New Frontiers in Exercise Training and Testing †

Summary

New frontiers in exercise training and testing

- –

- New guidelines for Body Mass Index and percentbody-fat classifications.

- –

- New table explaining abnormal exercise test findings.

- –

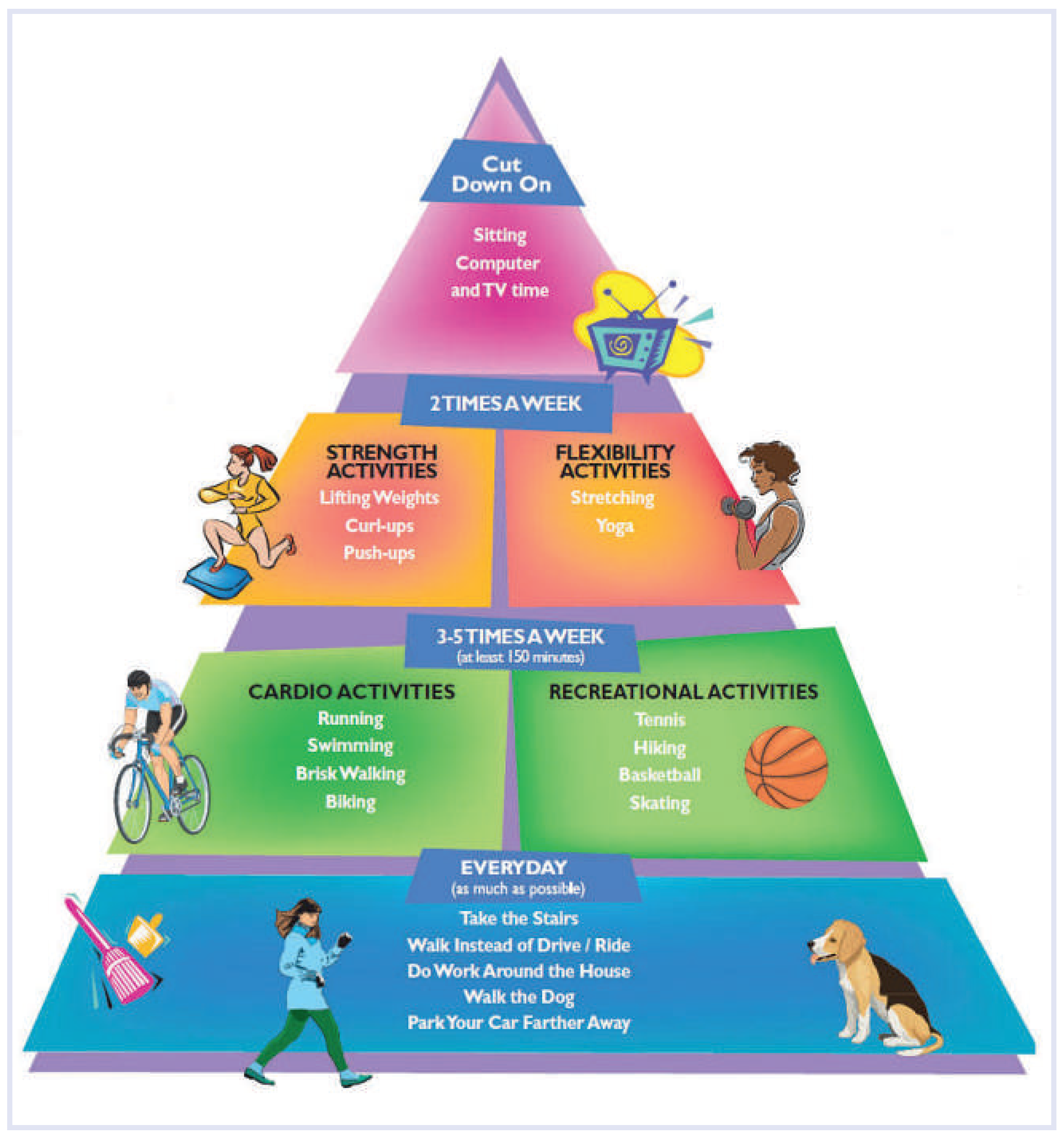

- Introduction of the “activity pyramid” as a general rule for exercise prescription, using a concept similar to the food pyramid in order to provide an easy method to advocate physical activity (Figure 1).

- –

- Greatly expanded section focusing on prescription guidelines for both the elderly and children, along with addressing the topic of increasing physical activity in schools and communities.

- –

- A new chapter on how to address ways to increase compliance and to decrease risk factors.

- –

- A new chapter on the use of informed consent, licensing, and proper supervision for exercise tests.

- –

- Pedometers, step-counting devices used to measure physical activity, are not an accurate measure of exercise quality and should not be used as the sole measure of physical activity.

- –

- Though exercise protects against heart disease, it is still possible for active adults to develop heart problems. All adults must be able to recognise the warning signs of heart disease, and all health care providers should ask patients about these symptoms.

- –

- Sedentary behaviour—sitting for long periods of time—is distinct from physical activity and has been shown to be a health risk in itself. Meeting the guidelines for physical activity does not make up for a sedentary lifestyle.

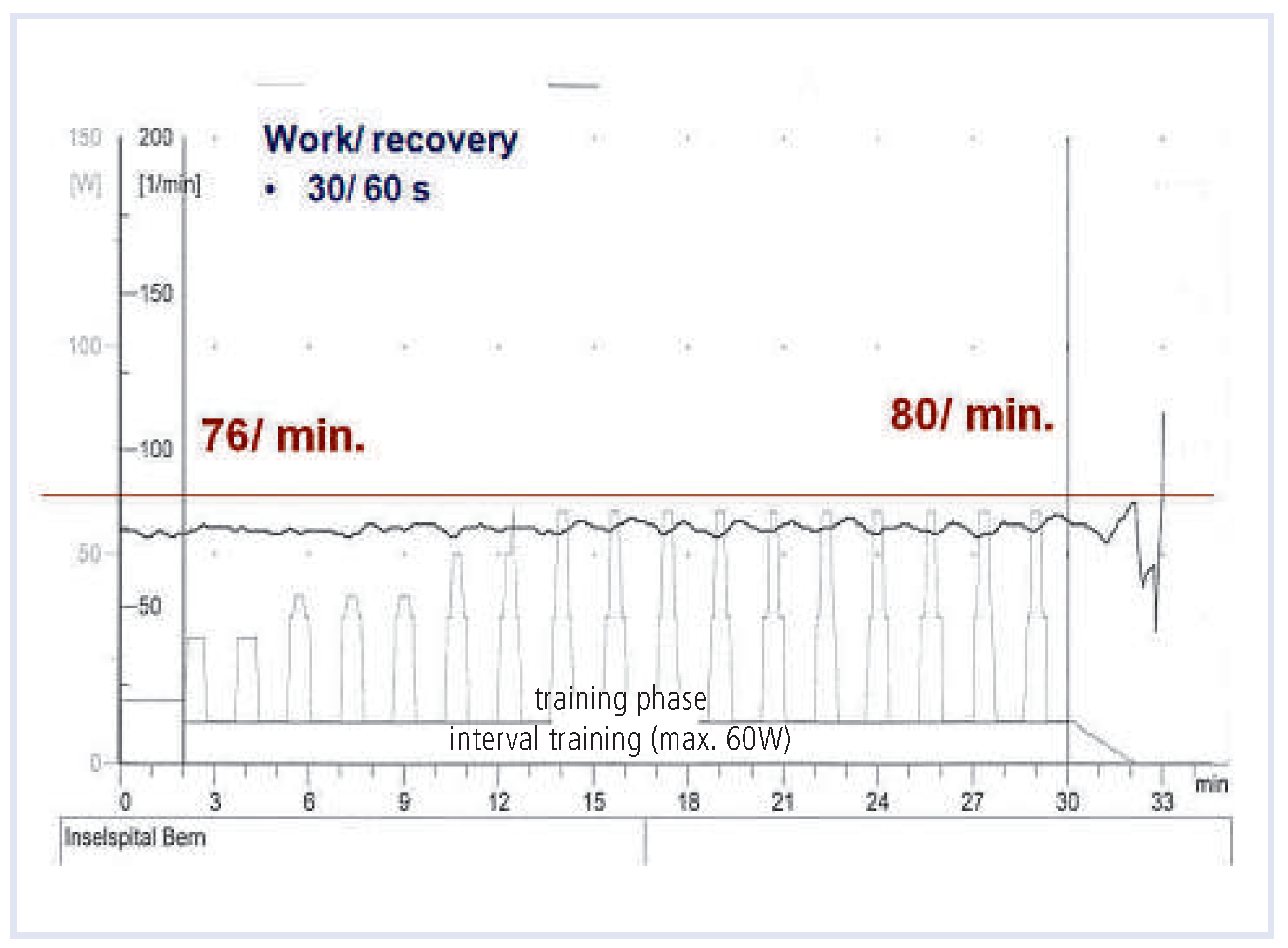

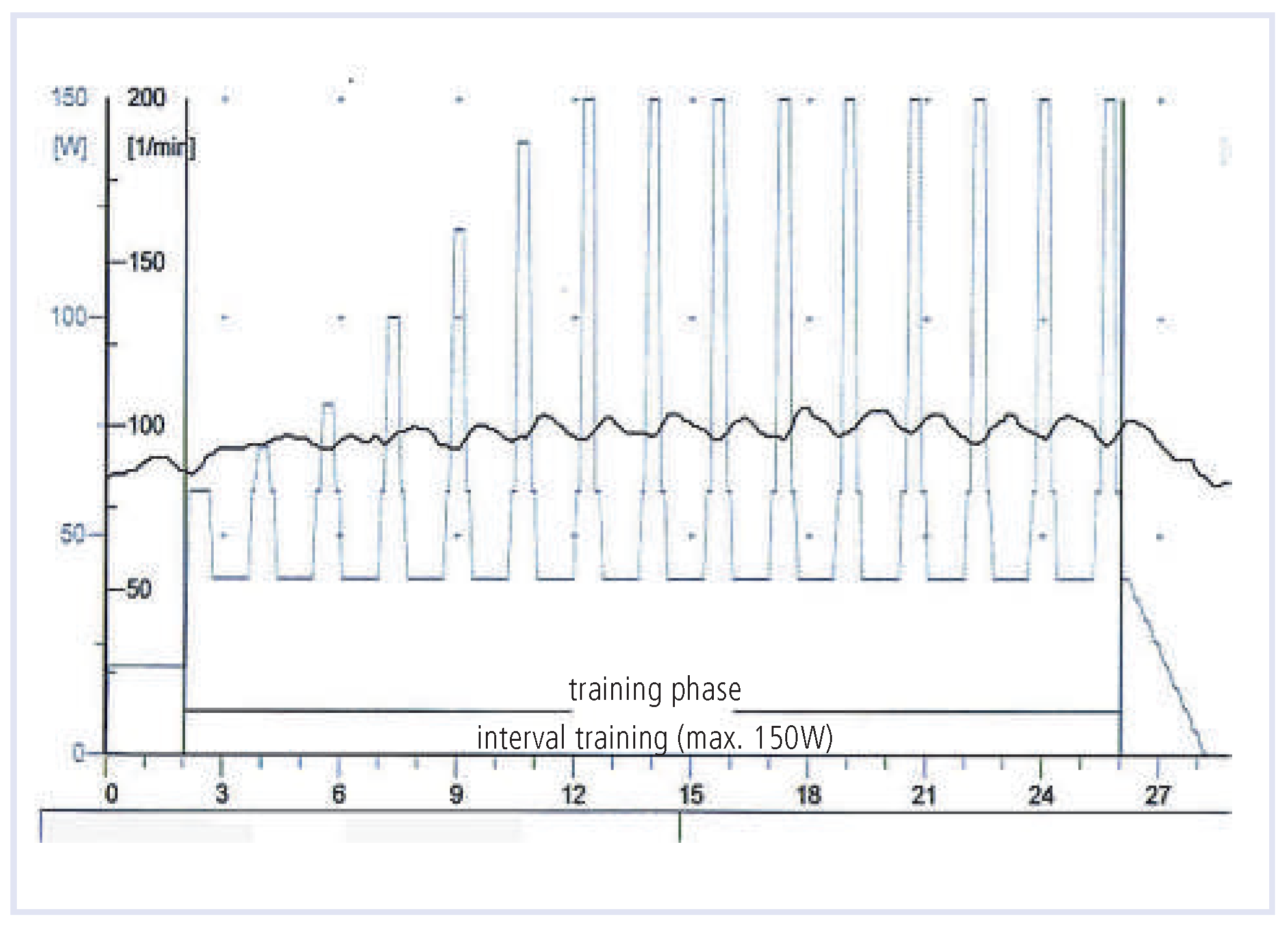

- High intensity interval training (bouts of 90 to 100% of heart rate reserve) vs. lower intensity, interspersed with rest (minimal threshold) for equal time periods.

- High-calorie-expenditure exercise to promote weight loss.

High intensity interval training

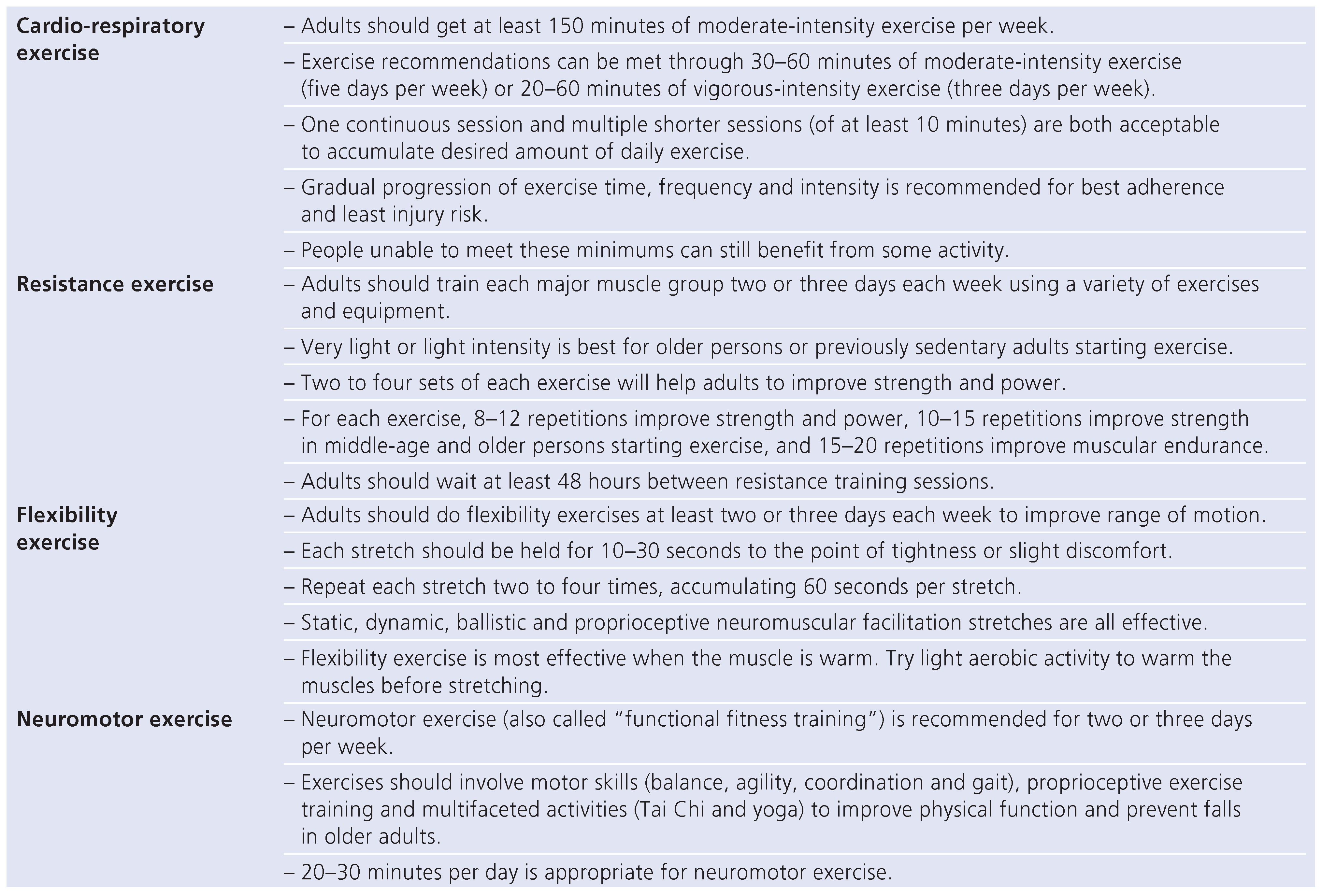

- Table 1: Recommendations for physical activity, categorised by cardio-respiratory exercise, resistance exercise, flexibility exercise and neuromotor exercise.

High-calorie-expenditure exercise

- –

- Exercise prescription for the high-calorie-expenditure should emphasise:

- –

- longer-duration (45 to 60 vs. 25 to 40 minutes per session)

- –

- lower-intensity (50% to 60% vs. 65% to 70% peak VO2)

- –

- more frequent (5 to 7 vs. 3 times a week) exercise

- –

- Walking should be the preferred exercise modality to maximise caloric expenditure vs. weight-supported exercises (cycling or rowing), which burn fewer calories.

- –

- The exercise expenditure goal of 3000 to 3500 kcal/week should be attained after 2 to 4 weeks of gradually lengthening the exercise bouts.

- –

- On-site sessions for at least two weeks can be useful for motivation and instruction, as well as home exercise logs (reviewed regularly with the exercise physiologist to estimate caloric expenditure and to ascertain compliance).

- –

- Individual or group counseling sessions emphasising dietary records, itemisation of food, and caloric content seem to be crucial in addition to regular physical activity.

- –

- Daily caloric goal should be set 500 kcal less than predicted maintenance calories.

- –

- Severely deconditioned patients are unable to follow a regular exercise training as proposed and need an individualised approach.

- –

- Patients with orthopaedic problems, which occur often in obese patients, especially in the elderly, should be offered alternative exercise modalities like stepper, crosstrainer or aqua-jogging.

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- ACSM’s Guidelines for Exercise Testing and Prescription, 8th ed.; Thompson, W.R., et al., Eds.; Lippinkott Williams & Wilkins: Baltimore, MD, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Garber, C.E.; et al. Quantity and quality of exercise for developing and maintaining cardiorespiratory, musculoskeletal, and neuromotor fitness in apparently healthy adults: guidance for prescribing exercise. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2011, 41, 334–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kemi, O.J.; et al. Moderate vs. high exercise intensity: differential effects on aerobic fitness, cardiomyocyte contractility, and endothelial function. Cardiovasc Res. 2005, 67, 161–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wisloff, U.; et al. Superior cardiovascular effect of aerobic interval training versus moderate continuous training in heart failure patients: a randomized study. Circulation. 2007, 115, 3086–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ades, P.A.; et al. High-calorie-expenditure exercise: a new approach to cardiac rehabilitation for overweight coronary patients. Circulation. 2009, 119, 2671–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

© 2011 by the author. Attribution - Non-Commercial - NoDerivatives 4.0.

Share and Cite

Schmid, J.-P. New Frontiers in Exercise Training and Testing. Cardiovasc. Med. 2011, 14, 299. https://doi.org/10.4414/cvm.2011.01622

Schmid J-P. New Frontiers in Exercise Training and Testing. Cardiovascular Medicine. 2011; 14(11):299. https://doi.org/10.4414/cvm.2011.01622

Chicago/Turabian StyleSchmid, Jean-Paul. 2011. "New Frontiers in Exercise Training and Testing" Cardiovascular Medicine 14, no. 11: 299. https://doi.org/10.4414/cvm.2011.01622

APA StyleSchmid, J.-P. (2011). New Frontiers in Exercise Training and Testing. Cardiovascular Medicine, 14(11), 299. https://doi.org/10.4414/cvm.2011.01622