Both “Vitamin L for Life” and “One Milligram of Satan”: A Multi-Perspective Qualitative Exploration of Adjuvant Endocrine Therapy Use after Breast Cancer

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Recruitment Process

2.3. Data Collection

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Women Who Persisted

3.1.1. Side Effects

“I knew there was going to be side effects, because everybody kept saying that. And I think it was a frame of mind I put myself in that I was going to power through it.”(Participant, age 51)

“I think it could come down to almost, like, you need to be prescribed exercise.”(Participant, age 60)

“Being able to talk to other people about what worked and what didn’t, the whole question of, what can I expect? For instance, with bone pain, a lot of people talk about how Claritin, which is an anti-allergy pill, apparently is magical for bone pain, and so I haven’t used it, but it’s good to know.”(Participant, age 51)

3.1.2. Rationale for Use

“The bigger piece for me was, what would it cost me if I abandon it and [the cancer] was to come back? Would I at least feel comfort that I did everything, or would I be plagued or haunted by, I abandoned early because I was uncomfortable?”(Participant, age 41)

3.1.3. Experiences with the Healthcare System

“I wouldn’t have stayed on it probably if it wasn’t for [my oncologist]. I just really respect his knowledge and he was just so caring and thoughtful and sensitive; and had a little bit of a humor spin to things. He was amazing and I could really tell him anything.”(Participant, age 60)

“If I had to go to the hospital to get [AET], I’m not sure I would because that parking is ridiculous.”(Participant, age 66)

“I don’t go to groups, because–I’m not depressed. I have a feeling [laughing] if I went to those groups, maybe I would get depressed.”(Participant, age 70)

3.2. Women Who Discontinued

3.2.1. Overwhelming Side Effects

“I’m going between oncology and my family doctor saying, “What’s wrong with me, I don’t feel good”–and then starting the fear of, “It must be in my bones, my bones hurt, the cancer must be back”. So I kind of went into a tailspin.”(Participant, age 58)

3.2.2. Reluctance

“I wasn’t quite sure how the hormone blocker worked. I didn’t quite understand that I would be having decreased estrogen and then all the bad stuff that goes with that.”(Participant, age 58)

“I guess it was a matter of which are you more afraid of, recurrence of the cancer or osteoporosis? And I guess I picked osteoporosis.”(Participant, age 73)

3.2.3. Experiences with Healthcare Providers

“And by her saying, “That’s it, enough, no more”, I kind of felt relieved. I’m scared, but I’m relieved and I just came to terms with it.”(Participant, age 58)

3.2.4. Contextual Factors

“It would also be different if the stage of my cancer was different. But being a stage one, I felt that the odds were in my favour.”(Participant, age 67)

3.3. Healthcare Providers

3.3.1. Barriers at Patient- and System-Levels

“There is a lot of misinformation out there. And that can be either through the internet or through a relationship with somebody that they know who had a bad outcome with one of the drugs. So they’ll get a very skewed view on what the medication’s all about, or the potential harms.”(Oncologist)

3.3.2. Side Effect Management

“I would hope that if there were going to be an effort made to improve adherence to medication taken over the long-term, that it could be envisioned as something broader than that. That it did also include advice on healthy living which I think may provide numerically as much benefit as the hormone treatments and maybe more.”(Oncologist)

3.3.3. Patient–Provider Interactions

“It’s not a one size fits all. It’s a communication and consultation process with each individual patient, depending on their disease characteristics, goals, beliefs, comorbidities, age. It’s not something you can predict before you’re meeting with that individual.”(Oncologist)

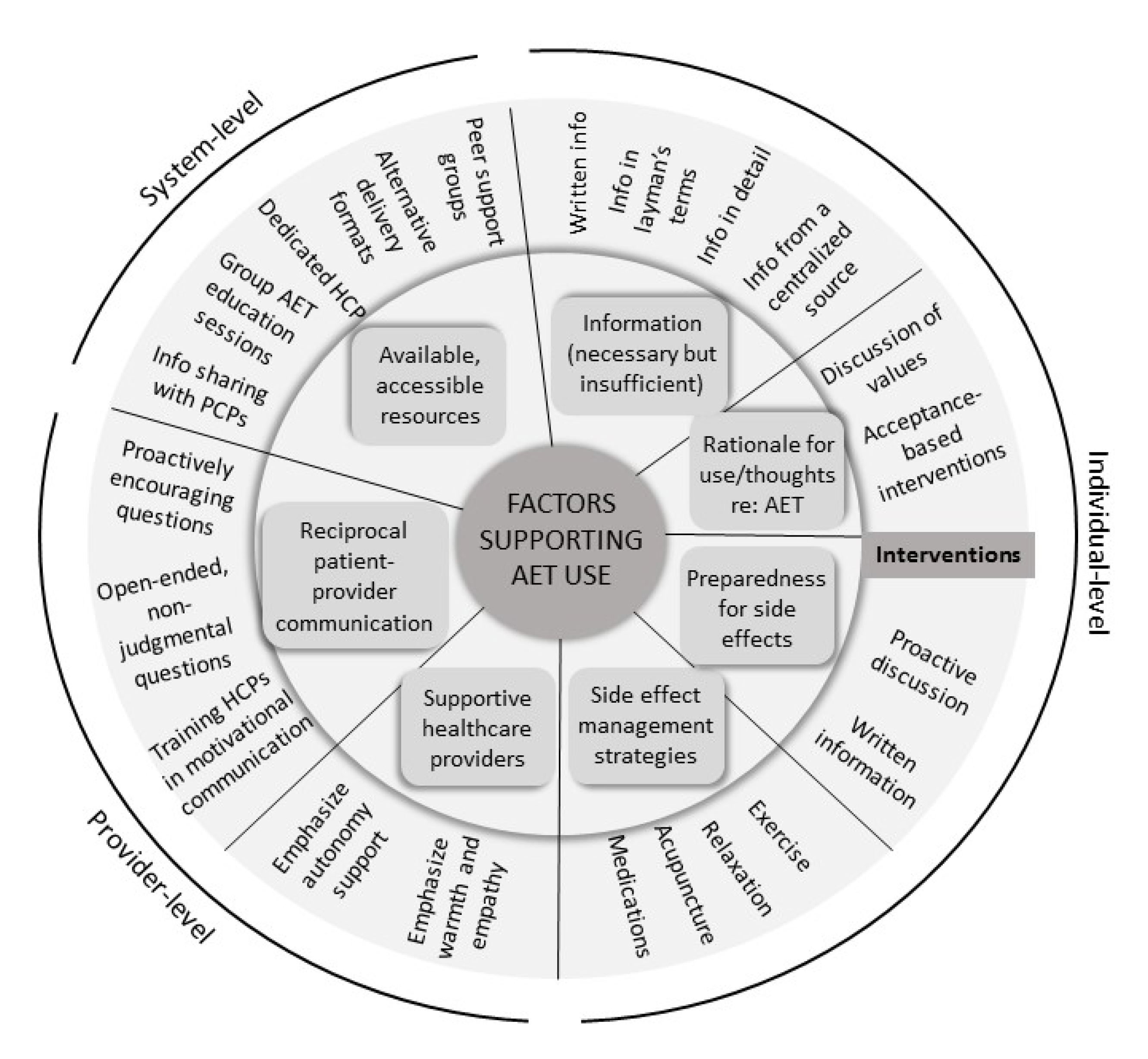

3.4. Comparison Across Groups

4. Discussion

Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Qualitative Interview Guide

- Tell me a bit about your cancer story—when did you find out?

- Probe: How was treatment for you?

- Probe: How have you been since?

- (Knowledge): I understand your doctor has prescribed this [medication] for you. Can you tell me why they prescribed this medication? What is its purpose?

- Probe: Where did you get your information about [name of drug] from?

- Probe: How did you feel about the information you got?

- (General experience with use): What has taking [medication] been like for you?

- Probe: What stands out about the experience the most?

- Probe: How was it compared to how you expected it would be?

- Probe: Is there anything you like about taking [name of drug]? Anything you dislike?

- (Decisions about use): Sometimes people decide not to take oral medications like these for breast cancer treatment. What are your plans for taking/why do you keep taking/why did you stop taking [medication]?

- Probe: What helped you to decide to keep taking it?

- Probe: What made you decide to stop taking it?

- (Barriers): What are some things that you think might make it difficult/has anything made it difficult to take [medication]?

- Probe: What are some things that might make it hard for other women to take [name of drug]?

- (Facilitators): What are some things you think might help you take/keep taking/restart [medication]?

- Probe: Was there anything that would have been helpful?

- Probe: What are some things that might make it easier for other women to take [name of drug]?

- (Intervention preferences):

- For all: One thing we are interested in doing is helping women who want to take their oral cancer therapies but are having trouble doing so. Based on your experience what kind of professional support or any support in general do you think would be helpful?

- For all: What would be your preferred way to communicate with someone who wanted to help you take your medications (e.g., phone, e-mail, in person)? Why?

- To get things started, I was wondering if you could tell me a little bit about your practice… how do you spend your time?

- (Knowledge): What sort of information do you provide your breast cancer patients when you prescribe adjuvant endocrine therapies for them?

- Follow-up: What other places do your patients get information from?

- Follow-up: What is your sense of the accuracy of the knowledge most patients have about these medications?

- Question 3 (general experience with use): How do your patients typically feel about taking adjuvant endocrine therapies?

- Follow-up: What do they like? What do they dislike?

- Question 4 (use): In your experience, how many women take them as prescribed?

- Question 5 (barriers): What are some things that make it difficult for women to take these medications?

- Question 5 (facilitators): What are some things that make it easier for women to take these medications?

- Question 6 (interventions): Have you ever tried strategies to help women adhere to prescribed adjuvant endocrine therapies?

- Follow-up: What have you tried?

- Follow-up: What has worked in the past, what hasn’t worked?

References

- Burstein, H.J.; Lacchetti, C.; Anderson, H.; Buchholz, T.A.; Davidson, N.E.; Gelmon, K.A.; Winer, E.P. Adjuvant endocrine therapy for women with hormone receptor-positive breast cancer: ASCO clinical practice guideline focused update. J. Clin. Oncol. 2019, 37, 423–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moon, Z.; Moss-Morris, R.; Hunter, M.S.; Carlisle, S.; Hughes, L.D. Barriers and facilitators of adjuvant hormone therapy adherence and persistence in women with breast cancer: A systematic review. Patient Pref. Adher. 2017, 11, 305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Sawesi, S.; Carpenter, J.S.; Jones, J. Reasons for nonadherence to tamoxifen and aromatase inhibitors for the treatment of breast cancer: A literature review. Clin. J. Onc. Nurs. 2014, 18, E50–E57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Lambert, L.K.; Balneaves, L.G.; Howard, A.F.; Gotay, C.C. Patient-reported factors associated with adherence to adjuvant endocrine therapy after breast cancer: An integrative review. Br. Cancer Res. Treat. 2018, 167, 615–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hershman, D.L.; Shao, T.; Kushi, L.H.; Buono, D.; Tsai, W.Y.; Fehrenbacher, L.; Neugut, A.I. Early discontinuation and non-adherence to adjuvant hormonal therapy are associated with increased mortality in women with breast cancer. Br. Cancer Res. Treat. 2011, 126, 529–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Hurtado-de-Mendoza, A.; Cabling, M.L.; Lobo, T.; Dash, C.; Sheppard, V.B. Behavioral interventions to enhance adherence to hormone therapy in breast cancer survivors: A systematic literature review. Clin. Br. Cancer 2016, 16, 247–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Ekinci, E.; Nathoo, S.; Korattyil, T.; Vadhariya, A.; Zaghloul, H.A.; Niravath, P.A.; Trivedi, M.V. Interventions to improve endocrine therapy adherence in breast cancer survivors: What is the evidence? J. Cancer Surviv. 2018, 12, 348–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czajkowski, S.M.; Powell, L.H.; Adler, N.; Naar-King, S.; Reynolds, K.D.; Hunter, C.M.; Charlson, M.E. From ideas to efficacy: The ORBIT model for developing behavioral treatments for chronic diseases. Health Psych. 2015, 34, 971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Cancer Institute. Qualitative Methods in Implementation Science. Available online: https://cancercontrol.cancer.gov/sites/default/files/2020-09/nci-dccps-implementationscience-whitepaper.pdf (accessed on 15 December 2020).

- Moon, Z.; Moss-Morris, R.; Hunter, M.S.; Hughes, L.D. Understanding tamoxifen adherence in women with breast cancer: A qualitative study. Br. J. Health Psych. 2017, 22, 978–997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brett, J.; Boulton, M.; Fenlon, D.; Hulbert-Williams, N.J.; Walter, F.M.; Donnelly, P.; Watson, E.K. Adjuvant endocrine therapy after breast cancer: A qualitative study of factors associated with adherence. Patient Pref. Adher. 2018, 12, 291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pellegrini, I.; Sarradon-Eck, A.; Ben Soussan, P.; Lacour, A.C.; Largillier, R.; Tallet, A.; Julian-Reynier, C. Women’s perceptions and experience of adjuvant tamoxifen therapy account for their adherence: Breast cancer patients’ point of view. Psycho-Oncology 2010, 19, 472–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verbrugghe, M.; Verhaeghe, S.; Decoene, E.; De Baere, S.; Vandendorpe, B.; Van Hecke, A. Factors influencing the process of medication (non-) adherence and (non-) persistence in breast cancer patients with adjuvant antihormonal therapy: A qualitative study. Eur. J. Cancer Care. 2017, 26, e12339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bluethmann, S.M.; Murphy, C.C.; Tiro, J.A.; Mollica, M.A.; Vernon, S.W.; Bartholomew, L.K. Deconstructing decisions to initiate, maintain, or discontinue adjuvant endocrine therapy in breast cancer survivors: A mixed-methods study. Onc. Nurs. Forum. 2017, 44, E101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wells, K.J.; Pan, T.M.; Vázquez-Otero, C.; Ung, D.; Ustjanauskas, A.E.; Muñoz, D.; Nuhaily, S. Barriers and facilitators to endocrine therapy adherence among underserved hormone-receptor-positive breast cancer survivors: A qualitative study. Supp. Care Cancer 2016, 24, 4123–4130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Tong, A.; Sainsbury, P.; Craig, J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): A 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int. J. Qual. Health Care. 2007, 19, 349–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Toivonen, K.I.; Carlson, L.E.; Rash, J.A.; Campbell, T.S. A survey of potentially modifiable patient-level factors associated with self-report and objectively measured adherence to adjuvant endocrine therapies after breast cancer. Patient Pref. Adher. Under review.

- Sandelowski, M. Whatever happened to qualitative description? Res. Nurs. Health. 2000, 23, 334–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saunders, B.; Sim, J.; Kingstone, T.; Baker, S.; Waterfield, J.; Bartlam, B.; Jinks, C. Saturation in qualitative research: Exploring its conceptualization and operationalization. Qual. Quant. 2018, 52, 1893–1907. [Google Scholar]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psych. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bengtsson, M. How to plan and perform a qualitative study using content analysis. NursingPlus Open. 2016, 2, 8–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Creswell, J.W.; Miller, D.L. Determining validity in qualitative inquiry. Theory Into Prac. 2000, 39, 124–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elo, S.; Kääriäinen, M.; Kanste, O.; Pölkki, T.; Utriainen, K.; Kyngäs, H. Qualitative content analysis: A focus on trustworthiness. SAGE Open. 2014, 4, 2158244014522633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambert, L.K.; Balneaves, L.G.; Howard, A.F.; Chia, S.K.; Gotay, C.C. Understanding adjuvant endocrine therapy persistence in breast Cancer survivors. BMC Cancer 2018, 18, 732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cahir, C.; Dombrowski, S.U.; Kelly, C.M.; Kennedy, M.J.; Bennett, K.; Sharp, L. Women’s experiences of hormonal therapy for breast cancer: Exploring influences on medication-taking behaviour. Supp. Care Cancer 2015, 23, 3115–3130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brauer, E.R.; Ganz, P.A.; Pieters, H.C. “Winging It”: How older breast cancer survivors persist with aromatase inhibitor treatment. J. Onc. Prac. 2016, 12, e991–e1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- AlOmeir, O.; Patel, N.; Donyai, P. Adherence to adjuvant endocrine therapy among breast cancer survivors: A systematic review and meta-synthesis of the qualitative literature using grounded theory. Supp. Care Cancer 2020, 28, 5075–5084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Humphries, B.; Collins, S.; Guillaumie, L.; Lemieux, J.; Dionne, A.; Provencher, L.; Lauzier, S. Women’s beliefs on early adherence to adjuvant endocrine therapy for breast cancer: A theory-based qualitative study to guide the development of community pharmacist interventions. Pharmacy 2018, 6, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Farias, A.J.; Ornelas, I.J.; Hohl, S.D.; Zeliadt, S.B.; Hansen, R.N.; Li, C.I.; Thompson, B. Exploring the role of physician communication about adjuvant endocrine therapy among breast cancer patients on active treatment: A qualitative analysis. Supp. Care Cancer 2017, 25, 75–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Lu, G.; Zheng, J.; Zhang, L. The effect of exercise on aromatase inhibitor-induced musculoskeletal symptoms in breast cancer survivors: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Supp. Care Cancer 2020, 28, 1587–1596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Battaglini, C.L.; Mills, R.C.; Phillips, B.L.; Lee, J.T.; Story, C.E.; Nascimento, M.G.; Hackney, A.C. Twenty-five years of research on the effects of exercise training in breast cancer survivors: A systematic review of the literature. World J. Clin. Onc. 2014, 5, 177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, G.S.; Kim, H.J.; Griffith, K.A.; Zhu, S.; Dorsey, S.G.; Renn, C.L. Interventions for the treatment of aromatase inhibitor–associated arthralgia in breast cancer survivors: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Cancer Nurs. 2017, 40, E26–E41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hutton, B.; Hersi, M.; Cheng, W.; Pratt, M.; Barbeau, P.; Yazdi, F.; Clemons, M. Comparing pharmacologics, natural health products, physical and behavioral interventions for management of hot flashes in patients with breast and prostate cancer: A systematic review with meta-analyses. Onc. Nurs. Forum. 2020, 47, E86. [Google Scholar]

- Colloca, L.; Miller, F.G. The nocebo effect and its relevance for clinical practice. Psychosom. Med. 2011, 73, 598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nestoriuc, Y.; Von Blanckenburg, P.; Schuricht, F.; Barsky, A.J.; Hadji, P.; Albert, U.S.; Rief, W. Is it best to expect the worst? Influence of patients’ side-effect expectations on endocrine treatment outcome in a 2-year prospective clinical cohort study. Ann. Onc. 2016, 27, 1909–1915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manaï, M.; van Middendorp, H.; Veldhuijzen, D.S.; Huizinga, T.W.; Evers, A.W. How to prevent, minimize, or extinguish nocebo effects in pain: A narrative review on mechanisms, predictors, and interventions. Pain Rep. 2019, 4, e699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shedden-Mora, M.C.; Pan, Y.; Heisig, S.R.; von Blanckenburg, P.; Rief, W.; Witzel, I.; Nestoriuc, Y. Optimizing expectations about endocrine treatment for breast cancer: Results of the randomized controlled PSY-BREAST trial. Clin. Psych. Eur. 2020, 2, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Costa, E.; Giardini, A.; Savin, M.; Menditto, E.; Lehane, E.; Laosa, O.; Marengoni, A. Interventional tools to improve medication adherence: Review of literature. Pat. Pref. Adher. 2015, 9, 1303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cuzick, J.; Sestak, I.; Cella, D.; Fallowfield, L. Treatment-emergent endocrine symptoms and the risk of breast cancer recurrence: A retrospective analysis of the ATAC trial. Lancet Onc. 2008, 9, 1143–1148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fontein, D.B.; Seynaeve, C.; Hadji, P.; Hille, E.T.; van de Water, W.; Putter, H.; Markopoulos, C. Specific adverse events predict survival benefit in patients treated with tamoxifen or aromatase inhibitors: An international tamoxifen exemestane adjuvant multinational trial analysis. J. Clin. Oncol. 2013, 31, 2257–2264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huober, J.; Cole, B.F.; Rabaglio, M.; Giobbie-Hurder, A.; Wu, J.; Ejlertsen, B.; Smith, I. Symptoms of endocrine treatment and outcome in the BIG 1-98 study. Br. Cancer Res. Treat. 2014, 143, 159–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fradelos, E.C.; Latsou, D.; Mitsi, D.; Tsaras, K.; Lekka, D.; Lavdaniti, M.; Papathanasiou, I.V. Assessment of the relation between religiosity, mental health, and psychological resilience in breast cancer patients. Contemp. Onc. 2018, 22, 172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Toledo, G.; Ochoa, C.Y.; Farias, A.J. Religion and spirituality: Their role in the psychosocial adjustment to breast cancer and subsequent symptom management of adjuvant endocrine therapy. Supp. Care Cancer 2021, 29, 3017–3024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iacorossi, L.; Gambalunga, F.; Fabi, A.; Giannarelli, D.; Marchetti, A.; Piredda, M.; De Marinis, M.G. Adherence to oral administration of endocrine treatment in patients with breast cancer: A qualitative study. Cancer Nurs. 2018, 41, E57–E63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, W.R.; Rollnick, S. Motivational Interviewing: Helping People Change; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Söderlund, L.L.; Madson, M.B.; Rubak, S.; Nilsen, P. A systematic review of motivational interviewing training for general health care practitioners. Patient Ed. Couns. 2012, 84, 16–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Collins, L.M. Optimization of Behavioral, Biobehavioral, and Biomedical Interventions: The Multiphase Optimization Strategy (MOST); Springer International Publishing AG: Cham, Switzerland, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Carlson, L.E. Screening alone is not enough: The importance of appropriate triage, referral, and evidence-based treatment of distress and common problems. J. Clin. Oncol. 2013, 31, 3616–3617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, L.M.; Murphy, S.A.; Strecher, V. The Multiphase Optimization Strategy (MOST) and the Sequential Multiple Assignment Randomized Trial (SMART): New methods for more potent eHealth interventions. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2007, 32, S112–S118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

| Demographic | Women Who Persisted | Women Who Discontinued |

|---|---|---|

| M(SD) | ||

| Age | 55.96 (8.48) | 64.33 (7.59) |

| Education (years) | 14.65 (2.29) | 13.93 (1.64) |

| Years since diagnosis | 2.59 (1.88) | 3.67 (1.68) |

| %(n) | ||

| Ethnicity | ||

| White | 82.6 (19) | 93.3 (14) |

| Asian | 13.0 (3) | 6.7 (1) |

| Mixed ethnic background | 4.3 (1) | - |

| Cancer stage | ||

| 0 | - | 7.7 (1) |

| 1 | 40.9 (9) | 30.8 (4) |

| 2 | 36.3 (8) | 46.2 (6) |

| 3 | 18.2 (4) | 15.4 (2) |

| 4 | 4.5 (1) | - |

| Primary treatment | ||

| Chemotherapy | 63.6 (14) | 40.0 (6) |

| Radiotherapy | 63.6 (14) | 53.3 (8) |

| Surgery | 100 (23) | 66.7 (10) |

| Current AET | ||

| Aromatase inhibitor | 52.2 (12) | - |

| Tamoxifen | 47.8 (11) | - |

| AETs used | ||

| Aromatase inhibitor | - | 26.7 (4) |

| Tamoxifen | - | 13.3 (2) |

| Both | - | 60.0 (9) |

| Themes (Subthemes) |

|---|

| Side Effects |

| Preparedness for side effects |

| “I’m going to have [hot flashes] eventually anyway, there’s no getting away from them. Because that’s how I looked at them, I’m just going through it now and probably handling it better than I might 10 years from now.” (Participant, age 47) “I still keep a lot of the literature on the medication itself. Because every time a new symptom comes, it’s like, “Was that expected, should I be worried or not be worried?” And so it’s kind of nice to go back to–they did mention it and they did think that it was going to be like this.” (Participant, age 41) |

| Management strategies |

| “As I started doing these exercises I got off the internet, it was like leaps and bounds. I could finally sleep almost through the whole night. And I wasn’t in pain.” (Participant, age 51) “I’ve done a lot of digging, and I can’t find anything. There’s a lot of anecdotal evidence, but… I take wheatgrass, a shot of it. I do not enjoy the flavor or anything about it.” (Participant, age 41) “A woman I was talking to the other day, she says that every time she takes her pill, she has to remind herself of the reason that she’s choosing to do this. Whereas someone else said, "Every time I take this pill, I have to remind myself that I’m being poisoned." So there is a lot to be said for framing it.” (Participant, age 51) |

| Rationale for use |

| “I mean, obviously it helps, right? Because the cancer is hormone dependent. So, I get that it’s definitely a good thing for me to take. But I think also me understanding that helps me to take it.” (Participant, age 51) “I have to be strong because I’m not just making the decision for myself, I’m making it for my family. In my mind it’s like, “Do I want to commit suicide or do I want to live?” I can’t be selfish because I’ve got a sore arm or a sore knee.” (Participant, age 51) “I think it’s saving my life [laughs], saving the cancer from coming back. I feel like I have that mindset so I wouldn’t think twice, no matter what the side effects were.” (Participant, age 70) |

| Experiences with the Healthcare System |

| Interactions with healthcare providers |

| “[The oncologist] just said, "You know what? You just have to give it a try, because it’s your protector. I know it’s brutal," but he said, "Just think of it as your protector." So it was totally how he delivered, absolutely.” (Participant, age 59) “[The oncologist] certainly left it in my ballpark, he never forced me to but he definitely talked to me about the pros and the cons. Yeah, he handled it really well”. (Participant, age 62) “I did not contact my oncologist about this, because I don’t feel like they listen to me anyway, so I just made my own decision.” (Participant, age 52) |

| Availability of resources |

| “There’s so much out there. There’s support groups, there’s people to talk to, there’s information, we have the internet. It’s there if you want it, I don’t think there needs to be more.” (Participant, age 47) “I’m pretty open to the idea of counseling–I think counseling was just something that was offered right upon diagnosis.” (Participant, age 51) |

| Themes (Subthemes) |

|---|

| Unmanageable side effects |

| “Because there was so much pain associated, I didn’t want to be touched by anybody, so then it affects all your relationships, right?” (Participant, age 59) “I decided I wanted to be able to golf and ski and do whatever without aching and feeling miserable. As I said, a shorter, better life than a longer one that wasn’t so good.” (Participant, age 77) “I tried many types and I have prescriptions for everything that I could possibly get to try to help that body pain and nothing works. With the result that I ended up with upper gut issues that I’m only just starting to be able to investigate now.” (Participant, age 50) |

| Reluctance |

| Information needs |

| “I think having more support on the drug side. Having more percentages and more data on Tamoxifen. How many people it’s worked for, how many people it hasn’t worked for, success rates, things like that. It just seemed like it was expected, and it didn’t seem that there was a lot of information that they could give me on the benefits of Tamoxifen. It was just kind of like “Here you go”. (Participant, age 68) “I think people assume that you understand what they’re talking about, but you really don’t, in layman’s terms. So, I can say that was a bit of a lack of information at that point.” (Participant, age 64) |

| Drawbacks of adjuvant endocrine therapy |

| “There is also all the research on women that had been taking it for umpteen years and still getting [cancer] recurrences. So, it just didn’t make any sense that I would have to feel that rotten if they couldn’t even guarantee that it would actually work.” (Participant, age 50) “To me Tamoxifen falls into the category of a pill for every ill. If you’ve got estrogen receptor positive breast cancer, they prescribe Tamoxifen for you, not even taking into any other factors into consideration.” (Participant, age 68) |

| Experiences with Healthcare Providers |

| “They did their best to make sure that I had everything that they could think of. It wasn’t their fault, and it wasn’t that they didn’t try hard. They sure did.” (Participant, age 67) “I would have a whole bunch of questions written down when I would go in to see [oncologist]. I’d say, “Okay, I have a list of questions for you”. He would say things like “Well, how many?”, and stuff like that. So, I just found him quite abrupt, and not somebody that I really want on my healthcare team.” (Participant, age 68) “I knew that [AET use] was always up to me, and I was thankful for the information that they provided. But also thankful for the fact that they left the decision up to me.” (Participant, age 67) |

| Contextual Factors |

| “Probably at 40, I would’ve had kids and at 69, I don’t have a lot of responsibilities. You know, I’m over the hill and so I didn’t feel the need to struggle with it as the same as I would’ve if I was younger.” (Participant, age 69) “So out of financial concern, I was working fulltime. The financial concern was causing me to stop taking my medication early, just in order to keep my job.” (Participant, age 57) “Having [cancer] come back a second time-I was more open to taking medications if they were going to be helpful.” (Participant, age 64) |

| Themes |

|---|

| Barriers at Patient-and System-Level |

| “In theory, cost shouldn’t be a barrier because the medications are provided free of charge, but logistically there is lots of costs. Patients have to travel, like driving in from a ranch. It’s a lot of money and gas.” (Pharmacist) “Unless they’re calling for a refill, there would be no way of following them closely, so we do have a certain percentage of patients that are lost through this.” (Pharmacist) “The other thing that I think is helpful, and it can be harmful for people, is the internet too. There are a lot of chat groups, these sort of things, where good information but, sometimes wrong information, misinformation is being communicated to individuals. As things get a little bit more electronic based, I spend a lot more time correcting misinformation than I did ever before.” (Oncologist) |

| Side Effect Management |

| “Light to moderate or weight bearing exercise is really good. So non-pharmacological measures first. If that doesn’t work, then of course pharmacological measures, such as using Tylenol Arthritis or anti-inflammatories if necessary.” (Pharmacist) “I think the fact that women after breast cancer have a lot of issues not only with the side effects of medication but also the feeling of isolation, depression sometimes, grieving, the fact that they often struggle with weight. They may have struggled with weight as a risk factor for their cancer. I think that the idea of having a more coordinated approach to offer exercise and coaching essentially for physical health would be another significant help.” (Oncologist) “But if [side effects] get actually worrisome, we usually use venlafaxine and sometimes SSRIs. That’s only for when they have pretty much bothersome hot flashes.” (Oncology resident) |

| Patient-Provider Interactions |

| “So I try and give people things that they can actually do. Because I feel like that’s a little more empowering, rather than just saying “Hey, here’s the medication.” (Oncology resident) “I feel that part of it will also come down to how you present it initially. So part of my initial talk to [patients] is like, “I’m gonna see you in 3 months after I start it, but I really want you to call me if you notice anything.” And I tend to try and get my patients to err on the side of calling rather than not calling.” (Oncology resident) “There’s two type of patients. There is one who won’t say anything and struggle on and struggle on and doesn’t let the clinic know. There is another patient who will very quickly verbalize that and need help or demand a change, because you can’t tolerate it, it’s affected her quality of life.” (Pharmacist) “Although there’s no food restrictions, with food on any of these agents, I’m a big proponent of–we have to keep it simple. The more restrictions and complications that we add, we risk people not taking it, and then of course we’ve lost all potential benefits of taking it.” (Pharmacist) |

| Themes | Women Who Persisted with AET (n = 23) | Women Who Discontinued AET (n = 15) | Healthcare Providers Who Manage AET (n = 9) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Side effects | Women were prepared to deal with side effects | Side effects were overwhelming and interfered with quality of life | Side effects are a key factor associated with AET discontinuation |

| Side effect management strategies | Women had strategies to successfully manage side effects (e.g., exercise) | Women were unable to find effective side effect management strategies | HCPs recommended behavioural (e.g., exercise) and pharmacological strategies |

| Information | Women wanted more, detailed, relevant, and understandable information | HCPs viewed providing information as a key strategy for promoting AET use | |

| Thoughts related to AET use | Women emphasized the life-saving potential of AET and personal reasons for use | Women emphasized that AET was not guaranteed to work and feared long-term effects (e.g., bone loss) | HCPs recognized patients could have pre-existing negative bias toward AET |

| Communication with healthcare providers | Supportive HCPs could be a key factor in continuing AET | Women appreciated autonomy; they were frustrated when they perceived HCPs as rushed or un-responsive | Communication needs to be reciprocal to be effective |

| Experiences with the healthcare system | Resources were available to support women in AET use | Healthcare system constraints make it difficult for HCPs to address concerns thoroughly | |

| Contextual factors | Being older, pre-existing illness, and having to work could make AET seem less worthwhile | Peripheral out-of-pocket costs could still impact AET use Offering mailed prescriptions programs could help |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Toivonen, K.I.; Oberoi, D.; King-Shier, K.; Piedalue, K.-A.L.; Rash, J.A.; Carlson, L.E.; Campbell, T.S. Both “Vitamin L for Life” and “One Milligram of Satan”: A Multi-Perspective Qualitative Exploration of Adjuvant Endocrine Therapy Use after Breast Cancer. Curr. Oncol. 2021, 28, 2496-2515. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol28040227

Toivonen KI, Oberoi D, King-Shier K, Piedalue K-AL, Rash JA, Carlson LE, Campbell TS. Both “Vitamin L for Life” and “One Milligram of Satan”: A Multi-Perspective Qualitative Exploration of Adjuvant Endocrine Therapy Use after Breast Cancer. Current Oncology. 2021; 28(4):2496-2515. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol28040227

Chicago/Turabian StyleToivonen, Kirsti I., Devesh Oberoi, Kathryn King-Shier, Katherine-Ann L. Piedalue, Joshua A. Rash, Linda E. Carlson, and Tavis S. Campbell. 2021. "Both “Vitamin L for Life” and “One Milligram of Satan”: A Multi-Perspective Qualitative Exploration of Adjuvant Endocrine Therapy Use after Breast Cancer" Current Oncology 28, no. 4: 2496-2515. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol28040227

APA StyleToivonen, K. I., Oberoi, D., King-Shier, K., Piedalue, K.-A. L., Rash, J. A., Carlson, L. E., & Campbell, T. S. (2021). Both “Vitamin L for Life” and “One Milligram of Satan”: A Multi-Perspective Qualitative Exploration of Adjuvant Endocrine Therapy Use after Breast Cancer. Current Oncology, 28(4), 2496-2515. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol28040227