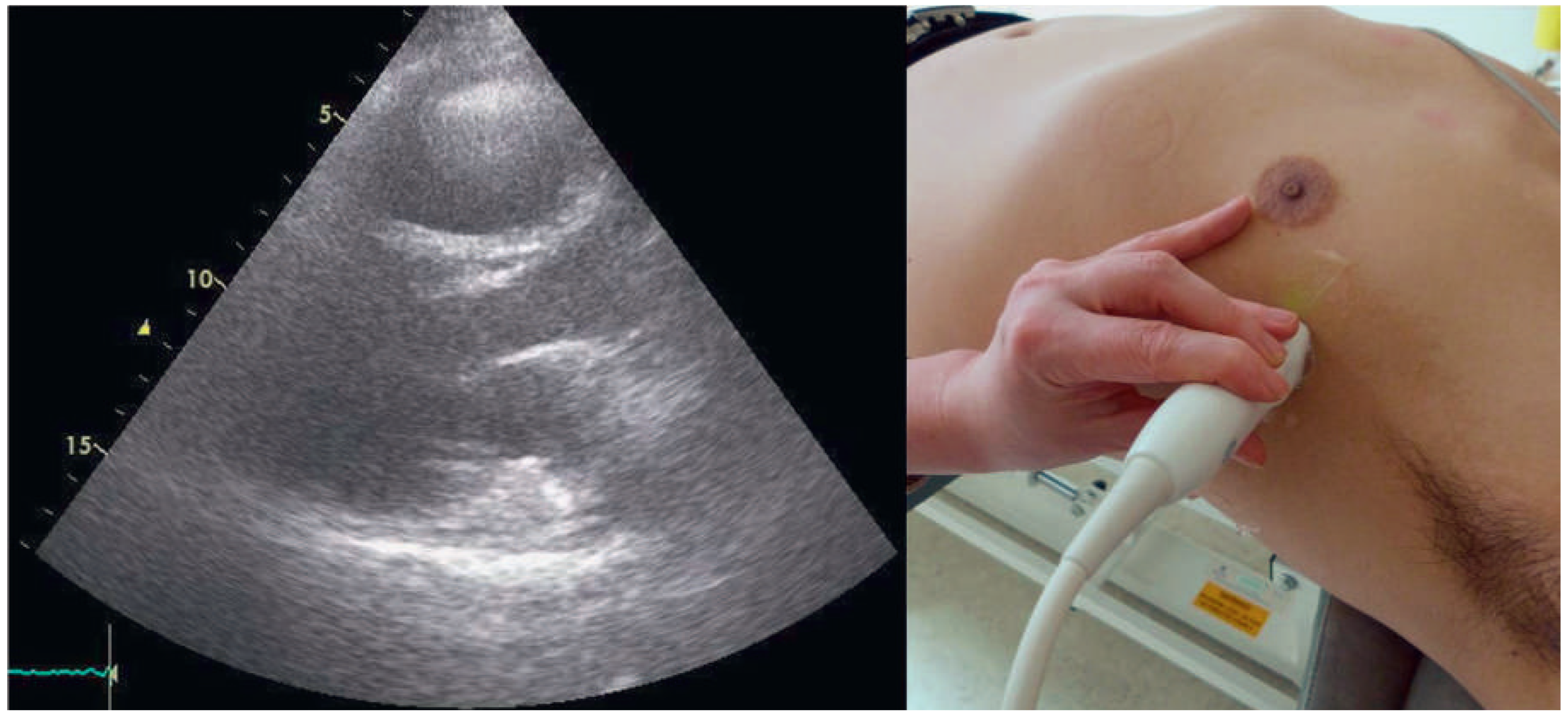

A 57-year-old male presented to the medical outpatient department with typical angina pectoris Canadian Cardiovascular Society (CCS) class II and dyspnoea on exertion during the previous weeks. Additionally he had retrosternal pain at rest and dyspnoea during the previous night. The patient had a a history of untreated arterial hypertension. On initial workup, the patient was in a stable cardiovascular condition with an office blood pressure of 150/88 mm Hg, and the cardiac examination was unremarkable. Blood tests revealed serially negative high-sensitivity troponins. Glycated haemoglobin was 6.4%, consistent with prediabetes, and lowdensity lipoprotein cholesterol was 2.5 mmol/l. An electrocardiogram (ECG) showed sinus rhythm, right axis deviation, signs of an incomplete right bundle-branch block with rR’ morphology in leads V1 to V4, and lateral displacement of the transition zone in the precordial leads, but no signs of acute ischaemia (

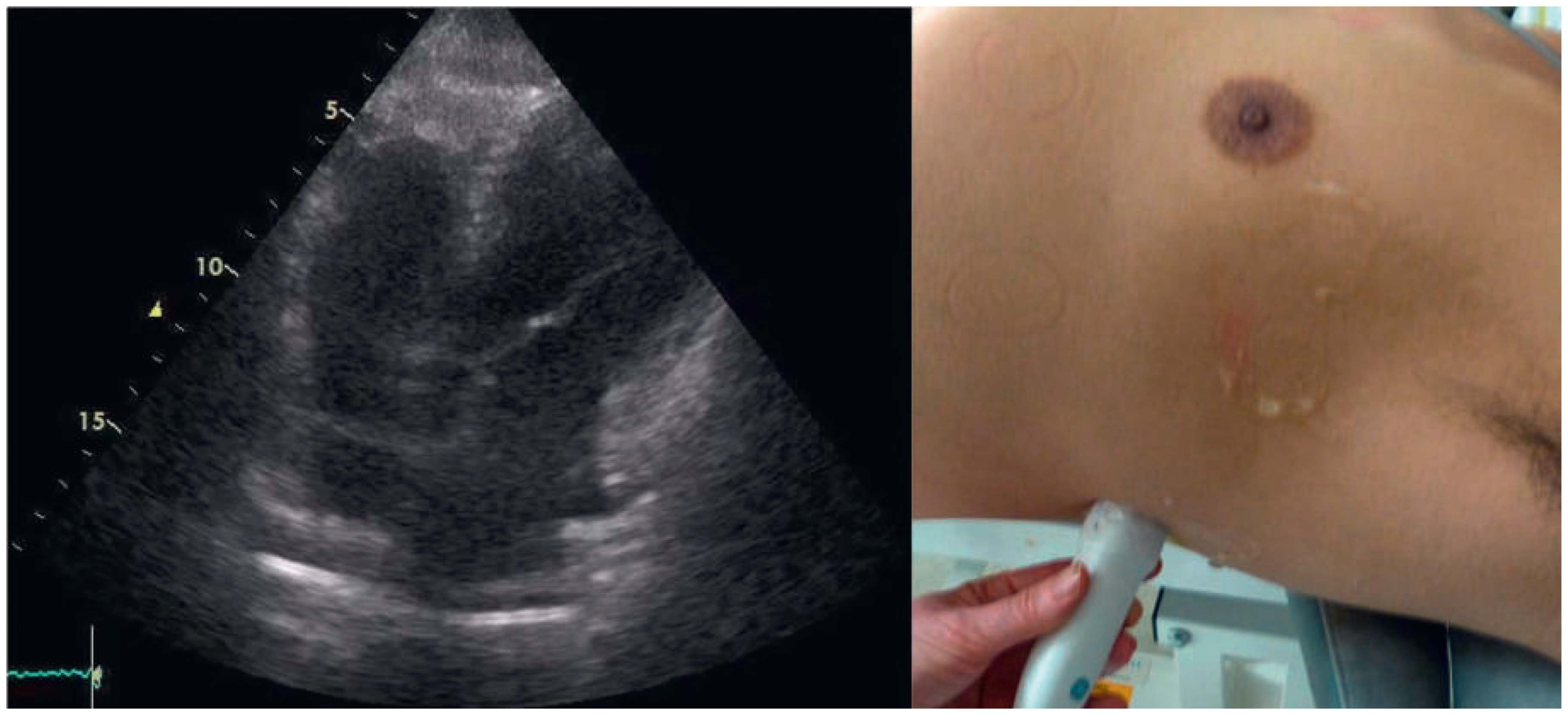

Figure 1). On echocardiography, the image acquisition was difficult with a typical long axis view acquired in the fifth intercostal space in the midaxillary line (

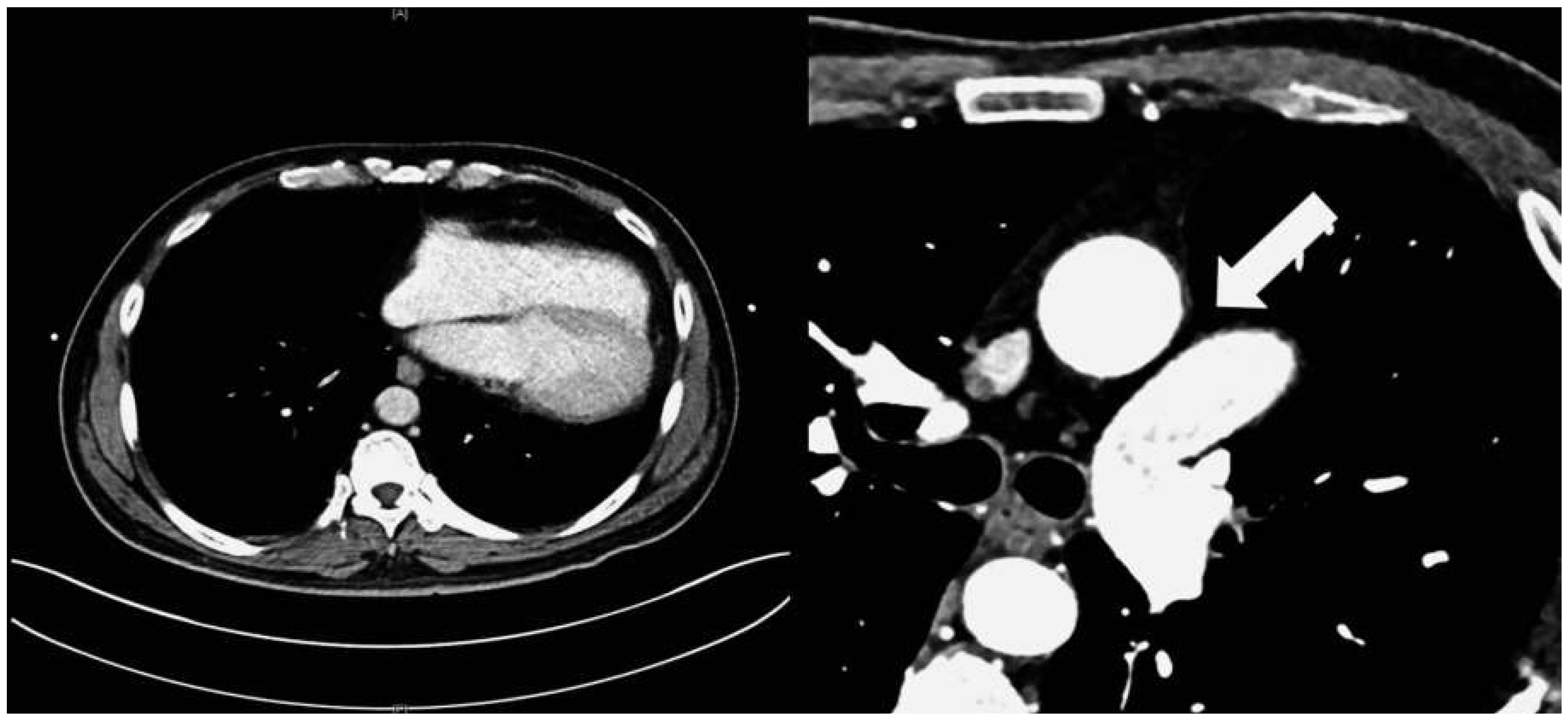

Figure 2) and apical views acquired from a posterolateral window (

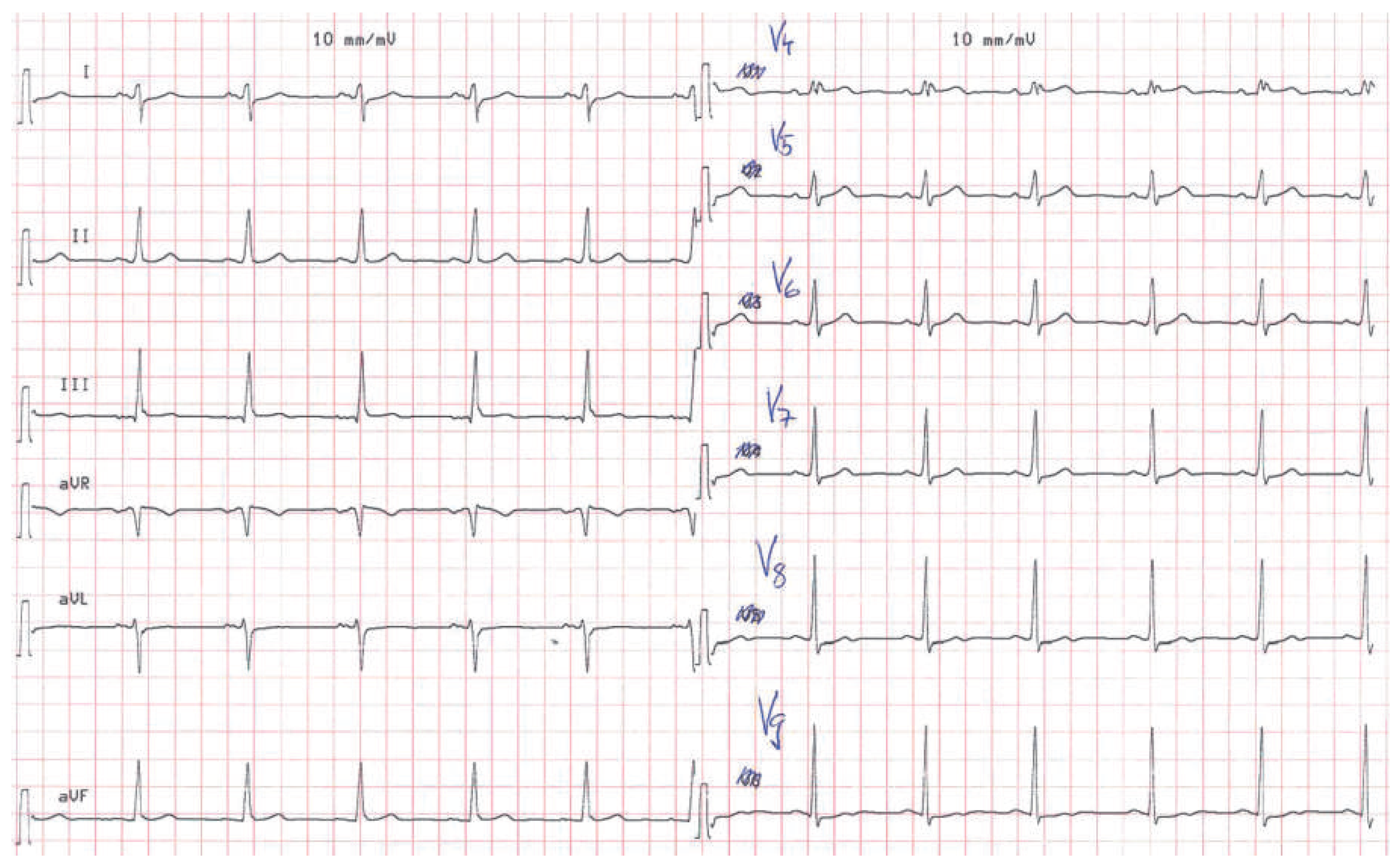

Figure 3). Computed tomography angiography (CTA) of the heart showed that the entire heart was displaced leftwards into the left hemithorax. Also evident was a lingula of lung tissue interposed between the aorta and the pulmonary artery indicating a congenitally absent pericardium (

Figure 4). Additionally, the CT scan revealed coronary artery disease with soft plaques and >70% stenoses of the left anterior descending artery (LAD), the left circumflex artery (50%–70% stenosis) and the first marginal branch (>70% stenosis). Considering the diagnosis of a congenitally absent pericardium, the ECG was repeated, with leads V7–V9, showing a normal R-progression from V4 to V9 (

Figure 5). Coronary angiography with primary stenting of a 95%–99% stenosis of the LAD artery and a 75%–95% stenosis of the first marginal branch resulted in complete resolution of symptoms.

Congenitally absent pericardium is a rare condition found in 1/10 000 autopsies with morphological patterns of: total bilateral absence (extremely rare); partial left absence (70%); and partial right absence (17%) [

1]. It may be associated with other congenital defects such as atrial septal defects, persistant ductus arteriosus, bicuspid aortic valve or tetralogy of Fallot [

2]. Most patients are asymptomatic but absent pericardium may cause paroxysmal, stabbing, nonexertional chest pain. In partial left absence severe complications may be caused by herniation of parts of the heart resulting in shortness of breath, syncope or sudden death [

1,

2]. On ECG, partial right bundle-branch block is common and displacement of the transition zone in the precordial leads is seen as a result of the displacement of the heart [

2]. On transthoracic echocardiography, the standard views are found to be displaced leftwards as is exemplified in

Figure 2. The diagnosis is usually established by use of CT or magnetic resonance tomography showing displacement of the heart into the left hemithorax and lung tissue interposed between the aorta and the main pulmonary artery [

2]. In symptomatic patients, and especially in patients with risk factors or symptoms of herniation, surgical therapy with pericardioplasty may be performed [

1,

2]. Our patient was symptom-free after coronary angiography and no treatment due to the congenitally absent pericardium was necessary.