Updating Health Canada’s Heat-Health Messages for the Environment and Climate Change Canada Heat Warning System: A Collaboration with Canadian Experts

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

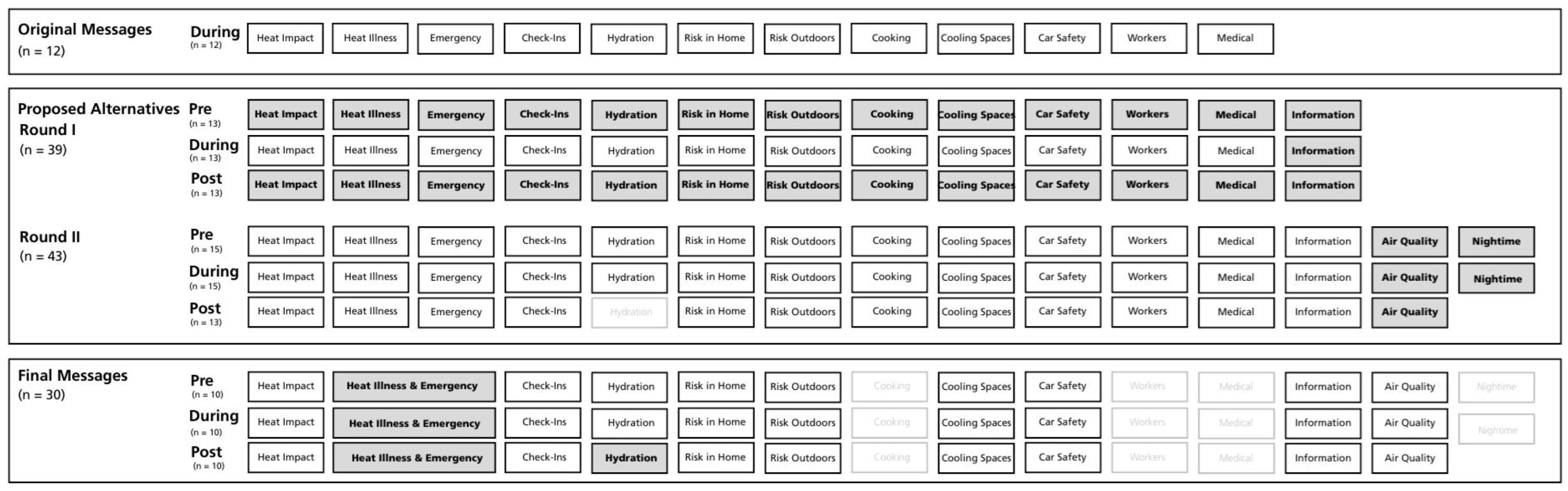

2.1. Developing the Revised Messaging

2.2. Developing the Assessment Instrument

2.3. Conducting External Expert Review: Round I and II

2.4. Data Analysis

2.4.1. Descriptive Statistics

2.4.2. Text-Based Analysis

2.4.3. Readability Assessment

2.5. Final Revisions and Application in the Weather Warning System

3. Results

3.1. Expert Reviewer Descriptors

3.2. Ranking Agreement and Inclusion

3.3. Alignment with the Critical Elements of Risk Communication

3.3.1. Important

3.3.2. Action-Oriented

3.3.3. Evidence-Based

3.3.4. Readability

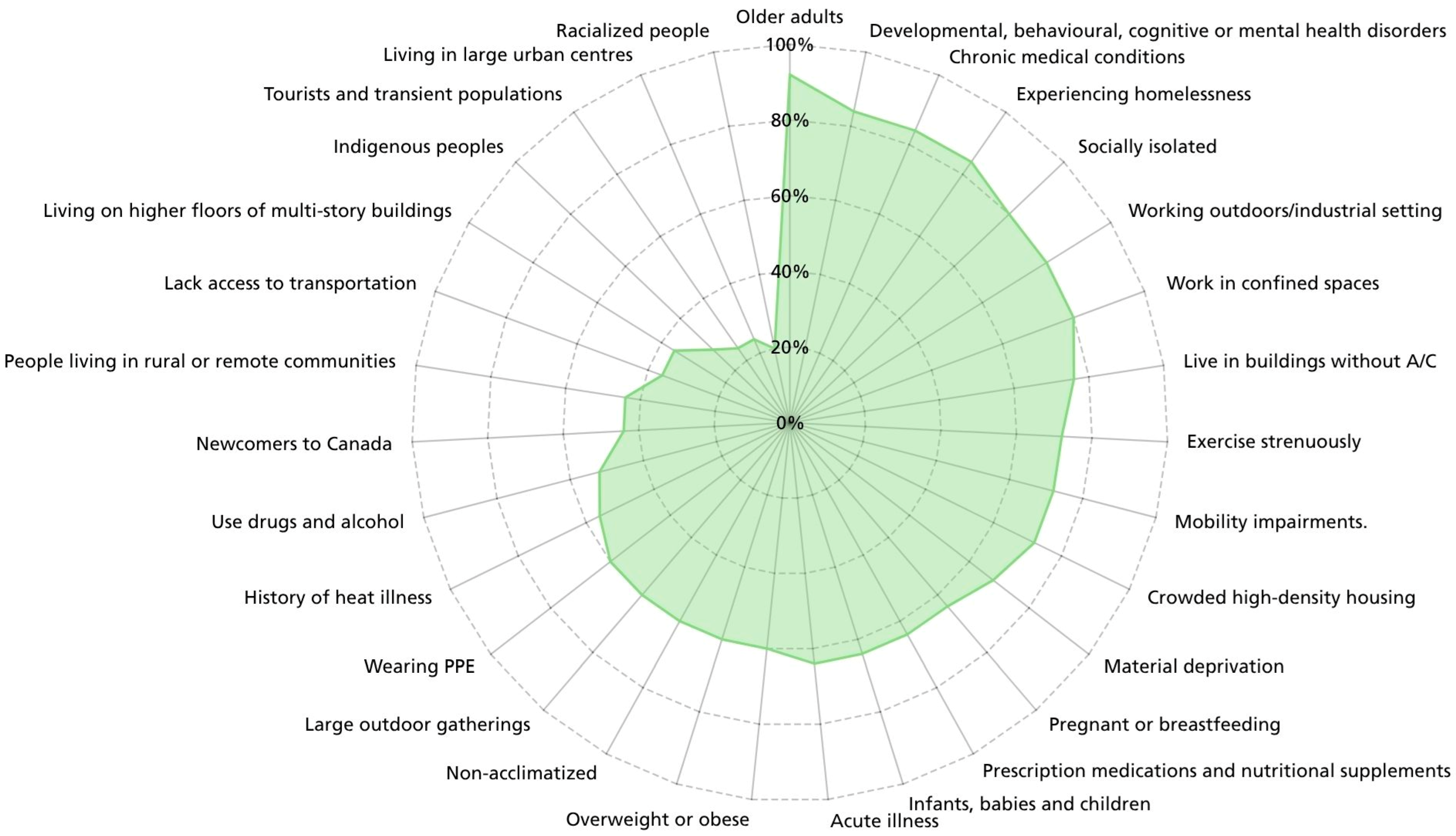

3.3.5. Equity

3.3.6. Regional Applicability

3.4. Finalized Messages

4. Discussion

4.1. Important, Action-Oriented and Evidence-Based

4.2. Readability, Equity and Regional Applicability

4.3. Strengths and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ECCC | Environment and Climate Change Canada |

| HARS | Heat Alert and Response System(s) |

| SMOG | Simplified Measure of Gobbledygook |

| FRE | Flesch Reading Ease |

| FKGL | Flesch–Kincaid Grade Level |

| ARI | Automated Readability Index |

| GFI | Gunning Fog Index |

References

- Gosselin, P.; Campagna, C.; Demers-Bouffard, D.; Qutob, S.; Flannigan, M. Natural Hazards. In Health of Canadians in a Changing Climate: Advancing Our Knowledge for Action; Government of Canada: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Berry, P.; Enright, P.; Varangu, L.; Singh, S.; Campagna, C.; Gosselin, P.; Demers-Bouffard, D.; Thomson, D.; Ribesse, J.; Elliott, S. Adaptation and Health System Resilience. In Health of Canadians in a Changing Climate: Advancing Our Knowledge for Action; Government of Canada: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Health Canada. Heat Alert and Response Systems to Protect Health: Best Practices Guidebook; Health Canada: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2012.

- Grothmann, T.; Leitner, M.; Glas, N.; Prutsch, A. A Five-Steps Methodology to Design Communication Formats That Can Contribute to Behavior Change: The Example of Communication for Health-Protective Behavior Among Elderly During Heat Waves. SAGE Open 2017, 7, 215824401769201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Issa, M.A.; Chebana, F.; Masselot, P.; Campagna, C.; Lavigne, É.; Gosselin, P.; Ouarda, T.B.M.J. A Heat-Health Watch and Warning System with Extended Season and Evolving Thresholds. BMC Public Health 2021, 21, 1479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenny, G.; Tetzlaff, E.; Journeay, W.; Henderson, S.; O’Connor, F. Indoor Overheating: A Review of Vulnerabilities, Causes, and Strategies to Prevent Adverse Human Health Outcomes during Extreme Heat Events. Temperature 2024, 11, 203–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- British Columbia Coroners Service. Extreme Heat and Human Mortality: A Review of Heat-Related Deaths in B.C. in Summer 2021; British Columbia Coroners Service: British Columbia, BC, Canada, 2022; p. 56.

- Tetzlaff, E.; Wagar, K.; Johnson, S.; Gorman, M.; Kenny, G. Heat-Health Messaging in Canada: A Review and Content Analysis of Public Health Authority Webpages and Resources. Public Health Pract. 2024, 9, 100576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, W.; Li, D.; Liu, Z.; Brown, R.D. Approaches for Identifying Heat-Vulnerable Populations and Locations: A Systematic Review. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 799, 149417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gil-Cuesta, J.; van Loenhout, J.; Colaço, M.; Guha-Sapir, D. General Population Knowledge about Extreme Heat: A Cross-Sectional Survey in Lisbon and Madrid. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2017, 14, 122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varickanickal, J.; Newbold, K.B. Extreme Heat Events and Health Vulnerabilities among Immigrant and Newcomer Populations. Environ. Health Rev. 2021, 64, 28–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Health Canada. Communicating the Health Risks of Extreme Heat Events: Toolkit for Public Health and Emergency Management Officials; Health Canada: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2011; ISBN 978-1-100-17344-3.

- Gronlund, C.J. Racial and Socioeconomic Disparities in Heat-Related Health Effects and Their Mechanisms: A Review. Curr. Epidemiol. Rep. 2014, 1, 165–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heger, M. Equitable Adaptation to Extreme Heat Impacts of Climate Change. J. Environ. Law Policy 2022, 39, 283–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Environment and Climate Change Canada. Canada’s Changing Climate Report; Bush, Lemmen, Eds.; Government of Canada: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2019; ISBN 978-0-660-30222-5.

- Von Elm, E.; Altman, D.G.; Egger, M.; Pocock, S.J.; Gøtzsche, P.C.; Vandenbroucke, J.P. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) Statement: Guidelines for Reporting Observational Studies. Lancet 2007, 370, 1453–1457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGowan, J.; Sampson, M.; Salzwedel, D.M.; Cogo, E.; Foerster, V.; Lefebvre, C. PRESS Peer Review of Electronic Search Strategies: 2015 Guideline Statement. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2016, 75, 40–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garritty, C.; Gartlehner, G.; Nussbaumer-Streit, B.; King, V.J.; Hamel, C.; Kamel, C.; Affengruber, L.; Stevens, A. Cochrane Rapid Reviews Methods Group Offers Evidence-Informed Guidance to Conduct Rapid Reviews. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2021, 130, 13–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- MacIntyre, E.; Khanna, S.; Darychuk, A.; Copes, R.; Schwartz, B. Evidence Synthesis—Evaluating Risk Communication during Extreme Weather and Climate Change: A Scoping Review. Health Promot. Chronic Dis. Prev. Can. 2019, 39, 142–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fitzpatrick-Lewis, D.; Yost, J.; Ciliska, D.; Krishnaratne, S. Communication about Environmental Health Risks: A Systematic Review. Environ. Health 2010, 9, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reynolds, B.J. When the Facts Are Just Not Enough: Credibly Communicating about Risk Is Riskier When Emotions Run High and Time Is Short. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2011, 254, 206–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabinovich, A.; Morton, T.A. Unquestioned Answers or Unanswered Questions: Beliefs About Science Guide Responses to Uncertainty in Climate Change Risk Communication. Risk Anal. 2012, 32, 992–1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akompab, D.A.; Bi, P.; Williams, S.; Grant, J.; Walker, I.A.; Augoustinos, M. Heat Waves and Climate Change: Applying the Health Belief Model to Identify Predictors of Risk Perception and Adaptive Behaviours in Adelaide, Australia. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2013, 10, 2164–2184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenman, D.P.; Cordasco, K.M.; Asch, S.; Golden, J.F.; Glik, D. Disaster Planning and Risk Communication With Vulnerable Communities: Lessons From Hurricane Katrina. Am. J. Public Health 2007, 97, S109–S115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pidgeon, N.; Fischhoff, B. The Role of Social and Decision Sciences in Communicating Uncertain Climate Risks. Nat. Clim. Change 2011, 1, 35–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badarudeen, S.; Sabharwal, S. Assessing Readability of Patient Education Materials: Current Role in Orthopaedics. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 2010, 468, 2572–2580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedman, D.B.; Hoffman-Goetz, L. An Exploratory Study of Older Adults’ Comprehension of Printed Cancer Information: Is Readability a Key Factor? J. Health Commun. 2007, 12, 423–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLaughlin, G.H. SMOG Grading-a New Readability Formula. J. Read. 2023, 12, 639–646. [Google Scholar]

- Flesch, R. A Readability Formula In Practice. Natl. Counc. Teach. Engl. 1948, 25, 344–351. [Google Scholar]

- Kincaid, J.P.; Fishburne, R.P., Jr.; Rogers, R.L.; Chissom, B.S. Derivation of New Readability Formulas (Automated Readability Index, Fog Count and Flesch Reading Ease Formula) for Navy Enlisted Personnel; Defense Technical Information Center: Fort Belvoir, VA, USA, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Gunning, R. The Technique of Clear Writing; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1952. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, L.-W.; Miller, M.J.; Schmitt, M.R.; Wen, F.K. Assessing Readability Formula Differences with Written Health Information Materials: Application, Results, and Recommendations. Res. Soc. Adm. Pharm. 2013, 9, 503–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boutemen, L.; Miller, A.N. Readability of Publicly Available Mental Health Information: A Systematic Review. Patient Educ. Couns. 2023, 111, 107682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delaney, F.T.; Doinn, T.Ó.; Broderick, J.M.; Stanley, E. Readability of Patient Education Materials Related to Radiation Safety: What Are the Implications for Patient-Centred Radiology Care? Insights Imaging 2021, 12, 148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freed, K.; Taylor, M.G.; Toledo, P.; Kruse, J.H.; Palanisamy, A.; Lange, E.M.S. Readability, Content, and Quality of Online Patient Education Materials on Anesthesia and Neurotoxicity in the Pediatric Population. Am. J. Perinatol. 2022, 41, e341–e347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parmar, G.S.; Das, S.; Ingledew, P.-A. Quality of Online Information for Esophageal Cancer. J. Canc. Educ. 2022, 38, 863–869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Serry, T.; Stebbins, T.; Martchenko, A.; Araujo, N.; McCarthy, B. Improving Access to COVID-19 Information by Ensuring the Readability of Government Websites. Health Prom. J. Aust. 2022, 34, 595–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crossley, S.; Heintz, A.; Choi, J.S.; Batchelor, J.; Karimi, M.; Malatinszky, A. A Large-Scaled Corpus for Assessing Text Readability. Behav. Res. 2022, 55, 491–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bailin, A.; Grafstein, A. Readability: Text and Context; Palgrave Macmillan UK: London, UK, 2016; ISBN 978-1-349-57055-3. [Google Scholar]

- Health Canada Research Ethics Board: Policies, Guidelines and Resources. In Health Science and Research; Government of Canada: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2023.

- National Institute of Health Clear Communication: How to Write Easy-to-Read Health Materials. Available online: https://www.nih.gov/institutes-nih/nih-office-director/office-communications-public-liaison/clear-communication/clear-simple (accessed on 29 January 2024).

- Paasche-Orlow, M.K.; Taylor, H.A.; Brancati, F.L. Readability Standards for Informed-Consent Forms as Compared with Actual Readability. N. Engl. J. Med. 2003, 348, 721–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paasche-Orlow, M.K.; Parker, R.M.; Gazmararian, J.A.; Nielsen-Bohlman, L.T.; Rudd, R.R. The Prevalence of Limited Health Literacy. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2005, 20, 175–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weis, B. Health Literacy: A Manual for Clinicians; American Medical Association Foundation and American Medical Association: Chicago, IL, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Sheridan, S.C. A Survey of Public Perception and Response to Heat Warnings across Four North American Cities: An Evaluation of Municipal Effectiveness. Int. J. Biometeorol. 2007, 52, 3–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rooney, M.K.; Santiago, G.; Perni, S.; Horowitz, D.P.; McCall, A.R.; Einstein, A.J.; Jagsi, R.; Golden, D.W. Readability of Patient Education Materials From High-Impact Medical Journals: A 20-Year Analysis. J. Patient Exp. 2021, 8, 237437352199884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tetzlaff, E.J.; Janetos, K.M.T.; Wagar, K.E.; Mourad, F.; Gorman, M.; Gallant, V.; Kenny, G.P. Assessing the Language Availability, Readability, Suitability and Comprehensibility of Heat-Health Messaging Content on Health Authority Webpages and Online Resources in Canada. PEC Innov. 2024, 6, 100368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tetzlaff, E.J.; Mourad, F.; Goulet, N.; Gorman, M.; Siblock, R.; Kidd, S.A.; Bezgrebelna, M.; Kenny, G.P. “Death Is a Possibility for Those without Shelter”: A Thematic Analysis of News Coverage on Homelessness and the 2021 Heat Dome in Canada. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2024, 21, 405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, L.; Tetzlaff, E.J.; Wong, C.; Chiu, T.; Hiscox, L.; Mew, S.; Choquette, D.; Kenny, G.P.; Schütz, C.G. Responding to the Heat and Planning for the Future: An Interview-Based Inquiry of People with Schizophrenia Who Experienced the 2021 Heat Dome in Canada. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2024, 21, 1108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tetzlaff, E.J.; Goulet, N.; Gorman, M.; Kenny, G.P. The combined impacts of toxic drug use and the 2021 Heat Dome in Canada: A thematic analysis of online news media articles. PLoS ONE 2025, 20, e0318229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Ranking | Agreement with Modifications | Inclusion in the ECCC Warning System | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Messages | Avg ± SD Median Range | Yes n (%) | Unsure n (%) | No n (%) | Yes n (%) | Unsure n (%) | No n (%) |

| Message 1 Heat Impact | 5th ± 5 2nd 1st–15th | 24 (83%) | 1 (3%) | 4 (14%) | 25 (86%) | 3 (10%) | 1 (3%) |

| Message 2 Heat Illness | 3rd ± 2 2nd 1st–11th | 23 (79%) | 1 (3%) | 5 (17%) | 26 (90%) | 3 (10%) | 0 (0%) |

| Message 3 Emergency | 5th ± 4 4th 1st–15th | 22 (76%) | 2 (7%) | 5 (17%) | 23 (79%) | 4 (14%) | 2 (7%) |

| Message 4 Check-Ins | 4th ± 2 4th 1st–9th | 23 (79%) | 3 (10%) | 3 (10%) | 26 (90%) | 2 (7%) | 1 (3%) |

| Message 5 Hydration | 6th ± 3 5th 1st–13th | 23 (79%) | 3 (10%) | 3 (10%) | 25 (86%) | 4 (14%) | 0 (0%) |

| Message 6 Risk in Home | 8th ± 3 7th 3rd–14th | 22 (76%) | 4 (14%) | 3 (10%) | 20 (69%) | 7 (24%) | 2 (7%) |

| Message 7 Risk Outdoors | 7th ± 3 7th 2nd–14th | 26 (90%) | 1 (3%) | 2 (7%) | 26 (90%) | 1 (3%) | 2 (7%) |

| Message 10 Car Safety | 7th ± 4 7th 2nd–15th | 26 (90%) | 1 (3%) | 2 (7%) | 24 (83%) | 3 (10%) | 2 (7%) |

| Message 9 Cooling Spaces | 10th ± 3 9th 4th–15th | 24 (83%) | 1 (3%) | 4 (14%) | 24 (80%) | 3 (10%) | 3 (10%) |

| Message 15 Nighttime | 10th ± 2 10th 6th–13th | 21 (75%) | 5 (18%) | 2 (7%) | 24 (83%) | 3 (10%) | 2 (7%) |

| Message 13 Information | 9th ± 5 10th 1st–15th | 24 (83%) | 3 (10%) | 2 (7%) | 28 (97%) | 1 (3%) | 0 (0%) |

| Message 11 Workers | 10th ± 3 10.5th 3rd–15th | 25 (86%) | 0 (0%) | 4 (14%) | 21 (72%) | 3 (10%) | 5 (17%) |

| Message 14 Air Quality | 11th ± 3 11th 3rd–15th | 18 (64%) | 5 (18%) | 5 (18%) | 21 (72%) | 5 (17%) | 3 (10%) |

| Message 12 Medical | 11th ± 3 11.5th 5th–15th | 27 (93%) | 1 (3%) | 1 (3%) | 21 (72%) | 3 (10%) | 5 (17%) |

| Message 8 Cooking | 13th ± 3 13th 4th–15th | 26 (90%) | 0 (0%) | 3 (10%) | 17 (59%) | 4 (14%) | 8 (28%) |

| Yes n (%) | Some n (%) | No n (%) | Change in Response n (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Importance | Are the proposed messages important for the ECCC weather warning system? | ||||

| Review Round I Review Round II | 20 (74%) 17 (59%) | 7 (26%) 12 (41%) | 0 (0%) 0 (0%) | ≡11 (74%) +2 (13%) -2 (13%) | |

| Are the proposed messages important at the time points indicated (preheat event, during, post-event)? | |||||

| Review Round I Review Round II | 15 (56%) 24 (83%) | 10 (37%) 5 (17%) | 1 (4%) 0 (0%) | ≡6 (40%) +7 (47%) -2 (13%) | |

| Action-Orientation | Are the proposed messages sufficiently action-oriented? | ||||

| Review Round I Review Round II | 15 (56%) 21 (72%) | 12 (44%) 8 (28%) | 0 (0%) 0 (0%) | ≡11 (74%) +4 (27%) -0 (0%) | |

| Are the proposed messages appropriate to action at the time points indicated? | |||||

| Review Round I Review Round II | 15 (56%) 25 (86%) | 11 (41%) 4 (14%) | 1 (4%) 0 (0%) | ≡8 (53%) +6 (40%) -1 (7%) | |

| Evidence Base | Are the proposed messages evidence-based? | ||||

| Review Round I Review Round II | 19 (73%) 18 (62%) | 5 (19%) 11 (38%) | 1 (4%) 0 (0%) | ≡12 (80%) +1 (7%) -2 (13%) | |

| Where applicable, do the proposed messages include the necessary conditional disclaimers needed? | |||||

| Review Round I Review Round II | 13 (48%) 17 (61%) | 13 (48%) 10 (36%) | 0 (0%) 1 (4%) | ≡12 (80%) +1 (7%) -2 (13%) | |

| Readability | Are the proposed messages written at a reading grade level appropriate for the public? | ||||

| Review Round I Review Round II | 18 (67%) 20 (69%) | 9 (33%) 7 (24%) | 0 (%) 2 (7%) | ≡9 (60%) +4 (27%) -2 (13%) | |

| Are the proposed messages free of jargon or complex terms? | |||||

| Review Round I Review Round II | 16 (59%) 24 (83%) | 11 (41%) 4 (14%) | 0 (0%) 1 (3%) | ≡6 (40%) +8 (53%) -1 (7%) | |

| Equity | Are the proposed messages equitable? | ||||

| Review Round I Review Round II | 17 (63%) 16 (55%) | 8 (30%) 13 (45%) | 2 (7%) 0 (0%) | ≡10 (67%) +2 (13%) -3 (20%) | |

| Do the proposed messages provide heat-protective measures that are feasible for individuals of various socio-economic backgrounds? | |||||

| Review Round I Review Round II | 16 (59%) 18 (62%) | 9 (33%) 10 (34%) | 2 (7%) 1 (3%) | ≡9 (60%) +4 (27%) -2 (13%) | |

| Applicability | Are the proposed messages applicable to your geographic region? | ||||

| Review Round I Review Round II | 23 (85%) 21 (75%) | 4 (15%) 7 (25%) | 0 (0%) 0 (0%) | ≡11 (74%) +2 (13%) -2 (13%) | |

| Are the proposed messages appropriately reflective of various climate conditions in Canada? | |||||

| Review Round I Review Round II | 18 (67%) 19 (70%) | 8 (30%) 8 (30%) | 1 (4%) 0 (0%) | ≡12 (80%) +3 (20%) -0 (0%) | |

| Original Message | Final Message | |

|---|---|---|

| Message 1: Extreme heat affects everyone. The risks are greater for young children, pregnant women, older adults, people with chronic illnesses and people working or exercising outdoors. | ✓ | Pre: Extreme heat can affect everyone’s health. Determine if you or others around you are at greater risk of heat illness. |

| ✓ | During: Take action to protect yourself and others—extreme heat can affect everyone’s health. Determine if you or others around you are at greater risk of heat illness such as older adults, people with chronic disease, and those who are socially isolated. | |

| ✓ | Post: Take precautions to reduce your risk of heat illness, as it may develop after the heat event is over. Continue to check yourself and others for signs. | |

| Message 2: Watch for the symptoms of heat illness: dizziness/fainting; nausea/vomiting; rapid breathing and heartbeat; extreme thirst; decreased urination with unusually dark urine. | 🗶 | Merged. |

| Message 3: Heat stroke is a medical emergency! Call 911 or your local emergency number immediately if you are caring for someone, such as a neighbour, who has a high body temperature and is either unconscious, confused or has stopped sweating. While waiting for help—cool the person right away by: moving them to a cool place, if you can; applying cold water to large areas of the skin or clothing; and fanning the person as much as possible. | ✓ | Pre: Be aware of the early signs of heat exhaustion in yourself and others it can rapidly become a life-threatening emergency like heat stroke. Heat can cause dehydration and heat exhaustion, including swelling, rash, cramps, fainting, and worsening of pre-existing health conditions. Heat stroke is a medical emergency. |

| ✓ | During: Watch for the early signs of heat exhaustion in yourself and others. Signs may include headache, nausea, dizziness, thirst, dark urine and intense fatigue. Stop your activity and drink water. Heat stroke is a medical emergency! Call 9-1-1 or your emergency health provider if you, or someone around you, is showing signs of heat stroke which can include red and hot skin, dizziness, nausea, confusion and change in consciousness. While you wait for medical attention, try to cool the person by moving them to a cool place, removing extra clothing, applying cold water or ice packs around the body. | |

| ✓ | Post: Continue to monitor yourself and others for signs of heat exhaustion and heat stroke. The effects of heat can continue to be experienced even after an extreme heat event is over. | |

| Message 4: Check on older family, friends and neighbours. Make sure they are cool and drinking water. | ✓ | Pre: Talk to family, friends and neighbours to see how they are preparing for the heat. Create a plan to support each other and check in multiple times a day with those at greater risk. |

| ✓ | During: Check on older adults, those living alone and other at-risk people in-person or on the phone multiple times a day. | |

| ✓ | Post: Check in on older adults, those living alone and other at-risk people in-person or on the phone, for a few days after the heat event ends, as it can remain hot indoors. | |

| Message 5: Drink plenty of cool liquids, especially water, before you feel thirsty to decrease your risk of dehydration. Thirst is not a good indicator of dehydration. | ✓ | Pre: Drink water often to avoid dehydration. Dehydration can lead to a heat illness. |

| ✓ | During: Drink water often and before you feel thirsty to replace fluids. Exposure to heat will cause your body to lose fluids through sweat. | |

| ✓ | Post: Continue to drink water to stay hydrated as the heat may remain high. | |

| Message 6: Keep your house cool. Block the sun by closing curtains or blinds. | ✓ | Pre: Find ways to keep your living space cool and make sure air-conditioning, fans, and windows are working. |

| ✓ | During: Close blinds, or shades and open windows if outside is cooler than inside. Turn on air conditioning, use a fan, or move to a cooler area of your living space. | |

| ✓ | Post: The temperature of your living space can remain high even after a heat event is over. Continue to stay cool by opening windows and using a fan to move cool air indoors. | |

| Message 7: Avoid sun exposure. Shade yourself by wearing a wide-brimmed, breathable hat or using an umbrella. | ✓ | Pre: Plan and schedule outdoor activities during the coolest parts of the day or reschedule them until the heat event has passed. If outdoors, seek shaded areas. |

| ✓ | During: Plan and schedule outdoor activities during the coolest parts of the day. Limit direct exposure to the sun and heat. Wear lightweight, light-coloured, loose-fitting clothing and a wide-brimmed hat. | |

| ✓ | Post: Be careful outdoors as it remains hot. | |

| Message 8: When it’s hot eat cool, light meals. | 🗶 | Removed. |

| Message 9: Seek a cool place such as a tree-shaded area, swimming pool, shower or bath, or air-conditioned spot like a public building. | ✓ | Pre: Find air-conditioned or cool spots in your area where you can go such as community centre, library, stores or shaded park. Plan for help with transport if needed. |

| ✓ | During: Move to a cool public space such as a cooling centre, community centre, library or shaded park if your living space is hot. | |

| ✓ | Post: Monitor your living space and keep cool as needed. It can still be hot inside even after a heat event is over. | |

| Message 10: Never leave people or pets inside a parked vehicle. | ✓ | Pre: Never leave people, especially children, or pets inside a parked vehicle. Check the vehicle before locking it to make sure no one is left behind. |

| ✓ | During: Never leave people, especially children, or pets inside a parked vehicle. Check the vehicle before locking to make sure no one is left behind. | |

| ✓ | Post: Never leave people, especially children, or pets inside a parked vehicle. Check the vehicle before locking it to make sure no one is left behind. | |

| Message 11: Outdoor workers should take regularly scheduled breaks in a cool place. | 🗶 | Removed. |

| Message 12: Ask a health professional how medications or health conditions can affect your risk in the heat. | 🗶 | Removed. |

| Message 13: N/A | ✓ | Pre: Be aware of advice and resources from local and public health authorities that can help you stay cool and safe from the heat. |

| ✓ | During: Check heat alerts via the Public Weather Alerts website or the WeatherCAN app. Follow the advice of your region’s public health authority. | |

| ✓ | Post: Keep helpful contacts and heat-health web links to be prepared for the next heat event. | |

| Message 14: N/A | ✓ | Pre: When there is an extreme heat event occurring with wildfire smoke, prioritize keeping cool. |

| ✓ | During: When there is an extreme heat event occurring with wildfire smoke, prioritize keeping cool. | |

| ✓ | Post: If air quality has improved, open windows and doors to move cool air into the space at night, if safe. | |

| Message 15: N/A | 🗶 | Removed. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tetzlaff, E.J.; MacDonald, M.; Kenny, G.P.; Murphy, B.; Siblock, R.F.; Al-Hertani, A.; Stranberg, R.C.; Berry, P.; Gorman, M. Updating Health Canada’s Heat-Health Messages for the Environment and Climate Change Canada Heat Warning System: A Collaboration with Canadian Experts. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2025, 22, 1266. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22081266

Tetzlaff EJ, MacDonald M, Kenny GP, Murphy B, Siblock RF, Al-Hertani A, Stranberg RC, Berry P, Gorman M. Updating Health Canada’s Heat-Health Messages for the Environment and Climate Change Canada Heat Warning System: A Collaboration with Canadian Experts. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2025; 22(8):1266. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22081266

Chicago/Turabian StyleTetzlaff, Emily J., Melissa MacDonald, Glen P. Kenny, Brittany Murphy, Rachel F. Siblock, Ahmed Al-Hertani, Rebecca C. Stranberg, Peter Berry, and Melissa Gorman. 2025. "Updating Health Canada’s Heat-Health Messages for the Environment and Climate Change Canada Heat Warning System: A Collaboration with Canadian Experts" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 22, no. 8: 1266. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22081266

APA StyleTetzlaff, E. J., MacDonald, M., Kenny, G. P., Murphy, B., Siblock, R. F., Al-Hertani, A., Stranberg, R. C., Berry, P., & Gorman, M. (2025). Updating Health Canada’s Heat-Health Messages for the Environment and Climate Change Canada Heat Warning System: A Collaboration with Canadian Experts. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 22(8), 1266. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22081266