Operationalizing Leadership and Clinician Buy-In to Implement Evidence-Based Tobacco Treatment Programs in Routine Oncology Care: A Mixed-Method Study of the U.S. Cancer Center Cessation Initiative

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Data Collection

2.2.1. Quantitative Data

2.2.2. Qualitative Data

2.3. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Cancer Center and Tobacco Treatment Program Characteristics

3.2. Operationalizing Leadership Buy-In for Initiating and Sustaining Program Implementation

3.2.1. Engaging Leadership

“The buy-in from the cancer center director was, I think, a critical step in getting administration onboard. And then once administration was onboard, the [human resources] staff were also willing to work with us. Although the time pressures and demands on the EHR staff on the numerable other things that they need to be collecting, I think, puts a little bit of a pressure on this”.-Respondent 10, Center 8

“As we were able to get buy-in from the cancer center leadership, the amount of support seemed to move, and the support from the administrative people and from both [hospital] administration and our own departmental administration in being able to do simple things as find the space around the clinic and work out billing issues, all of that moved much faster once we had buy-in from the cancer center leadership, knowing that this was something that was important to the cancer center”.-Respondent 15, Center 11

“One of the things that hurt us a lot here is that during the past two years, we have gone through a lot of changes and transition in leadership. So, every time we have a meeting with leadership members, by the time we go back, the [previous leadership is] not there or they have forgotten […] Every time, it was like starting from scratch, and a new approval is required from someone that we never heard of before”.-Respondent 6, Center 5

3.2.2. Requesting Access to Resources

“We need leadership to provide resources. We need institutional support for these two full-time positions and to cover nicotine replacement therapy and to cover the space”.-Respondent 1, Center 1

“…biggest test of this program going forward is, Do we have enough staff? We’ll find out very quickly. […] For now, we’ll get the main leadership buy-in to go to their faculty meetings, go to their nurse meetings. That’s basically going to be a full-time job for all of probably January and February”.-Respondent 28, Center 9

“…like our quarterback in the IT world. […] He just knows who to talk to. They had their annual system-wide IT meeting [IT Director] invited us to present about this program because he noted IT people usually work behind the scenes. They don’t always learn how their work impacts patient care. After the presentation, his words literally were, ‘My inbox is flooded with people wanting to know how they can get involved in this project’”.-Respondent 8, Center 6

“The director of the ambulatory operations in our cancer clinics controls the space in our hematology-oncology clinics, which is where they have like a rotating schedule of space that [the tobacco treatment specialist] can use. If it becomes a problem, she will reach out very practically and let him know like, ‘Hey, this is what happened today’. […] They’re supporting us in finding that space. […] We have her set up to have a mobile office capability [with a] laptop. [Cancer center director] got her a cellphone for use inhouse”.-Respondent 7, Center 6

3.2.3. Leveraging NCI Support to Build Leadership Interest in TTPs

“… I’ve been doing this for a really long time and have had a very hard time convincing people that tobacco dependence services are a critical part of a health system’s role. As soon as the NCI spoke up, that changed”.-Respondent 21, Center 15

“The NCI being willing to be involved in this and to put in, even if only a small amount of money to get this jump started, is a very big deal. […] Without that, we wouldn’t have seen the program success that has happened in this past year. Now I’m fully confident that we can continue to keep this up and running over the next years to decades”.-Center 8, Respondent 10

“We had a long, arduous negotiation with the hospital over making good on their commitment in the proposal to hire a [tobacco treatment specialist]. […] It required the addition of an FTE to their hard budget…to absorb the people who had already been hired and had been paid for four years on grant funds. It’s just, you know, anything they don’t have to, if they can’t get reimbursement and it’s going to cost them money, they’re skeptical”.-Respondent 3, Center 2

“We knew we would have to have [cancer center administrative and clinic directors] on board. […] It’s really not hard to sell treating tobacco [dependence] to oncologists, you know, at least in the head-nod version of doing it. Now, when it comes to the wallet version, I’m not so sure”.-Respondent 16, Center 12

3.3. Operationalizing Clinician and Staff Buy-In to Refer Patients and Deliver Treatment

3.3.1. Designating Program Champions

“The cancer clinicians are so consumed by the active treatment, they weren’t considering tobacco as part of treatment. This project is a tremendous opportunity to change that culture […] When this project came up, I said, ‘[champion name], you seem to get it, and you seem to be a perfect person for this sort of project.’ […] There was no question she is someone who was able to have relationships and come as an insider and bring this part in to start changing the culture”.-Respondent 23, Center 16

“…was really instrumental in identifying a champion for the program. [We] said, ‘You know, who do you recommend?’ And he recommended two of the very best champions in the cancer center, one on the medical side, one on the radiation side, who have been part of this from the beginning”.-Respondent 2, Center 2

3.3.2. Identifying Education and Training Needs

“Some of the people that have been here for a very long time have kind of hardened to the idea that smoking is something that they’re going to be able to change in our cancer patient population and in our culture. They’re pessimistic, and it’s just not a priority”.-Respondent 15, Center 11

“One of the other challenges is just getting people to understand the importance of intervening early in a person’s cancer experience. […] They’re still worrying about, ‘Let’s get to survivorship, and then we’ll start talking about this,’ which the evidence doesn’t support that. I mean, they’re less likely to get to survivorship, is what we’ve been pointing out, if we wait until then”.-Respondent 1, Center 1

“…to increase awareness of the program and create a more personalized relationship with the oncologists to be able to get those referrals”.-Respondent 6, Center 5

“We were very fortunate in that we paired up with [other C3I center] to create the tobacco treatment specialist program, and now all of our providers go through that program. We provide them specialized training, which we’ve had to develop for medical providers, specialized training for behavioral providers, and then a lot of just hand holding as well”.-Respondent 9, Center 7

3.3.3. Ensuring Staff Roles and IT Systems Support TTP Workflows

“I think for us, the biggest problem is the rate at which the oncologists are canceling the [referral]. I think it’s upwards of two-thirds, so we’ve still got a long way to go. And many of them may be new patients or inpatients”.-Respondent 21, Center 15

“…would show the physicians the best practice advisory and orient them to how to prescribe. However, we’d say, ‘If you don’t want to prescribe, we’re happy to, but let’s set up [electronic] links so that we can see these patients’”.-Respondent 30, Center 20

“We don’t have an alert culture. Physicians ignore it anyway. I will admit to that also. You know how to bypass it, and you’ll just ignore it”.-Respondent 23, Center 16

“I was surprised how willing and how supportive [the IT staff] were in the process of getting providers engaged in the tobacco treatment program. [They pulled] some of the data on the Quality Oncology Practice Initiative, analyzed the workflows. They even made small tests of change to support implementation”.-Respondent 14, Center 10

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Talluri, R.; Domgue, J.F.; Gritz, E.R.; Shete, S. Assessment of Trends in Cigarette Smoking Cessation After Cancer Diagnosis Among US Adults, 2000 to 2017. JAMA Netw. Open 2020, 3, e2012164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Warren, G.W. Mitigating the adverse health effects and costs associated with smoking after a cancer diagnosis. Transl. Lung Cancer Res. 2019, 8, S59–S66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramaswamy, A.; Toll, B.A.; Chagpar, A.B.; Judson, B.L. Smoking, cessation, and cessation counseling in patients with cancer: A population-based analysis. Cancer 2016, 122, 1247–1253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Condoluci, A.; Mazzara, C.; Zoccoli, A.; Pezzuto, A.; Tonini, G. Impact of smoking on lung cancer treatment effectiveness: A review. Futur. Oncol. 2016, 12, 2149–2161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goldstein, A.O.; Ripley-Moffitt, C.E.; Pathman, D.E.; Patsakham, K.M. Tobacco Use Treatment at the U.S. National Cancer Institute’s Designated Cancer Centers. Nicotine Tob. Res. 2012, 15, 52–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Price, S.N.; Studts, J.L.; Hamann, H.A. Tobacco Use Assessment and Treatment in Cancer Patients: A Scoping Review of Oncology Care Clinician Adherence to Clinical Practice Guidelines in the U.S. Oncologist 2018, 24, 229–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Burris, J.L.; Borger, T.N.; Shelton, B.J.; Darville, A.K.; Studts, J.L.; Valentino, J.; Blair, C.; Davis, D.B.; Scales, J. Tobacco Use and Tobacco Treatment Referral Response of Patients with Cancer: Implementation Outcomes at a National Cancer Institute–Designated Cancer Center. JCO Oncol. Pract. 2021, 18, e261–e270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guzzo, T.J.; Hockenberry, M.S.; Mucksavage, P.; Bivalacqua, T.J.; Schoenberg, M.P. Smoking Knowledge Assessment and Cessation Trends in Patients with Bladder Cancer Presenting to a Tertiary Referral Center. Urology 2012, 79, 166–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Himelhoch, S.; Riddle, J.; Goldman, H.H. Barriers to Implementing Evidence-Based Smoking Cessation Practices in Nine Community Mental Health Sites. Psychiatr. Serv. 2014, 65, 75–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodgers-Melnick, S.N.; Hooper, M.W. Implementation of tobacco cessation services at a comprehensive cancer center: A qualitative study of oncology providers’ perceptions and practices. Support. Care Cancer 2021, 29, 2465–2474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rojewski, A.M.; Bailey, S.R.; Bernstein, S.L.; Cooperman, N.A.; Gritz, E.R.; Karam-Hage, M.A.; Piper, M.E.; Rigotti, N.A.; Warren, G.W. Considering systemic barriers to treating tobacco use in clinical settings in the United States. Nicotine Tob. Res. 2019, 21, 1453–1461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kilbourne, A.M.; Almirall, D.; Eisenberg, D.; Waxmonsky, J.; Goodrich, D.E.; Fortney, J.C.; Kirchner, J.E.; Solberg, L.I.; Main, D.; Bauer, M.S.; et al. Protocol: Adaptive Implementation of Effective Programs Trial (ADEPT): Cluster randomized SMART trial comparing a standard versus enhanced implementation strategy to improve outcomes of a mood disorders program. Implement. Sci. 2014, 9, 132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Greenhalgh, T.; Robert, G.; Macfarlane, F.; Bate, P.; Kyriakidou, O. Diffusion of Innovations in Service Organizations: Systematic Review and Recommendations. Milbank Q. 2004, 82, 581–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Gesthalter, Y.B.; Koppelman, E.; Bolton, R.; Slatore, C.G.; Yoon, S.H.; Cain, H.C.; Tanner, N.T.; Au, D.H.; Clark, J.A.; Wiener, R.S. Evaluations of Implementation at Early-Adopting Lung Cancer Screening Programs: Lessons Learned. Chest 2017, 152, 70–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Malley, D.; Hudson, S.V.; Nekhlyudov, L.; Howard, J.; Rubinstein, E.; Lee, H.S.; Overholser, L.S.; Shaw, A.; Givens, S.; Burton, J.S.; et al. Learning the landscape: Implementation challenges of primary care innovators around cancer survivorship care. J. Cancer Surviv. 2016, 11, 13–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Powell, B.J.; Waltz, T.J.; Chinman, M.J.; Damschroder, L.J.; Smith, J.L.; Matthieu, M.M.; Proctor, E.K.; Kirchner, J.E. A refined compilation of implementation strategies: Results from the Expert Recommendations for Implementing Change (ERIC) project. Implement. Sci. 2015, 10, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Croyle, R.T.; Morgan, G.D.; Fiore, M.C. Addressing a Core Gap in Cancer Care—The NCI Moonshot Program to Help Oncology Patients Stop Smoking. N. Engl. J. Med. 2019, 380, 512–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Cancer Center Cessation Initiative Coordinating Center and Expert Advisory Panel. Introduction to the Cancer Center Cessation Initiative Working Groups: Improving Oncology Care and Outcomes by Including Tobacco Treatment. J. Natl. Compr. Cancer Netw. 2021, 19, S1–S3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Angelo, H.; Rolland, B.; Adsit, R.; Baker, T.B.; Rosenblum, M.; Pauk, D.; Morgan, G.D.; Fiore, M.C. Tobacco Treatment Program Implementation at NCI Cancer Centers: Progress of the NCI Cancer Moonshot-Funded Cancer Center Cessation Initiative. Cancer Prev. Res. 2019, 12, 735–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- D’Angelo, H.; Hooper, M.W.; Burris, J.L.; Rolland, B.; Adsit, R.; Pauk, D.; Rosenblum, M.; Fiore, M.C.; Baker, T.B. Achieving Equity in the Reach of Smoking Cessation Services Within the NCI Cancer Moonshot-Funded Cancer Center Cessation Initiative. Health Equity 2021, 5, 424–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creswell, J.W.; Plano Clark, V.L. Designing and Conducting Mixed Methods Research, 2nd ed.; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Palinkas, L.A.; Horwitz, S.M.; Green, C.A.; Wisdom, J.P.; Duan, N.; Hoagwood, K. Purposeful Sampling for Qualitative Data Collection and Analysis in Mixed Method Implementation Research. Adm. Policy Ment. Health Ment. Health Serv. Res. 2015, 42, 533–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tashakkori, A.; Teddlie, C. Quality of inferences in mixed methods research: Calling for an integrative framework. Adv. Mix. Methods Res. 2008, 53, 101–119. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell, J.W.; Poth, C.N. Qualitative Inquiry and Research Design: Choosing among Five Approaches, 4th ed.; Sage Publications: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- QSR International Pty Ltd. NVivo; QSR International Pty Ltd.: Melbourne, Australia, 2020; Available online: https://wwwqsrinternationalcom/nvivo-qualitative-data-analysis-software/home (accessed on 14 January 2022).

- Saldaña, J. The Coding Manual for Qualitative Researchers; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh, H.-F.; Shannon, S.E. Three Approaches to Qualitative Content Analysis. Qual. Health Res. 2005, 15, 1277–1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bowman, C.; Luck, J.; Gale, R.C.; Smith, N.; York, L.S.; Asch, S. A Qualitative Evaluation of Web-Based Cancer Care Quality Improvement Toolkit Use in the Veterans Health Administration. Qual. Manag. Health Care 2015, 24, 147–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wood, K.; Giannopoulos, V.; Louie, E.; Baillie, A.; Uribe, G.; Lee, K.S.; Haber, P.S.; Morley, K.C. The role of clinical champions in facilitating the use of evidence-based practice in drug and alcohol and mental health settings: A systematic review. Implement. Res. Pract. 2020, 1, 2633489520959072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dudgeon, D.; King, S.; Howell, D.; Green, E.; Gilbert, J.; Hughes, E.; LaLonde, B.; Angus, H.; Sawka, C. Cancer Care Ontario’s experience with implementation of routine physical and psychological symptom distress screening. Psycho-Oncology 2012, 21, 357–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flanagan, M.E.; Ramanujam, R.; Doebbeling, B.N. The effect of provider- and workflow-focused strategies for guideline implementation on provider acceptance. Implement. Sci. 2009, 4, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

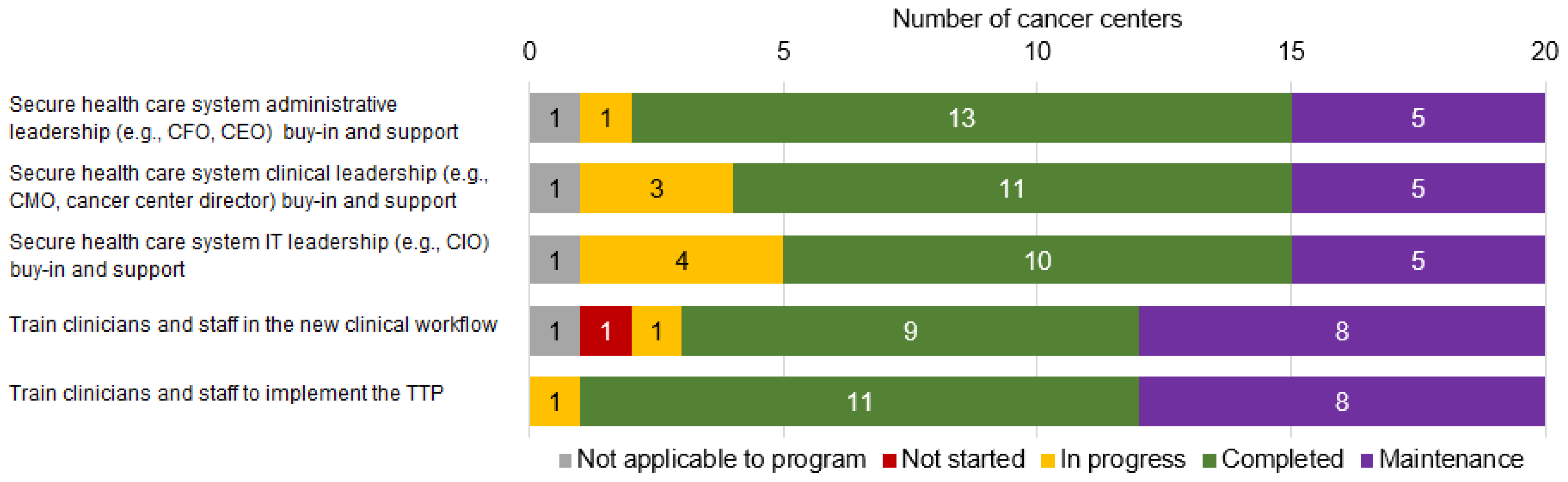

| Please Indicate the Status of Each of These Activities during This Reporting Period Using the Following Definitions: |

|---|

| Not started: Work has not begun on this activity. |

| In progress: Currently working/devoting significant personnel/resources towards the activity. |

| Completed: Goals of the activity have been met; no longer working towards the activity or devoting significant personnel/resources towards the activity. |

| Maintenance: Currently devote some time/resources to maintaining a previously completed activity. |

| 1. Secure health care system administrative leadership (e.g., CFO, CEO) buy-in and support |

| 2. Secure health care system clinical leadership (e.g., CMO, cancer center director) buy-in and support |

| 3. Secure health care system information technology leadership (e.g., CIO) buy-in and support |

| 4. Train clinicians and staff in the new clinical workflow |

| 5. Train clinicians and staff to implement the tobacco treatment program |

| For each statement, select the number that best indicates the extent to which your practice has or does the following things: The practice has engaged, ongoing champions. No extent (1) to Full extent (7) |

| Characteristic | Mean (n or %) | Range |

|---|---|---|

| Number of all patients served at cancer center | 21,220 | 507–95,149 |

| Number of reported patients who smoke | 1911 | 203–4561 |

| Screening rate | 93% | 49–100% |

| Smoking prevalence | 12% | 4–47% |

| Program reach among patients who smoke | 23% | 4–85% |

| Tobacco use treatment program time in operation | n | % |

| <2 years | 10 | 50% |

| ≥2 years or more | 10 | 50% |

| Referral strategies | n | % |

| Optional EHR referral | 13 | 65% |

| Clinician-initiated referral | 10 | 50% |

| Automatic EHR referral | 8 | 40% |

| Information given patient initiates | 8 | 40% |

| Evidence-based tobacco use treatment types offered | n | % |

| Individually delivered in-person counseling | 17 | 85% |

| Pharmacotherapy | 16 | 80% |

| Health system affiliated telephone-based counseling | 14 | 70% |

| Quitline via eReferral or fax | 14 | 70% |

| Point-of-care counseling | 10 | 50% |

| SmokefreeTXT referral | 9 | 45% |

| Group delivered in-person counseling | 5 | 25% |

| Web resource (e.g., Smokefree.gov) | 5 | 25% |

| TelASK or other IVR | 3 | 15% |

| Eligible patients | n | % |

| Outpatients | 19 | 95% |

| Inpatients | 7 | 35% |

| Family members | 4 | 20% |

| Engaged, ongoing champions integrated into program | n | % |

| Fully | 5 | 25% |

| Somewhat | 14 | 70% |

| Not at all | 1 | 5% |

| EMERGENT THEMES: HOW PROGRAM LEADS OPERATIONALIZED BUY-IN FOR TTPS IN CANCER CARE | CRITICAL COMPONENTS OF BUY-IN | RESULTS OF OBTAINING BUY-IN COMPONENTS |

|---|---|---|

| Operationalizing leadership buy-in for initiating and sustaining program implementation | ||

| Verbal support for the program |

|

| Communicating value of program, leveraging connections with other leaders within and outside of the cancer center | ||

Provision of financial resources for:

|

| |

| Commitment of office space |

| |

| Investment in IT and EHR systems changes and staff time to support new workflows and monitor TTP progress |

| |

| Operationalizing clinician and staff buy-in to refer patients and deliver treatment | ||

| Belief that TTP is necessary, valuable, and evidence-based |

|

| Belief that patients served at the cancer center will utilize the TTP | |

| Self-efficacy and willingness to refer patients to the TTP | |

| Self-efficacy and willingness deliver the TTP to patients with cancer | ||

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hohl, S.D.; Bird, J.E.; Nguyen, C.V.T.; D’Angelo, H.; Minion, M.; Pauk, D.; Adsit, R.T.; Fiore, M.; Nolan, M.B.; Rolland, B. Operationalizing Leadership and Clinician Buy-In to Implement Evidence-Based Tobacco Treatment Programs in Routine Oncology Care: A Mixed-Method Study of the U.S. Cancer Center Cessation Initiative. Curr. Oncol. 2022, 29, 2406-2421. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol29040195

Hohl SD, Bird JE, Nguyen CVT, D’Angelo H, Minion M, Pauk D, Adsit RT, Fiore M, Nolan MB, Rolland B. Operationalizing Leadership and Clinician Buy-In to Implement Evidence-Based Tobacco Treatment Programs in Routine Oncology Care: A Mixed-Method Study of the U.S. Cancer Center Cessation Initiative. Current Oncology. 2022; 29(4):2406-2421. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol29040195

Chicago/Turabian StyleHohl, Sarah D., Jennifer E. Bird, Claire V. T. Nguyen, Heather D’Angelo, Mara Minion, Danielle Pauk, Robert T. Adsit, Michael Fiore, Margaret B. Nolan, and Betsy Rolland. 2022. "Operationalizing Leadership and Clinician Buy-In to Implement Evidence-Based Tobacco Treatment Programs in Routine Oncology Care: A Mixed-Method Study of the U.S. Cancer Center Cessation Initiative" Current Oncology 29, no. 4: 2406-2421. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol29040195

APA StyleHohl, S. D., Bird, J. E., Nguyen, C. V. T., D’Angelo, H., Minion, M., Pauk, D., Adsit, R. T., Fiore, M., Nolan, M. B., & Rolland, B. (2022). Operationalizing Leadership and Clinician Buy-In to Implement Evidence-Based Tobacco Treatment Programs in Routine Oncology Care: A Mixed-Method Study of the U.S. Cancer Center Cessation Initiative. Current Oncology, 29(4), 2406-2421. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol29040195