Outcomes of Geriatric Patients with Hepatocellular Carcinoma

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Ethics Statement

2.2. Study Population

2.3. Tumor Staging System

2.4. Inclusion Criteria

2.5. Exclusion Criteria

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

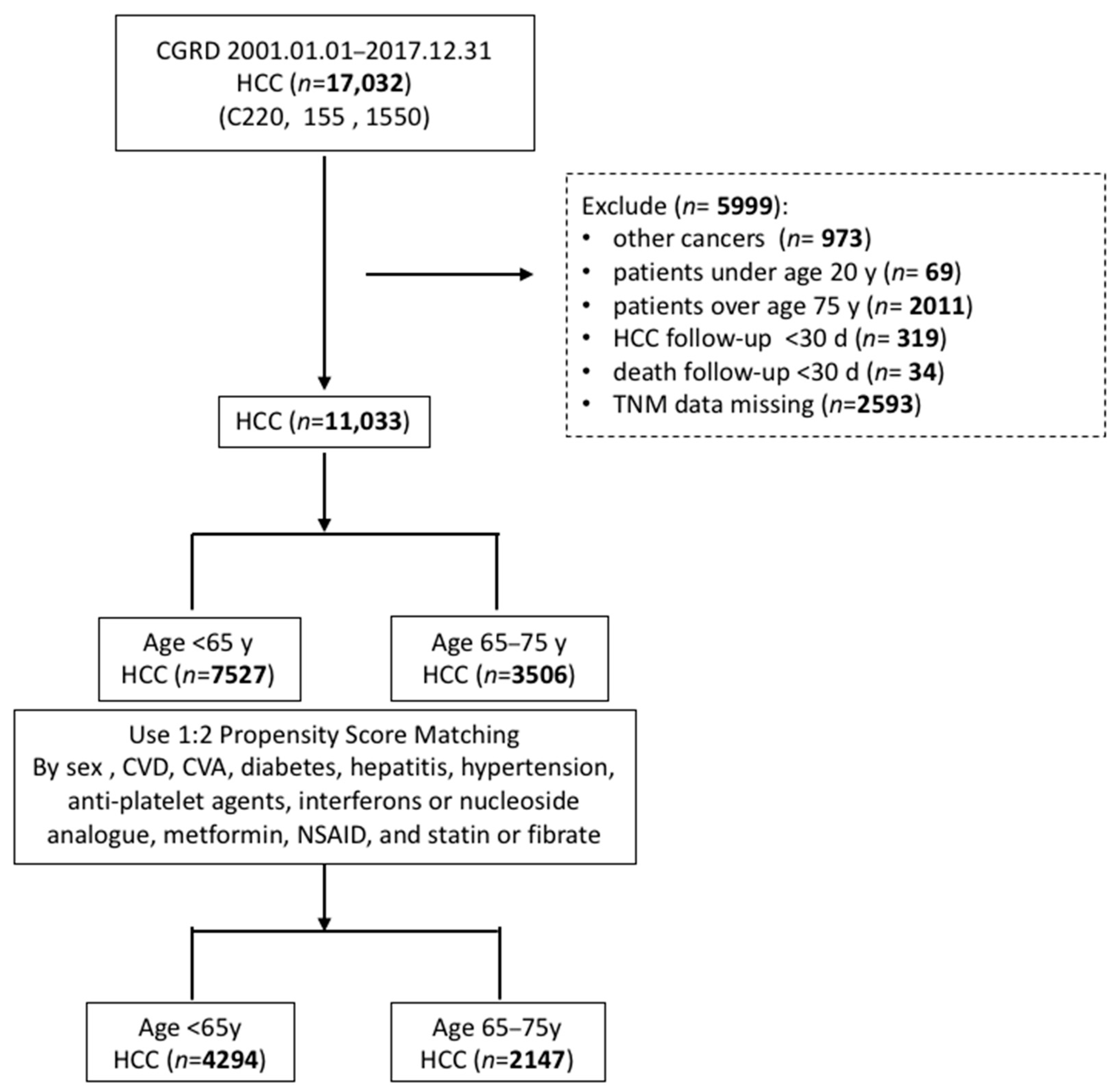

3.1. Patient Selection

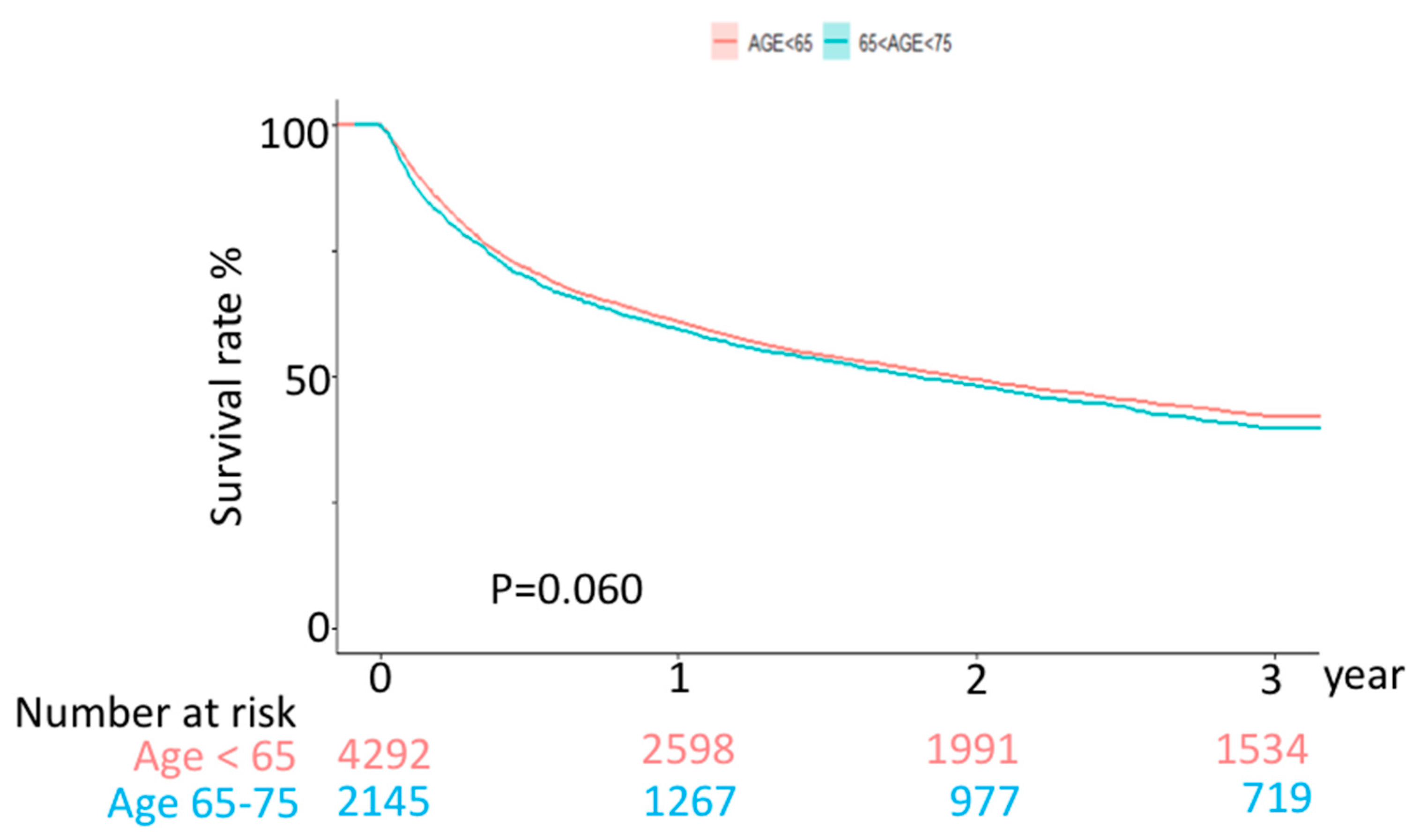

3.2. Outcome

3.3. Risk Factors by Multivariate Cox Regression Analysis

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Marosi, C.; Köller, M. Challenge of cancer in the elderly. ESMO Open 2016, 1, e000020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mittal, S.; Kramer, J.R.; Omino, R.; Chayanupatkul, M.; Richardson, P.A.; El-Serag, H.B.; Kanwal, F. Role of age and race in the risk of hepatocellular carcinoma in veterans with hepatitis b virus infection. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2018, 16, 252–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Woodrell, C.D.; Hansen, L.; Schiano, T.D.; Goldstein, N.E. Palliative Care for People with Hepatocellular Carcinoma, and Specific Benefits for Older Adults. Clin. Ther. 2018, 40, 512–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, H.; Wu, T.; Lu, Q.; Dong, J.; Ren, Y.-F.; Nan, K.-J.; Lv, Y.; Zhang, X.-F. Hepatocellular carcinoma in elderly: Clinical characteristics, treatments and outcomes compared with younger adults. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0184160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bruix, J.; Sherman, M. Management of hepatocellular carcinoma: An update. Hepatology 2011, 53, 1020–1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, C.-H.; Hsieh, S.-Y.; Chang, C.-C.; Wang, I.-K.; Huang, W.-H.; Weng, C.-H.; Hsu, C.-W.; Yen, T.-H. Hepatocellular carcinoma in hemodialysis patients. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 73154–73161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (Nhanes iii). Available online: http://www.Cdc.gov/nchs/about/major/nhanes/nh3data.Html (accessed on 7 May 2022).

- El Aziz, M.A.A.; Facciorusso, A.; Nayfeh, T.; Saadi, S.; Elnaggar, M.; Cotsoglou, C.; Sacco, R. Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors for Unresectable Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Vaccines 2020, 8, 616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizzo, A.; Ricci, A.D. PD-L1, TMB, and other potential predictors of response to immunotherapy for hepatocellular carcinoma: How can they assist drug clinical trials? Exp. Opin. Investig. Drugs 2022, 31, 415–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Lorenzo, S.; Tovoli, F.; Barbera, M.A.; Garuti, F.; Palloni, A.; Frega, G.; Garajovà, I.; Rizzo, A.; Trevisani, F.; Brandi, G. Metronomic capecitabine vs. best supportive care in Child-Pugh B hepatocellular carcinoma: A proof of concept. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 9997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, B.; Yang, X.-R.; Xu, Y.; Sun, Y.-F.; Sun, C.; Guo, W.; Zhang, X.; Wang, W.-M.; Qiu, S.-J.; Zhou, J.; et al. Systemic Immune-Inflammation Index Predicts Prognosis of Patients after Curative Resection for Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Clin. Cancer Res. 2014, 20, 6212–6222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hung, A.K.; Guy, J. Hepatocellular carcinoma in the elderly: Meta-analysis and systematic literature review. World J. Gastroenterol. 2015, 21, 12197–12210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, J.; Hurria, A. Determining chemotherapy tolerance in older patients with cancer. J. Natl. Compr. Cancer Netw. 2013, 11, 1494–1502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morio, J.; de Decker, L.; Paré, P.Y.; Launay, C.P.; Beauchet, O.; Annweiler, C. Comparison of hospital course of geriatric inpatients with or without active cancer: A bicentric case-control study. Geriatr. Psychol. Neuropsychiatr. Vieil 2018, 16, 241–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Donovan, A.; Leech, M. Personalised treatment for older adults with cancer: The role of frailty assessment. Tech. Innov. Patient Support Radiat. Oncol. 2020, 16, 30–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rozzini, R.; Frisoni, G.B.; Ferrucci, L.; Barbisoni, P.; Sabatini, T.; Ranieri, P.; Guralnik, J.M.; Trabucchi, M. Geriatric Index of Comorbidity: Validation and comparison with other measures of comorbidity. Age Ageing 2002, 31, 277–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quagliarello, V.J.; Malinis, M.F.; Chen, S.; Allore, H. Outcomes Among Older Adult Liver Transplantation Recipients in the Model of End Stage Liver Disease (MELD) Era. Ann. Transplant. 2014, 19, 478–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarour, L.R.; Billingsley, K.G.; Walker, B.S.; Enestvedt, C.K.; Orloff, S.L.; Maynard, E.; Mayo, S.C. Hepatic resection of solitary HCC in the elderly: A unique disease in a growing population. Am. J. Surg. 2019, 217, 899–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Famularo, S.; Di Sandro, S.; Giani, A.; Angrisani, M.; Lauterio, A.; Romano, F.; Gianotti, L.; De Carlis, L. The impact of age and ageing on hepatocarcinoma surgery: Short- and long-term outcomes in a multicentre propensity-matched cohort. Liver Int. 2019, 39, 894–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, J.H.; Kim, D.H.; Cho, E.; Jun, C.H.; Park, S.Y.; Cho, S.B.; Park, C.H.; Kim, H.S.; Choi, S.K.; Rew, J.S. Characteristics and Outcomes of Extreme Elderly Patients with Hepatocellular Carcinoma in South Korea. In Vivo 2019, 33, 145–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borzio, M.; Dionigi, E.; Parisi, G.; Raguzzi, I.; Sacco, R. Management of hepatocellular carcinoma in the elderly. World J. Hepatol. 2015, 7, 1521–1529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Desai, A.M.; Lichtman, S.M. Systemic therapy of non-colorectal gastrointestinal malignancies in the elderly. Cancer Biol. Med. 2015, 12, 284–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hsieh, C.-H.; Wei, C.-K.; Li-Ying, W.; Chang, C.-M.; Tsai, S.-J.; Wang, L.-Y.; Chiou, W.-Y.; Lee, M.-S.; Lin, H.-Y.; Hung, S.-K. Vascular invasion affects survival in early hepatocellular carcinoma. Mol. Clin. Oncol. 2015, 3, 252–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Age | <65 Years (N = 4294) | 65–75 Years (N = 2147) | p-Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex (n, %) | 0.7651 | ||||

| Male | 3521 | 54.67% | 1767 | 27.43% | |

| Female | 773 | 12.00% | 380 | 5.90% | |

| TNM stage (n, %) | 0.8804 | ||||

| I | 1395 | 21.66% | 697 | 10.82% | |

| II | 851 | 13.21% | 444 | 6.89% | |

| III | 1272 | 19.75% | 625 | 9.70% | |

| IV | 776 | 12.05% | 381 | 5.92% | |

| Comorbidities (n, %) | |||||

| CAD or CVA | 53 | 0.82% | 40 | 0.62% | 0.0461 |

| Diabetes | 751 | 11.66% | 373 | 5.79% | 0.9076 |

| Cirrhosis | 2787 | 43.27% | 1404 | 21.80% | 0.698 |

| Hepatitis | 257 | 3.99% | 126 | 1.96% | 0.8522 |

| Hypertension | 648 | 10.06% | 321 | 4.98% | 0.8824 |

| Medications use (n, %) | |||||

| Anti-platelet or Aspirin | 595 | 9.24% | 262 | 4.07% | 0.0655 |

| Interferons or nucleoside analogue | 1110 | 17.23% | 301 | 4.67% | <0.0001 |

| Metformin | 413 | 6.41% | 198 | 3.07% | 0.6092 |

| NSAID | 2904 | 45.09% | 1282 | 19.90% | <0.0001 |

| Statin or fibrate | 161 | 2.50% | 63 | 0.98% | 0.0924 |

| Laboratory data (median, Q1 to Q3) | |||||

| AFP (ng/mL) ≥ 100 | 34.16 | 7.24–535.5 | 28.15 | 6.13–304.2 | 0.0054 |

| ALT (U/L) ≥ 70 | 47.00 | 30–76 | 45.00 | 29–81 | 0.5408 |

| AST (U/L) ≥ 70 | 59.00 | 36–104 | 60.00 | 38–99 | 0.2155 |

| Albumin (g/L) > 3.0 | 3.90 | 3.3–4.4 | 3.80 | 3.27–4.23 | 0.589 |

| Creatinine (mg/dL) > 2.0 | 0.90 | 0.75–1.1 | 1.00 | 0.8–1.25 | 0.735 |

| Platelets (×1000/µL) ≥ 100 | 155.00 | 96–219 | 142.00 | 95–198 | <0.0001 |

| Total bilirubin (mg/dL) > 2.0 | 1.00 | 0.7–1.8 | 1.00 | 0.7–1.7 | 0.0514 |

| INR > 1.7 | 1.20 | 1.1–1.3 | 1.17 | 1.1–1.3 | 0.0242 |

| Tumor size (cm) > 3.0 | 2.00 | 1–3 | 2.00 | 1–3 | 0.6927 |

| SII (×109/L) > 610 | 452 | 223–960 | 409 | 219–907 | 0.6943 |

| HBsAg (+) (n, %) | 1034 | 46.70% | 398 | 17.98% | <0.0001 |

| HCV antibody (+) (n, %) | 535 | 17.13% | 495 | 15.85% | <0.0001 |

| MELD Score group (mean, sd) | 8.36 | 4.83 | 8.96 | 5.45 | <0.0001 |

| MELD Score group (n, %) | <0.0001 | ||||

| 1 | 3490 | 58.43% | 1621 | 27.14% | |

| 2 | 207 | 3.47% | 171 | 2.86% | |

| 3 | 285 | 4.77% | 199 | 3.33% | |

| 4 | 0 | 0.00% | 0 | 0.00% | |

| Laboratory data (n, %) | |||||

| AFP (ng/mL) ≥ 100 | 880 | 13.66% | 370 | 5.74% | 0.0018 |

| ALT (U/L) ≥ 70 | 1124 | 17.45% | 583 | 9.05% | 0.4018 |

| AST (U/L) ≥ 70 | 1584 | 24.59% | 773 | 12.00% | 0.4870 |

| Albumin (g/L) > 3.0 | 2532 | 39.31% | 1231 | 19.11% | 0.2108 |

| Creatinine (mg/dL) > 2.0 | 184 | 2.86% | 126 | 1.96% | 0.0051 |

| Platelets (×1000/µL) ≥ 100 | 2673 | 41.50% | 1276 | 19.81% | 0.0286 |

| Total bilirubin (mg/dL) > 2.0 | 823 | 12.78% | 346 | 5.37% | 0.0027 |

| INR > 1.7 | 124 | 1.93% | 40 | 0.62% | 0.0139 |

| Tumor size (cm) > 3.0 | 660 | 10.25% | 373 | 5.79% | 0.0389 |

| SII (×109/L) > 610 | 1097 | 26.22% | 494 | 11.81% | 0.0674 |

| Case Number | Death | Incidence (%) | Mean Following Year | Total Following Year | Incidence Rate (per 1000 Person-Year) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age < 65 years | 3 year | 4294 | 2439 | 56.80% | 1.680 | 7214.15 | 338.08 | ||

| Age 65–75 years | 3 year | 2147 | 1269 | 59.11% | 1.634 | 3508.38 | 361.70 | ||

| Crude HR | 95% CI | p-value | Adjusted HR | 95% CI | p-value | ||||

| Age < 65 years | |||||||||

| Age 65–75 years | 3 year | 1.023 | 0.891 | 1.175 | 0.7448 | 1.108 | 0.957 | 1.282 | 0.1695 |

| Univariate Cox Model | Multivariate Cox Model | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR | 95% CI | p-Value | HR | 95% CI | p-Value | |||

| Age 65–75 years | 1.0230 | 0.8910 | 1.1750 | 0.7448 | 1.1080 | 0.9570 | 1.2820 | 0.1695 |

| Sex (Male) | 1.2580 | 1.0450 | 1.5150 | 0.0154 | 1.5380 | 1.2630 | 1.8730 | <0.0001 |

| HBsAg (+) | 0.9710 | 0.8510 | 1.1080 | 0.6618 | ||||

| HCV antibody (+) | 0.9120 | 0.7920 | 1.0500 | 0.2012 | ||||

| CAD or CVA | 1.3580 | 0.8900 | 2.0730 | 0.1559 | ||||

| Diabetes | 0.9870 | 0.8450 | 1.1530 | 0.8690 | ||||

| Cirrhosis | 1.5330 | 1.3210 | 1.7800 | <0.0001 | 1.5950 | 1.3580 | 1.8730 | <0.0001 |

| Hepatitis | 0.4230 | 0.3190 | 0.5590 | <0.0001 | 0.5570 | 0.4190 | 0.7400 | <0.0001 |

| Hypertension | 0.7900 | 0.6690 | 0.9330 | 0.0054 | 0.9240 | 0.7750 | 1.1030 | 0.3827 |

| Anti-platelet or aspirin | 1.2760 | 1.0900 | 1.4930 | 0.0025 | 1.0390 | 0.8750 | 1.2330 | 0.6655 |

| Interferons or nucleoside analogue | 0.7530 | 0.6520 | 0.8690 | 0.0001 | 0.7810 | 0.6700 | 0.9110 | 0.0016 |

| Metformin | 0.8000 | 0.6430 | 0.9960 | 0.0458 | 0.9790 | 0.7800 | 1.2300 | 0.8563 |

| NSAID | 0.9210 | 0.8010 | 1.0590 | 0.2461 | ||||

| Statin or Fibrate | 0.4640 | 0.3280 | 0.6570 | <0.0001 | 0.5710 | 0.3950 | 0.8260 | 0.0029 |

| ALT (U/L) ≥ 70 | 1.4050 | 1.2180 | 1.6220 | <0.0001 | 1.3405 | 1.1364 | 1.5798 | 0.0005 |

| AST (U/L) ≥ 70 | 2.6890 | 2.3590 | 3.0640 | <0.0001 | 1.7870 | 1.5290 | 2.0900 | <.0001 |

| Albumin (g/L) > 3.0 | 0.5050 | 0.4390 | 0.5810 | <0.0001 | 0.7410 | 0.6360 | 0.8640 | 0.0001 |

| Total bilirubin (mg/dL) > 2.0 | 2.7600 | 2.3930 | 3.1830 | <0.0001 | 1.8520 | 1.5790 | 2.1720 | <.0001 |

| Creatinine (mg/dL) > 2.0 | 1.3610 | 1.0660 | 1.7360 | 0.0132 | 1.0380 | 0.7300 | 1.4750 | 0.8372 |

| Platelets (×1000/µL) ≥ 100 | 1.1320 | 0.9790 | 1.3100 | 0.0944 | ||||

| INR > 1.7 | 2.4380 | 1.7880 | 3.3230 | <0.0001 | 2.3280 | 1.6710 | 3.2430 | <0.0001 |

| SII (×109/L) > 610 | 2.8760 | 2.5190 | 3.2830 | <0.0001 | 1.5180 | 1.3110 | 1.7570 | <0.0001 |

| AFP (ng/mL) ≥ 100 | 2.4730 | 2.1700 | 2.8190 | <0.0001 | 1.6460 | 1.4280 | 1.8980 | <0.0001 |

| Tumor size (cm) > 3.0 | 3.1290 | 2.6160 | 3.7420 | <0.0001 | 0.7970 | 0.6560 | 0.9680 | 0.0224 |

| TNM stage | ||||||||

| II | 1.9930 | 1.5960 | 2.4880 | <0.0001 | 1.7430 | 1.3920 | 2.1840 | <0.0001 |

| III | 7.0920 | 5.9120 | 8.5090 | <0.0001 | 5.4860 | 4.4880 | 6.7050 | <0.0001 |

| IV | 13.0480 | 10.5260 | 16.1740 | <0.0001 | 9.6060 | 7.5020 | 12.2980 | <0.0001 |

| MELD Score group | ||||||||

| 2 | 1.6570 | 1.3040 | 2.1060 | <0.0001 | 1.3970 | 1.0920 | 1.7870 | 0.0079 |

| 3 | 1.8270 | 1.5160 | 2.2010 | <0.0001 | 1.6780 | 1.2770 | 2.2040 | 0.0002 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lee, C.-H.; Yen, T.-H.; Hsieh, S.-Y. Outcomes of Geriatric Patients with Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Curr. Oncol. 2022, 29, 4332-4341. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol29060346

Lee C-H, Yen T-H, Hsieh S-Y. Outcomes of Geriatric Patients with Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Current Oncology. 2022; 29(6):4332-4341. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol29060346

Chicago/Turabian StyleLee, Chern-Horng, Tzung-Hai Yen, and Sen-Yung Hsieh. 2022. "Outcomes of Geriatric Patients with Hepatocellular Carcinoma" Current Oncology 29, no. 6: 4332-4341. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol29060346

APA StyleLee, C.-H., Yen, T.-H., & Hsieh, S.-Y. (2022). Outcomes of Geriatric Patients with Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Current Oncology, 29(6), 4332-4341. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol29060346