LCZ696—a Promising New Compound in Heart Failure Treatment

Abstract

Current treatment of heart failure with reduced ejection fraction

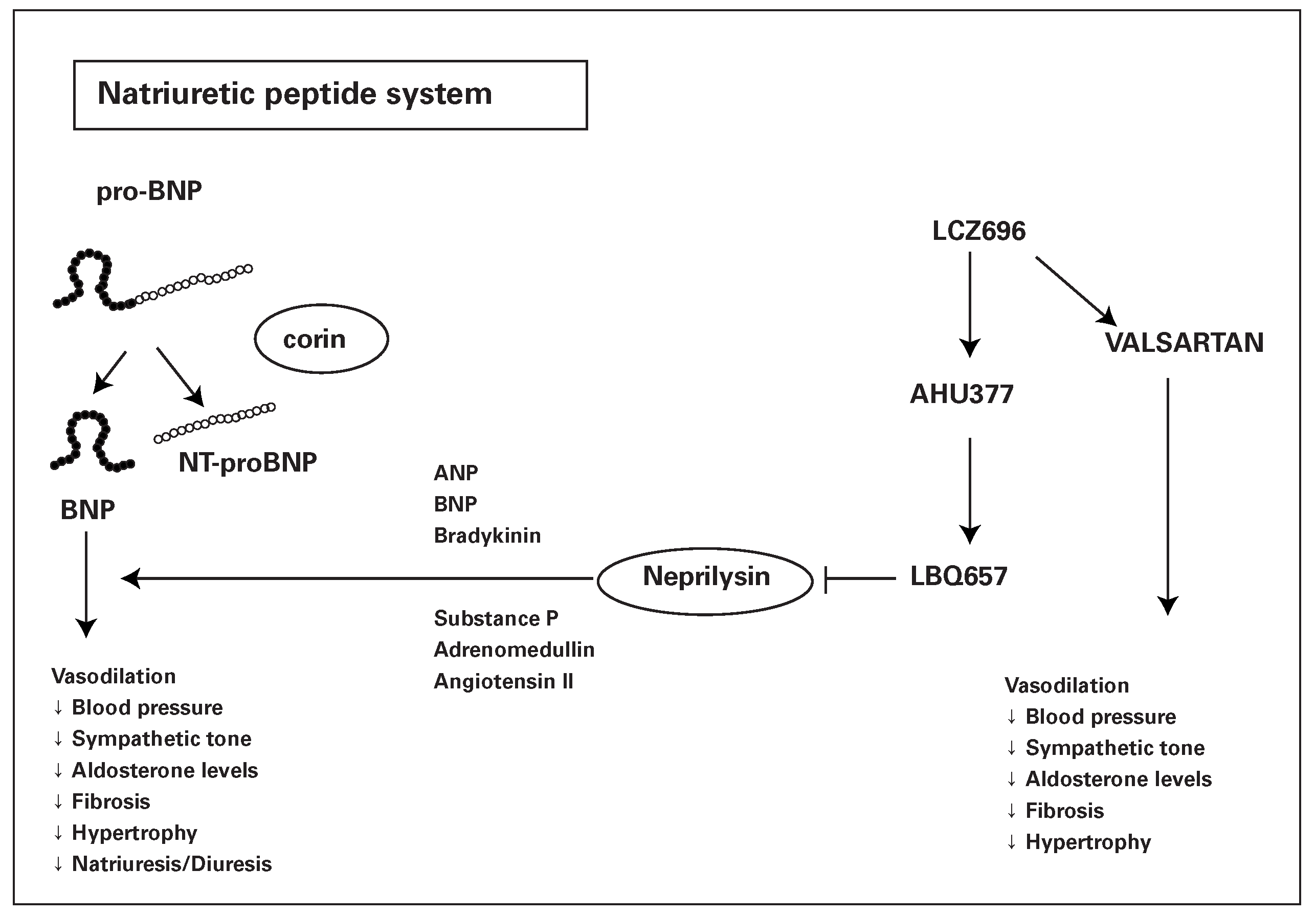

Natriuretic peptides and the reninangiotensin system

Clinical studies with LCZ696

Mild to moderate arterial hypertension

PARAMOUNT

PARADIGM-HF

Future role of LCZ696

Conclusion

Disclosures

References

- Cohn, J.N.; Archibald, D.G.; Ziesche, S.; Franciosa, J.A.; Harston, W.E.; Tristani, F.E.; et al. Effect of vasodilator therapy on mortality in congestive heart failure. Results of a veterans administration cooperative study. N Engl J Med. 1986, 314, 1547–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- The CONSENSUS Trial Study Group. Effects of enalapril on mortality in severe congestive HF: results of the Cooperative North Scandinavian Enalapril Survival Study (CONSENSUS). N Engl J Med. 1987, 316, 1429–35. [Google Scholar]

- The SOLVDInvestigators Effect of enalapril on survival in patients with reduced left ventricular ejection fractions congestive, HF. N Engl J Med. 1991, 325, 293–302. [CrossRef]

- McMurray, J.J.; Adamopoulos, S.; Anker, S.D.; Auricchio, A.; Boehm, M.; Dickstein, K.; et al. The Task Force for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Acute and Chronic HF 2012 of the European Society of Cardiology. Developed in collaboration with the HF Association (HFA) of the ESC. Eur Heart J. 2012, 33, 1787–1847. [Google Scholar]

- Maggioni, A.P.; Anand, I.; Gottlieb, S.O.; Latini, R.; Tognoni, G.; Cohn, J.N. Effects of valsartan on morbidity and mortality in patients with HF not receiving angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2002, 40, 1414–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konstam, M.A.; Neaton, J.D.; Dickstein, K.; Drexler, H.; Komajda, M.; Martinez, F.A.; et al. Effects of highdose versus low-dose losartan on clinical outcomes in patients with HF (HEAAL study): a randomised, double-blind trial. Lancet. 2009, 74, 1840–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zannad, F.; McMurray, J.J.; Krum, H.; van Veldhuisen, D.J.; Swedberg, K.; Shi, H. for the EMPHASIS-HF Study Group. Eplerenone in Patients with Systolic Heart Failure and Mild Symptoms. N Engl J Med. 2011, 364, 11–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohn, J.N.; Tognoni, G. A randomized trial of the angiotensin-receptor blocker valsartan in heart failure. N Engl J Med. 2001, 5, 293–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMurray, J.J.; Ostergren, J.; Swedberg, K.; Granger, C.B.; Held, P.; Michelson, E.L.; CHARM Investigators and Committees. Effects of candesartan in patients with chronic heart failure and reduced left-ventricular systolic function taking angiotensin-converting-enzyme inhibitors: the CHARM-Added trial. Lancet. 2003 Sep 6, 362, 767–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Cardiac Insufficiency Bisoprolol Study II (CIBIS-II): a randomized trial. Lancet. 1999, 353, 9–13. [CrossRef]

- Packer, M.; Coats, A.J.; Fowler, M.B.; Katus, H.A.; Krum, H.; Mohacsi, P.; et al. Effect of carvedilol on survival in severe chronic HF. N Engl J Med. 2001, 344, 1651–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Effect of metoprolol CR/XL in chronic HF: Metoprolol CR/XL Randomised Intervention Trial in Congestive HF (MERIT-HF). Lancet. 1999, 353, 2001–7. [CrossRef]

- Hjalmarson, A.; Goldstein, S.; Fagerberg, B.; Wedel, H.; Waagstein, F.; Kjekshus, J.; et al. Effects of controlled-release metoprolol on total mortality, hospitalizations, and wellbeing in patients with HF: the Metoprolol CR/XL Randomized Intervention Trial in congestive HF (MERITHF). MERIT-HF Study Group. JAMA 2000, 283, 1295–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rademaker, M.T.; Charles, C.J.; Espiner, E.A.; Nicholls, M.G.; Richards, A.M.; Kosoglou, T. Combined neutral endopeptidase and angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibition in HF: role of natriuretic peptides and angiotensin II. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 1998, 31, 116–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trippodo, N.C.; Fox, M.; Monticello, T.M.; Panchal, B.C.; Asaad, M.M. Vasopeptidase inhibition with omapatrilat improves cardiac geometry and survival in cardiomyopathic hamsters more than does ACE inhibition with captopril. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 1999, 34, 782–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campese, V.M.; Lasseter, K.C.; Ferrario, C.M.; et al. Omapatrilat versus lisinopril: efficacy and neurohormonal profile in salt-sensitive hypertensive patients. Hypertension. 2001, 38, 1342–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rouleau, J.L.; Pfeffer, M.A.; Stewart, D.J.; et al. Comparison of vasopeptidase inhibitor, omapatrilat, and lisinopril on exercise tolerance and morbidity in patients with HF: IMPRESS randomised trial. Lancet. 2000, 356, 615–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Packer, M.; Califf, R.M.; Konstam, M.A.; Krum, H.; McMurray, J.J.; Rouleau, J.L.; et al. Comparison of omapatrilat and enalapril in patients with chronic HF: the Omapatrilat Versus Enalapril Randomized Trial of Utility in Reducing Events (OVERTURE). Circulation. 2002, 106, 920–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fryer, R.M.; Segreti, J.; Banfor, P.N.; Widomski, D.L.; Backes, B.J.; Lin, C.W.; et al. Effect of bradykinin metabolism inhibitors on evoked hypotension in rats: rank efficacy of enzymes associated with bradykinin-mediated angioedema. Br J Pharmacol. 2008, 153, 947–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruilope, L.M.; Dukat, A.; Böhm, M.; Lacourcière, Y.; Gong, J.; Lefkowitz, M.P. Blood-pressure reduction with LCZ696, a novel dual-acting inhibitor of the angiotensin II receptor and neprilysin: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, active comparator study. Lancet. 2010, 375, 1255–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solomon, S.D.; Zile, M.; Pieske, B.; Voors, A.; Shah, A.; KraigherKrainer, E.; et al. for the Prospective comparison of ARNI with ARB on Management of heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (PARAMOUNT) Investigators. Lancet. 2012, 380, 1387–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMurray, J.J.; Packer, M.; Desai, A.S.; Gong, J.; Lefkowitz, M.P.; Rizkala, A.R. for the PARADIGM-HF Investigators and Committees. Angiotensin–Neprilysin Inhibition versus Enalapril in Heart Failure. N Engl J Med. 2014 Sep 11, 371, 993–1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The ONTARGET investigators. Telmisartan, ramipril, or both in patients at high risk for cardiovascular events. N Engl J Med. 2008, 358, 1547–1559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maggioni, A.P.; Anker, S.D.; Dahlström, U.; Filippatos, G.; Ponikowski, P.; Zannad, F.; et al. Are hospitalized or ambulatory patients with HF treated in accordance with European Society of Cardiology guidelines? Evidence from 12,440 patients of the ESC HF Long-Term Registry. Eur J Heart Fail. 2013, 15, 1173–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Colucci, W.S.; Elkayam, U.; Horton, D.P.; Abraham, W.T.; Bourge, R.C.; Johnson, A.D.; et al. intravenous nesiritide, a natriuretic peptide, in the treatment of decompensated congestive heart failure. N Engl J Heart Fail. 2000, 343, 246–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garg, R.; Yusuf, S. ; for the Collaborative group on ACEinhibitor trials Overview of randomized trials on angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors on mortality morbidity in patients with heart failure. JAMA 1995, 273, 1450–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| ONTARGET | ONTARGET | PARADIGM-HF | PARADIGM-HF | |

| Ramipril | Telmisartan | LCZ696 | Enalapril | |

| (n = 8,576) | (n = 8,542) | (n = 4,187) | (n = 4,212) | |

| Variable | ||||

| Discontinuation (n, %) | 2,099 (24.5%) | 1,962 (23%) | 977 (23.3%) | 1,094 (26%) |

| Hypotension (n, %) | 149 (1.7%) | 229 (2.7%) | 700 (16.7%) | 447 (10.6%) |

| Cough (n, %) | 360 (4.2%) | 93 (1.1%) | 474 (11.3%) | 601 (14.3%) |

| Angioedema (n, %) | 25 (0.3%) | 10 (0.1%) | 19 (0.4%) | 10 (0.3%) |

| Hyperkalaemia (n, %) | 283 (3.2%) | 287 (3.4%) | 855 (20.4%) | 960 (22.9%) |

© 2015 by the author. Attribution - Non-Commercial - NoDerivatives 4.0.

Share and Cite

Hullin, R. LCZ696—a Promising New Compound in Heart Failure Treatment. Cardiovasc. Med. 2015, 18, 173. https://doi.org/10.4414/cvm.2015.00330

Hullin R. LCZ696—a Promising New Compound in Heart Failure Treatment. Cardiovascular Medicine. 2015; 18(5):173. https://doi.org/10.4414/cvm.2015.00330

Chicago/Turabian StyleHullin, Roger. 2015. "LCZ696—a Promising New Compound in Heart Failure Treatment" Cardiovascular Medicine 18, no. 5: 173. https://doi.org/10.4414/cvm.2015.00330

APA StyleHullin, R. (2015). LCZ696—a Promising New Compound in Heart Failure Treatment. Cardiovascular Medicine, 18(5), 173. https://doi.org/10.4414/cvm.2015.00330