Exploring Community Co-Creation in Tree Planting and Heat-Related Health Interventions: A Qualitative Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

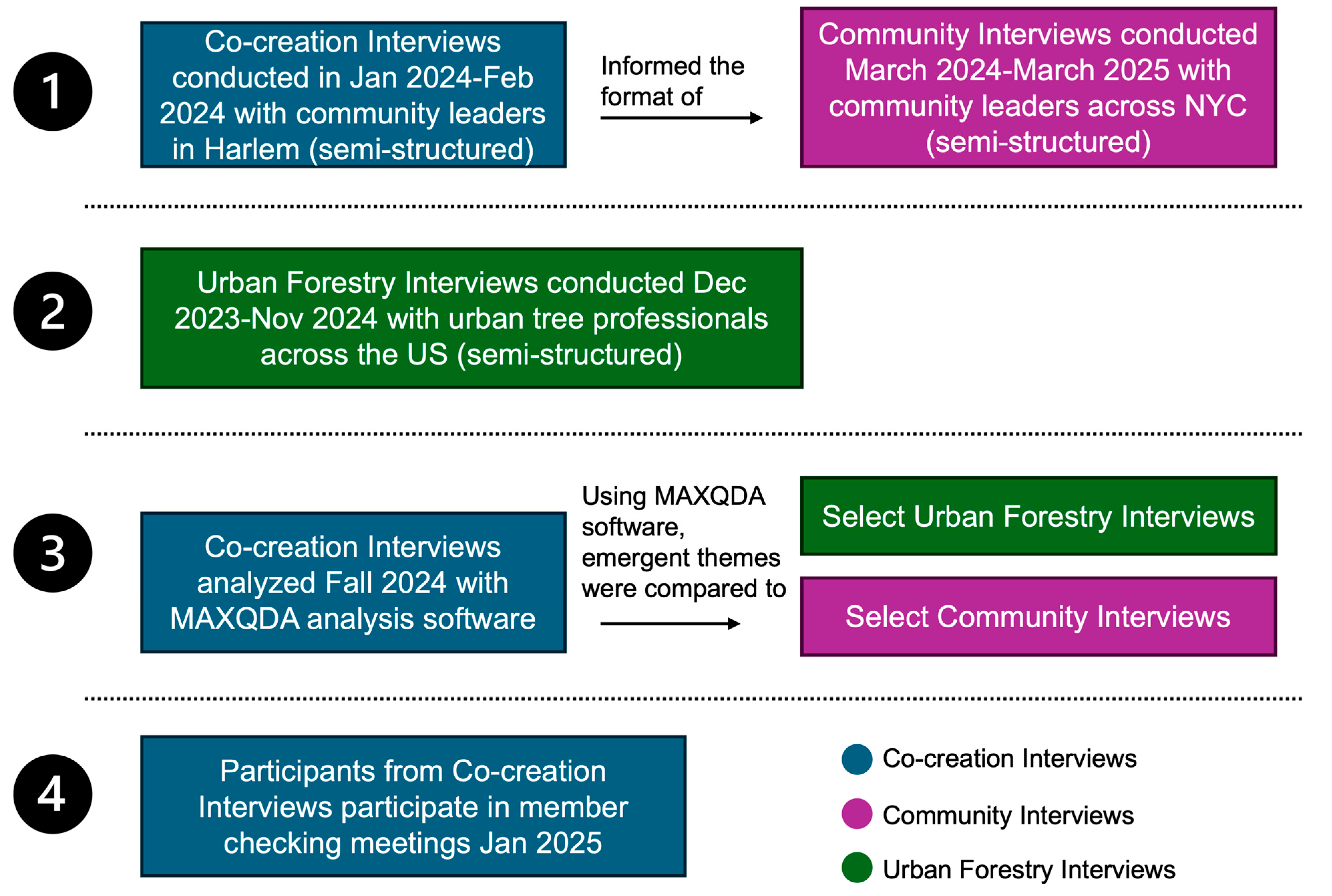

2. Materials and Methods

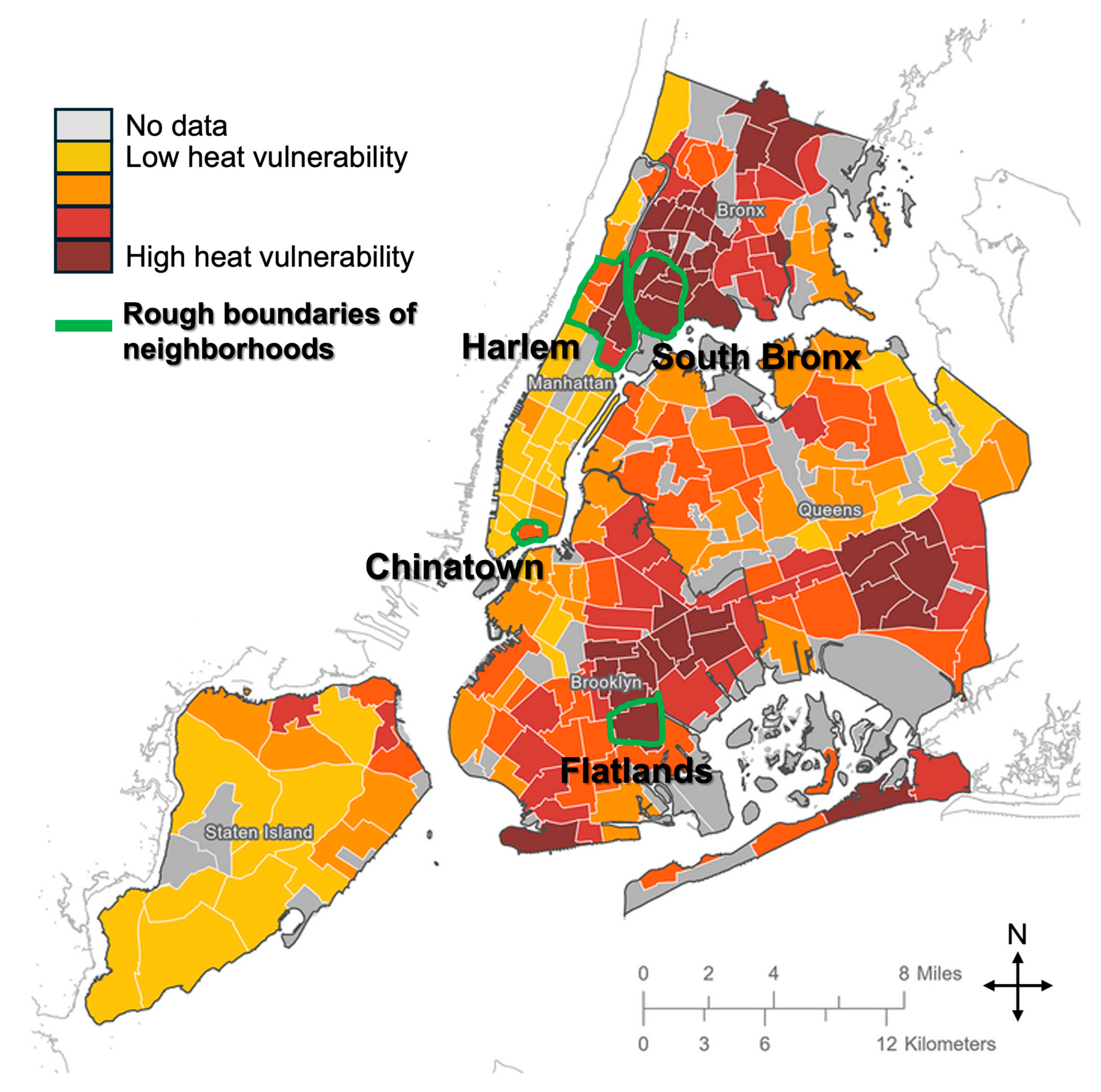

2.1. Overview of Participants and Interviews

2.2. Co-Creation Interviews and Inductive Coding

2.2.1. Co-Creation Interview Process

2.2.2. Inductive Coding Analysis

2.3. Other Interviews and Deductive Coding

2.3.1. Community and Urban Forestry Interviews

2.3.2. Deductive Coding Analysis

2.4. Member Checking and Research Co-Creation

3. Results

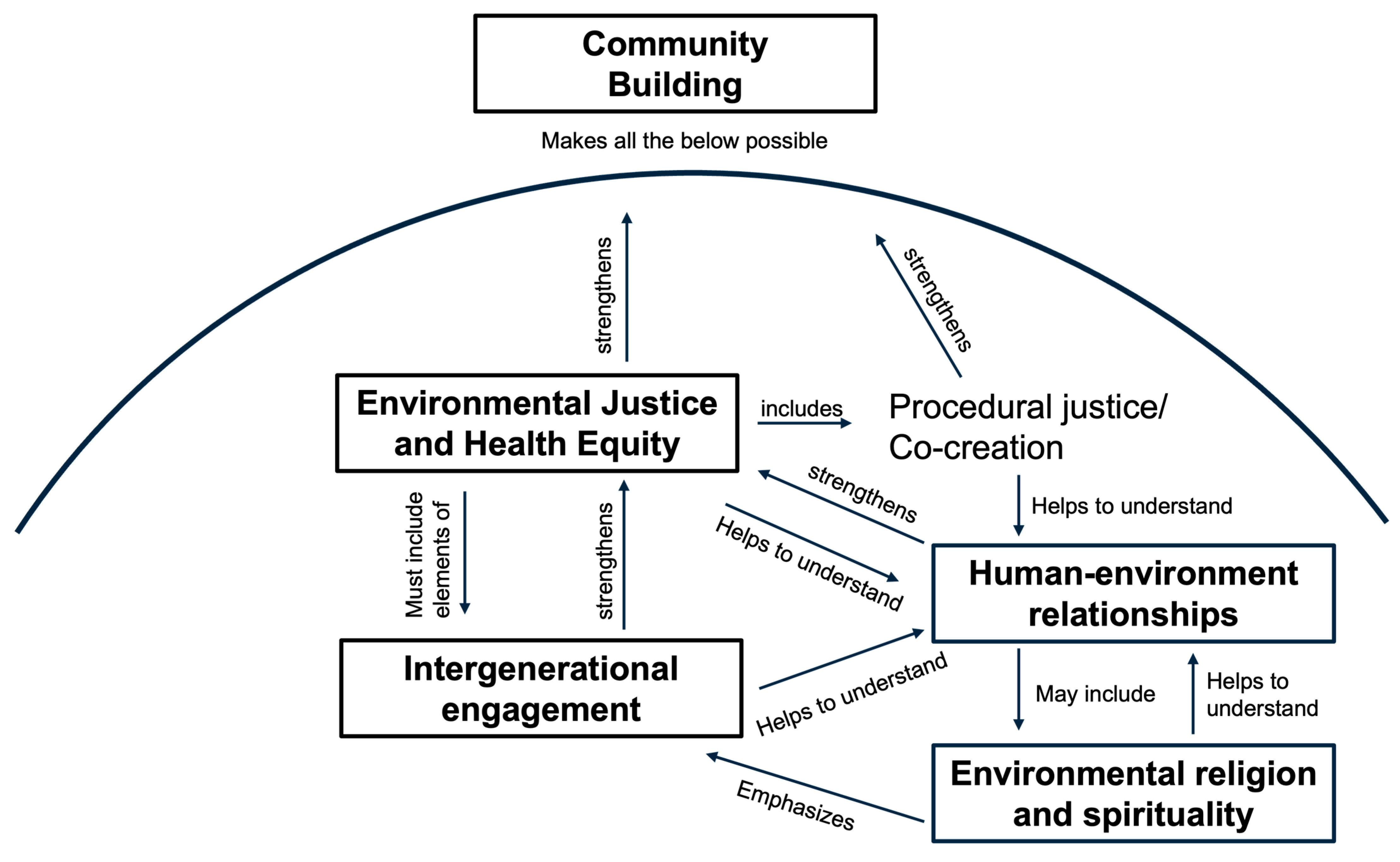

3.1. Inductive Data Analysis

- Environmental justice and health equity are interlinked and at the heart of this research;

- Religious and spiritual communities are important touchpoints in urban greening research;

- Intergenerational engagement ensures intergenerational inclusion;

- Human–environment relationships vary by individual and community;

- Community building makes co-creation and knowledge sharing between communities and researchers possible.

3.1.1. Inductive Analysis: Environmental Justice and Health Equity Are Interlinked and at the Heart of This Research

3.1.2. Inductive Analysis: Religious and Spiritual Communities Are Important Touchpoints in Urban Greening Research

3.1.3. Inductive Analysis: Intergenerational Engagement Ensures Intergenerational Inclusion

3.1.4. Inductive Analysis: Human–Environment Relationships Vary by Individual and Community

3.1.5. Inductive Analysis: Community Building Makes Co-Creation and Knowledge Sharing Between Communities and Researchers Possible

3.2. Deductive Coding Analysis of Other Interviews

3.2.1. Deductive Analysis: Environmental Justice and Health Equity Are Interlinked and at the Heart of This Research

3.2.2. Deductive Analysis: Religious and Spiritual Communities Are Important Touchpoints in Urban Greening Research

3.2.3. Deductive Analysis: Intergenerational Engagement Ensures Intergenerational Inclusion

3.2.4. Deductive Analysis: Human–Environment Relationships Vary by Individual and Community and Community Building Makes Co-Creation and Knowledge Sharing Between Communities and Researchers Possible

3.3. Results of Member Checking and Research Co-Creation

4. Discussion

4.1. Discussion of Emergent Themes

4.2. Comparing Co-Creation Interviews and Other Interviews

4.3. Reflection on the Co-Creation Process

4.4. Limitations and Future Work

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CAB | Community Advisory Board |

| NYC | New York City |

References

- Meehl, G.A.; Tebaldi, C. More Intense, More Frequent, and Longer Lasting Heat Waves in the 21st Century. Science 2004, 305, 994–997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Habeeb, D.; Vargo, J.; Stone, B. Rising heat wave trends in large US cities. Nat. Hazards 2015, 76, 1651–1665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaidyanathan, A.; Gates, A.; Brown, C.; Prezzato, E.; Bernstein, A. Heat-Related Emergency Department Visits -- United States, May-September 2023. Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2024, 73, 324–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vaidyanathan, A.; Malilay, J.; Schramm, P.; Saha, S. Heat-Related Deaths—United States, 2004–2018. MMWR. Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2020, 69, 729–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, Y.; Wu, Y.; Guo, X.; Kou, W.; Zhang, S.; Leung, L.R.; Chen, X.; Lu, J.; Diffenbaugh, N.S.; Horton, D.E.; et al. More Frequent and Persistent Heatwaves Due To Increased Temperature Skewness Projected by a High-Resolution Earth System Model. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2023, 50, e2023GL105840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Service, N.W. Weather Related Fatality and Injury Statistics. Available online: https://www.weather.gov/hazstat/ (accessed on 25 May 2025).

- Sun, S.; Weinberger, K.R.; Spangler, K.R.; Eliot, M.N.; Braun, J.M.; Wellenius, G.A. Ambient temperature and preterm birth: A retrospective study of 32 million US singleton births. Environ. Int. 2019, 126, 7–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marí-Dell’Olmo, M.; Oliveras, L.; Barón-Miras, L.E.; Borrell, C.; Montalvo, T.; Ariza, C.; Ventayol, I.; Mercuriali, L.; Sheehan, M.; Gómez-Gutiérrez, A.; et al. Climate Change and Health in Urban Areas with a Mediterranean Climate: A Conceptual Framework with a Social and Climate Justice Approach. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 12764. Available online: https://www.mdpi.com/1660-4601/19/19/12764 (accessed on 25 May 2025). [CrossRef]

- Taha, H. Urban climates and heat islands: Albedo, evapotranspiration, and anthropogenic heat. Energy Build. 1997, 25, 99–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Lee, X.; Smith, R.B.; Oleson, K. Strong contributions of local background climate to urban heat islands. Nature 2014, 511, 216–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, N.H.; Tan, C.L.; Kolokotsa, D.D.; Takebayashi, H. Greenery as a mitigation and adaptation strategy to urban heat. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 2021, 2, 166–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.; Li, Q. Greenspace, bluespace, and their interactive influence on urban thermal environments. Environ. Res. Lett. 2020, 15, 034041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shadman, S.; Khalid, P.A.; Hanafiah, M.M.; Koyande, A.K.; Islam, A.; Bhuiyan, S.A.; Woon, K.S.; Show, P.-L. The carbon sequestration potential of urban public parks of densely populated cities to improve environmental sustainability. Sustain. Energy Technol. Assess. 2022, 52, 102064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowak, D.J.; Bodine, A.R.; Hoehn, R.E.; Ellis, A.; Hirabayashi, S.; Coville, R.; Auyeung, D.N.; Sonti, N.F.; Hallett, R.A.; Johnson, M.L.; et al. The Urban Forest of New York City. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Northern Research Station, 2018. Available online: https://doi.org/10.2737/NRS-RB-117 (accessed on 25 May 2025).

- Mason, E.; Montalto, F.A. The overlooked role of New York City urban yards in mitigating and adapting to climate change. Local Environ. 2015, 20, 1412–1427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Q.; Lin, J.; Ju, Y.; Li, W.; Liang, L.; Guo, Q. Individual structure mapping over six million trees for New York City USA. Sci. Data 2023, 10, 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pamukcu-Albers, P.; Ugolini, F.; La Rosa, D.; Grădinaru, S.R.; Azevedo, J.C.; Wu, J. Building green infrastructure to enhance urban resilience to climate change and pandemics. Landsc. Ecol. 2021, 36, 665–673. (In English) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The City of New York. To Amend the Administrative Code of the City of New York, in Relation to an Urban Forest Plan. Vol. No. 148, 2023. Available online: https://legistar.council.nyc.gov/LegislationDetail.aspx?ID=6229337&GUID=D9415665-C1D2-42C2-93D5-402340A7B90E (accessed on 25 May 2025).

- Nyelele, C.; Kroll, C.N. The equity of urban forest ecosystem services and benefits in the Bronx, NY. Urban For. Urban Green. 2020, 53, 126723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, A.; Sheriff, G.; Chakraborty, T.; Manya, D. Disproportionate exposure to urban heat island intensity across major US cities. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 2721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Volin, E.; Ellis, A.; Hirabayashi, S.; Maco, S.; Nowak, D.J.; Parent, J.; Fahey, R.T. Assessing macro-scale patterns in urban tree canopy and inequality. Urban For. Urban Green. 2020, 55, 126818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klompmaker, J.O.; Hart, J.E.; Bailey, C.R.; Browning, M.H.; Casey, J.A.; Hanley, J.R.; Minson, C.T.; Ogletree, S.S.; Rigolon, A.; Laden, F.; et al. Racial, Ethnic, and Socioeconomic Disparities in Multiple Measures of Blue and Green Spaces in the United States. Environ. Health Perspect. 2023, 131, 17007. (In English) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlosberg, D.; Collins, L.B. From environmental to climate justice: Climate change and the discourse of environmental justice. WIREs Clim. Chang. 2014, 5, 359–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sultana, F. Critical climate justice. Geogr. J. 2022, 188, 118–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruin, A.; Boer, I.J.M.; Faber, N.; Jong, G.; Termeer, K.; De Olde, E. Easier said than defined? Conceptualising justice in food system transitions. Agric. Hum. Values 2023, 41, 345–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, A.; Armijos, M.T.; Coolsaet, B.; Dawson, N.; Edwards, G.A.S.; Few, R.; Gross-Camp, N.; Rodriguez, I.; Schroeder, H.; Tebboth, M.G.L.; et al. Environmental Justice and Transformations to Sustainability. Environ. Sci. Policy Sustain. Dev. 2020, 62, 19–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preston, C.; Carr, W. Recognitional Justice, Climate Engineering, and the Care Approach. Ethics Policy Environ. 2018, 21, 308–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cannon, C.E.B. Towards Convergence: How to Do Transdisciplinary Environmental Health Disparities Research. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 2303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anguelovski, I.; Connolly, J.J.T.; Cole, H.; Garcia-Lamarca, M.; Triguero-Mas, M.; Baró, F.; Martin, N.; Conesa, D.; Shokry, G.; del Pulgar, C.P.; et al. Green gentrification in European and North American cities. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 3816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolch, J.R.; Byrne, J.; Newell, J.P. Urban green space, public health, and environmental justice: The challenge of making cities ‘just green enough’. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2014, 125, 234–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donovan, G.H.; Prestemon, J.P.; Butry, D.T.; Kaminski, A.R.; Monleon, V.J. The politics of urban trees: Tree planting is associated with gentrification in Portland, Oregon. For. Policy Econ. 2021, 124, 102387. (In English) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmichael, C.E.; McDonough, M.H. Community Stories: Explaining Resistance to Street Tree-Planting Programs in Detroit, Michigan, USA. Soc. Nat. Resour. 2019, 32, 588–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riedman, E.; Roman, L.A.; Pearsall, H.; Maslin, M.; Ifill, T.; Dentice, D. Why don’t people plant trees? Uncovering barriers to participation in urban tree planting initiatives. Urban For. Urban Green. 2022, 73, 127597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattijssen, T.J.M.; Hennen, W.; Buijs, A.E.; De Dooij, P.; Van Lammeren, R.; Walet, L. Urban greening co-creation: Participatory spatial modelling to bridge data-driven and citizen-centred approaches. Urban For. Urban Green. 2024, 94, 128257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calderón-Argelich, A.; Anguelovski, I.; Connolly, J.J.T.; Baró, F. Greening plans as (re)presentation of the city: Toward an inclusive and gender-sensitive approach to urban greenspaces. Urban For. Urban Green. 2023, 86, 127984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chazan, M.; Baldwin, M. Granny Solidarity: Understanding Age and Generational Dynamics in Climate Justice Movements. Stud. Soc. Justice 2020, 13, 244–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ursin, M.; Lorgen, L.C.; Alvarado, I.A.O.; Smalsundmo, A.-L.; Nordgård, R.C.; Bern, M.R.; Bjørnevik, K. Promoting Intergenerational Justice Through Participatory Practices: Climate Workshops as an Arena for Young People’s Political Participation. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 727227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, L.K.; Svendsen, E.S.; Johnson, M.L.; Plitt, S. Not by trees alone: Centering community in urban forestry. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2022, 224, 104445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McArdle, R. Intersectional climate urbanism: Towards the inclusion of marginalised voices. Geoforum 2021, 126, 302–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malin, S.A.; Ryder, S.S. Developing deeply intersectional environmental justice scholarship. Environ. Sociol. 2018, 4, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amorim-Maia, A.T.; Anguelovski, I.; Chu, E.; Connolly, J. Intersectional climate justice: A conceptual pathway for bridging adaptation planning, transformative action, and social equity. Urban Clim. 2022, 41, 101053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derickson, K.; Walker, R.; Hamann, M.; Anderson, P.; Adegun, O.B.; Castillo-Castillo, A.; Guerry, A.; Keeler, B.; Llewellyn, L.; Matheney, A.; et al. The intersection of justice and urban greening: Future directions and opportunities for research and practice. Urban For. Urban Green. 2024, 95, 128279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bamford, N. Accessing embodied knowledge of place: A method. J. Urban. Int. Res. Placemaking Urban Sustain. 2024, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- California, U.O.S. Experiential Knowledge. Available online: https://sites.usc.edu/community-engaged-sustainability-research/which-model/experiential-knowledge (accessed on 28 May 2025).

- Keenan, O.J.; Green, A.R.; Young, A.R.; Katz, D.S.; Li, Q.; Xi, W.; Miller, D.L.; Williams, C.; Maxwell, E.N.; McMillan, G.L.; et al. Linking Urban Greening and Community Engagement with Heat-Related Health Outcomes: A Scoping Review of the Literature. Arboric. Urban For. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Service, U.S.A.F. Announcing Urban and Community Forestry Funding. Available online: https://www.fs.usda.gov/inside-fs/leadership/announcing-urban-and-community-forestry-funding (accessed on 12 March 2025).

- Harris, F.; Lyon, F. Transdisciplinary Environmental Research: A Review of Approaches to Knowledge Co-Production. Nexus Network Think Piece Series, Paper 002. 2014. Available online: https://www.research.herts.ac.uk/ws/portalfiles/portal/12138376/Harris_and_Lyon_Nexus_thinkpiece_002.pdf (accessed on 25 May 2025).

- NYC Department of Health and Mental Hygeine Bureau of Environmental Surveillance and Policy. Interactive Heat Vulnerability Index. Available online: https://a816-dohbesp.nyc.gov/IndicatorPublic/data-features/hvi/ (accessed on 15 May 2025).

- Nesbitt, L.; Meitner, M.J.; Sheppard, S.R.J.; Girling, C. The dimensions of urban green equity: A framework for analysis. Urban For. Urban Green. 2018, 34, 240–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matte, T.; Lane, K.; Tipaldo, J.F.; Barnes, J.; Knowlton, K.; Torem, E.; Anand, G.; Yoon, L.; Marcotullio, P.; Balk, D.; et al. NPCC4: Climate change and New York City’s health risk. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2024, 1539, 185–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ubiqus. Transcription Services. Available online: https://www.ubiqus.io/company/transcription-services/ (accessed on 27 January 2025).

- MAXQDA. Interview Analysis with MAXQDA. Available online: https://www.maxqda.com/interview-transcription-analysis (accessed on 31 January 2025).

- Otter.ai. Transcribe All Conversations. Available online: https://otter.ai/transcription?msockid=14ca759ed8f4649227b160aed980658e (accessed on 27 January 2025).

- McKim, C. Meaningful Member-Checking: A Structured Approach to Member-Checking. Am. J. Qual. Res. 2023, 7, 41–52. [Google Scholar]

- de Diego-Cordero, R.; Martínez-Herrera, A.; Coheña-Jiménez, M.; Luchetti, G.; Pérez-Jiménez, J.M. Ecospirituality and Health: A Systematic Review. J. Relig. Health 2024, 63, 1285–1306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beard, S.; Freeman, K.; Velasco, M.L.; Boyd, W.; Chamberlain, T.; Latoni, A.; Lasko, D.; Lunn, R.M.; O’fallon, L.; Packenham, J.; et al. Racism as a public health issue in environmental health disparities and environmental justice: Working toward solutions. Environ. Health 2024, 23, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weston, B.H. The Theoretical Foundations of Intergenerational Ecological Justice: An Overview. Hum. Rights Q. 2012, 34, 251–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javaid, S.; Habeeb, R. Participatory Planning in Urban Green Spaces: A Step towards Environmental and Social Equity. In Proceedings of the 6th National Seminar on Architecture for Masses on the theme of “Environmental Remediation & Rejuvenation”, New Delhi, India, 22–23 February 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Hopkins, L.P.; January-Bevers, D.J.; Caton, E.K.; Campos, L.A. A simple tree planting framework to improve climate, air pollution, health, and urban heat in vulnerable locations using non-traditional partners. Plants People Planet 2022, 4, 243–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonneau, A. Indigenous Knowledge Systems Often Overlooked in Academia. IndigiNews. Available online: https://indiginews.com/okanagan/indigenous-knowledge-systems-overlooked-in-academia (accessed on 22 January 2025).

- Artelle, K.A.; Adams, M.S.; Bryan, H.M.; Darimont, C.T.; Housty, J.; Housty, W.G.; Moody, J.E.; Moody, M.F.; Neasloss, D.G.; Service, C.N.; et al. Decolonial Model of Environmental Management and Conservation: Insights from Indigenous-led Grizzly Bear Stewardship in the Great Bear Rainforest. Ethics Policy Environ. 2021, 24, 283–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svendsen, E.; Campbell, L.K.; Fisher, D.R.; Connolly, J.J.; Johnson, M.L.; Sonti, N.F.; Locke, D.H.; Westphal, L.M.; Fisher, C.L.; Grove, M.; et al. Stewardship Mapping and Assessment Project; U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Northern Research Station: Delaware County, PA, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moskell, C.; Allred, S.B. Integrating Human and Natural Systems in Community Psychology: An Ecological Model of Stewardship Behavior. Am. J. Community Psychol. 2013, 51, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Integrated Heat Health Information System [NIHHIS]. The National Heat Strategy 2024–2030. Available online: https://cpo.noaa.gov/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/National_Heat_Strategy-2024-2030.pdf (accessed on 25 May 2025).

- NYC Mayor’s Office of Climate; Environmental Justice. NYC Urban Forest Plan 2025. Available online: https://www.urbanforestplan.nyc/ (accessed on 15 May 2025).

| Interview Type | Description | Number of Participants | Number of Interviews | Location |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Co-Creation Interviews | Interviews that addressed how we can establish community co-creation and engagement throughout our research process. Questions for the Community Interviews were workshopped in these meetings as well | 6 | 6 | Community leaders in Harlem, New York City |

| Urban Forestry Interviews | Interviews that explore the abstract and practical considerations of tree planting and management related to cooling | 10 | 5 | Urban tree professionals in the contiguous United States (Chicago, IL, USA; Durham, NC, USA; Los Angeles, CA, USA; New York, NY, USA; Philadelphia, PA, USA) |

| Community Interviews | Interviews that explore community perceptions around trees and urban greening as a solution to heat | 5 | 5 | Community leaders in heat-vulnerable neighborhoods in New York City (Chinatown, Manhattan; Flatlands, Brooklyn; Harlem, Manhattan; South Bronx) |

| Theme | Description |

|---|---|

| Environmental justice and health equity are interlinked and at the heart of this research |

|

| Religious and spiritual communities are important touchpoints in urban greening research |

|

| Intergenerational engagement ensures intergenerational inclusion |

|

| Human–environment relationships vary by individual and community |

|

| Community building makes co-creation and knowledge sharing between communities and researchers possible |

|

| Theme | Similarities | Differences |

|---|---|---|

| Environmental justice and health equity are interlinked and at the heart of this research |

|

|

| Religious and spiritual communities are important touchpoints in urban greening research |

|

|

| Intergenerational engagement ensures intergenerational inclusion |

|

|

| Human–environment relationships vary by individual and community |

|

|

| Community building makes co-creation and knowledge sharing between communities and researchers possible |

|

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Keenan, O.J.; Green, A.R.; Young, A.R.; Young, S.R.; Katz, D.S.W.; Miller, D.L.; Xi, W.; Lo, F.; Ortiz, E.; McMillan, G.; et al. Exploring Community Co-Creation in Tree Planting and Heat-Related Health Interventions: A Qualitative Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2025, 22, 896. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22060896

Keenan OJ, Green AR, Young AR, Young SR, Katz DSW, Miller DL, Xi W, Lo F, Ortiz E, McMillan G, et al. Exploring Community Co-Creation in Tree Planting and Heat-Related Health Interventions: A Qualitative Study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2025; 22(6):896. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22060896

Chicago/Turabian StyleKeenan, Olivia J., Aalayna R. Green, Alexander R. Young, Sarah R. Young, Daniel S. W. Katz, David L. Miller, Wenna Xi, Fiona Lo, Evelyn Ortiz, Glenn McMillan, and et al. 2025. "Exploring Community Co-Creation in Tree Planting and Heat-Related Health Interventions: A Qualitative Study" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 22, no. 6: 896. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22060896

APA StyleKeenan, O. J., Green, A. R., Young, A. R., Young, S. R., Katz, D. S. W., Miller, D. L., Xi, W., Lo, F., Ortiz, E., McMillan, G., Archer, C. L., & Ghosh, A. K. (2025). Exploring Community Co-Creation in Tree Planting and Heat-Related Health Interventions: A Qualitative Study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 22(6), 896. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22060896