Abstract

We present a challenging case of myocardial infarction with partial intermittent obstruction of the left main coronary due to a mass of unknown origin in an otherwise healthy 34-year-old male.

Case report

A 34-year-old current smoker male was transferred to our coronary catheter laboratory for suspected myocardial infarction (Figure 1). He received a loading dose of 250 mg of aspirin, 60 mg of prasugrel and 5000 IU of unfractionated heparin during prehospital care. Coronary angiography revealed a mass partially protruding into the leh main coronary artery (LMCA) (Figure 2, movies 1–3).

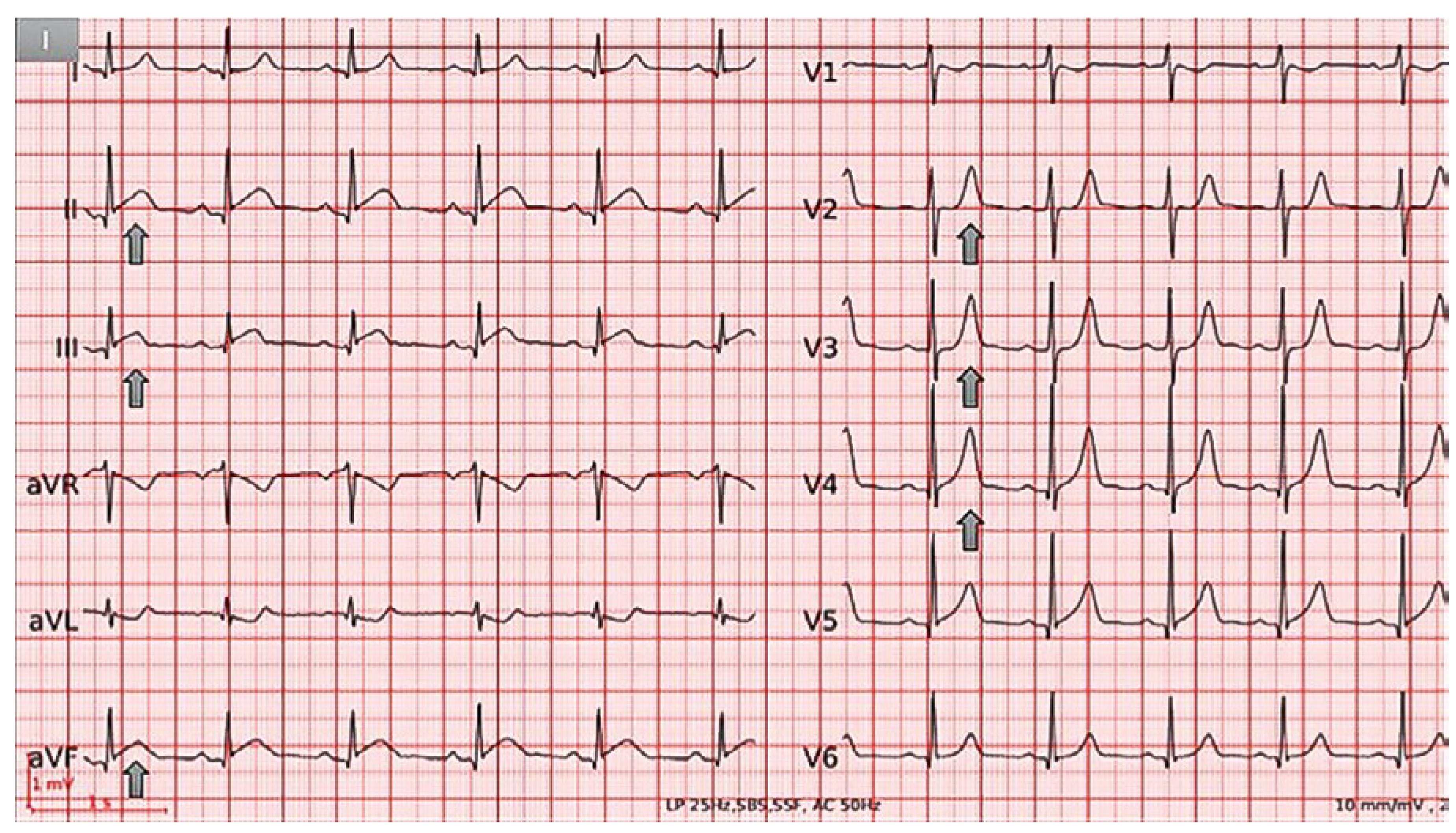

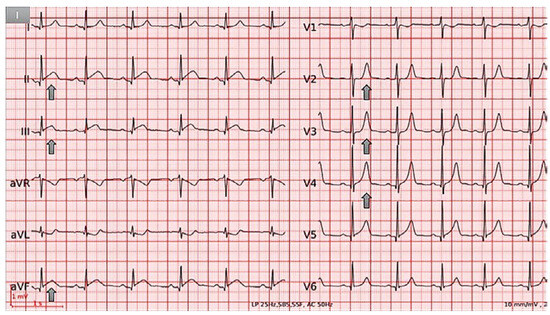

Figure 1.

ECG at admission demonstrating normal sinus rhythm,normal axis,mild ST-segment elevation and PR depression in II, III and aVF, and peakedT waves in V2−V4.

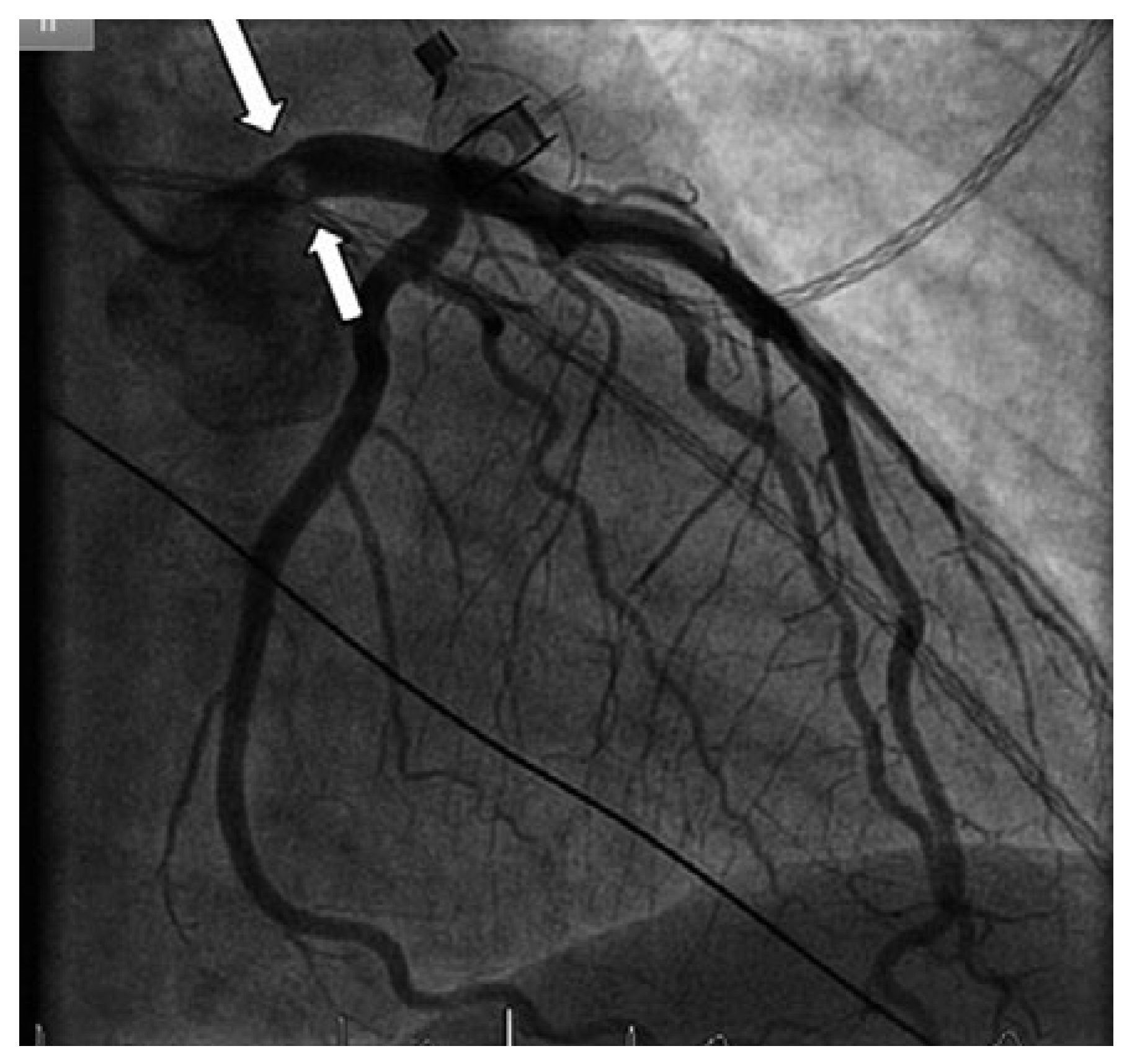

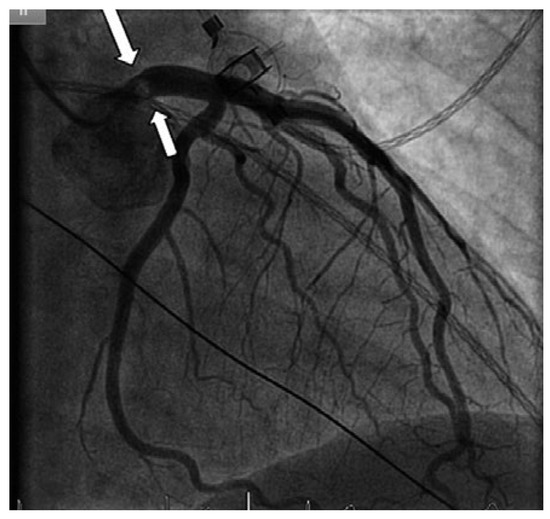

Figure 2.

Coronary angiogram showing a mass protruding partially into the left main coronary artery (arrow), but otherwise normal coronary arteries.

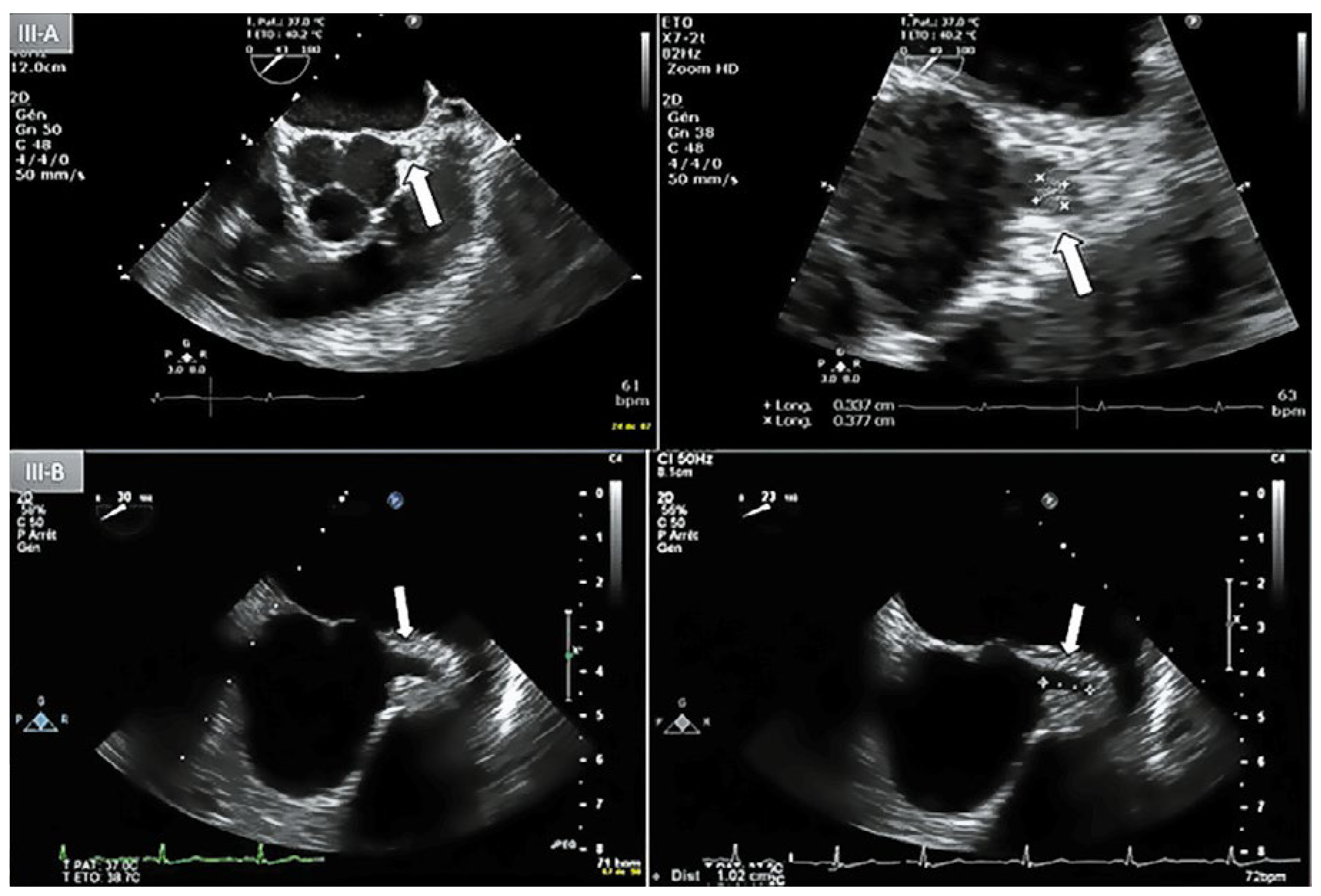

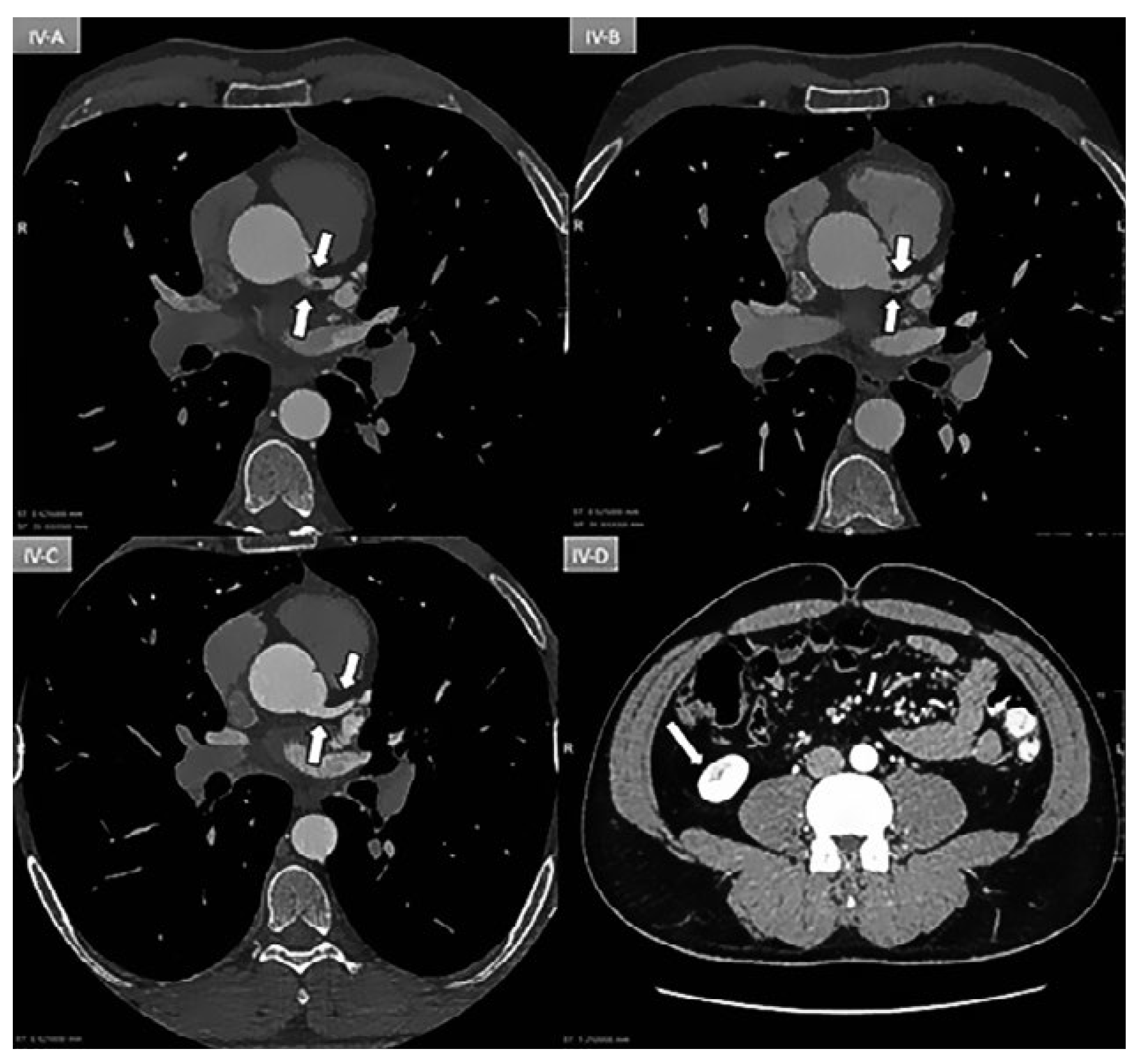

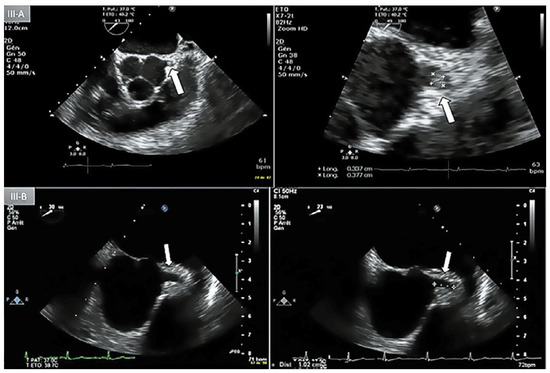

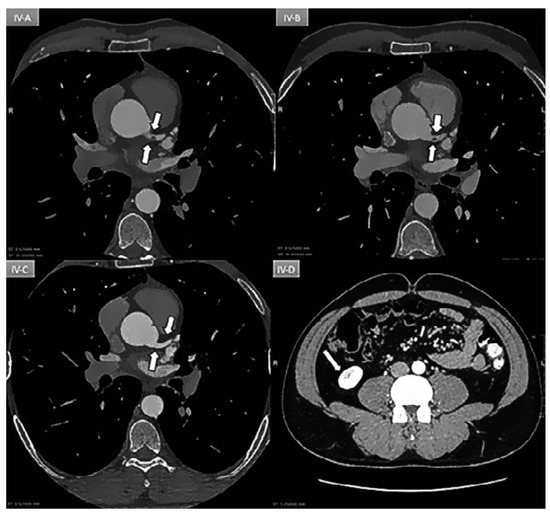

The coronary arteries were otherwise normal. Intravascular imaging was not performed because of the potential embolisation risk, and the patient was fully anticoagulated with heparin. Transthoracic and transoesophageal echocardiography (TTE and TEE) showed normal cavity dimensions, normal global and segmental systolic function, and normal valves. There was no intracardiac thrombus, no patent foramen ovale, nor any other shunts. A 3 × 3.5 mm mass was visualised in the LMCA (Figure 3A), and confirmed by coronary computed tomography (CT) (Figure 4A,B). The patient was clinically stable with no complaints, and the ECG was normal. The heart team strategy was to stop prasugrel, and proceed to surgical resection if the mass had remained unchanged aher anticoagulation or in the event of relapsing chest pain or haemodynamic instability. Repeat CT on day 3 showed a persistent mass, which had disappeared on TEE and CT on day 5 (figs 3B and 4C) but with a new triangular infarction of the lower pole of the right kidney (Figure 4D). Continuous monitoring over 5 days revealed no atrial flutter or fibrillation. We hypothesised that the mass had embolised peripherally. Further workup revealed no hypercoagulable state. Anticoagulation therapy was stopped and replaced with aspirin. At 1- and 6-month follow-up, the patient was asymptomatic with no mass on repeat TEE.

Figure 3.

A: Day-1 transoesophageal echocardiography (TEE) with short axis view showing an lntracoronary mass (3 x 3.5 mm) protruding lnto the lumen of the left main coronary artery (LMCA) (arrow). B: Day-5 repeat TEE, short axis view, absence of coronary mass in the proximal LMCA.

Figure 4.

A: Day 1: Coronary ECG-gating CT scan showing an intracoronary mass (arrow) partially occluding (70%) the lumen of the left main coronary artery. B: Day 3: Persistence of mass. C: Day 5: Patent vessel without any mass (arrow). D: Day-5: New triangular infarction of the lower pole of the right kidney consistent with peripheral embolisation.

Discussion

The mass protruding into the LMCA may have been a cardiac tumor, such as a papillary fibroelastoma (PFE). Whether the mass was an embolisation of a PFE from the aortic wall [1] or valve, or whether it originated from the LMCA is unclear as case reports have described PFEs in vascular lumens [2]. The main differential diagnosis remains a thrombus from either a ruptured plaque or from the leh heart cavities. However, normal TEE (dimensions, function, leh atrial appendage) and coronary arteries make this less likely. The systemic embolisation of the mass makes a tumour in the aortic valve region more probable than a thrombus, which would be expected to migrate down the coronary arteries. Intravascular imagery would have been very useful, but there have been cases of mass dislodgment during catheter manipulation leading to life-threatening events [3], which is why we opted for a conservative approach.

The management of myocardial infarction due to a nonobstructive LMCA mass depends on the underlying cause. The evidence is limited to two small case series from which no firm conclusions can be drawn [4,5]. Options include bypass surgery [6] or an initial conservative approach with anticoagulation. If PFE is suspected, patients should be anticoagulated to prevent further thrombotic embolisation, and early surgery should be considered [7,8] unless systemic embolisation of the entire mass occurs, as described in this case. In haemodynamically stable patients, a “watch and wait” approach may be appropriate, with repeat TTE during follow up as PFE recurrence is frequent. Elective surgery should be offered if the mass persists despite anticoagulation therapy. Unstable patients with coronary obstruction require first-line surgery. Primary percutaneous coronary intervention may be appropriate in highly unstable patients, depending on cardiac surgery availability, bearing in mind the risk of mass dislodgment, and/or distal embolisation [9].

Disclosure statement

No financial support and no other potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

References

- Yerebakan, C.; Liebold, A.; Steinhoff, G.; Skrabal, C.A. Papillary fibroelastoma of the aortic wall with partial occlusion of the right coronary ostium. Ann Thorac Surg. 2009, 87, 1953–1954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rolf, T.; Iglesias, J.F.; Tozzi, P.; von Segesser, L.K. Acute myocardial infarction caused by coronary embolization of a papillary fibroelastoma of the thoracic ascending aorta. Interact CardioVasc Thorac Surg. 2010, 11, 676–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gowda, R.M.; Khan, I.A.; Mehta, N.J.; Gowda, M.R.; Gropen, T.I.; Dogan, O.M.; et al. Cardiac papillary fibroelastoma originating from pulmonary veina case report. Angiology. 2002, 53, 745–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vander Salm, T.J. Unusual primary tumors of the heart. Semin Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2000, 12, 89–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, R.; Rahman, R.A.; Uretsky, B.F.; Schwarz, E.R. Leh main coronary artery thrombus: a case series with different outcomes. J Thromb Thrombolysis. 2005, 19, 125–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klein, A.J.; Casserly, I.P.; Messenger, J.C. Acute leh main coronary arterial thrombosis a case series. J Invasive Cardiol. 2008, 20, E243–E246. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Arora, N.P.; Jourmaa, M.; Rosman, H.; Mehta, R. Leh main coronary artery thrombosis with acute myocardial infarction: a management dilemma. Am J Med Sci. 2017, 53, 597–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boodhwani, M.; Veinot, J.P.; Hendry, P.J. Surgical approach to cardiac papillary fibroelastomas. Can J Cardiol. 2007, 23, 301–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, J.; Sethi, S.; Ahmed, H.; Pradad, A. Myocardial infarction secondary to inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor obstruction of the leh main: treated with primary PCI. Res Cardiovasc Med. 2016, 5, e32619. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

© 2018 by the author. Attribution - Non-Commercial - NoDerivatives 4.0.