Dose Assessment in Mining Communities in South Africa Using Ecolego Simulation Software

Abstract

1. Introduction

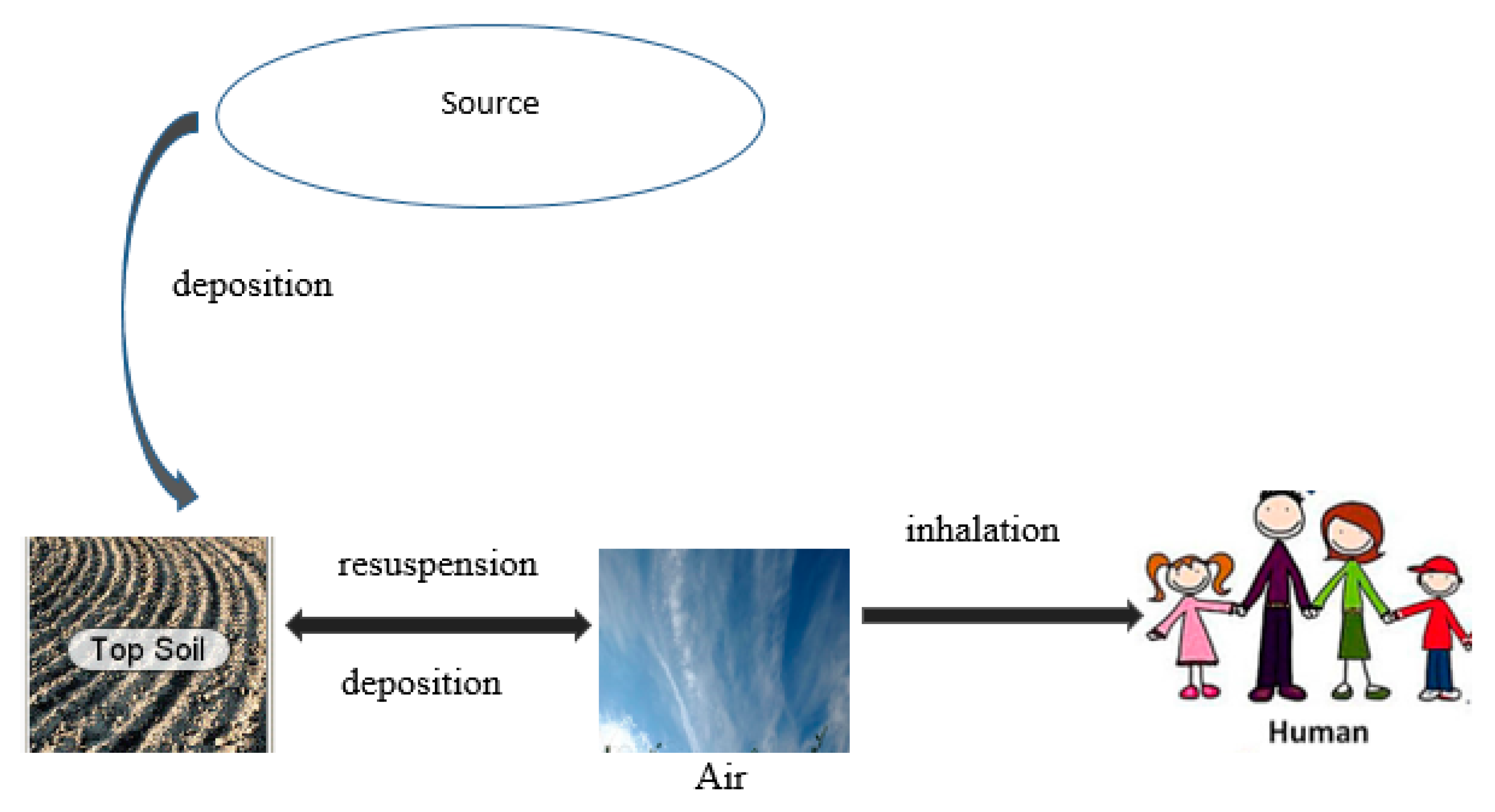

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Description of the Study Areas

2.2. Input Data

2.3. Doses from Inhalation

2.4. Doses from External Exposure

2.5. Calculation of Total Dose

2.6. Concentration in Air

3. Results

3.1. Inhalation Doses

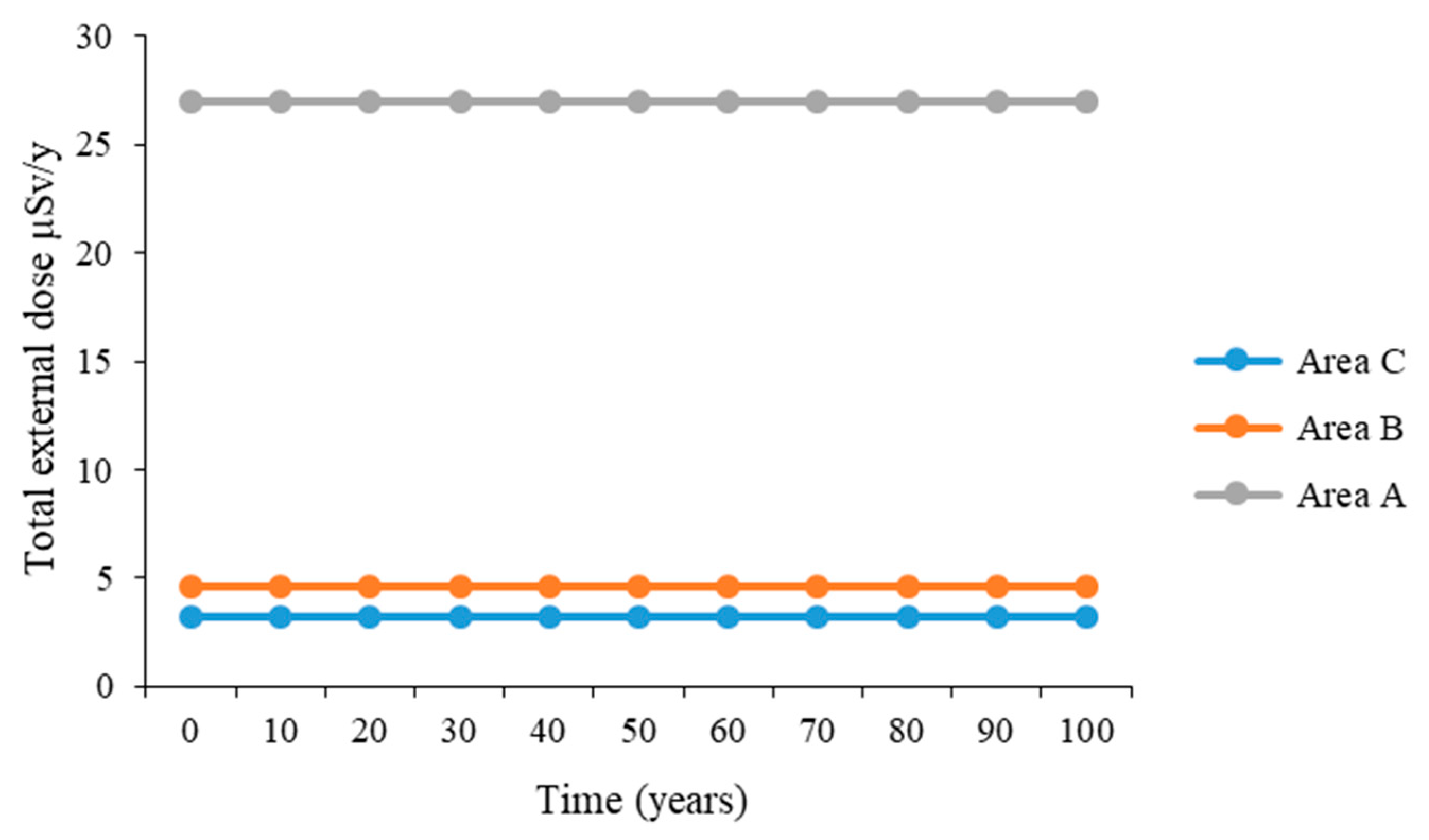

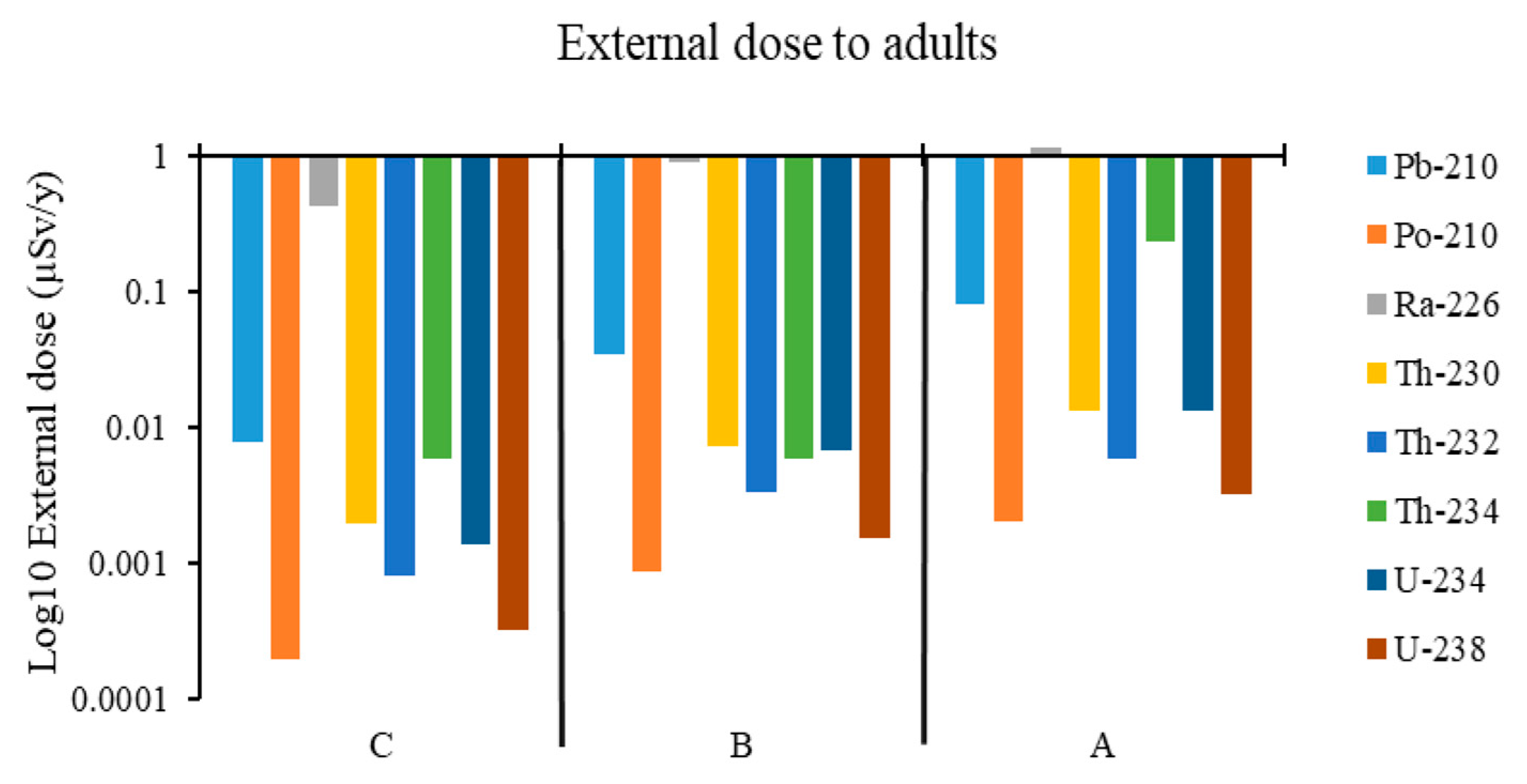

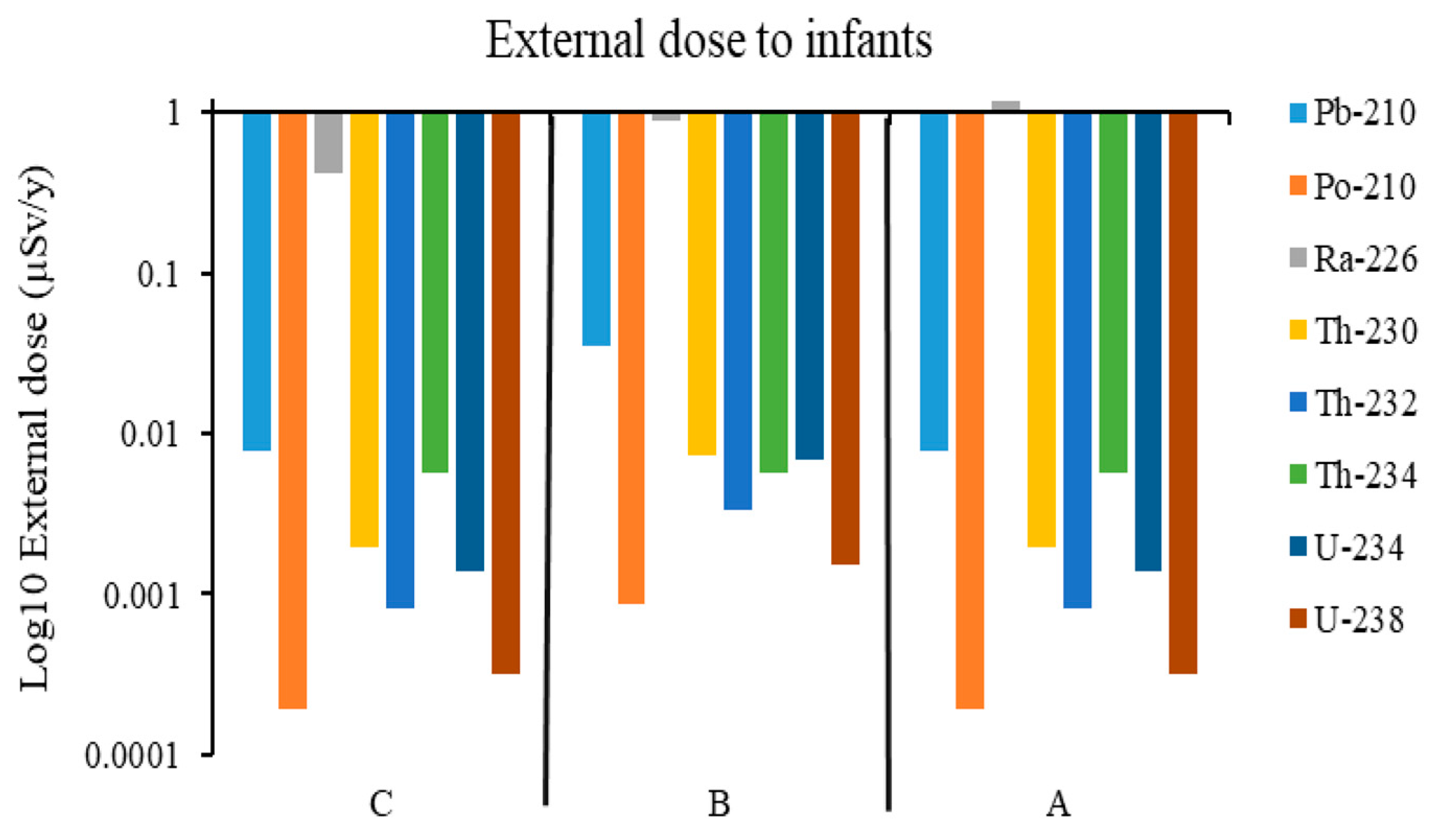

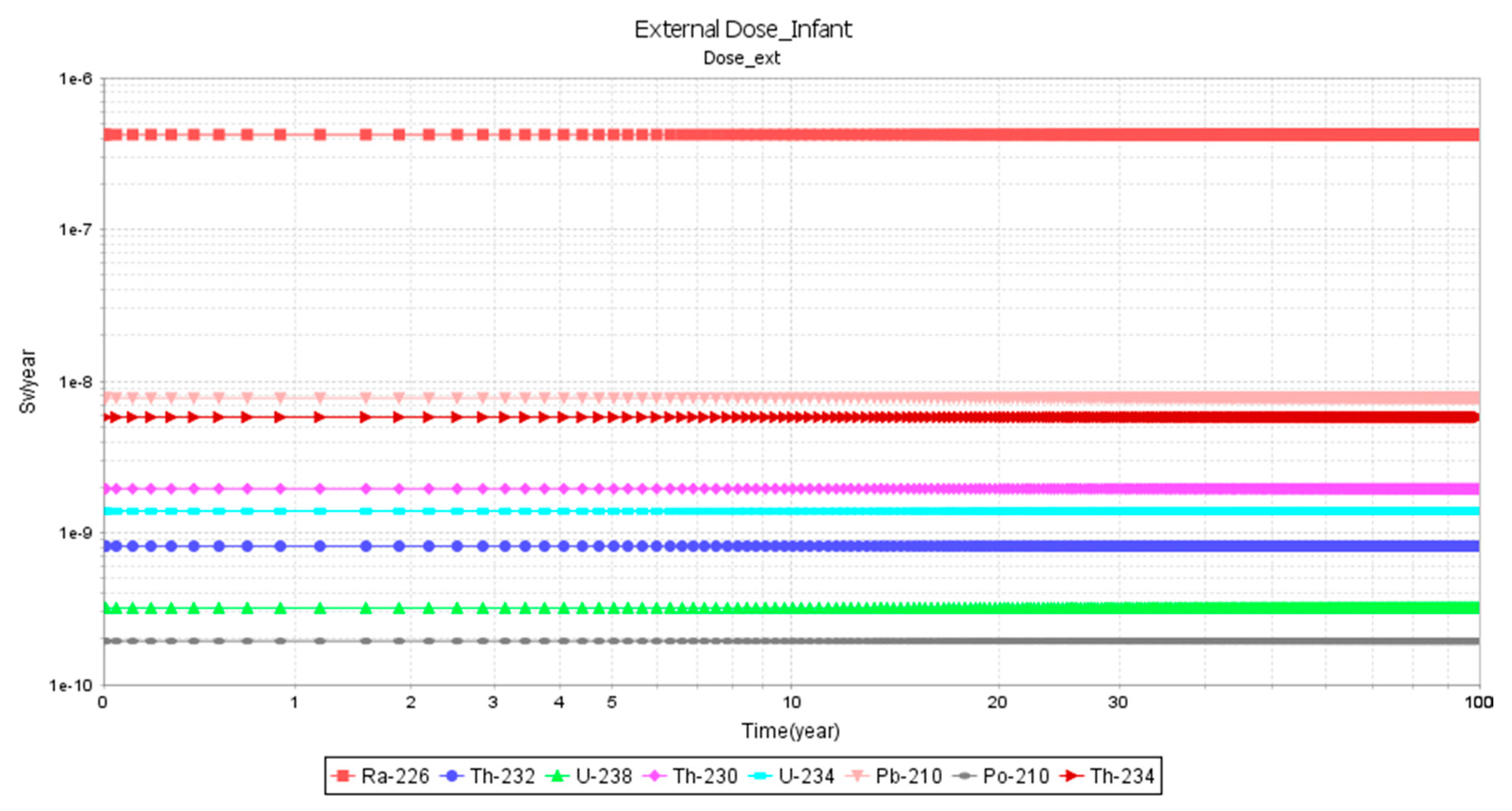

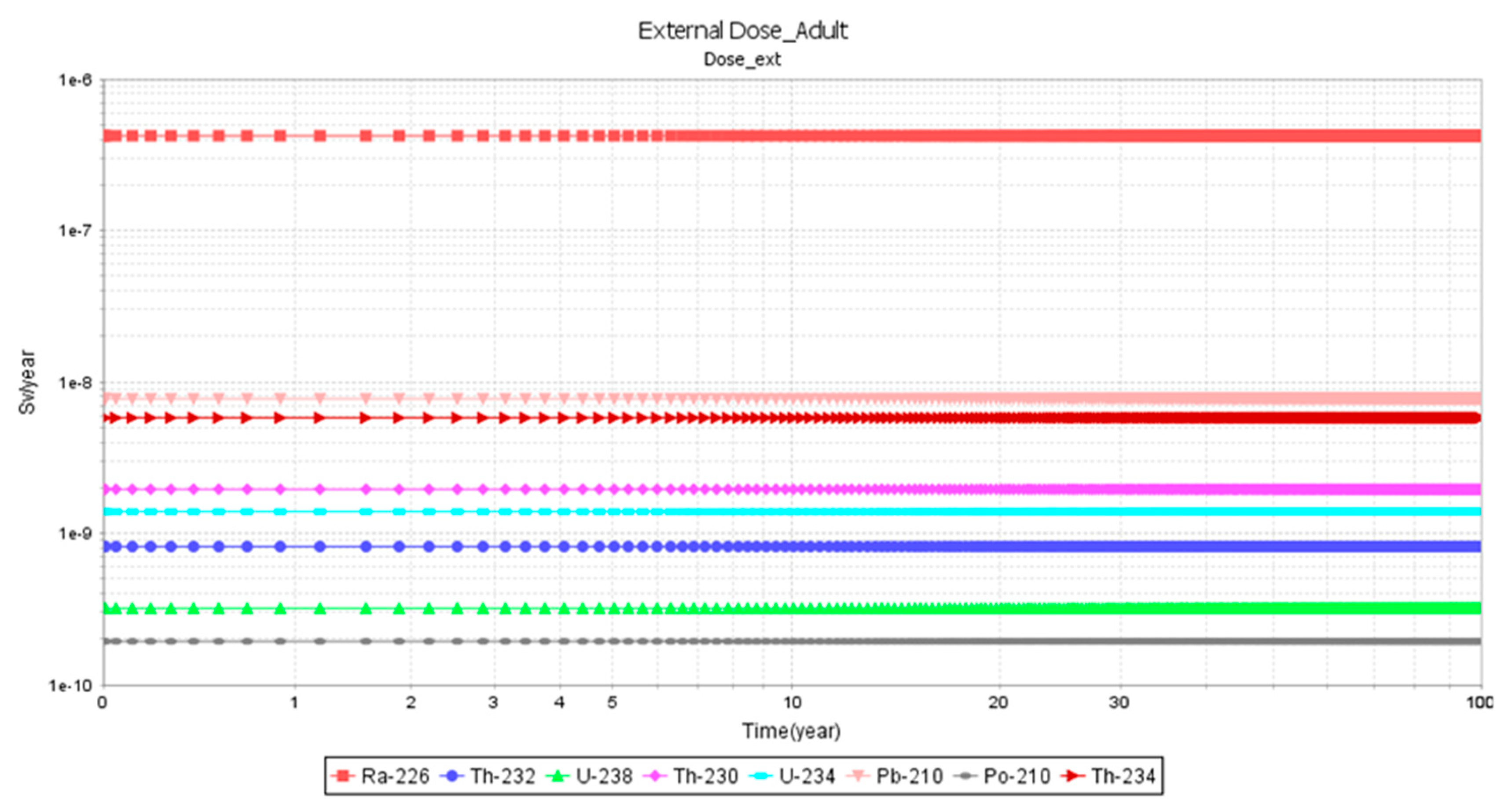

3.2. External Doses

Total External Dose

3.3. Total Dose

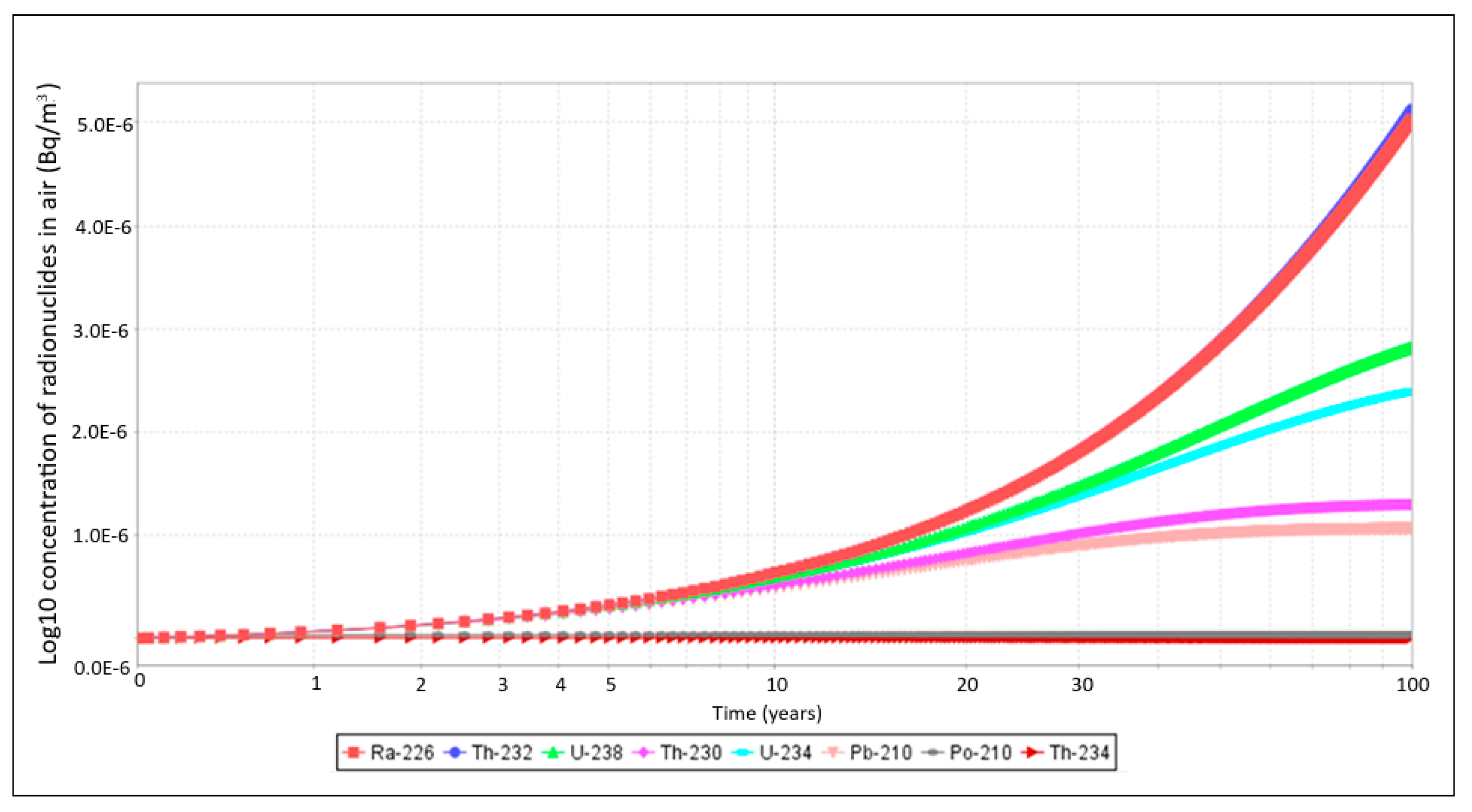

3.4. Concentration of the Radionuclides in Air

4. Discussion

4.1. Trends in Radionuclide Concentrations

4.1.1. Inhalation Doses

4.1.2. External Doses

4.1.3. Total Dose

4.2. Concentration of Radionuclides in Air

Environmental Health Implications for Mining Communities

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ICRP | International Commission on Radiological Protection |

| AMAD | Activity Median Aerodynamic Diameter |

Appendix A. Input Data for ECOLEGO Simulation

| Radionuclide | Half-Life |

|---|---|

| 238U | 4.5 × 109 years |

| 234Th | 24 days |

| 234U | 2.5 × 105 years |

| 230Th | 7.5 × 104 years |

| 226Ra | 1600 years |

| 210Pb | 22.2 years |

| 210Po | 138 days |

| 232Th | 1.405 × 1010 years |

| Nuclide | Adult | Infant |

|---|---|---|

| 238U | 8.0 × 10−6 | 2.5 × 10−5 |

| 232Th | 2.5 × 10−5 | 5.0 × 10−5 |

| 210Pb | 5.6 × 10−6 | 1.8 × 10−5 |

| 226Ra | 9.5 × 10−6 | 2.9 × 10−5 |

| 210Po | 4.3 × 10−6 | 1.4 × 10−5 |

| 230Th | 1.4 × 10−5 | 3.5 × 10−5 |

| 234Th | 7.7 × 10−9 | 3.1 × 10−8 |

| 234U | 9.4 × 10−6 | 2.9 × 10−5 |

| Adult | Infant |

|---|---|

| 1 m3/h | 0.16 m3/h |

| Nuclide | |

|---|---|

| 238U | 1.5 × 10−18 |

| 232Th | 8.8 × 10−18 |

| 226Ra | 5.6 × 10−16 |

| 210Pb | 3.8 × 10−17 |

| 210Po | 9.5 × 10−19 |

| 230Th | 2.1 × 10−17 |

| 234Th | 4.12 × 10−16 |

| 234U | 6.6 × 10−18 |

| Nuclide | (Bq/m3) |

|---|---|

| 238U | 1.0 × 10−6 |

| 232Th | 5.0 × 10−7 |

| 226Ra | 1.0 × 10−6 |

| 210Pb | 9.5 × 10−7 |

| 210Po | 9.5 × 10−7 |

| 230Th | 5.0 × 10−7 |

| 234Th | 1.0 × 100 |

| 234U | 1.0 × 10−6 |

| Nuclide | A | B | C |

|---|---|---|---|

| 238U | 151.76 | 73.39 | 15.20 |

| 232Th | 47.52 | 27.29 | 6.62 |

| 226Ra | 147 | 113.14 | 53.59 |

| 210Pb | 151 | 72 | 15 |

| 210Po | 150 | 70 | 14.5 |

| 230Th | 44.5 | 25 | 6.00 |

| 234Th | 40 | 23 | 6.5 |

| 234U | 140.5 | 65.5 | 12.0 |

| Value | 3.13 × 10−5 |

| norm (mean = 2.1 × 10−5, sd = 3.38 × 10−7, trmin = 6.618 × 10−6, trmax = 5.63 × 10−5) | |

| Min value | 6.616 × 10−6 |

| Max value | 5.63 × 10−5 |

| Nuclide | |

|---|---|

| 238U | 0.02 |

| 232Th | 0.005 |

| 226Ra | 0.005 |

| 210Pb | 0.03 |

| 210Po | 0.04 |

| 230Th | 0.05 |

| 234Th | 0.05 |

| 234U | 0.025 |

References

- Pandey, B.; Agrawal, M.; Singh, S. Assessment of Air Pollution around Coal Mining Area: Emphasizing on Spatial Distributions, Seasonal Variations, and Heavy Metals, Using Cluster and Principal Component Analysis. Atmos. Pollut. Res. 2014, 5, 79–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dlamini, S.; Mathuthu, M.; Tshivhase, V. Radionuclides and Toxic Elements Transfer from the Princess Dump to Water in Roodepoort, South Africa. J. Environ. Radioact. 2016, 153, 201–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nkosi, V.; Wichmann, J.; Voyi, K. Chronic Respiratory Disease among the Elderly in South Africa: Any Association with Proximity to Mine Dumps? Environ. Health 2015, 14, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Černe, M.; Smodiš, B.; Štrok, M. Uptake of Radionuclides by a Common Reed (Phragmites australis (Cav.) Trin. ex Steud.) Grown in the Vicinity of the Former Uranium Mine at Žirovski Vrh. Nucl. Eng. Des. 2011, 241, 1282–1286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ono, F.B.; Guilherme, L.R.G.; Penido, E.S.; Carvalho, G.S.; Hale, B.; Toujaguez, R.; Bundschuh, J. Arsenic Bioaccessibility in a Gold Mining Area: A Health Risk Assessment for Children. Environ. Geochem. Health 2012, 34, 457–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations Scientific Committee on the Effects of Atomic Radiation (UNSCEAR). Developments since the 2013 UNSCEAR Report on the Levels and Effects of Radiation Exposure Due to the Nuclear Accident Following the Great East-Japan Earthquake and Tsunami; A 2015 White Paper to Guide the Scientific Committee’s Future Programme of Work; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fadol, N.; Salih, I.; Idriss, H.; Elfaki, A.; Sam, A. Investigation of Natural Radioactivity Levels in Soil Samples from North Kordofan State, Sudan. Res. J. Phys. Sci. 2015, 2320, 4796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karahan, G. Risk Assessment of Baseline Outdoor Gamma Dose Rate Levels: Study of Natural Radiation Sources in Bursa, Turkey. Radiat. Prot. Dosim. 2010, 142, 324–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Avila, R.; Broed, R.; Pereira, A. ECOLEGO—A Toolbox for Radioecological Risk Assessment. In Proceedings of the International Conference on the Protection from the Effects of Ionizing Radiation, IAEA-CN-109/80, Stockholm, Sweden, 6–10 October 2003; International Atomic Energy Agency: Stockholm, Sweden, 2003; pp. 229–232. Available online: https://inis.iaea.org/records/1tck4-tcd54 (accessed on 14 August 2025).

- O’Brien, R.; Cooper, M. Technologically Enhanced Naturally Occurring Radioactive Material (NORM): Pathway Analysis and Radiological Impact. Appl. Radiat. Isot. 1998, 49, 227–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avila, R.; Bergström, U. Methodology for Calculation of Doses to Man and Implementation in Pandora; SKB: Coimbatore, Tamil Nadu, India, 2006; Available online: https://www.skb.com/publication/1146338/ (accessed on 14 August 2025).

- Corrigall, R. Generic Models for Use in Assessing the Impact of Discharges of Radioactive Substances to the Environment; IAEA Safety Reports Series No. 19; IAEA: Vienna, Austria, 2004; Volume 77, p. 216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monte, L. Modelling Multiple Dispersion of Radionuclides through the Environment. J. Environ. Radioact. 2010, 101, 134–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walther, C.; Gupta, D.K. Radionuclides in the Environment; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathuthu, M.; Khumalo, N. Determination of Lead Isotope Ratios in Uranium Mine Products in South Africa by Means of Inductively Coupled Plasma Mass Spectrometry. J. Radioanal. Nucl. Chem. 2017, 315, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robb, L.J.; Meyer, F.M. The Witwatersrand Basin, South Africa: Geological Framework and Mineralization Processes. Ore Geol. Rev. 1995, 10, 67–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Commission on Radiological Protection (ICRP). Compendium of Dose Coefficients Based on ICRP Publication 60 (ICRP Publication 119, Ann ICRP 41 [Suppl.]). Ann. ICRP 2012, 40, 1–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, C.H.; Park, J.W. Analysis of the Natural Radioactivity Concentrations of the Fine Dust Samples in Jeju Island, Korea, and the Annual Effective Radiation Dose by Inhalation. J. Radioanal. Nucl. Chem. 2018, 316, 1173–1179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kudryashev, V.A.; Kim, D.S. Determination of the Total Effective Dose of External and Internal Exposure by Different Ionizing Radiation Sources. Radiat. Prot. Dosim. 2019, 187, 129–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chevychelov, A.; Sobakin, P.; Gorokhov, A.; Kuznetsova, L.; Alekseev, A. Migration of 238U and 226Ra Radionuclides in Technogenic Permafrost Taiga Landscapes of Southern Yakutia, Russia. Water 2021, 13, 966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dowdall, M.; Selnaes, Ø.G.; Gwynn, J.P.; Davids, C. Simultaneous Determination of 226Ra and 238U in Soil and Environmental Materials by Gamma-Spectrometry in the Absence of Radium Progeny Equilibrium. J. Radioanal. Nucl. Chem. 2004, 261, 513–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pöschl, M.; Nollet, L.M. Radionuclide Concentrations in Food and the Environment; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hjerpe, T.; Broed, R. Radionuclide Transport and Dose Assessment Modelling in Biosphere Assessment 2009; Posiva Oy: Olkiluoto, Finland, 2010; No. POSIVA-WR--10-79; Available online: https://inis.iaea.org/records/wy5pk-7jk61 (accessed on 14 August 2025).

- Appleton, J.D. Radon in Air and Water. In Essentials of Medical Geology; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeboah, S.M. Indoor Radon in Selected Homes in Aburi Municipality: Measurement Uncertainty, Decision Analysis and Remediation Strategy; University of Ghana: Accra, Ghana, 2014; Available online: https://inis.iaea.org/records/jfz7p-16687 (accessed on 14 August 2025).

- Naja, G.M.; Volesky, B. Toxicity and Sources of Pb, Cd, Hg, Cr, As, and Radionuclides in the Environment. Heavy Met. Environ. 2009, 8, 16–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murty, V.; Karunakara, N. Natural Radioactivity in the Soil Samples of Botswana. Radiat. Meas. 2008, 43, 1541–1545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robison, L.L.; Hudson, M.M. Survivors of Childhood and Adolescent Cancer: Life-Long Risks and Responsibilities. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2014, 14, 61–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kutanzi, K.R.; Lumen, A.; Koturbash, I.; Miousse, I.R. Pediatric Exposures to Ionizing Radiation: Carcinogenic Considerations. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2016, 13, 1057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grasty, R.; LaMarre, J. The annual effective dose from natural sources of ionising radiation in Canada. Radiat. Prot. Dosim. 2004, 108, 215–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Csavina, J.; Field, J.; Taylor, M.P.; Gao, S.; Landázuri, A.; Betterton, E.A.; Sáez, A.E. A Review on the Importance of Metals and Metalloids in Atmospheric Dust and Aerosol from Mining Operations. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2012, 433, 58–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kafu-Quvane, B.; Mlaba, S. Assessing the Impact of Quarrying as an Environmental Ethic Crisis: A Case Study of Limestone Mining in a Rural Community. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2024, 21, 458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sutton, M.W.; Weiersbye, I. Land-Use After Mine Closure—Risk Assessment of Gold and Uranium Mine Residue Deposits on the Eastern Witwatersrand, South Africa. In Mine Closure 2008: Proceedings of the Third International Seminar on Mine Closure; Australian Centre for Geomechanics: Crawley, Australia, 2008; pp. 363–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| source | deposition | ||

| surface soil | transfer | ||

| air | transfer | ||

| human |

| Radionuclide | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Area | Pb-210 | Po-210 | Ra-226 | Th-230 | Th-232 | Th-234 | U-234 | U-238 |

| Adult | ||||||||

| Mine A | 0.0466 | 0.0358 | 0.0832 | 0.0613 | 0.1095 | 67.45 | 0.0823 | 0.0701 |

| Mine B | 0.0466 | 0.0358 | 0.0832 | 0.0613 | 0.1095 | 271.56 | 0.0823 | 0.0701 |

| Mine C | 0.0466 | 0.0358 | 0.0832 | 0.0613 | 0.1095 | 271.56 | 0.0823 | 0.0701 |

| Infant | ||||||||

| Mine A | 0.0240 | 0.0186 | 0.0406 | 0.0245 | 0.0350 | 43.45 | 0.0406 | 0.0350 |

| Mine B | 0.0240 | 0.0186 | 0.0406 | 0.0245 | 0.0350 | 43.45 | 0.0406 | 0.0350 |

| Mine C | 0.0240 | 0.0186 | 0.0406 | 0.0245 | 0.0350 | 43.45 | 0.0406 | 0.0350 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Dudu, V.P.; Ilunga, M.; Chabalala, D.T.; Mathuthu, M. Dose Assessment in Mining Communities in South Africa Using Ecolego Simulation Software. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2026, 23, 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph23010003

Dudu VP, Ilunga M, Chabalala DT, Mathuthu M. Dose Assessment in Mining Communities in South Africa Using Ecolego Simulation Software. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2026; 23(1):3. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph23010003

Chicago/Turabian StyleDudu, Violet Patricia, Masengo Ilunga, Dunisani Thomas Chabalala, and Manny Mathuthu. 2026. "Dose Assessment in Mining Communities in South Africa Using Ecolego Simulation Software" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 23, no. 1: 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph23010003

APA StyleDudu, V. P., Ilunga, M., Chabalala, D. T., & Mathuthu, M. (2026). Dose Assessment in Mining Communities in South Africa Using Ecolego Simulation Software. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 23(1), 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph23010003