Delivery of Virtual Care in Oncology: Province-Wide Interprofessional Consensus Statements Using a Modified Delphi Process

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Modified Delphi

2.2. Literature Review

2.3. Steering Committee

2.4. Consensus Process

3. Results

3.1. Consensus Group

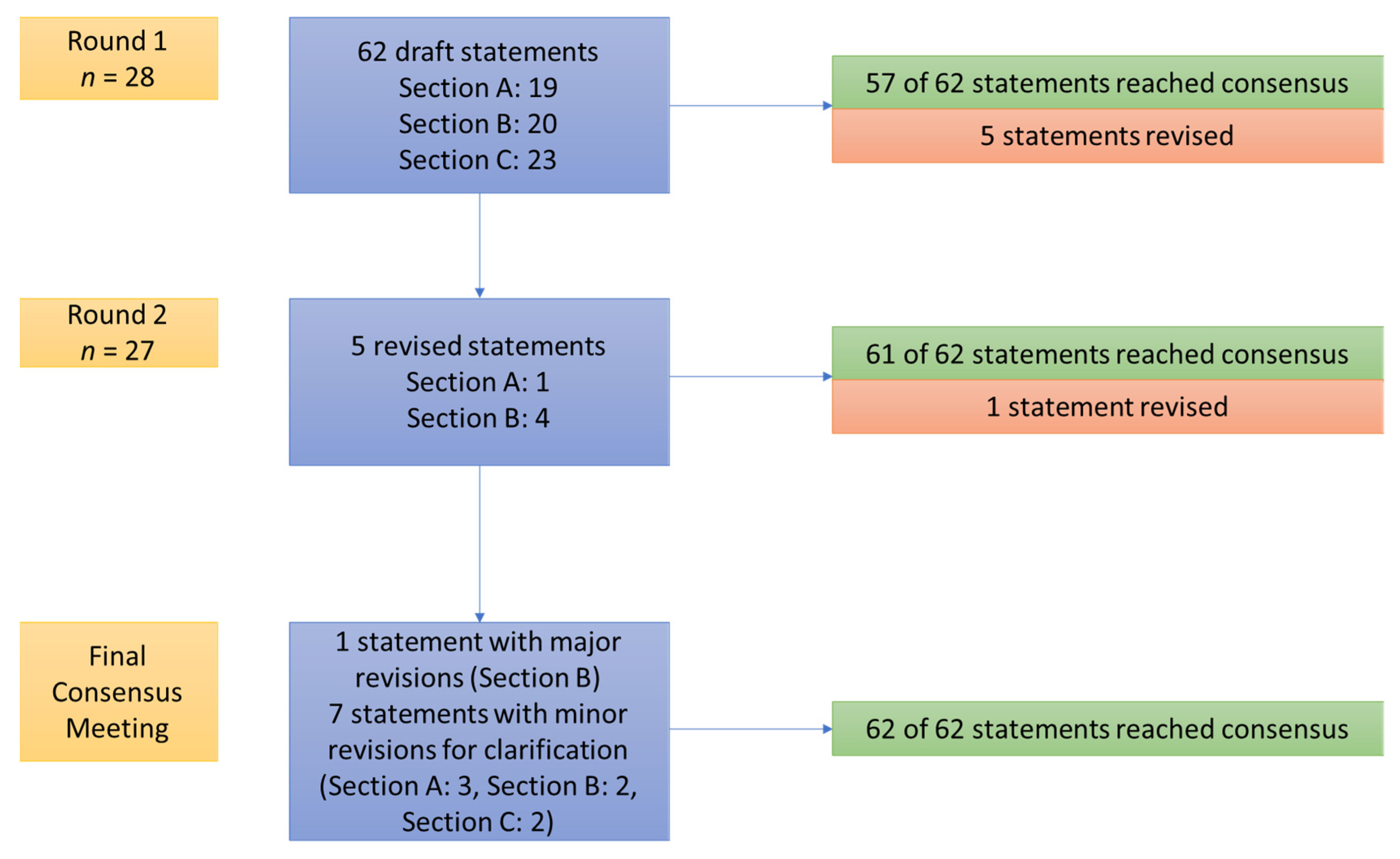

3.2. Consensus Process

3.3. Section A—Demographics, Logistics, and Implementation

3.4. Section B—Diagnosis and Prognosis

3.5. Section C—Clinical Characteristics, Active Management, and Follow-Up

3.6. Qualitative Feedback

4. Discussion

Strengths and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Questions Used by the Steering Committee to Draft Consensus Statements

- Section A: Demographics, Logistics, and Implementation

- What are non-clinical patient characteristics that are best suited for virtual care?

- What environmental and equipment requirements are needed for virtual cancer care?

- How can virtual cancer care be implemented in multidisciplinary care?

- Does having access to local health care resources influence suitability for virtual care? What type of resources?

- Section B: Diagnosis and Prognosis

- What are steps to facilitate safe and accurate diagnosis of cancer via virtual care?

- How can you best communicate a diagnosis, investigations (e.g., results of staging, blood tests) and prognosis virtually? Should diagnosis of cancer ever be made virtually?

- In what scenarios should a diagnosis or prognosis not be communicated virtually?

- Section C: Clinical characteristics, active management, and follow-up

- What are the general recommendations that apply to the management of patients with cancer using virtual care?

- Are there particular clinical characteristics that are more conducive to virtual care?

- Which components of cancer-related surgery are suitable for virtual care?

- Which components of radiotherapy are suitable for virtual care?

- Which systemic treatment regimens can be managed using virtual care?

- What are cancer survivorship considerations during virtual care?

- What are rural and remote oncology considerations for virtual care?

References

- Meti, N.; Rossos, P.G.; Cheung, M.C.; Singh, S. Virtual Cancer Care During and Beyond the COVID-19 Pandemic: We Need to Get It Right. JCO Oncol. Pract. 2020, 16, 527–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, W.; Guan, W.; Chen, R.; Wang, W.; Li, J.; Xu, K.; Li, C.; Ai, Q.; Lu, W.; Liang, H.; et al. Cancer patients in SARS-CoV-2 infection: A nationwide analysis in China. Lancet Oncol. 2020, 21, 335–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Ouyang, W.; Chua, M.L.K.; Xie, C. SARS-CoV-2 Transmission in Patients With Cancer at a Tertiary Care Hospital in Wuhan, China. JAMA Oncol. 2020, 6, 1108–1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Zhang, H.; Han, H.; He, T.; Labbe, K.E.; Hernandez, A.V.; Chen, H.; Velcheti, V.; Stebbing, J.; Wong, K.-K. Clinical Characteristics and Outcomes of COVID-19–Infected Cancer Patients: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. JNCI J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2020, 113, 371–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribas, A.; Sengupta, R.; Locke, T.; Zaidi, S.K.; Campbell, K.M.; Carethers, J.M.; Jaffee, E.M.; Wherry, E.J.; Soria, J.-C.; D’Souza, G. Priority COVID-19 Vaccination for Patients with Cancer while Vaccine Supply Is Limited. Cancer Discov. 2021, 11, 233–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H.; Zhang, L. Risk of COVID-19 for patients with cancer. Lancet Oncol. 2020, 21, e180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agha, M.; Blake, M.; Chilleo, C.; Wells, A.; Haidar, G. Suboptimal Response to Coronavirus Disease 2019 Messenger RNA Vaccines in Patients With Hematologic Malignancies: A Need for Vigilance in the Postmasking Era. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2021, 8, ofab353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, T.H. Creating the New Normal: The Clinician Response to Covid-19. Available online: https://catalyst.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/CAT.20.0076 (accessed on 20 March 2020).

- ASCO. Available online: https://www.asco.org/asco-coronavirus-information (accessed on 5 April 2021).

- NCCN. Available online: https://www.nccn.org/about/news/newsinfo.aspx?NewsID=1949 (accessed on 5 April 2021).

- ESMO. Available online: https://www.esmo.org/newsroom/covid-19-and-cancer (accessed on 5 April 2021).

- Hazin, R.; Qaddoumi, I. Teleoncology: Current and future applications for improving cancer care globally. Lancet Oncol 2010, 11, 204–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Berlin, A.; Lovas, M.; Truong, T.; Melwani, S.; Liu, J.; Liu, Z.A.; Badzynski, A.; Carpenter, M.B.; Virtanen, C.; Morley, L.; et al. Implementation and Outcomes of Virtual Care Across a Tertiary Cancer Center During COVID-19. JAMA Oncol. 2021, 7, 597–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, R.; Sundaresan, T.; Reed, M.E.; Trosman, J.R.; Weldon, C.B.; Kolevska, T. Telehealth in Oncology During the COVID-19 Outbreak: Bringing the House Call Back Virtually. JCO Oncol. Pract. 2020, 16, 289–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segelov, E.; Underhill, C.; Prenen, H.; Karapetis, C.; Jackson, C.; Nott, L.; Clay, T.; Pavlakis, N.; Sabesan, S.; Heywood, E.; et al. Practical Considerations for Treating Patients With Cancer in the COVID-19 Pandemic. JCO Oncol. Pract. 2020, 16, 467–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sirintrapun, S.J.; Lopez, A.M. Telemedicine in Cancer Care. Am. Soc. Clin. Oncol. Educ. Book 2018, 38, 540–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doolittle, G.C.; Allen, A. Practising oncology via telemedicine. J. Telemed. Telecare 1997, 3, 63–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, M.; Khoo, K.; Saltman, D.; Bouttell, E.; Porter, M. The use of telemedicine to care for cancer patients at remote sites. J. Clin. Oncol. 2007, 25, 6538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palkhivala, A. Canada develops models of teleoncology. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2011, 103, 1566–1568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sabesan, S.; Simcox, K.; Marr, I. Medical oncology clinics through videoconferencing: An acceptable telehealth model for rural patients and health workers. Intern. Med. J. 2012, 42, 780–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, B.A.; Larkins, S.L.; Evans, R.; Watt, K.; Sabesan, S. Do teleoncology models of care enable safe delivery of chemotherapy in rural towns? Med. J. Aust. 2015, 203, 406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jhaveri, D.; Larkins, S.; Sabesan, S. Telestroke, tele-oncology and teledialysis: A systematic review to analyse the outcomes of active therapies delivered with telemedicine support. J. Telemed. Telecare 2015, 21, 181–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, S.; Fletcher, G.G.; Yao, X.; Sussman, J. Virtual Care in Patients with Cancer: A Systematic Review. Curr. Oncol. 2021, 28, 3488–3506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loree, J.M.; Dau, H.; Rebić, N.; Howren, A.; Gastonguay, L.; McTaggart-Cowan, H.; Gill, S.; Raghav, K.; De Vera, M.A. Virtual Oncology Appointments during the Initial Wave of the COVID-19 Pandemic: An International Survey of Patient Perspectives. Curr. Oncol. 2021, 28, 671–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loblaw, D.A.; Prestrud, A.A.; Somerfield, M.R.; Oliver, T.K.; Brouwers, M.C.; Nam, R.K.; Lyman, G.H.; Basch, E. American Society of Clinical Oncology Clinical Practice Guidelines: Formal systematic review-based consensus methodology. J. Clin. Oncol. 2012, 30, 3136–3140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ontario Health (Cancer Care Ontario). Ontario Cancer Statistics 2020; Ontario Health (Cancer Care Ontario): Toronto, ON, Canada, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Sabesan, S.; Allen, D.; Loh, P.K.; Caldwell, P.; Mozer, R.; Komesaroff, P.A.; Talman, P.; Williams, M.; Shaheen, N.; Royal Australasian College of Physicians Telehealth Working Group. Practical aspects of telehealth: Are my patients suited to telehealth? Intern. Med. J. 2013, 43, 581–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saraswathula, A.; Lee, J.Y.; Megwalu, U.C. Patient preferences regarding the communication of biopsy results in the general otolaryngology clinic. Am. J. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Med. Surg. 2019, 40, 83–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabesan, S.; Allen, D.; Caldwell, P.; Loh, P.K.; Mozer, R.; Komesaroff, P.A.; Talman, P.; Williams, M.; Shaheen, N.; Grabinski, O. Practical aspects of telehealth: Doctor-patient relationship and communication. Intern. Med. J. 2014, 44, 101–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Curigliano, G.; Banerjee, S.; Cervantes, A.; Garassino, M.C.; Garrido, P.; Girard, N.; Haanen, J.; Jordan, K.; Lordick, F.; Machiels, J.P.; et al. Managing cancer patients during the COVID-19 pandemic: An ESMO multidisciplinary expert consensus. Ann. Oncol. 2020, 31, 1320–1335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jazieh, A.R.; Chan, S.L.; Curigliano, G.; Dickson, N.; Eaton, V.; Garcia-Foncillas, J.; Gilmore, T.; Horn, L.; Kerr, D.J.; Lee, J.; et al. Delivering Cancer Care During the COVID-19 Pandemic: Recommendations and Lessons Learned From ASCO Global Webinars. JCO Glob. Oncol. 2020, 6, 1461–1471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boulkedid, R.; Abdoul, H.; Loustau, M.; Sibony, O.; Alberti, C. Using and Reporting the Delphi Method for Selecting Healthcare Quality Indicators: A Systematic Review. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e20476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Consensus Statement | Agreement | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Round 1 (n = 28) | Round 2 (n = 27) * | Consensus Meeting * | |

| Demographics and Implementation | |||

| A1a. All patients should be considered and, if clinically feasible, offered the option of virtual cancer care regardless of demographics (e.g., gender, race/ethnicity, language spoken, income, education, rurality, physical and/or mental disabilities, indigenous identity). Special effort should be made towards patients without good access to technology, or those who are uncomfortable with using technology. | 89% | - | - |

| A1b. It is recommended that resources be created and disseminated to all health care providers and patients to overcome barriers to virtual cancer care. These can include written, video, and/or verbal guidance provided by a member of the oncology team (e.g., clinical administrator) in advance of the virtual visit or point of care resources. | 96% | - | - |

| A1c. Efforts should be made to ensure that virtual cancer care systems are made as easily accessible as possible. For example, health care providers and/or patients who may not have easy access to computer/internet platforms should be provided the option for a telephone visit instead, where appropriate. | 96% | - | - |

| A1d. One suboptimal or unsuccessful technology encounter does not exclude a patient from future technology encounters as long both patient and provider deem clinically and logistically feasible. | 89% | - | - |

| A1e. Caregivers are encouraged to attend virtual visits, especially for patients with language barriers, self-reported lack of comfort with teleoncology, hearing impairment, or cognitive impairment, it may be helpful to organize a family member to be on the teleoncology encounter at the same time. Health care providers should ensure patient privacy and consent is obtained to discuss details of their care with additional persons. | 96% | - | - |

| A1f. A pre-determined and dedicated time period should be allocated for virtual visits. Both health care providers and patients should ensure an environment that is distraction free and provides confidentiality. | 96% | - | - |

| A1g. Adequate time for health care providers prior to and following a virtual care visit should be planned as additional steps (e.g., electronic requests for outside labs, imaging, prescriptions) may increase the amount of time required per visit. | 93% | - | - |

| Equipment and Environment | |||

| A2a. Health care providers should have access to reliable internet connection and an electronic device (e.g., computer, tablet, or smartphone) if using video technology for virtual care. | 100% | - | - |

| A2b. Back-up systems, such as telephone (landline or cellular), should be available during virtual care visits, should technical difficulties arise. Landline telephone is preferred for call quality/stability, if available. If not, then cellular/mobile phone can be used. | 96% | - | - |

| A2c. All visits should be documented using the same standards as in-person assessment. | 96% | - | - |

| A2d. Documentation should state that the visit was carried out virtually and that the patient has consented to a virtual assessment, understanding the limitations of virtual visits, including lack of physical examination. | 96% | - | - |

| A2e. Electronic medical record systems that allow health care providers to access system-wide investigations (including biochemical, radiological, pathological data—that may have been completed outside the institution) and relevant documentation are critical to facilitate virtual visits with patients. | 93% | - | - |

| A2f. To optimize the delivery of virtual cancer care, health care providers and patients should have access to training options (e.g., teleoncology modules and programs). This training should be supported and disseminated by institutions, provincial entities, and/or in collaboration with other virtual cancer care stakeholders (e.g., Ontario Telehealth Network). | 39% | 78% | 100% |

| A2g. If video-based technologies are not available and/or if telephone communication is preferred by health care providers and/or patients, then telephone communication may be reasonable. | 89% | - | 83% (n = 18) |

| Collaborative and Interdisciplinary Care | |||

| A3a. Multidisciplinary tumour boards and case conferences involving medical oncologists, surgeons, radiation oncologists, general practitioners, radiologists, pathologists, nursing, pharmacists, and allied health professionals are feasible and should remain standard of care for discussing cancer patients. Confidential and secure platforms should be chosen to host conferences and discussions as per standards. | 93% | - | - |

| A3b. Involvement of local health care providers in teleoncology encounters should be supported, if possible and available. Administrative support may be required. | 93% | - | - |

| Local Health Care Resources | |||

| A4a. If a care plan is initiated via virtual platforms, a health care provider must be available at the treatment centre to guide and support treatments (e.g., chemotherapy and infusion reactions). | 82% | ||

| A4b. Delivery of virtual cancer care should include efforts to link patients with local laboratory (i.e., blood test) and/or imaging services when appropriate. However, test results should be available to the health care provider and comparable to previous investigations (e.g., comparing imaging scans at follow up visits). If not available, then testing should be carried out at the health care provider’s institution. In order to ensure this is completed in an efficient manner, administrator support is encouraged. | 75% | - | 100% (n = 18) |

| A4c. Access to primary care and emergent care must be included in the discussion of risks and benefits of virtually managed cancer care. Patients receiving virtual cancer care should be counselled on possible risks specific to their care (e.g., chemotherapy toxicity, lymphedema, post-surgical complications) and cancer (e.g., visceral crisis) and appropriate avenues to reach care. Therefore, we encourage that the patient’s local health care provider is made aware of ongoing cancer care and that patients are aware of local resources in the event of complications. | 93% | - | - |

| Consensus Statements | Agreement | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Round 1 (n = 28) | Round 2 (n = 27) * | Consensus Meeting * | |

| Preparation | |||

| B1a. Prior to and during virtual cancer care visits (especially initial consultation), health care teams are encouraged to assess the patient’s ability to understand, process and follow up on the communication of health information delivered virtually (digital and/or over the telephone). | 61% | 81% | 100% (n = 18) |

| B1b. When clinically appropriate, patient preferences regarding method of communication (phone, videoconference, in person) to hear diagnostic and prognostic information should be understood by the health care provider before diagnosis/prognosis is conveyed. Moreover, effort should be made to have a caregiver present, depending on patient preference. | 100% | - | - |

| B1c. When there is uncertainty about definitive diagnosis and/or prognosis, collaborating amongst health care providers/disciplines should occur prior to telecommunication with the patient such that a clear plan of care can be shared virtually. | 82% | - | - |

| B1d. If after collaboration uncertainty is still present, a clear plan should be constructed to communicate to the patient how this uncertainty will be clarified. This plan can be communicated virtually to the patient by one or more health care providers involved. | 82% | - | - |

| Communication | |||

| B2a. The discussion of initial cancer diagnosis and prognosis may occur over virtual care platforms, if that would meet the needs of the patient (e.g., more timely discussions, better family support or patient inability to travel). In addition to in-person standards of communication (e.g., ensuring caregiver and/or supports are available), key elements of an effective virtual interaction regarding cancer diagnosis include (but are not limited to): | 57% | 67% | 91% (n = 22) |

| B2b. Use of video over telephone, if available | 79% | - | - |

| B2c. Placement of camera should be at eye level so that the health care provider does not appear above the patient. | 75% | - | - |

| B2d. Explain at the outset that the conversation is about diagnosis and next steps. | 86% | - | - |

| B2e. Introduce all health care providers present and ask for an introduction of all family/friends that are part of the virtual conversation. | 100% | - | - |

| B2f. If using video-based platforms (that allow sharing digital information on the screen) to conduct a virtual visit, virtual aids that complement the discussion (e.g., imaging, pathology reports, prediction tool outputs) can be shared with the patient, depending on patient preference and feasibility. | 71% | 100% | - |

| B2g. Allow for pauses for question asking and answering. | 96% | - | - |

| B2h. Confirm understanding using the teach back method (i.e., ask patient to explain plan back to the health care provider). | 93% | - | - |

| Communication of Treatment Plans | |||

| B2i. Plan for the interaction and have information on hand that you anticipate patients may ask (e.g., avenues for treatment access, potential start dates, treatment delivery site). | 100% | - | - |

| B2j. Discuss and execute referrals to other services dependent on patient need and treatment plan, e.g., social work, nursing, pharmacy, drug reimbursement or dietician. | 100% | - | - |

| B2k. Include prognosis information as part of the discussion in accordance with patient preference. | 100% | - | - |

| B2l. All interactions about diagnosis and prognosis should be supplemented with educational material (e.g., drug information sheets, disease information, written care plan), and an avenue (e.g., incoming phone line, patient portal, follow up appointment, email) should be provided for questions after review of information and literature. | 86% | - | 94% (n = 18) |

| New diagnoses and prognoses with anticipated limited life expectancies | |||

| B3a. The health care provider should exercise discretion as to whether to convey a metastatic/palliative diagnosis virtually or in-person. The provider should consider the nature of the patient/provider relationship, the expected response to the metastatic/palliative diagnosis, as well as the level of support available to the patient. Exceptions to this statement may include: | 61% | 96% | - |

| B3b. Situations where there is urgency to initiate treatment and virtual care facilitates expediency. | 86% | - | - |

| B3c. The patient has a high symptom burden where they cannot physically attend appointment. | 96% | - | - |

| B3d. A virtual interaction enables a local health care provider to be part of the interaction, where they will be key in co-managing patients and treatment moving forward. | 79% | - | - |

| Consensus Statements | Agreement | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Round 1 (n = 28) | Round 2 (n = 27) * | Consensus Meeting * | |

| General Clinical Considerations | |||

| C1a. If physical examinations and/or investigations (e.g., bloodwork, imaging, pathology) essential for diagnosis/prognosis, symptom management, and/or choice of treatment could not be obtained through a virtual consult, an in-person face-to-face consult is required. | 100% | - | - |

| C1b. Appropriateness of engaging individual patients in virtual care visits for active management depends on the health care provider, as well as patient preference when clinically appropriate. | 89% | - | - |

| C1c. Both curative and non-curative intent virtual management of patients with cancer is appropriate, unless in-person assessment is required by either the health care provider or the patient. | 93% | - | 88% (n = 17) |

| C1d. When available (depending on treatment centre infrastructure), allied health care (e.g., nursing, pharmacy, social work) support should be offered to ensure optimal patient care. | 96% | - | - |

| C1e. General practitioners who actively follow your patients with cancer should be engaged in the virtual discussions, if possible and appropriate, in order to facilitate optimal longitudinal patient care. | 75% | - | - |

| C1f. Health care providers using virtual assessment tools should ensure patients are assessed at the same frequency of visits as in-person assessments. | 82% | - | - |

| C1g. Patients assessed virtually should still be referred for clinical trial eligibility where appropriate. | 100% | - | - |

| C1h. Virtual care could be used for cancer prevention, symptom and pain management, and the assessment of nutrition, drug toxicity, and psychosocial factors (e.g., psychological counselling, activities of daily living, etc.). | 100% | - | - |

| C1i. Virtual follow-up visits that require discussion about recurrent or progressive disease and/or change of treatment due to treatment failure should prompt the health care provider to request that the patient be accompanied on the telephone or video conference by a caregiver. | 75% | - | - |

| Surgical Oncology | |||

| C2a. First consultations with potential surgical cancer patients should be held in-person if there is a requirement for formal physical examination of relevant organ system or other in-person investigations. Otherwise, virtual consult is appropriate. | 96% | ||

| C2b. Surgical planning and post-operative follow up of patients with cancer could be conducted virtually, either when no additional physical examinations or investigations (e.g., bloodwork, imaging, pathology) are needed, or when these examinations and investigations could be completed locally for patients living in remote areas. In the latter case, such consultations are only appropriate if the surgeon is comfortable with the extent of physical examinations performed by local health care providers and their experiences and skills. | 100% | - | - |

| C2c. Post-surgical patients can be assessed virtually unless the need for wound assessment and/or physical examination is required to provide optimal care. If virtual care is performed, we recommend engaging in homecare to patients with active wound issues (i.e., wound care). | 82% | - | - |

| Radiation Therapy | |||

| C3a. First consultations with potential radiation oncology cancer patients should be held in person if formal physical examination of relevant organ system is necessary. Otherwise, virtual care is appropriate. | 86% | - | - |

| C3b. Patients on surveillance or observation following definitive radiation therapy with curative intent can be followed virtually, unless symptoms arise on review of systems that trigger an in-person assessment. Engagement of allied health and family health care providers is recommended. | 93% | - | - |

| C3c. Discussion of radiation treatments can be conducted virtually, as long as there is no requirement for an in-person assessment. | 96% | - | - |

| Medical Therapy | |||

| C4a. First consultations with potential medical and hematology oncology cancer patients should be held in-person for formal physical examination of relevant organ systems and/or any pre-treatment procedures, if necessary. If not, then virtual assessment is appropriate. | 86% | - | - |

| C4b. Patients with cancer receiving active systemic anti-cancer therapy (intravenous and/or oral) can be followed virtually. However, if assessment of tumor lesion is necessary (e.g., neoadjuvant breast cancer treatment), an in-person visit should be facilitated. | 86% | - | - |

| C4c. Patients on surveillance/observation following definitive systemic therapy with curative intent can be followed virtually, unless symptoms arise on review of systems that trigger an in-person assessment. Engagement of locally accessible health care providers is recommended to arrange in-person physical examinations if indicated. | 86% | - | - |

| C4d. Decisions to continue or discontinue systemic treatments that have been previously initiated could be made virtually, if deemed appropriate by health care provider and patient. | 75% | - | 100% (n = 17) |

| Survivorship | |||

| C5a. Cancer survivors under surveillance following curative intent treatment can be safely followed using virtual platforms unless physical examination is indicated and/or required. | 100% | - | - |

| C5b. Virtual inclusion and engagement with family medicine providers can be considered to optimize surveillance. | 86% | - | - |

| C5c. Primary care providers and cancer survivors should be formally notified, in a survivorship care plan or similar document, of the transition to virtual survivorship care. | 89% | - | - |

| Remote and Rural Communities | |||

| C6a. Virtual care could be used for urgent consultation for distant patients who are either unable to visit a specialist in a timely manner or the severity of their symptoms prevent them from travelling long distances. Such visits could be accompanied by the attendance of local healthcare professionals (e.g., nurses, GPs, etc.). | 96% | - | - |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cheung, M.C.; Franco, B.B.; Meti, N.; Thawer, A.; Tahmasebi, H.; Shankar, A.; Loblaw, A.; Wright, F.C.; Fox, C.; Peek, N.; et al. Delivery of Virtual Care in Oncology: Province-Wide Interprofessional Consensus Statements Using a Modified Delphi Process. Curr. Oncol. 2021, 28, 5332-5345. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol28060445

Cheung MC, Franco BB, Meti N, Thawer A, Tahmasebi H, Shankar A, Loblaw A, Wright FC, Fox C, Peek N, et al. Delivery of Virtual Care in Oncology: Province-Wide Interprofessional Consensus Statements Using a Modified Delphi Process. Current Oncology. 2021; 28(6):5332-5345. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol28060445

Chicago/Turabian StyleCheung, Matthew C., Bryan B. Franco, Nicholas Meti, Alia Thawer, Houman Tahmasebi, Adithya Shankar, Andrew Loblaw, Frances C. Wright, Colleen Fox, Naomi Peek, and et al. 2021. "Delivery of Virtual Care in Oncology: Province-Wide Interprofessional Consensus Statements Using a Modified Delphi Process" Current Oncology 28, no. 6: 5332-5345. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol28060445

APA StyleCheung, M. C., Franco, B. B., Meti, N., Thawer, A., Tahmasebi, H., Shankar, A., Loblaw, A., Wright, F. C., Fox, C., Peek, N., Sim, V., & Singh, S., on behalf of the Ontario Health (Cancer Care Ontario) Virtual Care Consensus Group. (2021). Delivery of Virtual Care in Oncology: Province-Wide Interprofessional Consensus Statements Using a Modified Delphi Process. Current Oncology, 28(6), 5332-5345. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol28060445