Workforce Career Development in Public Health, Health Education, and the Health Services: Insights from 30 Years of Cross-Disciplinary National and International Mentoring

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

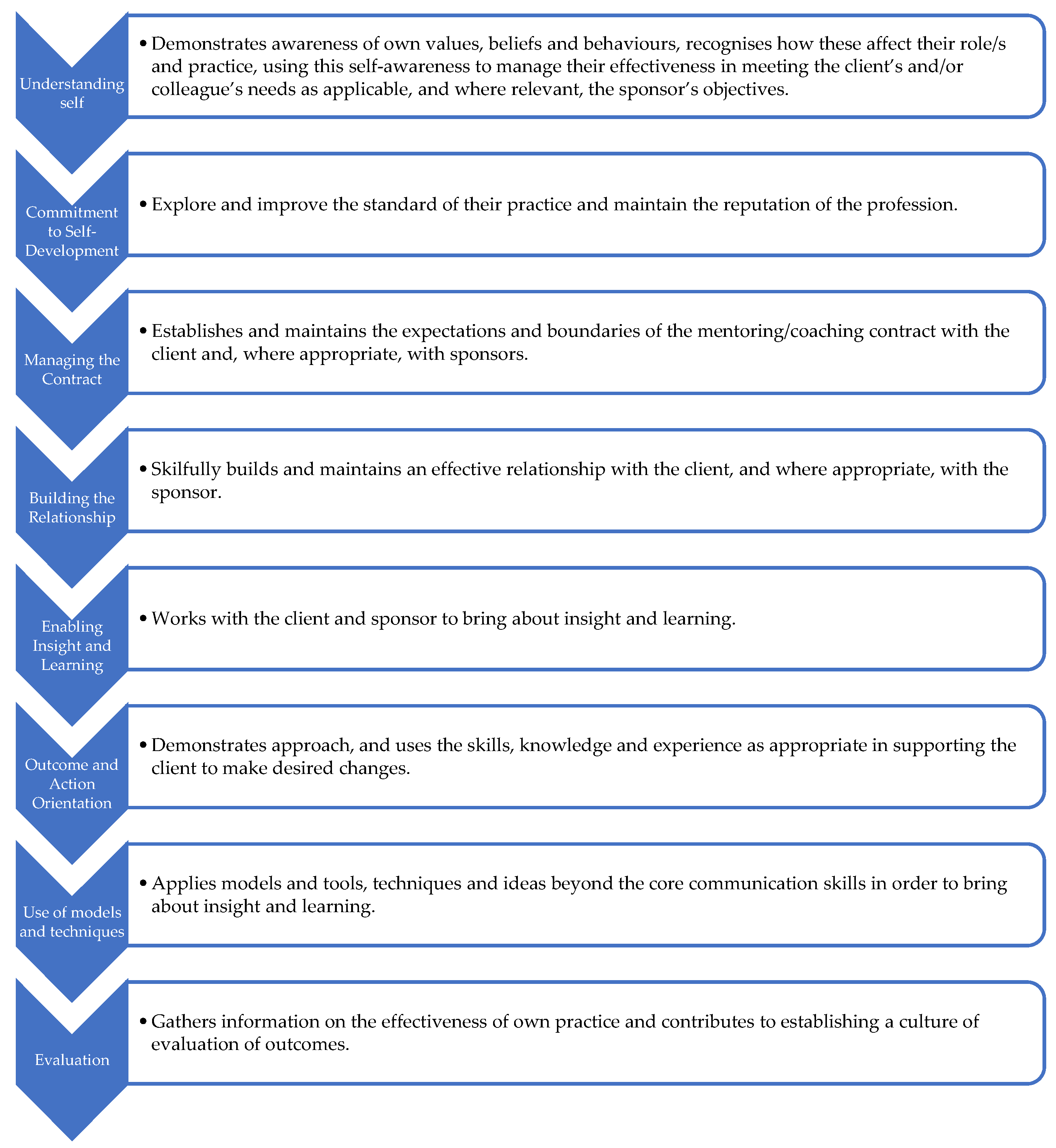

2.1. Professional Frameworks and Standards

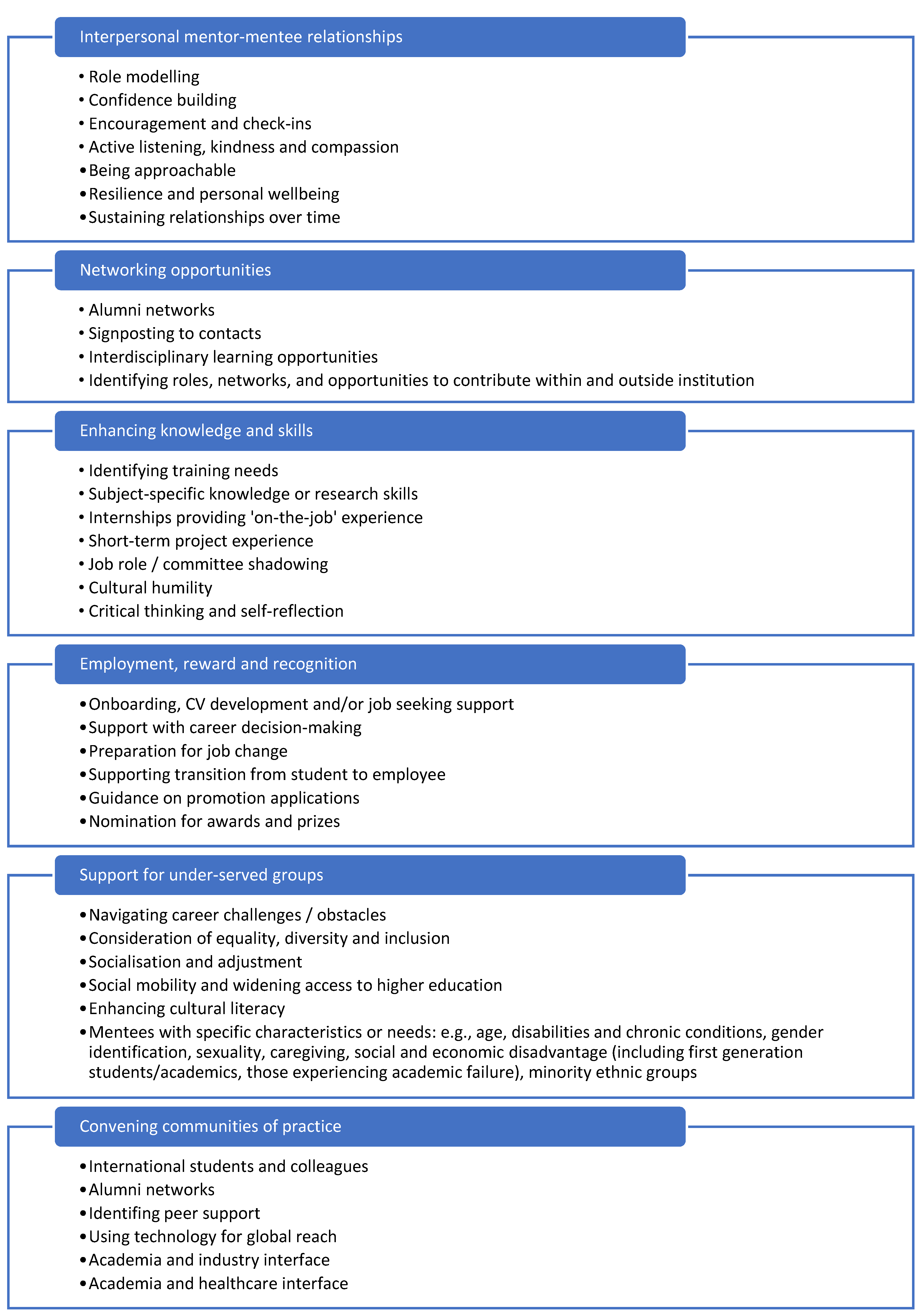

2.2. Mentoring Recipients and Contexts

2.2.1. One-to-One Mentoring Relationships

2.2.2. Establishing and Leading Structured Programmes

- (a)

- Cross-faculty structured mentoring programme

- (b)

- Cross-institutional interprofessional internship programme

- (c)

- Interprofessional learning programme: ‘WHIRL in Test@Work’

2.3. Evaluating Process and Outcomes

2.3.1. Reflection in Mentoring

- (1)

- To help the mentee to reflect on thoughts, processes, and experiences (e.g., to assist them in developing new knowledge, considering alternative perspectives, finding solutions, and ensuring mentoring is meeting their needs). This might involve working through a reflective model with a mentee. There are many models of reflection that could be used. One example that I have frequently used is the Gibbs Reflective Model [34], which offers a framework for examining experiences through six stages: description of the experience; feelings and thoughts about the experience; evaluation of the experience (good and bad); analysis to make sense of the situation; concluding with what you learned and what you could have done differently; and creating an action plan for how you would deal with similar situations in the future, or general changes you might find appropriate. Alternatively, reflective questions can simply be added to the end of each mentoring session, such as ‘What has been a success or challenge since we last spoke? What can we learn from that?’.

- (2)

- To reflect on one’s own practice as a mentor, recognising that we are imperfect and influenced by our own experiences, thoughts, biases, and way of doing things. Again, a reflective model could be used to consider one’s own role as a mentor, how effective one is at mentoring and role modelling, and how one’s positionality and privilege can contribute to, or influence, the relationship. I initially engaged in reflective practice on an individual level. This was largely due to a lack of obvious alternative approaches, particularly in the earlier years of my career, when fewer colleagues were engaging in, or reflecting on, mentoring practice. In more recent years, mentoring has become more prominent in career development discussions, and in some settings, best practice involves the establishment of communities of practice through which academic staff can discuss mentoring practices and access peer-to-peer support and/or supervision. I would now advocate a “supervised/supported” approach, since the supervision of mentoring practice not only supports the professional development of those acting as mentors, but can provide a quality assurance mechanism, helping to maintain high standards in mentoring by providing oversight and guidance.

2.3.2. Seeking 360° Feedback

2.3.3. Evaluation Surveys

3. Results

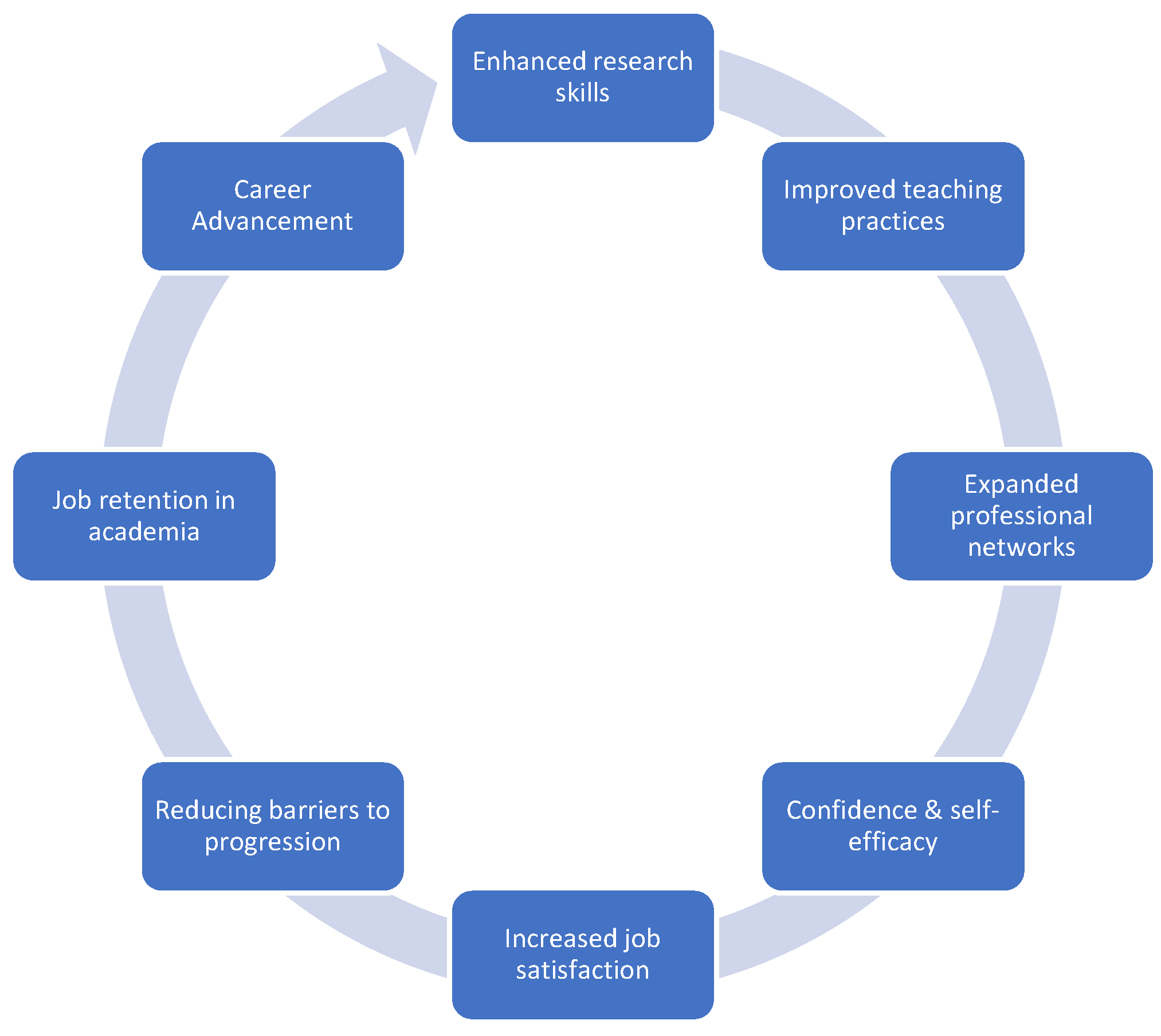

3.1. Learning from Diverse Mentoring Approaches

3.2. Formal Evaluation Results

4. Discussion

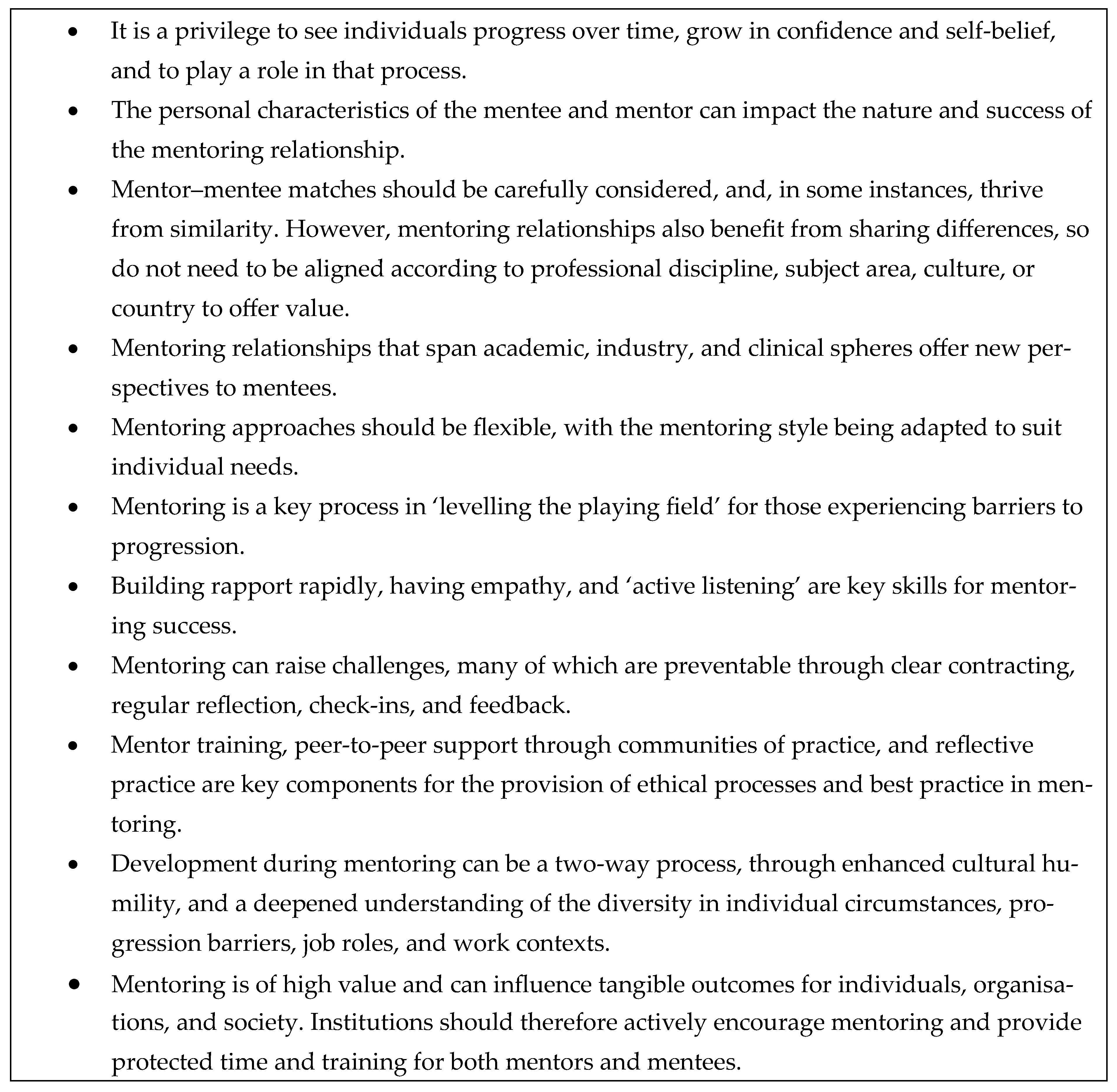

5. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| WHIRL | Workplace Health Interprofessional Learning |

| IRL | Interprofessional Learning |

| HIV | Human Immunodeficiency Virus |

| BMI | Body Mass Index |

References

- Crisp, G.; Cruz, I. Mentoring college students: A critical review of the literature between 1990 and 2007. Res. High. Educ. 2009, 50, 525–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EMCC Global. Professional Practice Framework for Mentors, Coaches, and Leaders Specific to Role and Context. June 2024. Available online: https://emccdrive.emccglobal.org/api/file/download/5uLuRItx5eyXPtvpjH4u5hm32IQQOtng8AY9m6JA (accessed on 26 January 2025).

- Nuis, W.; Segers, M.; Beausaert, S. Conceptualizing mentoring in higher education: A systematic literature review. Educ. Res. Rev. 2023, 41, 100565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox, M.D. Long-term patterns in a mentoring program for junior faculty: Recommendations for practice. Improv. Acad. 1997, 16, 225–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- DeCastro, R.; Griffith, K.A.; Ubel, P.A.; Stewart, A.; Jagsi, R. Mentoring and the career satisfaction of male and female academic medical faculty. Acad. Med. J. Assoc. Am. Med. Coll. 2014, 89, 301–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feldman, M.D.; Arean, P.A.; Marshall, S.J.; Lovett, M.; O’Sullivan, P. Does mentoring matter: Results from a survey of faculty mentees at a large health sciences university. Med. Educ. Online 2010, 15, 5063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garman, K.A.; Wingard, D.L.; Reznik, V. Development of junior faculty’s self-efficacy: Outcomes of a national center of leadership in academic medicine. Acad. Med. 2001, 76, S74–S76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morzinski, J.A.; Fisher, J.C. A nationwide study of the influence of faculty development programs on colleague relationships. Acad. Med. 2002, 77, 402–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gratrix, L.; Black, S.; Mason, R.; Parkhouse, T.; Hogue, T.; Ortega, M.; Kane, R. Supporting health and social care practitioners to transition to academia: A systematic review. Nurse Educ. Today 2025, 146, 106517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brightman, H.J. Mentoring faculty to improve teaching and student learning. Issues Account. Educ. 2006, 21, 127–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartell, C.A. Cultivating High-Quality Teaching Through Induction and Mentoring; Corwin Press: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Luke, D.A.; Baumann, A.A.; Carothers, B.J.; Landsverk, J.; Proctor, E.K. Forging a link between mentoring and collaboration: A new training model for implementation science. Implement. Sci. 2016, 11, 137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palepu, A.; Friedman, R.H.; Barnett, R.C.; Carr, P.L.; Ash, A.S.; Szalacha, L.; Moskowitz, M.A. Junior faculty members’ mentoring relationships and their professional development in U.S. medical schools. Acad. Med. 1998, 73, 318–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Risner, L.E.; Morin, X.K.; Erenrich, E.S.; Clifford, P.S.; Franke, J.; Hurley, I.; Schwartz, N.B. Leveraging a collaborative consortium model of mentee/mentor training to foster career progression of underrepresented postdoctoral researchers and promote institutional diversity and inclusion. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0238518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sambunjak, D.; Straus, S.E.; Marusic, A. A systematic review of qualitative research on the meaning and characteristics of mentoring in academic medicine. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2009, 25, 72–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ogden, K.; Thomas, M. Higher Education Spending. IFS Report R299, February 2024. Institute for Fiscal Studies. Available online: https://ifs.org.uk/sites/default/files/2024-02/Scottish-Budget-2024-Higher-Education-Spending-IFS-Report-R299.pdf (accessed on 28 January 2025).

- Office for Students. Financial Sustainability of Higher Education Providers in England: November 2024 Update. Available online: https://www.officeforstudents.org.uk/media/nn2fnrkx/financial-sustainability-november-2024.pdf (accessed on 28 January 2025).

- Brown, J.; Kurzweil, M. Instructional Quality, Student Outcomes, and Institutional Finances. American Council on Education. 2018. Available online: https://www.acenet.edu/Documents/Instructional-Quality-Student-Outcomes-and-Institutional-Finances.pdf (accessed on 27 January 2025).

- Knippelmeyer, S.A.; Torraco, R.J. Mentoring as a Developmental Tool for Higher Education. Available online: https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED504765.pdf (accessed on 20 February 2025).

- Tillman, L.C. Achieving Racial Equity in Higher Education: The Case for Mentoring Faculty of Color. Teach. Coll. Rec. Voice Scholarsh. Educ. 2018, 120, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, N. Encouraging Disabled Leaders in Higher Education: Recognising Hidden Talents. Leadership Foundation for Higher Education. 2017. Available online: https://openresearch.lsbu.ac.uk/download/f42d907f8b3ede580d56bd372faffc4d39e6c3e6c1f7201de41eff39c66ef761/707151/Encouraging-Disabled-Leaders-in-Higher-Education.pdf (accessed on 28 January 2025).

- Straus, S.E.; Johnson, M.O.; Marquez, C.; Feldman, M.D. Characteristics of successful and failed mentoring relationships: A qualitative study across two academic health centers. Acad. Med. 2013, 88, 82–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarabipour, S.; Niemi, N.M.; Burgess, S.J.; Smith, C.T.; Bisson Filho, A.W.; Ibrahim, A.; Clark, K. The faculty-to-faculty mentorship experience: A survey on challenges and recommendations for improvements. R. Soc. 2023, 290, 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lancer, N.; Clutterbuck, D.; Megginson, D. Techniques for Coaching and Mentoring, 2nd ed.; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CMI. Mentoring in Practice. Checklist 083. Chartered Management Institute. Corby, Northants, UK. Available online: https://www.managers.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2016/11/CHK-083-Mentoring-in-practice.pdf (accessed on 24 January 2025).

- CIPD. Coaching and Mentoring. Factsheet, 12 August 2024. Available online: https://www.cipd.org/uk/knowledge/factsheets/coaching-mentoring-factsheet/#what-are-coaching-and-mentoring (accessed on 24 January 2025).

- Blake, H.; Somerset, S.; Whittingham, K.; Middleton, M.; Yildirim, M.; Evans, C. WHIRL Study: Workplace Health Interprofessional Learning in the Construction Industry. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 6815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, W.; Somerset, S.; Evans, C.; Whittingham, K.; Middleton, M.; Blake, H. Test@work: Evaluation of workplace HIV testing for construction workers using the RE-AIM framework. BMC Public Health 2021, 21, 1737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Somerset, S.; Evans, C.; Blake, H. Accessing Voluntary HIV Testing in the Construction Industry: A Qualitative Analysis of Employee Interviews from the Test@Work Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 4184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Somerset, S.; Jones, W.; Evans, C.; Cirelli, C.; Mbang, D.; Blake, H. Opt-in HIV testing in construction workplaces: An exploration of its suitability, using the socioecological framework. BMC Public Health 2022, 22, 1409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

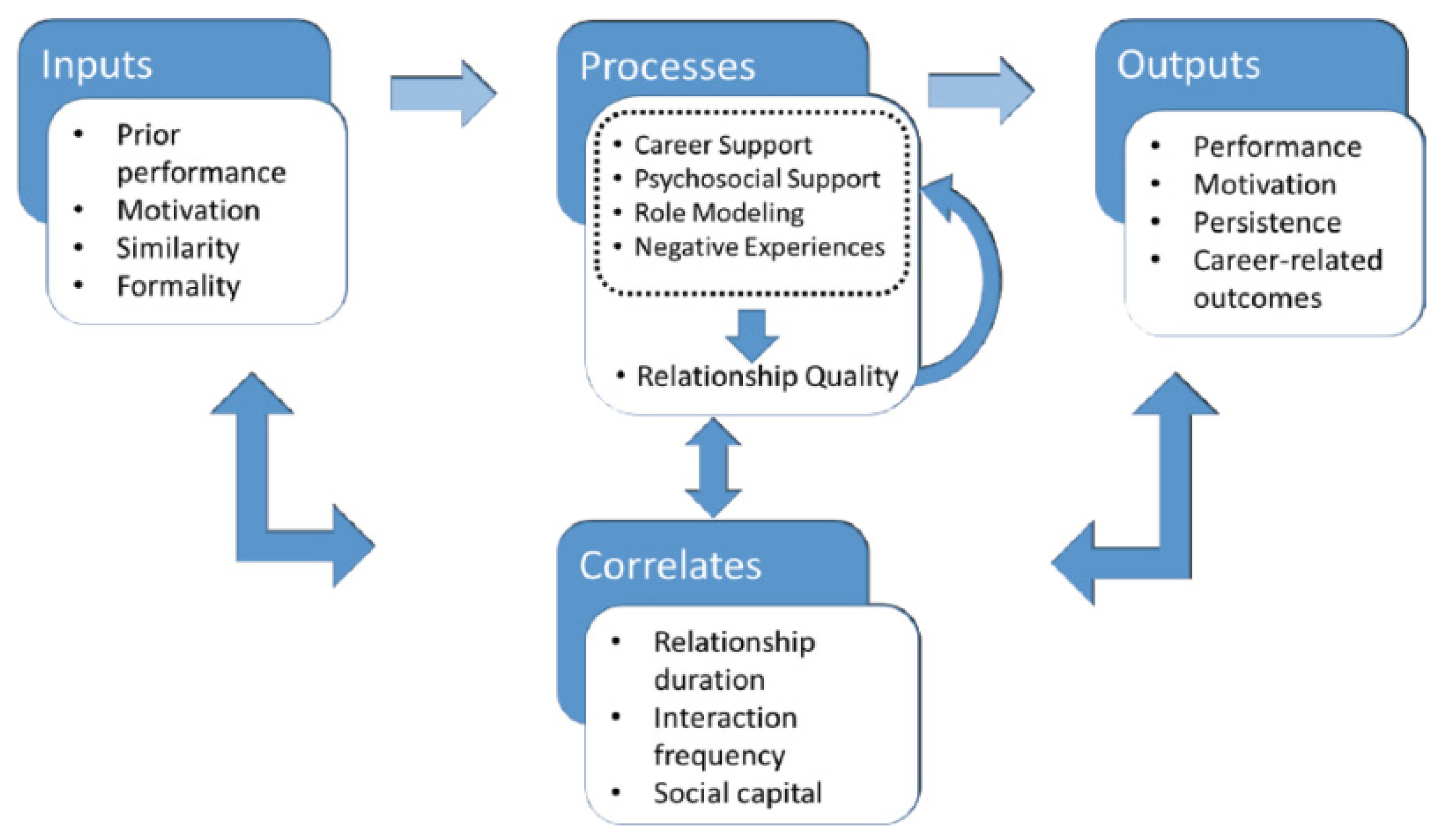

- Eby, L.T.; Allen, T.D.; Hoffman, B.J.; Baranik, L.E.; Sauer, J.B.; Baldwin, S.; Morrison, M.A.; Kinkade, K.M.; Maher, C.P.; Curtis, S.; et al. An interdisciplinary meta-analysis of the potential antecedents, correlates, and consequences of protégé perceptions of mentoring. Psychol. Bull. 2013, 139, 441–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahlberg, M.L.; Byars-Winston, A. (Eds.) Assessment and Evaluation: What Can Be Measured in Mentorship, and How? In The Science of Effective Mentorship in S.T.E.M.M; National Academies Press (US): Washington, DC, USA, 2019. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK552763/ (accessed on 28 January 2025).

- Lockwood, P.; Kunda, Z. Superstars and me: Predicting the impact of role models on the self. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1997, 73, 91–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibbs, G. Learning by Doing: A Guide to Teaching and Learning Methods; Further Education Unit, Oxford Brookes University: Oxford, UK, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Day, D.V.; Fleenor, J.W.; Atwater, L.E.; Sturm, R.E.; McKee, R.A. Advances in leader and leadership development: A review of 25 years of research and theory. Leadersh. Q. 2014, 25, 63–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellison, L.J.; Steelman, L.A.; Young, S.F.; Riordan, B.G. Setting the stage: Feedback environment improves outcomes for a 360-degree-feedback leader-development program. Consult. Psychol. J. 2022, 74, 363–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hénard, F.; Roseveare, D. Fostering Quality Teaching in Higher Education: Policies and Practices. An IMHE Guide for Higher Education Institutions. Institutional Management in Higher Education (IMHE). September 2012. Available online: https://learningavenue.fr/assets/pdf/QT%20policies%20and%20practices.pdf (accessed on 20 February 2025).

- Kram, K. Phases of the mentor relationship. Acad. Manag. J. 1983, 26, 608–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, M. Developmental Network Questionnaire; Harvard Business Publishing. 2004. Available online: https://hbsp.harvard.edu/product/404105-PDF-ENG (accessed on 28 February 2025).

- Tigges, B.; Soller, B.; Myers, O.; Shore, X.; Mickel, N.; Dominguez, N.; Wiskur, B.; Helitzer, D.; Sood, A. Mentoring Network Questionnaire Support Scales Reliable and Valid with University Faculty. Chron. Mentor. Coach. 2023, 7, 459–465. [Google Scholar]

- Fothergill, L.J.; Al-Oraibi, A.; Houdmont, J.; Conway, J.; Evans, C.; Timmons, S.; Pearce, R.; Blake, H. Nationwide evaluation of the advanced clinical practitioner role in England: A cross-sectional survey. BMJ Open 2022, 12, e055475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, C.; Pearce, R.; Greaves, S.; Blake, H. Advanced Clinical Practitioners in Primary Care in the UK: A Qualitative Study of Workforce Transformation. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 4500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AdvanceHE. The Professional Standards Framework (PSF) 2023 and Principal Fellowship. Available online: https://www.advance-he.ac.uk/fellowship/principal-fellowship (accessed on 6 February 2025).

- Ayyala, M.S.; Skarupski, K.; Bodurtha, J.; González-Fernández, M.; Ishii, L.; Fivush, B.; Levine, R.B. Mentorship Is Not Enough: Exploring Sponsorship and Its Role in Career Advancement in Academic Medicine. Acad. Med. 2019, 94, 94–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kram, K. Mentoring at Work: Developmental Relationships in Organizational Life; Scott Foresman & Co.: Glenview, IL, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Tinto, V. Leaving College: Rethinking the Causes and Cures of Student Attrition; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Knowles, M.S.; Holton, E.F., III; Swanson, R.A. The Adult Learner: The Definitive Classic in Adult Education and Human Resource Development; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Baker, V.L.; Lattuca, L.R. Developmental networks and learning: Toward an interdisciplinary perspective on identity development during doctoral study. Stud. High. Educ. 2010, 35, 807–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Revans, R.W. What is Action Learning? J. Manag. Dev. 1982, 1, 64–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dirkx, J.M.; Espinoza, B.D.; Schlegel, S. “Critical Reflection and Imaginative Engagement: Towards an Integrated Theory of Transformative Learning,” Adult Education Research. Conference. 2018. Available online: https://newprairiepress.org/aerc/2018/papers/4 (accessed on 26 April 2025).

- Wenger, E. Communities of Practice: Learning, Meaning, and Identity; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levinson, D.J. A theory of life structure development in adulthood. In Higher Stages of Human Development: Perspectives on Adult Growth; Alexander, C.N., Langer, E.J., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1990; pp. 35–53. [Google Scholar]

- Gannon, B.; Roberts, J. Social capital: Exploring the theory and empirical divide. Empir. Econ. 2020, 58, 899–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Argyris, C.; Schon, D. Organizational Learning: A Theory of Action Perspective; Addison-Wesley: Reading, MA, USA, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, W.B. On Being a Mentor: A Guide for Higher Education Faculty, 2nd ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cummings, C.; Laing, K.; Law, J.; McLaughlin, J.; Papps, I.; Todd, L.; Woolner, P. Can Changing Aspirations and Attitudes Impact on Educational Attainment; Joseph Rowntree Foundation: York, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Abelev, M.S. Advancing out of poverty: Social class worldview and its relation to resilience. J. Adolesc. Res. 2009, 24, 114–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, A.; Hunter, K.; Spohrer, K.; Bruner, R.; Beasley, A. Mentoring into higher education: A useful addition to the landscape of widening access to higher education? Scott. Educ. Rev. 2014, 46, 18–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Myers-Briggs Company. Myers-Briggs Type Indicator® (MBTI®). Available online: https://www.themyersbriggs.com/en-US/Products-and-Services/Myers-Briggs (accessed on 6 February 2025).

- AdvanceHE. University of Nottingham Vice-Chancellor’s Mentoring Programme. Best Practice Case Studies. Published 15 February 2022. Available online: https://www.advance-he.ac.uk/knowledge-hub/vice-chancellors-mentoring-programme (accessed on 28 May 2024).

- National Careers Service. Benefits of a Mentor. Available online: https://nationalcareers.service.gov.uk/careers-advice/getting-the-most-out-of-mentoring/ (accessed on 28 May 2024).

- Greco, V.; Politi, K.; Eisenbarth, S.; Colón-Ramos, D.; Giraldez, A.J.; Bewersdorf, J.; Berg, D.N. A group approach to growing as a principal investigator. Curr. Biol. 2022, 32, R498–R504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Mentoring Type | Use Cases | Benefits |

|---|---|---|

| Micro-mentoring | Short-term or single session Focused on a topic, skill, or short-term project Shadowing opportunities Support with awards and recognition (e.g., reviewing promotion applications, supporting development of applications for achievement awards) Individual approach | Low time commitment Short-term/measurable objectives Enhances organisational understanding Improves academic performance Supports achievement and productivity |

| Inducting new staff | Onboarding Short-term Focused on job role profile, teams, and environment Individual approach | Low time commitment Short-term/measurable objectives Rapport building Socialisation and adjustment |

| Peer mentoring | Inclusion within a team Environment and team support, and specific skills or characteristics (e.g., disability) Individual approach | Relationship building Signposting Socialisation and adjustment |

| Career transition moments | Researcher to tenured academic Student to early career researcher Job exchange (e.g., new comparable research contract or clinical role; move from academia to industry or reverse) Individual or group approach | Low/medium time commitment Short-term/measurable objectives Eases transitions Preparation for challenging experiences Individual enablement |

| Career advancement mentoring | Professional development Individual approach | Individual enablement Succession planning Future-proofing Staff retention |

| Diversity mentoring | Inclusion (protected characteristics) Career development Leadership development Individual or group approach | Support for under-served individuals Improvement of diversity in leadership or specific job roles Reduction in unconscious bias Builds social capital and social mobility Enhances cultural humility Widens access to higher education Facilitates adjustment and achievement |

| Knowledge sharing mentoring | Upskilling Training Career development Individual or group approach | Building skills in specific areas, functions, or use of technology Engages senior/experienced staff in skill or knowledge sharing |

| Collaborative learning and support mentoring | Career development Upskilling Group approach | Rapport building Intraprofessional relationship building and support |

| Leadership development mentoring | Upskilling High-potential development Individual or group approach | Enhances leadership potential |

| Stage | Considerations |

|---|---|

| Planning | Establish programme purpose and goals Clear programme leadership, and senior leadership ‘buy-in’ Identify resources (e.g., training materials for mentor training, support staff) Establish clear guidelines, expectations, and organisational goals Focus on target groups (e.g., staffing groups, under-represented groups) Decide on the nature of mentoring (e.g., one-to-one mentoring relationships, peer mentoring, group mentoring, or reverse mentoring) Identify suitably experienced mentors Identify prospective mentees Consider how participants enrol Determine mentor/mentee matching process Decide on programme duration Establish feedback mechanisms Consider offering awards/rewards/benefits for participation Advertise the programme by highlighting key benefits and salient features |

| Initiation | Introduce programme organisers Deliver training to mentors and mentees Emphasise the three C’s of mentorship—communication, clarity, and commitment Perform careful matching of mentors with mentees (e.g., consider sociodemographic characteristics, education, experience, subject expertise, location) Establish clear communication channels Ensure expectations are realistic Dyads set up meetings Create plan for tracking progress |

| Mentoring | Identify areas for growth and development Flexibility with frequency of meetings and mode of communication Regular feedback Consider recommending formal training and professional development |

| Evaluation | Assess mentee progress through appropriate method (e.g., reflection, discussion, goal attainment) Collect mentor/programme feedback (e.g., reflection, discussion, evaluation survey, focus group) |

| Challenges | Actions |

|---|---|

| Mismatched expectations | Discuss expectations up front Consider providing written guidance Build shared understanding Suggest alternative pairing if relevant |

| Lack of communication of stressors by mentees | Reinforce confidentiality Build rapport and trust Provide multiple contact options Provide open feedback |

| Lack of goal setting by mentees | Discuss expectations up front Consider providing written guidance Assist with setting specific and measurable goals Focus on goals as meeting discussion points |

| Lack of planning by mentees | Discuss expectations up front Send reminders prior to meeting Emphasise individual accountability |

| Lack of mentor training | Undertake mentor training Seek diverse mentoring experiences |

| Balancing time and commitment | Provide multiple contact options Provide options for remote contacts Set clear limitations and boundaries Adhere to agreed contact frequency Adjust number of mentees if necessary |

| Overcoming resistance to change | Build mentee confidence Encourage mentee to set realistic goals Appreciate mentees’ personal and work situation and competing demands |

| Maintaining mentee engagement | Evaluate outcomes to support reflection Regularly assess mentoring needs Adapt mentoring style to suit the relationship Offer flexibility where possible Signpost to an alternative pairing if relevant |

| Dealing with mentee inexperience | Identify knowledge/skills gaps Provide opportunities to learn/develop skills (where appropriate and without abuse of power) Signpost to opportunities |

| Fostering mentee independence | Build mentee confidence Set clear limitations and boundaries Realistic goal setting Encourage mentee decision-making Enable mentoring closure |

| Unknown outcomes | Measure outcomes through the following: 360° feedback for mentor Informal evaluation: regular reflection/discussion Formal evaluation: gather metrics |

| Career Support Scale (n = 103) | Min–Max * | Mean | S.D. |

|---|---|---|---|

| Provides you with opportunities that stretch you professionally | 5–7 | 6.80 | 0.492 |

| Creates opportunities for visibility for you in your career | 4–7 | 6.76 | 0.551 |

| Opens doors for you professionally | 5–7 | 6.82 | 0.437 |

| Acts as a sponsor for you | 2–7 | 6.84 | 0.622 |

| Acts as a buffer for you from situations that could threaten your career achievement | 1–7 | 6.48 | 1.092 |

| Total (33.66/35) | |||

| Psychosocial Support Scale (n = 103) | Min–Max * | Mean | S.D. |

| Cares and shares in ways that extend beyond the requirements of work | 4–7 | 6.89 | 0.441 |

| Counsels you on non-work-related issues | 4–7 | 6.72 | 0.663 |

| Offers you support, respect, and encouragement | 7–7 | 7.00 | 0 |

| Is a friend of yours | 3–7 | 6.25 | 0.957 |

| Confirms and affirms your identify and sense of self | 5–7 | 6.95 | 0.257 |

| Total (33.81/35) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Blake, H. Workforce Career Development in Public Health, Health Education, and the Health Services: Insights from 30 Years of Cross-Disciplinary National and International Mentoring. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2025, 22, 729. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22050729

Blake H. Workforce Career Development in Public Health, Health Education, and the Health Services: Insights from 30 Years of Cross-Disciplinary National and International Mentoring. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2025; 22(5):729. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22050729

Chicago/Turabian StyleBlake, Holly. 2025. "Workforce Career Development in Public Health, Health Education, and the Health Services: Insights from 30 Years of Cross-Disciplinary National and International Mentoring" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 22, no. 5: 729. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22050729

APA StyleBlake, H. (2025). Workforce Career Development in Public Health, Health Education, and the Health Services: Insights from 30 Years of Cross-Disciplinary National and International Mentoring. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 22(5), 729. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22050729