SCAD usually occurs in the female population 8–9 times more often than in the male population. The mean age referred is between 35 and 46 years [

1]. Within the angiographies performed for acute coronary syndromes or stable angina, prevalence of SCAD varies from 0.2 to 1.1% [

1]. Nevertheless, women younger than 50 years old showing ST elevation acute coronary syndrome are believed to have an incidence of around 10% [

1]. Recurrent SCAD is even more rare. Because of limited clinical studies, the incidence of recurrent SCAD is difficult to estimate: in a retrospective cohort of 87 patients with SCAD, recurrence at forty-seven months occurred in 17%, mainly in previously unaffected coronary vessels despite risk factor management [

2]. Moreover, all the patients with recurrence were female and a connection between recurrence and noncoronary fibromuscular dysplasia (FMD) was described [

2]. SCAD is generally related to atherosclerosis or the peri-partum period. The pathogenesis is not fully understood. The rupture of atherosclerotic plaque or haemorrhage from weakened vasa vasorum may induce a dissection plane in the layers of the arterial wall. The blood collecting in the false lumen may lead to dilating haematoma and compression of the true lumen, resulting in restricted coronary blood flow, acute coronary syndrome or even sudden death [

2]. On the other hand, during pregnancy and early post-partum period, progesterone-induced weakening of vessel walls, hypercoagulability and elevated blood pressure with increased shear stress might lead to dissection [

3]. Moreover, intense emotional situations may generate coronary dissection [

1]. Many others entities have been linked to SCAD: excessive exercise, spasm and spastic agent (e.g., cocaine), connective tissue disorders (Marfan’s syndrome, type IV Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, systemic erythematous lupus) and vasculitis (polyarteritis nodosa, Kawasaki disease and eosinophilic arteritis) [

2]. The fibromuscular dysplasia, often in the setting of medial fibroplasia (80–90%), seems to play an important role in patients with non-atherosclerotic SCAD. Saw et al. found that most of these patients (86%) have FMD in at least one non-coronary territory (renal, iliac, cerebral) suggesting a link between an underlying coronary FMD and SCAD [

4]. Regarding the overall angiographic distribution of SCAD, a review of the literature shows LAD or multi-vessel involvement in the vast majority of the cases, RCA less frequently involved (predominantly in men) and LCx artery, left main stem and obtuse marginal seldom mentioned [

5]. SCAD presentation ranges from stable angina to acute myocardial infarction (STEMI/NSTEMI) with cardiogenic shock or sudden death [

5]. Tweet et al. found that 14% of their cohort experienced ventricular fibrillation or tachycardia requiring defibrillation [

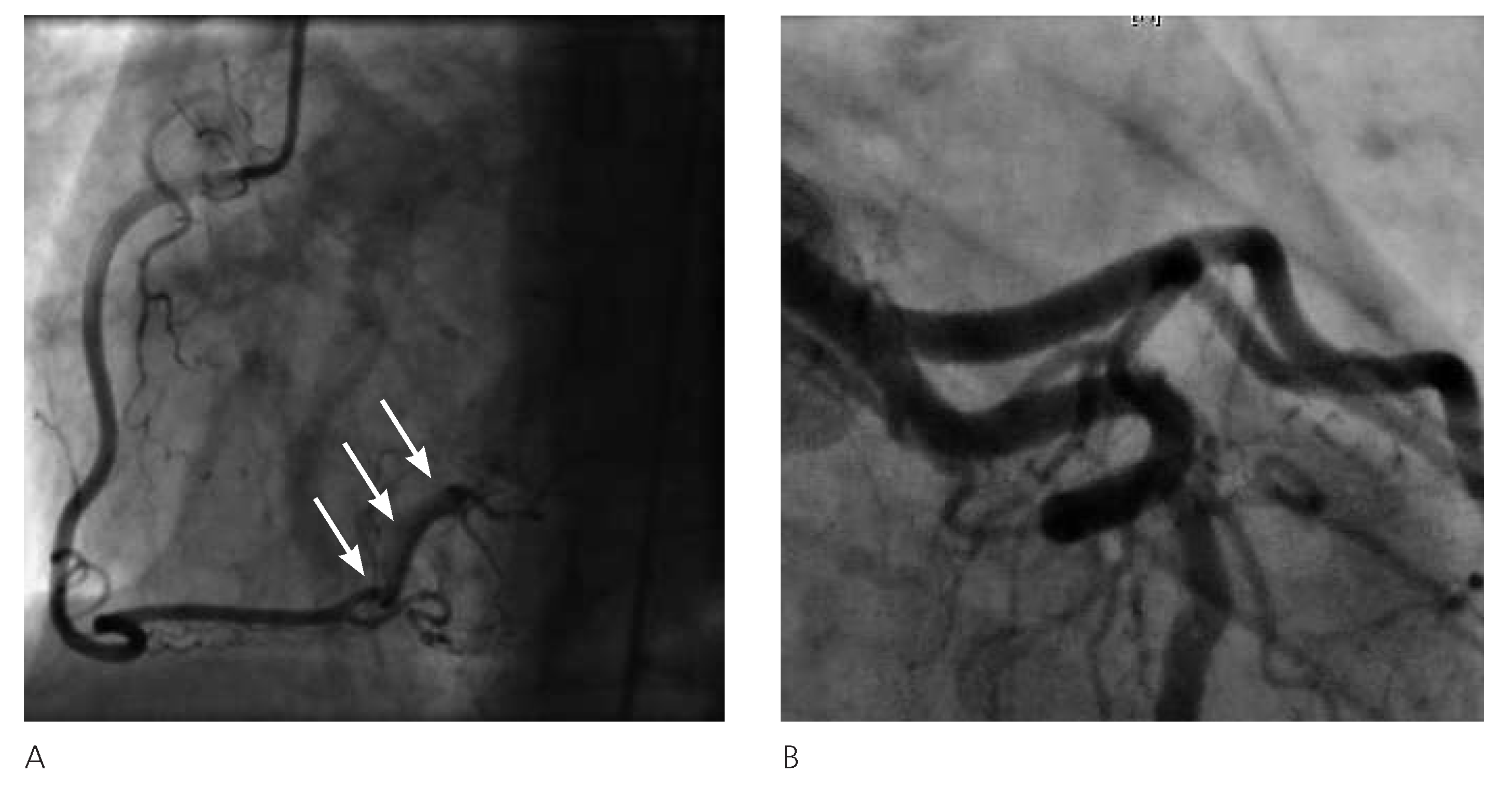

2]. The performed angiograms showed a subtotal stenosis of the vessel with narrowed aspect and a radiolucent defect suggestive of endothelial injury in the proximal segment of the lesion. In the literature, a thin radiolucent line representing the intimal flap as starting lesion is often described. Less frequently, coronary vessels appear narrowed or occluded because of a medial haematoma leading to compression of the true lumen [

6]. Recently, intravascular diagnostic techniques have allowed a better resolution of the vessel wall injuries, like the intimal flap, and the true and false lumen: the intravascular ultrasound can represent the extent of the disease even in large vessels, determining the aspect and size of the haematoma, and improving the precision of PCI. As a result of its high resolution, the optical computed tomography may describe the intimal tear and the inner layers of the media, providing information about the healing process of the coronary wall [

7]. The critical clinical presentation of the first episode, together with angiographic find ing of dissection in a major vessel with reduced flow (TIMI I), led us to a percutaneous coronary intervention and stent implantation. By contrast, the haemodynamic stability, regression of angina with nitrates and small size of the dissected vessel let us conservatively treat the patient three years later. Currently, no specific guideline exists about treatment in SCAD. Factors that may condition the treatment strategy include site of dissection, vessels involved and haemodynamic parameters [

5]. Conservative therapy seems appropriate in stable patients with mid- or distal SCAD, limited dissection at angiogram and normal flow in the affected artery [

1,

2]. It consists principally of beta-blocker and nitrates; antiplatelet (aspirin, clopidogrel, glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors) and anticoagulant (heparin) therapy are accepted to decrease thrombus formation in the false lumen even if the possibility of bleeding increase and propagation of dissection is reported [

2]. On the other hand, PCI is considered in a major vessel disease or ongoing ischaemia pattern but it may propagate the dissection or cause stent deployment into the false lumen with abolition of coronary flow [

2,

5]. Coronary artery bypass graft is generally reserved to left main stem or multivessel involvement [

5]. Despite the different presentations, the patient made a good recovery each time. Unexpectedly, the coronary angiography performed in 2010 showed almost complete healing of the previously dissected distal RCA and confirmed LCx patency. In our case, both invasive and conservative treatments, closely related to clinical presentation and angiographic findings, have shown to be effective options. The presentation of SCAD as acute coronary syndrome is related to an initial morbidity with a mean value of in-hospital mortality of around 3% [

1]; as a long-term outcome, Tweet et al. found in their cohort of patients a 1- and 10-year mortality rate of 1.1 and 7.7%, respectively, and a 10-year rate of major adverse cardiac events (MACE) of 47.4% [

2]. Alfonso et al. reported 45 consecutive patients with SCAD initially conservatively managed and with revascularisation restricted to those with ongoing ischaemia: at follow-up, the 3-year event-free survival was 92% [

7].