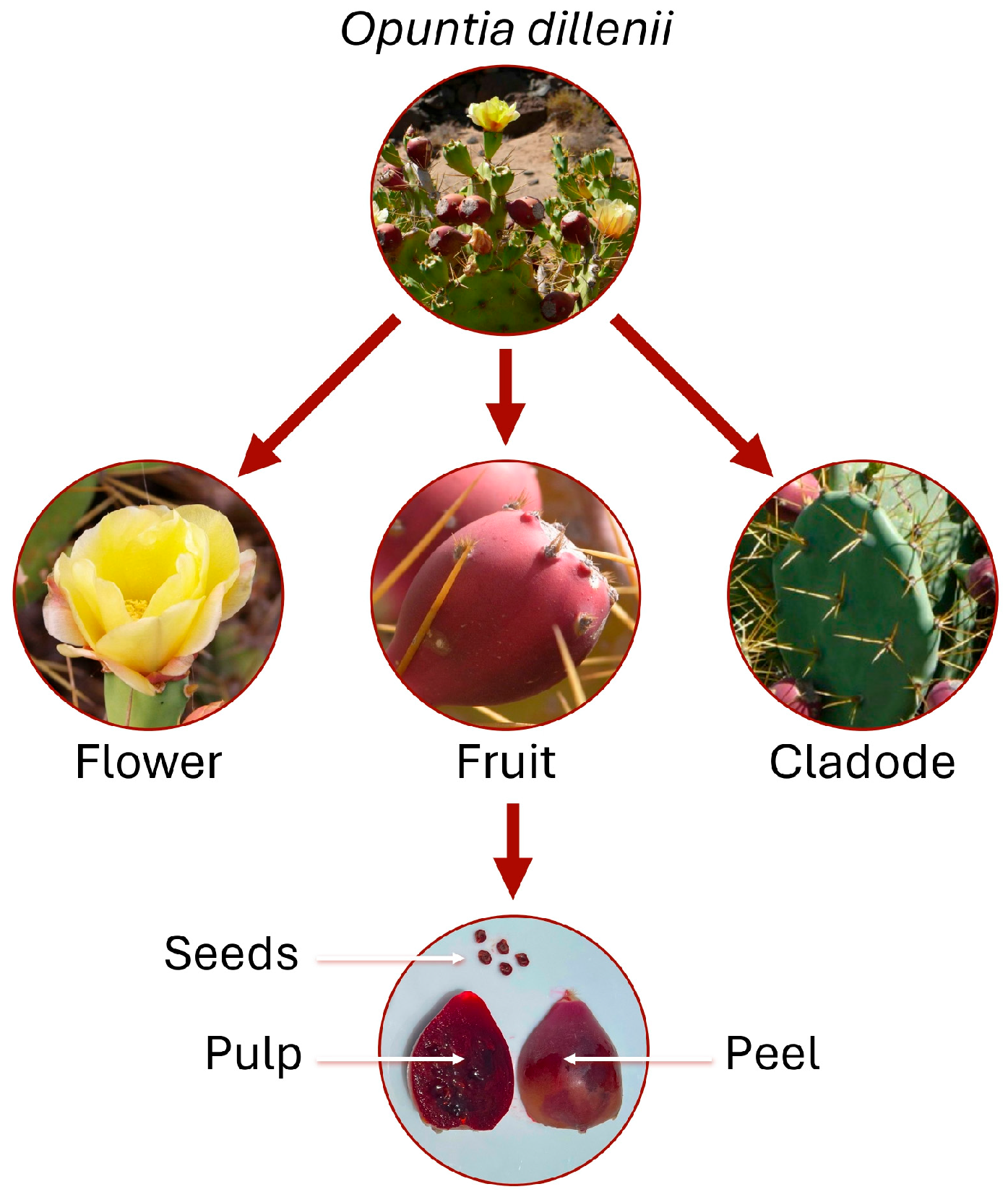

Antioxidant Potential of Opuntia dillenii: A Systematic Review of Influencing Factors and Biological Efficacy

Abstract

1. Introduction

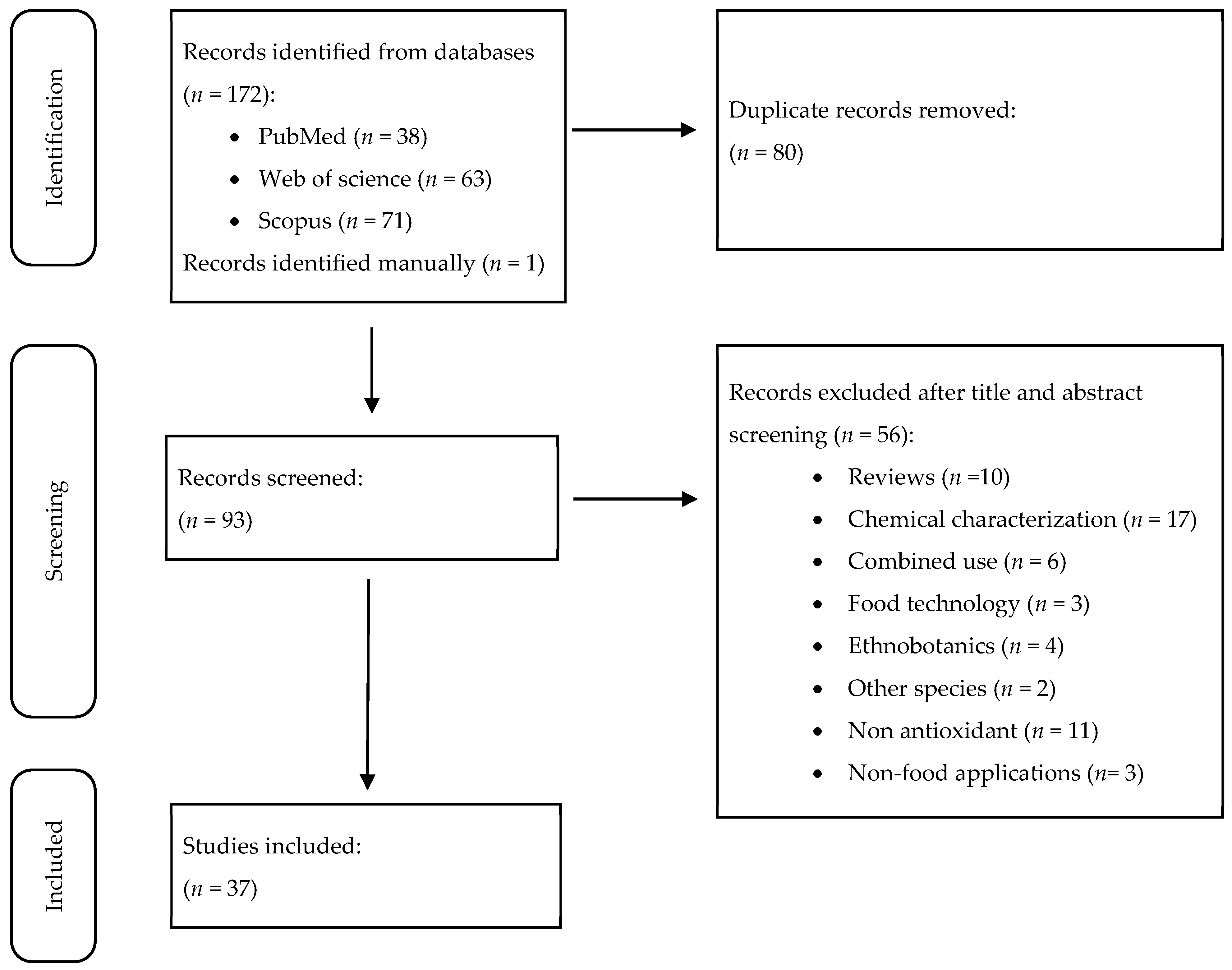

2. Methods

2.1. Data Sources and Search Strategy

2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

2.3. Data Extraction

2.4. Risk of Bias

2.5. Data Synthesis and Qualitative Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Antioxidant Activity Assessed Using in Vitro Chemical-Based Methods

3.1.1. Overview of in Vitro Assays

3.1.2. Antioxidant Potential

3.1.3. Antioxidant Activity According to Plant Part

3.1.4. Extraction Methods and Antioxidant Yield

3.1.5. Identification of Antioxidant Bioactive Compounds

3.1.6. Effect of Maturity Stage on Antioxidant Activity

3.1.7. Geographical Influence on Antioxidant Activity

3.1.8. Impact of Colonic Fermentation on Antioxidant Activity

3.2. Antioxidant Activity in Biological Systems: Cell-Based and Animal Models

3.2.1. Antioxidant Activity in Animal Models

3.2.2. Antioxidant Activity in Cell Culture Studies

3.2.3. Antioxidant Activity in in Silico Study

4. Conclusions and Future Perspectives

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AAE | Ascorbic acid equivalents |

| AAPH | 2,2′-Azodiisobutyramidine dihydrochloride |

| ABTS•+ | 2,2′-Azino-bis (3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonic acid) |

| BHT | Butylated hydroxytoluene |

| BuOH | Butanol |

| CAA | Cellular antioxidant activity |

| CAT | Catalase |

| DEAE | Diethylaminoethyl |

| DCM | Dichloromethane |

| DPPH• | 2,2-Diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl |

| DW | Dry weight |

| EDTA | Ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid |

| EtOAc | Ethyl acetate |

| EtOH | Ethanol |

| FIC | Ferrous ion-chelating |

| FRAP | Ferric reducing antioxidant power |

| GPx | Glutathione peroxidase |

| GSH | Reduced glutathione |

| GSSG | Oxidized glutathione |

| H2O2 | Hydrogen peroxide |

| Hx | Hexane |

| IC50 | Half-maximal inhibitory concentration |

| i.g. | Intragastric administration |

| iNOS | Inducible nitric oxide synthase |

| i.p. | Intraperitoneal administration |

| LPS | Lipopolysaccharide |

| MDA | Malondialdehyde |

| MPO | Myeloperoxidase |

| NADPH | Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate |

| NO• | Nitric oxide |

| NQO1 | NAD(P)H: quinone oxidoreductase 1 |

| O2−• | Superoxide anion |

| •OH | Hydroxyl radical |

| ODP | Opuntia dillenii polysaccharide |

| ORAC | Oxygen radical absorbance capacity |

| p.o. | Per Os (oral administration) |

| ROS | Reactive oxygen species |

| SOD | Superoxide dismutase |

| TAC | Total antioxidant capacity |

| TE | Trolox equivalents |

References

- Sies, H.; Berndt, C.; Jones, D.P. Oxidative Stress. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2017, 86, 715–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharifi-Rad, M.; Anil Kumar, N.V.; Zucca, P.; Varoni, E.M.; Dini, L.; Panzarini, E.; Rajkovic, J.; Fokou, P.V.T.; Azzini, E.; Peluso, I.; et al. Lifestyle, Oxidative Stress, and Antioxidants: Back and Forth in the Pathophysiology of Chronic Diseases. Front. Physiol. 2020, 11, 694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jomova, K.; Raptova, R.; Alomar, S.Y.; Alwasel, S.H.; Nepovimova, E.; Kuca, K.; Valko, M. Reactive oxygen species, toxicity, oxidative stress, and antioxidants: Chronic diseases and aging. Arch. Toxicol. 2023, 97, 2499–2574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muscolo, A.; Mariateresa, O.; Giulio, T.; Mariateresa, R. Oxidative Stress: The Role of Antioxidant Phytochemicals in the Prevention and Treatment of Diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 3264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunyadi, A. The Mechanism(s) of action of antioxidants: From scavenging reactive oxygen/nitrogen species to redox signaling and the generation of bioactive secondary metabolites. Med. Res. Rev. 2019, 39, 2505–2533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, C.; de Paula, C.D.; Lahbouki, S.; Meddich, A.; Outzourhit, A.; Rashad, M.; Pari, L.; Coelhoso, I.; Fernando, A.L.; Souza, V.G.L. Opuntia spp.: An Overview of the Bioactive Profile and Food Applications of This Versatile Crop Adapted to Arid Lands. Foods 2023, 12, 1465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shirazinia, R.; Rahimi, V.B.; Kehkhaie, A.R.; Sahebkar, A.; Rakhshandeh, H.; Askari, V.R. Opuntia dillenii: A forgotten plant with promising pharmacological properties. J. Pharmacopunct. 2019, 22, 16–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Land, E.O.; Casanova, G.G. Opuntia tuna (L.) Mill. In the Canary Islands Biodiversity Database (Banco de Datos de Biodiversidad de Canarias), Government of the Canary Islands. Available online: https://www.biodiversidadcanarias.es/biota/especie/F00241 (accessed on 7 July 2025).

- Loukili, E.H.; Merzouki, M.; Taibi, M.; Elbouzidi, A.; Hammouti, B.; Yadav, K.K.; Khalid, M.; Addi, M.; Ramdani, M.; Kumar, P.; et al. Phytochemical, Biological, and Nutritional Properties of the Prickly Pear, Opuntia dillenii: A Review. Saudi Pharm. J. 2024, 32, 102167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ardisana, E.F.H. The Future of Opuntia spp.: Sustainability and Global Impact. In Opuntia spp.: Superfood of the Future and its Biotechnological Potential, 1st ed.; Pérez-Álvarez, S., Ardisana, E.F.H., Eds.; Deep Science Publishing: London, UK, 2025; pp. 60–75. [Google Scholar]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 Statement: An Updated Guideline for Reporting Systematic Reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; Moher, D.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. PRISMA 2020 Explanation and Elaboration: Updated Guidance and Exemplars for Reporting Systematic Reviews. BMJ 2021, 371, n160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hooijmans, C.R.; Rovers, M.M.; de Vries, R.B.M.; Leenaars, M.; Ritskes-Hoitinga, M.; Langendam, M.W. SYRCLE’s risk of bias tool for animal studies. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2014, 14, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez-Moreno, C. Review: Methods Used to Evaluate the Free Radical Scavenging Activity in Foods and Biological Systems. Food Sci. Technol. Int. 2002, 8, 121–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gulcin, İ.; Alwasel, S.H. Fe3+ Reducing Power as the Most Common Assay for Understanding the Biological Functions of Antioxidants. Processes 2025, 13, 1296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gulcin, İ.; Alwasel, S.H. Metal Ions, Metal Chelators and Metal Chelating Assay as Antioxidant Method. Processes 2022, 10, 132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laguerre, M.; Lecomte, J.; Villeneuve, P. Evaluation of the Ability of Antioxidants to Counteract Lipid Oxidation: Existing Methods, New Trends and Challenges. Prog. Lipid Res. 2007, 46, 244–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badami, S.; Channabasavaraj, K.P. In Vitro Antioxidant Activity of Thirteen Medicinal Plants of India’s Western Ghats. Pharm. Biol. 2007, 45, 392–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, S.-F.; Hsieh, C.-L.; Yen, G.-C. The protective effect of Opuntia dillenii Haw fruit against low-density lipoprotein peroxidation and its active compounds. Food Chem. 2008, 106, 569–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Fu, Y.-J.; Zu, Y.-G.; Tong, M.-H.; Wu, N.; Liu, X.-L.; Zhang, S. Supercritical carbon dioxide extraction of seed oil from Opuntia dillenii Haw. and its antioxidant activity. Food Chem. 2009, 114, 334–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loganayaki, N.; Manian, S. In Vitro antioxidant properties of indigenous underutilized fruits. Food Sci. Biotechnol. 2010, 19, 725–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Q.; Chen, H.; Zhou, X.; Zhang, J. Optimum extraction of polysaccharides from Opuntia dillenii and evaluation of its antioxidant activities. Carbohydr. Polym. 2013, 97, 736–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.S.; Ganesh, M.; Peng, M.M.; Jang, H.T. Phytochemical, antioxidant, antiviral and cytotoxic evaluation of Opuntia dillenii flowers. Bangladesh J. Pharmacol. 2014, 9, 351–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghazi, Z.; Ramdani, M.; Tahri, M.; Rmili, R.; Elmsellem, H.; El Mahi, B.; Fauconnier, M.-L. Chemical Composition and Antioxidant Activity of seeds oils and fruit juice of Opuntia ficus indica and Opuntia dillenii from Morocco. J. Mater. Environ. Sci. 2015, 6, 2338–2345. [Google Scholar]

- Li, H.; Yuan, Q.; Zhou, X.; Zeng, F.; Lu, X. Extraction of Opuntia dillenii Haw. Polysaccharides and Their Antioxidant Activities. Molecules 2016, 21, 1612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Betancourt, C.; Cejudo-Bastante, M.J.; Heredia, F.J.; Hurtado, N. Pigment composition and antioxidant capacity of betacyanins and betaxanthins fractions of Opuntia dillenii (Ker Gawl) haw cactus fruit. Food Res. Int. 2017, 101, 173–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alsaad, A.J.A.; Altemimi, A.B.; Aziz, S.N.; Lakhssassi, N. Extraction and identification of cactus Opuntia dillenii seed oil and its added value for human health benefits. Pharmacogn. J. 2019, 11, 579–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katanić, J.; Yousfi, F.; Caruso, M.C.; Matić, S.; Monti, D.M.; Loukili, E.H.; Boroja, T.; Mihailović, V.; Galgano, F.; Imbimbo, P.; et al. Characterization of bioactivity and phytochemical composition with toxicity studies of different Opuntia dillenii extracts from Morocco. Food Biosci. 2019, 30, 100410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouhrim, M.; Daoudi, N.E.; Ouassou, H.; Benoutman, A.; Loukili, E.H.; Ziyyat, A.; Mekhfi, H.; Legssyer, A.; Aziz, M.; Bnouham, M. Phenolic Content and Antioxidant, Antihyperlipidemic, and Antidiabetogenic Effects of Opuntia dillenii Seed Oil. Sci. World J. 2020, 2020, 5717052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsaad, A.J.A.; Mohammed, L.S. Study of the Antioxidant Activity of Cactus (Opuntia dellienii) Fruits (Pulp and Peels) and Characterisation of Their Bioactive Compounds by GC-MS. Basrah J. Agric. Sci. 2021, 34, 204–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben Lataief, S.; Zourgui, M.-N.; Rahmani, R.; Najjaa, H.; Gharsallah, N.; Zourgui, L. Chemical composition, antioxidant, antimicrobial and cytotoxic activities of bioactive compounds extracted from Opuntia dillenii cladodes. J. Food Meas. Charact. 2021, 15, 782–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-López, I.; Lobo-Rodrigo, G.; Portillo, M.P.; Cano, M.P. Ultrasound-Assisted “Green” Extraction (UAE) of Antioxidant Compounds (Betalains and Phenolics) from Opuntia stricta Var. dilenii’s Fruits: Optimization and Biological Activities. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 1786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gomez-Maqueo, A.; Soccio, M.; Cano, M.P. In Vitro Antioxidant Capacity of Opuntia Spp. Fruits Measured by the LOX-FL Method and Its High Sensitivity Towards Betalains. Plant Foods Hum. Nutr. 2021, 76, 354–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vieira, E.A.; Coêlho, J.G.S.; Grisi, C.V.B.; Santos, B.S.; Silva Junior, J.C.; Alcântara, M.A.; Meireles, B.R.L.A.; Santos, N.A.; Cordeiro, A.M.R.T.M. Correlation and influence of antioxidant compounds of peels and pulps of different species of cacti from Brazilian caatinga biome using principal component analysis. S. Afr. J. Bot. 2022, 147, 434–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-López, I.; Mendiola, J.A.; Portillo, M.P.; Cano, M.P. Pressurized green liquid extraction of betalains and phenolic compounds from Opuntia stricta Var. dillenii whole fruit: Process optimization and biological activities of green extracts. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 2022, 80, 103066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Sousa Rocha, S.; da Silva, S.R.F.; da Silva, J.Y.P.; de Medeiros, V.P.B.; Aburjaile, F.F.; de Oliveira Carvalho, R.D.; da Silva, M.S.; Tavares, J.F.; do Nascimento, Y.M.; dos Santos Lima, M.; et al. Exploring the potential prebiotic effects of Opuntia dillenii (Ker Gawl). Haw (Cactaceae) cladodes on human intestinal microbiota. J. Funct. Foods 2024, 118, 106259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Hassania, L.; Mounime, K.; Elbouzidi, A.; Taibi, M.; Mohamed, C.; Abdelkhaleq, L.; Mohammed, R.; Naceiri Mrabti, H.; Zengin, G.; Addi, M.; et al. Analyzing the Bioactive Properties and Volatile Profiles Characteristics of Opuntia dillenii (Ker Gawl.) Haw: Exploring Its Potential for Pharmacological Applications. Chem. Biodivers. 2024, 21, e202301890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elouazkiti, M.; Zefzoufi, M.; Elyacoubi, H.; Gadhi, C.; Bouamama, H.; Rochdi, A. Phytochemical Analysis and Bioactive Properties of Opuntia dillenii Flower Extracts, Compound, and Essential Oil. Int. J. Food Sci. 2024, 2024, 6131664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marhri, A.; Rbah, Y.; Allay, A.; Boumediene, M.; Tikent, A.; Benmoumen, A.; Melhaoui, R.; Elamrani, A.; Abid, M.; Addi, M. Comparative Analysis of Antioxidant Potency and Phenolic Compounds in Fruit Peel of Opuntia robusta, Opuntia dillenii, and Opuntia ficus-indica Using HPLC-DAD Profiling. J. Food Qual. 2024, 2024, 2742606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marhri, A.; Rbah, Y.; Allay, A.; Boumediene, M.; Tikent, A.; Benmoumen, A.; Melhaoui, R.; Elamrani, A.; Abid, M.; Addi, M. HPLC-DAD Profiling of Phenolic Components and Comparative Assessment of Antioxidant Potency in Opuntia robusta, Opuntia dillenii, and Opuntia ficus-indica Cladodes at Diverse Stages of Ripening. Oleo Sci. 2024, 73, 1529–1540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rehioui, M.; Benzidia, B.; Abbout, S.; Barbouchi, M.; Erramli, H.; Hajjaji, N. Physicochemical properties of Moroccan Opuntia dillenii fruit, extraction of betacyanins and study of its stability and antioxidant activity. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. Food Sci. 2024, 14, e9098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anavi, S.; Tirosh, O. iNOS as a metabolic enzyme under stress conditions. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2020, 146, 16–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolfe, K.L.; Liu, R.H. Cellular antioxidant activity (CAA) assay for assessing antioxidants, foods, and dietary supplements. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2007, 55, 8896–8907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cipak Gasparovic, A.; Zarkovic, N.; Zarkovic, K.; Semen, K.; Kaminskyy, D.; Yelisyeyeva, O.; Bottari, S.P. Biomarkers of oxidative and nitro-oxidative stress: Conventional and novel approaches. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2017, 174, 1771–1783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mhya, D.H.; Jakwa, A.G.; Agbo, J. In Silico Analysis of Antioxidant Phytochemicals with Potential NADPH Oxidase Inhibitory Effect. J. Health Sci. Med. Res. 2023, 41, e2022912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Li, Q.; Li, H.; Guo, L. Neuroprotective and antioxidative effect of cactus polysaccharides In Vivo and In Vitro. Cell Mol. Neurobiol. 2009, 29, 1211–1221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.Y.; Lan, Q.J.; Huang, Z.C.; Ouyang, L.J.; Zeng, F.H. antidiabetic effect of a newly identified component of Opuntia dillenii polysaccharides. Phytomedicine 2011, 18, 661–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.; Han, Y.-L.; Jin, Z.-Y.; Xu, X.-M.; Zha, X.-Q.; Chen, H.-Q.; Yin, Y.-Y. Protective effect of polysaccharides from Opuntia dillenii Haw. fruits on streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats. Carbohydr. Polym. 2015, 124, 25–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouhrim, M.; Ouassou, H.; Choukri, M.; Mekhfi, H.; Ziyyat, A.; Legssyer, A.; Aziz, M.; Bnouham, M. Hepatoprotective effect of Opuntia dillenii seed oil on CCl4 induced acute liver damage in rat. Asian Pac. J. Trop. Biomed. 2018, 8, 254–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babitha, S.; Bindu, K.; Nageena, T.; Veerapur, V.P. Fresh Fruit Juice of Opuntia dillenii Haw. Attenuates Acetic Acid–Induced Ulcerative Colitis in Rats. J. Diet. Suppl. 2019, 16, 431–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahmad, M.A.; Babitha, S.; Tejaskumar, H.; Pooja, T.; Veerapur, V.P. Fresh fruit juice of Opuntia dillenii Haw attenuates paracetamol induced hepatotoxicity in rats. Res. J. Pharm. Technol. 2020, 13, 3317–3322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shirazinia, R.; Golabchifar, A.A.; Rahimi, V.B.; Jamshidian, A.; Samzadeh-Kermani, A.; Hasanein, P.; Hajinezhad, M.; Askari, V.R. Protective Effect of Opuntia dillenii Haw Fruit against Lead Acetate-Induced Hepatotoxicity: In Vitro and In Vivo Studies. Evid. Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2021, 2021, 6698345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelkader Saidi, S.; Al-Shaikh, T.M.; Hamden, K. Evaluation of Gastroprotective Effect of Betalain-Rich Ethanol Extract from Opuntia stricta Var. dillenii Employing an In Vivo Rat Model. J. Food Qual. 2023, 2023, 2215454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Besné-Eseverri, I.; Martín, M.Á.; Lobo, G.; Cano, M.P.; Portillo, M.P.; Trepiana, J. Antioxidant and Anti-Inflammatory Effects of Opuntia Extracts on a Model of Diet-Induced Steatosis. Antioxidants 2024, 13, 1416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haq, I.U.; Mirza, B.; Kondratyuk, T.P.; Park, E.-J.; Burns, B.E.; Marler, L.E.; Pezzuto, J.M. Preliminary evaluation for cancer chemopreventive and cytotoxic potential of naturally growing ethnobotanically selected plants of Pakistan. Pharm. Biol. 2013, 51, 316–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, R.; Chu, F.; Yan, Z.; Chen, H. Structural characterization of three acidic polysaccharides from Opuntia dillenii Haw. fruits and their protective effect against hydrogen peroxide-induced oxidative stress in Huh-7 cells. Food Sci. Hum. Wellness 2024, 13, 1929–1942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parralejo-Sanz, S.; Antunes-Ricardo, M.; Lobo, M.G.; Requena, T.; Cano, M.P. Assessment of the Immunomodulatory Potential of Betalain- and Phenolic-Rich Extracts from Opuntia Cactus Fruits. Food Biosci. 2025, 65, 106093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serrano-Sandoval, S.N.; Parralejo-Sanz, S.; Lobo, M.G.; Cano, M.P.; Antunes-Ricardo, M. A bio-Guided search of anti-steatotic compounds in Opuntia stricta var. dillenii by fast centrifugal partition chromatography. Food Chem. 2025, 464, 141682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Assay | Mechanism of Action | Targeted Reactive Species | Applicability |

|---|---|---|---|

| DPPH• and ABTS•+ | Radical scavenging (electron/hydrogen donation) | DPPH• and ABTS•+ radicals | Measures the ability to neutralize free radicals |

| FRAP | Reduction of Fe3+ (single electron transfer) | N/A (measure of reducing power) | Measures the ability to donate electrons |

| TAC | Reduction of molybdate (single electron transfer) | ||

| ORAC | Radical scavenging (hydrogen atom transfer) | ROO• radical | Measures the capacity to neutralize ROO• radicals and inhibit lipid oxidation |

| β-Carotene bleaching | Radical scavenging (single electron transfer) | ||

| Lipid peroxidation | Radical scavenging (hydrogen atom transfer) | ||

| ROS scavenging assays | Radical scavenging (hydrogen atom transfer) | •OH, H2O2, O2•−, and NO• | Evaluates antioxidant activity against biologically relevant ROS |

| FIC | Metal ion chelation | Fe2+ | Assesses the ability to chelate iron ions, preventing radical formation |

| Plant Part | Extraction Method | Assay | Results | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fruit or cladodes | Methanolic extraction (1:5, w/v) for 7 days | Lipid peroxidation DPPH• ABTS•+•OH H2O2 NO• TAC [µg/mL]: 0.45–1000 | IC50 (µg/mL): fruit vs. cladodes Lipid peroxidation: 353 vs. 87 DPPH•: 317 vs. >1000 ABTS•+: 46 vs. 27 •OH: >1000 in both H2O2: >1000 in both NO•: >700 in both TAC (µM AAE/g): fruit vs. cladodes 1.4 vs. 0.4 | [18] |

| Peel, pulp, and seeds from fruit | Two successive methanolic extractions (1:1, w/v) for 1 h at 4 °C, followed by centrifugation (14,000× g, 10 min) | ABTS•+ and ORAC (1 mg/mL) Lipid peroxidation (10 µg/mL) | Peel vs. pulp vs. seeds ABTS•+ (μM TE) 1.24 vs. 1.01 vs. 2.15 ORAC (μM TE) 0.14 vs. 0.10 vs. 0.18 Lipid peroxidation (% inhibition) 76.4 vs. 73.2 vs. 92.3 | [19] |

| Seeds | Supercritical CO2 fluid extraction of seed oil (46.96 MPa, 46.51 °C, 2.79 h, and CO2 flow rate of 10 kg/h) | DPPH• β-carotene bleaching [%, v/v]: 10–100 | IC50 (%, v/v) DPPH•: 11.4 β-Carotene bleaching: 20.7 | [20] |

| Whole fruit | Two successive methanolic extractions (1:5, w/v) using mechanical shaker for 24 h at 25 °C, followed by centrifugation (6000× g, 10 min) | DPPH• ABTS•+ FIC FRAP β-carotene bleaching | DPPH• (IC50, µg/mL): 43.0 ABTS•+ (μmol TE/g): 7290.0 FIC (mg EDTA/g): 10.8 FRAP (mmol Fe2+/g): 998.9 β-Carotene bleaching (% inhibition): 19.6 | [21] |

| Not specified | Two successive aqueous extractions (1:8–1:12, w/v) in a shaking water bath (100 rpm, 80–90 °C, 50–70 min), followed by centrifugation (6000 rpm, 15 min) and isolation of polysaccharides via 80% ethanol precipitation (24 h) and washing with ethanol and acetone | DPPH• | Higher polysaccharide purity (27.4–90.1%) was associated with stronger antioxidant activity (IC50, 3105–408 µg/mL) | [22] |

| Flowers | Bolling methanolic extraction (1:10, w/v), followed by centrifugation (150× g, 15 min) | DPPH• •OH H2O2 [µg/mL]: 10–500 | IC50 (µg/mL) DPPH•: 58.7 •OH: 159.7 H2O2: 131.1 | [23] |

| Seeds and fruit pulp | Seed: organic solvent extraction of oil (1:2.5, w/v) for 2 h Pulp juice: mixing of seedless pulp for 5 min | DPPH• [µg/mL]: 5–20 | IC50 (µg/mL) Oil: 27.2 Pulp juice 8.2 | [24] |

| Cladodes from tender (2–4-month-old) and old (5–10-month-old) plants | Polysaccharide extract: aqueous extraction (1:60, w/v), for 3 h at 95 °C, followed by centrifugation (1810× g, 15 min) and protein removal Polysaccharide fractions from tender plant (I, Ia, Ib, II, IIa, and IIb): DEAE-cellulose anion exchange chromatography and Sephacryl S-400 gel filtration | DPPH• •OH O2−• [mg/mL]: 6.4 | Radical-scavenging activity (%) DPPH•: tender (60.5), old (58.1), I (46.2), Ia (58.4), Ib (15.3), II (33.9), IIa (45.6), and IIb (8.8) •OH: tender (39.6), old (46.2), I (39.8), Ia (45.7), Ib (12.5), II (39.1), IIa (41.4), and IIb (0.8) O2−•: tender (37.4), old (29.1), I (36.5), Ia (43.7), Ib (13.4), II (30.0), IIa (37.2), and IIb (5.2) | [25] |

| Fruit | Crude extract: 60% methanol extraction at 10 °C, until discoloration Purified extract: removal of hydrocolloids and proteins from the crude extract Yellow/red fraction: chromatographic separation (column C18) of the purified extract | ABTS•+ | Radical-scavenging activity (μmol TE/g fresh fruit) Crude extract: 35.2 Purified extract: 15.7 Yellow fraction: 1.7 Red fraction: 5.4 | [26] |

| Seeds | Hydro distillation extraction of essential oil (1:20, w/v), for 4.5 h, followed by centrifugation (5000 rpm, 2 min) | DPPH• [µg/mL]: 10–1000 | Radical-scavenging activity 36.5–78.1% | [27] |

| Seeds, fruit peel, and fruit pulp juice from two Moroccan regions (Nador and Essaouira) | Organic solvent extraction: diethyl ether maceration (1:2.2, w/v) for 24 h, followed by extraction with diethyl ether (Et2O), ethyl acetate (EtOAc), or ethanol (EtOH) Water extraction of the powder recovered after organic extraction | DPPH• ABTS•+ TAC | Nador vs. Essaouira DPPH• (IC50, µg/mL) Peel: Et2O: 190 vs. >2000; EtOAc: 720 vs. 340; EtOH: 530 vs. 500; water: >2000 vs. 880 Seed: Et2O: 119 vs. >2000; EtOAc: 220 vs. 380; EtOH: 63 vs. 45; water: >2000 in both Juice: Et2O: 1340 vs. 370; EtOAc: >2000 vs. 850; EtOH: 1450 vs. 280; water: 690 vs. 370 ABTS•+ (IC50, µg/mL) Peel: Et2O: 550 vs. 570; EtOAc: 536 vs. 307; EtOH: 736 vs. 460; Water: 970 vs. 820 Seed: Et2O: >2000 in both; EtOAc: 920 vs. 857; EtOH: 130 vs. 88; water: 700 vs. 380 Juice: Et2O: >2000 vs. 190; EtOAc: >2000 vs. 95; EtOH: 1660 vs. 100; water: 750 vs. 213 TAC (mg AAE/g DW) Peel: Et2O: 190 vs. 140; EtOAc: 130 vs. 190; EtOH: 150 vs. 240; water: 82 vs. 77 Seed: Et2O: 95 vs. 92; EtOAc: 130 vs. 129; EtOH: 281 vs. 410; water: 71 vs. 110 Juice: Et2O: 73 vs. 230; EtOAc: 53 vs. 220; EtOH: 64 vs. 420; water: 84 vs. 830 | [28] |

| Seeds | Extraction of essential oil with petroleum ether (1:5, w/v) for 24 h | DPPH• [mg/mL]: 0.1–6 | IC50 0.38 mg/mL | [29] |

| Fruit peel and pulp | Polar (ethanol) and non-polar (hexane) solvent extractions (1:30, w/v) for 48 h | DPPH• [µg/mL]: 20–80 | Radical-scavenging activity (%) Ethanol + peel: 34.8–75.0 Ethanol + pulp: 32.9–71.8 Hexane + peel: 24.9–62.7 Hexane + pulp: 20.7–56.0 | [30] |

| Cladodes | Aqueous or ethanolic extraction (1:4, w/v) for 24 h | DPPH• ABTS•+ TAC FRAP NO• | Water vs. ethanol DPPH• (IC50, mg/mL): 0.54 vs. 0.60 ABTS•+ (mM TE/g): 0.46 vs. 0.59 TAC (mg AAE/g): 60.44 vs. 62.99 FRAP (Abs 700 nm): 1.39 vs. 1.97 NO• (IC50, mg/mL): 0.15 vs. 0.06 | [31] |

| Whole seedless fruit | Ultrasound-assisted extraction with ethanol (1:50, w/v) for 5 min, at different temperatures (20–50 °C), amplitudes (20–50%), and ethanol concentration (15–80%), followed by centrifugation (10,000× g) Standard extraction: 50% methanolic extraction (1:30, w/v) with Ultraturax (25,000 rpm, 2 min), followed by centrifugation (10,000 rpm, 10 min) and two successive re-extractions with 50% and 100% methanol | ORAC | Radical-scavenging activity (µmol TE/g DW) Ultrasound-assisted extraction: 330.7–618.9 Standard extraction: 151.8 | [32] |

| Peels and pulp from fruit | Three successive 50% methanol extractions, followed by pure methanol extraction | ABTS•+ ORAC | Peel vs. pulps (µmol TE/g DW) ABTS•+: 102.6 vs. 99.5 ORAC: 115.4 vs. 160.0 | [33] |

| Peels and pulp from fruit | Ethanolic extraction (1:10, w/v) at 30 °C, for 4 h with stirring (200 rpm), followed by centrifugation (2800× g, 15 min) | DPPH• FRAP β-carotene bleaching | Peel vs. pulps DPPH• (µmol TE/g DW): 53.1 vs. 26.7 FRAP (µmol TE/g DW): 17.4 vs. 2.3 β-Carotene (% inhibition): 53.8 vs. 51.9 | [34] |

| Whole seedless fruit | Pressurized liquid extraction with ethanol for 10 min with constant pressure (10.34 MPa), at different temperatures (25–65 °C) and ethanol concentration in water (0–100%, v/v) Standard extraction: 50% methanolic extraction (1:30, w/v) with Ultraturax (25,000 rpm, 2 min), followed by centrifugation (10,000 rpm, 10 min) and two successive re-extractions with 50% methanol and 100% methanol | ORAC | Radical-scavenging activity (µmol TE/g DW) Pressurized liquid extraction: 321.4–470.7 Standard extraction: 151.8 | [35] |

| Cladodes pulp | 48 h anaerobic in vitro colonic fermentation (40:40:20 v/v/w medium/inoculum/cladodes) | DPPH• ABTS•+ FRAP | 0 vs. 24 vs. 48 h of colonic fermentation DPPH• (µmol TE/g): 0.30 vs. 0.26 vs. 0.20 ABTS•+ (µmol TE/g): 0.22 vs. 0.27 vs. 0.28 FRAP (µmol FeSO4/g): 2.84 vs. 3.49 vs. 4.13 | [36] |

| Seeds of three variants: Aknari (AK), Harmoucha (HA), and Imtchan (IM) | Cold pressing extraction of essential oil for 45 min | DPPH• FRAP FIC | IC50 (µg/mL): AK vs. HA vs. IM DPPH•: 38.4 vs. 42.2 vs. 15.2 FRAP: 30.2 vs. 55.9 vs. 23.4 FIC: 42.8 vs. 39.5 vs. 35.3 | [37] |

| Flowers and seeds | Flowers: 70% ethanolic (EtOH) extraction (4 days), followed or not by liquid–liquid extraction with hexane (Hx), dichloromethane (DCM), ethyl acetate (EtOAc), or butanol (BuOH) Seeds: steam-distillation followed purification of essential oil with Hx | DPPH• FRAP | DPPH• (IC50) Hx < DCM < oils < BuOH = EtOAc < EtOH FRAP (IC50) Hx < oils < DCM < BuOH = EtOAc < EtOH | [38] |

| Fruit peel | 50% acetone extraction (1:50, w/v) with vortexing for 10 min, followed by centrifugation (5000 rpm, 15 min) | DPPH• ABTS•+ FRAP TAC | mg TE/g DW DPPH•: 1.2 ABTS•+: 0.4 FRAP: 0.8 TAC: 19.2 | [39] |

| Tender (<1 year) and old (>2 years) cladodes | 50% acetone extraction (1:50, w/v) with vortexing for 10 min, followed by centrifugation (5000 rpm, 15 min) | DPPH• ABTS•+ FRAP TAC | mg TE/g DW: tender vs. old DPPH•: 0.82 vs. 0.58 ABTS•+: 0.30 vs. 0.43 FRAP: 0.42 vs. 0.92 TAC: 15.56 vs. 15.12 | [40] |

| Fruit pulp | Betacyanin extraction with 50% ethanol (1:2, w/v) for 24 h, followed centrifugation (5000 rpm, 10 min) | DPPH• TAC | DPPH• (IC50, mg/mL): 2.4 TAC (mg AA/g): 273.3 | [41] |

| Biological Model | Treatment | Assay | Results | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Animal model studies | ||||

| MCAO-induced cerebral ischemia in male Sprague–Dawley rats | Single dose (200 mg/kg) of polysaccharide extract (i.p.) | iNOS protein expression in cortex | ↓ iNOS | [46] |

| Streptozotocin-induced diabetes in male Chinese Kunming mice | 50, 100, or 200 mg/kg/day of polysaccharide extracted from cladodes for 21 days (i.g.) | Liver levels of MDA and antioxidant enzyme activity (SOD and GPx) | ↓ MDA (27, 39, and 40%) at all doses ↑ SOD (18 and 22%) at 100 and 200 mg/kg ↑ GPx (54, 58, and 82%) at all doses | [47] |

| Streptozotocin-induced diabetes in male Sprague–Dawley rats | 50, 100, or 200 mg/kg/day of polysaccharide extracted from pulp fruit for 28 days (p.o.) | Serum, liver, kidney, and pancreatic levels of MDA and antioxidant enzyme activity (SOD, CAT, and GPx) | Effect with 200 mg/kg ↓ MDA (44, 25, 31, and 26%) ↑ SOD (30, 17, 17, and 99%) ↑ CAT (283, 108, 66, and 62%) ↑ GPx (58, 20, 55, and 64%) | [48] |

| CCl4-induced liver injury in Wistar rats | 2 mL/kg/day of seed essential oil for 7 days (p.o.) | MDA level in liver | ↓ MDA | [49] |

| Acetic-acid-induced colitis in male albino Wistar rats | 2.5 or 5 mL/kg/day of juice for 7 days (p.o.) | MPO activity, levels of MDA, and GSH content in colon | Effect with both doses ↓ MPO and MDA ↑ GSH | [50] |

| Paracetamol-induced liver injury in albino Wistar rats | 2.5 or 5 mL/kg/day of juice for 7 days (p.o.) | Levels of MDA and GSH, and CAT activity in liver | ↓ MDA (both doses) ↑ GSH (5 mL/kg) ↑ CAT (both doses) | [51] |

| Lead-acetate-induced liver injury in male Wistar rats | 100 or 200 mg/kg/day of pulp fruit extract for 10 days (p.o.) | Levels of MDA and CAT activity in liver | Effect with both doses ↓ MDA ↑ CAT | [52] |

| Ethanol-induced gastric ulcer in male Wistar rats | Single dose (200, 400, or 800 mg/kg) of pulp or peel fruit extract (p.o.) | MDA levels and antioxidant enzyme activity (SOD, CAT, and GPx) in gastric tissue | Effect with 800 mg/kg of pulp vs. peel ↓ MDA (17 vs. 23%) ↑ SOD (55 vs. 102%) ↑ CAT (75 vs. 100%) ↑ GPx (58 vs. 104%) | [53] |

| High-fat/high-fructose diet-induced liver steatosis in male Wistar rats | 25 or 100 mg/kg/day of peel fruit extract for 8 weeks (p.o.) | Levels of MDA and protein carbonyl, antioxidant capacity (ORAC), GSSG/GSH ratio, and antioxidant enzyme activity (SOD, CAT, and GPx) in liver | ↔ CAT, ORAC, and carbonyl protein ↑ GPx at 25 and 100 mg/kg ↑ SOD (87%) at 100 mg/kg ↓ MDA (29%) at 100 mg/kg ↓ GSSG/GSH at 100 mg/kg | [54] |

| Cell culture studies | ||||

| H2O2-induced oxidative stress in rat pheochromocytoma cells (PC12) | 0.1, 0.25, or 0.5 mg/mL of polysaccharide extract for 30 min | Intracellular levels of ROS | ↓ ROS at 0.5 mg/mL | [46] |

| LPS-stimulated murine macrophage (RAW 264.7) Murine liver cells (Hepa 1c1c7) | RAW 264.7: fruit extract for 15 min (concentrations not indicated) Hepa 1c1c7: 20 μg/mL of fruit extract for 48 h | iNOS protein expression (RAW 264.7) NQO1 enzyme activity (Hepa 1c1c7) | ↔ iNOS and NQO1 | [55] |

| Lead-acetate-induced oxidative stress in human liver cells (HepG2) | 20, 40, or 80 μg/mL of pulp fruit extract for 24 h | Intracellular levels of GSH and MDA | ↑ GSH (40 and 80 μg/mL) ↓ MDA (all concentrations) | [52] |

| H2O2-induced oxidative stress in human liver cells (Huh-7) | 50, 100, or 200 μM of polysaccharide fraction with different molecular weights (F1, 804; F2, 555; F3, 415 kDa) from pulp fruit, for 1 h | Intracellular levels of GSH and MDA and antioxidant enzyme activity (SOD, CAT, and GPx) | ↑ GSH (F2; 200 μM of F3) ↓ MDA (all fractions) ↑ SOD (200 μM of F1; F2 and F3) ↑ CAT (200 μM of F1 and F2; 100 and 200 μM of F3) ↑ GPx (200 μM of F1 and F2) | [56] |

| Human intestinal (Caco-2) and liver (HepG2) cells, and LPS-stimulated murine macrophage (RAW 264.7) | Caco-2 and HepG2: 3.1, 6.3, 12.5, 25, and 50 μg/mL of whole fruit extract for 2 h RAW 264.7: 25 μg/mL of whole fruit extract for 4 h | CAA (Caco-2 and HepG2) NO secretion (RAW 264.7) | CAA (Caco-2 vs. HepG2) 9.1–29.5 vs. 26.6–40.9% ↓ NO (34.1%) | [57] |

| AAPH-induced oxidative stress in human liver cells (HepG2) | 25 μg/mL of seedless fruit extract or its 12 fractions (individually) for 20 min | Intracellular levels of ROS and inhibition of lipid peroxidation | ↓ ROS (4–27%) ↓ Lipid peroxidation (74.6–82.2%) | [58] |

| In silico study | ||||

| Molecular docking | NADPH oxidase (protein target) Polyphenols identified in seed essential oil (ligand) | Binding affinity ligand and target protein | Polyphenol with grater affinity (kcal/mol) than Trolox (–6.36): rutin (–6.99), vanillic acid (–6.62), catechin (–6.65), and p-coumaric acid (–6.07) | [37] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Santana-Farré, R.; Buset-Ríos, N.; Makran, M. Antioxidant Potential of Opuntia dillenii: A Systematic Review of Influencing Factors and Biological Efficacy. Nutraceuticals 2025, 5, 22. https://doi.org/10.3390/nutraceuticals5030022

Santana-Farré R, Buset-Ríos N, Makran M. Antioxidant Potential of Opuntia dillenii: A Systematic Review of Influencing Factors and Biological Efficacy. Nutraceuticals. 2025; 5(3):22. https://doi.org/10.3390/nutraceuticals5030022

Chicago/Turabian StyleSantana-Farré, Ruymán, Nisa Buset-Ríos, and Mussa Makran. 2025. "Antioxidant Potential of Opuntia dillenii: A Systematic Review of Influencing Factors and Biological Efficacy" Nutraceuticals 5, no. 3: 22. https://doi.org/10.3390/nutraceuticals5030022

APA StyleSantana-Farré, R., Buset-Ríos, N., & Makran, M. (2025). Antioxidant Potential of Opuntia dillenii: A Systematic Review of Influencing Factors and Biological Efficacy. Nutraceuticals, 5(3), 22. https://doi.org/10.3390/nutraceuticals5030022