Abstract

Gastroblastoma is an extremely rare stomach tumor that primarily presents in adolescent and early adulthood, with a biphasic cell morphology of epithelioid and spindle cells. In light of its similarity to other childhood blastomas, it has been named gastroblastoma. Few patients showed a potential of metastasis and recurrence, however, most of the reported cases were alive, with no evidence of the disease after surgical treatment. Commonly, MALAT1-GLI1 fusion has been considered to be the most relevant mutation. Herein, we present a case of an asymptomatic 58-year-old man who happened to find a submucosal gastric mass during a gastroscope and received endoscopic submucosal excavation (ESE). He turned out to have a gastroblastoma with a novel PTCH1::GLI2 fusion confirmed by Sanger sequencing. The patient was discharged two days after ESE without any complication and was recurrence-free during his one-year follow-up. According to the previous literature and our own experience, in cases with characteristic histopathology and immunohistochemistry patterns, a diagnosis of gastroblastoma should be considered even without a MALAT1-GLI1 fusion. Gastroblastoma pursues a favorable clinical outcome and endoscopic therapy could be an effective alternative treatment choice.

1. Introduction

Gastroblastoma, an extremely rare stomach tumor, is characterized by biphasic morphology with nests, sheets, tubules and cords of bland epithelioid cells, as well as clusters of spindle cells [1]. It usually lacks typical symptoms and may predominantly occur in younger patients with an onset age ranging between 9 and 74 years old (with a median age of 28 years old) and there is no apparent gender predilection. Most commonly seen in the antrum of the stomach, gastroblastoma often occurs in the gastric wall and inconstantly involves the submucosa, mucosa and subserosa, and may occasionally be transmural and give rise to peritoneal or lymph node metastases [2]. First described in 2009 by Miettinen et al. [3], gastroblastoma was first included in the fifth edition of the World Health Organization (WHO) classification of tumors of the digestive system in 2019. Due to its rarity, the etiopathogenesis and molecular alterations have been largely unknown, and consensus on the appropriate treatment has not been reached. Hitherto, there were only 15 cases being reported and MALAT1-GLI1 fusion was considered to be the most relevant mutation [4]. However, there was a lack of description of treatment for one patient, and all the other 14 patients took surgical treatment and most of them (79%, 11/14) had a good prognosis, without evidence of metastasis or recurrence. Herein, we report a gastroblastoma with a novel PTCH1::GLI2 fusion in a 58-year-old male who successfully underwent endoscopic submucosal excavation (ESE) with no metastasis or recurrence post-procedure during his one-year follow-up, and summarize the relevant literature. We hope this will enlighten the diagnosis and treatment choices for gastroblastoma patients in the future.

2. Case Presentation

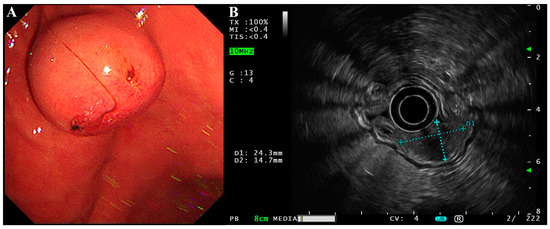

The patient was a 58-year-old male who happened to find a submucosal mass during an esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) in an annual routine examination. He had no discomfort or history other than hypertension and cholecystlithiasis, and came to our hospital for further consultation and examination. We found the mass at the lesser curvature of the gastric body (2.43 × 1.47 cm, Figure 1A) with an ulceration in the center of the mucosal surface. Endoscopic ultrasonography (EUS) was then performed using a circular array (EU-ME2 PREMIER PLUS with UE260-AL5, Olympus Optical Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan). The mass was hypoechoic and originated from the muscularis propria with a clear boundary and uniform internal echo (Figure 1B). There was no sign of infiltrative growth as the serosa layer of the lesion was intact. It was initially thought to be a gastrointestinal stromal tumor (GIST).

Figure 1.

EGD and EUS of the gastroblastoma. (A) EGD showed a submucosal mass with a small ulcer on its surface at the lesser curvature of the gastric body. (B) EUS showed the lesion was hypoechoic with a clear boundary and uniform internal echo. The lesion was approximately 2.43 × 1.47 cm in size and originated from the muscularis propria with an intact serosa layer.

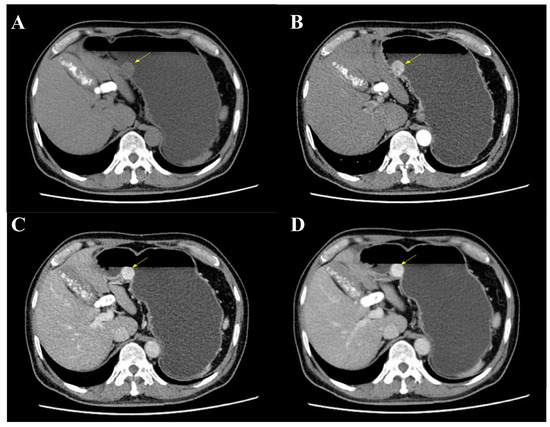

The mass was also revealed during an abdominal and pelvic enhanced computer tomography (CT), with a soft tissue density and a clear boundary (Figure 2A). It showed a significant enhancement during the arterial phase, portal venous phase and delayed phase (Figure 2B–D). A significantly increased enhancement of the mass was found during the portal venous phase, with a CT value of 156HU, and a glomangioma was suspected. With the exception of multiple gallstones, no lymph nodes or other abnormal phenomenon were found.

Figure 2.

Abdominal and pelvic enhanced CT. (A) CT showed a mass at the gastric body with a clear boundary and soft tissue density (yellow arrow). (B) The mass was enhanced during arterial phase (yellow arrow). (C) An increased enhancement of the mass was found during portal venous phase with a maximum CT value of 156HU (yellow arrow). (D) The mass was still enhanced during delayed phase (yellow arrow).

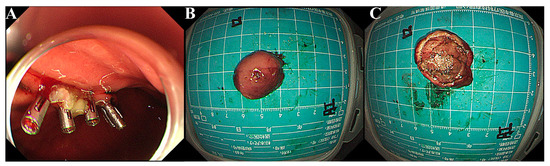

Physical examinations and laboratory tests of the patient showed no abnormalities. As his lesion had a clear boundary without infiltrative growth, the patient was admitted to our hospital for ESE using a GIF-Q260J with a LUCERA CV-290 electronic endoscope system (Olympus Optical Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan). ESE was successfully carried out and four clips were used to close the wound after complete excavation on 26 July 2021 (Figure 3A). It had a small ulcer on the surface and was solid, yellowish-pink with a pink-gray cut surface (Figure 3B,C).

Figure 3.

ESE and gross features of the mass. (A) After ESE’s en bloc excavation, four clips were used to close the incision. (B,C). Grossly, the mass was yellowish pink with a pink-gray cut surface.

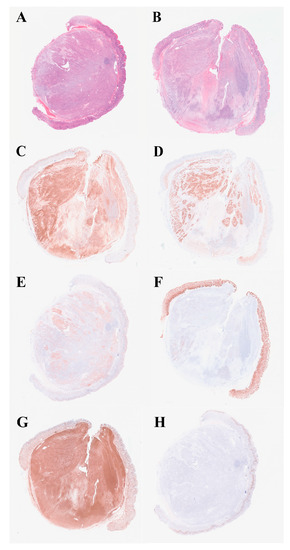

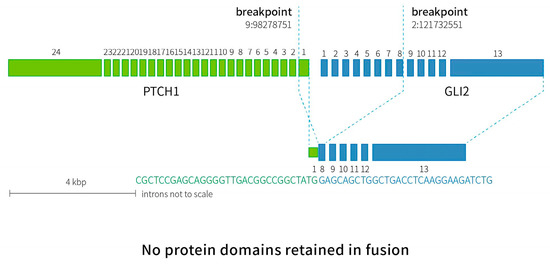

Histologic examination showed a biphasic pattern with relatively uniform spindle cells and epithelioid cells (Figure 4A,B, from different cut layer). As for immunohistochemistry (IHC), the lesion was positive for CD10 and vimentin in both the spindle cells and the epithelioid cells, while positive staining of CD56, S100 and EMA were mainly found in the epithelioid part (Figure 4C–G). Moreover, CD34, CD117, DOG-1, SMA, desmin, AE1/AE3, CAM5.2, CgA and Syn were negative. The Ki-67 index was approximately 5% (Figure 4H). Specific pathological details have been reported by our pathologist [5]. RNA was extracted from formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) specimens and RNA-based NGS was performed. A novel inter-chromosomal fusion, occurring between PTCH1 and GLI2 (ex1:ex8), was revealed. The fusion was subsequently confirmed by a reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR), followed by Sanger sequencing (Figure 5). Based on the above evidence, the patient was diagnosed with gastroblastoma. The patient recovered well without any complication and was discharged two days after the ESE procedure. During the one-year follow-up, with two EGD re-examinations and one CT scan, the patient had no evidence of recurrence or metastasis. Close follow-up was recommended.

Figure 4.

Hematoxylin-eosin staining (H&E) and IHC profile. (A,B) Histologically, the lesion had a biphasic pattern with spindle cells and epithelioid cells (in different layer, H&E, ×40). (C) CD10 was positive in both components (IHC, ×40). (D) CD56 was positive in the epithelioid part (IHC, ×40). (E) S100 was expressed in the epithelioid component (IHC, ×40). (F) EMA was focally expressed in the epithelioid part (IHC, ×40). (G) Vimentin was positive in both components (IHC, ×40). (H) Ki-67 index was approximately 5% (IHC, ×40).

Figure 5.

A diagram of RNA-based NGS results confirmed by Sanger sequencing. Inter-chromosomal fusion was identified between exon 1 of PTCH1 and exon 8 of GLI2. Breakpoint confirmed by Sanger sequencing was indicated by dotted lines (PTCH1 chr9:98278751, GLI2 chr2:121732551).

3. Discussion

Until the present case, there were only 12 articles, reporting 15 gastroblastoma cases. Patients usually presented with atypical symptoms including abdominal pain or melena. Various imaging examination showed that gastrbolastoma was usually hypoechogenic in EUS and with cystic components or uneven enhancement in CT. The detailed basic clinical and histological information is summarized in Table 1 and Table 2. All but one of the patients had surgery, with multiple options including tumorectomy, partial or subtotal gastrectomy by laparotomy, or laparoscopy based on the tumor size, location, infiltration and metastasis condition. Two patients also received extra treatment: one received chemotherapy before the surgery but had no response; the other received postoperative radiation. The clinical follow-up varied across different patients, with most of them (79%, 11/14) having no evidence of metastasis or recurrence (Table 3). Our patient was the only one treated with endoscopic therapy, and still had no metastasis or recurrence in the one-year follow-up following the procedure. Miettinen et al. proposed that gastroblastomas were lymphophilic tumors and indicated the importance of lymph node dissection [3]. However, these surgeries can cause extensive trauma with high risks and a long recovery time. As most of the gastroblastomas behave indolently, and considering most reported cases, as well as our case, had an excellent prognosis, we hope this endoscopic therapy will enlighten the future treatment of gastroblastoma patients, particularly for those who have small foci restricted to the submucosa without invasive growth.

Table 1.

Clinical Features of Reported Gastroblastomas.

Table 2.

Mutation and IHC patterns of gastroblastoma.

Table 3.

Treatment choice and related follow-up information of reported cases.

Gastroblastoma is solid and sometimes contains cystic hemorrhage. Histologically, the tumor has a biphasic epithelioid and spindle cell morphology. As its histomorphologic characteristic is similar to that of some blastomas occurring in other organ (especially pleuropulmonary blastoma and nephroblastoma), it was named after gastroblastoma by Miettinen et al. [3]. When comparing gastroblastomas to other blastomas which have immature components and definite malignant potentials, gastroblastomas tend to demonstrate an excellent prognosis, probably due to its developed architecture and low-grade cytologic features. It has been proposed that gastroblastoma may be better related to the spindle epithelioma of thymus and the demyelinating nested spindle cell tumor of liver rather than blastomas [2]. Due to its biphasic morphology, it is almost impossible to diagnose gastroblastoma by biopsy specimens. Its spindle components can be misdiagnosed as a low-grade sarcoma, the solid nested region as a neuroendocrine tumor, and the tubuloid structure as a form of epithelial neoplasm. By IHC, gastroblastoma seldom expresses markers that are usually positive in GISTs (c-KIT or CD117 and DOG-1), solitary fibrous tumors (CD34), nerve sheath tumors (S100), or mesothelial tumors (calretinin, CK5/6, WT-1). Neuroendocrine tumor markers (CgA and Syn) and smooth muscle tumor markers (SMA and desmin) are not usually expressed in gastroblastoma. Further main points of differential diagnosis are listed in Table 4. Notably, our case was positive for S100, which is not common in gastroblastomas. Nonetheless, it had a characteristic biphasic morphology, and its histopathology pattern and IHC features were relatively consistence with previous reports, which helped us reach the final diagnosis of gastroblatoma. As for a definite diagnosis of gastroblastoma, comprehensive evaluation of clinical and pathological features, including tumor origin, histomorphology, IHC patterns and mutation, should be considered.

Table 4.

Differential Diagnosis.

A recurrent MALAT1-GLI1 fusion has been detected in five cases of gastroblastoma (5/15 cases). In addition, it can also be involved in plexiform fibromyxomas (3/16 cases) [15]. Graham et al. summarized in their study that a reciprocal GLI1-MALAT1 fusion was found in two gastroblastoma cases and for the other two cases with a MALAT1-GLI1 fusion, MALAT1 exon1 was fused to GLI1 intron 5 to exon 12 and GLI1 exons 5–12, respectively [4]. MALAT1 (metastasis-associated lung adenocarcinoma transcript 1) is a long noncoding RNA, which is highly expressed in the nucleus of most cells and provides a strong promoter that drives GLI1 overexpression [16]. GLI1 (glioma-associated oncogene homologue 1) encodes a zinc-finger transcription factor in the Kruppel family proteins, and plays a vital role in the Sonic Hedgehog (Shh) pathway, as well as in proliferation, growth, angioinvasion, invasion, migration and cancer stem cell self-renewal in a variety of malignant tumors [17]. MALAT1-GLI1 fusion results in the overexpression of GLI1 and, in turn, the overexpression of GLI1 leads to the overexpression of several downstream targets, including PTCH1, VEGFA, SOX2 and CCND1. PTCH1 (transmembrane receptor Patched 1) is involved in cell proliferation and organization, and it is correlated with a copy number variation burden, tumor mutational burden (TMB) and loss of heterozygosity score [4]. PTCH1 and GLI family proteins are both involved in the Hedgehog-GLI (hh-GLI) pathway. Canonical activation of hh-GLI signaling is initiated when the secreted ligand binds to PTCH1, which derepresses SMO (G protein-couple receptor Smoothened) and leads to the activation of the GLI transcription factors (GLI1, 2, 3) [18]. Abnormal activation of hh-GLI has been implicated in a wide variety of tumors, such as those of the skin, brain, lungs, gastrointestinal, pancreas, prostate, breasts and ovaries [19]. Kim etal reported a recurrent FHL2-GLI2 fusion in a sclerosing stromal tumor, which resulted in the transcriptomic activation of the Shh pathway [20]. Punjabi et al. presented a high-grade uterine sarcoma case with a PAMR1::GLI1 fusion in which the Shh/GLI signaling pathway was involved [21]. A translocated ACTB-GLI1 fusion was reported by Ambrosio et al. in a patient with a malignant epithelioid neoplasm of the ileum [22]. The ubiquitously expressed ACTB activated GLI1 expression, where the Shh signaling pathway was involved in the tumorigenesis. As for our case, the gastroblastoma patient with a PTCH1::GLI2 fusion, we predicted that the Shh pathway was activated and an overexpression of GLI2 would be involved, similar to that of other GLI fusion tumors. The underlying mechanism and downstream targets require further study.

4. Conclusions

We report a gastroblastoma occurring in an adult with a novel PTCH1::GLI2 fusion. In cases with a characteristic histopathology and IHC patterns, a diagnosis of gastroblastoma should be considered, even without a MALAT1-GLI1 fusion. For this particular case, whose lesion was relatively small with a restricted growth, a therapeutic endoscopy was carried out and no evidence of metastasis or recurrence was indicated during the one-year follow-up. Combining the previous studies, it seems that this particular tumor possesses a favorable clinical outcome and prognosis, despite its adopted suffix “blastoma”. Additionally, endoscopic therapy could be an effective alternative choice for some gastroblastoma patients in the future.

Author Contributions

Y.L. served as the resident of the patient, collected related data, summarized the reported cases and wrote the manuscript; H.W. made the pathological diagnosis; X.W. and Q.W. performed EUS and ESE for the patient; Y.F. and Q.J. collected the follow-up data and participated in the literature review; Y.F. and Y.L. revised the manuscript; A.Y. conceived the study design and reviewed the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Key Clinical Specialist Construction Project (ZK108000), National High-Level Hospital Clinical Research Funding (2022-PUMCH-B-024) and CAMS Innovation Fund for Medical Sciences (CIFMS, 2022-I2M-C&T-B-012).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Committee of Peking Union Medical College Hospital, Peking Union Medical College and Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences, China (No.S-K2107, 20 May 2022).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from the patient involved in the study before examination, treatment and publishing.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank all of our colleagues in the medical and nursing team of the Gastroenterology Department.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Papke, D.J., Jr.; Hornick, J.L. Recent developments in gastroesophageal mesenchymal tumours. Histopathology 2021, 78, 171–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wey, E.A.; Britton, A.J.; Sferra, J.J.; Kasunic, T.; Pepe, L.R.; Appelman, H.D. Gastroblastoma in a 28-year-old man with nodal metastasis: Proof of the malignant potential. Arch. Pathol. Lab. Med. 2012, 136, 961–964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miettinen, M.; Dow, N.; Lasota, J.; Sobin, L.H. A distinctive novel epitheliomesenchymal biphasic tumor of the stomach in young adults (“gastroblastoma”): A series of 3 cases. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 2009, 33, 1370–1377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, R.P.; Nair, A.A.; Davila, J.I.; Jin, L.; Jen, J.; Sukov, W.R.; Wu, T.T.; Appelman, H.D.; Torres-Mora, J.; Perry, K.D.; et al. Gastroblastoma harbors a recurrent somatic MALAT1-GLI1 fusion gene. Mod. Pathol. 2017, 30, 1443–1452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, C.; Lu, J.; Wu, H. Case Report: Submucosal gastroblastoma with a novel PTCH1::GLI2 gene fusion in a 58-year-old man. Front. Oncol. 2022, 12, 935914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koo, S.C.; LaHaye, S.; Kovari, B.P.; Schieffer, K.M.; Ranalli, M.A.; Aldrink, J.H.; Michalsky, M.P.; Colace, S.; Miller, K.E.; Bedrosian, T.A.; et al. Gastroblastoma with a novel EWSR1-CTBP1 fusion presenting in adolescence. Genes Chromosomes Cancer 2021, 60, 640–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, W.G.; Zhuang, Y.; Li, M.; Zheng, F.; Zhong, A.J.; Wang, D.Q.; Wu, J.N. Gastroblastoma: Report of a case. Zhonghua Bing Li Xue Za Zhi 2020, 49, 761–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinto, D.N.; Ventura, J.; Gomes, D.; Brito, T.; Leite, M.; Monteiro, C.; Matos, C.; Fazeres, F.; Lopes, L.; Midões, A. Gastroblastoma described in adult patient. Int. J. Case Rep. Images 2019, 2019, 10. [Google Scholar]

- Castri, F.; Ravegnini, G.; Lodoli, C.; Fiorentino, V.; Abatini, C.; Giustiniani, M.C.; Angelini, S.; Ricci, R. Gastroblastoma in old age. Histopathology 2019, 75, 778–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Centonze, G.; Mangogna, A.; Salviato, T.; Belmonte, B.; Cattaneo, L.; Monica, M.A.T.; Garzone, G.; Brambilla, C.; Pellegrinelli, A.; Melotti, F.; et al. Gastroblastoma in Adulthood-A Rarity among Rare Cancers-A Case Report and Review of the Literature. Case Rep. Pathol. 2019, 2019, 4084196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toumi, O.; Ammar, H.; Korbi, I.; Ayed, M.; Gupta, R.; Nasr, M.; Salem, R.; Hadhri, R.; Zayed, S.; Noomen, F.; et al. Gastroblastoma, a biphasic neoplasm of stomach: A case report. Int. J. Surg. Case Rep. 2017, 39, 72–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, Y.; Zheng, J.; Zhu, H.; Dong, K.; Zheng, S.; Xiao, X.; Chen, L. Gastroblastoma in a 12-year-old Chinese boy. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Pathol. 2014, 7, 3380–3384. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Fernandes, T.; Silva, R.; Devesa, V.; Lopes, J.M.; Carneiro, F.; Viamonte, B. AIRP best cases in radiologic-pathologic correlation: Gastroblastoma: A rare biphasic gastric tumor. Radiographics 2014, 34, 1929–1933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shin, D.H.; Lee, J.H.; Kang, H.J.; Choi, K.U.; Kim, J.Y.; Park, D.Y.; Lee, C.H.; Sol, M.Y.; Park, J.H.; Kim, H.Y.; et al. Novel epitheliomesenchymal biphasic stomach tumour (gastroblastoma) in a 9-year-old: Morphological, ultrastructural and immunohistochemical findings. J. Clin. Pathol. 2010, 63, 270–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prall, O.W.J.; McEvoy, C.R.E.; Byrne, D.J.; Iravani, A.; Browning, J.; Choong, D.Y.; Yellapu, B.; O’Haire, S.; Smith, K.; Luen, S.J.; et al. A Malignant Neoplasm From the Jejunum With a MALAT1-GLI1 Fusion and 26-Year Survival History. Int. J. Surg. Pathol. 2020, 28, 553–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonescu, C.R.; Agaram, N.P.; Sung, Y.S.; Zhang, L.; Swanson, D.; Dickson, B.C. A Distinct Malignant Epithelioid Neoplasm With GLI1 Gene Rearrangements, Frequent S100 Protein Expression, and Metastatic Potential: Expanding the Spectrum of Pathologic Entities With ACTB/MALAT1/PTCH1-GLI1 Fusions. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 2018, 42, 553–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chetty, R. Gene of the month: GLI-1. J. Clin. Pathol. 2020, 73, 228–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, M.; Kicheva, A.; Ribeiro, A.; Blassberg, R.; Page, K.M.; Barnes, C.P.; Briscoe, J. Ptch1 and Gli regulate Shh signalling dynamics via multiple mechanisms. Nat. Commun. 2015, 6, 6709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pietrobono, S.; Gagliardi, S.; Stecca, B. Non-canonical Hedgehog Signaling Pathway in Cancer: Activation of GLI Transcription Factors Beyond Smoothened. Front. Genet. 2019, 10, 556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.H.; Da Cruz Paula, A.; Basili, T.; Dopeso, H.; Bi, R.; Pareja, F.; da Silva, E.M.; Gularte-Merida, R.; Sun, Z.; Fujisawa, S.; et al. Identification of recurrent FHL2-GLI2 oncogenic fusion in sclerosing stromal tumors of the ovary. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Punjabi, L.S.; Goh, C.H.R.; Sittampalam, K. Expanding the spectrum of GLI1-altered mesenchymal tumors-A high-grade uterine sarcoma harboring a novel PAMR1::GLI1 fusion and literature review of GLI1-altered mesenchymal neoplasms of the gynecologic tract. Genes Chromosomes Cancer 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ambrosio, M.; Virgilio, A.; Raffone, A.; Arena, A.; Raimondo, D.; Alletto, A.; Seracchioli, R.; Casadio, P. Malignant epithelioid neoplasm of the ileum with ACTB-GLI1 fusion mimicking an adnexal mass. BMC Womens Health 2022, 22, 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).