Canadian Resources, Programs, and Models of Care to Support Cancer Survivors’ Transition beyond Treatment: A Scoping Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Protocol and Registration

2.2. Inclusion & Exclusion Criteria

2.3. Search Strategy

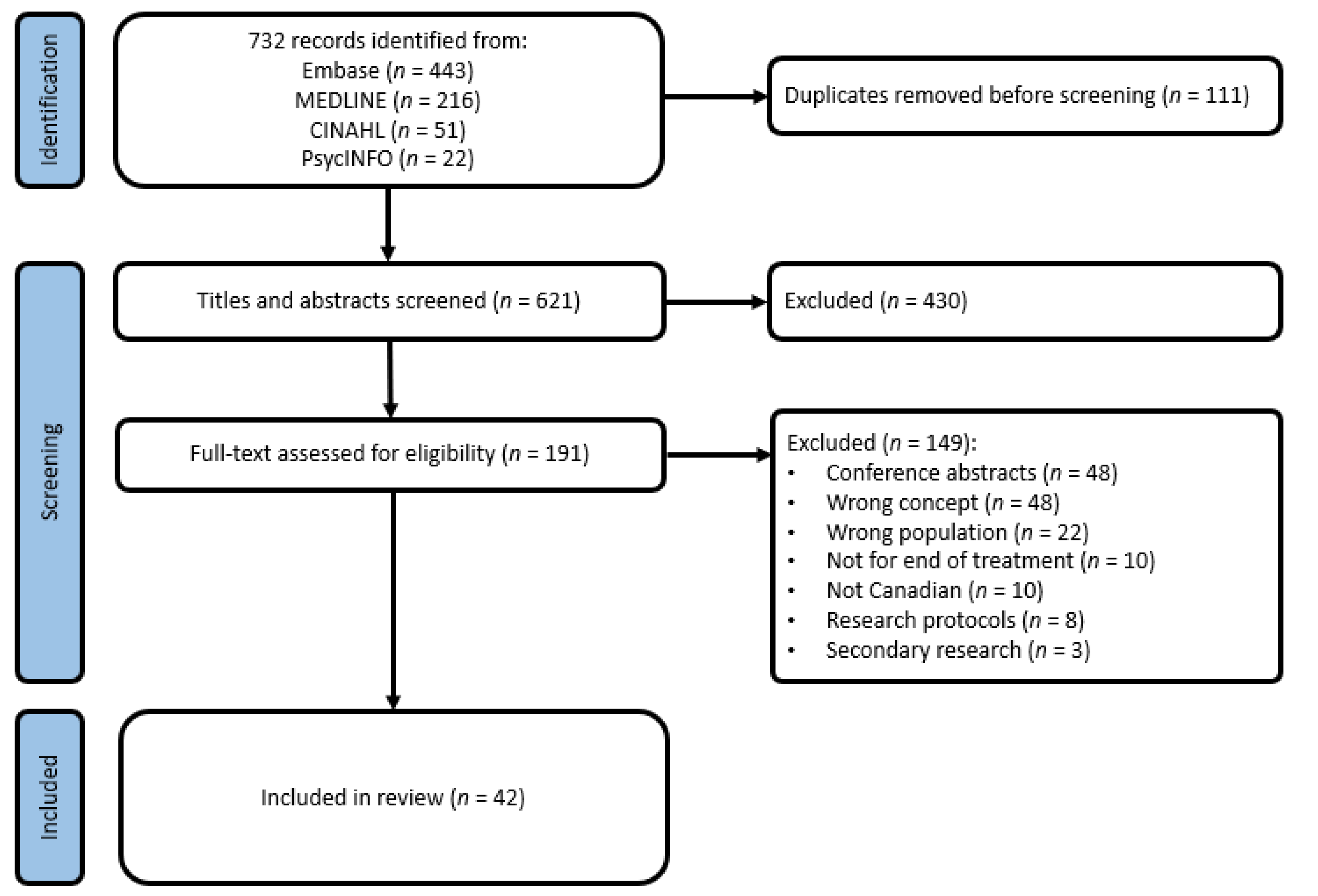

2.4. Study Selection & Data Extraction

2.5. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Models of Care

3.2. Supportive Care Interventions

3.3. Alignment with CCO & CAPO/CPAC Recommendations

4. Discussion

4.1. Implications for Practice and Research

4.2. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Brenner, D.R.; Weir, H.K.; Demers, A.; Ellison, L.F.; Louzado, C.; Shaw, A.E.; Turner, D.; Woods, R.R.; Smith, L.M. Projected estimates of cancer in Canada in 2020. CMAJ 2020, 2, E199–E205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brearley, S.G.; Stamataki, Z.; Addington-Hall, J.; Foster, C.; Hodges, L.; Jarrett, N.; Richardson, A.; Scott, I.; Sharpe, M.; Stark, D.; et al. The physical and practical problems experienced by cancer survivors: A rapid review and synthesis of the literature. Eur. J. Oncol. Nurs. 2011, 15, 204–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Canadian Partnership Against Cancer. Living with Cancer: A Report on the Patient Experience. Available online: https://www.partnershipagainstcancer.ca/topics/living-with-cancer-report-patient-experience/# (accessed on 9 May 2021).

- Follow-Up Model of Care for Cancer Survivors: Recommendations for the Delivery of Follow-up Care for Cancer Survivors in Ontario. Available online: https://www.cancercareontario.ca/sites/ccocancercare/files/guidelines/full/FollowUpModelOfCareCancerSurvivors.pdf (accessed on 9 May 2021).

- Institute of Medicine; National Research Council. From Cancer Patient to Cancer Survivor: Lost in Transition; The National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2006; 534p. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howell, D.H.; Oliver, T.K.; Chulak, T.; Mayon, S.; Aubin, M.; Chasen, M.; Earle, C.C.; Friedman, A.J.; Jones, G.W.; Jones, J.M.; et al. A Pan-Canadian Practice Guideline Pan-Canadian Guidance on Organization and Structure of Survivorship Services and Psychosocial-Supportive Care Best Practices for Adult Cancer Survivors; Canadian Partnership Against Cancer (Cancer Journey Action Group) and the Canadian Association of Psychosocial Oncology: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Sussman, J.S.; Grunfeld, E.; Howell, D.; Gage, C.; Keller-Olaman, S.; Brouwers, M. Models of Care for Cancer Survivorship. In Program in Evidence-Based Care. Evidence-Based Series; Cancer Care Ontario: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2017; Volume 26. [Google Scholar]

- Mittmann, N.; Beglaryan, H.; Liu, N.; Seung, S.J.; Rahman, F.; Gilbert, J.; Ross, J.; Rossi, S.D.; Earle, C.; Grunfeld, E.; et al. Evaluating the impact of survivorship models on health system resources and costs. J. Clin. Oncol. 2018, 36, 1-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, D.K.; Nasso, S.F.; Earp, J.A. Defining cancer survivors, their needs, and perspectives on survivorship health care in the USA. Lancet Oncol. 2017, 18, e11–e18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burg, M.A.; Adorno, G.; Lopez, E.D.; Loerzel, V.; Stein, K.; Wallace, C.; Sharma, D.K.B. Current unmet needs of cancer survivors: Analysis of open-ended responses to the American Cancer Society Study of Cancer Survivors II. Cancer 2015, 121, 623–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, M.D.J.; Godfrey, C.; McInerney, P.; Munn, Z.; Tricco, A.C.; Khalil, H. Chapter 11: Scoping Reviews (2020 version). In JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis; Aromataris, E., Munn, Z., Eds.; JBI: Adelaide, Australia, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O’Brien, K.K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Moher, D.; Peters, M.D.J.; Horsley, T.; Weeks, L.; et al. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation. Ann. Intern. Med. 2018, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Veritas Health Innovation. Covidence Systematic Review Software; Veritas Health Innovation Ltd.: Melbourne, Australia, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Bender, J.; Wiljer, D.; Sawka, A.; Tsang, R.; Alkazaz, N.; Brierley, J.; Bender, J.L.; Sawka, A.M.; Brierley, J.D. Thyroid cancer survivors’ perceptions of survivorship care follow-up options: A cross-sectional, mixed-methods survey. Support. Care Cancer 2016, 24, 2007–2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, M.; De Rossi, S.; Sussman, J. Supporting models to transition breast cancer survivors to primary care: Formative evaluation of a cancer care Ontario initiative. J. Oncol. Pract. 2015, 11, e288–e295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hugh-Yeun, K.; Kumar, D.; Moghaddamjou, A.; Ruan, J.; Cheung, W.; Ruan, J.Y.; Cheung, W.Y. Young adult cancer survivors’ follow-up care expectations of oncologists and primary care physicians. J. Cancer Surviv. 2017, 11, 295–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh-Carlson, S.; Wong, F.; Oshan, G. Evaluation of the delivery of survivorship care plans for South Asian female breast cancer survivors residing in Canada. Curr. Oncol. 2018, 25, e265–e274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Railton, C.; Lupichuk, S.; Jennifer, M.; Zhong, L.; Ko, J.J.; Walley, B.; Joy, A.A.; Giese-Davis, J. Discharge to primary care for survivorship follow-up: How are patients with early-stage breast cancer faring? JNCCN 2015, 13, 762–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sisler, J.J.; Taylor-Brown, J.; Nugent, Z.; Bell, D.; Khawaja, M.; Czaykowski, P.; Wirtzfeld, D.; Park, J.; Ahmed, S. Continuity of care of colorectal cancer survivors at the end of treatment: The oncology-primary care interface. J. Cancer Surviv. 2012, 6, 468–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Urquhart, R.; Lethbridge, L.; Porter, G.A. Patterns of cancer centre follow-up care for survivors of breast, colorectal, gynecologic, and prostate cancer. Curr. Oncol. 2017, 24, 360–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goldenberg, B.A.; Carpenter-Kellett, T.; Gingerich, J.R.; Nugent, Z.; Sisler, J.J. Moving forward after cancer: Successful implementation of a colorectal cancer patient-centered transitions program. J. Cancer Surviv. Res. Pract. 2020, 14, 4–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liska, C.M.; Morash, R.; Paquet, L.; Stacey, D. Empowering cancer survivors to meet their physical and psychosocial needs: An implementation evaluation. Can. Oncol. Nurs. J. 2018, 28, 76–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jammu, A.; Chasen, M.; van Heest, R.; Hollingshead, S.; Kaushik, D.; Gill, H.; Bhargava, R. Effects of a Cancer Survivorship Clinic-preliminary results. Support. Care Cancer 2020, 28, 2381–2388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McBride, M.L.; Groome, P.A.; Decker, K.; Kendell, C.; Jiang, L.; Whitehead, M.; Li, D.; Grunfeld, E. Adherence to quality breast cancer survivorship care in four Canadian provinces: A CanIMPACT retrospective cohort study. Bmc Cancer 2019, 19, 659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaudine, A.; Sturge-Jacobs, M.; Kennedy, M. The experience of waiting and life during breast cancer follow-up. Res. Theory Nurs. Pract. 2003, 17, 153–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wiljer, D.; Urowitz, S.; Jones, J.; Kornblum, A.; Secord, S.; Catton, P. Exploring the use of the survivorship consult in providing survivorship care. Support. Care Cancer 2013, 21, 2117–2124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, T.L.; Yakiwchuk, C.V.; Griffin, K.L.; Gra, R.E.; Fitch, M.I. Survivor Dragon Boating: A Vehicle to Reclaim and Enhance Life After Treatment for Breast Cancer. Health Care Women Int. 2007, 28, 122–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peddle, C.J.; Au, H.J.; Courneya, K.S. Associations between exercise, quality of life, and fatigue in colorectal cancer survivors. Dis. Colon Rectum 2008, 51, 1242–1248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vallance, J.K.H.; Courneya, K.S.; Plotnikoff, R.C.; Yasui, Y.; Mackey, J.R. Randomized controlled trial of the effects of print materials and step pedometers on physical activity and quality of life in breast cancer survivors. J. Clin. Oncol. 2007, 25, 2352–2359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norris, M.K.; Bell, G.J.; North, S.; Courneya, K.S. Effects of resistance training frequency on physical functioning and quality of life in prostate cancer survivors: A pilot randomized controlled trial. Prostate Cancer Prost. Dis. 2015, 18, 281–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vallance, J.; Lavallee, C.; Culos-Reed, N.; Trudeau, M. Rural and small town breast cancer survivors’ preferences for physical activity. Int. J. Behav. Med. 2013, 20, 522–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunet, J.; St-Aubin, A. Fostering positive experiences of group-based exercise classes after breast cancer: What do women have to say? Disabil. Rehabil. 2016, 38, 1500–1508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farris, M.S.; Kopciuk, K.A.; Courneya, K.S.; McGregor, S.E.; Wang, Q.; Friedenreich, C.M. Associations of postdiagnosis physical activity and change from prediagnosis physical activity with quality of life in prostate cancer survivors. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 2017, 26, 179–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trinh, L.; Arbour-Nicitopoulos, K.P.; Sabiston, C.M.; Berry, S.R.; Loblaw, A.; Alibhai, S.M.H.; Jones, J.M.; Faulkner, G.E. RiseTx: Testing the feasibility of a web application for reducing sedentary behavior among prostate cancer survivors receiving androgen deprivation therapy. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2018, 15, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fillion, L.; Gagnon, P.; Leblond, F.; Gelinas, C.; Savard, J.; Dupuis, R.; Duval, K.; Larochelle, M. A brief intervention for fatigue management in breast cancer survivors. Cancer Nurs. 2008, 31, 145–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tracy, M.; McDivitt, K.; Ryan, M.; Tomlinson, J.; Brotto, L.A. Feasibility of a Sexual Health Clinic Within Cancer Care. Cancer Nurs. 2016, 39, E32–E42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kwong, S.; Bedard, A. BE ACTIVE: An Education Program for Chinese Cancer Survivors in Canada. J. Cancer Educ. Off. J. Am. Assoc. Cancer Educ. 2016, 31, 605–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galica, J.; Giroux, J.; Francis, J.-A.; Maheu, C. Coping with fear of cancer recurrence among ovarian cancer survivors living in small urban and rural settings: A qualitative descriptive study. Eur. J. Oncol. Nurs. 2020, 44, 101705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Easley, J.; Miedema, B. Rehabilitation After Breast Cancer: Recommendations from Young Survivors. Rehabil. Nurs. 2012, 37, 163–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammond, C.; Thomas, R.; Gifford, W.; Poudrier, J.; Hamilton, R.; Brooks, C.; Morrison, T.; Scott, T.; Warner, D. Cycles of silence: First Nations women overcoming social and historical barriers in supportive cancer care. Psycho-Oncol. 2017, 26, 191–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miedema, B.; Easley, J. Barriers to rehabilitative care for young breast cancer survivors: A qualitative understanding. Support. Care Cancer 2012, 20, 1193–1201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bilodeau, K.; Tremblay, D.; Durand, M.J. Gaps and delays in survivorship care in the return-to-work pathway for survivors of breast cancer-a qualitative study. Curr. Oncol. 2019, 26, e414–e417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dawe, D.E.; Bennett, L.R.; Kearney, A.; Westera, D. Emotional and informational needs of women experiencing outpatient surgery for breast cancer. Can. Oncol. Nurs. J. 2014, 24, 20–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shannon, C.S.; Bourque, D. Overlooked and underutilized: The critical role of leisure interventions in facilitating social support throughout breast cancer treatment and recovery. Soc. Work Health Care 2005, 42, 73–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saroa, O.; Molzahn, A.E.; Northcott, H.C.; Schmidt, K.; Ghosh, S.; Olson, K. A Survey of Information Needs and Preferences of Patients With Head and Neck Cancer. Oncol. Nurs. Forum 2018, 45, 761–774. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, J.M.; Fitch, M.; Bongard, J.; Maganti, M.; Gupta, A.; D’Agostino, N.; Korenblum, C. The needs and experiences of post-treatment adolescent and young adult cancer survivors. J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9, 1444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gifford, W.; Thomas, O.; Thomas, R.; Grandpierre, V.; Ukagwu, C. Spirituality in cancer survivorship with First Nations people in Canada. Support. Care Cancer 2019, 27, 2969–2976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gall, T.L. The role of religious coping in adjustment to prostate cancer. Cancer Nurs. 2004, 27, 454–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alimujiang, A.; Khoja, L.; Wiensch, A.; Pike, M.C.; Webb, P.M.; Chenevix-Trench, G.; Chase, A.; Richardson, J.; Pearce, C.L. “I am not a statistic” ovarian cancer survivors’ views of factors that influenced their long-term survival. Gynecol. Oncol. 2019, 461–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chongya, N.; Eng, L.; Xin, Q.; Xiaowei, S.; Espin-Garcia, O.; Yuyao, S.; Pringle, D.; Mahler, M.; Halytskyy, O.; Charow, R.; et al. Lifestyle Behaviors in Elderly Cancer Survivors: A Comparison With Middle-Age Cancer Survivors. J. Oncol. Pract. 2015, 11, e450–e459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collie, K.; McCormick, J.; Waller, A.; Railton, C.; Shirt, L.; Chobanuk, J.; Taylor, A.; Lau, H.; Hao, D.; Walley, B.; et al. Qualitative evaluation of care plans for Canadian breast and head-and-neck cancer survivors. Curr. Oncol. 2014, 21, e18–e28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haq, R.; Heus, L.; Baker, N.A.; Dastur, D.; Leung, F.-H.; Leung, E.; Li, B.; Vu, K.; Parsons, J.A. Designing a multifaceted survivorship care plan to meet the information and communication needs of breast cancer patients and their family physicians: Results of a qualitative pilot study. BMC Med. Inform. Decis. Mak. 2013, 13, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowler, M.; Dehek, R.; Thomas, E.; Ngo, K.; Grose, L. Evaluating the Impact of Post-Treatment Self-Management Guidelines for Prostate Cancer Survivors. J. Med. Imaging Radiat. Sci. 2019, 50, 398–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chahine, S.; Robin, U. A cross-sectional population-based survey looking at the impact of cancer survivorship care plans on meeting the needs of cancer survivors. Support. Care Cancer 2019, 27 (Suppl. S1), S217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boekhout, A.; Maunsell, E.; Pond, G.; Julian, J.; Coyle, D.; Levine, M.; Grunfeld, E.; Boekhout, A.H.; Pond, G.R.; Julian, J.A.; et al. A survivorship care plan for breast cancer survivors: Extended results of a randomized clinical trial. J. Cancer Surviv. 2015, 9, 683–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cyr, M.-P.; Dumoulin, C.; Bessette, P.; Pina, A.; Gotlieb, W.H.; Lapointe-Milot, K.; Mayrand, M.-H.; Morin, M. Feasibility, acceptability and effects of multimodal pelvic floor physical therapy for gynecological cancer survivors suffering from painful sexual intercourse: A multicenter prospective interventional study. Gynecol. Oncol. 2020, 159, 778–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodgson, D.C.; Grunfeld, E.; Gunraj, N.; Del Giudice, L. A population-based study of follow-up care for Hodgkin lymphoma survivors: Opportunities to improve surveillance for relapse and late effects. Cancer 2010, 116, 3417–3425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jhaveri, K.; Cohen, J.A.; Barulich, M.; Levin, A.O.; Goyal, N.; Loveday, T.; Chesney, M.A.; Shumay, D.M. “Soup cans, brooms, and Zoom”: Rapid conversion of a cancer survivorship program to telehealth during COVID-19. Psycho-Oncol. 2020, 29, 1424–1426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keesing, S.; McNamara, B.; Rosenwax, L. Cancer survivors’ experiences of using survivorship care plans: A systematic review of qualitative studies. J. Cancer Surviv. 2015, 9, 260–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinto, B.M.; Floyd, A. Theories Underlying Health Promotion Interventions Among Cancer Survivors. Semin. Oncol. Nurs. 2008, 24, 153–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Graves, K.D. Social cognitive theory and cancer patients’ quality of life: A meta-analysis of psychosocial intervention components. Health Psychol. 2003, 22, 210–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thompson, C.A.; Charlson, M.E.; Schenkein, E.; Wells, M.T.; Furman, R.R.; Elstrom, R.; Ruan, J.; Martin, P.; Leonard, J.P. Surveillance CT scans are a source of anxiety and fear of recurrence in long-term lymphoma survivors. Ann. Oncol. 2010, 21, 2262–2266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berry-Stoelzle, M.A.; Mark, A.C.; Kim, P.; Daly, J.M. Anxiety-Related Issues in Cancer Survivorship. J. Patient Cent Res. Rev. 2020, 7, 31–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziner, K.W.; Sledge, G.W.; Bell, C.J.; Johns, S.; Miller, K.D.; Champion, V.L. Predicting Fear of Breast Cancer Recurrence and Self-Efficacy in Survivors by Age at Diagnosis. Oncol. Nurs. Forum 2012, 39, 287–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Romkey-Sinasac, C.; Saunders, S.; Galica, J. Canadian Resources, Programs, and Models of Care to Support Cancer Survivors’ Transition beyond Treatment: A Scoping Review. Curr. Oncol. 2021, 28, 2134-2145. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol28030198

Romkey-Sinasac C, Saunders S, Galica J. Canadian Resources, Programs, and Models of Care to Support Cancer Survivors’ Transition beyond Treatment: A Scoping Review. Current Oncology. 2021; 28(3):2134-2145. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol28030198

Chicago/Turabian StyleRomkey-Sinasac, Claudia, Stephanie Saunders, and Jacqueline Galica. 2021. "Canadian Resources, Programs, and Models of Care to Support Cancer Survivors’ Transition beyond Treatment: A Scoping Review" Current Oncology 28, no. 3: 2134-2145. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol28030198

APA StyleRomkey-Sinasac, C., Saunders, S., & Galica, J. (2021). Canadian Resources, Programs, and Models of Care to Support Cancer Survivors’ Transition beyond Treatment: A Scoping Review. Current Oncology, 28(3), 2134-2145. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol28030198