Patterns of Elder Caregiving Among Nigerians: An Integrative Review

Highlights

- Synthesizes evidence on elder caregiving within Nigeria’s rapidly aging population, highlighting how family-based care functions as a primary public health response in the absence of robust formal systems.

- Examines how cultural norms, migration, gender roles, and socioeconomic constraints shape care arrangements, access to services, and health outcomes for older adults in a low-resource context.

- Provides the first integrative, intersectional synthesis of elder caregiving in Nigeria, clarifying how cultural, familial, economic, psychosocial, and policy factors jointly determine health vulnerabilities and care inequities.

- Demonstrates how intersecting gendered, class-based, and regional disparities in caregiving contribute to unmet health and social needs, caregiver strain, and uneven access to geriatric and supportive services across the country.

- Calls for evidence-informed interventions, including caregiver support programs, gender-sensitive policies, strengthened geriatric services, and community-based care models to address gaps in access, equity, and caregiver well-being.

- Identifies critical research and policy priorities, including intersectional and multilingual approaches, improved monitoring of caregiving outcomes, and expanded study of transnational elder care among Nigerian diaspora communities.

Abstract

1. Introduction

Problem Formulation

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Theoretical Perspectives

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

2.3. Literature Search Stage

2.4. Data Extraction and Quality Appraisal

2.5. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Study Characteristics

3.2. Themes and Sub-Themes

3.3. Cultural Influences

3.4. Gender Differences

3.5. Family Dynamics

3.6. Economic Factors

3.7. Caregiver Strain and Psychosocial Dimensions

3.8. Government Policies and Support

4. Discussion

4.1. Implications for Policymakers, Practitioners, and Researchers

4.2. Key Recommendations

- Develop comprehensive support systems: Government agencies should prioritize the development of comprehensive support systems that address the challenges faced by caregivers, including conflicting responsibilities, limited healthcare access, and a lack of formal support. A National Caregiver Support Package can include care navigation embedded in primary health centers to link caregivers to available benefits and services. Respite programs can be made accessible through registered community providers, while transport and medication subsidies can be allocated based on standardized ADL and IADL assessments. A 24 h caregiver helpline and a digital caregiver registry enable rapid referrals and visibility across service networks.

- Strengthen community-based initiatives: Community organizations and local interest holders may expand caregiver support through rotating respite services, peer groups, and targeted training. In rural areas, where caregiving often relies on informal reciprocity networks, state social welfare departments formalize these arrangements into Village Care Committees that can coordinate home visits, emergency relief, and clinic referrals. To reinforce these structures, caregivers are registered as community health auxiliaries, gaining access to basic training, referral tools, and stipends. Local governments allocate microgrants to caregiver-led cooperatives that manage transport, nutrition, and medication logistics for dependent elders. Public recognition through caregiver ID cards and inclusion in local planning councils positions caregiving as a civic contribution with structural support.

- Promote flexibility in cultural and gendered caregiving expectations: Challenging traditional gender roles in caregiving requires coordinated action across education, media, and labor systems. Awareness campaigns and school-based programs can be helpful to normalize shared caregiving responsibilities across genders through storytelling, peer dialogue, and community theater that reshape expectations. The Ministry of Labor can extend family-friendly workplace policies, including flexible scheduling, paid elder-care leave, and caregiving tax credits. These provisions explicitly recognize elder care and incentivize male participation, repositioning caregiving as a collective social responsibility rather than a default burden assigned to women.

- Foster intergenerational relationships: Strengthening ties between generations requires more than promoting caregiving demands; it requires creating conditions where younger adults see long-term value in staying rooted. Local governments can offer land access, housing credits, or business incubation support to youth who co-reside with older relatives, linking caregiving to economic opportunity. Intergenerational apprenticeship programs allow elders to pass on vocational skills, cultural knowledge, and community leadership, positioning older adults as active contributors rather than passive recipients. Community cooperatives that include both youth and elders in decision-making, resource sharing, and local enterprise development reinforce mutual investment in place. These strategies reduce the economic and social pull of urban migration and rebuild intergenerational trust through shared purpose.

- Advocate for policy changes: Coordinated reform requires sustained collaboration across research, practice, and governance. Elder caregiving must be formally embedded within national health and social protection frameworks, supported by dedicated budget lines and measurable implementation targets. Nigeria currently lacks a central coordinating body for elder care policy. To fill this gap, a National Commission on Aging and Caregiving can be established to align efforts across health, labor, education, and finance sectors, elevating elder care from a peripheral welfare concern to a national development priority. A National Elder-Care Fund could allocate resources to enhance access to geriatric units in tertiary hospitals and finance mobile outreach services for home-bound elders. Caregivers’ leave policies are embedded in public sector employment codes and incentivized across private industries through tax relief and compliance credits. Inclusion of elder care in the National Health Insurance Scheme enables caregivers to enroll dependents and access subsidized services. Annual reporting on caregiver support benchmarks and equity outcomes ensures accountability and drives continuous improvement.

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization. Ageing and Health. 2022. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/ageing-and-health#:~:text=By%202030%2C%201%20in%206,will%20double%20(2.1%20billion) (accessed on 30 October 2025).

- International Monetary Fund. G20 Background Note on Aging Migration: Global Demographic Trends; IMF: Washington, DC, USA, 2025; Available online: https://www.imf.org/-/media/Files/Research/imf-and-g20/2025/G20-Background-Note-on-Aging-and-Migration.ashx (accessed on 20 October 2025).

- Wan, H. Increases in Africa’s Older Population Will Outstrip Growth in Any Other World Region. 2022. Available online: https://www.census.gov/library/stories/2022/04/why-study-aging-in-africa-region-with-worlds-youngest-population.html#:~:text=But%2C%20by%202050%2C%20the%20older,and%20approximating%20that%20of%20Europe (accessed on 15 July 2025).

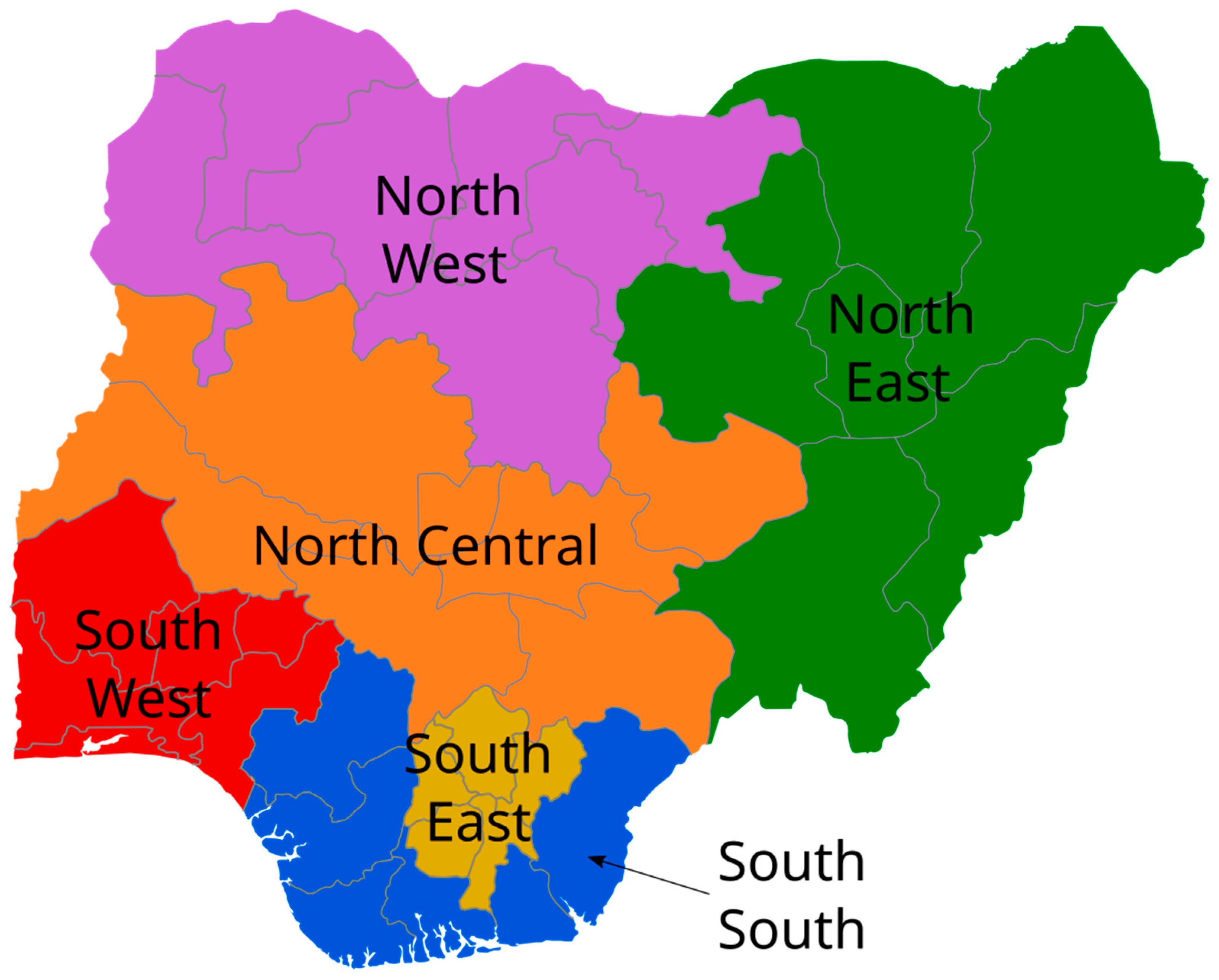

- Wikimedia Commons Contributors. Geopolitical Zones of Nigeria [Map]. Wikimedia Commons. Available online: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Geopolitical_Zones_of_Nigeria.svg (accessed on 31 October 2025).

- Population Reference Bureau. Countries with the Oldest Population in the World. 2020. Available online: https://www.prb.org/countries-with-the-oldest-populations/ (accessed on 15 July 2025).

- Ebimgbo, S.O.; Atama, C.S.; Igboeli, E.E.; Obi-Keguna, C.N.; Odo, C.O. Community versus family support in caregiving of older adults: Implications for social work practitioners in South-East Nigeria. Community Work Fam. 2022, 25, 152–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macrotrends. Nigeria Life Expectancy 1950–2023; macrotrends.net>NGA>life; Macrotrends: Seattle, WA, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Ebimgbo, S.O.; Chukwu, N.E.; Onalu, C.E.; Okoye, U.O. Perceived challenges associated with care of older adults by family caregivers and implications for social workers in South-east Nigeria. Indian J. Gerontol. 2019, 33, 160–177. [Google Scholar]

- Togonu-Bickersteth, F.; Akinyemi, A.I. Ageing and national development in Nigeria: Costly assumptions and challenges for the future. Afr. Popul. Stud. 2014, 27, 361–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agree, E.M. Demography of aging and the family. In Future Directions for the Demography of Aging: Proceedings of a Workshop; Hayward, M.D., Majmundar, M.K., Eds.; National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2018; pp. 159–186. [Google Scholar]

- Wiens, J.A. Population growth. Ecological challenges and conservation conundrums. Essays Reflect. Chang. World 2016, 75, 914–933. [Google Scholar]

- Yenilmez, M.I. Economic and social consequences of population aging the dilemmas and opportunities in the twenty-first century. Appl. Res. Qual. Life 2015, 10, 735–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ani, J.I. Care and support for the elderly in Nigeria: A review. Niger. J. Sociol. Anthropol. 2014, 12, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eboiyehi, F.A.; Onwuzuruigbo, I. Care and support for the aged among the Esan of South-South Nigeria. Niger. J. Sociol. Anthropol. 2014, 12, 44–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fajemilehin, B. Old age in a changing society: Elderly experiences of caregiving in Osun State, Nigeria. Afr. J. Nurs. Midwifery 2000, 2, 23–27. [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Ari, A.; Lavee, Y. Cultural orientation, ethnic affiliation, and negative daily occurrences: A multidimensional cross-cultural analysis. Am. J. Orthopsychiatry 2004, 74, 102–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCarty, C.A.; Weisz, J.R.; Wanitromanee, K.; Eastman, K.L.; Suwanlert, S.; Chaiyasit, W.; Band, E.B. Culture, coping, and context: Primary and secondary control among Thai and American youth. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry Allied Discip. 1999, 40, 809–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wahab, E.O.; Isiugo-Abanihe, U.C. Assessing the impact of old age security expectation on elderly persons’ achieved fertility in Nigeria. Indian J. Gerontol. 2010, 24, 357–378. [Google Scholar]

- Yankuzo, K.I. Impact of globalization on the traditional African cultures. Int. Lett. Soc. Humanist. Sci. 2014, 15, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Whittemore, R.; Knafl, K. The integrative review: Updated methodology. J. Adv. Nurs. 2005, 52, 546–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G.; PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. Ann. Intern. Med. 2009, 151, 264–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clarivate. EndNote, Version 2; Computer Software; Clarivate: London, UK, 2022. Available online: https://www.endnote.com (accessed on 30 November 2024).

- Carbado, D.W.; Crenshaw, K.W.; Mays, V.M.; Tomlinson, B. Intersectionality: Mapping the movements of a theory. Du Bois Rev. Soc. Sci. Res. Race 2013, 10, 303–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valentine, G. Theorizing and researching intersectionality: A challenge for feminist geography. Prof. Geogr. 2007, 59, 10–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abrams, J.A.; Tabaac, A.; Jung, S.; Else-Quest, N.M. Considerations for employing intersectionality in qualitative health research. Soc. Sci. Med. 2020, 258, 113–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauer, G.R. Incorporating intersectionality theory into population health research methodology: Challenges and the potential to advance health equity. Soc. Sci. Med. 2014, 110, 10–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, A. The Challenges of intersectionality in the lives of older adults living in rural areas with limited financial resources. Gerontol. Geriatr. Med. 2021, 7, 23337214211009363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lane, P.; Tribe, R.; Hui, R. Intersectionality and the mental health of elderly Chinese women living in the UK. Int. J. Migr. Health Soc. Care 2011, 6, 34–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sidloyi, S. Elderly, poor and resilient: Survival strategies of elderly women in female-headed households: An intersectionality perspective. J. Comp. Fam. Stud. 2016, 47, 379–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrard, J. Health Sciences Literature Review Made Easy: The Matrix Method, 5th ed.; Jones & Bartlett Learning: Burlington, MA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Baethge, C.; Goldbeck-Wood, S.; Mertens, S. SANRA—A scale for the quality assessment of narrative review articles. Res. Integr. Peer Rev. 2019, 4, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, Q.N.; Fàbregues, S.; Bartlett, G.; Boardman, F.; Cargo, M.; Dagenais, P.; Gagnon, M.P.; Griffiths, F.; Nicolau, B.; O’Cathain, A.; et al. The Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) version 2018 for information professionals and researchers. Educ. Inf. 2018, 34, 285–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pace, R.; Pluye, P.; Bartlett, G.; Macaulay, A.C.; Salsberg, J.; Jagosh, J.; Seller, R. Testing the reliability and efficiency of the pilot Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) for systematic mixed studies review. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2012, 49, 47–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, Q.; Pluye, P.; Fabregues, S.; Bartlett, G.; Boardman, F.; Cargo, M.; Dagenais, P.; Gagnon, M.P.; Griffiths, F.; Nicolau, B.; et al. Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT), Version 2018; McGill University Department of Family Medicine: Montreal, QC, Canada, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 5, 77–101. [Google Scholar]

- Daly, J.; Kellehear, A.; Gliksman, M. The Public Health Researcher: A Methodological Approach; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Akinrolie, O.; Okoh, A.C.; Kalu, M.E. Intergenerational support between older adults and adult children in Nigeria: The role of reciprocity. J. Gerontol. Soc. Work 2020, 63, 478–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ani, J.I.; Isiugo-Abanihe, U.C. Conditions of the elderly in selected areas in Nigeria. Int. J. Sociol. Fam. 2017, 43, 73–89. [Google Scholar]

- Namadi, M.M. Pattern of relationship between family caregivers and the elderly care recipients in Kano municipal local government area of Kano state, Nigeria. Glob. J. Appl. Manag. Soc. Sci. (GOJAMSS) 2016, 12, 60–66. [Google Scholar]

- Wahab, E.O.; Adedokun, A. Changing Family Structure and Care of the Older Persons in Nigeria; International Union for the Scientific Study of Population: Aubervilliers, France, 2012; Volume 25. [Google Scholar]

- Iwuagwu, A.O.; Ugwu, L.O.; Ugwuanyi, C.C.; Ngwu, C.N. Family caregivers’ awareness and perceived access to formal support care services available for older adults in Enugu State, Nigeria. Afr. J. Soc. Work 2022, 12, 12–20. [Google Scholar]

- Odaman, O.M.; Ibiezugbe, M.I. An empirical investigation of some social and economic remittances from relatives to the elderly Edo people. IFE Psychol. Int. J. 2014, 22, 64–71. [Google Scholar]

- Animasahun, V.J.; Chapman, H.J. Psychosocial health challenges of the elderly in Nigeria: A narrative review. Afr. Health Sci. 2017, 17, 575–583. [Google Scholar]

- Iwuagwu, A.O.; Ngwu, C.N.; Ekoh, C.P. Challenges of female older adults caring for their very old parents in rural Southeast Nigeria: A qualitative descriptive inquiry. J. Popul. Ageing 2022, 15, 907–923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanyi, P.L.; André, P.; Mbah, P. Care of the elderly in Nigeria: Implications for policy. Cogent Soc. Sci. 2018, 4, 1555201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shofoyeke, A.D.; Amosun, P.A. A survey of care and support for the elderly people in Nigeria. Mediterr. J. Soc. Sci. 2014, 5, 2553–2563. [Google Scholar]

- Mayston, R.; Lloyd-Sherlock, P.; Gallardo, S.; Wang, H.; Huang, Y.; Montes de Oca, V.; Prince, M. A journey without maps—Understanding the costs of caring for dependent older people in Nigeria, China, Mexico and Peru. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0182360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okoye, U.O. Family care-giving for ageing parents in Nigeria: Gender differences, cultural imperatives and the role of education. Int. J. Educ. Ageing 2012, 2, 139–154. [Google Scholar]

- Peil, M. Family support for the Nigerian elderly. J. Comp. Fam. Stud. 1991, 22, 85–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebimgbo, S.O.; Okoye, U.O. Challenges of left-behind older family members with international migrant children in south-east Nigeria. J. Popul. Ageing 2022, 17, 33–50. [Google Scholar]

- Peil, M.; Bamisaiye, A.; Ekpenyong, S. Health and physical support for the elderly in Nigeria. J. Cross-Cult. Gerontol. 1989, 4, 89–106. [Google Scholar]

- Ebimgbo, S.O.; Okoye, U.O. Perceived factors that predict the availability of social support when it is needed by older adults in Nnewi, South-East Nigeria. Niger. J. Soc. Sci. 2017, 13, 10–17. [Google Scholar]

- Ojifinni, O.O.; Uchendu, O.C. Experience of burden of care among adult caregivers of elderly persons in Oyo State, Nigeria: A cross-sectional study. Pan Afr. Med. J. 2022, 42, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mobolaji, J.W.; Akinyemi, A.I. Complementary support in later life: Investigating the gender disparities in patterns and determinants among older adults in South-Western Nigeria. BMC Geriatr. 2022, 22, 704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asuquo, E.F.; Etowa, J.B.; Akpan, M.I. Assessing women caregiving role to people living with HIV/AIDS in Nigeria, West Africa. SAGE Open 2017, 7, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asuquo, E.F.; Akpan-Idiok, P.A. The exceptional role of women as primary caregivers for people living with HIV/AIDS in Nigeria, West Africa. In Suggestions for Addressing Clinical and Non-Clinical Issues in Palliative Care; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guberman, N.; Maheu, P.; Maillé, C. Women as family caregivers: Why do they care? Gerontologist 1992, 32, 607–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalia, P.; Saini, S.; Vig, D. An appraisal of burden of stress among family caregivers of dependent elderly. Indian J. Health Wellbeing 2021, 12, 111–115. [Google Scholar]

- Schulz, R.; Eden, J. Family caregiving roles and impacts. In Families Caring for Aging America; Schulz, R., Eden, J., Eds.; The National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2016; pp. 73–122. [Google Scholar]

- Mpofu, L.; Moyo, I.; Mavhandu-Mudzusi, A.H. Caring for the elderly in the African context: An integrative review. Discov. Glob. Soc. 2025, 3, 127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oyegbile, Y.O. Informal caregiving: The lonely road traveled by caregivers in Africa. In Determinants of Loneliness; Ahmed, M.Z., Ed.; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mbam, K.C.; Halvorsen, C.J.; Okoye, U.O. Aging in Nigeria: A growing population of older adults requires the implementation of national aging policies. Gerontologist 2022, 62, 1243–1250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okoro, O. Long Distance International Caregiving to Elderly Parents Left Behind: Acase of Nigerian Adult Children Immigrants in USA. Ph.D. Thesis, University of North Texas, Denton, TX, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Jecker, N.S. Intergenerational ethics in Africa: Duties to older adults. Dev. World Bioeth. 2022, 22, 245–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hailu, G.N.; Gebru, H.B.; Hagos, G.G.; Weldemariam, A.H.; Tadesse, D.B.; Mebrahtom, G. The role of family caregivers in supporting older adults in Africa: A systematic review. BMC Geriatr. 2025, 25, 491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Federal Ministry of Humanitarian Affairs, Disaster Management and Social Development. National Policy on Ageing. 2023. Available online: https://fmhds.gov.ng/wp-content/uploads/2023/03/NATIONAL-POLICY-ON-AGEING-FMHADMSD-VERSION-1.pdf (accessed on 7 September 2025).

- Osi-Ogbu, O. Current status and the future trajectory of geriatric services in Nigeria. J. Glob. Med. 2024, 4, 229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikeorji, C.R.; Warria, A. Caregiving practices for older persons in Africa: Changing trends and implications for transformative social work. J. Soc. Dev. Afr. 2024, 39, 72–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Themes | Sub-Themes | Analytical Insights |

|---|---|---|

| Cultural Influences |

| Reflects the persistence of collectivist norms and intergenerational moral obligations shaping caregiving expectations. |

| Gender Differences |

| Reinforces gendered caregiving roles; highlights need for gender-sensitive policy. |

| Family Dynamics |

| Indicates strain on traditional systems; suggests need for formal care alternatives. |

| Economic Factors |

| Economic pressures reshape caregiving; urbanization may erode extended family support. |

| Caregiver Strain and Psychosocial Dimensions |

| Points to systemic gaps; underscores urgency for caregiver support programs. |

| Government Policies and Support |

| Reveals limited institutional frameworks for elder care, leaving families as the main support system. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Okigbo, C.S.; Freeman, S.; Hemingway, D.; Holler, J.; Schmidt, G. Patterns of Elder Caregiving Among Nigerians: An Integrative Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2026, 23, 2. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph23010002

Okigbo CS, Freeman S, Hemingway D, Holler J, Schmidt G. Patterns of Elder Caregiving Among Nigerians: An Integrative Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2026; 23(1):2. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph23010002

Chicago/Turabian StyleOkigbo, Chibuzo Stephanie, Shannon Freeman, Dawn Hemingway, Jacqueline Holler, and Glen Schmidt. 2026. "Patterns of Elder Caregiving Among Nigerians: An Integrative Review" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 23, no. 1: 2. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph23010002

APA StyleOkigbo, C. S., Freeman, S., Hemingway, D., Holler, J., & Schmidt, G. (2026). Patterns of Elder Caregiving Among Nigerians: An Integrative Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 23(1), 2. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph23010002