“Give My Daughter the Shot!”: A Content Analysis of the Depiction of Patients with Cancer Pain and Their Management in Hollywood Films

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Review Design

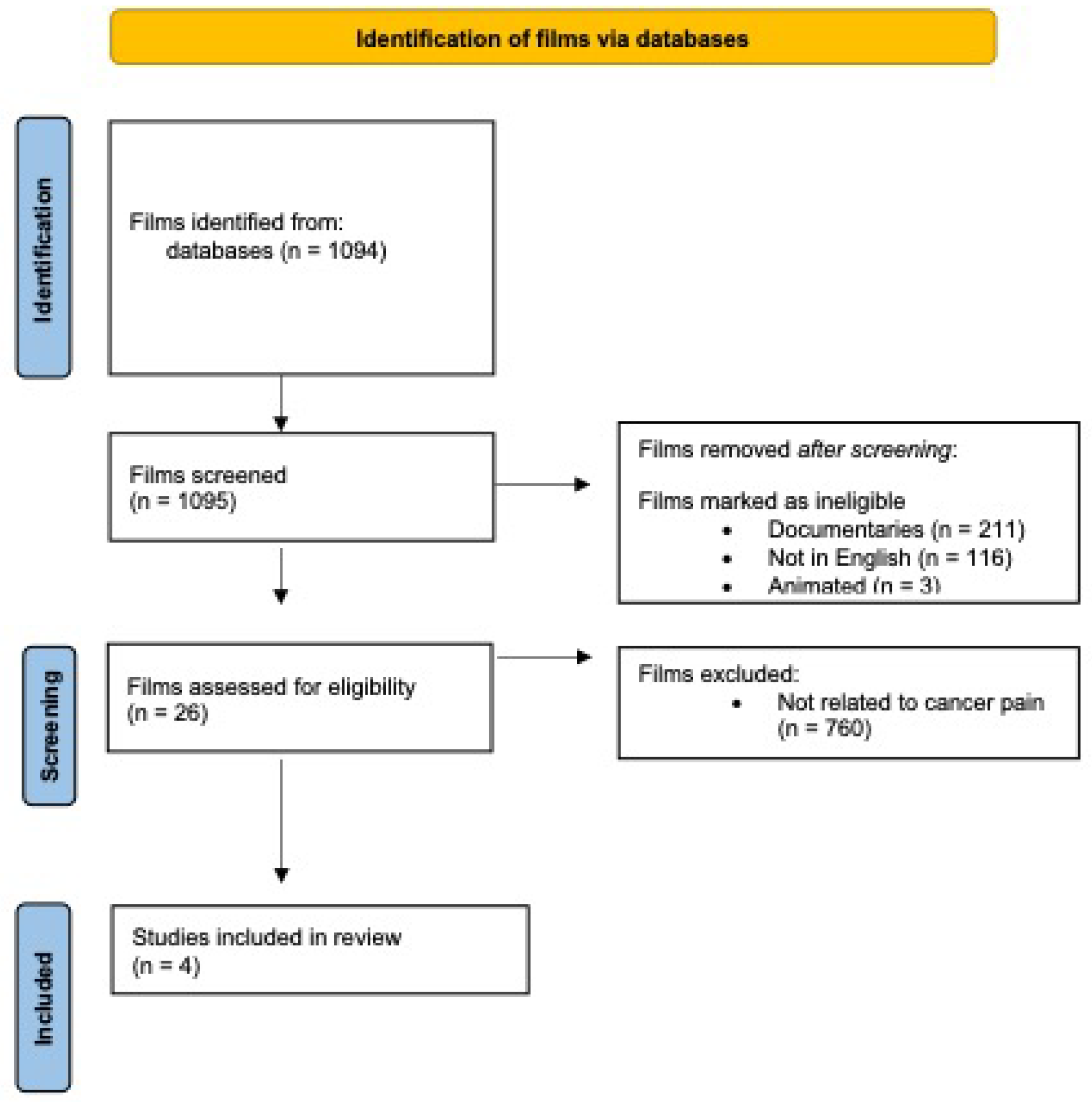

2.2. Screening of Films

2.3. Analysis of Films

3. Results

3.1. Depictions of Characters’ Lives with Pain

3.1.1. Cancer Pain as Adversely Affecting Characters’ Quality of Life

3.1.2. Cancer Pain as Affecting the Lives of Those Close to Characters with Cancer

Does God want us to suffer? What if the answer to that question is yes? See I’m not particularly sure that God wants us to be happy…I suggest to you that it is because God loves us that he makes us the gift of suffering. Or to put it another way, pain is God’s megaphone to rouse a deaf world. You see, we are like blocks of stone out of which the sculptor carves the form of men. The blows of his chisel which hurt us so much are what makes us perfect (11:11).

Yesterday, a friend of mine, a very brave, good woman, collapsed in terrible pain. One minute she was fit and well, next minute she was in agony. She’s now in hospital and this morning I was told she’s suffering from cancer. Why? See, if love someone you don’t want them to suffer. You can’t bear it. You want to take their suffering onto yourself. If even I feel like that, why doesn’t God? (1:10:17).

- Jack: What’s happening to me, Warnie?...I’m so afraid…of thinking that suffering is just suffering after all, no cause, no purpose, no pattern.

- Warnie: I don’t know what to tell you, Jack.

- Jack: Hmm? Nothing. There’s nothing to say. I know that now. I’ve just come up against a bit of experience, Warnie. Experience is a brutal teacher, but you’ll learn. My God, you’ll learn (1:58:33).

- Harry: Only God knows why these things have to happen.

- Jack: God knows but does God care?

- Harry: Of course. We see so little here. We are not the Creator.

- Jack: No, no. We’re the creatures aren’t we, really? We’re the rats in the cosmic laboratory. I have no doubt the experiment is for our own good, but it still makes God the vivisectionist, doesn’t it?

- Harry: Jack…

- Jack: NO! This is blood awfulness and that’s all there is to it (2:00:16).

3.2. Depictions of Healthcare Professionals Looking after Patients with Pain

- Lead physician: Morning.

- Rémy: Good morning!

- Lead physician: It really smells like cigarette smoke in here. You haven’t been smoking I hope?

- Rémy: Oh no never! I light a candle to meditate.

- Lead physician: You aren’t having any IV solutions?

- Rémy: Dr. Lévesque had it removed. (Turns toward and addresses the other two physicians in the room) Good morning, my doctor-esses.

- Lead physician: Take a deep breath. Does it hurt here?

- Rémy: Oh, yes.

- Lead physician: And here, too?

- Rémy: There too, yes.

- Lead physician: Is it unbearable?

- Rémy: Goodness, no!

- Lead physician: You’re in high spirits.

- Rémy: Couldn’t be higher!

- Lead physician: How do you sleep?

- Rémy: Like a baby.

- Lead physician: Then I won’t prescribe painkillers.

- Rémy: Forget it!

- Lead physician: That’s wonderful. I always say, the longer they stay lucid, the better.

- Rémy: I plan to remain lucid til I die.

- Lead physician: Wonderful, Mr. Parenteau.

- Rémy: Thanks so much, Dr. Dubé.

- Lead physician: I’m not Dr. Dubé.

- Rémy: How fitting, because I’m not Mr. Parenteau! (49:49).

- Dr. Kelekian: Dr. Bearing.

- Susie: It’s time for patient-controlled analgesia. The pain is killing her.

- Dr. Kelekian: Dr. Bearing are you in pain?

- Prof. Bearing: I don’t believe this.

- Dr. Kelekian: I want a morphine drip.

- Susie: What about patient-controlled? She could be more alert?

- Dr. Kelekian: Ordinarily, yes. But in her case, no.

- Susie: B-but I think she would really rather…(she looks down and away from Dr. Kelekian, as if embarrassed).

- Dr. Kelekian: She’s earned a rest. Morphine. Ten push now and start at 10 an hour. Dr. Bearing, try to relax. (Susie looks at Dr. Kelekian with a look of incredulousness) (1:13:36).

- Prof. Bearing: I trust this will have a soporific effect.

- Susie: I’m not sure about that but it sure does make you feel sleepy (1:15:43).

- Aurora: Excuse me. It’s after ten, give my daughter the pain shot please.

- Nurse 1: Mrs. Greenway. I was going to.

- Aurora: Oh! Good. Go ahead.

- Nurse 1: Just a few minutes (with her voice raised and open hand up).

- Aurora: Well please! It’s after 10, it’s after 10. I don’t see why she has to have this pain (with raised voice).

- Nurse 2: Ma’am, it’s not my patient.

- Aurora: It’s time for her shot! YOU UNDERSTAND? DO SOMETHING! ALL SHE HAS TO DO IS HOLD OUT UNTIL 10 AND IT’S PASSED 10, SHE IS (gasps) IN PAIN, MY DAUGHTER’S (gasps) IN PAIN, GET HER THE SHOT! DO YOU UNDERSTAND?

- Nurse 1: You are going to have to behave, Mr. Greenway.

- Aurora: GIVE MY DAUGHTER THE SHOT!

3.3. Depictions of Therapies for Pain Management

3.4. Depictions of the Settings for Pain Management

4. Discussion

4.1. Depictions of Characters with Cancer Pain

4.2. Depictions of Healthcare Professionals’ Attitudes

4.3. Depictions of Pain Management Strategies

4.4. Depictions of Pain Management Settings

4.5. Implications for Improving Cancer Pain Education with Cinemeducation

4.6. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bouya, S.; Balouchi, A.; Maleknejad, A.; Koochakzai, M.; AlKhasawneh, E.; Abdollahimohammad, A. Cancer pain management among oncology nurses: Knowledge, attitude, related factors, and clinical recommendations: A systematic review. J. Cancer Ed. 2019, 34, 839–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eyigor, S. Fifth-year medical students’ knowledge of palliative care and their views on the subject. J. Palliat. Med. 2013, 16, 941–946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sloan, P.A.; Donnelly, M.B.; Schwartz, R.W.; Sloan, D.A. Cancer pain assessment and management by housestaff. Pain 1996, 67, 475–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sloan, P.A.; LaFountain, P.; Plymale, M.; Johnson, M.; Snapp, J.; Sloan, D.A. Cancer pain education for medical students: The development of a short course on CD-ROM. Pain Med. 2002, 3, 66–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burge, F.; McIntyre, P.; Kaufman, D.; Cummings, I.; Frager, G.; Pollet, A. Family Medicine residents’ knowledge and attitudes about end-of-life care. J. Palliat. Care 2000, 16, 5–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lasch, K.; Greenhill, A.; Wilkes, G.; Carr, D.; Lee, M.; Blanchard, R. Why study pain? A qualitative analysis of medical and nursing faculty and students’ knowledge of and attitudes to cancer pain management. J. Palliat. Med. 2002, 5, 57–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Von Roenn, J.H.; Cleeland, C.S.; Gonin, R.; Hatfield, A.K.; Pandya, K.J. Physicians’ attitudes and practice in cancer pain management. Ann. Intern. Med. 1993, 119, 121–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheehan, D.K.; Webb, A.; Bower, D.; Einsporn, R. Level of cancer pain knowledge among baccalaureate student nurses. J. Pain Symptom. Manag. 1992, 7, 478–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sand, R.; Blackall, B.; Abrahm, J.L.; Healey, K. A survey of physicians’ education in caring for the dying: Identified training needs. J. Cancer Ed. 1998, 13, 242–247. [Google Scholar]

- Pilowsky, I. An outline curriculum on pain for medical schools. Pain 1988, 33, 1–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, N.; Thomson, D. A comparison of the knowledge of chronic pain and its management in final year physiotherapy and medical students. Eur. J. Pain 2009, 13, 38–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mezei, L.; Murinson, B.B.; Johns Hopkins Pain Curriculum Development Team. Pain education in North American medical schools. J. Pain 2011, 12, 1199–1208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Briggs, E.V.; Carr, E.C.J.; Whittaker, M.S. Survey of undergraduate pain curricula for healthcare professionals in the United Kingdom. Eur. J. Pain 2011, 15, 789–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watt-Watson, J.; Peter, E.; Clark, A.J.; Dewar, A.; Hadjistavropoulos, T.; Morley-Foster, P.; O’Leary, C.; Raman-Wilms, L.; Unruh, A.; Webber, K.; et al. The ethics of Canadian entry-to-practice pain competencies: How are we doing? Pain Res. Manag. 2013, 18, 25–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watt-Watson, J.; McGillion, M.; Hunter, J.; Choiniere, M.; Clark, A.J.; Dewar, A.; Johnston, C.; Lynch, M.; Morley-Foster, P.; Moulin, D.; et al. A survey of pre-licensure pain curricula in health science faculties in Canadian universities. Pain Res. Manag. 2009, 14, 439–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.T.; Fagan, M.J.; Diaz, J.A.; Reinert, S.E. Is treating chronic pain torture? Internal medicine residents’ experience with patients with chronic nonmalignant pain. Teach Learn. Med. 2007, 19, 101–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yanni, L.M.; McKinney-Ketchum, J.L.; Harrington, S.B.; Huynh, C.; Bs, S.A.; Matsuyama, R.; Coyne, P.; Johnson, B.A.; Fagan, M.; Garufi-Clark, L. Preparation, confidence, and attitudes about chronic non-cancer pain in graduate medical education. J. Grad. Med. Educ. 2010, 2, 260–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egnew, T.; Lewis, P.R.; Schaad, D.C.; Karuppiah, S.; Mitchell, S. Medical student perceptions of medical school education about suffering. Fam. Med. 2014, 46, 39–44. [Google Scholar]

- Heavner, J. Teaching pain management to medical students. Pain Pract. 2009, 9, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leila, N.-M.; Pirkko, H.; Eeva, P.; Eija, K.; Reino, P. Training medical students to manage a chronic pain patient: Both knowledge and communication skills are needed. Eur. J. Pain. 2006, 10, 167–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinstein, S.M.; Laux, L.F.; Thornby, J.I.; Lorimor, R.J.; Hill, C.S.; Thorpe, D.M.; Merrill, J.M. Medical students’ attitudes toward pain and the use of opioid analgesics: Implications for changing medical school curriculum. South Med. J. 2000, 93, 472–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corrigan, C.; Desnick, L.; Marshall, S.; Bentov, N.; Rosenblatt, R.A. What can we learn from first-year medical students’ perception of pain in the primary care setting? Pain Med. 2011, 12, 1216–1222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilson, J.F.; Brockopp, G.W.; Kryst, S.; Steger, H.; Witt, W.O. Medical students’ attitudes towards pain before and after a brief course on pain. Pain 1992, 50, 251–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ameringer, S.; Fisher, D.; Sreedhar, S.; Ketchum, J.M.; Yanni, L. Pediatric pain management education in medical students: Impact of a web-based module. J. Palliat. Med. 2012, 15, 978–983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Argyra, E.; Siafaka, I.; Moutzouri, A.; Papadopoulos, V.; Rekatsina, M.; Vadalouca, A.; Theodoraki, K. How does an undergraduate pain course influence future physicians’ awareness of chronic pain concepts? A comparative study. Pain Med. 2015, 16, 301–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strong, J.; Meredith, P.; Darnell, R.; Chong, M.; Roche, P. Does participation in a pain course based on the International Association for the Study of Pain’s curricula guidelines change student knowledge about pain? Pain Res. Manag. 2003, 8, 137–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Carr, D.; Bradshaw, Y. Time to flip the curriculum? Anesthesiology 2014, 120, 12–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murinson, B.B.; Gordin, V.; Flynn, S.; Driver, L.C.; Gallagher, R.M.; Grabois, M.; Medical Student Education Sub-committee of the American Academy of Pain Medicine. Recommendations for a new curriculum in pain medicine for medical students: Toward a career distinguished by competence and compassion. Pain Med. 2013, 14, 345–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, G.; Weiner, D. Essential components of a medical student curriculum on chronic pain management in older adults: Results of a modified Delphi process. Pain Med. 2002, 3, 240–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murinson, B.B.; Nenortas, E.; Mayer, R.S.; Mezei, L.; Kozachik, S.; Nesbit, S.; Haythornthwaite, J.A.; Campbell, J.N. A new program in pain medicine for medical students: Integrating core curriculum knowledge with emotional and reflective development. Pain Med. 2011, 12, 186–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tellier, P.-P.; Bélanger, E.; Rodríguez, C.; Ware, M.A.; Posel, N. Improving undergraduate medical education about pain assessment and management: A qualitative descriptive study of stakeholders’ perceptions. Pain Res. Manag. 2013, 18, 259–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wittert, G.; Nelson, A.J. Medical education: Revolution, devolution and evolution in curriculum philosophy and design. Med. J. Aust. 2009, 191, 35–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Charon, R. Narrative medicine: A model for empathy, reflection, profession, and trust. JAMA 2001, 286, 1897–1902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumagai, A. A conceptual framework for the use of illness narratives in medical education. Acad. Med. 2008, 83, 653–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wear, D. “Face-to-face with it”: Medical students’ narratives about their end-of-life education. Acad. Med. 2008, 77, 271–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gelo, F. The HeART of Empathy: Using the Visual Arts in Medical Education. Available online: https://medhum.med.nyu.edu/view/12975 (accessed on 1 November 2021).

- Alexander, M. The Doctor: A seminal video for cinemeducation. Fam. Med. 2002, 34, 92–94. [Google Scholar]

- Alexander, M.; Hall, M.N.; Pettice, Y.J. Lights, camera, action: Using film to teach the ACGME competencies. Fam. Med. 2007, 39, 20–23. [Google Scholar]

- DiBartolo, M.; Seldomridge, L. Cinemeducation: Teaching end-of-life issues using feature films. J. Gerontol. Nurs. 2009, 35, 30–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozcakir, A.; Bilgel, N. Educating medical students about the personal meaning of terminal illness using the film, “Wit”. J Palliat Med. 2014, 17, 913–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnston, C.; Chan, M. Making film vignettes to teach medical ethics. Med. Ed. 2012, 46, 1099–1136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blasco, P.G.; Moreto, G.; Roncoletta, A.F.T.; Levites, M.R.; Janaudis, M.A. Using movie clips to foster learners’ reflection: Improving education in the affective domain. Fam. Med. 2006, 38, 94–96. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Lumlertgul, N.; Kijpaisalratana, N.; Pityaratstian, N.; Wangsaturaka, D. Cinemeducation: A pilot student project using movies to help students learn medical professionalism. Med. Teach. 2009, 31, e327–e332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akram, A.; O’Brien, A.; O’Neill, A.; Latham, R. Crossing the line–learning psychiatry at the movies. Int. Rev. Psychiatry 2009, 21, 267–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gorring, H.; Loy, J. Cinemeducation: Using film as an educational tool in mental health services. Health Info. Libr. J. 2014, 311, 84–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graf, H.; Abler, B.; Weydt, P.; Kammer, T.; Plener, P.L. Development, implementation, and evaluation of a movie-based curriculum to teach psychpathology. Teach. Learn Med. 2014, 26, 86–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalra, G. Teaching diagnostic approach to a patient through cinema. Epilepsy Behav. 2011, 22, 571–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalra, G.S. Lights, camera and action: Learning necrophilia in a psychiatry movie club. J. Forensic. Leg. Med. 2013, 20, 139–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuhnigk, O.; Schreiner, J.; Reimer, J.; Emami, R.; Naber, D.; Harendza, S. Cinemeducation in psychiatry: A seminar in undergraduate medical education combining a movie, lecture, and patient interview. Acad. Psychiatry 2012, 36, 205–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webster Jr, C.R.; Valentine, L.C.; Gabbard, G.O. Film clubs in psychiatric education: The hidden curriculum. Acad. Psychiatry 2015, 39, 601–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lederer, S.E. Dark Victory: Cancer and popular Hollywood film. B Hist. Med. 2007, 81, 94–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavisic, J.; Chilton, J.; Walter, G.; Soh, N.L.; Martin, A. Childhood cancer in the cinema: How the celluloid mirror reflects psychosocial care. J. Pediatr. Hematol. Oncol. 2014, 36, 430–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Auwen, A.; Emmons, M.; Dehority, W. Portrayal of immunization in American cinema: 1925 to 2016. Clin. Pediatr. 2020, 59, 360–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gallos, L.K.; Potiguar, F.Q.; Andrade Jr., J.S.; Makse, H.A. IMDb network revisited: Unveiling fractal and modular properties from a typical small-world network. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wasserman, M.; Zen, X.H.T.; Amaral, L.A.N. Cross-evaluation of metrics to estimate the significance of creative works. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2015, 112, 1281–1286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yanicak, A.; Mohorn, P.L.; Monterroyo, P.; Furgiuele, G.; Waddington, L.; Bookstaver, P.B. Public perception of pharmacists: Film and television portrayals from 1970 to 2013. J. Am. Pharm. Assoc. 2015, 55, 578–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flores, G. Mad scientists, compassionate healers, and greedy egotists: The portrayal of physicians in the movies. J. Natl. Med. Assoc. 2002, 94, 635–658. [Google Scholar]

- Tenzek, K.E.; Nickels, B.M. End-of-life in Disney and Pixar films: An opportunity for engaging in difficult conversation. OMEGA 2019, 80, 49–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mueri, K.; Kennedy, M.; Pavlova, M.; Jordan, A.; Lund, T.; Neville, A.; Belton, J.; Noel, M. The sociocultural context of pediatric pain: An examination of the portrayal of pain in children’s popular media. Pain 2021, 162, 967–975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harriger, J.A.; Wick, M.R.; Trivedi, H.; Callahan, K.E. Strong hero or violent playboy? Portrayals of masculinity in children’s animated movies. Sex Roles 2021, 85, 677–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, J.; Thorogood, N. ; Qualitative Methods for Health Research; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Gerritsen, D.L.; Kuin, Y.; Nijboer, J. Dementia in the movies: The clinical picture. Aging. Ment. Health 2014, 18, 276–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penn, D.L.; Chamberlin, C.; Mueser, K.T. The effects of a documentary film about schizophrenia on psychiatric stigma. Schizophr. Bull. 2003, 29, 383–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kerby, J.; Calton, T.; Dimambro, B.; Flood, C.; Glazebrook, C. Anti-stigma films and medical students’ attitudes towards mental illness and psychiatry: Randomized controlled trial. Psychiatr. Bull. 2008, 32, 345–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Röhm, A.; Hastall, M.R.; Ritterfeld, U. How movies shape students’ attitudes toward individuals with schizophrenia: An exploration of the relationships between entertainment experience and stigmatization. Issues Ment. Health Nurs. 2017, 38, 193–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hollingshead, N.A.; Meints, S.; Middleton, S.K.; Free, C.A.; Hirsh, A.T. Examining influential factors in providers’ chronic pain treatment decisions: A comparison of physicians and medical students. BMC Med. Educ. 2015, 15, 164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tait, R.C.; Chibnall, J.T. Physician judgements of chronic pain patients. Soc. Sci. Med. 1997, 45, 1199–1205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allegretti, A.; Borkan, J.; Reis, S.; Griffiths, F. Paired interviews of shared experiences around chronic low back pain: Classic mismatch between patients and their doctors. Fam. Pr. 2010, 27, 678–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calpin, P.; Imran, A.; Harmon, D. A comparison of expectations of physicians and patients with chronic pain for pain clinic visits. Pain Pr. 2017, 17, 305–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duke, G.; Haas, B.K.; Yarbrough, S.; Northam, S. Pain management knowledge and attitudes of baccalaureate nursing students and faculty. Pain Manag. Nurs. 2013, 14, 11–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plaisance, L.; Logan, C. Nursing students’ knowledge and attitudes regarding pain. Pain Manag. Nurs. 2006, 7, 167–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Nieker, L.M.; Martin, F. The impact of the nurse-physician professional relationship on nurses’ experience of ethical dilemmas in effective pain management. J. Prof. Nurs. 2002, 18, 276–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Niekerk, L.M.; Martin, F. The impact of the nurse-physician relationship on barriers encountered by nurses during pain management. Pain Manag. Nurs. 2003, 4, 3–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monks, R. Nurses experience feelings of disempowerment when caring for patients in severe pain. Evid. Based Nurs. 2016, 19, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morgan, B.D. Nursing attitudes toward patients with substance use disorders in pain. Pain Manag. Nurs. 2014, 15, 167–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brockopp, D.; Downey, E.; Powers, P.; Vanderveer, B.; Warden, S.; Ryan, P.; Saleh, U. Nurses’ clinical decision making regarding the management of pain. Accid. Emerg. Nurs. 2004, 12, 224–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clabo, L.M.L. An ethnography of pain assessment and the role of social context on two postoperative units. J. Adv. Nurs. 2008, 61, 531–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fagerhaugh, S.Y.; Strauss, A. Politics of Pain Management: Staff Patient Interaction; Addison-Wesley: Menlo Park, CA, USA, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Aitini, E.; Bordi, P.; Dell’Agnola, C.; Fontana, E.; Liguigli, W.; Quaini, F. Narrative literature and cancer: Improving the doctor-patient relationship. Tumori 2012, 98, e152–e154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanchard, C.G.; Ruckdeschel, J.C. Psychosocial aspects of cancer in adults: Implications for teaching medical students. J. Cancer Ed. 1986, 1, 237–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mastroianni, C.; Marchetti, A.; D’Angelo, D.; Artico, M.; Giannarelli, D.; Magna, E.; Motta, P.C.; Piredda, M.; Casale, G. De Marinis, M.G. Italian nursing students’ attitudes towards care of the dying patient: A multi-center descriptive study. Nurs. Educ. Today 2021, 104, 104991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.-M.; Ahn, D.-S. Medical-themed film and literature course for premedical students. Med. Teach. 2004, 26, 534–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorenz, K.A.; Steckart, M.J.; Rosenfeld, K.E. End-of-life education using the dramatic arts: The Wit educational initiative. Acad. Med. 2004, 79, 481–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Film | Year of Release | Box Office Earnings | Selected Awards Won |

|---|---|---|---|

| Terms of Endearment | 1983 | $108,423,749 | Academy Awards: |

| Best Picture, Best Director, Best Adapted | |||

| Screenplay, Best Actress, Best Supporting Actor | |||

| Golden Globe Awards: | |||

| Best Motion Picture—Drama, | |||

| Best Actress in a Motion Picture—Drama, | |||

| Best Supporting Actor—Motion Picture, | |||

| Best Screenplay—Motion Picture | |||

| Shadowlands | 1993 | $25,842,377 | Academy Awards: |

| Nomination for Best Actress, | |||

| Nomination for Best Adapted Screenplay | |||

| Wit | 2001 | not applicable | Golden Globes: |

| Best Mini-series or Motion Picture Made for | |||

| Television, Best Performance by an Actress in a | |||

| Mini-Series or Motion Picture Made for | |||

| Television | |||

| Primetime Emmy Award: | |||

| Outstanding Made for Television Movie, | |||

| Outstanding Directing for a Miniseries, Movie | |||

| or a Special, Outstanding Lead Actress, | |||

| Outstanding Support Actress, Outstanding | |||

| Writing for a Miniseries, Movie or Dramatic | |||

| Special | |||

| The Barbarian Invasions | 2003 | $34,883,010 | Academy Awards: |

| Best Foreign Language Film, | |||

| Nomination for Best Original Screenplay | |||

| Golden Globes: | |||

| Nomination for Best Foreign Language Film |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mukhida, K.; Sedighi, S.; Hart, C. “Give My Daughter the Shot!”: A Content Analysis of the Depiction of Patients with Cancer Pain and Their Management in Hollywood Films. Curr. Oncol. 2022, 29, 8207-8221. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol29110648

Mukhida K, Sedighi S, Hart C. “Give My Daughter the Shot!”: A Content Analysis of the Depiction of Patients with Cancer Pain and Their Management in Hollywood Films. Current Oncology. 2022; 29(11):8207-8221. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol29110648

Chicago/Turabian StyleMukhida, Karim, Sina Sedighi, and Catherine Hart. 2022. "“Give My Daughter the Shot!”: A Content Analysis of the Depiction of Patients with Cancer Pain and Their Management in Hollywood Films" Current Oncology 29, no. 11: 8207-8221. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol29110648

APA StyleMukhida, K., Sedighi, S., & Hart, C. (2022). “Give My Daughter the Shot!”: A Content Analysis of the Depiction of Patients with Cancer Pain and Their Management in Hollywood Films. Current Oncology, 29(11), 8207-8221. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol29110648