Hypertension in Frail Patients

Introduction

What is frailty?

What is the current evidence on hypertension in frail patients in the literature?

Evidence from observational studies

Evidence from randomised controlled trials

Conclusions on current evidence

What can be recommended for clinical practice?

- The HYVET and SPRINT trials have shown that, for their participants, even the oldest old, antihypertensive treatment is beneficial for important outcomes – outcomes that are important even in the last years of life [7,8,9,10]. However, it is important to note that the older participants in these trials were relatively healthy, fit and non-frail. Thus, in such patients, rigorous antihypertensive treatment is an important therapeutic strategy to prevent cardiovascular morbidity and mortality. As cardiovascular morbidity is a trigger of frailty and disability, it has to be presumed that rigorous antihypertensive treatment in these patients prevents frailty and disability, but evidence-based proof for this statement is pending.

- For patients who are already frail, evidence on antihypertensive treatment is sparse. Current recommendations for target blood pressure levels depend rather on remaining life span and on concomitant chronic diseases than on frailty per se [12]. Among geriatricians, it is widely accepted that tight blood pressure control <140/90 mm Hg is no longer recommended if the remaining life span is less than 1 to 2 years [13]. Frailty is a marker of a reduced remaining life span. To determine target blood pressure in frail patients, the remaining life span has to be estimated based on life-limiting diseases. In frail hypertensive patients with a markedly reduced life span, the target blood pressure goal may be gradually increased with a shorter life span. Of course, there are exceptions to this rule of thumb depending on concomitant chronic diseases. For example, patients with severe systolic heart failure need continuation of their heart failure medication, and low blood pressures are preferable in most of these patients even though their life span is markedly reduced, because discontinuation of the drugs could lead to an increase in the symptom burden.

- Current recommendations for target blood pressure levels in frail patients also depend on the tolerability of antihypertensive drugs [12]. If there is already relevant vascular disease, tight blood pressure control may lead to organ dysfunction distal to macroand/or microvascular stenoses. For example, in patients with vascular leukoencephalopathy, vertigo and/or cognitive dysfunction may be encountered with a too tight blood pressure control. As another example, patients with coronary artery disease may be prone to myocardial ischaemia and increased mortality if diastolic blood pressure is lower than 50–60 mm Hg [14]. Thus, a too tight blood pressure control in frail hypertensive patients with vascular disease may lead to critical organ hypoperfusion. Higher blood pressure goals have to be accepted in some of these patients.

- Orthostatic hypotension is frequently found among frail hypertensive patients with multiple comorbidities and polypharmacy [15]. Thus, blood pressure should always be measured in both the sitting (or lying) and the standing position in frail patients. In general, blood pressure measurement is recommended in the sitting/lying position and then 1 and 3 minutes after standing up. If there is orthostatic hypotension (generally defined as drop of the systolic blood pressure ≥20 mm Hg and/or the diastolic blood pressure ≥10 mm Hg after standing up), the first step, besides support stockings and the instruction in the usual behavioural rules, is to do a polypharmacy check. Most frail patients are on several drugs, and many of these drugs may lead to orthostatic hypotension. Of course, all antihypertensive drugs may lead to orthostatic hypotension. However, before reducing the antihypertensive therapy, check for other drugs that may induce orthostatic hypotension, such as antidepressants, dopamine and its agonists, and opiates. Nearly all antidepressants may provoke orthostatic hypotension, but tricyclic and heterocyclic (i.e., trazodone) antidepressants and the monoamine oxidase inhibitors are the worst. In most instances, the antidepressant may be replaced by another. If orthostatic hypotension occurs with dopamine, domperidone may be tried 30 minutes before the intake of dopamine (domperidone is a peripheral dopamine antagonist that does not cross the blood-brain barrier). Among the antihypertensive drugs, alpha blockers are the worst; almost always they are easily replaceable. Remember that tamsulosin is an alpha-blocking drug, which can lead to orthostatic hypotension. Sometimes, it may be advisable to replace it with a 5-alpha-reductase inhibitor in patients with benign prostatic hyperplasia and orthostatic hypotension. Diuretics frequently induce orthostatic hypotension; therefore, they should be periodically adjusted, especially during summertime.

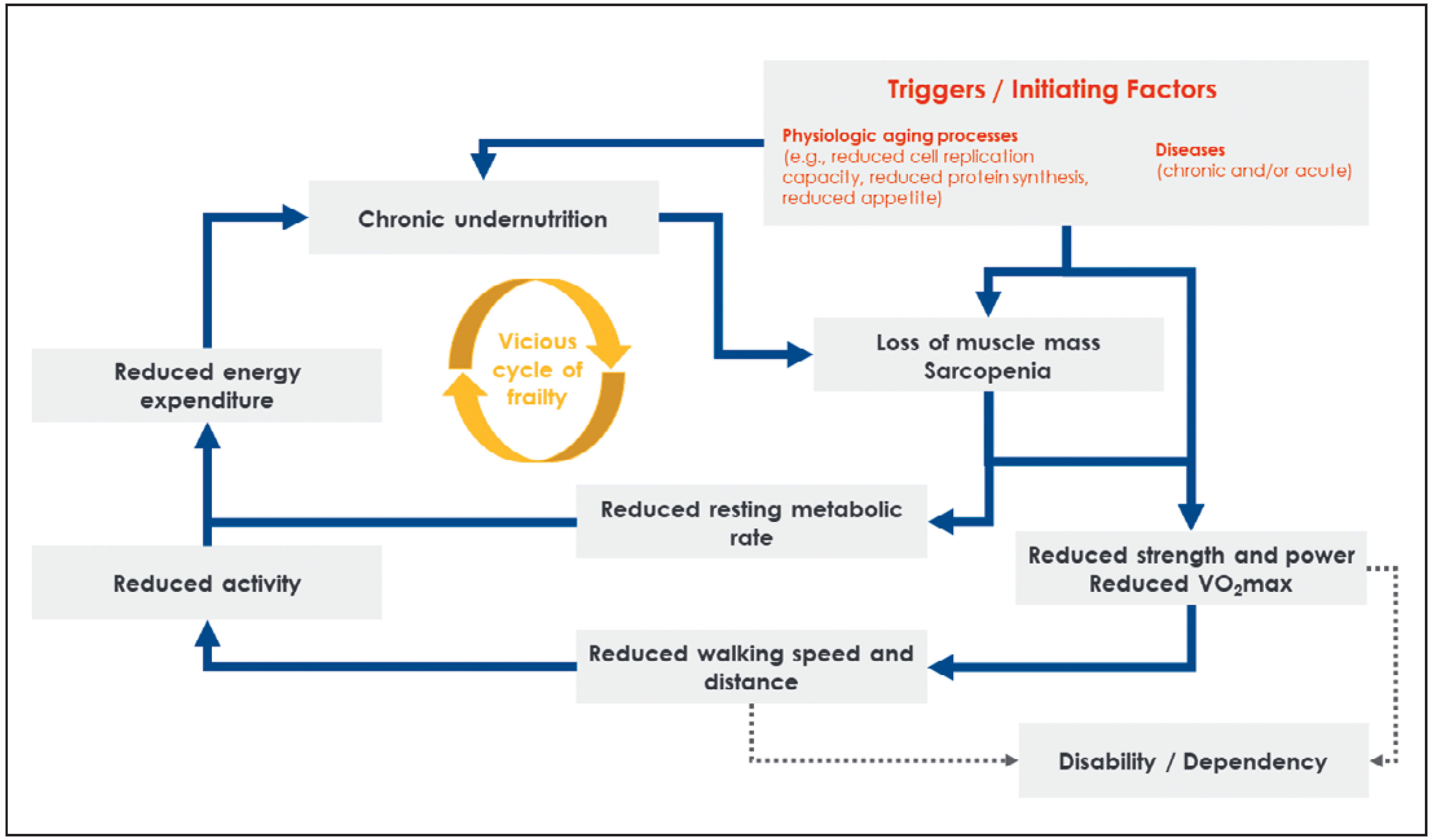

- Last but not least, frailty is considered to be a potentially reversible condition. Therefore, the treating physician should always evaluate whether the diseases that promoted frailty are treatable. For example, severe aortic stenosis may induce frailty; with aortic valve replacement, frailty may completely vanish [16]. If there is no treatable cause of frailty, the physician should always evaluate whether geriatric rehabilitation is indicated. The intensive physical training together with nutritional intervention, which are part of any geriatric rehabilitation, may reverse the vicious cycle of frailty and prevent its progression to disability and care dependency [17].

Key points

- Frailty is a pathophysiological vicious cycle based on chronic undernutrition and loss of muscle mass, leading to disability and care dependency if the cycle is not interrupted.

- There is practically no evidence on when and how to treat hypertension in frail patients. Further research is needed.

- Therefore, current recommendations for target blood pressure depend rather on tolerability of antihypertensive drugs, remaining life span and concomitant chronic diseases than on frailty per se.

Disclosure statement

References

- Fried, L.P.; Tangen, C.M.; Walston, J.; Newman, A.B.; Hirsch, C.; Gottdiener, J.; et al. Cardiovascular Health Study Collaborative Research Group. Frailty in older adults: evidence for a phenotype. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2001, 56, M146–M156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vetrano, D.L.; Palmer, K.M.; Galluzzo, L.; Giampaoli, S.; Marengoni, A.; Bernabei, R.; et al. Joint Action ADVANTAGE WP4 group. Hypertension and frailty: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open. 2018, 8, e024406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barzilay, J.I.; Blaum, C.; Moore, T.; Xue, Q.L.; Hirsch, C.H.; Walston, J.D.; et al. Insulin resistance and inflammation as precursors of frailty: the Cardiovascular Health Study. Arch Intern Med. 2007, 167, 635–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anker, D.; Santos-Eggimann, B.; Zwahlen, M.; Santschi, V.; Rodondi, N.; Wolfson, C.; et al. Blood pressure in relation to frailty in older adults: A population-based study. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich). 2019, 21, 1895–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ravindrarajah, R.; Hazra, N.C.; Hamada, S.; Charlton, J.; Jackson, S.H.; Dregan, A.; et al. Systolic Blood Pressure Trajectory, Frailty, and AllCause Mortality >80 Years of Age: Cohort Study Using Electronic Health Records. Circulation. 2017, 135, 2357–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tinetti, M.E.; Han, L.; Lee, D.S.; McAvay, G.J.; Peduzzi, P.; Gross, C.P.; et al. Antihypertensive medications and serious fall injuries in a nationally representative sample of older adults. JAMA Intern Med. 2014, 174, 588–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beckett, N.S.; Peters, R.; Fletcher, A.E.; Staessen, J.A.; Liu, L.; Dumitrascu, D.; et al. HYVET Study Group. Treatment of hypertension in patients 80 years of age or older. N Engl J Med. 2008, 358, 1887–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wright, J.T., Jr.; Williamson, J.D.; Whelton, P.K.; Snyder, J.K.; Sink, K.M.; Rocco, M.V.; Reboussin, D.M.; Rahman, M.; Oparil, S.; et al.; SPRINT Research Group A Randomized Trial of Intensive versus Standard Blood-Pressure Control. N Engl J Med. 2015, 373, 2103–16. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Warwick, J.; Falaschetti, E.; Rockwood, K.; Mitnitski, A.; Thijs, L.; Beckett, N.; et al. No evidence that frailty modifies the positive impact of antihypertensive treatment in very elderly people: an investigation of the impact of frailty upon treatment effect in the HYpertension in the Very Elderly Trial (HYVET) study, a double-blind, placebo-controlled study of antihypertensives in people with hypertension aged 80 and over. BMC Med. 2015, 13, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williamson, J.D.; Supiano, M.A.; Applegate, W.B.; Berlowitz, D.R.; Campbell, R.C.; Chertow, G.M.; et al. SPRINT Research Group. Intensive vs Standard Blood Pressure Control and Cardiovascular Disease Outcomes in Adults Aged ≥75 Years: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA. 2016, 315, 2673–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pajewski, N.M.; Williamson, J.D.; Applegate, W.B.; Berlowitz, D.R.; Bolin, L.P.; Chertow, G.M.; et al. SPRINT Study Research Group. Characterizing Frailty Status in the Systolic Blood Pressure Intervention Trial. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2016, 71, 649–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, B.; Mancia, G.; Spiering, W.; Agabiti Rosei, E.; Azizi, M.; Burnier, M.; et al. Authors/Task Force Members. 2018 ESC/ESH Guidelines for the management of arterial hypertension: The Task Force for the management of arterial hypertension of the European Society of Cardiology and the European Society of Hypertension: The Task Force for the management of arterial hypertension of the European Society of Cardiology and the European Society of Hypertension. J Hypertens. 2018, 36, 1953–2041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Onder, G.; Landi, F.; Fusco, D.; Corsonello, A.; Tosato, M.; Battaglia, M.; et al. Recommendations to prescribe in complex older adults: results of the CRIteria to assess appropriate Medication use among Elderly complex patients (CRIME) project. Drugs Aging. 2014, 31, 33–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Denardo, S.J.; Gong, Y.; Nichols, W.W.; Messerli, F.H.; Bavry, A.A.; Cooper-Dehoff, R.M.; et al. Blood pressure and outcomes in very old hypertensive coronary artery disease patients: an INVEST substudy. Am J Med. 2010, 123, 719–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Biaggioni, I. Orthostatic Hypotension in the Hypertensive Patient. Am J Hypertens. 2018, 31, 1255–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bertschi, D.; Moser, A.; Stortecky, S.; Zwahlen, M.; Windecker, S.; Carrel, T.; et al. Evolution of Basic Activities of Daily Living Function in Older Patients One Year after Transcatheter Aortic Valve Implantation. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2021, 69, 500–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bachmann, S.; Finger, C.; Huss, A.; Egger, M.; Stuck, A.E.; Clough-Gorr, K.M. Inpatient rehabilitation specifically designed for geriatric patients: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. BMJ 2010, 340, c1718, Edifix has not found an issue number in the journal reference. Please check the volume/issue information. (Ref. 17 “Bachmann, Finger, Huss, Egger, Stuck, Clough-Gorr, et al., 2010”). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

© 2021 by the author. Attribution Non-Commercial NoDerivatives 4.0.

Share and Cite

Schoenenberger, A.W. Hypertension in Frail Patients. Cardiovasc. Med. 2021, 24, 164. https://doi.org/10.4414/cvm.2021.02176

Schoenenberger AW. Hypertension in Frail Patients. Cardiovascular Medicine. 2021; 24(4):164. https://doi.org/10.4414/cvm.2021.02176

Chicago/Turabian StyleSchoenenberger, Andreas W. 2021. "Hypertension in Frail Patients" Cardiovascular Medicine 24, no. 4: 164. https://doi.org/10.4414/cvm.2021.02176

APA StyleSchoenenberger, A. W. (2021). Hypertension in Frail Patients. Cardiovascular Medicine, 24(4), 164. https://doi.org/10.4414/cvm.2021.02176