Evaluation of Food Offerings for Workers in Commercial Foodservices from the Perspective of Healthiness and Sustainability

Highlights

- Examines how food insecurity, excess weight, and meal quality intersect among workers who work in food services, a population often overlooked in public health nutrition.

- Links workers’ social vulnerability, nutritional status, and menu healthiness/sustainability to broader public health challenges, including non-communicable diseases and inequities in access to adequate food.

- High food insecurity and overweight/obesity among workers, alongside menus high in lipids, sodium, and environmental impact, suggesting health risks and inequities.

- By integrating social, nutritional, and environmental indicators, the study advances understanding of how workplace food environments can support or undermine health.

- Urges practitioners to redesign menus and procurement to reduce sodium and lipids, prioritize low-impact proteins, and integrate food security and sustainability.

- Highlights for researchers the importance of multidimensional approaches for scalable monitoring tools and interventions.

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

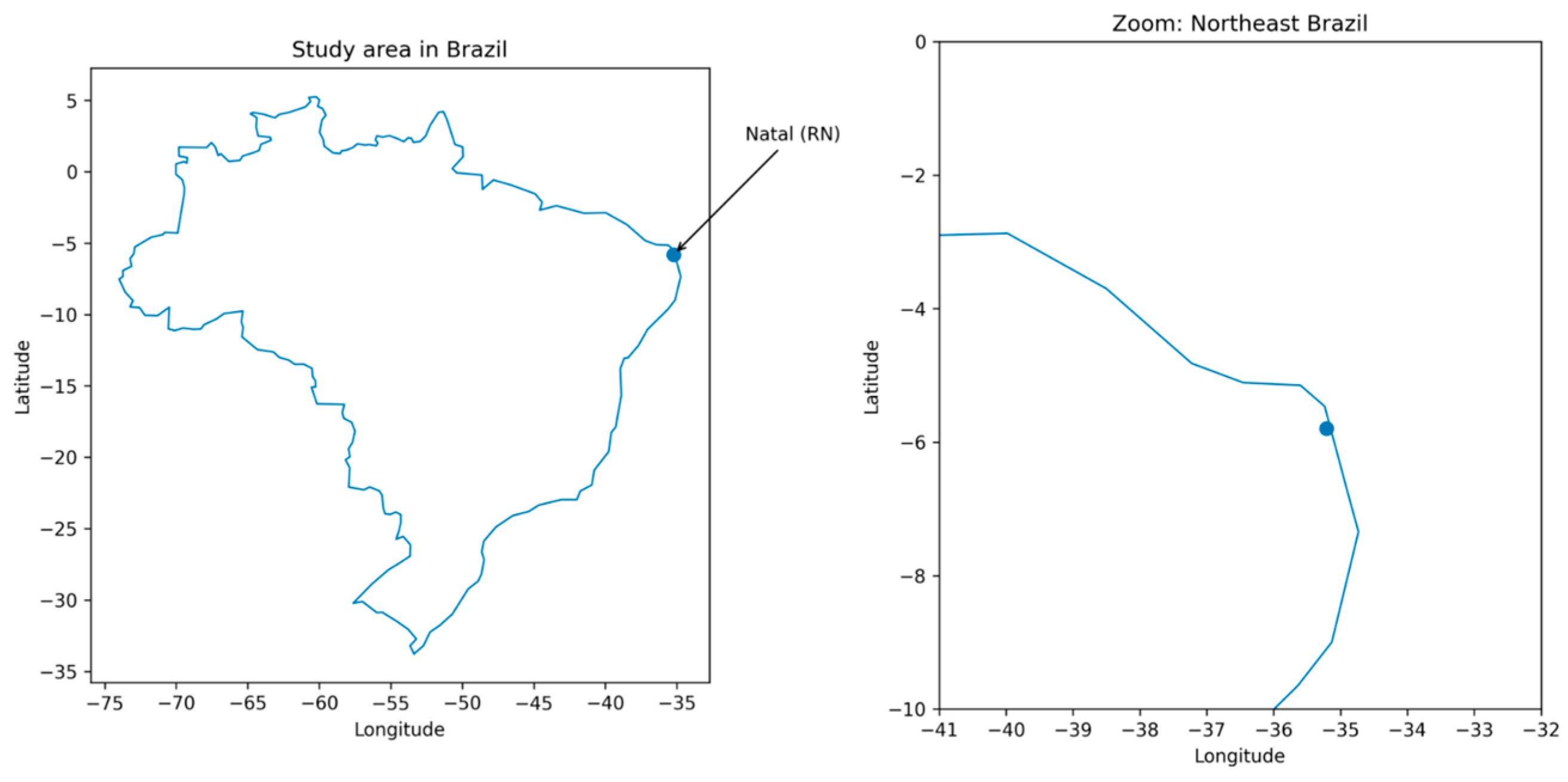

2.1. Study Design and Setting

2.2. Participants and Sampling

2.3. Data Collection Components

2.4. Social Component: Questionnaire and Food Insecurity

2.5. Health Component: Anthropometry and Nutritional Assessment

2.6. Menu Composition and Food Processing Assessment

2.7. Environmental Component: Footprints

2.8. Statistical Analysis and Data Triangulation

2.9. Ethics

3. Results

3.1. Influence of Served Meals on Food Security

3.2. Influence of Served Meals on Workers’ Health

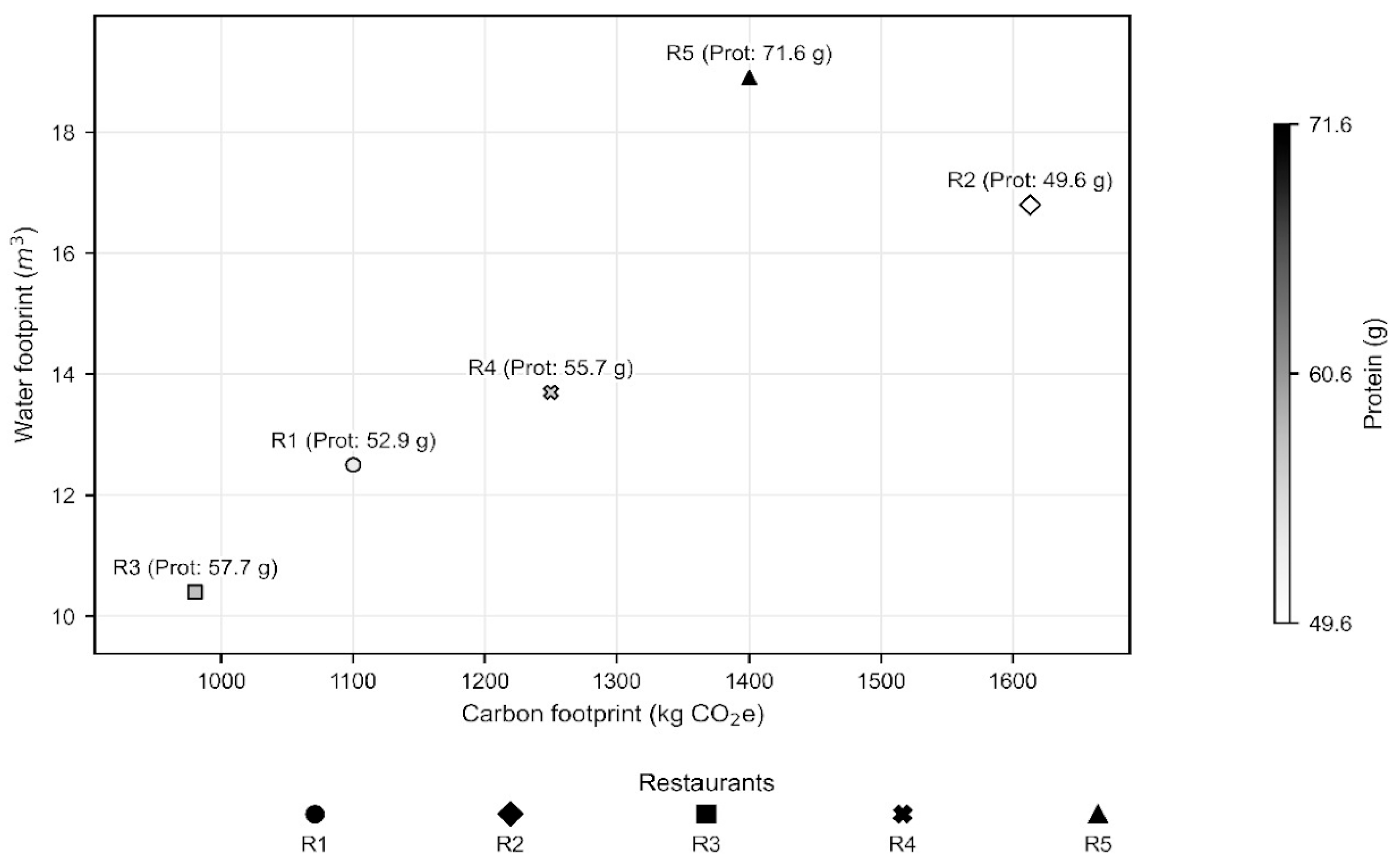

3.3. Sustainability-Related Findings Within the INSTITUTIONAL Context

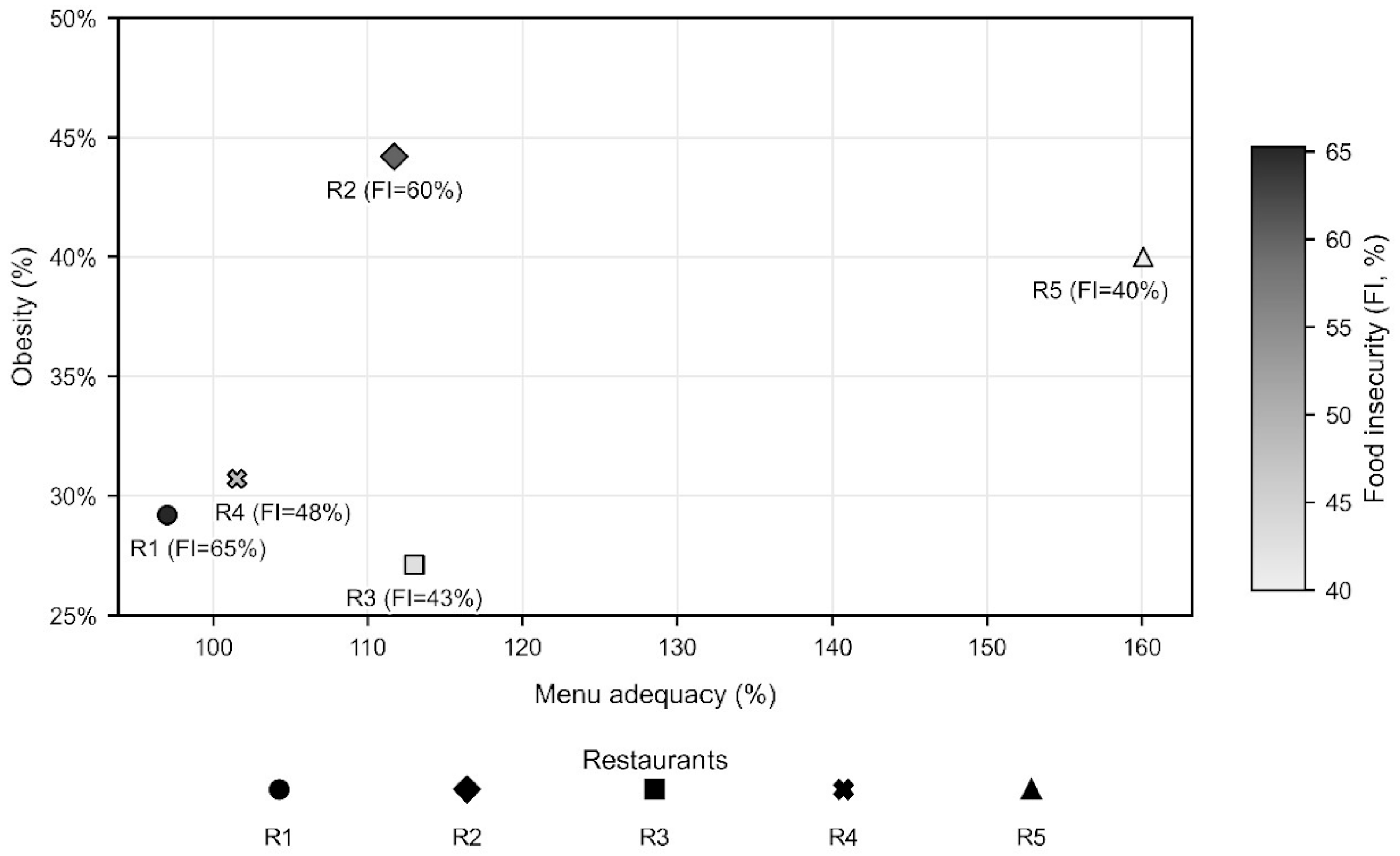

3.4. Data Triangulation Across Dimensions

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| EBIA | Brazilian Food Insecurity Scale |

| HRAF | Human Right to Adequate Food |

| FI | Food Insecurity |

| FS | Food Security |

| LOSAN | Brazilian Organic Law on Food Security |

| NCDs | Non-Communicable Diseases |

| BMI | Body Mass Index |

| SISVAN | Brazilian Food and Nutrition Surveillance System |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

| TEV | Average Total Energy Value |

| TEE | Total Energy Expenditure |

| BMR | Basal Metabolic Rate |

| PAL | Physical Activity Level |

| ILSI | Nutritional recommendations followed the International Life Sciences Institute Brazil |

| DRI | Dietary Reference Intakes |

| PAHO | Pan American Health Organization |

| CF | Carbon footprint |

| WF | Water footprint |

| EF | Ecological footprint |

| UFRN | Federal University of Rio Grande do Norte |

References

- Zhang, X.-X.; Liu, J.-S.; Han, L.-F.; Xia, S.; Li, S.-Z.; Li, O.Y.; Kassegne, K.; Li, M.; Yin, K.; Hu, Q.-Q.; et al. Towards a global One Health index: A potential assessment tool for One Health performance. Infect. Dis. Poverty 2022, 11, 125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Tripartite and UNEP support OHHLEP’s definition of “One Health.” 2021. Available online: https://www.who.int/news/item/01-12-2021-tripartite-and-unep-support-ohhlep-s-definition-of-one-health (accessed on 22 June 2025).

- Veiros, M.B.; Proença, R.P.C.P. Avaliação qualitativa das preparações do cardápio em uma unidade de alimentação e nutrição: Método AQPC. Nutr. Pauta 2003, 11, 36–42. [Google Scholar]

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations; World Health Organization. Dietas Saudáveis Sustentáveis—Princípios Orientadores; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- von Koerber, K.; Bader, N.; Leitzmann, C. Wholesome nutrition: An example for a sustainable diet. Proc. Nutr. Soc. 2017, 76, 34–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conselho Federal de Nutricionistas (CFN). Resolução n° 600/2018; CFN: Brasília, Brasil, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Abreu, E.S.; Spinelli, M.G.N.; Pinto, M. Gestão de Unidades de Alimentação e Nutrição: Um Modo de Fazer, 6th ed.; Metha: São Paulo, Brasil, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Boas, L.G.V. A Escala Brasileira de Insegurança Alimentar (EBIA) e as principais condicionantes da (in)segurança alimentar no Brasil. Geoconexões 2023, 1, 114–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brasil. Lei n° 11.346, de 15 de Setembro De 2006; Cria o Sistema Nacional de Segurança Alimentar e Nutricional; Diário Oficial da União: Brasília, Brasil, 2006.

- Balestrin, M.B.; Carlesso, L.C.; Xavier, A.A. Análise quantitativa e qualitativa do cardápio oferecido aos funcionários beneficiados pelo Programa de Alimentação do Trabalhador (PAT) em um frigorífico situado em Campos Novos—Santa Catarina. Anuário Pesqui. Extensão Unoesc Videira 2018, 3, e19228. [Google Scholar]

- De Freitas, R.S.G.; Stedefeldt, E. Food Systems Resilience: How to Build Food Safety Resilience in Commercial Restaurants; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO; IFAD; UNICEF; WFP; WHO. The State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World 2024—Financing to End Hunger, Food Insecurity and Malnutrition in All Its Forms; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO; IFAD; PAHO; UNICEF; WFP. Latin America and the Caribbean—Regional Overview of Food Security and Nutrition 2024; FAO, IFAD, PAHO, UNICEF, WFP: Santiago, Chile, 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística (IBGE). Segurança Alimentar 2024; IBGE: Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 2025; 12p. Available online: https://biblioteca.ibge.gov.br/visualizacao/livros/liv102212_informativo.pdf (accessed on 21 December 2025).

- Brasil; Ministério da Saúde. Vigilância de Doenças Não Transmissíveis: Relatório Técnico; Ministério da Saúde: Brasília, Brasil, 2020.

- Edmundo, A.S.; Pinto, E.; Baltazar, A.L.; Fialho, S.; Lima, J. Sustentabilidade alimentar em alimentação coletiva e restauração: Percepção dos nutricionistas. Acta Port. Nutr. 2022, 31, 44–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- dos Santos, L.P.; Lindemann, I.L.; Motta, J.V.d.S.; Mintem, G.; Bender, E.; Gigante, D.P. Proposta de versão curta da Escala Brasileira de Insegurança Alimentar. Rev. Saude Publica 2014, 48, 783–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coelho, S.E.d.A.C.; Vianna, R.P.d.T.; Segall-Correa, A.M.; Perez-Escamilla, R.; Gubert, M.B. Insegurança alimentar entre adolescentes brasileiros: Validação da escala curta. Rev. Nutr. 2015, 28, 385–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brasil; Ministério da Saúde. Orientações para a Coleta e Análise de Dados Antropométricos em Serviços de Saúde: SISVAN; Ministério da Saúde: Brasília, Brasil, 2011.

- World Health Organization. Physical Status: The Use and Interpretation of Anthropometry; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- FAO; WHO; UNU. Human Energy Requirements; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Dietary Reference Intakes for Sodium and Potassium; National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NEPA-UNICAMP. Tabela Brasileira de Composição de Alimentos, 4th ed.; NEPA-UNICAMP: Campinas, Brasil, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Cominetti, C.; Cozzolino, S.M.F. Recomendações de Nutrientes, 3rd ed.; ILSI Brasil: São Paulo, Brasil, 2023; ISBN 978-65-86937-18-3. [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Medicine. Dietary Reference Intakes for Energy, Carbohydrate, Fiber, Fat, Fatty Acids, Cholesterol, Protein, and Amino Acids; National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Medicine. Dietary Reference Intakes for Calcium and Vitamin D; National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Nogueira, J.P.; Hatjiathanassiadou, M.; de Souza, S.R.G.; Strasburg, V.J.; Rolim, P.M.; Seabra, L.M.J. Sustainable perspective in public educational institution restaurants: From foodstuffs purchase to meal offer. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brasil. Decreto n° 67.647, de 23 de novembro de 1970; Estabelece nova divisão regional do Brasil: Brasília, Brasil, 1970.

- Green Restaurant Association. Green Restaurant Certification 8.0 Standards. 2024. Available online: https://www.dinegreen.com/certification-standards (accessed on 13 July 2025).

- Martinelli, S.S.; Cavalli, S.B. Alimentação saudável e sustentável: Uma revisão narrativa sobre desafios e perspectivas. Cienc. Saude Coletiva 2019, 24, 4251–4261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brasil; Ministério da Saúde. Guia Alimentar Para A População Brasileira, 2nd ed.; Ministério da Saúde: Brasília, Brasil, 2014.

- Monteiro, C.A.; Cannon, G.; Levy, R.B.; Moubarac, J.C.; Jaime, P.; Martins, A.P.; Canella, D.; Louzada, M.; Parra, D.; Calixto, G. NOVA: Classificação dos alimentos. World Nutr. 2016, 7, 28–40. [Google Scholar]

- Granja, I.P.T.; Mesquita, M.C.C.; Oliveira, A.C.F.; Silva, G.G.; Carneiro, V.C.P.; Lourenção, L.F.P.; Dala-Paula, B.M. Nova Rotulagem Nutricional de Alimentos Embalados; UNIFAL-MG: Alfenas, Brasil, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Brasil; Agência Nacional de Vigilância Sanitária (ANVISA). Resolução RDC n° 429, de 8 de Outubro de 2020; ANVISA: Brasília, Brasil, 2020.

- Brasil; Agência Nacional de Vigilância Sanitária (ANVISA). Resolução RDC n° 727, de 1° de Julho de 2022; ANVISA: Brasília, Brasil, 2022.

- Organização Pan-Americana da Saúde (OPAS). Modelo de Perfil Nutricional da OPAS; OPAS: Washington, DC, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Batista, C.H.K.; Leite, F.H.M.; Borges, C.A. Associação entre padrão de publicidade e alimento ultraprocessado em pequenos mercados. Ciênc Saúde Coletiva 2022, 27, 2667–2678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garzillo, J.M.F.; Poli, V.F.S.; Leite, F.H.M.; Steele, E.M.; Machado, P.P.; Louzada, M.L.d.C.; Levy, R.B.; Monteiro, C.A. Ultra-processed food intake and diet carbon and water footprints: A national study in Brazil. Rev. de Saude Publica 2022, 56, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garzillo, J.M.F.; Machado, P.P.; Louzada, M.L.D.C.; Levy, R.B.; Monteiro, C.A. Pegadas Dos Alimentos E Das Preparações Culinárias Consumidos No Brasil; Faculdade de Saúde Pública da USP: São Paulo, Brasil, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zanin, L.M.; Luning, P.A.; da Cunha, D.T.; Stedefeldt, E. Influence of educational actions on transitioning of food safety culture in a food service context: Part 1—Triangulation and data interpretation of food safety culture elements. Food Control 2021, 119, 107447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Wide Fund for Nature (WWF). One Planet Plate 2021: Criteria and Background; WWF: Solna, Sweden, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Fideles, I.C.; Akutsu, R.d.C.C.d.A.; Barroso, R.d.R.F.; Costa-Souza, J.; Zandonadi, R.P.; Raposo, A.; Botelho, R.B.A. Food insecurity among low-income food handlers: A nationwide study in Brazilian community restaurants. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Falcão, A.C.M.L.; de Aguiar, O.B.; Fonseca, M.d.J.M.d. Association of socioeconomic, labor and health variables related to food insecurity in workers of the popular restaurants in Rio de Janeiro. Rev. Nutr. 2015, 28, 77–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coutinho, G.R.; dos Santos, S.M.C.; Gama, C.M.; da Silva, S.O.; dos Santos, M.E.P.; Silva, N.d.J. Fatores demográficos e socioambientais associados à insegurança alimentar domiciliar em Salvador, Bahia. Cad. Saúde Pública 2022, 38, e00280821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garcia, A.C.N.; Fonseca, H.d.S.; Jardim, M.Z.; Cordeiro, N.G.; Lisboa, S.C.P.; Amaral, J.H.d.S.; Costa, B.V.d.L. Condição domiciliar de (in)segurança alimentar dos trabalhadores dos bancos de alimentos. Segurança Aliment. Nutr. 2022, 29, e022022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Storz, M.A.; Rizzo, G.; Lombardo, M. Shiftwork Is Associated with Higher Food Insecurity in U.S. Workers: Findings from a Cross-Sectional Study (NHANES). Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 2847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- dos Santos, J.; Ferreira, A.A.; Meira, K.C.; Pierin, A.M.G. Excess weight in employees of food and nutrition units at a university in São Paulo State. Einstein 2013, 11, 486–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, R.M.; Bezerra, I.W.L.; Torres, K.G.; Pereira, G.S.; de Souza, A.M.; Oliveira, A.G. Participation in a food assistance program and excessive weight gain: An evaluation of the Brazilian Worker’s Food Program. BMC Public Health 2022, 22, 1125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Meira, E.; Rebequi, F.; Vaz, D.S.S.; Mazur, C.E. Diet quality, cardiovascular risk and nutritional status of workers assisted by the Worker’s Food Program. BRASPEN J. 2020, 35, 56–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrade, A.B.R.; Nabarro, M.A.; Silva, P.C.; Martha, C.M.C. Avaliação dos cardápios em uma unidade de alimentação e nutrição analisando as normas do PAT e a disponibilidade de ferro. J. Health Sci. Inst. 2022, 40, 43–48. [Google Scholar]

- de Souza, E.D.; Schneider, C.M.A.; Weis, G.C.C. Avaliação quantitativa e qualitativa do cardápio de uma unidade de alimentação e nutrição da região noroeste do Rio Grande do Sul. Discip. Sci.|Saúde 2020, 21, 127–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, E.R.d.S.; Nascimento, L.E.D.; Freitas, R.d.S.F.; De Almeida, A.P.C.; Brandão, R.N.; De Arruda, M.V.C.; Moraes, S.S.d.A.; Alves, M.A.B.d.S. Avaliação da composição nutricional de refeições oferecidas por uma uni-dade de alimentação e nutrição. Braz. J. Health Rev. 2021, 4, 24565–24574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosi, A.; Biasini, B.; Donati, M.; Ricci, C.; Scazzina, F. Adherence to the Mediterranean diet and environmental impact in schoolchildren in Parma, Italy. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 6105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dyer, J.; Worth, D.; Vergé, X.; Desjardins, R. Impact of recommended red meat consumption in Canada on the carbon footprint of livestock production. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 266, 121785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pörtner, L.M.; Schlenger, L.; Gabrysch, S.; Lambrecht, N.J. Dietary quality and environmental footprint of health-care foodser-vice: A quantitative analysis using dietary indices and lifecycle assessment data. Lancet Planet. Health 2025, 9, 101274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, J.; Oza-Frank, R.; Lowry-Warnock, A.; Williams, B.D.; Murphy, M.; Hill, A.; Silverman, J. Healthy Food Service Guide-lines for Worksites and Institutions: A Scoping Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2025, 22, 1194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Food Insecurity—N (%) | Food Security—N (%) | Total | p-Value ** | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age * | Mild FI: | Moderate FI: | Severe FI: | |||

| <24 | 20 (32.3%) | 9 (14.5%) | 4 (6.4%) | 29 (46.8%) | 62 | 0.979 |

| ≥24 | 62 (31.3%) | 19 (9.6%) | 24 (12.1%) | 93 (47.0%) | 198 | |

| Total | 138 (53.1%) | 122 (46.9%) | 260 * | |||

| Gender | ||||||

| Female | 20 (27.03%) | 7 (9.46%) | 7 (9.46%) | 40 (54.1%) | 74 | 0.136 |

| Male | 63 (33.69%) | 21 (11.23%) | 21 (11.23%) | 82 (43.9%) | 187 | |

| Total | 139 (53.3%) | 122 (46.7%) | 261 | |||

| Marital status | ||||||

| With partner | 41 (33.06%) | 15 (12.1%) | 12 (9.68%) | 56 (45.2%) | 124 | 0.626 |

| Without partner | 42 (30.66%) | 13 (9.49%) | 16 (11.68%) | 66 (48.2%) | 137 | |

| Total | 139 (53.3%) | 122 (46.7%) | 261 | |||

| Race/ethnicity | ||||||

| White/Asian | 27 (28.13%) | 12 (12.5%) | 7 (7.29%) | 50 (52.1%) | 96 | 0.187 |

| Brown/Black/Indigenous | 56 (33.94%) | 16 (9.7%) | 21 (12.73%) | 72 (43.6%) | 165 | |

| Total | 139 (53.3%) | 122 (46.7%) | 261 | |||

| Municipality of residence | ||||||

| Other | 19 (38.78%) | 6 (12.24%) | 8 (16.33%) | 16 (32.7%) | 49 | 0.028 |

| Natal/Parnamirim-RN-Brazil | 64 (30.19%) | 22 (10.38%) | 20 (9.43%) | 106 (50.0%) | 212 | |

| Total | 139 (53.3%) | 122 (46.7%) | 261 | |||

| Household size | ||||||

| Up to 2 people | 25 (28.41%) | 3 (3.41%) | 10 (11.36%) | 50 (56.8%) | 88 | 0.020 |

| More than 2 people | 58 (33.53%) | 25 (14.45%) | 18 (10.4%) | 72 (41.6%) | 173 | |

| Total | 139 (53.3%) | 122 (46.7%) | 261 | |||

| Monthly income * | ||||||

| ≤R$ 2824.00 | 44 (33.33%) | 17 (12.88%) | 21 (15.91%) | 50 (37.9%) | 132 | 0.001 |

| >R$ 2824.00 | 28 (27.72%) | 8 (7.92%) | 5 (4.95%) | 60 (59.4%) | 101 | |

| Total | 123 (52.8%) | 110 (47.2%) | 233 * | |||

| Education level * | ||||||

| Elementary or high school | 69 (33.01%) | 25 (11.96%) | 25 (11.96%) | 90 (43.1%) | 209 | 0.023 |

| Higher education or postgraduate | 14 (27.45%) | 3 (5.88%) | 3 (5.88%) | 31 (60.8%) | 51 | |

| Total | 139 (53.5%) | 121 (46.5%) | 260 * | |||

| Job type | ||||||

| Base position | 53 (29.94%) | 25 (14.12%) | 22 (12.43%) | 77 (43.5%) | 177 | 0.128 |

| Technical/superior | 30 (35.71%) | 3 (3.57%) | 6 (7.14%) | 45 (53.6%) | 84 | |

| Total | 139 (53.3%) | 122 (46.7%) | 261 | |||

| Occupational sector | ||||||

| Administrative | 9 (31.03%) | 1 (3.45%) | 1 (3.45%) | 18 (62.1%) | 29 | 0.079 |

| Operational | 74 (31.9%) | 27 (11.64%) | 27 (11.64%) | 104 (44.8%) | 232 | |

| Total | 139 (53.3%) | 122 (46.7%) | 261 | |||

| Job position type | ||||||

| Operational/base position | 64 (33.33%) | 22 (11.46%) | 26 (13.54%) | 80 (41.7%) | 192 | 0.006 |

| Technical/managerial position | 19 (27.54%) | 6 (8.7%) | 2 (2.9%) | 42 (60.9%) | 69 | |

| Total | 139 (53.3%) | 122 (46.7%) | 261 | |||

| Responsible for purchasing food at home | ||||||

| No | 29 (35.37%) | 7 (8.54%) | 4 (4.88%) | 42 (51.2%) | 82 | 0.327 |

| Yes | 54 (30.17%) | 21 (11.73%) | 24 (13.41%) | 80 (44.7%) | 179 | |

| Total | 139 (53.3%) | 122 (46.7%) | 261 | |||

| Participates in meal preparation at home | ||||||

| No | 22 (31.88%) | 4 (5.8%) | 6 (8.7%) | 37 (53.6%) | 69 | 0.182 |

| Yes | 61 (31.77%) | 24 (12.5%) | 22 (11.46%) | 85 (44.3%) | 192 | |

| Total | 139 (53.3%) | 122 (46.7%) | 261 | |||

| Rest. | EBIA | Anthropometry | Menu Adequacy | Environmental Footprints (Monthly Mean) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CF kgCO2 | WF m3 | EF kgm2 | |||||||

| R1 | Food Insecurity Levels | BMI classification | Adequacy: | 97% | 1613 | 1483 | 7.6 | ||

| Severe FI: | 13.7% | Underweight: | 1.8% | Protein (g) | 52.9 | ||||

| Mild FI: | 36.8% | Normal weight: | 38.1% | Lipids (g) | 35.9 | ||||

| Moderate FI: | 14.7% | Overweight: | 31.0% | Carbohydrates (g) | 85.4 | ||||

| FS: | 34.7% | Obesity I–III: | 29.2% | Sodium (mg) | 1156 | ||||

| R2 | Food Insecurity Levels | BMI classification | Adequacy: | 112% | 1479 | 1385 | 6.0 | ||

| Severe FI: | 13.3% | Underweight: | 2.3% | Protein (g) | 49.6 | ||||

| Mild FI: | 40.0% | Normal weight: | 18.6% | Lipids (g) | 44.4 | ||||

| Moderate FI: | 6.7% | Overweight: | 34.9% | Carbohydrates (g) | 85.9 | ||||

| FS: | 40.0% | Obesity I–III: | 44.2% | Sodium (mg) | 1493 | ||||

| R3 | Food Insecurity Levels | BMI classification | Adequacy: | 113% | 2835 | 2458 | 14.0 | ||

| Severe FI: | 4.5% | Underweight: | 0.0% | Protein (g) | 57.7 | ||||

| Mild FI: | 29.2% | Normal weight: | 39.0% | Lipids (g) | 41.7 | ||||

| Moderate FI: | 9.0% | Overweight: | 33.9% | Carbohydrates (g) | 99.1 | ||||

| FS: | 57.3% | Obesity I–III: | 27.1% | Sodium (mg) | 950 | ||||

| R4 | Food Insecurity Levels | BMI classification | Adequacy: | 102% | 3411 | 2607 | 21.0 | ||

| Severe FI: | 17.4% | Underweight: | 1.6% | Protein (g) | 55.7 | ||||

| Mild FI: | 21.7% | Normal weight: | 29.1% | Lipids (g) | 37.6 | ||||

| Moderate FI: | 8.7% | Overweight: | 38.6% | Carbohydrates (g) | 95.1 | ||||

| FS: | 52.2% | Obesity I–III: | 30.7% | Sodium (mg) | 1487 | ||||

| R5 | Food Insecurity Levels | BMI classification | Adequacy: | 160% | 2170 | 1806 | 14.0 | ||

| Severe FI: | 12.0% | Underweight: | 1.1% | Protein (g) | 71.6 | ||||

| Mild FI: | 20.0% | Normal weight: | 22.1% | Lipids (g) | 58.8 | ||||

| Moderate FI: | 8.0% | Overweight: | 36.8% | Carbohydrates (g) | 128.5 | ||||

| FS: | 60.0% | Obesity I–III: | 40.0% | Sodium (mg) | 2242 | ||||

| Average environmental footprints across restaurant | 2302 | 1.95 | 12.52 | ||||||

| Food Group | CF (kg CO2e) | WF (m3) | EF (kg·m2) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Beef | 3685.95 a | 2599.19 a | 12.72 a |

| Poultry and eggs | 573.45 b | 729.09 b | 0.43 ab |

| Pork | 814.66 b | 864.68 b | 0.33 b |

| Fish and seafood | 593.62 b | 14.10 bc | 25.83 b |

| Dairy products | 74.04 c | 54.88 c | 0.06 c |

| Fruits and vegetables | 28.02 d | 52.37 d | 0.02 d |

| Cereals, legumes, and pasta | 46.01 d | 70.61 d | 0.03 d |

| Others | 53.72 d | 48.66 d | 0.05 d |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Marinho, T.d.G.S.; Faustino, M.L.M.; Silva, M.I.d.O.; Santos, T.d.G.; Bezerra, I.W.L.; Rolim, P.M. Evaluation of Food Offerings for Workers in Commercial Foodservices from the Perspective of Healthiness and Sustainability. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2026, 23, 71. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph23010071

Marinho TdGS, Faustino MLM, Silva MIdO, Santos TdG, Bezerra IWL, Rolim PM. Evaluation of Food Offerings for Workers in Commercial Foodservices from the Perspective of Healthiness and Sustainability. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2026; 23(1):71. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph23010071

Chicago/Turabian StyleMarinho, Thaís de Gois Santos, Maria Luísa Meira Faustino, Maria Izabel de Oliveira Silva, Tatiane de Gois Santos, Ingrid Wilza Leal Bezerra, and Priscilla Moura Rolim. 2026. "Evaluation of Food Offerings for Workers in Commercial Foodservices from the Perspective of Healthiness and Sustainability" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 23, no. 1: 71. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph23010071

APA StyleMarinho, T. d. G. S., Faustino, M. L. M., Silva, M. I. d. O., Santos, T. d. G., Bezerra, I. W. L., & Rolim, P. M. (2026). Evaluation of Food Offerings for Workers in Commercial Foodservices from the Perspective of Healthiness and Sustainability. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 23(1), 71. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph23010071