Self-Management at Work’s Moderating Effect on the Relations Between Psychosocial Work Factors and Well-Being

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Theoretical Models and Literature Review

1.1.1. Psychosocial Work Factors and Well-Being

1.1.2. Mental Health Self-Management (MHS)

1.1.3. Mental Health Self-Management at Work

1.2. Research Gap and Contributions

1.3. Objectives and Hypotheses

- To investigate the relationship between psychosocial work factors and both positive and negative well-being indicators.

- To explore the association between self-management at work and well-being, as well as the moderating role of self-management at work in mitigating the deleterious effects of psychosocial work factors on well-being.

2. Methods

2.1. Research Design

2.2. Participants

2.3. Measures

2.4. Procedure

2.5. Data Analysis

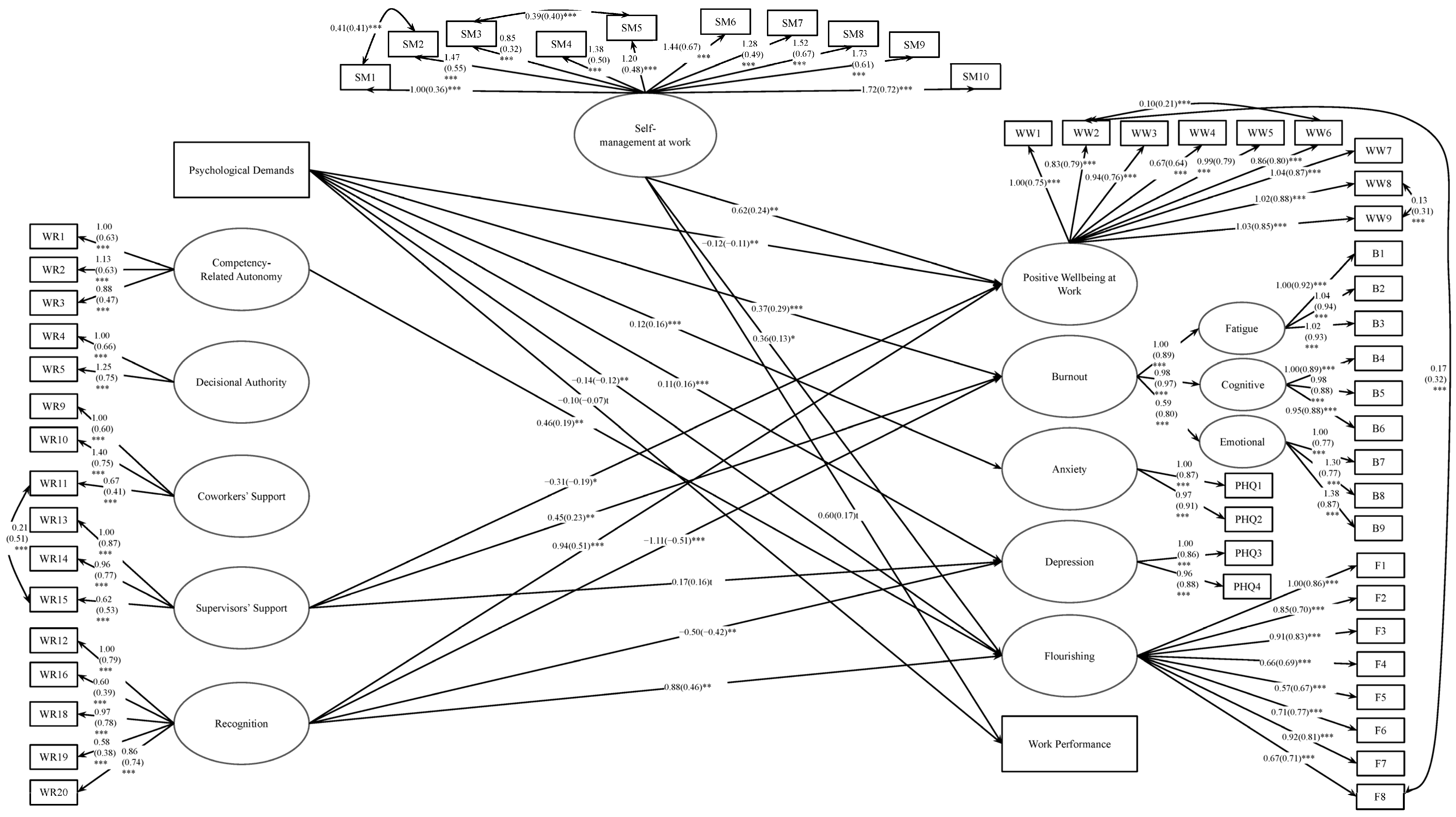

3. Results

3.1. Preliminary Analyses and Descriptive Statistics

3.2. Main Analyses

Moderation Analyses

4. Discussion

4.1. Practical Implications

4.2. Limitations

4.3. Future Research Directions

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Greenwood, K.; Anas, J. It’s a new era for mental health at work. Harvard Business Review, 24 October 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Lebeau, M.; Bilodeau, J.; Busque, M.-A. Le Coût des Lésions Psychologiques Liées au Travail au Québec; R-1196-fr; Institut de Recherche Robert-Sauvé en Santé et Sécurité du Travail—Institut National de Santé Publique du Québec et Institut de la Statistique du Québec: Montréal, QC, Canada, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Monroe, C.; Loresto, F.; Horton-Deutsch, S.; Kleiner, C.; Eron, K.; Varney, R.; Grimm, S. The value of intentional self-care practices: The effects of mindfulness on improving job satisfaction, teamwork, and workplace environments. Arch. Psychiatr. Nurs. 2021, 35, 189–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schaufeli, W.B.; Bakker, A.B.; Van Rhenen, W. How changes in job demands and resources predict burnout, work engagement, and sickness absenteeism. J. Organ. Behav. 2009, 30, 893–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, T.A.; Bonett, D.G. Job satisfaction and psychological well-being as nonadditive predictors of workplace turnover. J. Manag. 2007, 33, 141–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A.B.; Demerouti, E.; Sanz-Vergel, A. Job Demands–Resources Theory: Ten Years Later. Annu. Rev. Organ. Psychol. Organ. Behav. 2023, 10, 25–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demerouti, E.; Bakker, A.B. Job demands-resources theory in times of crises: New propositions. Organ. Psychol. Rev. 2022, 13, 209–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leka, S.; Jain, A.; Lerouge, L. Work-related psychosocial risks: Key definitions and an overview of the policy context in Europe. In Psychosocial Risks in Labour and Social Security Law: A Comparative Legal Overview from Europe, North America, Australia and Japan; Lerouge, L., Ed.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niedhammer, I.; Goldberg, M.; Leclerc, A.; Bugel, I.; David, S. Psychosocial factors at work and subsequent depressive symptoms in the Gazel cohort. Scand. J. Work. Environ. Health 1998, 24, 197–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rich, B.L.; Lepine, J.A.; Crawford, E.R. Job engagement: Antecedents and effects on job performance. Acad. Manag. J. 2010, 53, 617–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vézina, M.; Cloutier, E.; Stock, S.; Lippel, K.; Fortin, É.; Delisle, A.; St-Vincent, M.; Funes, A.; Duguay, P.; Vézina, S.; et al. Enquête Québécoise sur des Conditions de Travail, d’Emploi et de Santé et de Sécurité du Travail (EQCOTESST); Institut de Recherche Robert-Sauvé en Santé et Sécurité du Travail—Institut National de Santé Publique du Québec et Institut de la Statistique du Québec: Montréal, QC, Canada, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Niedhammer, I.; Bertrais, S.; Witt, K. Psychosocial work exposures and health outcomes: A meta-review of 72 literature reviews with meta-analysis. Scand. J. Work. Environ. Health 2021, 47, 489–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailey, C.; Yeoman, R.; Madden, A.; Thompson, M.; Kerridge, G. A Review of the empirical literature on meaningful work: Progress and research agenda. Hum. Resour. Dev. Rev. 2019, 18, 83–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barros, C.; Fonte, C.; Alves, S.; Baylina, P. Can psychosocial work factors influence psychologists’ positive mental health? Occup. Med. 2019, 69, 204–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, J.K.; Mustard, C.; Smith, P.M. Psychosocial Work Conditions and Mental Health: Examining Differences Across Mental Illness and Well-Being Outcomes. Ann. Work Expo. Health 2019, 63, 546–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Finne, L.B.; Christensen, J.O.; Knardahl, S. Psychological and social work factors as predictors of mental distress and positive affect: A prospective, multilevel study. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0152220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- LaMontagne, A.D.; Milner, A.; Krnjacki, L.; Schlichthorst, M.; Kavanagh, A.; Page, K.; Pirkis, J. Psychosocial job quality, mental health, and subjective wellbeing: A cross-sectional analysis of the baseline wave of the Australian Longitudinal Study on Male Health. BMC Public Health 2016, 16, 1049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xanthopoulou, D.; Bakker, A.B.; Demerouti, E.; Schaufeli, W.B. The role of personal resources in the job demands-resources model. Int. J. Stress Manag. 2007, 14, 121–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wrzesniewski, A.; LoBuglio, N.; Dutton, J.E.; Berg, J.M. Job crafting and cultivating positive meaning and identity in work. In Advances in Positive Organizational Psychology; Bakker, A.B., Ed.; Emerald Group Publishing Limited: Leeds, UK, 2013; Volume 1, pp. 281–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Op den Kamp, E.M.; Bakker, A.B.; Tims, M.; Demerouti, E. Proactive vitality management and creative work performance: The role of self-insight and social support. J. Creat. Behav. 2020, 54, 323–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meunier, S.; Roberge, C.; Coulombe, S.; Houle, J. Feeling better at work! Mental health self-management strategies for workers with depressive and anxiety symptoms. J. Affect. Disord. 2019, 254, 7–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberge, C.; Meunier, S.; Cleary, J. In action at work! Mental health self-management strategies for employees experiencing anxiety or depressive symptoms. Can. J. Behav. Sci. Rev. Can. Sci. Comport. 2024, 56, 10–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barlow, J.; Wright, C.; Sheasby, J.; Turner, A.; Hainsworth, J. Self-management approaches for people with chronic conditions: A review. Patient Educ. Couns. 2002, 48, 177–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorig, K.R.; Holman, H.R. Self-management education: History, definition, outcomes, and mechanisms. Ann. Behav. Med. 2003, 26, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deegan, P.E. Recovery and empowerment for people with psychiatric disabilities. Soc. Work Health Care 1997, 25, 11–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slade, M. Personal Recovery and Mental Illness: A Guide for Mental Health Professionals, 1st ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salge, C.; Glackin, C.; Polani, D. Empowerment—An Introduction. In Guided Self-Organization: Inception; Prokopenko, M., Ed.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2014; Volume 9, pp. 67–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorig, K.R.; Mazonson, P.D.; Holman, H.R. Evidence suggesting that health education for self-management in patients with chronic arthritis has sustained health benefits while reducing health care costs. Arthritis Rheum. 1993, 36, 439–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lorig, K.; Ritter, P.L.; Villa, F.J.; Armas, J. Community-based peer-led diabetes self-management. Diabetes Educ. 2009, 35, 641–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lean, M.; Fornells-Ambrojo, M.; Milton, A.; Lloyd-Evans, B.; Harrison-Stewart, B.; Yesufu-Udechuku, A.; Kendall, T.; Johnson, S. Self-management interventions for people with severe mental illness: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Br. J. Psychiatry J. Ment. Sci. 2019, 214, 260–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorig, K.; Laurent, D.D.; Plant, K.; Krishnan, E.; Ritter, P.L. The components of action planning and their associations with behavior and health outcomes. Chronic Illn. 2014, 10, 50–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, B.; Gu, Y. Effect of self-management training on adherence to medications among community residents with chronic schizophrenia: A singleblind randomized controlled trial in Shanghai, China. Shanghai Arch. Psychiatry 2014, 26, 332–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zoun, M.H.H.; Koekkoek, B.; Sinnema, H.; Van Der Feltz-Cornelis, C.M.; Van Balkom, A.J.L.M.; Schene, A.H.; Smit, F.; Spijker, J. Effectiveness of a self-management training for patients with chronic and treatment resistant anxiety or depressive disorders on quality of life, symptoms, and empowerment: Results of a randomized controlled trial. BMC Psychiatry 2019, 19, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkinson, A.; Whitehead, L. Evolution of the concept of self-care and implications for nurses: A literature review. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2009, 46, 1143–1147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villaggi, B.; Provencher, H.; Coulombe, S.; Meunier, S.; Radziszewski, S.; Hudon, C.; Roberge, P.; Provencher, M.D.; Houle, J. Self-management strategies in recovery from mood and anxiety disorders. Glob. Qual. Nurs. Res. 2015, 2, 2333393615606092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berkman, N.D.; Davis, T.C.; McCormack, L. Health literacy: What is it? J. Health Commun. 2010, 15 (Suppl. S2), 9–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barello, S.; Graffigna, G. Patient engagement in healthcare: Pathways for effective medical decision making. Neuropsychol. Trends 2015, 17, 53–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, J.A.; Copeland, M.E.; Jonikas, J.A.; Hamilton, M.M.; Razzano, L.A.; Grey, D.D.; Floyd, C.B.; Hudson, W.B.; Macfarlane, R.T.; Carter, T.M. Results of a randomized controlled trial of mental illness self-management using Wellness Recovery Action Planning. Schizophr. Bull. 2012, 38, 881–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Druss, B.G.; Zhao, L.; von Esenwein, S.A.; Bona, J.R.; Fricks, L.; Jenkins-Tucker, S.; Sterling, E.; DiClemente, R.; Lorig, K. The health and recovery peer (HARP) program: A peer-led intervention to improve medical self-management for persons with serious mental illness. Schizophr. Res. 2010, 118, 264–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Druss, B.G.; Singh, M.; von Esenwein, S.A.; Glick, G.E.; Tapscott, S.; Tucker, S.J.; Lally, C.A.; Sterling, E.W. Peer-led self-management of general medical conditions for patients with serious mental illnesses: A randomized trial. Psychiatr. Serv. 2018, 69, 529–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goldberg, R.W.; Dickerson, F.; Lucksted, A.; Brown, C.H.; Weber, E.; Tenhula, W.N.; Kreyenbuhl, J.; Dixon, L.B. Living well: An intervention to improve self-management of medical illness for individuals with serious mental illness. Psychiatr. Serv. 2013, 64, 51–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muralidharan, A.; Brown, C.H.; Peer, J.E.; Klingaman, E.A.; Hack, S.M.; Li, L.; Walsh, M.B.; Goldberg, R.W. Living well: An intervention to improve medical illness self-management among individuals with serious mental illness. Psychiatr. Serv. 2019, 70, 19–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schopp, L.H.; Clark, M.J.; Lamberson, W.R.; Uhr, D.J.; Minor, M.A. A randomized controlled trial to evaluate outcomes of a workplace self-management intervention and an intensive monitoring intervention. Health Educ. Res. 2017, 32, 219–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberge, C.; Cleary, J.; Coulombe, S.; Corbière, M.; Meunier, S. Évaluation des effets de l’atelier “Vivre avec un Meilleur équilibre au travail”; Université du Québec à Montréal: Montreal, QC, Canada, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Huff, S.W.; Rapp, C.A.; Campbell, S.R. “Every day is not always Jell-O”: A qualitative study of factors affecting job tenure. Psychiatr. Rehabil. J. 2008, 31, 211–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arneson, H.; Ekberg, K. Evaluation of empowerment processes in a workplace health promotion intervention based on learning in Sweden. Health Promot. Int. 2005, 20, 351–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hemming, S.; McDermott, H.; Munir, F.; Burton, K. Employer perspectives concerning the self-management support needs of workers with long-term health conditions. Int. J. Workplace Health Manag. 2021, 14, 440–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colman, D.E.; Echon, R.; Lemay, M.S.; McDonald, J.; Smith, K.R.; Spencer, J.; Swift, J.K. The efficacy of self-care for graduate students in professional psychology: A meta-analysis. Train. Educ. Prof. Psychol. 2016, 10, 188–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barlow, J. Self-Care. In International Encyclopedia of Rehabilitation; Stone, J.H., Blouin, M., Eds.; Center for International Rehabilitation Research Information and Exchange (CIRRIE): Buffalo, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Riegel, B.; Dunbar, S.B.; Fitzsimons, D.; Freedland, K.E.; Lee, C.S.; Middleton, S.; Stromberg, A.; Vellone, E.; Webber, D.E.; Jaarsma, T. Self-care research: Where are we now? Where are we going? Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2021, 116, 103402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gómez-Borges, A.; Zuberbühler, M.J.P.; Martínez, I.M.; Salanova, M. Self-care at work matters: How job and personal resources mediate between self-care and psychological well-being. Rev. Psicol. Trab. Las Organ. 2022, 38, 231–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, X.; Topps, A.K.; Suzuki, R. A systematic review of self-care measures for professionals and trainees. Train. Educ. Prof. Psychol. 2021, 15, 126–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rupert, P.A.; Dorociak, K.E. Self-care, stress, and well-being among practicing psychologists. Prof. Psychol. Res. Pract. 2019, 50, 343–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.-H.; Joo, M.-H. The moderating effects of self-care on the relationships between perceived stress, job burnout and retention intention in clinical nurses. Healthcare 2023, 11, 1870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coulombe, S.; De la Fontaine, M.-F.; Gauthier, C.-A. Portrait 2022 de la Santé Mentale des Travailleuses et des Travailleurs de PME au Canada; Chaire de Recherche Relief en Santé Mentale, Autogestion et Travail, Université Laval: Quebec City, QC, Canada, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Villeneuve, M.; Coulombe, S.; Missud, A. Portrait of the Mental Health of SME Workers in Canada 2023; Chaire de Recherche Relief en Santé Mentale, Autogestion et Travail, Université Laval: Quebec City, QC, Canada, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Keyes, C.L.M. The Mental Health Continuum: From Languishing to Flourishing in Life. J. Health Soc. Behav. 2002, 43, 207–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavakol, M.; Dennick, R. Making sense of Cronbach’s alpha. Int. J. Med. Educ. 2011, 2, 53–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Streiner, D.L.; Kottner, J. Recommendations for reporting the results of studies of instrument and scale development and testing. J. Adv. Nurs. 2014, 70, 1970–1979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pacheco, T.; Coulombe, S.; Meunier, S. When work conflicts with personal projects: The association of work-life conflict with worker wellbeing and the mediating role of mindfulness. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 539582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Briggs, S.R.; Cheek, J.M. The role of factor analysis in the development and evaluation of personality scales. J. Pers. 1986, 54, 106–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biron, C.; St-Hilaire, F.; Baril-Gingras, G.; Paradis, M.-E.; Chabot, S.; Lefebvre, R.; Ivers, H.; Vézina, M.; Fournier, P.-S.; Gilbert-Ouimet, M.; et al. Conditions Facilitant l’Appropriation de Démarches Préventives en Santé Psychologique au Travail par les Gestionnaires; IRSST: Montreal, QC, Canada, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Lippel, K.; Vézina, M.; Bourbonnais, R.; Funes, A. Workplace psychological harassment: Gendered exposures and implications for policy. Int. J. Law Psychiatry 2016, 46, 74–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haines, V.Y., III; Ricardeau Registre, J.F.; Guerrero, S. Challenging (-hindering) employment and employee health. Rel. Ind./Ind. Rel. 2022, 77, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilbert, M.-H.; Malo, M. Psychological Health at Work: A Measurement Scale Validation. In Proceedings of the 18th European Association of Work and Organizational Psychology Congress, Dublin, Ireland, 17–20 May 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert, M.-H.; Dagenais-Desmarais, V.; Savoie, A. Validation d’une mesure de santé psychologique au travail. Eur. Rev. Appl. Psychol. 2011, 61, 195–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sassi, N.; Neveu, J.-P. Traduction et validation d’une nouvelle mesure d’épuisement professionnel: Le shirom-melamed burnout measure. [Translation and validation of a new measurement of professional exhaustion: The Shirom-Melamed Burnout Measure.]. Can. J. Behav. Sci. Rev. Can. Sci. Comport. 2010, 42, 177–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shirom, A.; Melamed, S. A comparison of the construct validity of two burnout measures in two groups of professionals. Int. J. Stress Manag. 2006, 13, 176–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golz, C.; Gerlach, M.; Kilcher, G.; Peter, K.A. Cultural adaptation and validation of the health and work performance questionnaire in german. J. Occup. Environ. Med. 2022, 64, e845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harvard University. Traduction Française du Health and Work Performance Questionnaire. Available online: https://www.hcp.med.harvard.edu/hpq/ftpdir/French_HPQ_ShortForm.pdf (accessed on 28 June 2025).

- Kessler, R.C.; Barber, C.; Beck, A.; Berglund, P.; Cleary, P.D.; McKenas, D.; Pronk, N.; Simon, G.; Stang, P.; Ustun, T.B.; et al. The World Health Organization Health and Work Performance Questionnaire (HPQ). J. Occup. Environ. Med. 2003, 45, 156–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kessler, R.C.; Ames, M.; Hymel, P.A.; Loeppke, R.; McKenas, D.K.; Richling, D.E.; Stang, P.E.; Ustun, T.B. Using the World Health Organization Health and Work Performance Questionnaire (HPQ) to evaluate the indirect workplace costs of illness. J. Occup. Environ. Med. 2004, 46 (Suppl. S6), S23–S37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kroenke, K.; Spitzer, R.L.; Williams, J.B.W.; Löwe, B. An ultra-brief screening scale for anxiety and depression: The PHQ-4. Psychosomatics 2009, 50, 613–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villieux, A.; Sovet, L.; Jung, S.-C.; Guilbert, L. Psychological flourishing: Validation of the French version of the Flourishing Scale and exploration of its relationships with personality traits. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2016, 88, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diener, E.; Wirtz, D.; Biswas-Diener, R.; Tov, W.; Kim-Prieto, C.; Choi, D.; Oishi, S. New measures of well-being. In Assessing Well-Being: The Collected Works of Ed Diener; Diener, E., Ed.; Social Indicators Research Series; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2009; pp. 247–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IBM Corp. IBM SPSS Statistics for Macintosh, Version 28.0; IBM Corp.: Armonk, NY, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Muthén, L.K.; Muthén, B.O. Mplus User’s Guide: Statistical Analysis with Latent Variables, User’s Guide, 8th ed.; Muthén & Muthén: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Coulombe, S.; Pacheco, T.; Cox, E.; Khalil, C.; Doucerain, M.M.; Auger, E.; Meunier, S. Risk and resilience factors during the COVID-19 pandemic: A snapshot of the experiences of Canadian workers early on in the crisis. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 580702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Wang, X. Structural Equation Modeling: Applications Using Mplus; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Hooper, D.; Coughlan, J.; Mullen, M. Structural equation modelling: Guidelines for determining model fit. Electron. J. Bus. Res. Methods 2008, 6, 53–60. [Google Scholar]

- Enders, C.K. Applied Missing Data Analysis; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Sardeshmukh, S.R.; Vandenberg, R.J. Integrating moderation and mediation: A structural equation modeling approach. Organ. Res. Methods 2017, 20, 721–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, G.W.; Cooper-Thomas, H.D.; Lau, R.S.; Wang, L.C. Reporting reliability, convergent and discriminant validity with structural equation modeling: A review and best-practice recommendations. Asia Pac. J. Manag. 2024, 41, 745–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zait, A.; Bertea, P. Methods for testing discriminant validity. Manag. Mark. 2011, 9, 217–224. [Google Scholar]

- Henseler, J.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2015, 43, 115–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spector, P.E.; Brannick, M.T. Common method variance or measurement bias? The problem and possible solutions. In The Sage Handbook of Organizational Research Methods; Buchanan, D.A., Bryman, A., Eds.; Sage Publications Ltd.: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2009; pp. 346–362. [Google Scholar]

- Ramos, C.; Costa, P.A.; Rudnicki, T.; Marôco, A.L.; Leal, I.; Guimarães, R.; Fougo, J.L.; Tedeschi, R.G. The effectiveness of a group intervention to facilitate posttraumatic growth among women with breast cancer. Psychooncology 2018, 27, 258–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moss, J. Rethinking burnout: When self care is not the cure. Am. J. Health Promot. 2020, 34, 565–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kickul, J.; Posig, M. Surpervisory emotional support and burnout: An explanation of reverse buffering effects. J. Manag. Issues 2001, 13, 328–344. [Google Scholar]

- Nahum-Shani, I.; Henderson, M.M.; Lim, S.; Vinokur, A.D. Supervisor support: Does supervisor support buffer or exacerbate the adverse effects of supervisor undermining? J. Appl. Psychol. 2014, 99, 484–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kossek, E.E.; Valcour, M.; Lirio, P. The sustainable workforce: Organizational strategies for promoting work–life balance and wellbeing. In Wellbeing; Cooper, C.L., Ed.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2014; pp. 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barlow, J.H.; Ellard, D.; Hainsworth, J.; Jones, F.; Fisher, A. A review of self-management interventions for panic disorders, phobias and obsessive-compulsive disorders. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 2005, 111, 272–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giga, S.I.; Cooper, C.L.; Faragher, B. The development of a framework for a comprehensive approach to stress management interventions at work. Int. J. Stress Manag. 2003, 10, 280–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, A.; Bevans, M.; Brooks, A.T.; Gibbons, S.; Wallen, G.R. Nurses and health-promoting behaviors: Knowledge may not translate into self-care. AORN J. 2017, 105, 267–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reavley, N.J.; Morgan, A.J.; Jorm, A.F. Disclosure of mental health problems: Findings from an Australian national survey. Epidemiol. Psychiatr. Sci. 2018, 27, 346–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toth, K.E.; Yvon, F.; Villotti, P.; Lecomte, T.; Lachance, J.-P.; Kirsh, B.; Stuart, H.; Berbiche, D.; Corbière, M. Disclosure dilemmas: How people with a mental health condition perceive and manage disclosure at work. Disabil. Rehabil. 2022, 44, 7791–7801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szeto, A.C.H.; Dobson, K.S. Reducing the stigma of mental disorders at work: A review of current workplace anti-stigma intervention programs. Appl. Prev. Psychol. 2010, 14, 41–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberge, C.; Meunier, S. Development and initial validation of a questionnaire measuring self-management strategies that promote psychological health at work. J. Occup. Rehabil. 2023, 34, 238–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haar, J.M.; Russo, M.; Suñe, A.; Ollier-Malaterre, A. Outcomes of work–life balance on job satisfaction, life satisfaction and mental health: A study across seven cultures. J. Vocat. Behav. 2014, 85, 361–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joyce, S.; Modini, M.; Christensen, H.; Mykletun, A.; Bryant, R.; Mitchell, P.B.; Harvey, S.B. Workplace interventions for common mental disorders: A systematic meta-review. Psychol. Med. 2016, 46, 683–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LaMontagne, A.D.; Martin, A.; Page, K.M.; Reavley, N.J.; Noblet, A.J.; Milner, A.J.; Keegel, T.; Smith, P.M. Workplace mental health: Developing an integrated intervention approach. BMC Psychiatry 2014, 14, 131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wise, E.H.; Hersh, M.A.; Gibson, C.M. Ethics, self-care and well-being for psychologists: Reenvisioning the stress-distress continuum. Prof. Psychol. Res. Pract. 2012, 43, 487–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | Frequency (%) or Mean (SD) | |

|---|---|---|

| Participants Who Answered SM Questions (n = 400) | Full Sample (N = 896) | |

| AGE (YEARS) | 43.75 (11.03) | 43.20 (11.92) |

| GENDER | ||

| Men | 165 (41.30) | 336 (37.50) |

| Women | 234 (58.50) | 556 (62.10) |

| Non-binary | 0 (0.00) | 1 (0.10) |

| Missing/Prefer not to say (%) | 1 (0.30) | 3 (0.30) |

| MARITAL STATUS | ||

| Married | 112 (28.00) | 250 (27.90) |

| Common law | 151 (37.80) | 336 (37.50) |

| Never married | 108 (27.00) | 239 (26.70) |

| Separated | 6 (1.50) | 17 (1.90) |

| Divorced | 20 (5.00) | 39 (4.40) |

| Widowed | 1 (0.30) | 12 (1.30) |

| Other (e.g., Fiancé, Couple living separately) | 2 (0.50) | 3 (0.30) |

| IDENTIFIED AS A PERSON OF COLOR | ||

| Yes | 16 (4.00) | 38 (4.20) |

| No | 382 (95.50) | 854 (95.30) |

| Prefer not to say (%) | 2 (0.50) | 4 (0.40) |

| BORN IN CANADA | ||

| Yes | 364 (91.00) | 816 (91.10) |

| No | 36 (9.00) | 80 (8.90) |

| PROVINCE OF RESIDENCE a | ||

| Alberta | 1 (0.30) | 1 (0.10) |

| New Brunswick | 0 (0.00) | 1 (0.10) |

| Ontario | 3 (0.80) | 5 (0.60) |

| Prince Edward Island | 1 (0.30) | 1 (0.10) |

| Quebec | 395 (98.80) | 887 (99.00) |

| Saskatchewan | 0 (0.00) | 1 (0.10) |

| HAS AT LEAST ONE DISABILITY | ||

| Yes | 20 (5.00) | 55 (6.10) |

| No | 380 (95.00) | 837 (93.40) |

| Missing/Prefer not to say (%) | 0 (0.00) | 4 (0.40) |

| EMPLOYMENT STATUS a | ||

| Employed/self-employed full-time (30+ hours/week) | 326 (81.50) | 693 (77.30) |

| Employee or self-employed (20–29 h/week) | 34 (8.50) | 83 (9.30) |

| Employee or self-employed (<20 h/week) | 27 (6.80) | 70 (7.80) |

| On leave for physical or mental health problems | 9 (2.30) | 2 3(2.60) |

| Retired | 1 (0.30) | 6 (0.70) |

| Full-time student | 8 (2.00) | 21 (2.30) |

| Part-time student | 15 (3.80) | 20 (2.20) |

| Unemployed and looking for work | 5 (1.30) | 18 (2.00) |

| Unemployed and not looking for work | 2 (0.50) | 6 (0.70) |

| Receiving employment insurance benefits | 4 (1.00) | 12 (1.30) |

| Receiving disability benefits | 2 (0.50) | 4 (0.40) |

| Social assistance recipient | 0 (0.00) | 1 (0.10) |

| Other (e.g., Maternity leave, COVID-19-related layoff) | 2(0.50) | 11(1.20) |

| WORK INDUSTRY a | ||

| Retail | 33 (8.30) | 67 (7.50) |

| Other services excluding public administration (e.g., repair, maintenance) | 23 (5.80) | 57 (6.40) |

| Professional, scientific, and technical services | 85 (21.30) | 188 (21.00) |

| Arts, entertainment, and recreation | 22 (5.50) | 30 (3.30) |

| Finance and insurance | 27 (6.80) | 58 (6.50) |

| Health care and social assistance | 49 (12.30) | 129 (14.40) |

| Construction | 12 (3.00) | 25 (2.80) |

| Accommodation and food services | 5 (1.30) | 9 (1.00) |

| Education | 41 (10.30) | 81 (9.00) |

| Wholesale trade | 3 (0.80) | 15 (1.70) |

| Manufacturing | 19 (4.80) | 35 (3.90) |

| Information and cultural industries | 6 (1.50) | 14 (1.60) |

| Transportation and warehousing | 5 (1.30) | 11 (1.20) |

| Agriculture, forestry, fishing, and hunting | 8 (2.00) | 20 (2.20) |

| Company/Enterprise management | 5 (1.30) | 7 (0.80) |

| Real estate and rental and leasing services | 4 (1.00) | 9 (1.00) |

| Administrative and support, waste management, and remediation services | 14 (3.50) | 28 (3.10) |

| Public administration | 44 (11.00) | 84 (9.40) |

| Mining and oil and gas extraction | 1 (0.30) | 3 (0.30) |

| Utilities (electricity, gas, and water services) | 6 (1.50) | 12 (1.30) |

| Other | 1 (0.30) | 9 (0.90) |

| Missing (%) | 20 (5.00) | 71 (7.90) |

| Construct | N | M | SD | S | K | 1. | 2. | 3. | 4. | 5. | 6. | 7. | 8. | 9. | 10. | 11. | 12. | 13. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Psychological demands | 743 | 2.28 | 0.90 | 0.35 | −0.59 | - | ||||||||||||

| 2. Competency-related autonomy | 792 | 2.90 | 0.64 | −0.58 | 0.33 | 0.07 * | - | |||||||||||

| 3. Decisional authority | 795 | 3.17 | 0.69 | −0.73 | 0.32 | −0.08 * | 0.29 *** | - | ||||||||||

| 4. Coworkers’ support | 690 | 3.32 | 0.54 | −0.72 | 0.27 | −0.13 *** | 0.27 *** | 0.31 *** | - | |||||||||

| 5. Supervisors’ support | 662 | 3.32 | 0.64 | −1.20 | 1.56 | −0.21 *** | 0.20 *** | 0.35 *** | 0.56 *** | - | ||||||||

| 6. Recognition | 757 | 3.00 | 0.54 | −0.39 | 0.06 | −0.26 *** | 0.20 *** | 0.37 *** | 0.56 *** | 0.59 *** | - | |||||||

| 7. Self-management at work | 400 | 3.30 | 0.67 | −0.39 | 1.07 | −0.10 t | 0.15 ** | 0.21 *** | 0.30 *** | 0.27 *** | 0.31 *** | - | ||||||

| 8. Positive well-being at work | 805 | 5.29 | 1.04 | −0.68 | 0.83 | −0.24 *** | 0.23 *** | 0.34 *** | 0.43 *** | 0.36 *** | 0.50 *** | 0.38 *** | - | |||||

| 9. Burnout | 803 | 2.98 | 1.20 | 0.26 | −0.38 | 0.38 *** | −0.06 | −0.21 *** | −0.30 *** | −0.26 *** | −0.38 *** | −0.16 ** | −0.66 *** | - | ||||

| 10. Anxiety | 896 | 1.31 | 1.61 | 1.33 | 1.20 | 0.19 *** | −0.01 | −0.07 * | −0.10 ** | −0.09 * | −0.19 *** | −0.10 t | −0.45 *** | 0.55 *** | - | |||

| 11. Depression | 896 | 1.17 | 1.51 | 1.53 | 2.02 | 0.20 *** | −0.05 | −0.09 ** | −0.15 *** | −0.13 *** | −0.23 *** | −0.15 ** | −0.57 *** | 0.63 *** | 0.71 *** | - | ||

| 12. Flourishing | 896 | 5.58 | 0.94 | −0.60 | 0.21 | −0.20 *** | 0.23 *** | 0.26 *** | 0.35 *** | 0.32 *** | 0.46 *** | 0.28 *** | 0.71 *** | −0.52 *** | −0.42 *** | −0.55 *** | - | |

| 13. Work performance | 801 | 7.92 | 1.44 | −1.01 | 1.97 | −0.16 *** | 0.09 ** | 0.23 *** | 0.29 *** | 0.28 *** | 0.35 *** | 0.24 *** | 0.52 *** | −0.45 *** | −0.27 *** | −0.37 *** | 0.46 *** | - |

| DV: Positive Well-Being at Work | DV: Burnout | DV: Anxiety | DV: Depression | DV: Flourishing | DV: Work Performance | |||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | β | 95% CI [LL, UL] | DR2 | B | β | 95% CI [LL, UL] | DR2 | B | β | 95% CI [LL, UL] | DR2 | B | β | 95% CI [LL, UL] | DR2 | B | β | 95% CI [LL, UL] | DR2 | B | β | 95% CI [LL, UL] | DR2 | |

| IV: Psychological demands | −0.13 ** | −0.12 | −0.22, −0.05 | 0.38 *** | 0.29 | 0.27, 0.48 | 0.12 *** | 0.16 | 0.06, 0.19 | 0.12 *** | 0.17 | 0.06, 0.18 | −0.15 ** | −0.13 | −0.24, −0.05 | −0.11 t | −0.08 | −0.23, 0.01 | ||||||

| MOD: SM at work | 0.68 *** | 0.25 | 0.27, 0.34 | −0.21 | −0.07 | −0.63, 0.22 | −0.21 | −0.11 | −0.46, 0.05 | −0.17 | −0.10 | −0.41, 0.07 | 0.38 * | 0.14 | 0.03, 0.73 | 0.70 * | 0.20 | 0.14, 1.26 | ||||||

| Interaction term | 0.35 ** | 0.13 | 0.12, 0.57 | 0.016 | 0.02 | 0.01 | −0.34, 0.38 | 0.007 | −0.20 * | −0.11 | −0.39, −0.01 | 0.015 | −0.24 * | −0.14 | −0.44, −0.04 | 0.020 | 0.18 | 0.07 | −0.06, 0.42 | 0.003 | 0.55 ** | 0.16 | 0.18, 0.93 | 0.024 |

| IV: Competency-related autonomy | 0.28 | 0.12 | −0.06, 0.61 | 0.07 | 0.03 | −0.30, 0.44 | −0.03 | −0.02 | −0.29, 0.22 | −0.08 | −0.06 | −0.33, 0.16 | 0.54 ** | 0.23 | 0.15, 0.93 | 0.07 | 0.02 | −0.40, 0.53 | ||||||

| MOD: SM at work | 0.62 ** | 0.23 | 0.19, 1.04 | −0.23 | −0.07 | −0.64, 0.19 | −0.17 | −0.09 | −0.42, 0.08 | −0.05 | −0.03 | −0.28, 0.19 | 0.43 * | 0.15 | 0.05, 0.80 | 0.57 t | 0.16 | −0.02, 1.16 | ||||||

| Interaction term | −0.70 * | −0.12 | −1.34, −0.05 | 0.010 | −0.58 | −0.09 | −1.76, 0.60 | 0.018 | −0.02 | −0.01 | −0.49, 0.45 | 0.003 | 0.33 | 0.09 | −0.27, 0.93 | 0.002 | −0.62 t | −0.11 | −1.34, 0.10 | 0.016 | −0.80 | −0.11 | −2.10, 0.49 | 0.001 |

| IV: Decisional authority | 0.18 | 0.08 | −0.13, 0.50 | −0.14 | −0.06 | −0.53, 0.25 | −0.04 | −0.03 | −0.33, 0.25 | 0.03 | 0.02 | −0.23, 0.29 | −0.01 | −0.01 | −0.36, 0.34 | 0.43 t | 0.15 | −0.07, 0.94 | ||||||

| MOD: SM at work | 0.65 *** | 0.25 | 0.27, 1.04 | −0.19 | −0.06 | −0.59, 0.21 | −0.16 | −0.09 | −0.40, 0.08 | −0.09 | −0.05 | −0.31, 0.14 | 0.42 ** | 0.15 | 0.09, 0.75 | 0.64 * | 0.18 | 0.04, 1.25 | ||||||

| Interaction term | −0.90 ** | −0.17 | −1.49, −0.31 | 0.016 | −0.18 | −0.03 | −1.36, 1.01 | 0.009 | 0.26 | 0.07 | −0.28, 0.80 | 0.001 | 0.45 | 0.13 | −0.26, 1.15 | 0.001 | −0.57t | −0.11 | −1.15, 0.02 | 0.000 | −0.96 | −0.14 | −2.27, 0.35 | 0.015 |

| IV: Coworkers’ support | 0.42 | 0.16 | −0.39, 1.24 | −0.11 | −0.04 | −1.03, 0.80 | −0.03 | −0.02 | −0.66, 0.60 | −0.04 | −0.03 | −0.66, 0.57 | 0.04 | 0.01 | −0.76, 0.83 | 0.81 | 0.24 | −0.35, 1.97 | ||||||

| MOD: SM at work | 0.75 *** | 0.27 | 0.30, 1.21 | −0.22 | −0.07 | −0.66, 0.23 | −0.18 | −0.09 | −0.45, 0.09 | −0.15 | −0.08 | −0.41, 0.11 | 0.47 * | 0.16 | 0.09, 0.84 | 0.73 * | 0.19 | 0.07, 1.39 | ||||||

| Interaction term | −0.88 ** | −0.13 | −1.49, −0.27 | 0.018 | −0.41 | −0.05 | −1.62, 0.80 | 0.015 | 0.33 | 0.07 | −0.26, 0.91 | 0.000 | 0.45 | 0.10 | −0.24, 1.14 | 0.001 | −0.54 | −0.08 | −1.23, 0.16 | 0.001 | −0.57 | −0.06 | −1.71, 0.56 | 0.012 |

| IV: Supervisors’ support | −0.27 t | −0.16 | −0.57, 0.03 | 0.41 * | 0.21 | 0.05, 0.77 | 0.05 | 0.04 | −0.19, 0.29 | 0.15 | 0.14 | −0.07, 0.37 | −0.09 | −0.05 | −0.38, 0.20 | −0.09 | −0.04 | −0.51, 0.32 | ||||||

| MOD: SM at work | 0.69 ** | 0.25 | 0.25, 1.12 | −0.19 | −0.06 | −0.62, 0.24 | −0.17 | −0.09 | −0.42, 0.09 | −0.10 | −0.05 | −0.34, 0.14 | 0.43 * | 0.15 | 0.06, 0.80 | 0.65 * | 0.18 | 0.03, 1.27 | ||||||

| Interaction term | −0.51 *** | −0.12 | −0.81, −0.21 | −0.001 | −0.13 | −0.03 | −0.86, 0.59 | 0.006 | 0.24 | 0.08 | −0.06, 0.54 | −0.001 | 0.31 t | 0.11 | −0.03, 0.64 | −0.005 | −0.26 | −0.06 | −0.64, 0.12 | −0.003 | −0.30 | −0.05 | −0.87, 0.28 | −0.003 |

| IV: Recognition | 0.94 *** | 0.52 | 0.37, 1.51 | −1.15 *** | −0.53 | −1.81, −0.49 | −0.35 | −0.28 | −0.81, 0.11 | −0.50 ** | −0.43 | −0.90, −0.10 | 0.88 ** | 0.47 | 0.27, 1.50 | 0.47 | 0.19 | −0.24, 1.17 | ||||||

| MOD: SM at work | 0.74 *** | 0.28 | 0.32, 1.16 | −0.23 | −0.07 | −0.66, 0.20 | −0.20 | −0.10 | −0.45, 0.06 | −0.16 | −0.09 | −0.41, 0.08 | 0.46 ** | 0.17 | 0.10, 0.82 | 0.70 * | 0.20 | 0.09, 1.30 | ||||||

| Interaction term | −0.55 *** | −0.12 | −0.86, −0.24 | 0.020 | −0.18 | −0.03 | −0.88, 0.51 | 0.016 | 0.26 | 0.08 | −0.05, 0.56 | 0.008 | 0.31 t | 0.11 | −0.05, 0.66 | 0.009 | −0.30 t | −0.06 | −0.66, 0.06 | 0.005 | −0.39 | −0.07 | −0.97, 0.19 | 0.005 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gauthier, C.-A.; Pacheco, T.; Proteau, É.; Auger, É.; Coulombe, S. Self-Management at Work’s Moderating Effect on the Relations Between Psychosocial Work Factors and Well-Being. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2025, 22, 1070. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22071070

Gauthier C-A, Pacheco T, Proteau É, Auger É, Coulombe S. Self-Management at Work’s Moderating Effect on the Relations Between Psychosocial Work Factors and Well-Being. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2025; 22(7):1070. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22071070

Chicago/Turabian StyleGauthier, Carol-Anne, Tyler Pacheco, Élisabeth Proteau, Émilie Auger, and Simon Coulombe. 2025. "Self-Management at Work’s Moderating Effect on the Relations Between Psychosocial Work Factors and Well-Being" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 22, no. 7: 1070. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22071070

APA StyleGauthier, C.-A., Pacheco, T., Proteau, É., Auger, É., & Coulombe, S. (2025). Self-Management at Work’s Moderating Effect on the Relations Between Psychosocial Work Factors and Well-Being. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 22(7), 1070. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22071070