Zusammenfassung

Vorhofflimmern führt durch unkoordinierte und schnelle elektrische Aktivierung der Vorhöfe zu frustranen Vorhofkontraktionen und somit zum Stillstand der Vorhofwände; in Verbindung mit der hieraus resultierenden Blutstase im linken Vorhof entstehen beste Voraussetzungen für die Bildung atrialer Thromben, welche in der Folge zu systemischen Thromboembolien führen können. Bei Patienten mit Vorhofflimmern stellen Herzinsuffizienz, Bluthochdruck, Diabetes mellitus, hohes Alter und ein vorangegangener Schlaganfall die Hauptrisikofaktoren für die Entwicklung eines Schlaganfalls dar, welche im CHADS2-Risiko-Score zusammengefasst werden. Um die optimale blutverdünnende Behandlungsstrategie bei diesen Patienten festzulegen, bedarf es einer individuell angepassten Risiko-Nutzen-Analyse. Für Patienten mit mittlerem bis hohem Schlaganfallrisiko bietet die orale Antikoagulation mit einem Ziel INR (International normalised ratio) 2,0–3,0 den besten Schutz vor einem Schlaganfall, während gleichzeitig das Risiko für schwere Blutungskomplikationen so gering wie möglich gehalten werden kann; Patienten mit niedrigem Schlaganfallrisiko hingegen scheinen am meisten von einer plättchenhemmenden Therapie mit Azetylsalizylsäure alleine zu profitieren. Wenn jedoch trotz bestmöglichem Einsatz von Seiten des Patienten und des behandelnden Arztes eine optimale INR-Kontrolle nicht erreicht werden kann, scheint auch bei den ersten beiden Patientengruppen durch eine blutverdünnende Therapie mit oraler Antikoagulation kaum ein zusätzlicher Benefit im Vergleich zu einer alleinigen plättchenhemmenden Therapie erreichbar zu sein. Diese Übersicht fasst die Strategien zur Risiko-Stratifizierung sowie Behandlungsoptionen von Patienten mit Vorhofflimmern zusammen, mit besonderem Augenmerk auf die Resultate der kürzlich publizierten ACTIVE-W (Atrial fibrillation Clopidogrel Trial with Irbesartan for prevention of Vascular Events)-Studie.

Schlüsselwörter: Vorhoffflimmern; Azetylsalizylsäure; orale Anticoagulation; CHADS-Score

Epidemiology and classification

Atrial Fibrillation (AF) is the most common cardiac arrhythmia with 4.5 million Europeans suffering from paroxysmal or persistent AF [

1]. An increase with age can be observed with only 0.4–1% of the general population as compared to 8% of people older than 80 years suffering from AF [

1,

2].

Patients with primary AF,

ie AF without a reversible cause such as acute myocardial infarction, cardiac surgery or hyperthyroidism, are classified according to the duration and relapse of AF. When first discovered, an episode of AF is referred to as

first-detected AF acknowledging the uncertainty with respect to duration and relapse of the arrhythmia whereas patients having experienced more than one documented episode of AF are considered to be suffering from

recurrent AF. Further subclassification is used with respect to the duration of the arrhythmia, separating

paroxysmal from

sustained AF with the first terminating spontaneously and the second persisting for more than seven days [

3].

Identifying patients at risk for stroke

In AF, uncoordinated and rapid activation of the left atrium results in futile contractions of the left atrium as well as left atrial wall stunning leading to reduced left ventricular filling and subsequently to a deterioration of left ventricular function. Severely reduced left atrial wall motion in conjunction with blood stasis in the left atrium, however, also favor local thrombus formation which consequently increase the risk of systemic thromboembolism. Among the possible thromboembolic complications encountered in AF, cerebral ischaemic events are primarily associated with the highest impact on patient survival and quality of life. Most strokes in AF patients result from thromboembolic disease from the left atrium; depending on the presence or absence of associated cardiovascular risk factors, the risk of patients with AF to experience a stroke ranges from 3–8% per year, increasing with age from 1.5% in the sixth as compared to 23.5% in the ninth decade of age [

4].

Hence, identification of patients at risk for the development of stroke is of pivotal interest. In data from the Atrial Fibrillation Investigators, pooled analyses of five randomised clinical trials identified prior stroke or TIA (transient ischaemic attack) as the most important independent risk factor for a subsequent stroke [

5]. Patients on acetylsalicylic acid with a history of prior stroke or TIA have a risk of subsequent stroke of 10–12% per year [

6]. Concomitant cardiovascular risk factors such as hypertension and diabetes mellitus as well as heart failure and age represent further important predictors of ischaemic stroke [

5,

7] as well as impaired left ventricular function as assessed by transthoracic echocardiography.

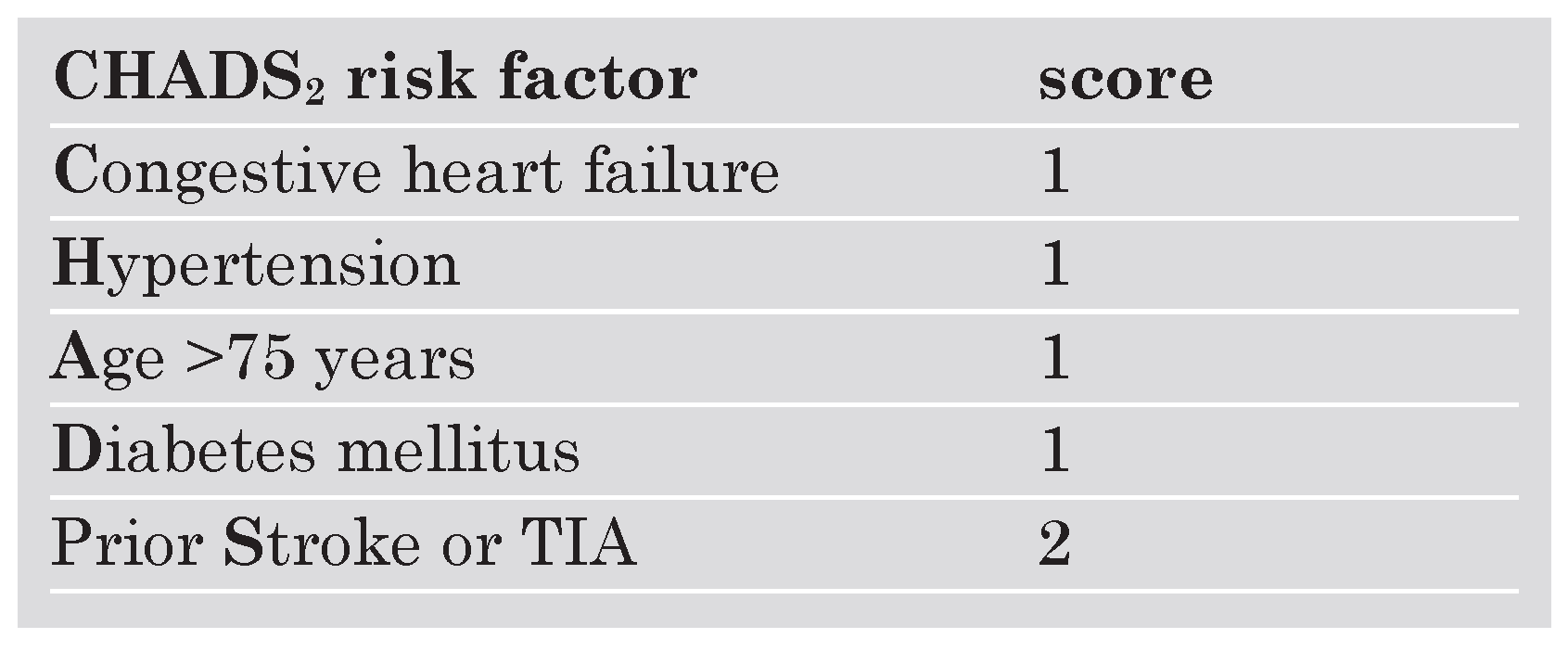

Several risk-assessment strategies were eventually combined and integrated into the CHADS

2 score providing a reliable and easyto-use scheme to identify AF patients at risk for stroke [

8,

9]. In the CHADS

2 scheme, 1 point is given for congestive heart failure (

C), hypertension (

H), age (

A), diabetes mellitus (

D) while 2 points are given for prior cerebral ischaemia (transient ischaemic attack or stroke [

S]) acknowledging the high predictive value of having experienced an ischaemic cerebral event for the development of a subsequent stroke (

Table 1) [

8].

Acetylsalicylic acid vs vitamin K antagonists

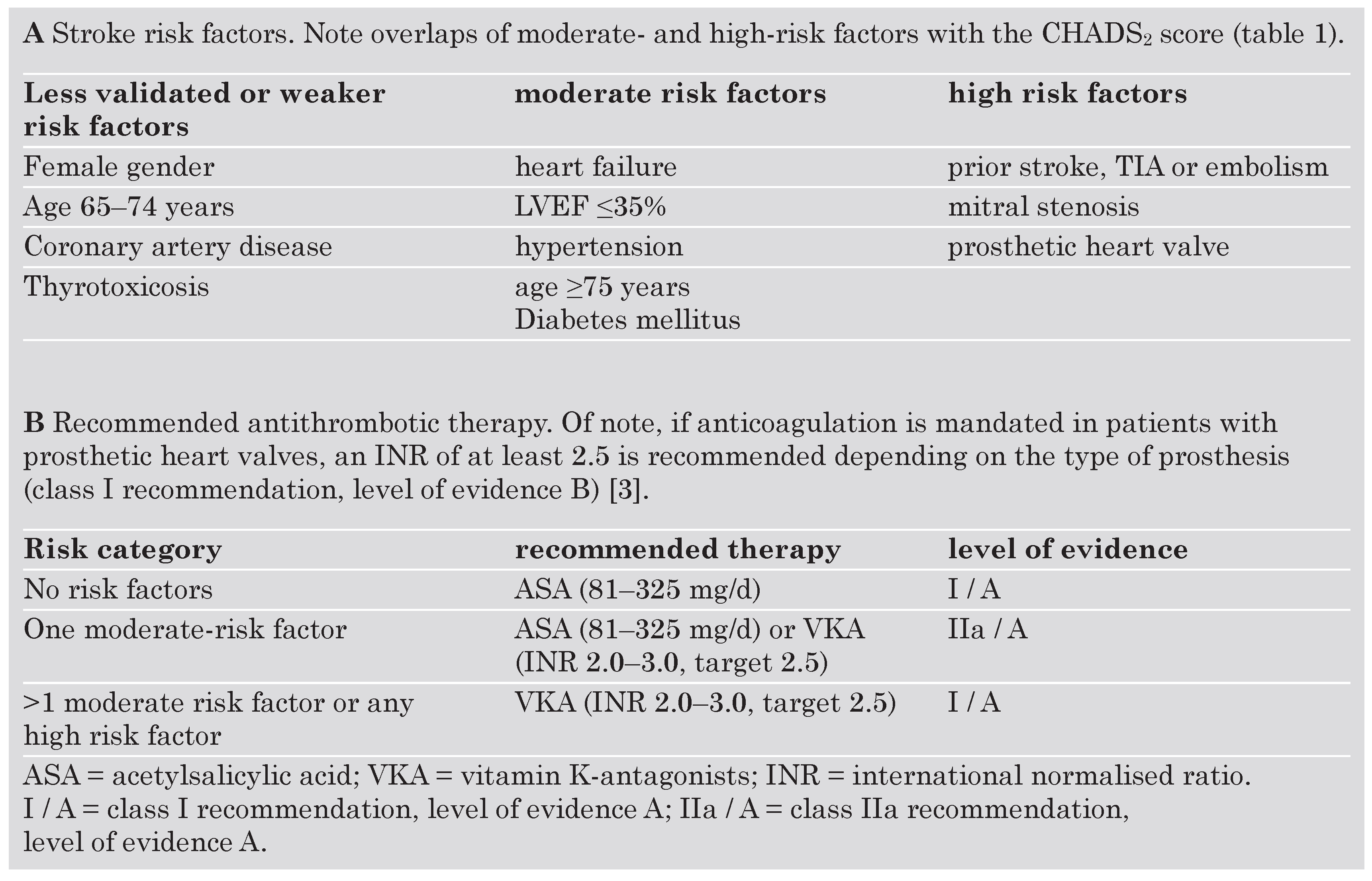

Based largely on the CHADS

2 index, the very recently updated ACC / AHA / ESC guidelines recommend antithrombotic therapy for patients with AF with either acetylsalicylic acid (ASA) or warfarin (

Table 2) [

3]. While class I recommendations are made based upon a general agreement that a given procedure is beneficial, useful and effective, conflicting evidence exists for class IIa recommendations with the weight of evidence / opinion in favor of the usefulness / efficacy [

3]. “Level A” recommendations are derived from the results of multiple randomised clinical trials, whereas “level B” evidence stems from the results of one randomised trial or from nonrandomised trials [

3].

Several large-scale randomised trials have investigated the efficacy of vitamin-K antagonists for stroke prevention in patients with AF. In a meta-analysis of the six largest such trials, oral anticoagulation (OAC) substantially reduced stroke risk by 61% in patients with AF [

10]. In these investigations, the benefit of antithrombotic therapy was not cropped by major bleeding complications; however, patients considered to be at high risk for bleeding were not included in these trials. Advanced age (in particular >85 years) as well as anticoagulation intensity (in particular an INR >3.5) are the most prominent risk predictors for bleeding [

11], with intracranial haemorrhage being the most important and potentially most devastating for the patient. As age >75 years constitutes both an increased risk for ischaemic cerebral events as well as an increased risk for intracranial bleeding [

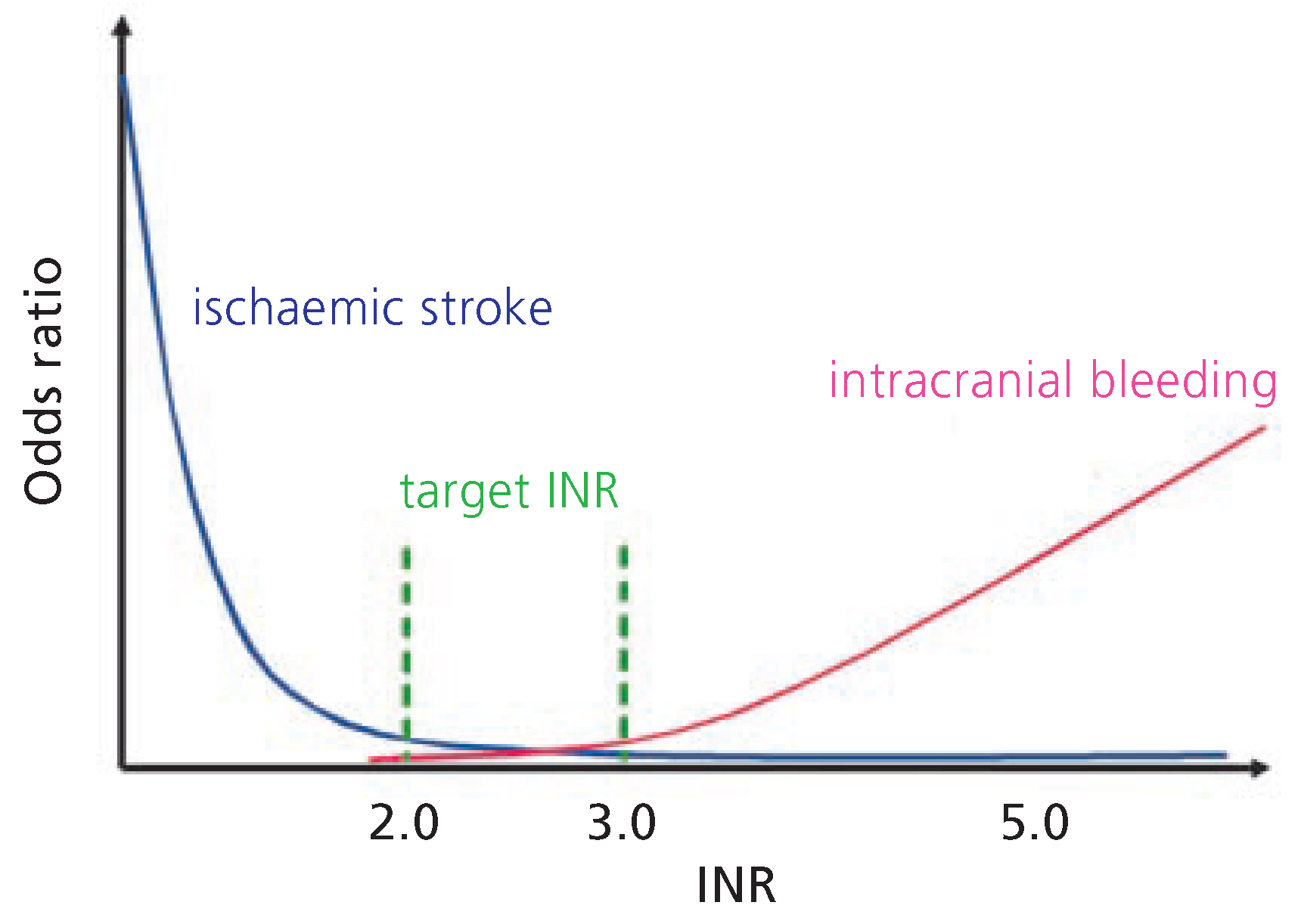

12], the decision of how to anticoagulate these patients should be performed on an individual basis. With respect to the intensity of anticoagulation, an INR >3.0 does not seem to provide a higher grade of protection for the occurrence of an ischaemic stroke; in contrast, an INR <2.0 does not appear to be associated with a lower risk for intracranial haemorrhage as compared to INR ratios between 2.0 and 3.0 [

11,

13]. Hence, a target INR of 2.0–3.0 offers the best compromise between optimal stroke prevention and risk of major bleeding complications (

Figure 1) [

14]; as such, it is recommended for patients with more than 1 moderate risk factor (class I recommendation, level of evidence A;

Table 2B) [

3].

Relative contraindications for OAC include uncontrolled hypertension (RR >180/100 mm Hg), frequent falls or “blackouts”, inability to comply with treatment as well as gastrointestinal or urinary bleeding within the last six months [

15]. Thus, several trials were conducted to evaluate the efficacy of acetylsalicylic acid (dosed daily) for stroke prevention in patients with AF. In a meta-analysis of trials comparing acetylsalicylic acid with OAC, dose-adjusted warfarin is clearly superior as compared to acetylsalicylic acid alone, providing a >30% risk reduction (5.8% as compared to 8.7%) [

10]. However, when compared to placebo, acetylsalicylic acid intake does offer a modest reduction of ischaemic cerebral events, primarily by reducing the risk of stroke in patients with overt cardiovascular disease as well as by decreasing the risk for non-disabling strokes [

10]. Thus, low-dose acetylsalicylic acid therapy remains a treatment alternative for stroke prevention in patients with no (class I recommendation, level of evidence A) or only one (class IIa recommendation, level of evidence A) moderate risk factor as well as in patients with clear contraindications to OAC (class I recommendation, level of evidence A;

Table 2B) [

3]. Combining OAC with acetylsalicylic acid neither seems to offer a benefit in terms of stroke-risk reduction but increases the risk of intracranial bleeding [

16].

Of note, the type of antithrombotic therapy may in general be selected using the same criteria irrespective of the pattern of AF (ie, paroxysmal, persistent, or permanent—class IIa recommendation, level of evidence B) [

3].

Clopidogrel vs vitamin-K antagonists in atrial fibrilation—the “ACTIVE-W” trial and its implications

Given the strong evidence for the benefit of the thrombocyte P

2Y

12 ADP-receptor antagonist clopidogrel in coronary artery disease, especially after stent placement [

17], a recent study investigated whether clopidogrel plus acetylsalicylic acid would be non-inferior to oral anticoagulation in patients with AF plus one or more risk factors for stroke [

18]. The trial had to be stopped early due to a clear evidence of superiority of OAC with the risk of experiencing a primary outcome (first occurrence of stroke, non-CNS systemic embolus, myocardial infarction, or vascular death) being 3.93% per year in the OAC group as compared to 5.60% in the clopidogrel plus acetylsalicylic acid group (relative risk 1.44 [1.18–1.76; p = 0.0003]) [

18].

Most interesting implications of the AC-TIVE-W study, however, can be derived from the subgroups of the trial. Indeed, it could be shown that in patients randomised to receive OAC, no prior use of OAC at study entry was associated with less INR control during the course of the study (compared to prior OAC use) as well as less of a risk reduction in clinical events (compared to clopidogrel plus acetylsalicylic acid). In addition, patients already on OAC had a lower incidence of major bleeding relative to the Clopidogrel / acetylsalicylic acid arm as compared to those that were newly started on OAC. This confirms the observation that the first 3–6 months of treatment with vitamin-K antagonists are the most dangerous ones [

19,

20].

Furthermore, in all patients randomised to receive OAC, the pre-specified target INR values of 2.0–3.0 were achieved in approximately two thirds of patient months. Striking differences were noted, when patients from centres with good INR control (≥65% of INR in target range) were compared to those with poor INR control (≤65% of INR in target range). Indeed, the latter patients experienced less of a risk reduction in clinical events as well as a higher rate of major bleeding events compared with clopidogrel plus acetylsalicylic acid, whereas in patients with good INR control fewer major bleeding events were noted as compared to those receiving clopidogrel and acetylsalicylic acid. As a result, patients with poor INR control had no net benefit from OAC as compared to those in the clopidogrel plus acetylsalicylic acid arm. On the other hand the bleeding events in patients with well controlled INR values do not exceed the ones with combined platelet inhibition but rather tend to be lower.

In summary, the ACTIVE-W trial confirmed existing evidence supporting the use of OAC in AF patients with risk factors. More importantly, however, the study further underlined the importance of an optimal INR control with respect to the efficacy and safety of OAC in those patients; indeed, patients not achieving good INR control may profit little from OAC as compared to clopidogrel plus acetylsalicylic acid. Furthermore, uncertainty persists with respect to the benefit and safety for patients which are newly started on OAC. Whether or not the addition of clopidogrel to acetylsalicylic acid offers an additional benefit over acetylsalicylic acid alone in patients with contraindications to OAC is currently being investigated in the ACTIVE-A arm of the study [

21].

Outlook and conclusions

Despite the proven efficacy of OAC in AF, difficulties in establishing a stable INR as well as potentially severe bleeding complications pinpoint the demand for novel treatment strategies in these patients. The introduction of ximelagatran, a direct thrombin-inhibitor which is administered orally without the need for coagulation monitoring, seemed to mark an important step forward in this direction. Indeed, in patients with atrial fibrillation and one or more stroke risk factors ximelagatran appeared non-inferior as compared to dose-adjusted OAC with respect to the prevention of disabling or fatal stroke and the occurrence of major bleeding; moreover, combined minor and major haemorrhages appeared to possibly be even lower with ximelagatran than with OAC (RR reduction 14%; p = 0.007) [

22]. However, the occurrence of a severe liver injury as well as an apparent increase in myocardial infarctions resulted first in the non-approval of ximelagatran by the FDA in September 2004 and finally in the voluntary withdrawal of the drug and termination of all remaining clinical trials in February of 2006. Despite this major setback, hopes remain high for other agents currently under investigation; potential drugs include other factor II inhibitors (

eg, dabigatran), factor Xa inhibitors (such as idraparinux, currently tested in the phase III AMADEUS study in AF) [

23] as well as factor VII inhibitors. Moreover, direct inhibition of tissue factor, the initiator of the coagulation cascade, may represent an interesting alternative future treatment strategy [

24].

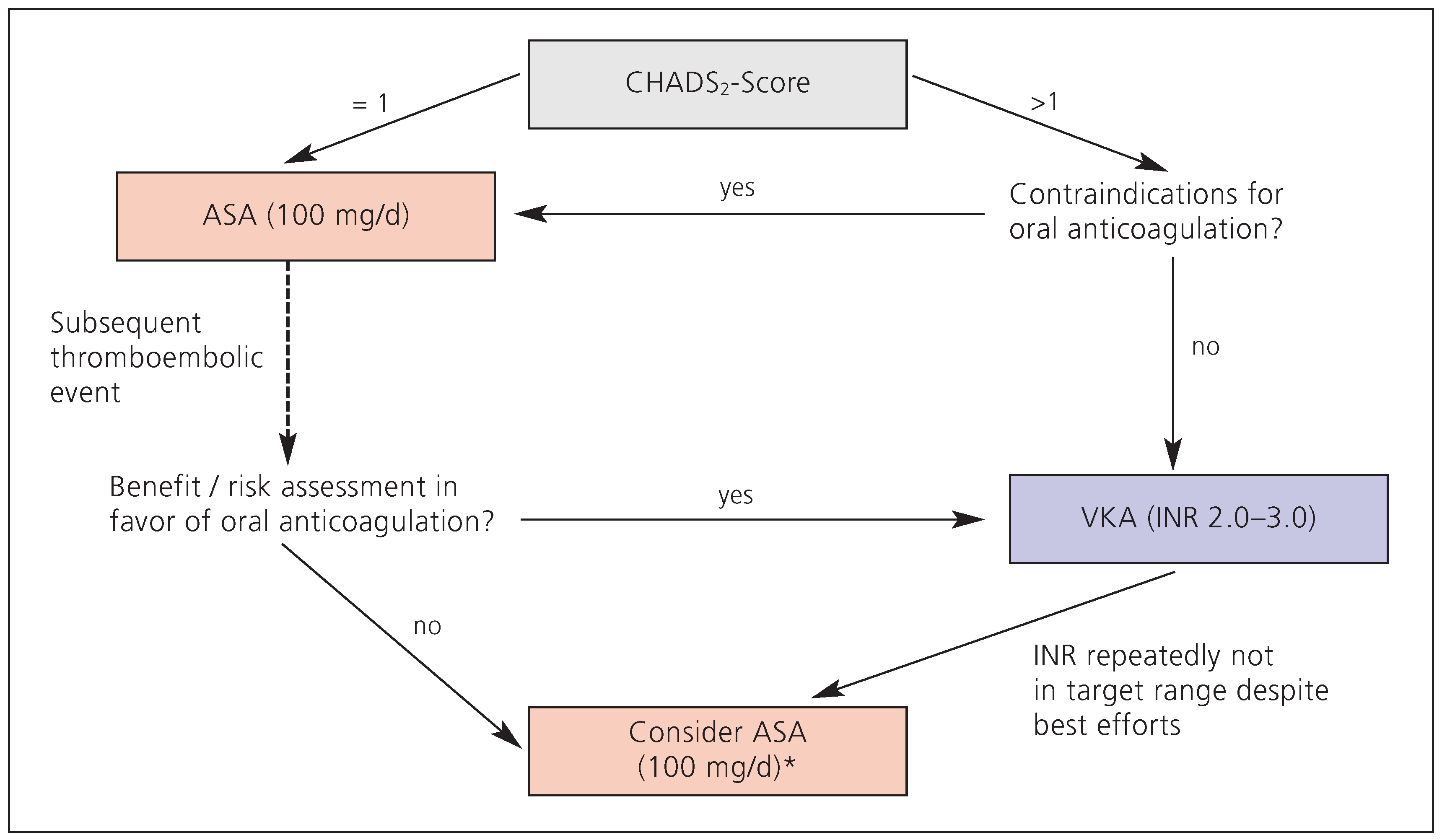

In summary, adequate anticoagulation in patients with AF remains a challenge to both physicians and patients. Depending on the presence or absence of associated cardiovascular risk factors, the adjusted stroke rate of patients with AF ranges from 4–15% per year [

10]. The CHADS

2 score provides an easy-to-use risk-assessment score to classify patients according to the most reliable clinical predictors. In order to provide optimal care for the patient, a risk-benefit assessment with respect to the mode of anticoagulation has to be performed in an individualised manner (class I recommendation, level of evidence A). In general, only low-risk patients or patients with contraindications to OAC are considered to profit from acetylsalicylic acid therapy alone for stroke prevention; in contrast, there is strong evidence that moderate- to high-risk patients should be treated with oral anticoagulation. For these patients, a target INR of 2.0–3.0 offers the best degree of anticoagulation for optimal stroke prevention while keeping the risk of major bleeding complications (in particular intracranial haemorrhage) at a minimum. This appears even more important as retrospective analyses demonstrated that OAC continues to be substantially underprescribed even in patients with AF who are at high risk for stroke [

20,

25]. In selected patients, self-management of anticoagulation may represent a possibility to decrease both thromboembolic events as well as major haemorrhage [

26]. However, if a good INR control cannot be reached despite best efforts from both the patient and physician, OAC may provide little overall benefit as compared to platelet inhibition; as a consequence, switching these patients to acetylsalicylic acid (perhaps in combination with clopidogrel, depending on the outcome of the ACTIVE-A study) may be considered. In general, the expected value has to clearly exceed the severity of known complications (bleeding in particular). The authors’ recommendations are summarised in

Figure 2.