Satisfaction with Telemedicine for Cancer Pain Management: A Model of Care and Cross-Sectional Patient Satisfaction Study

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Study Population

2.2. Questionnaire

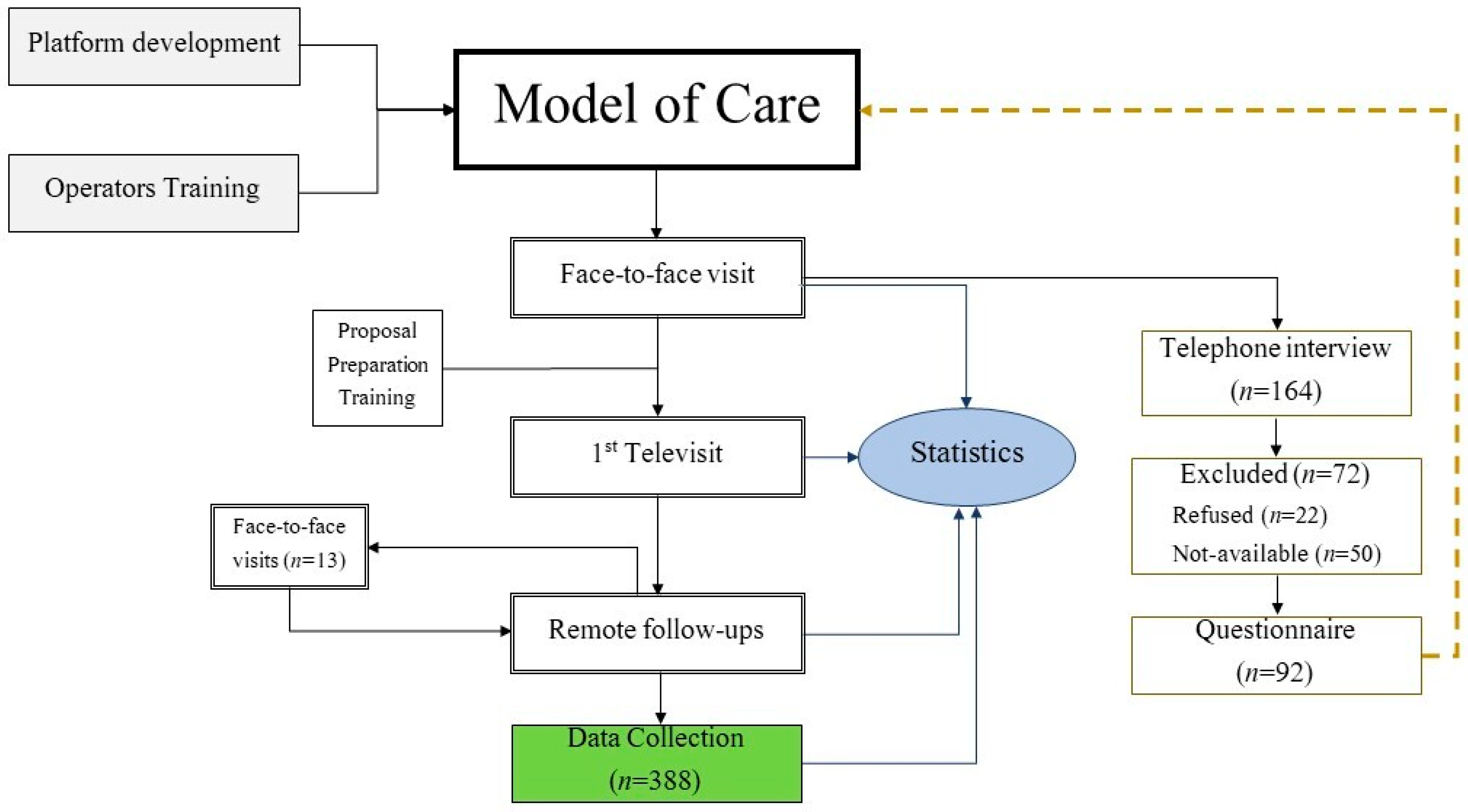

2.3. Model of Care

2.3.1. Information Technology (IT) Infrastructure

2.3.2. Operational Phases: The Hybrid Model of Care

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hincapié, M.A.; Gallego, J.C.; Gempeler, A.; Piñeros, J.A.; Nasner, D.; Escobar, M.F. Implementation and Usefulness of Telemedicine During the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Scoping Review. J. Prim. Care Community Health 2020, 11, 2150132720980612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jalilian, L.; Wu, I.; Ing, J.; Dong, X.; Sadik, J.; Pan, G.; Hitson, H.; Thomas, E.; Grogan, T.; Simkovic, M.; et al. Evaluation of Telemedicine Use for Anesthesiology Pain Division: Retrospective, Observational Case Series Study. JMIR Perioper Med. 2022, 5, e33926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Italian Ministry of Health. Organizational Guidelines on Home Care. Available online: https://www.gazzettaufficiale.it/eli/gu/2022/05/24/120/SG/html (accessed on 18 June 2022).

- Harnik, M.A.; Blättler, L.; Limacher, A.; Reisig, F.; Grosse Holtforth, M.; Streitberger, K. Telemedicine for chronic pain treatment during the COVID-19 pandemic: Do pain intensity and anxiousness correlate with patient acceptance? Pain Pract. 2021, 21, 934–942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rocque, G.B.; Halilova, K.I.; Varley, A.; Williams, C.P.; Taylor, R.A.; Masom, D.G.; Wright, W.J.; Partridge, E.E.; Kvale, E.A. Feasibility of a Telehealth Educational Program on Self-Management of Pain and Fatigue in Adult Cancer Patients. J. Pain Symptom Manag. 2017, 53, 1071–1078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cascella, M.; Marinangeli, F.; Vittori, A.; Scala, C.; Piccinini, M.; Braga, A.; Miceli, L.; Vellucci, R. Open Issues and Practical Suggestions for Telemedicine in Chronic Pain. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 12416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baughman, D.; Ptasinski, A.; Baughman, K.; Buckwalter, N.; Jabbarpour, Y.; Waheed, A. Comparable Quality Performance of Acute Low-Back Pain Care in Telemedicine and Office-Based Cohorts. Telemed. J. e-Health 2022. ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chua, I.S.; Zachariah, F.; Dale, W.; Feliciano, J.; Hanson, L.; Blackhall, L.; Quest, T.; Curseen, K.; Grey, C.; Rhodes, R.; et al. Early integrated telehealth versus in-person palliative care for patients with advanced lung cancer: A study protocol. J. Palliat. Med. 2019, 22 (Suppl. S1), S7–S19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parmanto, B.; Lewis, A.N., Jr.; Graham, K.M.; Bertolet, M.H. Development of the Telehealth Usability Questionnaire (TUQ). Int. J. Telerehabil. 2016, 8, 3–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterson, R. Constructing Effective Questionnaires. Available online: http://methods.sagepub.com/book/constructing-effective-questionnaires (accessed on 9 May 2022).

- Campania Region. Piattaforma Sinfonia. Available online: https://sinfonia.regione.campania.it (accessed on 20 May 2022).

- Pang, N.Q.; Lau, J.; Fong, S.Y.; Wong, C.Y.; Tan, K.K. Telemedicine Acceptance Among Older Adult Patients with Cancer: Scoping Review. J. Med. Internet Res. 2022, 24, e28724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knegtmans, M.F.; Wauben, L.S.G.L.; Wagemans, M.F.M.; Oldenmenger, W.H. Home Telemonitoring Improved Pain Registration in Patients with Cancer. Pain Pract. 2020, 20, 122–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.D. Telemedicine Workflow and Platform Options: What Would Work Well for Your Practice? Clin. Liver Dis. 2022, 19, 148–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cascella, M.; Miceli, L.; Cutugno, F.; Di Lorenzo, G.; Morabito, A.; Oriente, A.; Massazza, G.; Magni, A.; Marinangeli, F.; Cuomo, A.; et al. A Delphi Consensus Approach for the Management of Chronic Pain during and after the COVID-19 Era. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 13372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cascella, M.; Vittori, A.; Petrucci, E.; Marinangeli, F.; Giarratano, A.; Cacciagrano, C.; Tizi, E.S.; Miceli, L.; Natoli, S.; Cuomo, A. Strengths and Weaknesses of Cancer Pain Management in Italy: Findings from a Nationwide SIAARTI Survey. Healthcare 2022, 10, 441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexander, V.M.; Schelble, A.P.; Omurtag, K.R. Traits of patients seen via telemedicine versus in person for new-patient visits in a fertility practice. F S Rep. 2021, 2, 224–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odden, J.L.; Khanna, C.L.; Choo, C.M.; Zhao, B.; Shah, S.M.; Stalboerger, G.M.; Bennett, J.R.; Schornack, M.M. Telemedicine in long-term care of glaucoma patients. J. Telemed. Telecare 2020, 26, 92–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vosburg, R.W.; Robinson, K.A.; Gao, C.; Kim, J.J. Patient and Provider Satisfaction with Telemedicine in a Comprehensive Weight Management Program. Telemed. J. e-Health 2022, 28, 384–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crispo, A.; Montagnese, C.; Perri, F.; Grimaldi, M.; Bimonte, S.; Augustin, L.S.; Amore, A.; Celentano, E.; Di Napoli, M.; Cascella, M.; et al. COVID-19 Emergency and Post-Emergency in Italian Cancer Patients: How Can Patients Be Assisted? Front. Oncol. 2020, 10, 1571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gondal, H.; Abbas, T.; Choquette, H.; Le, D.; Chalchal, H.I.; Iqbal, N.; Ahmed, S. Patient and Physician Satisfaction with Telemedicine in Cancer Care in Saskatchewan: A Cross-Sectional Study. Curr. Oncol. 2022, 29, 3870–3880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsabeeha, N.H.M.; Atieh, M.A.; Balakrishnan, M.S. Older Adults’ Satisfaction with Telemedicine during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Systematic Review. Telemed. J. e-Health 2022. ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pakanati, V.; Raol, N.; Ching Siong, T.; Govil, N. Patient and physician satisfaction with telemedicine in pediatric otolaryngology. Int. J. Pediatr. Otorhinolaryngol. 2022, 156, 111097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kruse, C.S.; Krowski, N.; Rodriguez, B.; Tran, L.; Vela, J.; Brooks, M. Telehealth and patient satisfaction: A systematic review and narrative analysis. BMJ Open 2017, 7, e016242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhoden, P.A.; Bonilha, H.; Harvey, J. Patient Satisfaction of Telemedicine Remote Patient Monitoring: A Systematic Review. Telemed. J. e-Health 2022. ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

|

|

|

|

|

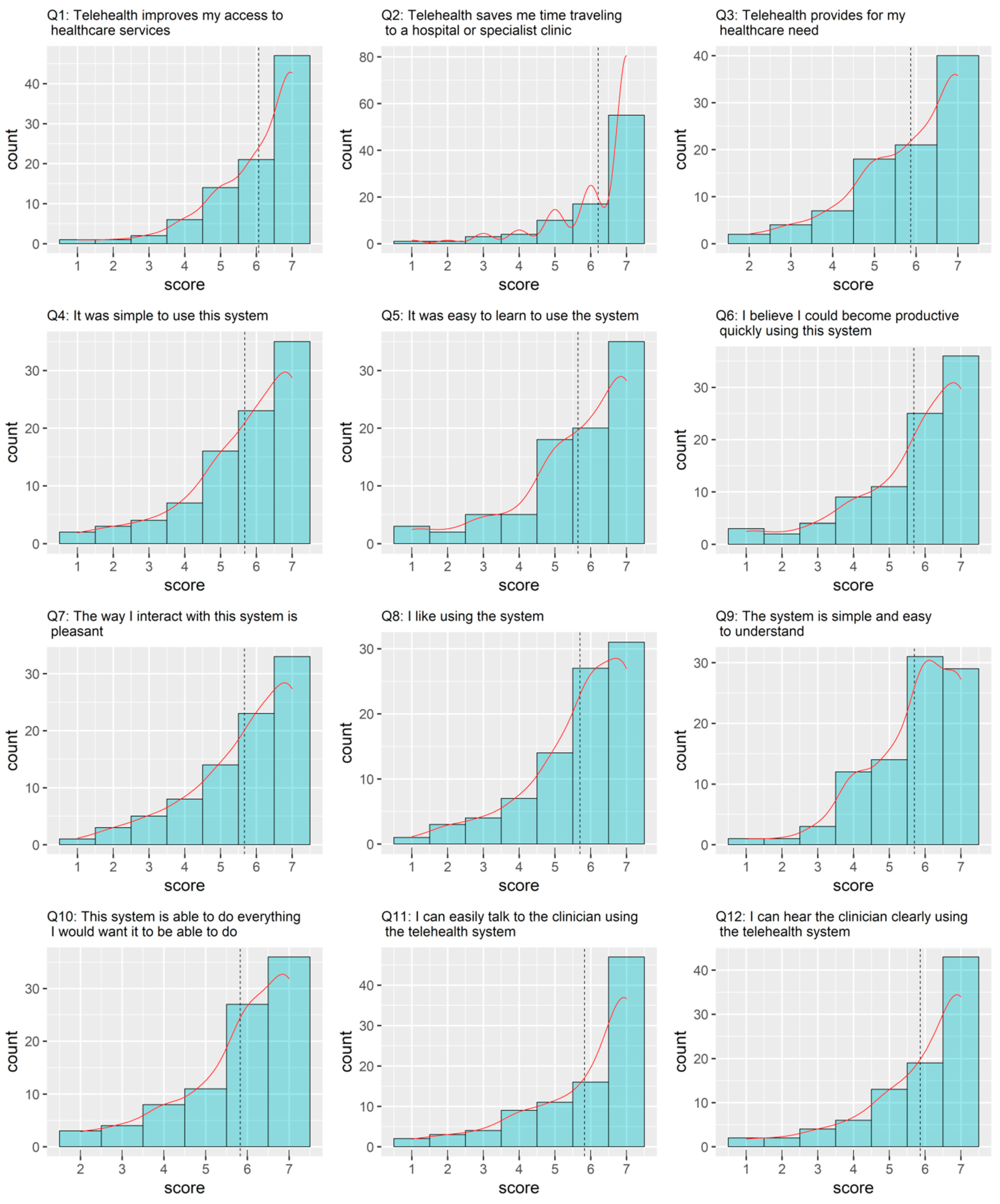

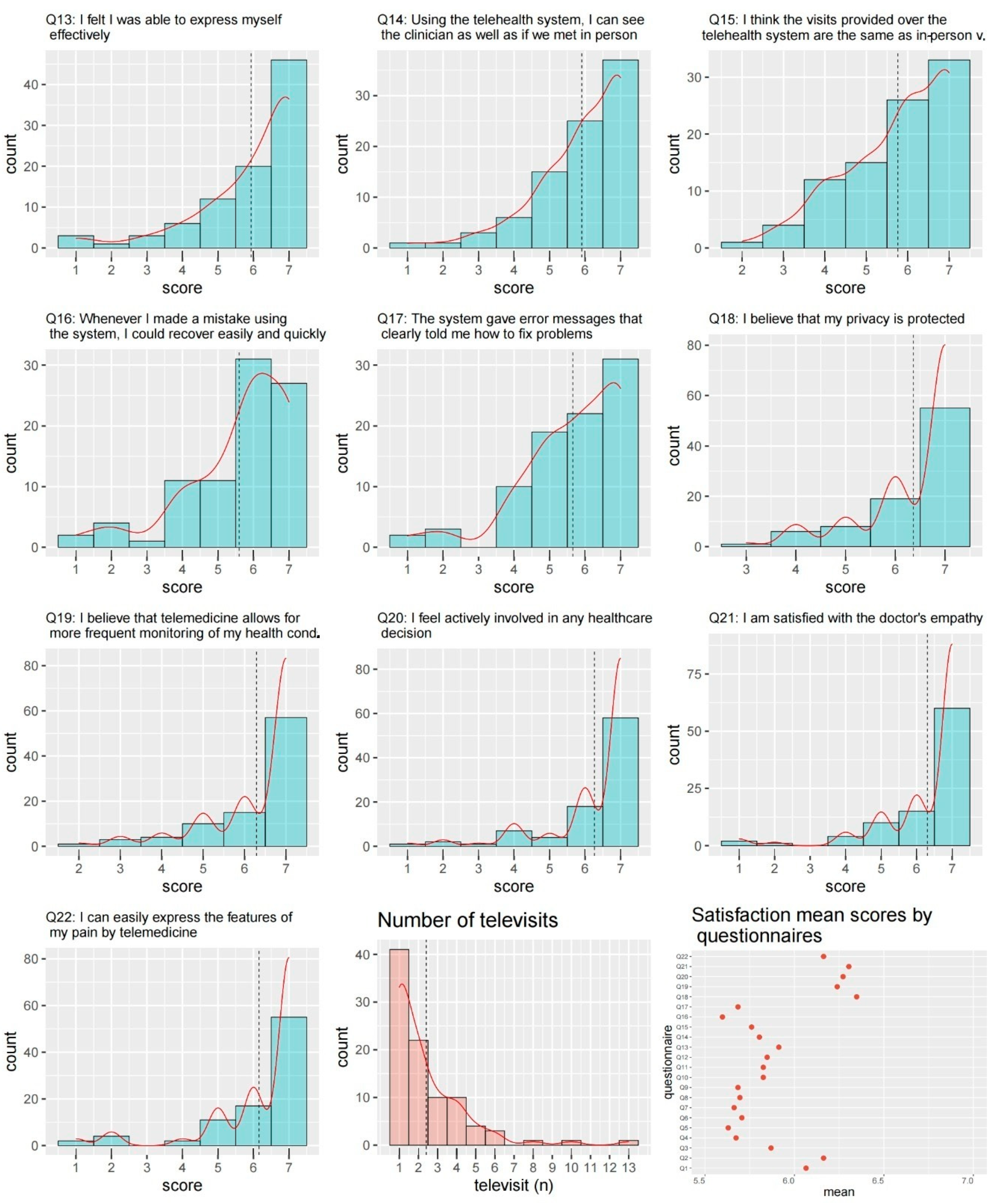

| 1 | Telehealth improves my access to healthcare services. |

| 2 | Telehealth saves me time traveling to a hospital or specialist clinic. |

| 3 | Telehealth provides for my healthcare need. |

| 4 | It was simple to use this system. |

| 5 | It was easy to learn to use the system. |

| 6 | I believe I could become productive quickly using this system. |

| 7 | The way I interact with this system is pleasant. |

| 8 | I like using the system. |

| 9 | The system is simple and easy to understand. |

| 10 | This system is able to do everything I would want it to be able to do. |

| 11 | I can easily talk to the clinician using the telehealth system. |

| 12 | I can hear the clinician clearly using the telehealth system. |

| 13 | I felt I was able to express myself effectively. |

| 14 | Using the telehealth system, I can see the clinician as well as if we met in person. |

| 15 | I think the visits provided over the telehealth system are the same as in-person visits. |

| 16 | Whenever I made a mistake using the system, I could recover easily and quickly. |

| 17 | The system gave error messages that clearly told me how to fix problems. |

| 18 | I believe that my privacy is protected. |

| 19 | I believe that telemedicine allows for more frequent monitoring of my health conditions. |

| 20 | I feel actively involved in any healthcare decision. |

| 21 | I am satisfied with the doctor–patient communication. |

| 22 | I can easily express the features of my pain through telemedicine. |

| Dropout | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Overall, N = 92 † | No, N = 84 † | Yes, N = 8 † | p-Value ‡ |

| Age | 0.2 | |||

| Mean (SD) | 64 (12) | 64 (12) | 57 (16) | |

| Median (IQR) | 66 (55, 73) | 66 (57, 73) | 52 (44, 72) | |

| Gender | 0.15 | |||

| F | 48 (100%) | 46 (96%) | 2 (4.2%) | |

| M | 44 (100%) | 38 (86%) | 6 (14%) | |

| Neoplasm | 0.6 | |||

| Other cancers | 40 (100%) | 36 (90%) | 4 (10%) | |

| Colon | 26 (100%) | 23 (88%) | 3 (12%) | |

| Breast | 15 (100%) | 15 (100%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Lung | 11 (100%) | 10 (91%) | 1 (9.1%) | |

| Metastatic status | 0.15 | |||

| No | 48 (100%) | 46 (96%) | 2 (4.2%) | |

| Yes | 44 (100%) | 38 (86%) | 6 (14%) | |

| ECOG-PS | >0.9 | |||

| ECOG < 3 | 49 (100%) | 45 (92%) | 4 (8.2%) | |

| ECOG = 3 | 43 (100%) | 39 (91%) | 4 (9.3%) | |

| Televisits (n) | 0.032 | |||

| n | 92 | 84 | 8 | |

| Mean (SD) | 2.4 (2) | 2.2 (1.9) | 4.1 (2.9) | |

| MED | >0.9 | |||

| ≤60 | 40 (100%) | 37 (92%) | 3 (7.5%) | |

| >60 | 52 (100%) | 47 (90%) | 5 (9.6%) | |

| IV-Morphine | 0.4 | |||

| No | 87 (100%) | 80 (92%) | 7 (8.0%) | |

| Yes | 5 (100%) | 4 (80%) | 1 (20%) | |

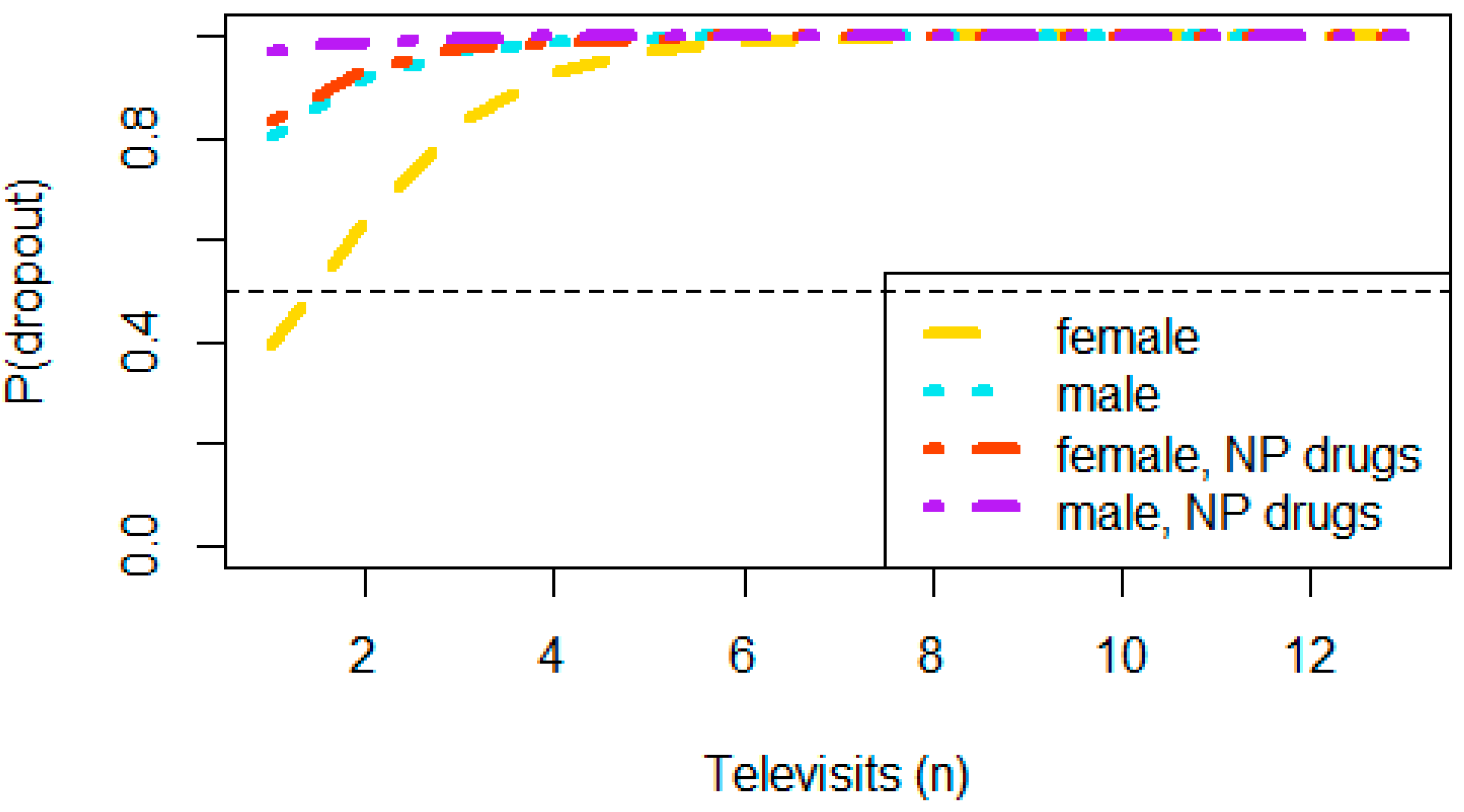

| NP Drugs | 0.074 | |||

| No | 52 (57%) | 50 (60%) | 2 (25%) | |

| Yes | 40 (43%) | 34 (40%) | 6 (75%) | |

| Characteristic | OR | 95% CI | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 0.94 | 0.87, 1.01 | 0.10 |

| Gender | |||

| F | - | - | |

| M | 6.36 | 0.99, 60.9 | 0.068 |

| Metastatic status | |||

| No | - | - | |

| Yes | 4.92 | 0.81, 51.1 | 0.12 |

| NP Drugs | |||

| No | - | - | |

| Yes | 7.68 | 1.25, 75.5 | 0.043 |

| Televisits (n) | 1.33 | 0.98, 1.84 | 0.062 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cascella, M.; Coluccia, S.; Grizzuti, M.; Romano, M.C.; Esposito, G.; Crispo, A.; Cuomo, A. Satisfaction with Telemedicine for Cancer Pain Management: A Model of Care and Cross-Sectional Patient Satisfaction Study. Curr. Oncol. 2022, 29, 5566-5578. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol29080439

Cascella M, Coluccia S, Grizzuti M, Romano MC, Esposito G, Crispo A, Cuomo A. Satisfaction with Telemedicine for Cancer Pain Management: A Model of Care and Cross-Sectional Patient Satisfaction Study. Current Oncology. 2022; 29(8):5566-5578. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol29080439

Chicago/Turabian StyleCascella, Marco, Sergio Coluccia, Mariacinzia Grizzuti, Maria Cristina Romano, Gennaro Esposito, Anna Crispo, and Arturo Cuomo. 2022. "Satisfaction with Telemedicine for Cancer Pain Management: A Model of Care and Cross-Sectional Patient Satisfaction Study" Current Oncology 29, no. 8: 5566-5578. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol29080439

APA StyleCascella, M., Coluccia, S., Grizzuti, M., Romano, M. C., Esposito, G., Crispo, A., & Cuomo, A. (2022). Satisfaction with Telemedicine for Cancer Pain Management: A Model of Care and Cross-Sectional Patient Satisfaction Study. Current Oncology, 29(8), 5566-5578. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol29080439