M.; Von Roenn, J.; Arnold, R.M.; Block, S.D. Hematology/oncology fellows’ training in palliative care: Results of a national survey. Cancer 2011, 117, 4304–4311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aslakson, R.A.; Wyskiel, R.; Shaeffer, D.; Zyra, M.; Ahuja, N.; Nelson, J.E.; Pronovost, P.J. Surgical intensive care unit clinician estimates of the adequacy of communication regarding patient prognosis. Crit. Care 2010, 14, R218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clover, A.; Browne, J.; McErlain, P.; Vandenberg, B. Patient approaches to clinical conversations in the palliative care setting. J. Adv. Nurs. 2004, 48, 333–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kane, H.L.; Halpern, M.T.; Squiers, L.B.; Treiman, K.A.; McCormack, L.A. Implementing and evaluating shared decision making in oncology practice. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2014, 64, 377–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szturz, P.; Vermorken, J.B. Management of recurrent and metastatic oral cavity cancer: Raising the bar a step higher. Oral Oncol. 2020, 101, 104492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.H.; Kung, P.T.; Tsai, W.C.; Tai, C.J.; Liu, S.A.; Tsai, M.H. Effects of multidisciplinary care on the survival of patients with oral cavity cancer in Taiwan. Oral Oncol. 2012, 48, 803–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prades, J.; Remue, E.; van Hoof, E.; Borras, J.M. Is it worth reorganising cancer services on the basis of multidisciplinary teams (MDTs)? A systematic review of the objectives and organisation of MDTs and their impact on patient outcomes. Health Policy 2015, 119, 464–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, T.E.; Janssen, A.; Harnett, P.; Museth, K.E.; Provan, P.J.; Hills, D.J.; Shaw, T. Embedding continuous quality improvement processes in multidisciplinary teams in cancer care: Exploring the boundaries between quality and implementation science. Aust. Health Rev. 2017, 41, 291–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saroa, O.; Molzahn, A.E.; Northcott, H.C.; Schmidt, K.; Ghosh, S.; Olson, K. A Survey of Information Needs and Preferences of Patients with Head and Neck Cancer. Oncol. Nurs. Forum 2018, 45, 761–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Luo, X.; Cao, Q.; Lin, Y.; Xu, Y.; Li, Q. Communication Needs of Cancer Patients and/or Caregivers: A Critical Literature Review. J. Oncol. 2020, 2020, 7432849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bredart, A.; Bouleuc, C.; Dolbeault, S. Doctor-patient communication and satisfaction with care in oncology. Curr. Opin. Oncol. 2005, 17, 351–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hesse, C.; Rauscher, E.A. The Relationships Between Doctor-Patient Affectionate Communication and Patient Perceptions and Outcomes. Health Commun. 2019, 34, 881–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beers, E.; Lee Nilsen, M.; Johnson, J.T. The Role of Patients: Shared Decision-Making. Otolaryngol. Clin. N. Am. 2017, 50, 689–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoesseini, A.; Dronkers, E.A.C.; Sewnaik, A.; Hardillo, J.A.U.; Baatenburg de Jong, R.J.; Offerman, M.P.J. Head and neck cancer patients’ preferences for individualized prognostic information: A focus group study. BMC Cancer 2020, 20, 399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).