Culturally Adapted Mental Health Education Programs for Migrant Populations: A Scoping Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

- To map the scope and characteristics of existing MHE programs, including target populations, settings, and types of interventions.

- To identify the range of cultural adaptation strategies employed across programs.

- To examine reported program outcomes and evaluation findings.

2. Method

2.1. Design

- What types of cultural adaptation strategies are employed in these programs (including language modifications, delivery models, integration of cultural values, and traditional healing practices)?

- What are the key components, theoretical frameworks, and delivery approaches of culturally responsive programs?

- What outcomes and evidence of effectiveness have been reported across different migrant populations and settings?

2.2. Search Strategy

- Population: Immigrants, migrants, refugees, asylum seekers, and undocumented migrants.

- Concept: Mental health education (to capture diverse expressions of mental health literacy programming including psychoeducation and mental health skills building).

- Context: Cultural adaptation strategies, including culturally safe, culturally sensitive, and culturally adapted delivery approaches, as well as traditional and complementary healing practices (traditional medicine, spiritual healing, faith-based approaches, complementary therapies).

2.3. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

- Focused on migrants (including refugees, immigrants, undocumented migrants, and asylum seekers).

- Described mental health education programs, including psychoeducation, mental health literacy, mental health awareness, and skill-building.

- Demonstrated cultural adaptation or cultural responsiveness through one or more of the following approaches: a. language translation or bilingual delivery; b. culturally adapted content (e.g., metaphors, or case vignettes); c. incorporation of cultural values, beliefs, or worldviews; d. community-based, peer-led, or culturally matched delivery models; e. use of cultural idioms of distress or local mental health terminology; f. integration of traditional medicine, complementary healing practices, spiritual approaches, or faith-based healing.

- Were conducted in migrant-receiving countries.

- Were published in English.

- Focused on populations other than migrants.

- Addressed physical health without mental health as a central focus.

- Focused solely on clinical interventions without any mental health awareness, psychoeducation, or skill-building elements.

- Did not demonstrate any form of cultural adaptation, cultural tailoring, or cultural responsiveness to migrant populations.

- Were non-peer reviewed publications (e.g., book chapters).

2.4. Screening Process and Data Extraction

2.5. Charting the Data

2.6. Collating, Summarizing and Reporting the Results

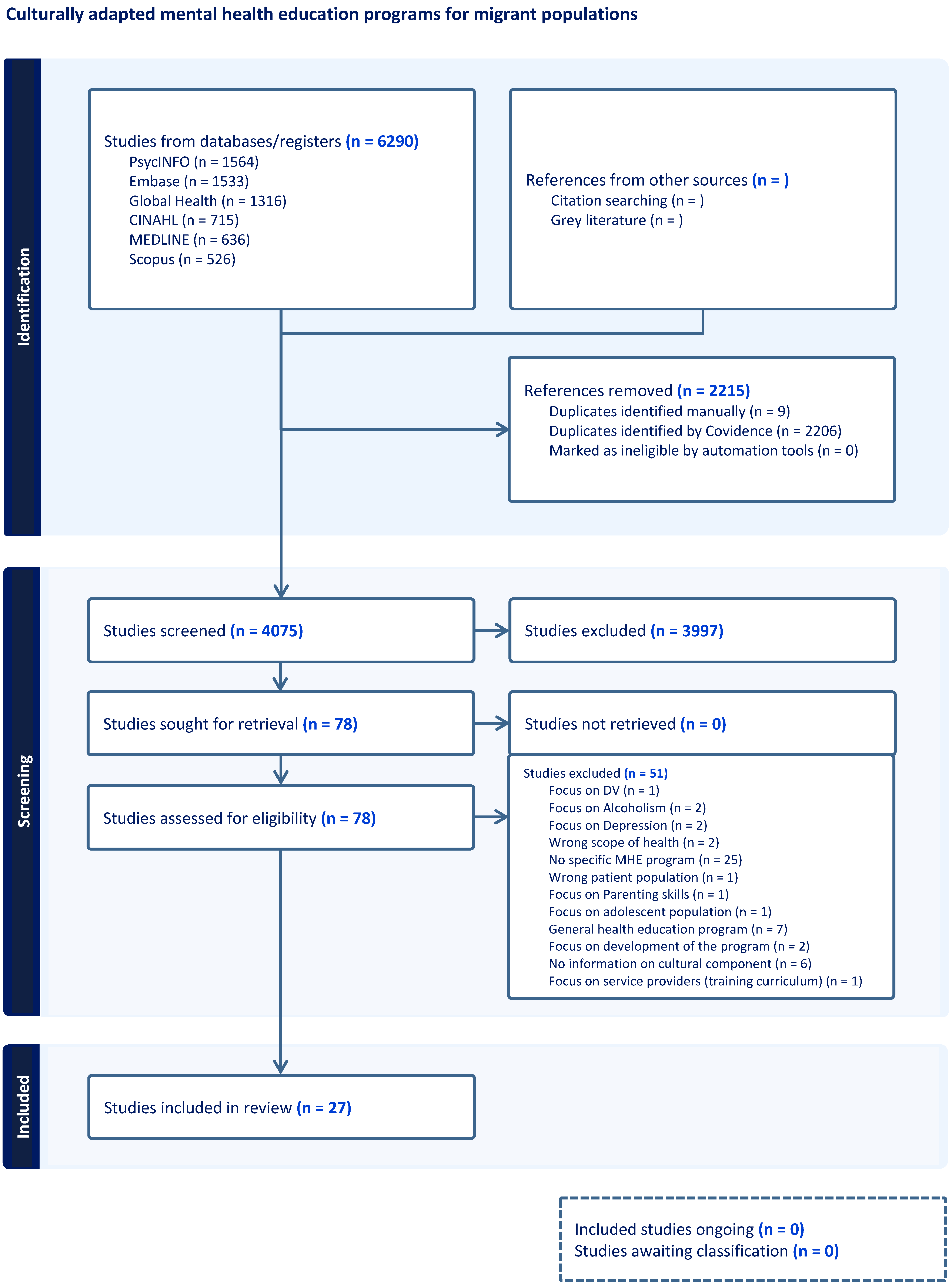

3. Results

3.1. Key Characteristics of Studies

3.2. Population and Program Characteristics

3.3. Program Structure and Delivery Modalities

3.4. Program Content and Focus Areas

3.5. Theoretical Frameworks and Approaches Used in Programs

3.6. Cultural Adaptations and Traditional Knowledge Integration in Programs

3.7. Program Outcomes and Effectiveness

3.8. Program Implementation Challenges and Facilitators

3.9. Key Features of Culturally Adapted Mental Health Education Programs

3.9.1. Cultural Adaptation and Sensitivity

3.9.2. Addressing Unique Migration-Related Stressors and Challenges

3.9.3. Integration of Traditional and Western Approaches

3.9.4. Theoretical Frameworks and Evidence-Based Practices

3.9.5. Evaluation Methodologies

3.9.6. Application of Holistic Frameworks

3.9.7. Community-Based Peer Support Models

4. Discussion

4.1. Limitations and Implications for Research and Practice

4.2. Recommendations for Practice and Policy

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| MHE | Mental health education |

| RCT | Randomized controlled trials |

| CBPR | Community-based participatory research |

| PTSD | Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder |

| PCC | Population–Concept–Context |

| CBT | Cognitive–Behavioral Therapy |

| PRISMA-ScR | Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for Scoping Reviews |

| LGBTQ+ | Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, Queer/Questioning, and others |

Appendix A. Search Strategy

Example Search Strategy

- exp “Emigrants and Immigrants”/or (immigrant* or immigration* or emigrant* or emigration* or incomer* or “in comer*” or “new comer*” or newcomer* or resettler* or “foreign born” or refugee* or “asylum seek*” or migrant*).mp. 91906

- Mental Health/ed [Education] 490

- mental health/and (education/ or teaching/) 438

- exp Mental Disorders/ed [Education] 22

- Mental Disorders/and (education/ or teaching/) 975

- exp anxiety disorders/ed or exp obsessive-compulsive disorder/ed or exp phobic disorders/ed or exp “disruptive, impulse control, and conduct disorders”/ed or exp dissociative disorders/ed or exp mood disorders/ed or exp “bipolar and related disorders”/ed or exp depressive disorder/ed or exp personality disorders/ed or exp “schizophrenia spectrum and other psychotic disorders”/ed or exp psychotic disorders/ed or exp schizophrenia/ed or exp substance-related disorders/ed or exp alcohol-related disorders/ed or exp narcotic-related disorders/ed or exp “trauma and stressor related disorders”/ed or exp stress disorders, traumatic/ed or exp psychological trauma/ed or exp sexual trauma/ed 17

- (Mental Health/ or exp Mental Disorders/ or exp anxiety disorders/ or exp obsessive-compulsive disorder/ or exp phobic disorders/ or exp “disruptive, impulse control, and conduct disorders”/ or exp dissociative disorders/ or exp mood disorders/ or exp “bipolar and related disorders”/ or exp depressive disorder/ or exp personality disorders/ or exp “schizophrenia spectrum and other psychotic disorders”/ or exp psychotic disorders/ or exp schizophrenia/ or exp substance-related disorders/ or exp alcohol-related disorders/ or exp narcotic-related disorders/ or exp “trauma and stressor related disorders”/ or exp stress disorders, traumatic/ or exp psychological trauma/ or exp sexual trauma/) and (educat* or teach* or learn* or literacy or literat* or school* or instruction* or guidance or train*).ab. 254397

- ((“mental* health*” or “mental wellbeing” or “mental wellness” or “mental* ill*” or “mental disorder*” or “psychological health” or “psychological wellbeing” or “psychological wellness” or “psychological* ill*” or “psychological* disorder*” or “psychiatric illness*” or “psychiatric disorder*” or “psychiatric health” or “psychotic disorder*” or “psychotic condition*” or anxiety or phobia* or phobic or “panic disorder*” or “obsessive compulsive disorder*” or OCD or “stress disorder” or PTSD or “behavio?r disorder*” or “emotion* disorder*” or “oppositional defiant disorder” or ODD or “conduct disorder” or CD or “attention deficit hyperactivity disorder” or ADHD or bipolar or mania or manic or depression or depressive or psychotic or “mood disorder*” or suicid* or dissociative or dissociation or “depersonali?ation disorder” or “eating disorder*” or anorexi* or bulimi* or “binge eat*” or paranoia or paranoid or “personality disorder*” or schizophreni* or psychosis or “dysmorphic disorder*” or “self harm*” or “self mutilat*”) adj4 (educat* or teach* or learn* or inform* or literacy or literat* or school* or instruction* or guidance or prepar* or train*)).mp. 58807

- ((grief or griev* or trauma) adj4 (educat* or teach* or learn* or inform* or literacy or literat* or school* or instruction* or guidance or prepar* or train*)).mp. 9263

- or/2-9 299520

- Cultural Competency/ 6635

- exp cultural diversity/ 13325

- ((cultur* adj3 (safe* or competen* or sensitiv* or appropriate* or specific or background* or adapt* or perspective* or experienc* or group* or identity or influenc* or tailor* or suitabl* or relevan* or conscious* or pluralism or divers*)) or transcultur* or multicultur* or multi-cultur* or crosscultur* or cross-cultur* or pluralism).mp. 149989

- exp Complementary Therapies/ or (((aroma or art or “Bach flower” or bioelectromagnetic or biofield or bioresonance or chelation or colo?r or complementary or craniosacral or cupping or dance or horticultural or laughter or “mind body” or music or play or relaxation or sensory or soft tissue or spiritual or traditional or “trigger point” or touch or visualization) adj2 therap*) or (medicine* adj2 (complementary or alternative or integrative or traditional or functional or arabic or unani or ayurvedic or kampo or kanpo or Siddha or Tibetan or Mongolian or Chinese)) or acupressure or acupuncture or “autogenic training” or autosuggestion or anthroposophy or auriculotherapy or aromatherapy or biofeedback or “breathing exercises” or electroacupuncture or “diffuse noxious inhibitory control” or “faith healing” or herbalism or “historical eclecticism” or “holistic health” or homeopathy or integrative oncology or iridology or hypnosis or magic or ((musculoskeletal or osteopathic or chiropractic* or kinesiology) adj3 manipulations) or meditation or “mental healing” or meridians or mesotherapy or mindfulness or moxibustion or “manual lymphatic drainage” or naturopathy or neurofeedback or organotherapy or psychodrama or psychophysiology or phytotherapy or prolotherapy or qigong or reflexotherapy or reiki or radiesthesia or “role playing” or rolfing or seitai or shamani* or shiatsu or speleotherapy or “soul retrieval” or (traditional adj2 complementary) or (complementary adj2 alternative) or TCM or “tai ji” or “tai chi” or “therapeutic touch” or visualisation or yoga or witchcraft or “way? of knowing”).mp. 417776

- ((linguistic* or language* or religious* or faith* or religion*) adj3 (safe* or competen* or sensitiv* or appropriate* or specific or background* or adapt* or perspective* or experienc* or group* or identity or influenc* or tailor* or suitabl* or relevan* or conscious* or pluralism or divers*)).mp. 29697

- or/11-15 586349

- 1 and 10 and 16 636

Appendix B

| Article | Population | MHE Program | Program Content/Framework | Cultural Adaptation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Akhtar et al. (2021) [17] | Syrian refugees in camps and urban settings in Turkey | Group Problem Management Plus (PM+) | Psycho-educational program focusing on stress management, problem management, behavioral activation, social support strengthening | Arabic/Turkish; culturally adapted content, metaphors and illustrations; family engagement sessions; Arab facilitators; aligned with cultural values (family, religion, collective support) |

| Alvarez et al. (2024) [80] | Latina migrant population in US with ACEs. | Cuidándome (Self-Care) | 9-module psycho-educational curriculum adapted from the DECIDE program teaching problem-solving for chronic disease self-management | Translated materials to Spanish; Used culturally relevant vignettes and examples. |

| Bentley et al. (2021) [39] | Muslim refugees from Islamic countries | Islamic Trauma Healing | Integrates empirically supported PTSD treatment components with Islamic principles and practices (e.g., narratives of prophets who experienced trauma | Developed collaboratively with Somali community members and Islamic leaders; Incorporates Islamic principles, practices and prophet narratives from Quran |

| Chow et al. (2010) [18] | Chinese and Tamil clients suffering from severe mental illness and their family members. | Multi-Family Psycho-education Group (MFPG) | Designed to teach families coping and problem-solving skills, increase knowledge about mental illness, and develop a support network, based on evidence that family interventions are critical for treatment of schizophrenia | Content modified to address culturally relevant issues like stigma, concerns about long-term medication use, etc. Conducted in participants’ native languages (Chinese, Tamil). |

| Ekblad (2020) [19] | New-comer, war exposed, low-educated Arabic/Somalian-speaking middle-aged mothers | Culturally relevant tailor-made group health promotion intervention. | Silove’s (1999) Adaptation and Development After Persecution and Trauma (ADAPT) | Tailored to cultural backgrounds of participants Conducted in participants’ native languages with interpreters. |

| Garabiles et al. (2019) [81] | Overseas Filipino workers (OFWs) | World Health Organization’s Step-by-Step program (e-mental health program). | A minimally guided self-help program, wherein a nonspecialist e-Helper provides technical support and assistance in accomplishing program activities through phone calls or text messaging for up to 20 min a week | Filipino values such as bayanihan (working together to help someone) and utang-na-loob (debt of gratitude) incorporated in the program stories and content. Characters’ personalities represented desirable Filipino values of family-orientation, warmth, care for others, sociability, and positive thinking. |

| Uribe Guajardo et al. (2018) [82] | Community-workers assisting Iraqi refugees on their resettlement | Mental Health Literacy Course adapted from the Mental Health First Aid training | Common mental illnesses, risk factors, barriers to help-seeking, and early intervention; Psychoeducation on depression, anxiety, and PTSD; Mental Health First Aid Action Plan | Culturally adapted resources on Iraqi patriarchal society, gender-specific communication barriers, and vignettes depicting Iraqi refugees with PTSD and depression for assessment |

| Gurung et al. (2020) [83] | Bhutanese refugees in the United States | Mental Health First Aid (MHFA) training | MHFA curriculum on mental illnesses (depression, anxiety, trauma, psychosis, substance use); 5-Step action plan for crisis intervention—(1) Assess the risk of suicide or harm, (2) Listen nonjudgmentally, (3) Give reassurance and information, (4) Encourage appropriate professional help, and (5) Encourage self-help and other support strategies | Bilingual English/Nepali delivery; Bhutanese trainer-led orientation; adapted case vignettes reflecting refugee experiences and migration stressors |

| Hendriks et al. (2024) [84] | Adult Arabic speaking refugees residing at asylum centers or municipalities in the Netherlands | BAMBOO—A culturally sensitive, strengths-based intervention | Positive psychology topics: strengths, emotions, relationships, gratitude, self-esteem; activities include art, meditation, goal setting | Surface adaptations: multilingual materials (in 6 languages), culturally appropriate images, local proverbs, symbol-based workbooks. Deep adaptations: Islamic principles, collectivistic values, gender-separated groups, movement-based exercises, interpreters, culturally framed stigma reduction |

| Hernandez & Organista (2013) [85] | Immigrant Latinas at risk for mental health concerns. | A Spanish-language fotonovela titled “Secret Feelings” | Fotonovela (entertainment–education) depicting Latina mother with depression; addresses symptoms, treatment options, stigma, and models help-seeking behaviors. | Fotonovela format; Spanish delivery by promotoras; culturally familiar group reading activities |

| Im et al. (2018) [36] | Somali refugees in Kenya and Somali community youth leaders in their mid-teens and early thirties. | Trauma-Informed Psychoeducation (TIPE) | Trauma psychoeducation including impacts of trauma (body, mind, relationships, spirituality); psychosocial competencies (coping, problem-solving, conflict management); Somali mental health terminology | Developed through collaboration with local Somali community organization; Peer-led by trained Somali youth leaders, assisted by community health counselors; applies cultural idioms of distress (welwel, murug, qaracan) |

| Im & Swan (2022) [35] | Refugee population | Interactive Training for Cross-Cultural Trauma-Informed Care (CC-TIC) | Trauma-sensitive curriculum covering refugee trauma, mental health issues, coping skills, cultural beliefs, acculturation stress; adapted from SAMHSA trauma guidelines | Cultural idioms of distress; mental health beliefs; community leader perspectives; acculturation stress. |

| Kiropoulos et al. (2011) [27] | CALD adult population in Australia. Study participants: Gr. | Multicultural Information on Depression Online (MIDonline) | Psychoeducation on depression: symptoms, case studies, diagnosis of depression, treatment options, finding bilingual professionals, stigma related to mental illness, and multilingual resources. | Program content in Greek, Italian, and English; Culturally relevant case studies representative of the target population |

| Koch et al. (2020) [23] | Young male Afghan refugees | Skills-Training of Affect Regulation–A Culture-sensitive Approach (STARC) | Transdiagnostic intervention focusing on emotion regulation: identifying emotions, regulation strategies (behavioral, cognitive, physiological), managing anger/sadness/anxiety | Incorporates cultural modifications to enhance program acceptability and effectiveness |

| Martinez et al. (2024) [21] | Filipino migrant domestic workers in the United Kingdom (UK). | Online mental health literacy (MHL) program called ‘Tara, Usap Tayo!’ (C’mon, Let’s Talk) | Psychoeducation curriculum based on content from WHO’s mhGAP, PM+, and the UK’s Adult IAPT, tailored and translated into Filipino. | Linguistically and culturally adapted for Filipino migrant domestic workers; integrates cultural values, beliefs, narratives, and language. |

| Morales et al. (2022) [24] | DACA (Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals) recipients, undocumented immigrants, community leaders/organizers, mental health providers serving undocumented populations | Web-based tele-mentoring: “Strengthening Everyday Life Skills of DACA Recipients and Mixed-Status Families to Heal from Painful Emotions and Distress” | MHE focused on—Emotion regulation (mastery, coping, self-care) and distress tolerance (ACCEPTS, self-soothing, radical acceptance). | Program delivered via the Extension for Community Healthcare Outcomes (ECHO) DBT adapted with Latinx cultural values (familismo, personalismo, respeto, fatalismo); integrated dichos, spiritual practices, cultural foods, songs |

| Nogueira & Schmidt (2022) [22] | Latino immigrants | Project Esperanza: Mental health workshops | Mental health literacy topics: stigma, wellness, technology/cyberbullying, anxiety, depression, self-injury, suicide prevention, children’s and men’s mental health; focus on prevention and stigma reduction | Popular Education framework (Freire): Community stakeholder collaboration (practitioners, advocates, church staff, parents); co-creation of knowledge based on lived experiences; validates community strengths, wisdom, resilience |

| Omidian (2012) [30] | Afghan refugee teachers, their families and students | A psychosocial wellness training project | Psychosocial wellness, resilience, stress/emotion coping contextualized in Afghan culture; Gendlin’s focusing technique; children’s emotional development; balance of blessings | The activities were rooted in Afghani cultural elements (traditions, metaphors, poetry, Islamic texts); included collaborative workshops identifying indigenous wellness markers and coping mechanisms, Islamic values and texts |

| Ornelas et al. (2022) [86] | Spanish speaking immigrant Latina women | Amigas Latinas Motivando el Alma (ALMA) | Mindfulness-based curriculum (breath awareness, body scans, movement); emotional awareness and self-compassion; emphasis on social support and interconnectedness | Spanish delivery; Latino music, food, potluck meals, traditions, dichos; community co-developed; illustrated booklet by Latina immigrant artist; emphasized social support and interconnectedness |

| Poudel-Tandukar et al. (2021) [37] | Resettled Bhutanese adults aged 18 or older living in Western Massachusetts | Social and Emotional Well-being (SEW) intervention | Stress and coping theory (Lazarus & Folkman) and self-efficacy theory (Bandura); 5 weekly family sessions (health education, problem-solving, breathing, yoga); modules on stress management, communication, social networking, problem-solving, healthy family environment | Peer led by Bhutanese community interventionists; family-centered approach with daily home practice; culturally tailored health education and activities |

| Sabri et al. (2021) [26] | Immigrant women survivors of cumulative trauma. | Being Safe, Healthy, and Positively Empowered (BSHAPE) | Biopsychosocial and trauma-informed empowerment models; remote individual intervention via online platform and phone; strengths-based assessment, personalized modules (sexual/reproductive health, relationships, immigration, HIV/STIs, career, finance), 4-week mindfulness phone sessions, safety planning, resource linkage | Culturally grounded and Designed for Black immigrant women |

| Slewa-Younan et al. (2020) [31] | Arabic-speaking religious and community leaders in Southwestern Sydney working with refugee communities | Mental health literacy (MHL) training workshop tailored for Arabic-speaking religious and community leaders. | Mental health literacy workshop: recognition of refugee mental health issues, Australian treatment approaches, stigma reduction, role of leaders in help-seeking promotion | Arabic delivery; integrated Western treatment approaches with culturally/religiously informed practices (spiritual guidance, prayer); designed to complement religious/community leader roles |

| Slewa-Younan et al. (2020b) [33] | Arabic-speaking resettled refugees in Sydney with high distress levels | MHL program | MHL; wellbeing concepts, common mental disorders in refugees, Australian mental health system, self-help strategies (mindfulness, relaxation) | Arabic delivery by bilingual health educators/clinicians; culturally tailored content for refugee populations |

| Tol et al. (2018) [34] | South Sudanese refugees in northern Uganda | Self-Help Plus (SH+)—a guided self-help intervention developed by WHO | Self-Help Plus (SH+/WHO): based on principles of Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT); stress management, problem-solving, behavioral activation, social support strengthening | Translated to Juba Arabic; culturally adapted language, metaphors, illustrations based on cognitive interviewing |

| Tran et al. (2014) [40] | Latino immigrants in US | ALMA (Amigas Latinas Motivando el Alma/Latina Friends Motivating the Soul), | Prevention-focused MHE focusing on- Mindfulness, self-compassion, stress/coping, social support strengthening | Spanish delivery; Latino music, food, art, migration stories, traditions; promotora-led; culturally tailored curriculum emphasizing social support and cultural connection |

| Uygun et al. (2020) [87] | Arabic-speaking adult Syrian refugees with high psychological distress in Turkey | Group Problem Management Plus (PM+) | Group Problem Management Plus (PM+): brief trans-diagnostic CBT-based psycho-edcuation; stress management, problem-solving, behavioral activation, social support strengthening | Culturally adapted for Syrian refugees; Arabic-speaking peer refugee facilitators; gender-matched groups |

| Weise et al. (2021) [88] | Adult asylum seekers in Germany experiencing mental distress. | The Tea Garden (TG) | Transdiagnostic psychoeducation: 4 modules covering trust-building, mental disorder symptoms, resources/self-care, treatment options | Native language delivery; gender-homogenous and language-homogenous groups; culturally relevant images, symbols, metaphors from participants’ backgrounds (nature, agriculture); body and animal analogies; interpreter support |

| Xin et al. (2011) [89] | Multiethnic adult refugee population. | Happy, Happy Community | Mental health promotion based on PRECEDE–PROCEED planning model; Health Belief Model (HBM); Social Support and Social Network Theory: 6 workshops on mental disorders/beliefs, acculturation, stress management, interpersonal relationships, job development, community safety; 12 support group discussions; depression screening; counseling referrals | Interpreters/cultural brokers with immigrant/refugee backgrounds; community-based needs assessment; culturally appropriate incentives (settlement resources); collaboration with similar programs; public health-social work partnership |

Appendix C

| Grey Literature | Population | MHE Program | Program Content/Framework | Cultural Adaptation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| World Health Organization (WHO) (WHO, 2021, 2024) [28,29] | Populations affected by adversity | SELF-HELP PLUS (SH+) | Stress management program based on the principles of acceptance and commitment therapy | The program may be adapted to be used in different cultural contexts. |

| Hebrew Immigrant Aid Society (HIAS) (HIAS, 2021) [38] | Refugee and newcomers in the US | HIAS Mental Health and Psychosocial-support (MHPSS) Curriculum | Content includes Psychological first aid, cultural adjustment, family and community resilience. 9-week support group sessions, virtually or in person, with discussion, activities, exercises, and content. | Emphasizes facilitators be of refugee and immigrant background. Emphasizes value of community as a conduit for healing and sharing of cultural knowledge. |

| World Health Organization (WHO) [25] | Populations affected by adversity | Group Problem Management Plus PM+ Curriculum (stress and problem management, strengthening social support, and resilience). | Psychological intervention for individuals affected by adversity with emotional (depression, anxiety, stress, hopelessness, etc.) and practical problems (employment, housing, etc.). Group exercises, rituals, activities, and case examples. | Adapted for numerous cultures, languages and contexts; Highlights importance of being sensitive to and modifying content for different cultural norms, values, and religions. |

| Hong Fook Mental Health Association (Ho et al., 2002) [20] | Immigrant women from Cambodia, Korean, Chinese (Hong Kong, Mainland China, Taiwan), and Vietnamese communities | Women’s Holistic Health Peer Leadership Training Manual | Training manual to promote individual and collective empowerment for East and Southeast Asian immigrant peer Curriculum focused on 3 core components: understanding holistic health and mental health, exploring mental health perceptions and building communication and outreach skills. | Uses cultural symbols, food and artifacts, Sharing of personal histories and immigration experiences, collective book of stories. Program aided women to have increased understanding and awareness of mental health and illness and available culturally relevant resources; reduced stigma. |

Appendix D

| Intervention | Studies (n) | Populations | Common Cultural Adaptations | Key Outcomes Reported |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mental Health First Aid (MHFA) | 2 | Bhutanese refugees (United States) Iraqi refugees (Australia) |

| Increased mental health knowledge and literacy Improved confidence in helping others experiencing mental health crises Reduced stigma toward mental health services Enhanced help-seeking intentions High program acceptability and feasibility |

| Problem Management Plus (PM+) | 3 | Syrian refugees (Turkey—2 studies) General populations affected by adversity (WHO grey literature) |

| Reduced psychological distressDecreased anxiety& depression symptomsImproved problem-solving and coping skillsBehavioral activation and daily functioning improvementsStrengthened social supportGood feasibility, acceptability, and cultural appropriateness across contexts |

| Self-Help Plus (SH+) | 2 | South Sudanese refugees (Uganda) General populations affected by adversity (WHO grey literature) |

| Stress management improvementProblem-solving skill developmentBehavioral activation Social support strengtheningSuitable for diverse cultural contexts Self-guided format Increases accessibility |

| ALMA (Amigas Latinas Motivando el Alma / Latina Friends Motivating the Soul) | 2 | Spanish-speaking immigrant Latina women (United States—2 studies) |

| Enhanced mindfulness and self-compassionImproved stress management and copingStrengthened social support networksIncreased cultural connection and sense of belonging High engagement and participant satisfactionCommunity empowerment |

References

- Kalich, A.; Heinemann, L.; Ghahari, S. A Scoping Review of Immigrant Experience of Health Care Access Barriers in Canada. J. Immigr. Minor. Health 2016, 18, 697–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomson, M.S.; Chaze, F.; George, U.; Guruge, S. Improving Immigrant Populations’ Access to Mental Health Services in Canada: A Review of Barriers and Recommendations. J. Immigr. Minor. Health 2015, 17, 1895–1905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Mental Health of Refugees and Migrants: Risk and Protective Factors and Access to Care. Available online: https://iris.who.int/server/api/core/bitstreams/34945744-055a-4f3c-b931-d81a2bcf8f34/content (accessed on 30 October 2025).

- Scoglio, A.A.; Salhi, C. Violence Exposure and Mental Health among Resettled Refugees: A Systematic Review. Trauma Violence Abus. 2020, 22, 1192–1206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sigvardsdotter, E.; Vaez, M.; Hedman, A.M.; Saboonchi, F. Prevalence of Torture and Other War-Related Traumatic Events in Forced Migrants: A Systematic Review. J. Rehabil. Torture Vict. Prev. Torture 2016, 26, 41–73. [Google Scholar]

- Bustamante, L.H.U.; Cerqueira, R.O.; Leclerc, E.; Brietzke, E. Stress, Trauma, and Posttraumatic Stress Disorder in Migrants: A Comprehensive Review. Braz. J. Psychiatry 2018, 40, 220–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Franks, W.; Gawn, N.; Bowden, G. Barriers to Access to Mental Health Services for Migrant Workers, Refugees and Asylum Seekers. J. Public Ment. Health 2007, 6, 33–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Na, S.; Ryder, A.G.; Kirmayer, L.J. Toward a Culturally Responsive Model of Mental Health Literacy: Facilitating Help-Seeking among East Asian Immigrants to North America. Am. J. Community Psychol. 2016, 58, 211–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fox, S.; Kramer, E.; Agrawal, P.; Aniyizhai, A. Refugee and Migrant Health Literacy Interventions in High-Income Countries: A Systematic Review. J. Immigr. Minor. Health 2022, 24, 207–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dingwall, K.M.; Puszka, S.; Sweet, M.; Nagel, T. “Like Drawing into Sand”: Acceptability, Feasibility, and Appropriateness of a New e-Mental Health Resource for Service Providers Working with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander People. Aust. Psychol. 2015, 50, 60–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirmayer, L.J.; Groleau, D.; Guzder, J.; Blake, C.; Jarvis, E. Cultural Consultation: A Model of Mental Health Service for Multicultural Societies. Can. J. Psychiatry 2003, 48, 145–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clelland, N.; Gould, T.; Parker, E. Searching for Evidence: What Works in Indigenous Mental Health Promotion? Health Promot. J. Aust. 2007, 18, 208–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peters, M.D.; Marnie, C.; Tricco, A.C.; Pollock, D.; Munn, Z.; Alexander, L.; McInerney, P.; Godfrey, C.M.; Khalil, H. Updated Methodological Guidance for the Conduct of Scoping Reviews. JBI Evid. Synth. 2020, 18, 2119–2126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peters, M.D.; Marnie, C.; Colquhoun, H.; Garritty, C.M.; Hempel, S.; Horsley, T.; Langlois, E.V.; Lillie, E.; O’Brien, K.K.; Tunçalp, Ö.; et al. Scoping Reviews: Reinforcing and Advancing the Methodology and Application. Syst. Rev. 2021, 10, 263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O’Brien, K.K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Moher, D.; Peters, M.D.J.; Horsley, T.; Weeks, L.; et al. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation. Ann. Intern. Med. 2018, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernal, G.; Jiménez-Chafey, M.I.; Domenech Rodríguez, M.M. Cultural Adaptation of Treatments: A Resource for Considering Culture in Evidence-Based Practice. Prof. Psychol. Res. Pract. 2009, 40, 361–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akhtar, A.; Engels, M.H.; Bawaneh, A.; Bird, M.; Bryant, R.; Cuijpers, P.; Hansen, P.; Al-Hayek, H.; Ilkkursun, Z.; Kurt, G.; et al. Cultural Adaptation of a Low-Intensity Group Psychological Intervention for Syrian Refugees. Intervention 2021, 19, 48–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chow, W.; Law, S.; Andermann, L.; Yang, J.; Leszcz, M.; Wong, J.; Sadavoy, J. Multi-Family Psycho-Education Group for Assertive Community Treatment Clients and Families of Culturally Diverse Background: A Pilot Study. Community Ment. Health J. 2010, 46, 364–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekblad, S. To Increase Mental Health Literacy and Human Rights among New-Coming, Low-Educated Mothers with Experience of War: A Culturally, Tailor-Made Group Health Promotion Intervention with Participatory Methodology Addressing Indirectly the Children. Front. Psychiatry 2020, 11, 611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, M.; Tse, Y.H.; Wong, J.P.-H.; Wong, Y.-L.R. Women’s Holistic Health Peer Leadership Training Manual (For Health Educators & Trainers/Social Workers/Community Workers). Hong Fook Mental Health Association. Funded by the Ontario Women’s Health Council, March 2002. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/318402811_Womens_Holistic_Health_Peer_Training_Manual_March_2002 (accessed on 30 October 2025).

- Martinez, A.B.; Lau, J.Y.; Morillo, H.M.; Brown, J.S. ‘C’mon, Let’s Talk: A Pilot Study of Mental Health Literacy Program for Filipino Migrant Domestic Workers in the United Kingdom. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2024, 59, 385–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nogueira, A.L.; Schmidt, I. “One Cannot Make It Alone”: Experiences of a Community Faith-Based Initiative to Support Latino Mental Health. Soc. Work Ment. Health 2022, 20, 645–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koch, T.; Ehring, T.; Liedl, A. Effectiveness of a Transdiagnostic Group Intervention to Enhance Emotion Regulation in Young Afghan Refugees: A Pilot Randomized Controlled Study. Behav. Res. Ther. 2020, 132, 103689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morales, F.R.; Rojas Perez, O.F.; Silva, M.A.; Paris, M., Jr.; Garcini, L.M.; Domenech Rodríguez, M.M.; Mercado, A. Teaching DBT Skills to DACA Recipients and Their Families: Findings from an ECHO Program. Pract. Innov. 2022, 7, 327–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Problem Management Plus (PM+): Individual Psychological Help for Adults Impaired by Distress in Communities Exposed to Adversity (Generic Field-Trial Version 1.1); World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018; Available online: https://iris.who.int/server/api/core/bitstreams/0d493975-285d-4d0b-86b1-2365cfe45748/content (accessed on 30 October 2025).

- Sabri, B.; Vroegindewey, A.; Hagos, M. Development, Feasibility, Acceptability and Preliminary Evaluation of the Internet and Mobile Phone-Based BSHAPE Intervention for Immigrant Survivors of Cumulative Trauma. Contemp. Clin. Trials 2021, 110, 106591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kiropoulos, L.A.; Griffiths, K.M.; Blashki, G. Effects of a Multilingual Information Website Intervention on the Levels of Depression Literacy and Depression-Related Stigma in Greek-Born and Italian-Born Immigrants Living in Australia: A Randomized Controlled Trial. J. Med. Internet Res. 2011, 13, E34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Self-Help Plus (SH+): A Group-Based Stress Management Course for Adults; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021; Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240035119 (accessed on 30 October 2025).

- World Health Organization. The Self-Help Plus (SH+) Training Manual: For Training Facilitators to Deliver the SH+ Course; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2024; Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240095052 (accessed on 30 October 2025).

- Omidian, P.A. Developing Culturally Relevant Psychosocial Training for Afghan Teachers. Intervention 2012, 10, 237–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slewa-Younan, S.; Guajardo, M.G.U.; Mohammad, Y.; Lim, H.; Martinez, G.; Saleh, R.; Sapucci, M. An Evaluation of a Mental Health Literacy Course for Arabic Speaking Religious and Community Leaders in Australia: Effects on Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Related Knowledge, Attitudes and Help-Seeking. Int. J. Ment. Health Syst. 2020, 14, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poudel-Tandukar, K.; Jacelon, C.S.; Poudel, K.C.; Bertone-Johnson, E.R.; Rai, S.; Ramdam, P.; Hollon, S.D. Mental Health Promotion among Resettled Bhutanese Adults in Massachusetts: Results of a Peer-Led Family-Centred Social and Emotional Well-Being (SEW) Intervention Study. Health Soc. Care Community 2022, 30, 1869–1880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slewa-Younan, S.; McKenzie, M.; Thomson, R.; Smith, M.; Mohammad, Y.; Mond, J. Improving the Mental Wellbeing of Arabic Speaking Refugees: An Evaluation of a Mental Health Promotion Program. BMC Psychiatry 2020, 20, 382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tol, W.A.; Augustinavicius, J.; Carswell, K.; Brown, F.L.; Adaku, A.; Leku, M.R.; García-Moreno, C.; Ventevogel, P.; White, R.G.; Van Ommeren, M. Translation, Adaptation, and Pilot of a Guided Self-Help Intervention to Reduce Psychological Distress in South Sudanese Refugees in Uganda. Glob. Ment. Health 2018, 5, E25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Im, H.; Swan, L.E. “We Learn and Teach Each Other”: Interactive Training for Cross-Cultural Trauma-Informed Care in the Refugee Community. Community Ment. Health J. 2022, 58, 917–929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Im, H.; Jettner, J.F.; Warsame, A.H.; Isse, M.M.; Khoury, D.; Ross, A.I. Trauma-Informed Psychoeducation for Somali Refugee Youth in Urban Kenya: Effects on PTSD and Psychosocial Outcomes. J. Child Adolesc. Trauma 2018, 11, 431–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poudel-Tandukar, K.; Jacelon, C.S.; Rai, S.; Ramdam, P.; Bertone-Johnson, E.R.; Hollon, S.D. Social and Emotional Wellbeing (SEW) Intervention for Mental Health Promotion among Resettled Bhutanese Adults in Massachusetts. Community Ment. Health J. 2021, 57, 1318–1327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- HIAS. HIAS Mental Health and Psychosocial Support (MHPSS) Curriculum: Support Group Facilitator Guide; HIAS: Vienna, VA, USA, 2021; Available online: https://www.hias.org (accessed on 30 October 2025).

- Bentley, J.A.; Feeny, N.C.; Dolezal, M.L.; Klein, A.; Marks, L.H.; Graham, B.; Zoellner, L.A. Islamic Trauma Healing: Integrating Faith and Empirically Supported Principles in a Community-Based Program. Cogn. Behav. Pract. 2021, 28, 167–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tran, A.N.; Ornelas, I.J.; Perez, G.; Green, M.A.; Lyn, M.J.; Corbie-Smith, G. Evaluation of Amigas Latinas Motivando El Alma (ALMA): A Pilot Promotora Intervention Focused on Stress and Coping among Immigrant Latinas. J. Immigr. Minor. Health 2014, 16, 280–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramsden, I.M. Cultural Safety and Nursing Education in Aotearoa and Te Waipounamu. Ph.D. Thesis, Victoria University of Wellington, Wellington, New Zealand, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Papps, E.; Ramsden, I. Cultural Safety in Nursing: The New Zealand Experience. Int. J. Qual. Health Care 1996, 8, 491–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Curtis, E.; Jones, R.; Tipene-Leach, D.; Walker, C.; Loring, B.; Paine, S.J.; Reid, P. Why Cultural Safety Rather than Cultural Competency Is Required to Achieve Health Equity: A Literature Review and Recommended Definition. Int. J. Equity Health 2019, 18, 174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirmayer, L.J. Rethinking Cultural Competence. Transcult. Psychiatry 2012, 49, 149–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirmayer, L.J.; Jarvis, G.E. Culturally Responsive Services as a Path to Equity in Mental Healthcare. Healthcare Papers 2019, 18, 11–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jorm, A.F. Mental Health Literacy: Empowering the Community to Take Action for Better Mental Health. Am. Psychol. 2012, 67, 231–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kutcher, S.; Wei, Y.; Coniglio, C. Mental Health Literacy: Past, Present, and Future. Can. J. Psychiatry 2016, 61, 154–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Resnicow, K.; Baranowski, T.; Ahluwalia, J.S.; Braithwaite, R.L. Cultural Sensitivity in Public Health: Defined and Demystified. Ethn. Dis. 1999, 9, 10–21. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Barrera, M., Jr.; Castro, F.G. A Heuristic Framework for the Cultural Adaptation of Interventions. Clin. Psychol. Sci. Pract. 2006, 13, 311–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gone, J.P.; Trimble, J.E. American Indian and Alaska Native Mental Health: Diverse Perspectives on Enduring Disparities. Annu. Rev. Clin. Psychol. 2012, 8, 131–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kirmayer, L.J.; Whitley, R.; Fauras, V. Community Team Approaches to Mental Health Services and Wellness Promotion; Culture and Mental Health Research Unit Working Paper No. 15; Culture and Mental Health Research Unit, Jewish General Hospital: Montreal, QC, Canada, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Benish, S.G.; Quintana, S.; Wampold, B.E. Culturally Adapted Psychotherapy and the Legitimacy of Myth: A Direct-Comparison Meta-Analysis. J. Couns. Psychol. 2011, 58, 279–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Repper, J.; Carter, T. A Review of the Literature on Peer Support in Mental Health Services. J. Ment. Health 2011, 20, 392–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durie, M. A Maori Perspective of Health. Soc. Sci. Med. 1985, 20, 483–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gone, J.P. Redressing First Nations Historical Trauma: Theorizing Mechanisms for Indigenous Culture as Mental Health Treatment. Transcult. Psychiatry 2013, 50, 683–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhugra, D.; Becker, M.A. Migration, Cultural Bereavement and Cultural Identity. World Psychiatry 2005, 4, 18–24. [Google Scholar]

- Porter, M.; Haslam, N. Predisplacement and Postdisplacement Factors Associated with Mental Health of Refugees and Internally Displaced Persons: A Meta-Analysis. JAMA 2005, 294, 602–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirkbride, J.B.; Anglin, D.M.; Colman, I.; Dykxhoorn, J.; Jones, P.B.; Patalay, P.; Pitman, A.; Soneson, E.; Steare, T.; Wright, T.; et al. The Social Determinants of Mental Health and Disorder: Evidence, Prevention and Recommendations. World Psychiatry 2024, 23, 58–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Mental Health and Psychosocial Considerations During the COVID-19 Outbreak. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO-2019-nCoV-MentalHealth-2020.1 (accessed on 30 October 2025).

- Murray, L.K.; Dorsey, S.; Haroz, E.; Lee, C.; Alsiary, M.M.; Haydary, A.; Weiss, W.M.; Bolton, P. A Common Elements Treatment Approach for Adult Mental Health Problems in Low- and Middle-Income Countries. Cogn. Behav. Pract. 2014, 21, 111–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sijbrandij, M.; Kunovski, I.; Cuijpers, P. Effectiveness of Internet-Delivered Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Posttraumatic Stress Disorder: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Depress. Anxiety 2016, 34, 783–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bronfenbrenner, U. The Ecology of Human Development: Experiments by Nature and Design; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1979; Volume 352. [Google Scholar]

- Ungar, M. The Social Ecology of Resilience: Addressing Contextual and Cultural Ambiguity of a Nascent Construct. Am. J. Orthopsychiatry 2011, 81, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wendt, D.C.; Gone, J.P. Integrating Professional and Indigenous Therapies: An Urban American Indian Narrative Clinical Case Study. Couns. Psychol. 2018, 46, 118–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suite, D.H.; La Bril, R.; Primm, A.; Harrison-Ross, P. Beyond Misdiagnosis, Misunderstanding and Mistrust: Relevance of the Historical Perspective in the Medical and Mental Health Treatment of People of Color. J. Natl. Med. Assoc. 2007, 99, 879–885. [Google Scholar]

- Israel, B.A.; Schulz, A.J.; Parker, E.A.; Becker, A.B. Review of Community-Based Research: Assessing Partnership Approaches to Improve Public Health. Annu. Rev. Public Health 1998, 19, 173–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallerstein, N.B.; Duran, B. Using Community-Based Participatory Research to Address Health Disparities. Health Promot. Pract. 2006, 7, 312–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro, F.G.; Barrera, M., Jr.; Holleran Steiker, L.K. Issues and Challenges in the Design of Culturally Adapted Evidence-Based Interventions. Annu. Rev. Clin. Psychol. 2010, 6, 213–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acarturk, C.; Kurt, G.; İlkkurşun, Z.; de Graaff, A.M.; Bryant, R.; Cuijpers, P.; Fuhr, D.; McDaid, D.; Park, A.L.; Sijbrandij, M.; et al. Effectiveness of Group Problem Management Plus in Distressed Syrian Refugees in Türkiye: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Epidemiol. Psychiatr. Sci. 2024, 33, e43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burchert, S.; Alkneme, M.S.; Alsaod, A.; Cuijpers, P.; Heim, E.; Hessling, J.; Hosny, N.; Sijbrandij, M.; Van’t Hof, E.; Ventevogel, P.; et al. Effects of a Self-Guided Digital Mental Health Self-Help Intervention for Syrian Refugees in Egypt: A Pragmatic Randomized Controlled Trial. PLoS Med. 2024, 21, e1004460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Graaff, A.M.; Cuijpers, P.; Twisk, J.W.R.; Kieft, B.; Hunaidy, S.; Elsawy, M.; Gorgis, N.; Bouman, T.K.; Lommen, M.J.J.; Acarturk, C.; et al. Peer-Provided Psychological Intervention for Syrian Refugees: Results of a Randomised Controlled Trial on the Effectiveness of Problem Management Plus. BMJ Ment. Health 2023, 26, e300637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spaaij, J.; Fuhr, D.C.; Akhtar, A.; Casanova, L.; Klein, T.; Schick, M.; Weilenmann, S.; Roberts, B.; Morina, N. Scaling-Up Problem Management Plus for Refugees in Switzerland: A Qualitative Study. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2023, 23, 488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Purgato, M.; Carswell, K.; Tedeschi, F.; Acarturk, C.; Anttila, M.; Au, T.; Bajbouj, M.; Baumgartner, J.; Biondi, M.; Churchill, R.; et al. Effectiveness of Self-Help Plus in Preventing Mental Disorders in Refugees and Asylum Seekers in Western Europe: A Multinational Randomised Controlled Trial. Psychother. Psychosom. 2021, 90, 403–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acarturk, C.; Uygun, E.; Ilkkursun, Z.; Carswell, K.; Tedeschi, F.; Batu, M.; Eskici, S.; Kurt, G.; Anttila, M.; Au, T.; et al. Effectiveness of a WHO Self-Help Psychological Intervention for Preventing Mental Disorders Among Syrian Refugees in Turkey: A Randomised Controlled Trial. World Psychiatry 2022, 21, 88–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tay, A.K.; Miah, M.A.A.; Khan, S.; Mohsin, M.; Alam, A.N.M.M.; Ozen, S.; Mahmuda, M.; Ahmed, H.U.; Silove, D.; Ventevogel, P. A Naturalistic Evaluation of Group Integrative ADAPT Therapy (IAT-G) with Rohingya Refugees During the Emergency Phase of a Mass Humanitarian Crisis in Cox’s Bazar, Bangladesh. eClinicalMedicine 2021, 38, 100999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arksey, H.; O’Malley, L. Scoping Studies: Towards a Methodological Framework. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 2005, 8, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Lith, T.; Schofield, M.J.; Fenner, P. Identifying the Evidence Base for Art-Based Practices and Their Potential Benefit for Mental Health Recovery: A Critical Review. Disabil. Rehabil. 2013, 35, 1309–1323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stickley, T.; Duncan, K. Art in Mind: Implementation of a Community Arts Initiative to Promote Mental Health. J. Public Ment. Health 2007, 6, 24–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mateos-Fernández, R.; Saavedra, J. Designing and Assessing of an Art-Based Intervention for Undocumented Migrants. Arts Health 2022, 14, 119–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarez, C.; Sanchez-Roman, M.J.; Vrany, E.A.; Mata López, L.R.; Smith, O.; Escobar-Acosta, L.; Hill-Briggs, F. Cuidándome: A Trauma-Informed and Cultural Adaptation of a Chronic Disease Self-Management Program for Latina Immigrant Survivors with a History of Adverse Childhood Experiences and Depression or Anxiety Symptoms. Cult. Divers. Ethn. Minor. Psychol. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garabiles, M.R.; Shehadeh, M.H.; Hall, B.J. Cultural Adaptation of a Scalable World Health Organization e-Mental Health Program for Overseas Filipino Workers. JMIR Form. Res. 2019, 3, E11600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uribe Guajardo, M.G.; Slewa-Younan, S.; Kitchener, B.A.; Mannan, H.; Mohammad, Y.; Jorm, A.F. Improving the Capacity of Community-Based Workers in Australia to Provide Initial Assistance to Iraqi Refugees with Mental Health Problems: An Uncontrolled Evaluation of a Mental Health Literacy Course. Int. J. Ment. Health Syst. 2018, 12, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gurung, A.; Subedi, P.; Zhang, M.; Li, C.; Kelly, T.; Kim, C.; Yun, K. Culturally-Appropriate Orientation Increases the Effectiveness of Mental Health First Aid Training for Bhutanese Refugees: Results from a Multi-State Program Evaluation. J. Immigr. Minor. Health 2020, 22, 957–964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hendriks, T.; Hassankhan, A.; de Jong, J.T.; van Woerkom, M. Improving Resilience and Mental Well-Being among Refugees Residing at Asylum Centers in the Netherlands: A Pre-Post Feasibility Study. Ment. Health Prev. 2024, 36, 200366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernandez, M.Y.; Organista, K.C. Entertainment–Education? A Fotonovela? A New Strategy to Improve Depression Literacy and Help-Seeking Behaviors in at-Risk Immigrant Latinas. Am. J. Community Psychol. 2013, 52, 224–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ornelas, I.J.; Perez, G.; Maurer, S.; Gonzalez, S.; Childs, V.; Price, C.; Scott, M.J.; Amesty, S.; Rao, D. Amigas Latinas Motivando El Alma: In-Person and Online Delivery of an Intervention to Promote Mental Health among Latina Immigrant Women. J. Integr. Complement. Med. 2022, 28, 821–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uygun, E.; Ilkkursun, Z.; Sijbrandij, M.; Aker, A.T.; Bryant, R.; Cuijpers, P.; Kiselev, N.; Morina, N.; Nissen, A.; Ventevogel, P.; et al. Protocol for a Randomized Controlled Trial: Peer-to-Peer Group Problem Management Plus (PM+) for Adult Syrian Refugees in Turkey. Trials 2020, 21, 283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weise, C.; Grupp, F.; Reese, J.P.; Schade-Brittinger, C.; Ehring, T.; Morina, N.; Knaevelsrud, C.; Kamp-Becker, I.; Stoll, M.; Jelinek, L.; et al. Efficacy of a Low-Threshold, Culturally Sensitive Group Psychoeducation Programme for Asylum Seekers (LoPe): Study Protocol for a Multicentre Randomised Controlled Trial. BMJ Open 2021, 11, E047385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xin, H.; Bailey, R.; Jiang, W.; Aronson, R.; Strack, R. A Pilot Intervention for Promoting Multiethnic Adult Refugee Groups’ Mental Health: A Descriptive Article. J. Immigr. Refug. Stud. 2011, 9, 291–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Key Characteristics | Statistics | Details |

|---|---|---|

| Number of Studies | 28 | - |

| Age Range of Participants * | 15–88 | - |

| Country/Study Location | 11 | United States, United Kingdom, Turkey, Germany, Canada, Sweden, Netherlands, Kenya, Australia, Pakistan, Uganda |

| Program Content | - | 2–14 training sessions, facilitated curriculum modules, group discussions, self-paced modules, and fotonovela |

| Cultural Adaptations | - | Linguistic adaptations, cultural symbolism and images, language adaptations, cultural values, cultural and religious stories, religious and spiritual activities, traditional/indigenous healing rituals and practices, arts-based activities, metaphors and proverbs, music, food, oral narratives and storytelling |

| Themes | Key Components |

|---|---|

| Cultural Adaptation and Sensitivity | Surface-level adaptations (language, imagery); deep-level adaptations (values, worldviews, traditional practices); community involvement; culturally informed content |

| Addressing Unique Migration-Related Stressors and Challenges | Psychoeducation on PTSD, depression, anxiety; pre- and post-migration trauma; acculturation stress; discrimination and isolation; context-specific coping skills; system navigation support |

| Integration of Traditional and Western Approaches | Religious and spiritual practices; traditional healing ceremonies; cultural storytelling; indigenous explanatory models; traditional healers as co-facilitators; combined evidence-based and traditional techniques |

| Theoretical Frameworks and Evidence-Based Practices | CBT principles; CBPR approaches; cultural adaptation frameworks; trauma-informed care; social cognitive theory; intersectionality frameworks; evidence-based psychoeducation |

| Evaluation Methodologies | Pre-post designs; follow-up assessments; RCTs with control groups; mixed methods; culturally sensitive measures; assessment of literacy, stigma, symptoms, help-seeking behaviors |

| Application of Holistic Frameworks | Multiple wellbeing dimensions (physical, psychological, social, spiritual); intersectionality lens; social determinants of health; ecological approaches; family and community interventions |

| Community-Based Peer Support Models | Community partnership and co-design; peer and lay provider facilitation; community members as co-designers; cultural brokers; flexible and accessible delivery; train-the-trainer models; ethnic media partnerships |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Thayyilayil, S.A.; Yohani, S.; Cyuzuzo, L.; Kennedy, M.; Salami, B. Culturally Adapted Mental Health Education Programs for Migrant Populations: A Scoping Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2026, 23, 72. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph23010072

Thayyilayil SA, Yohani S, Cyuzuzo L, Kennedy M, Salami B. Culturally Adapted Mental Health Education Programs for Migrant Populations: A Scoping Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2026; 23(1):72. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph23010072

Chicago/Turabian StyleThayyilayil, Shaima Ahammed, Sophie Yohani, Lisa Cyuzuzo, Megan Kennedy, and Bukola Salami. 2026. "Culturally Adapted Mental Health Education Programs for Migrant Populations: A Scoping Review" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 23, no. 1: 72. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph23010072

APA StyleThayyilayil, S. A., Yohani, S., Cyuzuzo, L., Kennedy, M., & Salami, B. (2026). Culturally Adapted Mental Health Education Programs for Migrant Populations: A Scoping Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 23(1), 72. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph23010072