Health Disparities at the Intersection of Racism, Social Determinants of Health, and Downstream Biological Pathways

Abstract

1. Introduction

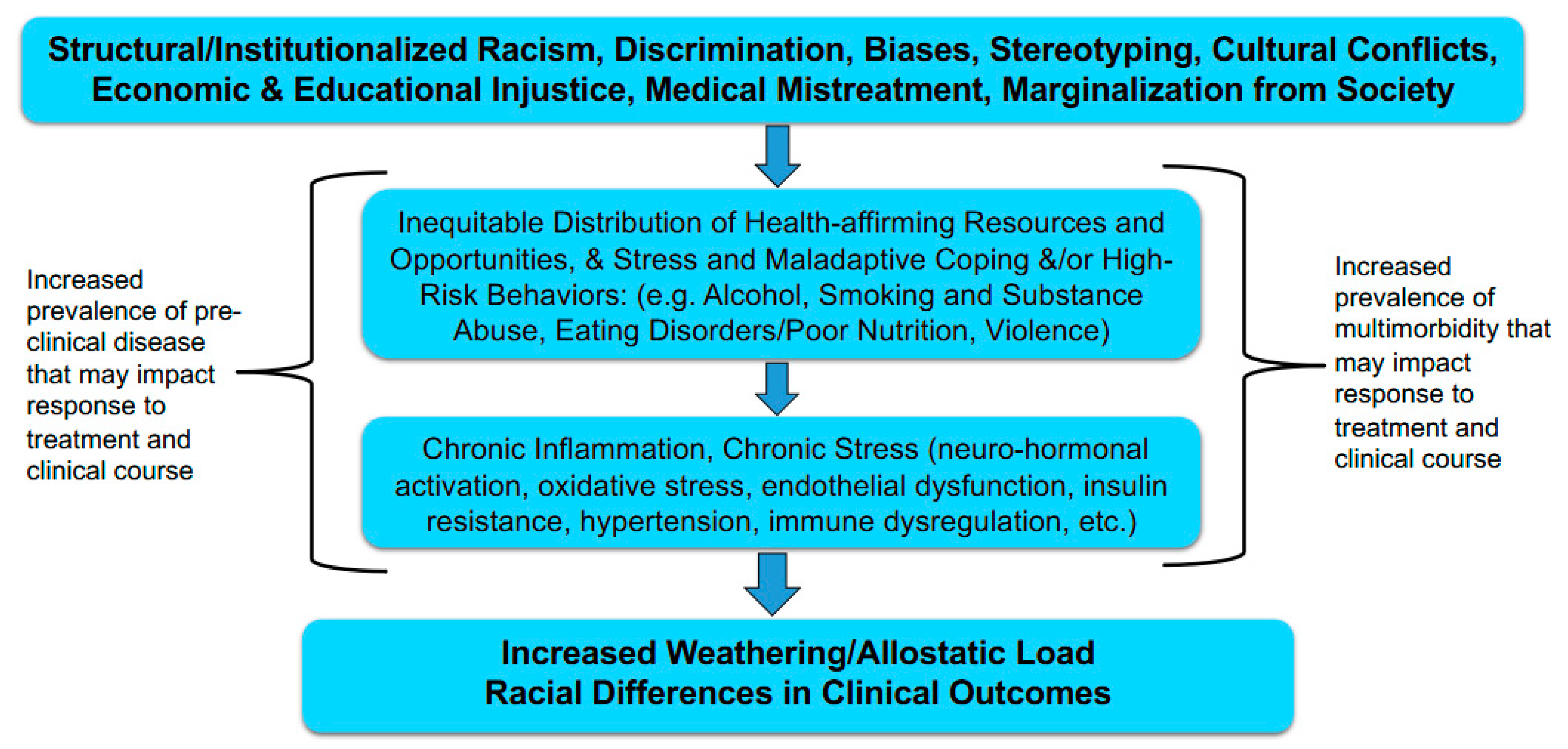

2. The Biology of Stress in Racial/Ethnic Disparities

3. Biologic Pathways

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Breslow, L. A quantitative approach to the World Health Organization definition of health: Physical, mental and social well-being. Int. J. Epidemiol. 1972, 1, 347–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bohm, D. Wholeness and the Implicate Order; Routledge: London, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Heart, B.; DeBruyn, L.M. The American Indian holocaust: Healing historical unresolved grief. Am. Indian Alsk. Nativ. Ment. Health Res. 1998, 8, 56–78. [Google Scholar]

- Smedley, B.D. Expanding the frame of understanding health disparities: From a focus on health systems to social and economic systems. Health Educ. Behav. 2006, 33, 538–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Contrada, R.J.; Ashmore, R.D.; Gary, M.L.; Coups, E.; Egeth, J.D.; Sewell, A.; Ewell, K.; Goyal, T.M.; Chasse, V. Ethnicity-Related Sources of Stress and Their Effects on Well-Being. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 2000, 9, 136–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brondolo, E.; Gallo, L.C.; Myers, H.F. Race, racism and health: Disparities, mechanisms, and interventions. J. Behav. Med. 2009, 32, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LaVeist, T.A. Minority Populations and Health: An Introduction to Health Disparities in the United States; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2005; Volume 4. [Google Scholar]

- Chou, R.S.; Feagin, J.R. Myth of the Model Minority: Asian Americans Facing Racism; Routledge: London, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Griffith, D.M.; Mason, M.; Yonas, M.; Eng, E.; Jeffries, V.; Plihcik, S.; Parks, B. Dismantling institutional racism: Theory and action. Am. J. Community Psychol. 2007, 39, 381–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braveman, P.; Gottlieb, L. The Social Determinants of Health: It’s Time to Consider the Causes of the Causes. Public Health Rep. 2014, 129 (Suppl. S2), 19–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Rethinking Race and Ethnicity in Biomedical Research; The National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, C.P. Confronting Institutionalized Racism. Phylon 2002, 50, 7–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geronimus, A.T. The weathering hypothesis and the health of African-American women and infants: Evidence and speculations. Ethn. Dis. 1992, 2, 207–221. [Google Scholar]

- Geronimus, A.T.; Hicken, M.; Keene, D.; Bound, J. “Weathering” and age patterns of allostatic load scores among blacks and whites in the United States. Am. J. Public Health 2006, 96, 826–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McEwen, B.S. Protective and damaging effects of stress mediators. N. Engl. J. Med. 1998, 338, 171–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thames, A.D.; Irwin, M.R.; Breen, E.C.; Cole, S.W. Experienced discrimination and racial differences in leukocyte gene expression. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2019, 106, 277–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heckler, M. Report of the Secretary’s Task Force on Black & Minority Health; US Department of Health and Human Services: Washington, DC, USA, 1985.

- Smedley, B.D.; Stith, A.Y.; Nelson, A.R. Unequal Treatment: Confronting Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care (with CD); National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Peek, M.E.; Gottlieb, L.M.; Doubeni, C.A.; Viswanathan, M.; Cartier, Y.; Aceves, B.; Fichtenberg, C.; Cené, C.W. Advancing health equity through social care interventions. Health Serv. Res. 2023, 58 (Suppl. S3), 318–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailey, Z.D.; Krieger, N.; Agénor, M.; Graves, J.; Linos, N.; Bassett, M.T. Structural racism and health inequities in the USA: Evidence and interventions. Lancet 2017, 389, 1453–1463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill-Briggs, F.; Fitzpatrick, S.L. Overview of Social Determinants of Health in the Development of Diabetes. Diabetes Care 2023, 46, 1590–1598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paradies, Y.; Ben, J.; Denson, N.; Elias, A.; Priest, N.; Pieterse, A.; Gupta, A.; Kelaher, M.; Gee, G. Racism as a Determinant of Health: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0138511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priest, N.; Paradies, Y.; Trenerry, B.; Truong, M.; Karlsen, S.; Kelly, Y. A systematic review of studies examining the relationship between reported racism and health and wellbeing for children and young people. Soc. Sci. Med. 2013, 95, 115–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paradies, Y.; Truong, M.; Priest, N. A systematic review of the extent and measurement of healthcare provider racism. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2014, 29, 364–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, W.L.; Bell, J.M. Maneuvers of whiteness: ‘Diversity’as a mechanism of retrenchment in the affirmative action discourse. Crit. Sociol. 2011, 37, 597–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, S.; Janicki-Deverts, D.; Miller, G.E. Psychological stress and disease. JAMA J. Am. Med. Assoc. 2007, 298, 1685–1687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chae, D.H.; Wang, Y.; Martz, C.D.; Slopen, N.; Yip, T.; Adler, N.E.; Fuller-Rowell, T.E.; Lin, J.; Matthews, K.A.; Brody, G.H.; et al. Racial discrimination and telomere shortening among African Americans: The Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults (CARDIA) Study. Health Psychol. Off. J. Div. Health Psychol. Am. Psychol. Assoc. 2020, 39, 209–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Connell, M.A.; Hayes, J.D. The Keap1/Nrf2 pathway in health and disease: From the bench to the clinic. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2015, 43, 687–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dirven, B.C.J.; Homberg, J.R.; Kozicz, T.; Henckens, M. Epigenetic programming of the neuroendocrine stress response by adult life stress. J. Mol. Endocrinol. 2017, 59, R11–R31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thorpe, R.J., Jr.; Kelley-Moore, J.A. Race, Ethnicity, and Health, 2nd ed.; LaVeist, T.A., Isaac, L.A., Eds.; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2013; pp. 355–374. [Google Scholar]

- Hill, C.V.; Perez-Stable, E.J.; Anderson, N.A.; Bernard, M.A. The National Institute on Aging Health Disparities Research Framework. Ethn. Dis. 2015, 25, 245–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvidrez, J.; Castille, D.; Laude-Sharp, M.; Rosario, A.; Tabor, D. The National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities Research Framework. Am. J. Public Health 2019, 109, S16–S20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, C.P. Levels of racism: A theoretic framework and a gardener’s tale. Am. J. Public Health 2000, 90, 1212–1215. [Google Scholar]

- Ford, C.L.; Airhihenbuwa, C.O. Critical Race Theory, race equity, and public health: Toward antiracism praxis. Am. J. Public Health 2010, 100 (Suppl. S1), S30–S35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crimmins, E.M.; Seeman, T.E. Integrating biology into the study of health disparities. Popul. Dev. Rev. 2004, 30, 89–107. [Google Scholar]

- Myers, H.F. Ethnicity- and socio-economic status-related stresses in context: An integrative review and conceptual model. J. Behav. Med. 2009, 32, 9–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powe, N.R. Let’s get serious about racial and ethnic disparities. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2008, 19, 1271–1275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norris, K.; Nissenson, A.R. Race, gender, and socioeconomic disparities in CKD in the United States. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. JASN 2008, 19, 1261–1270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bruce, M.A.; Griffith, D.M.; Thorpe, R.J., Jr. Stress and the kidney. Adv. Chronic Kidney Dis. 2015, 22, 46–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boyd, R.W.; Lindo, E.G.; Weeks, L.D.; McLemore, M.R. On Racism: A New Standard for Publishing on Racial Health Inequities; Health Affairs Blog: Washington, DC, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Egede, L.E.; Walker, R.J. Structural Racism, Social Risk Factors, and COVID-19—A Dangerous Convergence for Black Americans. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 383, e77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cogburn, C.D. Culture, Race, and Health: Implications for Racial Inequities and Population Health. Milbank Q. 2019, 97, 736–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thorpe, J.R.; Norris, K.C.; Beech, B.M.; Bruce, M.A. Racism Across the Life Course. In Is It Race or Racism? State of the Evidence & Tools for the Public Health Professional, 1st ed.; APHA: Washington, DC, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Ellis, K.R.; Griffith, D.M.; Allen, J.O.; Thorpe, R.J., Jr.; Bruce, M.A. “If you do nothing about stress, the next thing you know, you’re shattered”: Perspectives on African American men’s stress, coping and health from African American men and key women in their lives. Soc. Sci. Med. 2015, 139, 107–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brockie, T.N.; Heinzelmann, M.; Gill, J. A Framework to Examine the Role of Epigenetics in Health Disparities among Native Americans. Nurs. Res. Pract. 2013, 2013, 410395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powell, W.; Richmond, J.; Mohottige, D.; Yen, I.; Joslyn, A.; Corbie-Smith, G. Medical Mistrust, Racism, and Delays in Preventive Health Screening Among African-American Men. Behav. Med. 2019, 45, 102–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, M.D.; Michaels, E.K.; Reeves, A.N.; Okoye, U.; Price, M.M.; Hasson, R.E.; Chae, D.H.; Allen, A.M. Differential associations between everyday versus institution-specific racial discrimination, self-reported health, and allostatic load among black women: Implications for clinical assessment and epidemiologic studies. Ann. Epidemiol. 2019, 35, 20–28.e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, D.R.; Wyatt, R. Racial Bias in Health Care and Health: Challenges and Opportunities. JAMA J. Am. Med. Assoc. 2015, 314, 555–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, D.R.; Mohammed, S.A. Racism and Health I: Pathways and Scientific Evidence. Am. Behav. Sci. 2013, 57, 1152–1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Djuric, Z.; Bird, C.E.; Furumoto-Dawson, A.; Rauscher, G.H.; Iv, M.T.R.; Stowe, R.P.; Tucker, K.L.; Masi, C.M. Biomarkers of Psychological Stress in Health Disparities Research. Open Biomark. J. 2008, 1, 7–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Richardson, L.J.; Goodwin, A.N.; Hummer, R.A. Social status differences in allostatic load among young adults in the United States. SSM-Popul. Health 2021, 15, 100771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seeman, T.E.; Singer, B.H.; Rowe, J.W.; Horwitz, R.I.; McEwen, B.S. Price of adaptation--allostatic load and its health consequences. MacArthur studies of successful aging. Arch. Intern. Med. 1997, 157, 2259–2268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Forde, A.T.; Crookes, D.M.; Suglia, S.F.; Demmer, R.T. The weathering hypothesis as an explanation for racial disparities in health: A systematic review. Ann. Epidemiol. 2019, 33, 1–18.e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McEwen, B.S.; Stellar, E. Stress and the individual. Mechanisms leading to disease. Arch. Intern. Med. 1993, 153, 2093–2101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rozanski, A.; Blumenthal, J.A.; Kaplan, J. Impact of psychological factors on the pathogenesis of cardiovascular disease and implications for therapy. Circulation 1999, 99, 2192–2217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halliwell, B.; Gutteridge, J.M.; Cross, C.E. Free radicals, antioxidants, and human disease: Where are we now? J. Lab. Clin. Med. 1992, 119, 598–620. [Google Scholar]

- Saha, S.; Buttari, B.; Panieri, E.; Profumo, E.; Saso, L. An Overview of Nrf2 Signaling Pathway and Its Role in Inflammation. Molecules 2020, 25, 5474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Vries, H.E.; Witte, M.; Hondius, D.; Rozemuller, A.J.M.; Drukarch, B.; Hoozemans, J.; van Horssen, J. Nrf2-induced antioxidant protection: A promising target to counteract ROS-mediated damage in neurodegenerative disease? Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2008, 45, 1375–1383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, A.M.; Thomas, M.D.; Michaels, E.K.; Reeves, A.N.; Okoye, U.; Price, M.M.; Hasson, R.E.; Syme, S.L.; Chae, D.H. Racial discrimination, educational attainment, and biological dysregulation among midlife African American women. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2019, 99, 225–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saban, K.L.; Mathews, H.L.; Bryant, F.B.; Tell, D.; Joyce, C.; DeVon, H.A.; Janusek, L.W. Perceived discrimination is associated with the inflammatory response to acute laboratory stress in women at risk for cardiovascular disease. Brain Behav. Immun. 2018, 73, 625–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tu, W.; Wang, H.; Li, S.; Liu, Q.; Sha, H. The Anti-Inflammatory and Anti-Oxidant Mechanisms of the Keap1/Nrf2/ARE Signaling Pathway in Chronic Diseases. Aging Dis. 2019, 10, 637–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, J.; Ma, J.Z.; Zeng, Q.; Cechova, S.; Gantz, A.; Nievergelt, C.; O’Connor, D.; Lipkowitz, M.; Le, T.H. Loss of GSTM1, a NRF2 target, is associated with accelerated progression of hypertensive kidney disease in the African American Study of Kidney Disease (AASK). Am. J. Physiol. Physiol. 2013, 304, F348–F355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Willcox, B.J.; Tranah, G.J.; Chen, R.; Morris, B.J.; Masaki, K.H.; He, Q.; Willcox, D.C.; Allsopp, R.C.; Moisyadi, S.; Poon, L.W.; et al. The FoxO3 gene and cause-specific mortality. Aging Cell 2016, 15, 617–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.Y.; Xia, W.; Hu, M.C. Ionizing radiation activates expression of FOXO3a, Fas ligand, and Bim, and induces cell apoptosis. Int. J. Oncol. 2006, 29, 643–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillespie, S.L.; Anderson, C.M. Racial discrimination and leukocyte glucocorticoid sensitivity: Implications for birth timing. Soc. Sci. Med. 2018, 216, 114–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, M.C.; Ji, J.A.; Jiang, Z.Y.; You, Q.D. The Keap1-Nrf2-ARE Pathway As a Potential Preventive and Therapeutic Target: An Update. Med. Res. Rev. 2016, 36, 924–963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, S.; Hou, D.X. Multiple regulations of Keap1/Nrf2 system by dietary phytochemicals. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2016, 60, 1731–1755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rich, T.; Chrisinger, B.W.; Kaimal, R.; Winter, S.J.; Hedlin, H.; Min, Y.; Zhao, X.; Zhu, S.; You, S.L.; Sun, C.A.; et al. Contemplative Practices Behavior Is Positively Associated with Well-Being in Three Global Multi-Regional Stanford WELL for Life Cohorts. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 13485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simons, R.L.; Lei, M.-K.; Klopack, E.; Beach, S.R.; Gibbons, F.X.; Philibert, R.A. The effects of social adversity, discrimination, and health risk behaviors on the accelerated aging of African Americans: Further support for the weathering hypothesis. Soc. Sci. Med. 2021, 282, 113169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Adverse Social Determinants of Health | Sample Mechanisms of Adverse Health Impact | Potential Interventions |

|---|---|---|

| Low Income |

|

|

| Limited or Absent Health Insurance and/or Access to Care |

|

|

| Low Level of Educational Attainment |

|

|

| Limited Health Literacy |

|

|

| Poor Nutrition |

|

|

| Limited Green Space Exposure |

|

|

| Distrust of Medical Institutions |

|

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Thorpe, R.J., Jr.; Bruce, M.A.; Wilder, T.; Jones, H.P.; Thomas Tobin, C.; Norris, K.C. Health Disparities at the Intersection of Racism, Social Determinants of Health, and Downstream Biological Pathways. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2025, 22, 703. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22050703

Thorpe RJ Jr., Bruce MA, Wilder T, Jones HP, Thomas Tobin C, Norris KC. Health Disparities at the Intersection of Racism, Social Determinants of Health, and Downstream Biological Pathways. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2025; 22(5):703. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22050703

Chicago/Turabian StyleThorpe, Roland J., Jr., Marino A. Bruce, Tanganyika Wilder, Harlan P. Jones, Courtney Thomas Tobin, and Keith C. Norris. 2025. "Health Disparities at the Intersection of Racism, Social Determinants of Health, and Downstream Biological Pathways" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 22, no. 5: 703. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22050703

APA StyleThorpe, R. J., Jr., Bruce, M. A., Wilder, T., Jones, H. P., Thomas Tobin, C., & Norris, K. C. (2025). Health Disparities at the Intersection of Racism, Social Determinants of Health, and Downstream Biological Pathways. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 22(5), 703. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22050703